Published online Jul 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6722

Peer-review started: February 28, 2022

First decision: April 8, 2022

Revised: April 14, 2022

Accepted: April 24, 2022

Article in press: April 24, 2022

Published online: July 6, 2022

Processing time: 115 Days and 13.1 Hours

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) is a rare cystic lung disease usually affecting young adults. It is predicted that PLCH is a lung tumor precursor associated with dysfunction of the myeloid dendritic cells in the lung.

A 70-year-old male patient presented with chronic cough and sputum. He had symptoms for 5 years and described shortness of breath on exertion for the previous 3 years. He had a 60 packs/year smoking history. Computerized tomography of the thorax revealed an 11-mm nodule in the right lung lower lobe superior segment and a 7-mm nodule in the right lung lower lobe poster basal segment. Those two nodules were resected by means of right thoracoscopic surgery. Pathological evaluation revealed a squamous cell carcinoma and PLCH.

Coexistent squamous cell carcinoma and PLCH suggest possible association between PLCH and lung cancer.

Core Tip: The BRAF mutation is associated with a number of tumors, it is thought that Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) may be a precursor of malignancy. In this case, the diagnosis of PLCH concurrently with the diagnosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma and the detection of BRAF mutation supported this hypothesis.

- Citation: Gencer A, Ozcibik G, Karakas FG, Sarbay I, Batur S, Borekci S, Turna A. Two smoking-related lesions in the same pulmonary lobe of squamous cell carcinoma and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(19): 6722-6727

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i19/6722.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6722

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) is a rare cystic interstitial lung disease usually affecting young adults and is a type of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) disease group[1]. It is the type which remains isolated in the lung, and rarely shows a progressive course[2]. Although its incidence and prevalence are not exactly known, it constitutes 3%-5% of cases of diffuse lung diseases, and smoking is considered a predisposing factor[3,4].

PLCH is considered an inflammatory myeloid neoplasm based on the presence of somatic oncogenic mutations in pulmonary CD1a dendritic cells[5]. Three known factors play a role in its pathophysiology: (1) BRAF V600E and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) 2K1 somatic mutations in MAPK pathway; (2) Smoking; and (3) Dysfunction of the myeloid dendritic cells[6,7].

In this report, a patient with a concurrent diagnosis of PLCH and squamous cell carcinoma was presented.

A seventy-year-old male patient presented with a history of intermittent cough, white sputum, and shortness of breath triggered by exercise (modified Medical Research Council 3), and was admitted to the outpatient clinic.

Intermittent cough and white sputum for a period of 5 years, and shortness of for 3 years. He had taken sulbactam ampicillin 2 × 440/294 mg for 14 d and gemifloxacin for 7 d and had consulted a physician twice during the previous 2 mo because of recurrent complaints.

The patient had a medical history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for 15 years and coronary artery disease for 4 years.

He was a current smoker who smoked 60 packs of cigarettes/year. His father had a diagnosis of lung cancer.

Lung examination findings included a prolonged bilateral expiratory phase, while physical examinations of his other systems were found to be within normal limits. His body temperature was 36.9 °C, pulse rate 86 bpm at rest, blood pressure 130/85 mmHg, respiratory rate 18/min, and oxygen saturation 98% while the patient was breathing room air.

Laboratory examination revealed that his hemoglobin level stood at 12 g/dL and his hematocrit level was 35.4%, indicating mild anemia. The pulmonary function test revealed that the forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) was 3060 mL (103%), forced vital capacity (FVC) was 4130 mL (107%), and the FEV1/FVC ratio was 74%. The patient’s shortness of breath triggered by exercise was interpreted as secondary to his chronic diseases. Gram staining of the sputum sample showed many epithelial cells and a small amount of leukocytes. The Genexpert tuberculosis-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test could not be performed due to technical reasons. Acid-fast staining of the sputum yielded negative results three separate times. There was no growth in the culture of bacteria including of tuberculosis, bacillus, or fungi.

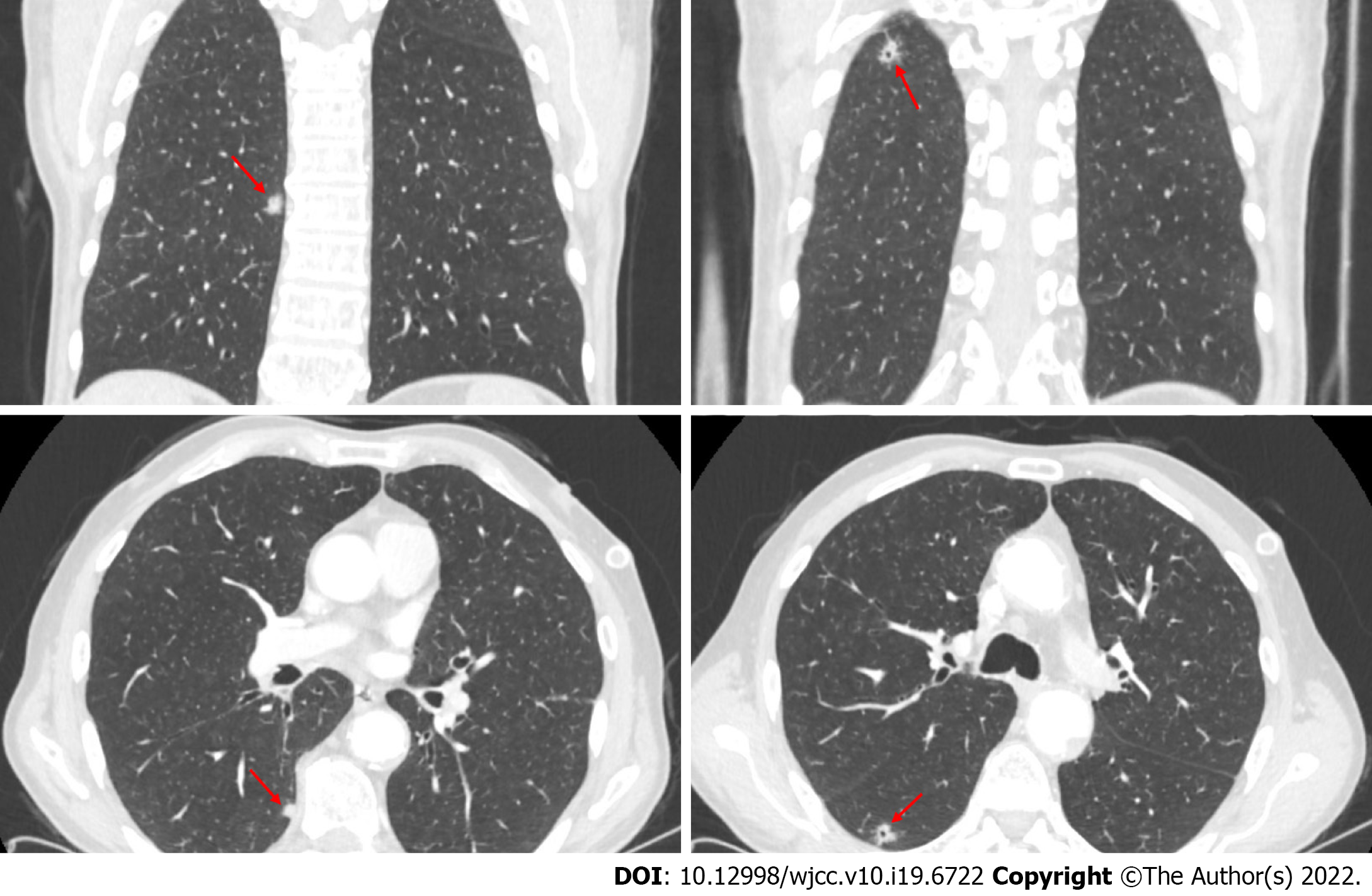

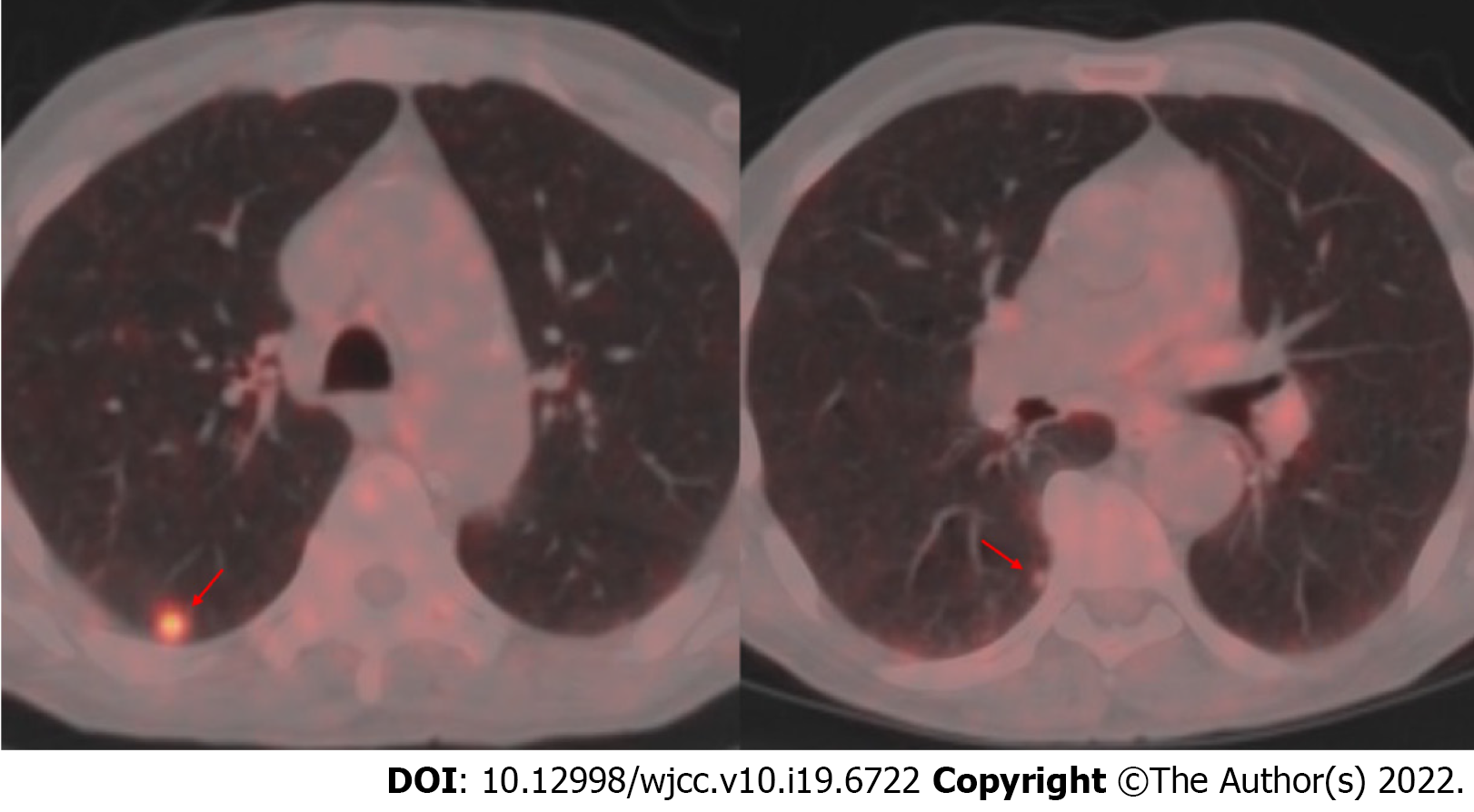

There were signs of bilaterally increased aeration on plain chest radiography. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax revealed densities of bilateral apical pleuroparenchymal fibrotic lesions, and paraseptal and centrilobular emphysema in the upper lobes of both lungs, an 11-mm nodule with cavitation in the superior segment of the right lung lower lobe, and a 7-mm nodule the lower lobe posterior basal segment of the lung (Figure 1). Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) revealed a 10-mm nodular lesion in the superior part of the right lung lower lobe with a maximum standard uptake value (SUV max) of 6.43, and minimal focal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the 7-mm nodular lesion in the posterior basal part of the right lung lower lobe (Figure 2).

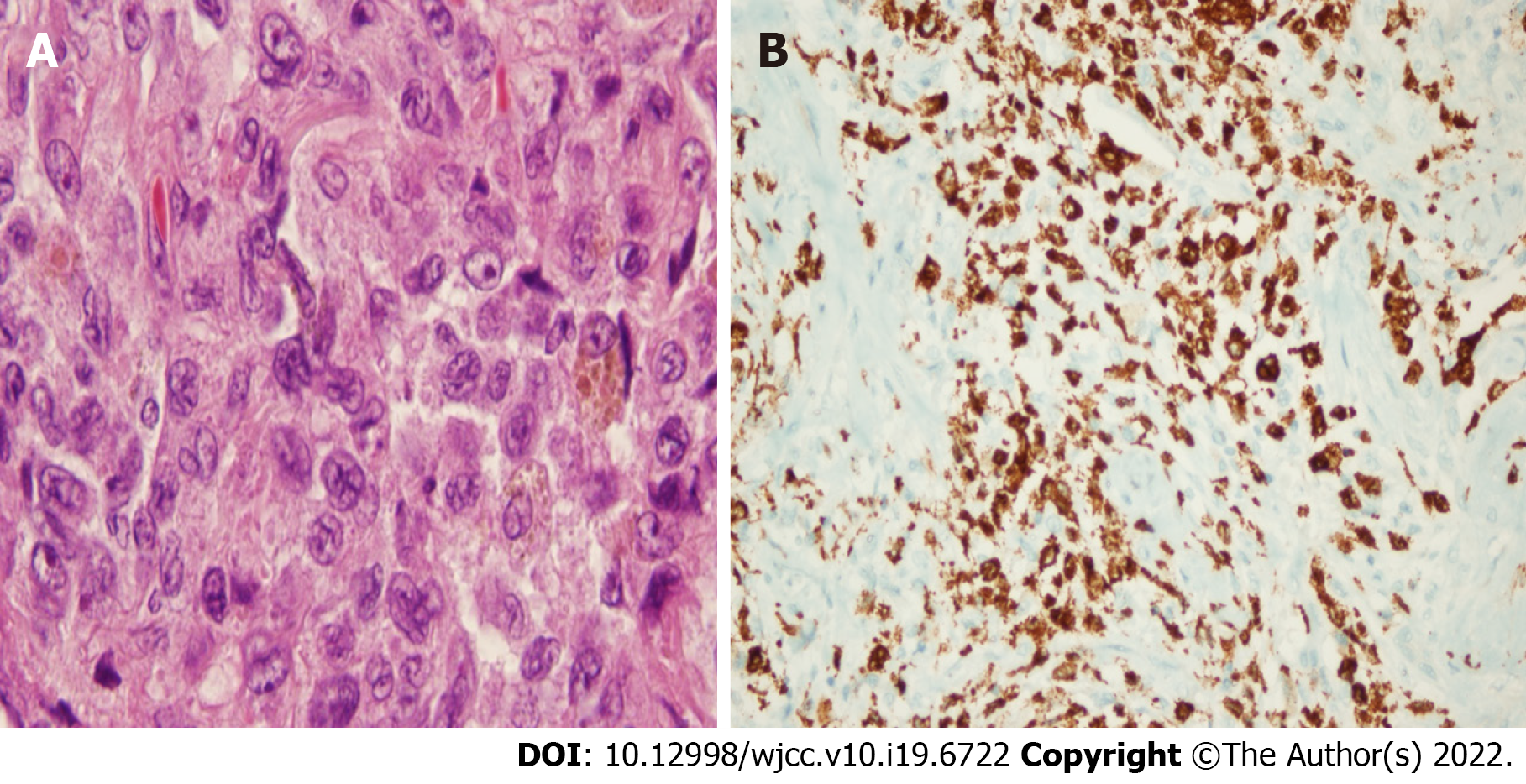

The wedge resection of the right lower lobe superior and posterior basal segments were performed. Pathologic examination revealed a squamous cell carcinoma with dimensions of 1.5 cm × 1 cm × 0.7 cm (T1b), in the wedge resection material of the right lung lower lobe superior segment, and a Langerhans cell histiocytosis at 0.7 cm in diameter in the wedge resection material of the right lung lower lobe posterior basal segment (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical analyses revealed positive staining with S100 protein, CD1a, and Langerin, while real-time PCR identified a BRAF V600E mutation. Gene detection was not performed for squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis was diagnosed.

A single-incision video thoracoscopic wedge resection of the right lower lobe superior was performed while posterior basal segments were performed under general anesthesia.

The patient was informed of his disease, the importance of quitting smoking was emphasized, he was given support to quit. He was called for follow-up in terms of clinical and respiratory functions 6 mo later.

A case was presented herein which was found to feature both squamous cell carcinoma and LCH in the right lower lobe, simultaneously. LCH is an idiopathic neoplasm of myeloid dendritic cells[8]. It comes in two clinical forms: the first type is seen in children and has a localized or systemic course and has been described in many terms over the years[7]. In 1953, Lichtenstein first described it as Histiocytosis X, and then according to the organs involved, it was named as the eosinophilic granuloma or Hand-Schüller-Christian disease or Letterer-Siwe disease[7].

Another clinical form of LCH is PLCH, seen in young adults with a history of smoking. It is an interstitial lung disease of unknown etiology, characterized by focal infiltration of Langerhans cells and exhibiting unpredictable biologic behavior[9]. It constitutes 3%-5% of diffuse parenchymal lung diseases, but its exact prevalence is not known since most of the patients are asymptomatic[9]. Probably attributable to the fact that the disease remains localized in the lungs and rarely has a progressive course ensuring that it has the best prognosis in the LCH group[10].

Dysfunction of the myeloid dendritic cells is well defined in PLCH[8]. Somatic mutations in CD1a dendritic cells and MAPK pathway, especially BRAF and MAP2K1, have been identified as having a key role in the pathogenetic mechanism of this disease by activation of this pathway[5]. The BRAF V600E mutation was first described in LCH cases in 2010[11]. Since the BRAF mutation is associated with a number of tumors, it is thought that PLCH may be a precursor of malignancy[12]. In the current case, the diagnosis of PLCH concurrently with the diagnosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma and the detection of BRAF mutation supported this hypothesis.

BRAF V600E mutation was detected in 2 of 5 patients diagnosed with PLCH with bilateral pulmonary nodules[2]. It has been emphasized that BRAF V600E mutation acts as a driver mutation for neoplastic transformation in malignant melanoma, lung, thyroid, and colonic adenocarcinomas. As in other histiocytic dendritic disorders, targeted therapies can be used through progressive cases of PLCH featuring BRAF V600E mutation[2].

In the study of Roden et al[6], BRAF V600E expression was analyzed in 79 patients, including those diagnosed with PLCH (n: 25) and extrapulmonary LCH (n: 54). In their study, the BRAF expression was found to be significantly more prevalent in the participant smokers. The BRAF V600E expression was found in 28% of the patients with PLCH and in 35% of patients with extrapulmonary LCH. In a similar analysis, the BRAF V600E mutation was demonstrated in 50% of 26 pulmonary LCH patients and 38% of 37 extrapulmonary LCH patients[13].

Based on the occurrence of BRAF mutations in non-small cell lung cancers and the definition of targeted therapies, in the study conducted by Paik et al[14] on 697 patients with lung adenocarcinoma, BRAF V600E mutations were detected in 50%, G469A in 39%, and D594G mutations in 11% of the patients. It was emphasized that the BRAF mutation was found in 3% of the patients with lung adenocarcinoma and was generally detected in smokers. In the case herein, the BRAF V600E mutation was found in the patient, who also received a concurrent diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma and PLCH.

Alden et al[15] describe a patient suffering from early-stage lung adenocarcinoma who developed bilateral pulmonary nodules in the case report. Histopathologic examination revealed Langerhans cell histiocytosis, positive for CD1a, Langerin, and S100 and genomic sequencing identified a BRAF V600E mutation. Although pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis is rarely diagnosed in the setting of lung cancer, reports in association with primary lung cancers do exist[16].

The presence of somatic oncogenic mutations such as BRAF in patients diagnosed with PLCH suggests that PLCH may be a precursor to malignancy. Periodic follow-up, preferably with low-dose chest CT and encouragement of smoking cessation, is recommended in patients with PLCH.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu W, China; Li HX, China S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Jouenne F, Chevret S, Bugnet E, Clappier E, Lorillon G, Meignin V, Sadoux A, Cohen S, Haziot A, How-Kit A, Kannengiesser C, Lebbé C, Gossot D, Mourah S, Tazi A. Genetic landscape of adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis with lung involvement. Eur Respir J. 2020;55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yousem SA, Dacic S, Nikiforov YE, Nikiforova M. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: profiling of multifocal tumors using next-generation sequencing identifies concordant occurrence of BRAF V600E mutations. Chest. 2013;143:1679-1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gaensler EA, Carrington CB. Open biopsy for chronic diffuse infiltrative lung disease: clinical, roentgenographic, and physiological correlations in 502 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1980;30:411-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vassallo R, Harari S, Tazi A. Current understanding and management of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Thorax. 2017;72:937-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brown NA, Elenitoba-Johnson KSJ. Clinical implications of oncogenic mutations in pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Roden AC, Hu X, Kip S, Parrilla Castellar ER, Rumilla KM, Vrana JA, Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Yi ES. BRAF V600E expression in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: clinical and immunohistochemical study on 25 pulmonary and 54 extrapulmonary cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:548-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Harmon CM, Brown N. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: A Clinicopathologic Review and Molecular Pathogenetic Update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:1211-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-Cell Histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR, Decker PA, Limper AH. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:484-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McClain KL, Gonzalez JM, Jonkers R, De Juli E, Egeler M. Need for a cooperative study: Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis and its management in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;39:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, Calicchio ML, Kuo FC, Ligon AH, Stevenson KE, Kehoe SM, Garraway LA, Hahn WC, Meyerson M, Fleming MD, Rollins BJ. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 783] [Cited by in RCA: 856] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, Davis N, Dicks E, Ewing R, Floyd Y, Gray K, Hall S, Hawes R, Hughes J, Kosmidou V, Menzies A, Mould C, Parker A, Stevens C, Watt S, Hooper S, Wilson R, Jayatilake H, Gusterson BA, Cooper C, Shipley J, Hargrave D, Pritchard-Jones K, Maitland N, Chenevix-Trench G, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Palmieri G, Cossu A, Flanagan A, Nicholson A, Ho JW, Leung SY, Yuen ST, Weber BL, Seigler HF, Darrow TL, Paterson H, Marais R, Marshall CJ, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Futreal PA. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7459] [Cited by in RCA: 7630] [Article Influence: 331.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mourah S, How-Kit A, Meignin V, Gossot D, Lorillon G, Bugnet E, Mauger F, Lebbe C, Chevret S, Tost J, Tazi A. Recurrent NRAS mutations in pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1785-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, Sima CS, Miller VA, Kris MG, Ladanyi M, Riely GJ. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2046-2051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alden SL, Swanson SJ, Nishino M, Sholl LM, Awad MM. BRAF-Mutant Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Mimicking Recurrence of Early-Stage KRAS-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;2:100127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kalchiem-Dekel O, Paulk A, Kligerman SJ, Burke AP, Shah NG, Dixon RK. Development of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a patient with established adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:E1079-E1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |