Published online Jan 14, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i2.725

Peer-review started: August 19, 2021

First decision: November 1, 2021

Revised: November 12, 2021

Accepted: December 7, 2021

Article in press: December 7, 2021

Published online: January 14, 2022

Processing time: 145 Days and 23.8 Hours

Pneumocephalus is a rare complication presenting in the postoperative period of a thoracoscopic operation. We report a case in which tension pneumocephalus occurred after thoracoscopic resection as well as the subsequent approach of surgical management.

A 66-year-old man who received thoracoscopic resection to remove an intratho

This report and literature review indicated that the risk of developing a tension pneumocephalus cannot be ignored and should be monitored carefully after thoracoscopic tumor resection.

Core Tip: Pneumocephalus is a rare complication that presents during the postoperative period following a thoracoscopic resection of spinal dumbbell tumors. Here, we present a potential method for resolving tension pneumocephalus and present our detailed experiences following the thoracoscopic resection of a posterior mediastinal dumbbell tumor, together with a review of the literature. The risks of experiencing pneumocephalus following thoracoscopic resection for a spinal tumor cannot be neglected because intraoperative repair is difficult to assess.

- Citation: Chang CY, Hung CC, Liu JM, Chiu CD. Tension pneumocephalus following endoscopic resection of a mediastinal thoracic spinal tumor: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(2): 725-732

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i2/725.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i2.725

Tension pneumocephalus (TP) is defined as the presence of air in the intracranial space, causing intracranial hypertension and a mass effect[1,2]. The clinical presentation of TP may include headache, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, aphasia, hemiparesis, altered levels of consciousness, and frontal lobe syndrome[1-4]. Because most symptoms associated with TP are non-specific, the diagnosis primarily depends on imaging findings. The formation of TP can be fatal if not diagnosed early and treated properly[5].

Spinal dumbbell tumors accounted for 17% to 22% of all spinal cord tumors according to previous reports[6,7] and are classified as epidural, intradural, or paravertebral depending on the locations involved[6]. Laminectomy with costotransversectomy has been presented as an effective method for the resection of thoracic dumbbell tumors involving large intraspinal and paraspinal regions[8,9]. Anterior approaches may also be feasible for the treatment of tumors that only involve the paraspinal region[10]. However, complications may develop after surgery, including pleural injury, bleeding, damage to the spinal cord, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage[8-10]. Few cases have been reported regarding the occurrence and management of pneumocephalus following the thoracoscopic resection of a neurogenic tumor[11,12]. We report a case in which TP developed after a thoracoscopic resection and describe the subsequent surgical management approach.

A 66-year-old man described suffering from severe headache and vomiting, which became exaggerated with postural changes, following treatment with thoracoscopic resection to remove a neurogenic tumor.

The symptoms appeared starting on the 7th postoperative day.

The patient was previously diagnosed with a thoracic spinal dumbbell tumor.

None.

The patient was sent to our emergency department, where a neurological examination showed clear consciousness (Glasgow coma scale: E4V5M6) with drowsiness and disorientation, no cranial nerve abnormalities, and full muscle power in all four limbs. Preoperatively, the patient’s body temperature was 36.4 °C, blood pressure was 145/73 mmHg, heart rate was 90 bpm, and respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute. The patient had normal heart and clear lungs sounds.

Before the surgery, the patient presented with normal white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts, and slight decreases in red blood cell count (3.48 × 106/µL), hemoglobin concentration (11.0 g/dL), and hematocrit level (31.7%) were detected.

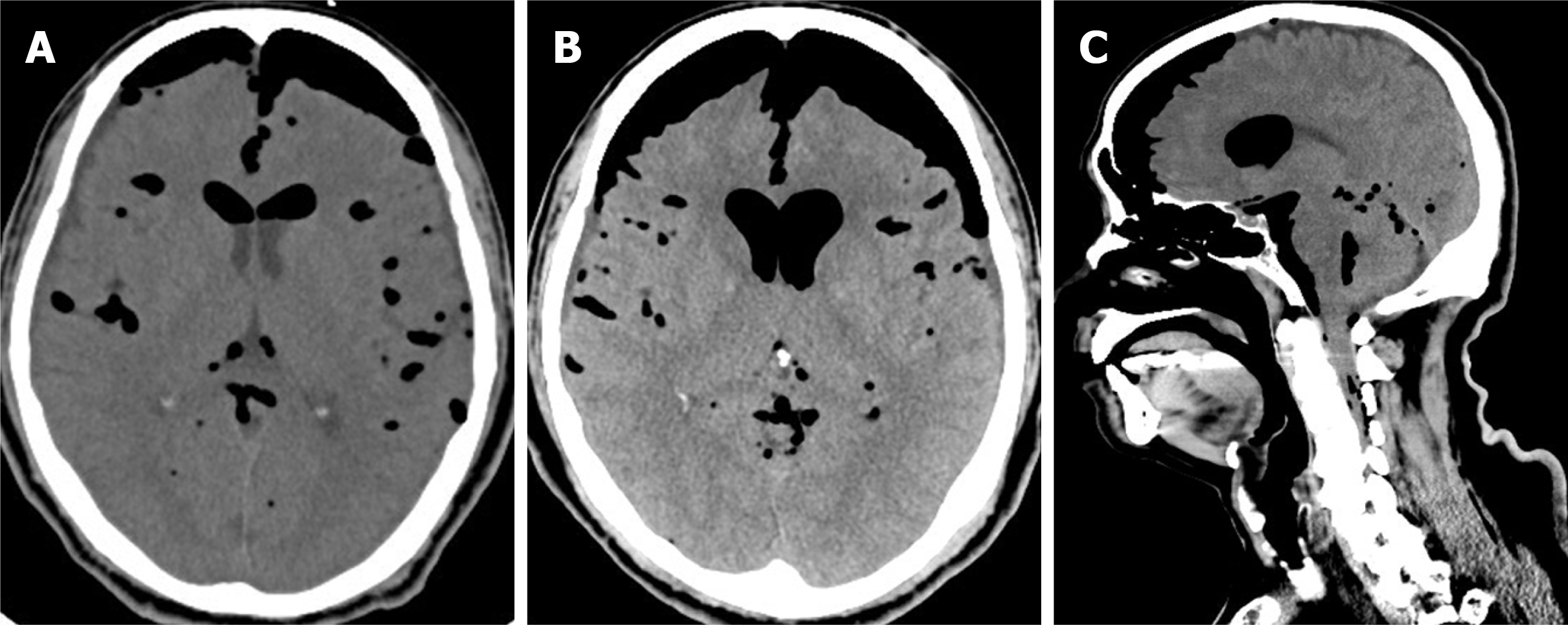

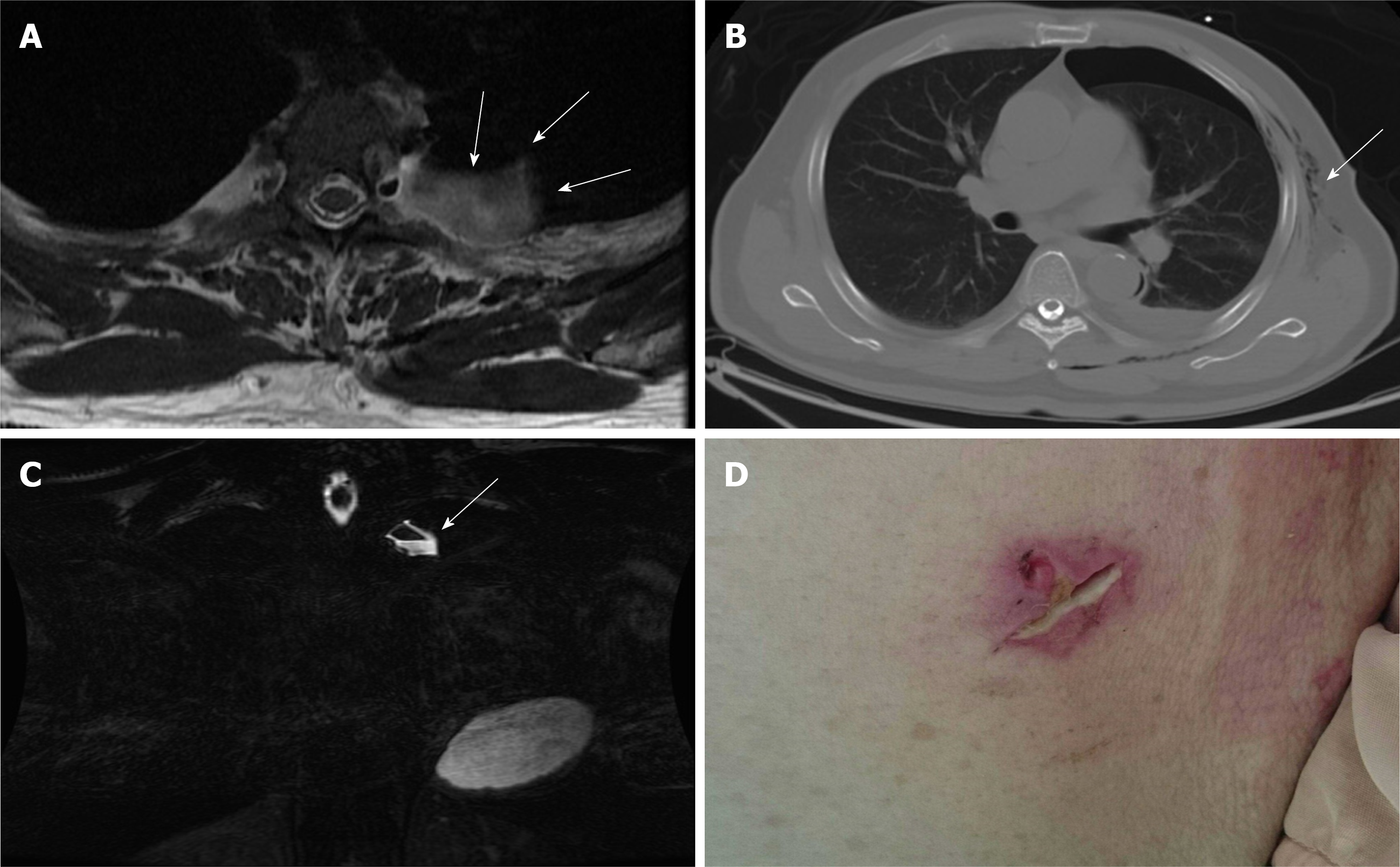

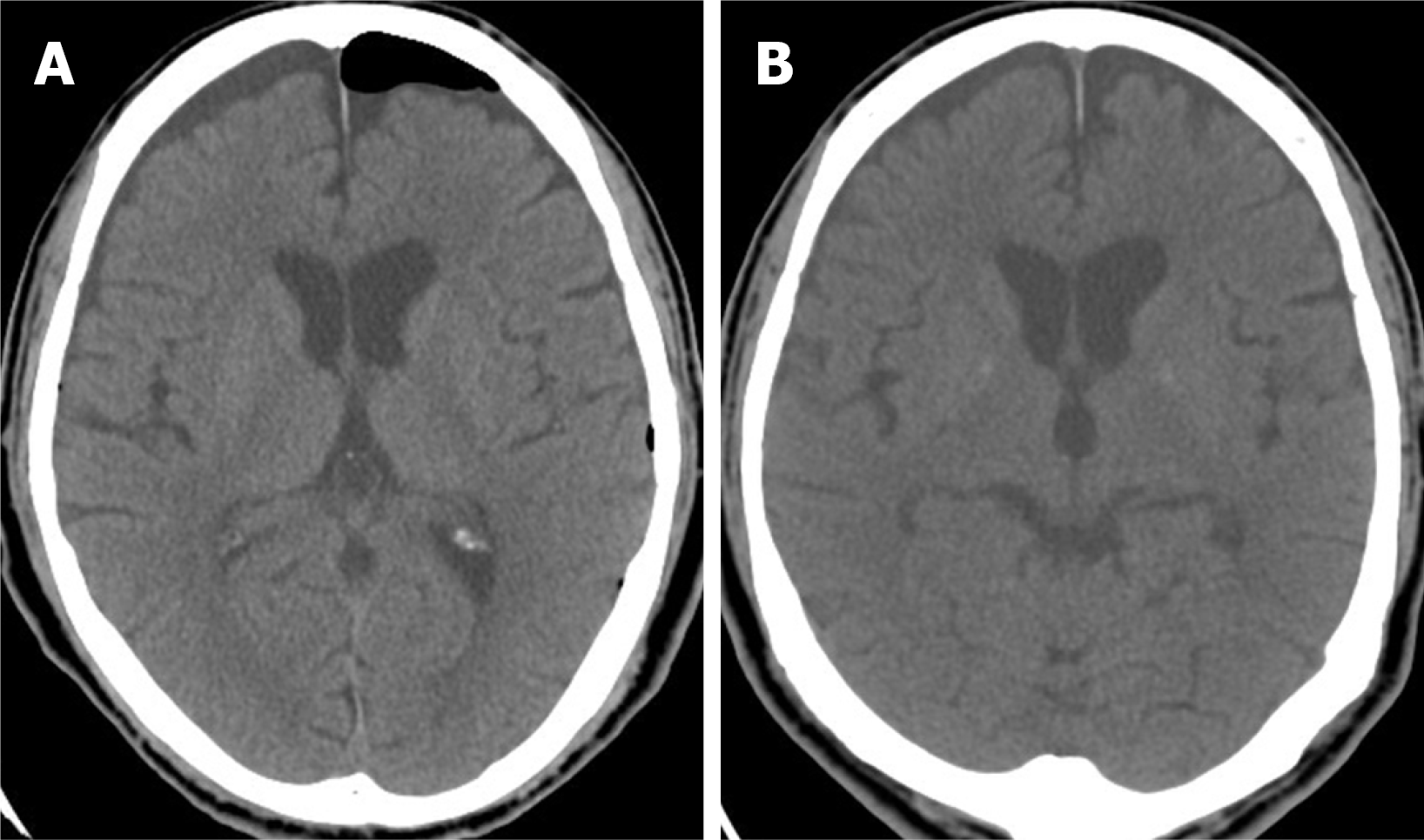

A brain computed tomography scan demonstrated TP and pneumoventricle with the air extending down into the intraspinal space, and the progression of TP was found 3 d after his admission to the intensive care unit (Figure 1). A magnetic resonance imaging scan of the thoracic spine disclosed a left T2/T3 pseudomeningocele with air-fluid level, while a chest computed tomography demonstrated pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema around the poorly healing previous thoracoscopic access wound (Figure 2). The thoracic spinal neurofibroma had been almost totally removed but was complicated with pneumothorax, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, and TP.

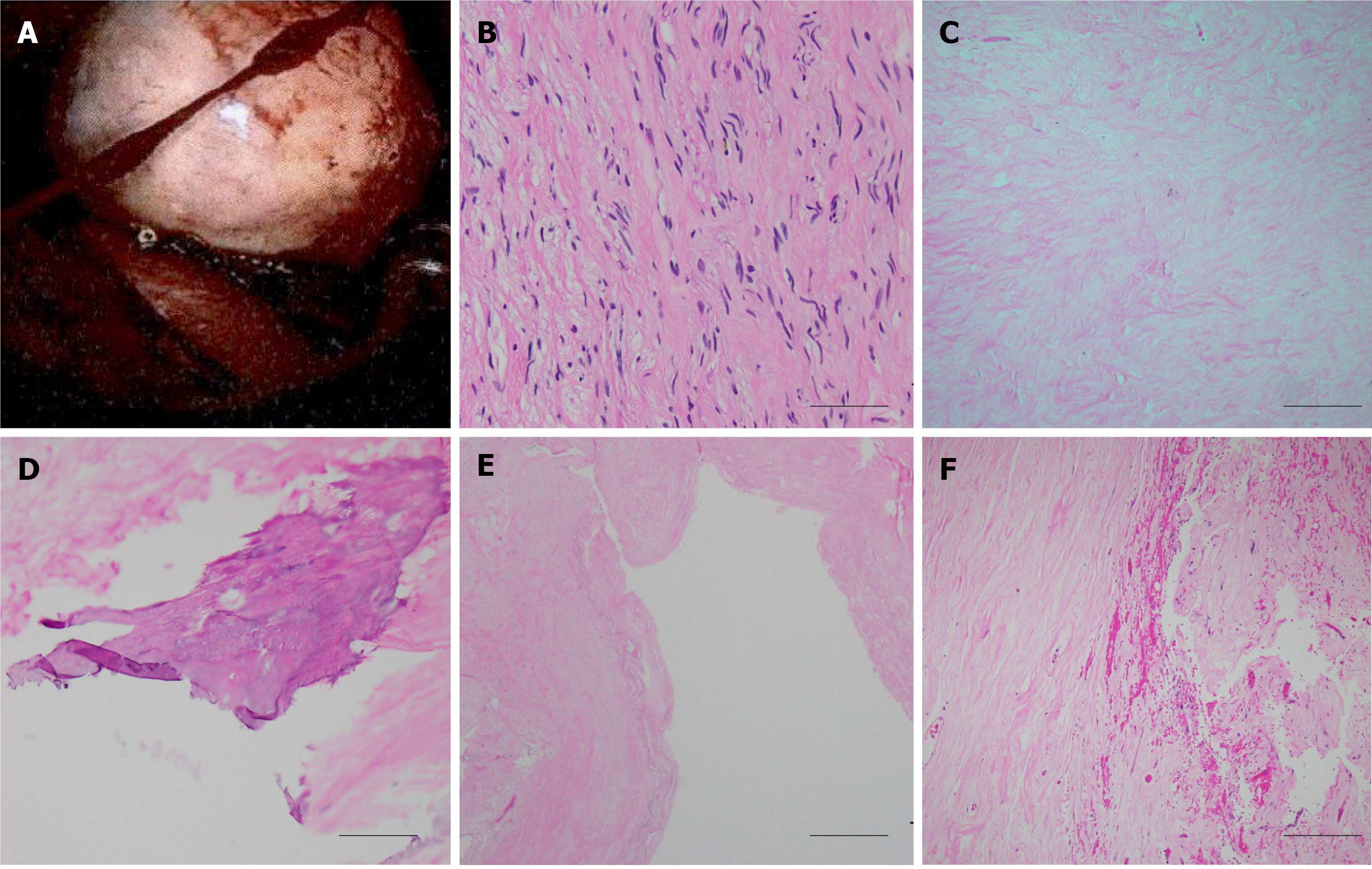

The tumor was pathologically proven to be a neurogenic tumor consisting of neurofibroma (Figure 3). According to the postoperative microscopic examination, the cyst contained chronic inflammation of tissue and no residual tumor.

The presented case was diagnosed with tension pneumocephalus after a thoracoscopic resection to remove a neurogenic tumor.

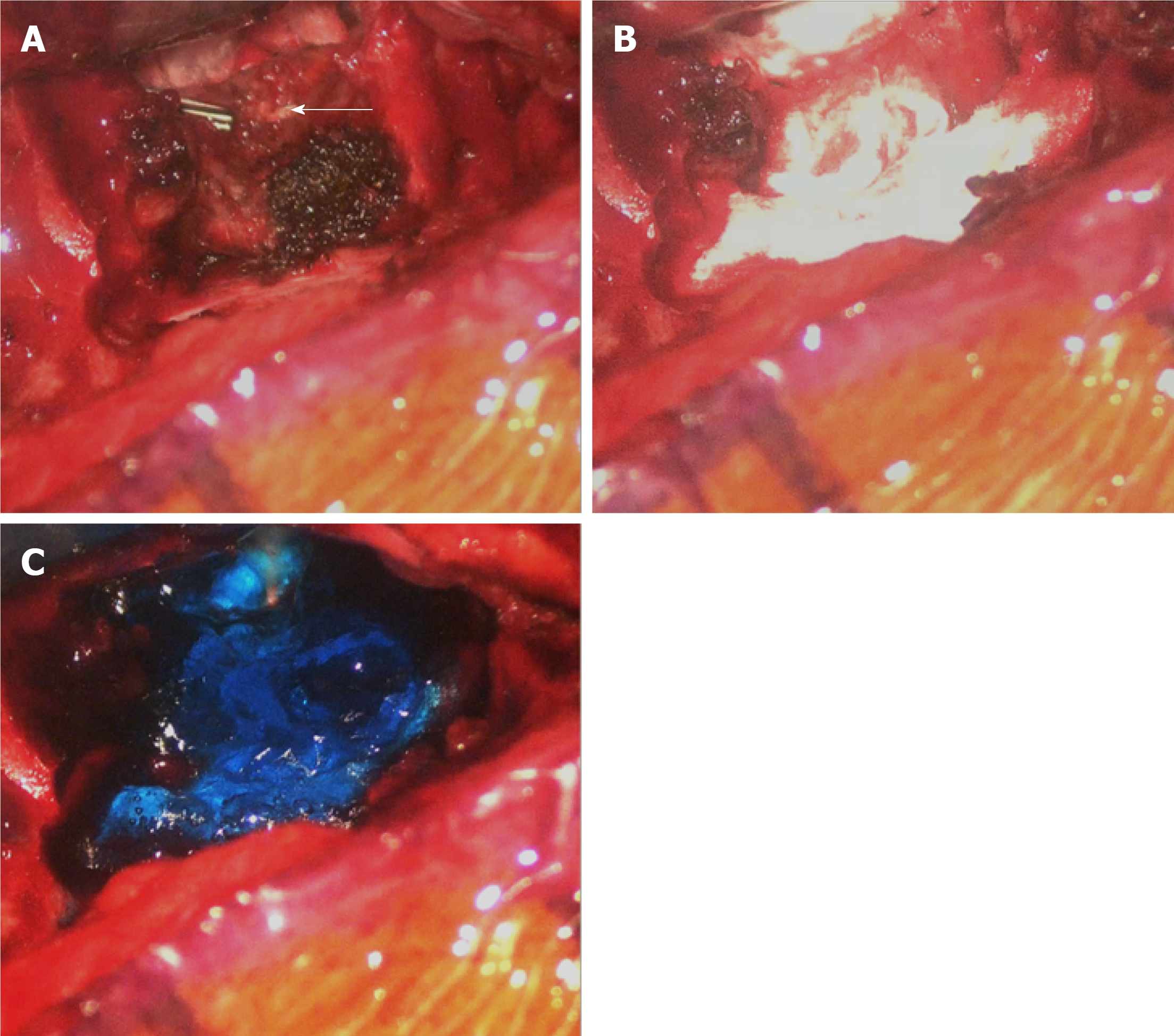

He then was admitted to the intensive care unit for further close monitoring and medical treatments including full hydration, prophylactic antibiotics use, O2 supplementation, lying absolutely flat, and primary suturing and debridement of the chest wound. However, the symptoms did not improve. Thus, surgical treatments were performed to repair the CSF leakages. Following a left T2-3 hemilaminectomy and costotransversectomy, a cystic meningocele was found. After the cyst pouch was totally removed, the previous remnant tumor stump and surgical clip were explored meticulously. CSF leaking from the surgical clip near the dura was disclosed. The leakage site was wrapped with autologous fat, gelfoam, tissue glue, and duraseal in a layer-by-layer manner (Figure 4). Finally, the wound was closed in a layer-by-layer manner with a Jackson-Pratt tube that was left in the surgical field.

At the 2-wk follow-up and evaluation, the patient denied experiencing any further headaches. The follow-up brain computed tomography scan showed resolution of the pneumocephalus, pneumoventricle, pneumothorax, and pneumospine (Figure 5).

The reported theories of pneumocephalus development include the “ball-valve theory” and “inverted soda bottle effect”[13,14]. The possible mechanisms to develop pneumocephalus after thoracoscopic resection include dural tearing with persistent cerebrospinal fluid leakage, such that air can gain access from the leakage site to the intradural space and reach the cranial cavity. The negative pressure produced by chest tube suction can even deteriorate the CSF extravasation. On the other hand, an upright head position also allows the air to easily enter the intradural space from the leakage site. Relatedly, in our case, a poorly healing thoracoscopic access wound resulted in pneumothorax and an aggravating pneumocephalus. Based on the imaging results of the current case, TP was indicated by two imaging characteristics. One, the “Mt. Fuji sign,” means that subdural air with increased tension is separating and compressing the bilateral frontal lobes and widening the interhemispheric space, such that the resulting image resembles the silhouette of Mt. Fuji. The other, the “air bubble sign,” indicates that multiple air bubbles are scattered through the cistern, with these air bubbles putatively entering the subarachnoid space due to tearing of the arachnoid membrane caused by increased tension in the subdural space[2,3]. This appeared to apply in our case, with the source of intracranial air being a spinal dural defect that resulted in air also being apparent in the spinal cord, ventricle, and basal cistern[12].

We performed the literature review using a search of English literature from PubMed, in which the source of databases ranged from 2000 to 2019. The key words and criteria for search engine was represented as “pneumocephalus [title] AND spinal tumor” where 11 results were generated. We further summarized the reported cases in which pneumocephalus developed after surgical treatments for spinal or posterior mediastinal tumor and specified their subsequent interventions (Tables 1, 2). Though only 23 cases in which pneumocephalus developed after surgical treatments for spinal or posterior mediastinal tumor had been reported within the recent 10 years, most patients can be treated only by conservative medical therapeutic strategies, including highly concentrated O2 supplementation to accelerate the resorption of intracranial air, bed rest with the head laid flat to minimize CSF leakage from the dural defect, avoidance of the Valsalva maneuver, and prophylactic antibiotics use if meningitis is highly suspected (Tables 1, 2). Surgical intervention consisting of the evacuation of the intracranial air and repair of the dural defect is indicated when the above conservative treatments fail, when the recurrence of pneumocephalus occurs, or when there are signs of increasing intracranial pressure[1-4,12]. In our case for progressive pneumocephalus, we preferred to conduct surgical intervention rather than conservative treatment. The direct method of dura repair was chosen in consideration to the developing CSF fistula. Then, the intracranial air was evacuated until the CSF leakage site was sealed completely. Initial frontal burr hole decompression for pneumocephalus was demonstrated in a similar case for rapid consciousness change and cranial nerve palsy under the impression of increased intracranial pressure signs, of which the clinical signs were improved postoperatively[12]. In our opinion, the direct method for dural repair can obliterate the origin of CSF leakage and fistula formation. Thus, the pneumocephalus may be absorbed spontaneously as long as there is no further air getting access[15].

| Ref. | Article type | Cases with pneumocephalus | Histology | Spinal region | Relation to dura |

| Trujillo-Reyes et al, 2014 | Case report | 1/1 | Schwannoma | Thoracic | ND |

| Huang et al, 2005 | Case report | 1/1 | Neurilemmoma | Thoracic | ND |

| Nam et al, 2019 | Case series | 18/20 | Schwannoma (n = 16)/ Miningioma (n = 4) | Cervical (15%)Thoracic (60%)Lumbar (25%) | IDEM |

| Kim et al, 2008 | Case report | 1/1 | Myxopapillary ependymoma | Lumbar | IDEM |

| Özdemir et al, 2017 | Case report | 1/1 | ND | Lumbar | IDEM |

| Bilsky et al, 2000 | Case report | 1/3 | Neurofibroma | Thoracic | ND |

| Ref. | Surgical approach | Clinical symptoms | CSF leakage | Interventions |

| Trujillo-Reyes et al, 2014 | VATS | Headache, vomiting | ND | Bed rest, oxygen |

| Huang et al, 2005 | VATS | Headache, progressive loss of consciousness | Postoperative chest tube drainage amount increased | Bilateral frontal burr hole, Trendelenburg position |

| Nam et al, 2019 | Posterior (laminectomy+ durotomy) | Headache | Intraoperative duratomy and primary suture with artificial dural and fibroblastic glue | Bed rest, analgesics |

| Kim et al, 2008 | Posterior (laminectomy+ durotomy) | Headache, restless | Intraoperative duratomy and primary suture with fibroblastic glue | Bed rest, hydration |

| Özdemir et al, 2017 | Posterior (laminectomy + durotomy) | Headache, nausea, vomiting | ND | Bed rest, hydration |

| Bilsky et al, 2000 | Posteriorlateral thoracotomy | Lethargy, confusion | Postoperative chest tube drainage amount increased | Discontinue chest tube, bed rest |

Intraoperative primary repair with suturing is highly recommended for preventing postoperative CSF leakage[16]. However, the primary closure of a durotomy may be difficult because of its location (e.g., in the case of ventral or far-lateral durotomies), a large dural defect, poor tensile strength of the dura, or a minimal invasive wound limiting the exposure and access[15]. Several alternative methods of durotomy repair have been described. For example, an additional dorsal durotomy for far-lateral or dorsal defects can allow such defects to be more easily visualized and plugged with autograft or suturing[15], while autograft coverage with dural sealant in cases of durotomies that cannot be repaired primarily due to limited visibility or access[15,17], an aneurysm clip, or a titanium clip have also been reported[18,19]. In our case, as the CSF leakage might have derived from the previous endoscopically clipped tumor stump near the dural sac at the T3 level, such that it would have been difficult to perform a primary suture repair. Thus, we plugged and wrapped the stump with an autograft of fat, tissue glue, gelfoam, and duraseal (Figure 4).

The risk of getting a pneumocephalus after thoracoscopic resection of a spinal tumor cannot be neglected since the intraoperative repair is hard to access. The direct approach for dural repair may be an attemptable way to eliminate the CSF leakages.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Elpek GO, Kim JW S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | Kankane VK, Jaiswal G, Gupta TK. Posttraumatic delayed tension pneumocephalus: Rare case with review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016;11:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schirmer CM, Heilman CB, Bhardwaj A. Pneumocephalus: case illustrations and review. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:152-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ishiwata Y, Fujitsu K, Sekino T, Fujino H, Kubokura T, Tsubone K, Kuwabara T. Subdural tension pneumocephalus following surgery for chronic subdural hematoma. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:58-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Harvey JJ, Harvey SC, Belli A. Tension pneumocephalus: the neurosurgical emergency equivalent of tension pneumothorax. BJR Case Rep. 2016;2:20150127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dabdoub CB, Salas G, Silveira Edo N, Dabdoub CF. Review of the management of pneumocephalus. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ozawa H, Kokubun S, Aizawa T, Hoshikawa T, Kawahara C. Spinal dumbbell tumors: an analysis of a series of 118 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:587-93. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hirano K, Imagama S, Sato K, Kato F, Yukawa Y, Yoshihara H, Kamiya M, Deguchi M, Kanemura T, Matsubara Y, Inoh H, Kawakami N, Takatsu T, Ito Z, Wakao N, Ando K, Tauchi R, Muramoto A, Matsuyama Y, Ishiguro N. Primary spinal cord tumors: review of 678 surgically treated patients in Japan. A multicenter study. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:2019-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li Y, Wang B, Li L, Lü G. Posterior surgery versus combined laminectomy and thoracoscopic surgery for treatment of dumbbell-type thoracic cord tumor: A long-term follow-up. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;166:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ando K, Imagama S, Ito Z, Tauchi R, Muramoto A, Matsui H, Matsumoto T, Ishiguro N. Removal of thoracic dumbbell tumors through a single-stage posterior approach: its usefulness and limitations. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18:380-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen X, Ma Q, Wang S, Zhang H, Huang D. Surgical treatment of posterior mediastinal neurogenic tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119:807-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Trujillo-Reyes JC, Rami-Porta R, Navarro AK, Belda-Sanchis J. Tension pneumocephalus: a rare complication after resection of a neurogenic tumour by thoracoscopic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang YK, Lu MS, Liu YH, Wu YC, Liu HP. Pneumocephalus after thoracoscopic excision of posterior mediastinal tumor. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:848-851. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Dandy WE. Pneumocephalus (intracranial pneumatocele or aerocele). Archives of Surgery. 1926;12:949-82. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | HOROWITZ M. INTRACRANIAL PNEUMOCOELE. AN UNUSUAL COMPLICATION FOLLOWING MASTOID SURGERY. J Laryngol Otol. 1964;78:128-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barber SM, Fridley JS, Konakondla S, Nakhla J, Oyelese AA, Telfeian AE, Gokaslan ZL. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks after spine tumor resection: avoidance, recognition and management. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Dafford EE, Anderson PA. Comparison of dural repair techniques. Spine J. 2015;15:1099-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Epstein NE. A review article on the diagnosis and treatment of cerebrospinal fluid fistulas and dural tears occurring during spinal surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:S301-S317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Beier AD, Barrett RJ, Soo TM. Aneurysm clips for durotomy repair: technical note. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2010;66:E124-E125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Faulkner ND, Finn MA, Anderson PA. Hydrostatic comparison of nonpenetrating titanium clips vs conventional suture for repair of spinal durotomies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:E535-9. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |