Published online Jan 14, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i2.733

Peer-review started: August 19, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: October 23, 2021

Accepted: December 7, 2021

Article in press: December 7, 2021

Published online: January 14, 2022

Processing time: 145 Days and 4.7 Hours

Severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding (SLGIB) is a rare complication of Crohn's disease (CD). The treatment of these patients is a clinical challenge. Monoclonal anti-TNFα antibody (IFX) can induce relatively fast mucosal healing. It has been reported for the treatment of SLGIB, but there are few reports on accelerated IFX induction in CD patients with SLGIB.

A 16-year-old boy with a history of recurrent oral ulcers for nearly 1 year presented to the Gastroenterology Department of our hospital complaining of recurrent periumbilical pain for more than 1 mo and having bloody stool 4 times within 2 wk. Colonoscopy showed multiple areas of inflammation of the colon and a sigmoid colon ulcer with active bleeding. Hemostasis was immediately performed under endoscopy. The physical examination of the patient showed scattered small ulcers in the lower lip of the mouth and small cracks in the perianal area. Combined with his medical history, physical examination, laboratory examinations with high C-reactive protein (CRP), platelet count (PLT), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and fecal calprotectin levels, imaging examinations and pathology, a diagnosis of CD was taken into consideration. According to the pediatric CD activity index 47.5, methylprednisolone (40 mg QD) was given intravenously. The abdominal pain disappeared, and CRP, PLT, and ESR levels decreased significantly after the treatment. Unfortunately, he had a large amount of bloody stool again after 1 wk of methylprednisolone treatment, and his hemoglobin level decreased quickly. Although infliximab (IFX) (5 mg/kg) was given as a combination therapy regimen, he still had bloody stool with his hemoglobin level decreasing from 112 g/L to 80 g/L in a short time, so-called SLGIB. With informed consent, accelerated IFX (5 mg/kg) induction was given 7 days after initial presentation. The bleeding then stopped. Eight weeks after the treatment, repeat colonoscopy showed mucosal healing; thus far, no recurrent bleeding has occurred, and the patient is symptom-free.

This case highlights the importance of accelerated IFX induction in SLGIB secondary to CD, especially after steroid hormone treatment.

Core Tip: Severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding (SLGIB) is a rare complication of Crohn's disease (CD) that is potentially life-threatening. The treatment of these patients is a clinical challenge. Monoclonal anti-TNFα antibody infliximab (IFX) can induce relatively fast mucosal healing. It has been reported for the treatment of SLGIB, but there are few reports on accelerated IFX induction in CD patients with SLGIB. We present a patient with CD complicated with SLGIB. The bleeding was finally controlled, and colonoscopy showed mucosal healing after accelerated IFX induction.

- Citation: Zeng J, Shen F, Fan JG, Ge WS. Accelerated Infliximab Induction for Severe Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in a Young Patient with Crohn’s Disease: A Case Report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(2): 733-740

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i2/733.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i2.733

Crohn's disease (CD) is a subtype of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1]. Severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding (SLGIB) is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication of CD. The incidence of acute LGIB secondary to CD in China ranges from 0.6% to 6%[2]. The definition of SLGIB in CD has changed over the years. In 1976, Homan et al[3] defined it as profuse rectal bleeding that required blood transfusions to maintain normal vital signs. In a recent case series, the definition was again modified to a drop in hemoglobin (Hb) of 2 g/dL below the baseline +/- hemodynamic instability or an abrupt fall in Hb to less than 9[4,5]. Monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibody (IFX) can induce relatively fast mucosal healing. It has been reported for the treatment of SLGIB, but there are few reports on the accelerated IFX induction in CD patients with SLGIB. We present a patient with CD complicated with SLGIB. The bleeding was controlled, and colonoscopy showed mucosal healing after accelerated IFX induction.

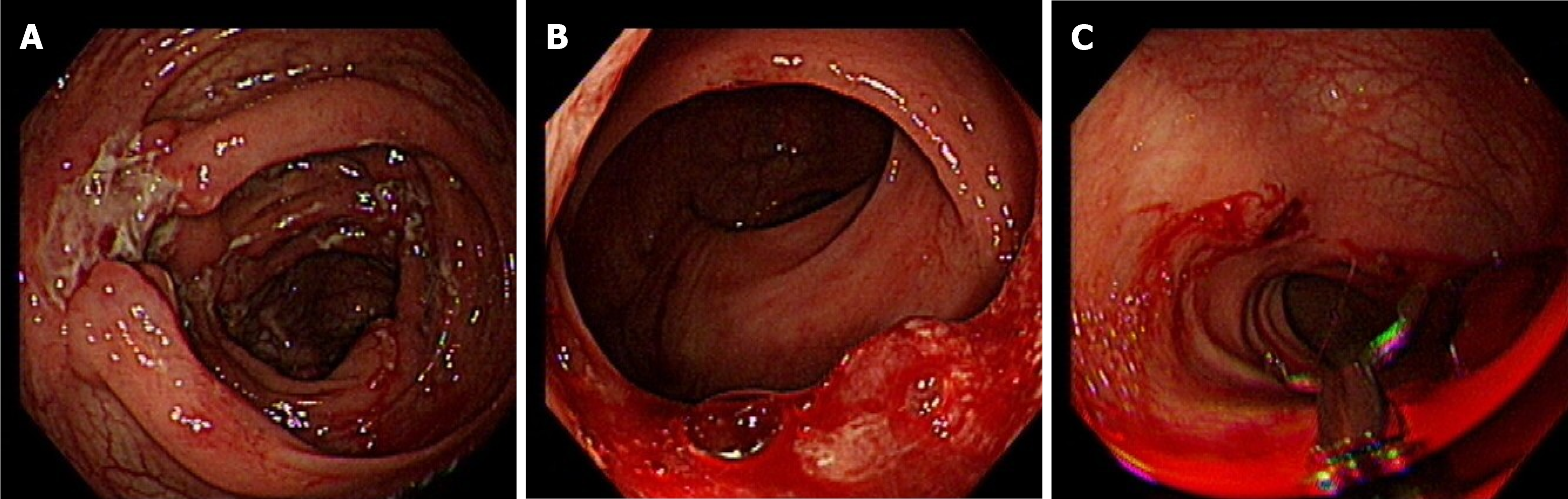

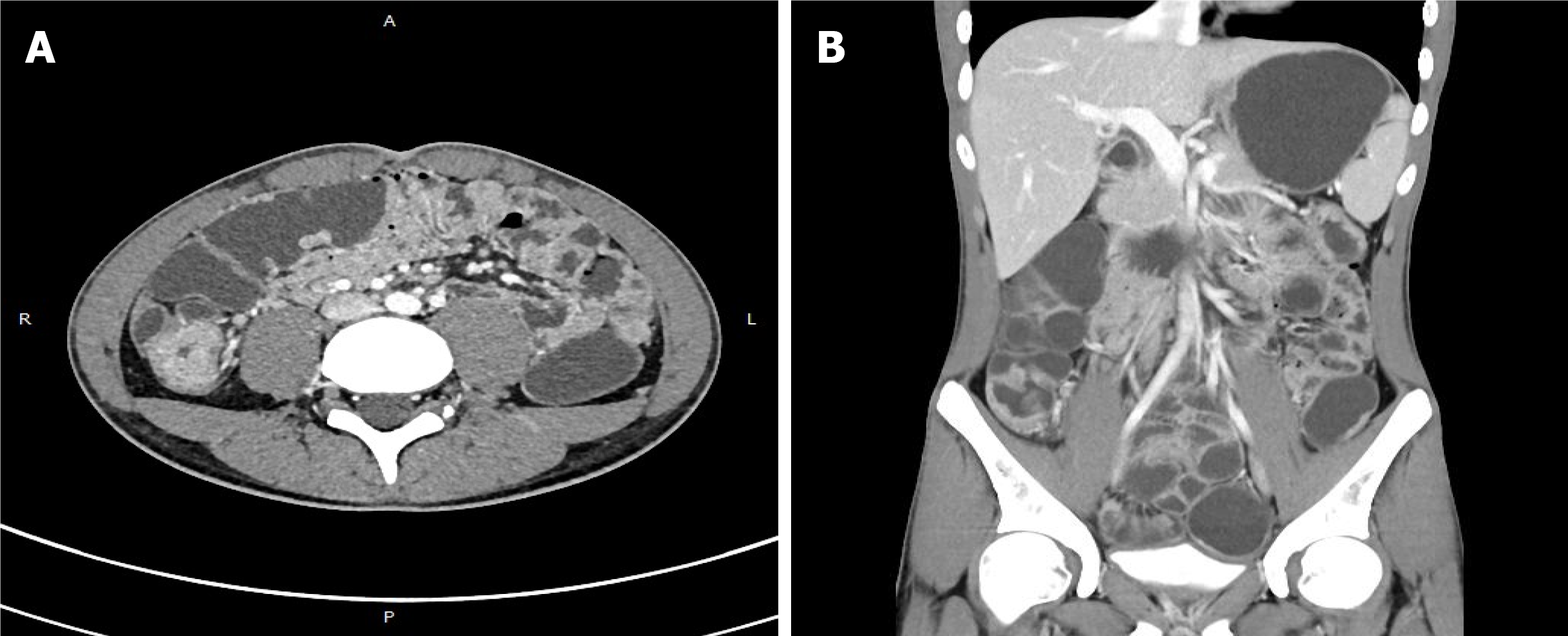

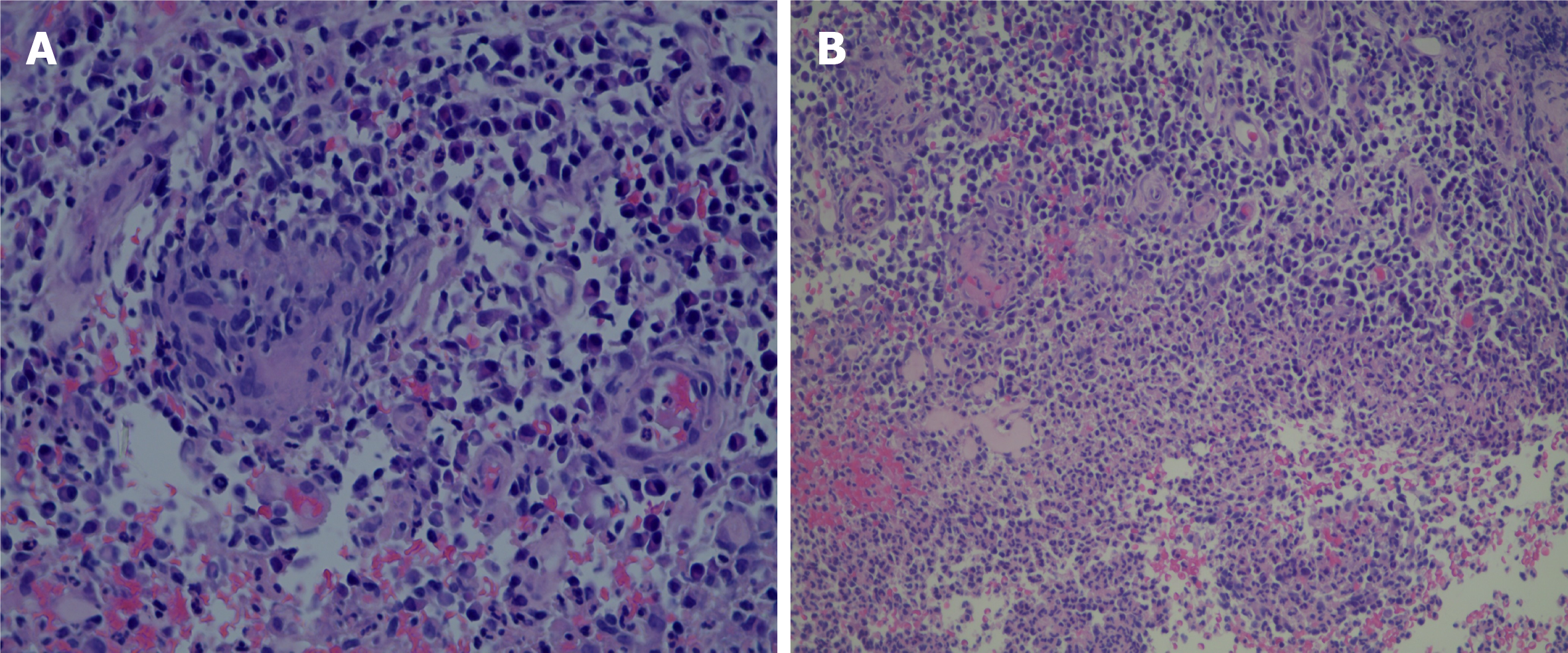

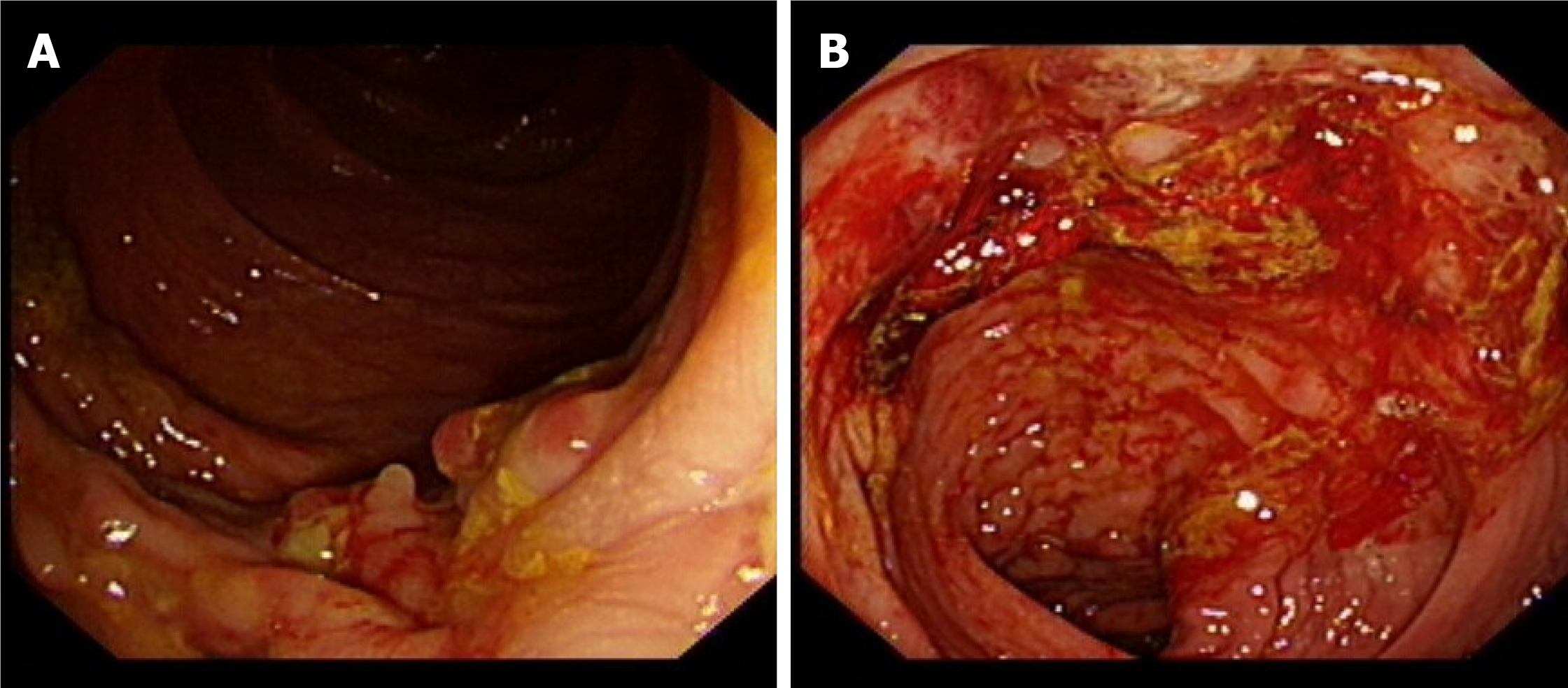

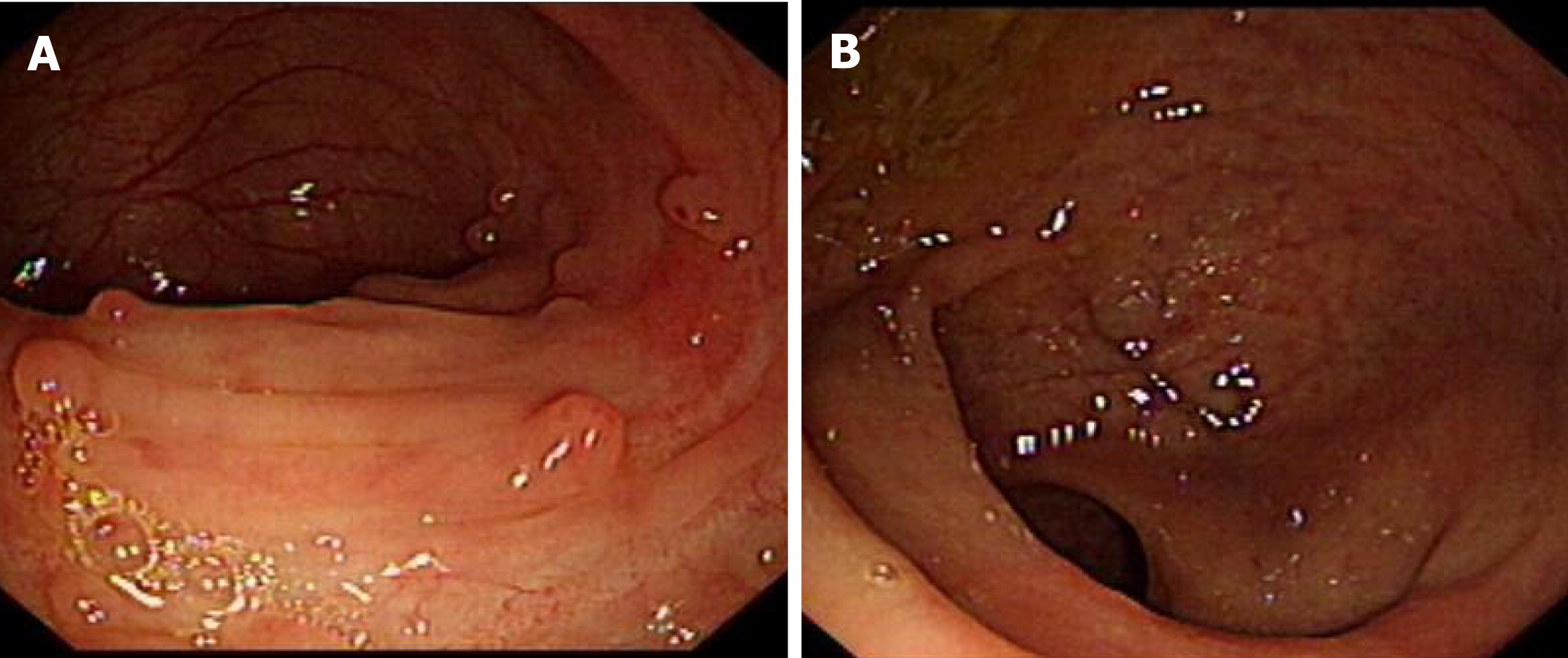

Initial colonoscopy on 15 July 2020 revealed multiple areas of inflammation of the colon (Figure 1A) and a sigmoid colon ulcer with bleeding (Figure 1B). Hemostasis was achieved under endoscopy (Figure 1C). Enhanced computerized tomography of the small intestine noted thickened walls of the small intestine and colon on 18 July 2020 (Figures 2A, 2B). Pathology revealed acute on chronic inflammation with granulation tissue, compatible with CD. In addition, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) immunohistochemical staining and acid-fast staining were negative (Figures 3A, 3B). Colonoscopy on 25 July 2020 showed multiple ulcers with hemorrhage (Figures 4A, 4B). After accelerated IFX induction therapy, colonoscopy showed mucosal healing in 8 wk (Figures 5A, 5B).

Blood analysis revealed leukocytosis (16.67 × 109/L), with predominant neutrophils (82%), mild anemia (hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL), and platelets that were increased slightly to 348.0 × 109/L. Serum C-reactive protein content was increased at 123 mg/L (normal range < 5 mg/L), and the red blood cell sedimentation rate was 82 mm/h. The fecal calprotectin was increased at 1703.43 µg/g, and both anti-intestinal goblet cell and anti-pancreatic exocrine gland antibodies were positive. Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time, electrocardiogram and urinalysis were all normal. CMV immunoglobulin (Ig) M, IgG, CMV DNA, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-VCA IgM, EBV DNA, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody (Ab), amoeba antibodies, Clostridium difficile toxin, Salmonella, Shigella cultures, and Campylobacter were all negative. Positive stool pus and occult blood were noted.

Physical examination on admission showed a body temperature of 36.0 °C, heart rate of 91 bpm, arterial blood pressure of 113/66 mmHg, respiratory rate of 18/min, and oxygen saturation in room air of 100%. Small ulcers could be seen in the mouth and scattered on the lower lip, and small cracks could be seen around the anus.

The patient had a noncontributory previous personal and family history.

He had a history of recurrent oral ulcers for nearly 1 year without special treatment.

The patient complained of recurrent periumbilical pain for more than 1 mo with no obvious causes. Appendicitis was suspected in the local hospital, and he received anti-inflammatory treatment. However, the periumbilical pain did not improve, and he suffered bloody stool 4 times in the 2 wk before admission. He also mentioned weight loss of 10 kg within 1 year.

A 16-year-old boy presented to the Department of Gastroenterology in our hospital complaining of recurrent periumbilical pain without obvious predisposing causes for more than 1 mo and bloody stool 4 times within 2 wk.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was SLGIB secondary to CD (Montreal A1L2B1p). The pediatric CD activity index (PCDAI) was 47.5 points.

The patient, following the diagnosis of severe CD, was immediately started on methylprednisolone 40 mg QD intravenously combined with nasal feeding enteral nutrition support treatment. IFX (5 mg/kg) was given when uncontrolled bleeding occurred 1 wk after treatment with methylprednisolone on 25 July 2020. The second IFX (5 mg/kg) treatment was given on 1 August 2020 for uncontrolled SLGIB. After 8 wk of treatment, colonoscopy showed mucosal healing.

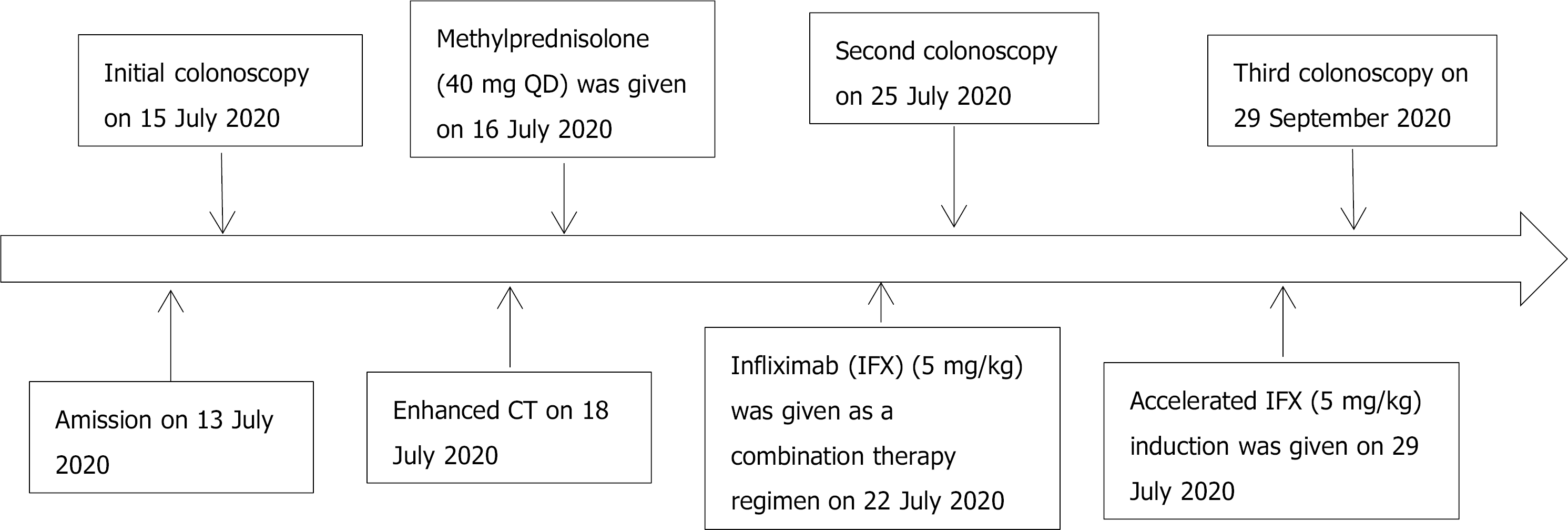

On 29 September 2020, follow-up colonoscopy showed that the mucosa had healed without any ulcers (Figures 5A, 5B). After 8 wk of IFX treatment, the PCDAI was 5 points. Thus far, the bleeding has not recurred. His body weight increased 10 kg, and his height increased 2 cm as of 1 August 2021. The timeline information of this patient was shown in Figure 6.

CD is a subtype of IBD, which is characterized by transmural inflammation of the entire intestinal wall, which can lead to various serious complications, including intestinal obstruction, intra-abdominal abscess and intestinal fistula[1]. Among them, SLGIB is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication of CD. Cirocco et al[6] reported that the incidence of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) in 631 CD patients was 0.6%, while Kim et al[4] reported that the incidence of LGIB in 1731 CD patients was 4%. In general, the reported incidence of acute LGIB secondary to CD in China ranges from 0.6% to 6% [2,4,7]. Li et al[1] also found that patients with a past medical history of bleeding, lesions involving the left colon, and the use of azathioprine for less than 1 year were all risk factors for acute LGIB in CD patients. Male sex was also found to be a risk factor[8]. Mazor et al[9] and Severs et al[10] even reported that only male sex was independently associated with complex complications, including stenosis, penetrating lesions and perianal lesions, and a high risk of needing surgical intervention. In our case, the patient was a 16-year-old boy. Therefore, further research may be needed to confirm the influence of sex on acute LGIB in CD patients in the future.

The treatment of CD has developed continuously in recent years, including the use of mesalazine, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants. For SLGIB in CD patients, surgical treatment was the most commonly chosen treatment strategy in the past; it has a lower rebleeding risk than conservative drug therapy [1,11]. However, it was also very difficult to identify the bleeding sites accurately in SLGIB in CD, and the risk of postoperative intestinal obstruction, anastomotic leakage, fistula, and short bowel syndrome was very high[12]. In our case, the patient was very young. Considering the large range of lesions and possible postoperative complications, surgical intervention was not considered. In some SLGIB in CD, local injection of adrenaline or thrombin under endoscopy could effectively stop the bleeding[13]. However, it is difficult to stop the bleeding under endoscopy if there are multiple bleeding sites with both ileum and colon involvement. In this case, we performed endoscopic homeostasis twice but were unable to stop the bleeding completely. Belaiche et al[13] found that corticosteroids could be used to treat LGIB in CD patients. However, some studies[4,14,15] reported that the effect of corticosteroids on the treatment of LGIB in CD was not exact and that those receiving corticosteroids were more likely to rebleed. The patient in our case was treated with standard corticosteroid therapy at first, but he still had bloody stool after 1 wk of treatment.

With the advent of IFX, an increasing number of reports have described IFX for the treatment of CD with acute LGIB with a significant effect. IFX is an anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody that can counteract the TNF-α-mediated intestinal inflammatory response, quickly reduce inflammation of the intestinal wall, promote ulcer healing, and effectively prevent and control the occurrence of bleeding[11]. As early as 2003, Papi et al[16] reported 2 cases of CD patients with recurrent LGIB that achieved mucosal healing after the application of IFX (5 mg/kg), and bleeding did not reoccur. Aniwan et al[11] also reported 7 cases of LGIB secondary to CD. All patients stopped bleeding after 1–2 rounds of treatment with IFX (5 mg/kg). Therefore, IFX may be an ideal choice for LGIB in CD.

Nevertheless, there were a large number of patients who did not have a good response to IFX, which might be related to a high drug clearance rate, excessive stool loss, reduced drug exposure, and poor drug response[17,18]. For these patients, some studies suggested shortening the IFX infusion time from the recommended 2 h to 1 h to improve the therapeutic effect[19]. On the other hand, accelerated IFX induction is increasingly used in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis (UC) patients who do not have a good response to the first IFX induction. In the guidelines, the "accelerated IFX induction (AD IFX)" is when the frequency of administration of IFX during the induction period exceeds the frequency of administration recommended in the latest product monograph[20]. AD IFX can better and more quickly control the disease[21]. It can reduce the occurrence of early colectomy[22]. The decision to use shorter dosing intervals rather than dose escalations is based on the pharmacokinetics of IFX. Therefore, AD IFX has been increasingly used in clinical practice. Since 2014, AD IFX induction in accelerated severe UC patients has been used in clinical practice in the Republic of Ireland, specifically for patients with more severe disease or poor initial response to standard treatment of IFX[21]. However, AD IFX is rarely reported to be used in CD patients. In our case, according to the PCDAI, methylprednisolone (40 mg QD) was given intravenously. Unfortunately, he had a large amount of bloody stool again after 1 wk of methylprednisolone treatment, with a rapidly decreasing hemoglobin level. Although IFX (5 mg/kg) was given as a combination therapy regimen, he still had bloody stool, with the hemoglobin level decreasing sharply in a short time as in SLGIB. With informed consent, AD IFX (5 mg/kg) was given 7 days after the first treatment. The bleeding then stopped. Eight weeks after the treatment, colonoscopy showed mucosal healing, the patient was symptom-free, and thus far, no recurrent bleeding has occurred. However, it is worth noting that although Peyrin-Biroulet et al[23] found that IFX did not increase the risk of death, tumor or serious infection in CD patients through meta-analysis, a clinical study[24] found that the incidence of upper respiratory tract and urinary tract infections in the IFX group and the control group were 36% and 26%, respectively. There was also a case report of a fatal pulmonary disease caused by IFX[25]. However, in our patient, we have not observed adverse side effects in the follow-up to date.

SLGIB is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication of CD. It is suggested that AD IFX may be an effective treatment option if the bleeding is severe and cannot be well controlled in these patients. However, in view of the limited medical evidence at present, it is necessary to carefully identify the applicable populations systematically and actively summarize the applicability in such populations. It is necessary to conduct larger-scale, multicenter, prospective studies to further decide whether AD IFX is advantageous.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Di Nardo G S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | Li G, Ren J, Wang G, Wu Q, Gu G, Ren H, Liu S, Hong Z, Li R, Li Y, Guo K, Wu X, Li J. Prevalence and risk factors of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee S, Ye BD, Park SH, Lee KJ, Kim AY, Lee JS, Kim HJ, Yang SK. Diagnostic Value of Computed Tomography in Crohn's Disease Patients Presenting with Acute Severe Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Korean J Radiol. 2018;19:1089-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Homan WP, Tang CK, Thorbjarnarson B. Acute massive hemorrhage from intestinal Crohn disease. Report of seven cases and review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1976;111:901-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim KJ, Han BJ, Yang SK, Na SY, Park SK, Boo SJ, Park SH, Yang DH, Park JH, Jeong KW, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Kim JH. Risk factors and outcome of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:723-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pardi DS, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ, Alexander GL, Balm RK, Gostout CJ. Acute major gastrointestinal hemorrhage in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:153-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cirocco WC, Reilly JC, Rusin LC. Life-threatening hemorrhage and exsanguination from Crohn's disease. Report of four cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:85-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kostka R, Lukás M. Massive, life-threatening bleeding in Crohn's disease. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105:168-174. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Yoon J, Kim DS, Kim YJ, Lee JW, Hong SW, Hwang HW, Hwang SW, Park SH, Yang DH, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK. Risk factors and prognostic value of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:2353-2365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mazor Y, Maza I, Kaufman E, Ben-Horin S, Karban A, Chowers Y, Eliakim R. Prediction of disease complication occurrence in Crohn's disease using phenotype and genotype parameters at diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Severs M, Spekhorst LM, Mangen MJ, Dijkstra G, Löwenberg M, Hoentjen F, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Pierik M, Ponsioen CY, Bouma G, van der Woude JC, van der Valk ME, Romberg-Camps MJL, Clemens CHM, van de Meeberg P, Mahmmod N, Jansen J, Jharap B, Weersma RK, Oldenburg B, Festen EAM, Fidder HH. Sex-Related Differences in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results of 2 Prospective Cohort Studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aniwan S, Eakpongpaisit S, Imraporn B, Amornsawadwatana S, Rerknimitr R. Infliximab stopped severe gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2730-2734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Borghini R, Villanacci V, Oberti A, Caronna R, Trecca A. Long-term Effects of Teduglutide on Intestinal Mucosa in a Patient With Crohn's Disease and Short Bowel Syndrome: Clinical, Endoscopic and Histological Data Compared. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:e152-e153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Belaiche J, Louis E, D'Haens G, Cabooter M, Naegels S, De Vos M, Fontaine F, Schurmans P, Baert F, De Reuck M, Fiasse R, Holvoet J, Schmit A, Van Outryve M. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn's disease: characteristics of a unique series of 34 patients. Belgian IBD Research Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2177-2181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Paragomi P, Moradi K, Khosravi P, Ansari R. Severe Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in a Patient with Crohn's Disease: a Case Report and the Review of Literature. Acta Med Iran. 2015;53:728-730. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kim E, Kang Y, Lee MJ, Park YN, Koh H. Life-threatening lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage in pediatric Crohn's disease. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013;16:53-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Papi C, Gili L, Tarquini M, Antonelli G, Capurso L. Infliximab for severe recurrent Crohn's disease presenting with massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:238-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kevans D, Murthy S, Mould DR, Silverberg MS. Accelerated Clearance of Infliximab is Associated With Treatment Failure in Patients With Corticosteroid-Refractory Acute Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:662-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brandse JF, van den Brink GR, Wildenberg ME, van der Kleij D, Rispens T, Jansen JM, Mathôt RA, Ponsioen CY, Löwenberg M, D'Haens GR. Loss of Infliximab Into Feces Is Associated With Lack of Response to Therapy in Patients With Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:350-5.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ma D, Wong W, Aviado J, Rodriguez C, Wu H. Safety and Tolerability of Accelerated Infliximab Infusions in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:352-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Johnston A, Natarajan S, Hayes M, MacDonald E, Shorr R. Accelerated induction regimens of TNF-alpha inhibitors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gibson DJ, Doherty J, McNally M, Campion J, Keegan D, Keogh A, Kennedy U, Byrne K, Egan LJ, McKiernan S, MacCarthy F, Sengupta S, Sheridan J, Mulcahy HE, Cullen G, Slattery E, Kevans D, Doherty GA. Comparison of medium to long-term outcomes of acute severe ulcerative colitis patients receiving accelerated and standard infliximab induction. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020;11:441-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gibson DJ, Heetun ZS, Redmond CE, Nanda KS, Keegan D, Byrne K, Mulcahy HE, Cullen G, Doherty GA. An accelerated infliximab induction regimen reduces the need for early colectomy in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:330-335.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, Branche J, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn's disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:644-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Comerford LW, Bickston SJ. Treatment of luminal and fistulizing Crohn's disease with infliximab. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33:387-406, xi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rofaiel R, Kohli S, Mura M, Hosseini-Moghaddam SM. A 53-year-old man with dyspnoea, respiratory failure, consistent with infliximab-induced acute interstitial pneumonitis after an accelerated induction dosing schedule. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |