Published online Jul 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6716

Peer-review started: January 24, 2022

First decision: March 23, 2022

Revised: March 28, 2022

Accepted: May 8, 2022

Article in press: May 8, 2022

Published online: July 6, 2022

Processing time: 151 Days and 5.5 Hours

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) originates from the mesothelial and subcutaneous cells of the abdominal cavity. Its diagnose is difficult due to its nonspecific and vague symptoms, and it should be differentiated from alcoholic cirrhosis and liver and pancreatic cancers. Misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis can easily occur when MPM presents with other diseases. To the best of our know

A 63-year-old man presented to our hospital with abdominal distension for 20days. He had a history of alcohol consumption for nearly 30 years and no history of special drug use or toxic exposure. After treatment for alcoholic cirrhosis in a community hospital, his symptoms did not improve significantly. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy and surgical resection. Pathologic examination showed an epithelioid MPM. He was treated with chemotherapy and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion after surgery. Currently, he is in a stable condition and tumor recurrence has not occurred.

Misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis of MPM can easily occur because of its insidious onset. Therefore, there is a need to understand. MPM in clinical practice, make the correct diagnosis, and provide timely and effective treatment.

Core Tip: Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare disease with nonspecific and vague symptoms. MPM concurrent with alcoholic cirrhosis has not been reported previously. We report the case of a 63-year-old man who had abdominal distension and was initially diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis. His symptoms did not improve significantly after treatment for the cirrhosis. The patient then underwent exploratory laparotomy, and pathologic examination showed an epithelioid MPM. Misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis of MPM is commom because of its insidious onset. Clinicians should be aware of the disease and make a correct diagnosis so as to provide patients with timely and effective treatment. MPM concurrent with alcoholic cirrhosis is rare and requires further study.

- Citation: Liu L, Zhu XY, Zong WJ, Chu CL, Zhu JY, Shen XJ. Concurrent alcoholic cirrhosis and malignant peritoneal mesothelioma in a patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(19): 6716-6721

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i19/6716.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6716

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare malignancy originating from the peritoneal epithelium or mesothelium. The annual incidence of the tumor in the general population is 1-2 cases per million, and it was first reported in 1908[1]. In recent years, studies have shown that the incidence of the MPM in those with asbestos exposure is significantly higher than that in those without asbestos exposure[2]. Pathological and immunohistochemical examinations are the gold standards for its diagnosis. MPM has a hidden onset, and the clinical symptoms of patients are not typical; therefore, missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis may occur. Here, we here report a case where the clinical manifestations, such as abdominal distension and ascites and abdominal imaging findings, were consistent with alcoholic cirrhosis, due to which the diagnosis of MPM was missed.

A 63-year-old man presented to our hospital with a history of abdominal distension for 20 d.

The patient's abdominal distension was persistent and worsened after meals. He vomited an average of 1-2 times per day, with no coffee ground vomitus. He was diagnosed with multiple hepatic cysts, alcoholic cirrhosis, and ascites by abdominal computed tomography (CT) in a community hospital. After treatment for alcoholic cirrhosis, the patient's symptoms did not improve significantly.

The patient had a history of schizophrenia for many years, and he denied a history of other diseases and surgery. The patient also had a history of alcohol consumption for nearly 30 years, with no history of special drug use or toxic exposure. He was diagnosed with hepatic cirrhosis by a liver biopsy 3 years ago.

The patient did not report any personal and family history.

Physical examination on admission showed abdominal distension, full abdominal tenderness, and dullness in movement, but no splenomegaly was observed.

Laboratory tests results were as follows: White blood cell count 7.59 × 109/L, platelet count 507 × 109/L, hemoglobin level 105 g/L, C-reactive protein 32.29 mg/L, erythrocyte sedimentation 51 mm/h, procalcitonin 0.82 ng/mL, albumin 33.9 g/L and D-dimer level of 2.15 mg/L. Exudate was detected in the examination of ascites, and the serum ascites albumin gradient level was 9.2 g/L. Results of other laboratory tests, including carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha fetoprotein, carbohydrate antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 50, antin-uclear antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti dsDNA antibody, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, coagulation function, hepatitis B surface antigen, and hepatitis C antibody were unremarkable. Malignant tumor cells were found in the exfoliated cells of ascites.

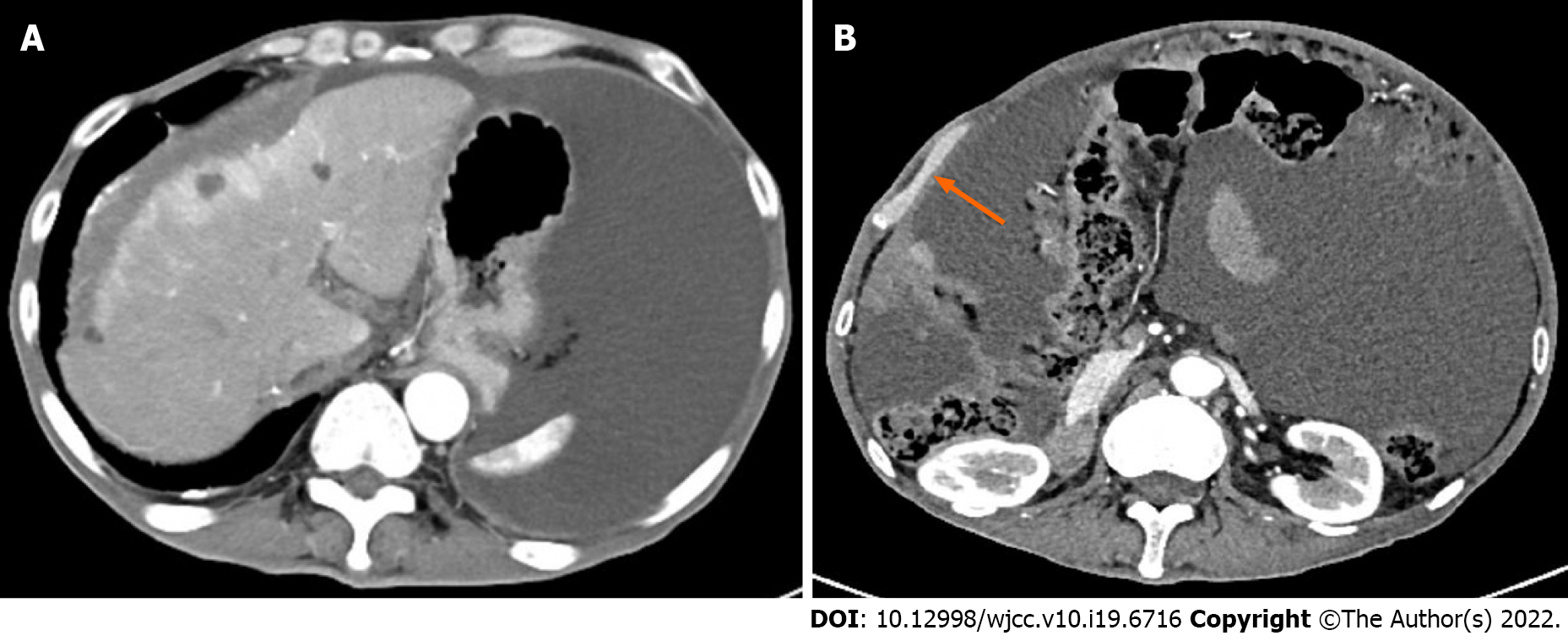

Contrast-enhanced CT scan confirmed the findings of the CT scan at the community hospital (Figure 1A). More importantly, a large amount of fluid was observed in the abdominal cavity, and the right peritoneum was irregularly thickened with nodular thickening of the greater omentum (Figure 1B).

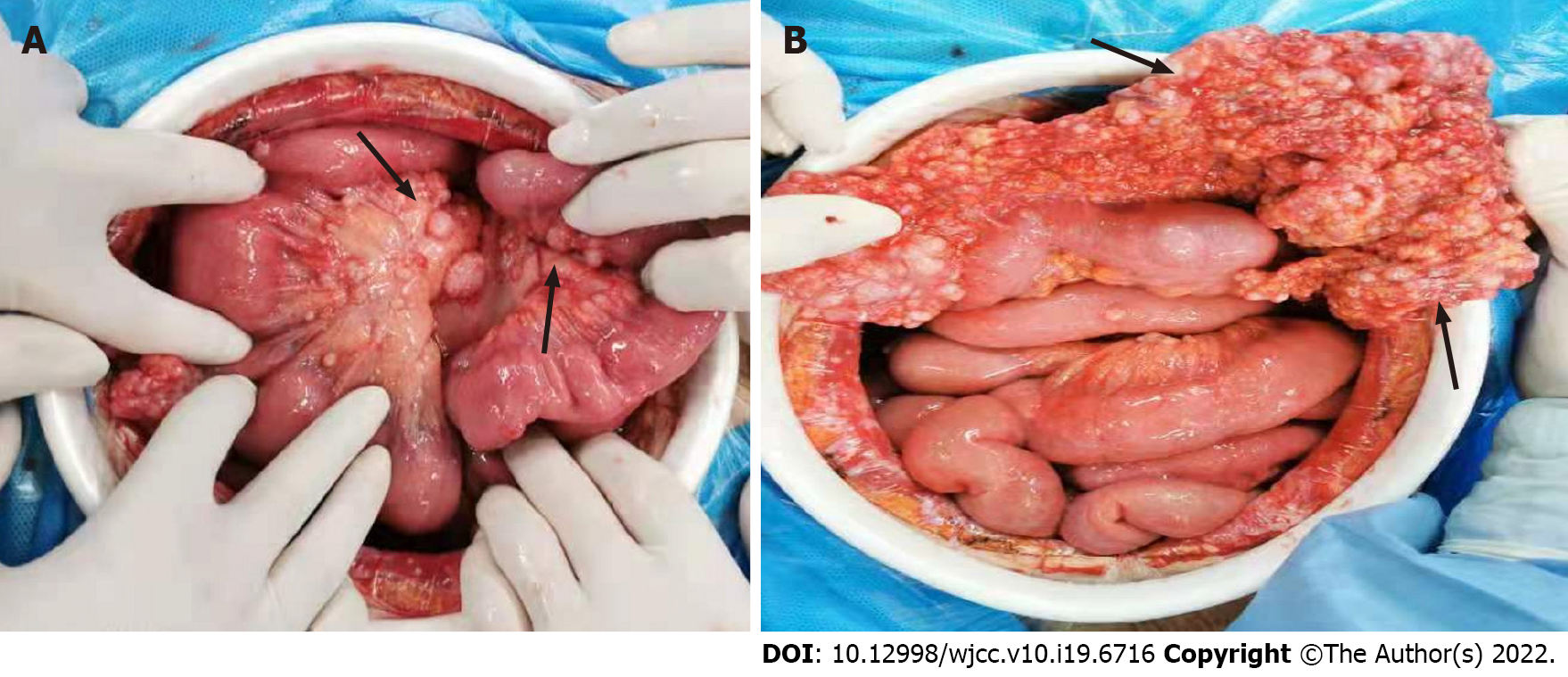

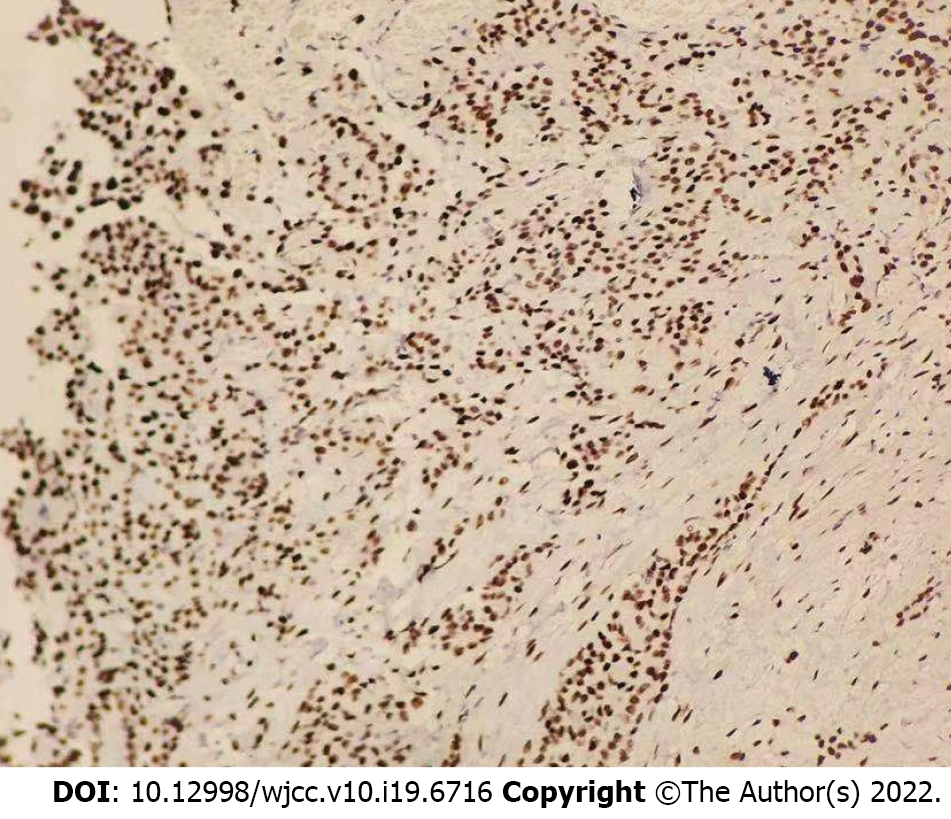

The patient then underwent exploratory laparotomy and a large amount of yellowish ascites was found in the abdominal cavity. There were extensive adhesions between the diaphragm, stomach, spleen and abdominal wall of the liver. Adhesions were severe in most of the small intestine and the mesentery was contracted. The greater omentum was pancake-shaped, multiple round masses were observed in the parietal and visceral peritoneum, with a diameter of 3-20 mm, and the right subphrenic peritoneum was thickened considerably, with an area of approximately 15 cm × 15 cm (Figure 2). Tumors over 3 mm in diameter, the partial right subphrenic peritoneum, and the greater omentum were resected. Pathologic examination showed an epithelioid MPM (Figure 3).

In addition to general comprehensive treatments, the patient was administered pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion after surgery.

At present, the patient has been followed up for 11 mo, and he is in stable condition with no tumor recurrence.

MPM is a malignant tumor originating from mesothelial and subcutaneous cells of the abdominal cavity. Histologically, there are epithelioid, sarcomatoid, and biphasic types of MPM[3]. There is no significant difference in the degree of malignancy among the above types. Elderly men are at high risk for developing MPM. Recently, cases of MPM in young adults have also been reported[4]. MPM is a rare entity and has been linked to industrial pollutants and mineral exposure. There has been an increase in diffusion of chemicals and the incidence of cancer. The most common carcinogen associated with MPM is asbestos, with approximately 80% of cases being associated with asbestos exposure[5,6]. The pathogenesis of MPM is unknown. A BAP1 mutation has been revealed in some patients with MPM by gene analyses, but it was not the only gene involving inherited predisposition to MPM[7]. MPM has insidious onset, and the most common initial symptoms of MPM are abdominal pain, abdominal distension, significant weight loss, ascites, anorexia, and night sweat[8]. Some patients have concurrent paraneoplastic syndromes associated with MPM, such as hypoglycemia, thrombocytosis, venous thrombosis, paraneoplastic liver disease, and wasting syndrome[8]. The diagnosis of MPM is difficult due to its nonspecific and vague symptoms and should be differentiated from alcoholic cirrhosis, as well as liver and pancreatic cancers. Serological tests and tumor markers are of little value, while, there is no specific imaging technique for the detection of MPM. Currently, CT, especially the contrast-enhanced CT, is widely used, with extensive and irregular thickening of the peritoneum, mesentery, and omentum accompanied by massive peritoneal effusion being the typical manifestations of MPM in a CT scan. Positron emission tomography (PET-CT) is valuable in early diagnosis, evaluation of curative effect, and judgment of distant metastasis. The prognosis of patients with MPM is poor. Tumor resection or palliative resection is preferred in the early stage. Pemetrexed combined with cisplatin is a widely accepted chemotherapy for inoperable patients. More clinical trials are needed to investigate the promising treatment of immunotherapy and targeted therapy[9].

In the present case, the patient had a history of long-term alcohol consumption, and the CT scan showed cirrhosis and ascites, which resulted in a diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in the community hospital. After the patient was transferred to our hospital due to poor treatment effect, we performed a contrast-enhanced CT examination and an ascites cytology test, which confirmed the MPM diagnosis. Therefore, a correct diagnosis of rare diseases, including MPM, is always necessary to adjust the treatments plan in a timely manner.

There are some limitations in this report. First, the relationship between alcoholic cirrhosis and MPM remains unknown. Further studies are needed to determine whether there is a correlation between the two diseases. Second, a long-term follow-up remains necessary.

MPM is subjected to misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis because of its insidious onset. Clinicians should be aware of the disease and make a correct diagnosis to provide patients with timely and effective treatment. At the same time, further research on the pathogenesis of the MPM is urgently needed.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Caiati C, Italy; Ferrarese A, Italy; Kumar R, India S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Hernaez R, Hamilton JP. Unexplained ascites. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2016;7:53-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Benzerdjeb N, Dartigues P, Kepenekian V, Valmary-Degano S, Mery E, Averous G, Chevallier A, Laverriere MH, Villa I, Sallé FG, Villeneuve L, Glehen O, Isaac S, Hommell-Fontaine J; RENAPE Network. Combined grade and nuclear grade are prognosis predictors of epithelioid malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a multi-institutional retrospective study. Virchows Arch. 2021;479:927-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ren H, Rassekh SR, Lacson A, Lee CH, Dickson BC, Chung CT, Lee AF. Malignant Mesothelioma With EWSR1-ATF1 Fusion in Two Adolescent Male Patients. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2021;24:570-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim J, Bhagwandin S, Labow DM. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Teta MJ, Mink PJ, Lau E, Sceurman BK, Foster ED. US mesothelioma patterns 1973-2002: indicators of change and insights into background rates. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:525-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Attanoos RL, Churg A, Galateau-Salle F, Gibbs AR, Roggli VL. Malignant Mesothelioma and Its Non-Asbestos Causes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:753-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pagliuca F, Zito Marino F, Morgillo F, Della Corte C, Santini M, Vicidomini G, Guggino G, De Dominicis G, Campione S, Accardo M, Cozzolino I, Franco R. Inherited predisposition to malignant mesothelioma: germline BAP1 mutations and beyond. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:4236-4246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bridda A, Padoan I, Mencarelli R, Frego M. Peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. MedGenMed. 2007;9:32. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Salo SAS, Ilonen I, Laaksonen S, Myllärniemi M, Salo JA, Rantanen T. Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: Treatment Options and Survival. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:839-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |