Published online Jul 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6647

Peer-review started: December 14, 2021

First decision: February 14, 2022

Revised: March 2, 2022

Accepted: April 22, 2022

Article in press: April 22, 2022

Published online: July 6, 2022

Processing time: 191 Days and 13.2 Hours

The overall risk of de novo malignancies in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) is higher than that in the general population. It is associated with long-lasting exposure to immunosuppressive agents and impaired oncological vigilance due to chronic kidney disease. Colorectal cancer (CRC), frequently diagnosed in an advanced stage, is one of the most common malignancies in this cohort and is associated with poor prognosis. Still, because of the scarcity of data concerning adjuvant chemotherapy in this group, there are no clear guidelines for the specific management of the CRCs in KTRs. We present a patient who lost her transplanted kidney shortly after initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer.

A 36-year-old woman with a medical history of kidney transplantation (2005) because of end-stage kidney disease, secondary to chronic glomerular nephritis, and long-term immunosuppression was diagnosed with locally advanced pT4AN1BM0 (clinical stage III) colon adenocarcinoma G2. After right hemicolectomy, the patient was qualified to receive adjuvant chemotherapy that consisted of oxaliplatin, leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX-4). The deterioration of kidney graft function after two cycles caused chemotherapy cessation and initiation of hemodialysis therapy after a few months. Shortly after that, the patient started palliative chemotherapy because of cancer recurrence with intraperitoneal spread.

Initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer increases the risk of rapid kidney graft loss driven also by under-immunosuppression.

Core tip: The occurrence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in kidney transplant recipients is higher than that in the general population. Advanced stage CRC is usually associated with poor outcome. Adjuvant chemotherapy may accelerate the graft loss after kidney transplant.

- Citation: Pośpiech M, Kolonko A, Nieszporek T, Kozak S, Kozaczka A, Karkoszka H, Winder M, Chudek J. Transplanted kidney loss during colorectal cancer chemotherapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(19): 6647-6655

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i19/6647.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i19.6647

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies both in the general population[1] and in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs)[2,3]. The risk of CRC development is reported to be higher in transplant patients because of long-lasting exposure to immunosuppressive agents[4]. Although the patient survival rate for the KTR population with advanced CRC (stage III/IV) at the time of diagnosis is worse, mainly due to higher rates of recurrence, there was no significant difference in a 5-year patient survival in early cancer[5]. CRC in KTRs displays atypical characteristics in terms of tumor location, polyp size, and occurrence. The rate of ascending colon cancer is higher, whereas the rate of rectal cancer is lower in the transplant group[5,6]. Also, the number and size of polyps observed in preo

Here, we present a patient with advanced colon cancer diagnosed 16 years after a successful kidney transplantation, presenting with an irreversible deterioration of kidney graft function shortly after the initiation of adjuvant CTH, to discuss the possible causes of kidney graft loss.

A 36-year-old woman with a medical history of kidney transplantation in 2005, after recent right hemicolectomy due to locally advanced pT4AN1BM0 (clinical stage III) colon adenocarcinoma (G2), was qualified (in March 2021) to adjuvant chemotherapy regimen based on oxaliplatin, leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX-4). At that time, the kidney graft function was satisfactory; however, the slow increase in serum creatinine up to 1.4 mg/dL was observed during the few preceding months. The blood tests showed anemia (hemoglobin, 8.4 g/dL), C-reactive protein 11.2 mg/L, CA-125 18.7 U/mL, and CEA 0.95 ng/mL. After two FOLFOX-4 cycles, substantial deterioration of kidney graft function was observed, resulting in the discontinuation of chemotherapy and return to hemodialysis.

In October 2020 (16 years post-transplant), the patient started to report recurrent mild abdominal pain without concomitant hematochezia, diarrhea, change in bowel motility, or weight loss. At the same time, a slight increase in serum creatinine from 1.0 to 1.4 mg/dL [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 45 mL/min/1.73 m2], with no proteinuria, was detected. In January 2021, the patient was admitted to a surgery department with clinical suspicion of herniation of the terminal ileum into the cecum. During surgery, a large cecal tumor was found (7 cm × 5.5 cm × 5 cm), and a right hemicolectomy with terminal ileum–transverse colon graft was performed. Histological diagnosis was adenocarcinoma G2 invading the peritoneum and blood vessels, with metastases to two of 24 resected mesenteric lymph nodes (pT4AN1B) – corresponding to clinical stage III. A multidisciplinary team qualified the patient to adjuvant chemotherapy (FOLFOX-4), which was suspended due to abdominal wall abscess after the previous surgery. On March 17, 2021 (7 wk since hemicolectomy), the first FOLFOX-4 cycle was administered and the second was on April 1, 2021. However, the subsequent chemotherapy cycles were cancelled due to progressive kidney graft insufficiency. There was no deterioration of blood pressure control during CTH.

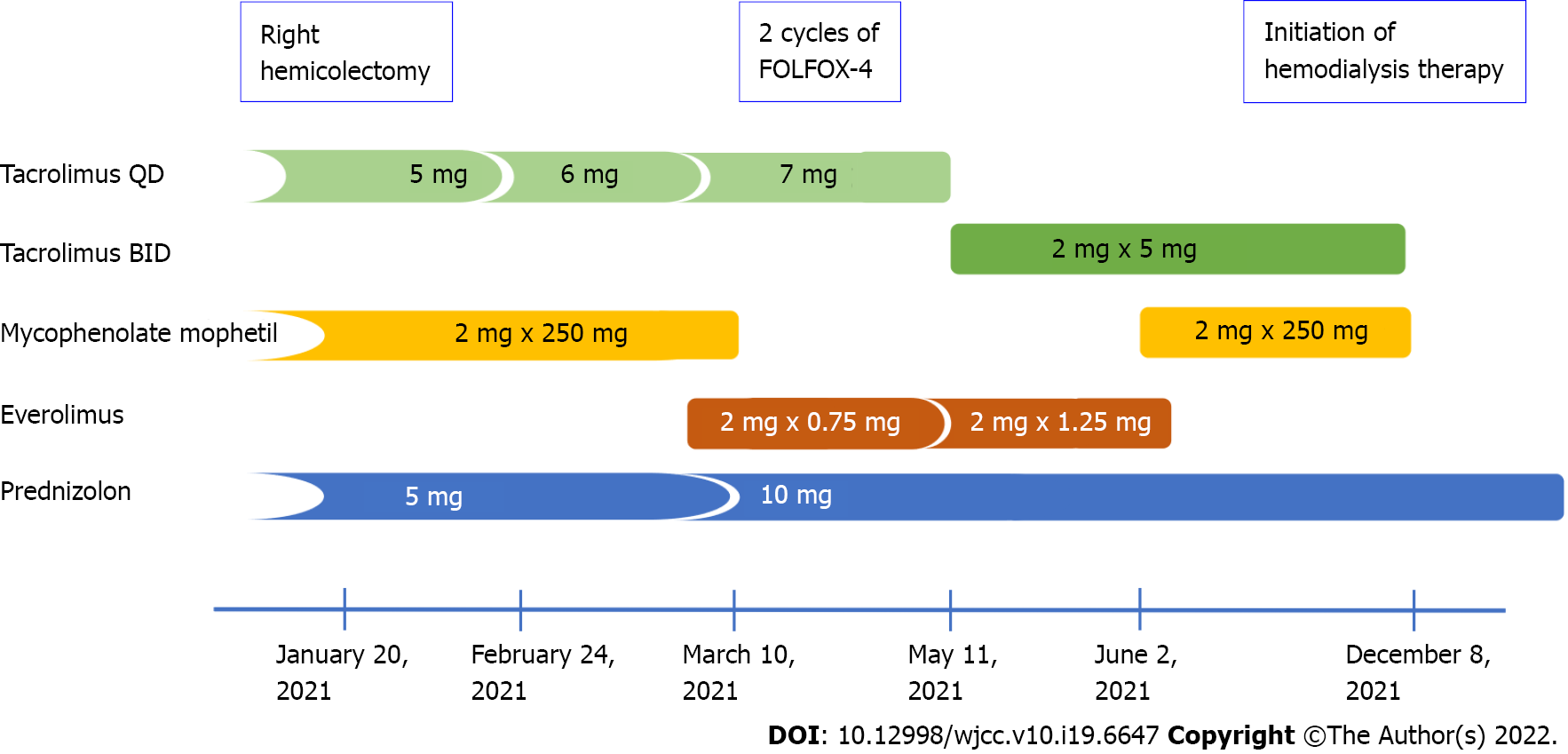

Meanwhile, immunosuppression was modified by conversion from mycophenolate mofetil 250 mg BID to everolimus 0.75 mg BID (Figure 1). Notably, during the subsequent 2 mo, the blood trough levels of everolimus were low (1.0–1.4 ng/mL). Finally, the drug was discontinued because of its poor gastric tolerance. In addition, the tacrolimus level started to fluctuate (with a nadir of 2.5 ng/mL), and de novo proteinuria was noticed up to 4.2 g/24 h. Lately, tacrolimus once daily was switched to twice daily formulation to achieve adequate blood trough levels. Serum creatinine level increased up to 3.4 mg/dL.

The patient was diagnosed with chronic glomerular nephritis at the age of 10 years. It was confirmed by kidney biopsy, and glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide were initiated. In 2001, hepatitis C virus infection was diagnosed, and the patient underwent a successful 12-mo interferon-γ treatment. Hypertension was diagnosed at the age of 18 years in the course of chronic kidney disease. The patient developed end-stage kidney disease and started hemodialysis at the age of 19 years (2004). After 8 mo of dialysis therapy, the patient underwent kidney transplantation (2005) with basiliximab induction. The kidney graft function on an immunosuppressive regimen consisting of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and steroids was excellent, with serum creatinine of 1 mg/dL for many years. The immunosuppression schedule was modified between 4 and 8 years post-transplant by converting mycophenolate to azathioprine due to planned pregnancy. She passed two pregnancies, giving birth during 5 and 8 years post-transplant. During the whole observation, there were no episodes of acute kidney rejection or proteinuria. The blood trough levels of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were stable, at 6–7 ng/mL and 2.7 ng/mL, respectively.

Family history was unremarkable.

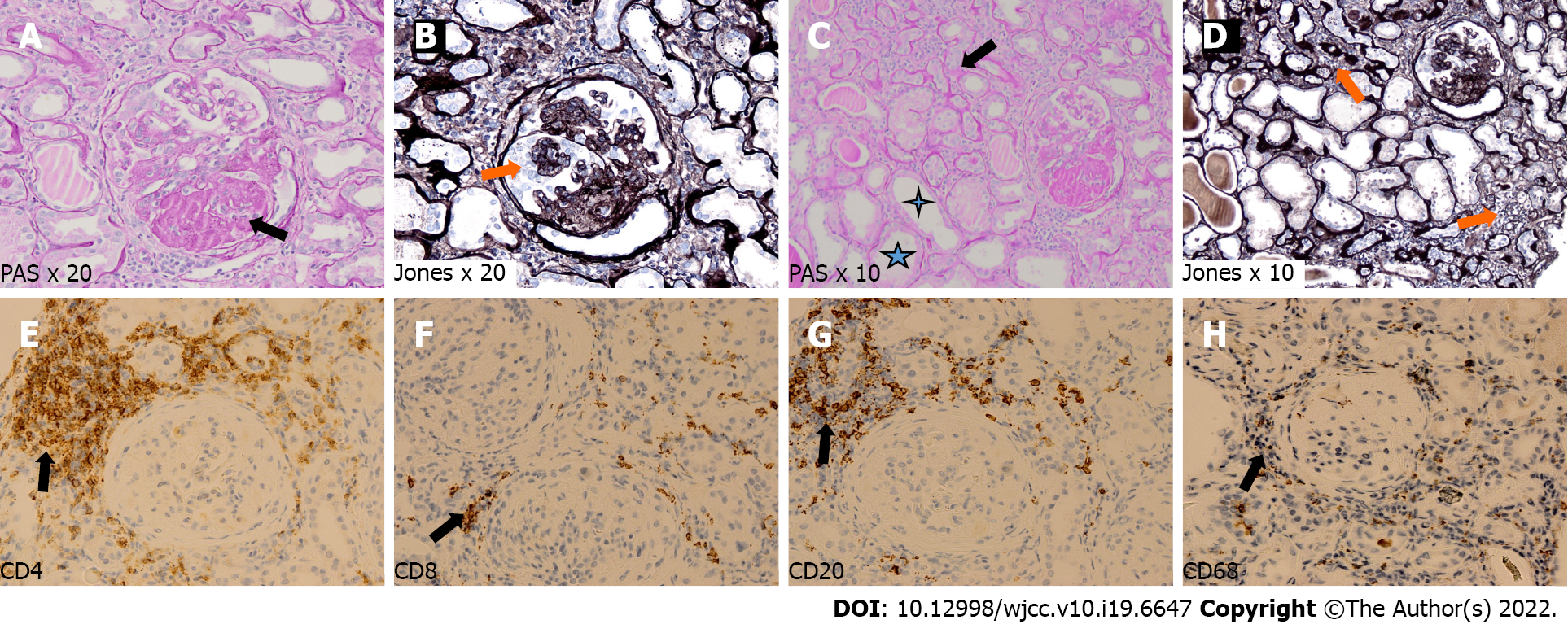

Physical examination revealed no abnormalities except surgical scars.

Because of the increase of serum creatinine up to 3.4 mg/dL, a kidney graft biopsy was performed on June 1, 2021. Histological examination revealed overlapping features of active chronic rejection and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Overall, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy covered > 50% of the interstitial area (Figure 2). Donor-specific antigens were not present, whereas a moderate Epstein–Barr viremia (7485 copies/mL) was detected. Other virological results (hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and cytomegalovirus) were negative at that time.

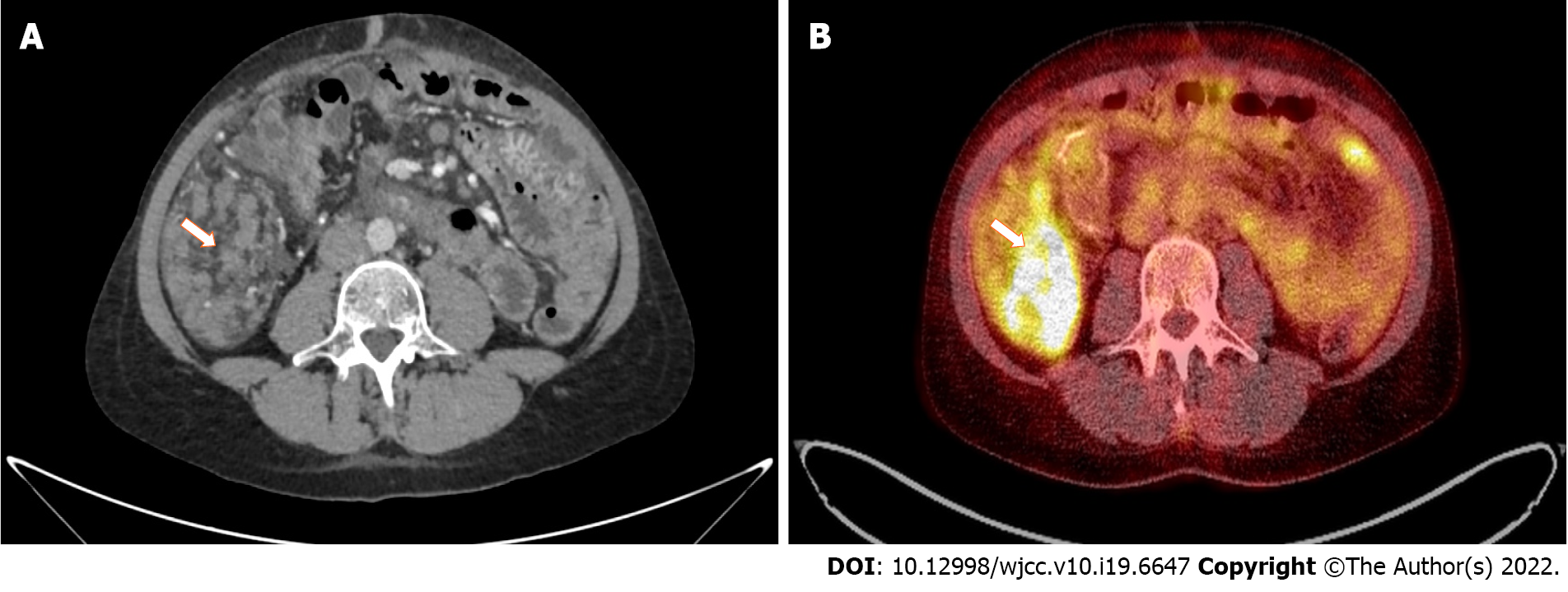

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast media administration was performed twice, during the oncological work-up, in June and September 2021. The second examination visualized intraperitoneal spread of colon adenocarcinoma, confirmed by positron emission tomography/CT (Figure 3), and corresponding with recent patient complaints about abdominal pain.

Active chronic rejection of transplanted kidney with features of recurrent glomerulonephritis and further intraperitoneal spread of colon cancer was also diagnosed.

Hemodialysis therapy was initiated after creating an arteriovenous shunt when serum creatinine level exceeded 6 mg/dL. Before initiation of palliative chemotherapy, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF genotyping was performed. The analysis revealed mutation in codon 12 of the second exon (35 G>T) of KRAS, denoting resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy. FOLFOX-4 regimen was chosen as the first-line palliative chemotherapy due to early discontinuation of this regimen in the adjuvant setting, frequent intestinal toxicity of irinotecan in hemodialysis patients, and restriction in the reimbursement of bevacizumab in patients with chronic kidney disease.

The patient remains under the care of an oncologist and nephrologist, continuing hemodialysis and palliative chemotherapy. The timeline of the information presented in this case report is shown in Table 1.

| Date | Procedure |

| 1994 | Diagnosis of glomerular nephritis (kidney biopsy) |

| 1994 | Therapy with glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide |

| 2004 | Initiation of hemodialysis therapy |

| 2005 | Kidney transplantation |

| October 2020 | Recurrent abdominal pain |

| January 26, 2021 | Right hemicolectomy |

| February 2021 | Initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy (FOLFOX-4) |

| February 25, 2021 | Abdominal laceration abscess surgery |

| March 17 to 19, 2021 | 1st FOLFOX-4 |

| April 1, 2021 | 2nd FOLFOX-4 |

| April 19, 2021 | Postponement of chemotherapy |

| May 5, 2021 | Postponement of chemotherapy |

| May 14, 2021 | Adjuvant chemotherapy termination |

| June 1, 2021 | Kidney graft biopsy |

| June 17, 2021 | First CT of the abdomen and pelvis |

| September 30, 2021 | Second CT of the abdomen and pelvis |

| October 28, 2021 | Surgical creation of an arteriovenous shunt |

| October 29, 2021 | PET-CT |

| December 8, 2021 | Initiation of hemodialysis therapy |

| December 21, 2021 | Initiation of palliative chemotherapy (FOLFOX-4) |

Cancer is the second most common cause of mortality and morbidity in KTRs after cardiovascular disease[7]. This increased cancer risk in the KTR population is driven mainly by de novo cancers, with CRC being the third most common cause of cancer death after non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and lung cancer[8]. CRC in KTRs is reported to have a worse 5-year survival rate than in the general population[9,10], and develops more often at a younger age[9-11]. Even so, our patient was diagnosed with an advanced CRC at the age of 36 years. However, an analysis of Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry Data revealed that cancer rates in KTRs are similar to those in nontransplanted subjects 20–30 years older[12]. Still, it is noteworthy that there were some additional risk factors for such an early development of cancer in the given patient, except for the post-transplant immunosuppression. Firstly, the primary kidney disease was glomerulonephritis treated with steroids and cyclophosphamide, whereas the pretransplant immunosuppressive treatment was shown to increase the cancer risk[12,13]. Secondly, the use of azathioprine could be an independent risk factor for advanced colorectal neoplasia in KTRs[14]. The patient has received this medication for 5 years because of the planned conception. Thirdly, unlike the virus-related malignancies such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and cervical cancer, CRC used to develop late in the post-transplant observation[3], as in our case.

Nevertheless, when considering the undisputed tendency to the CRC development in younger KTRs in comparison to the general population, modified screening strategies were suggested in this specific cohort, including increased colonoscopy frequency[9] and early initial post-transplant colonoscopy within 2 years[10]. To date, KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) Guidelines suggested that screening for CRC should be performed as recommended for the general population[15]. A cost–benefit ratio is another issue, as it was shown that eight colonoscopies were needed to identify one case of advanced neoplasia in KTRs cohort older than 50 years[16]. Although some authors suggested that screening colonoscopy in KTRs should be expanded to include recipients younger than 50 years[11] or even between the age of 35 and 50 years[17], such a policy would be cost-ineffective, in contrast to a screening program with fecal hemoglobin testing[17]. However, the latter measure is characterized by poor sensitivity but reasonable specificity. Besides, a fecal hemoglobin concentration can be used to stratify probability for the detection of advanced colorectal neoplasia in individuals with positive fecal immunochemical test[18].

In KTRs diagnosed with cancer, treatment includes conventional approaches based on surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy[7]. Such a complex treatment, often complicated by adverse reactions, is effective, even in advanced CRC cases[19]. Although the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy is a current standard of care in stage III colon cancer, the complication risk of such therapy is strongly recommended to be assessed, especially among patients with pre-existing kidney dysfunction[1]. The data concerning adjuvant and palliative chemotherapy and their outcomes in KTRs are limited (Table 2). Some advanced stage transplant patients did not receive adequate chemotherapy because of the concern of drug–drug interactions with the immunosuppressive regimen[20]. Despite that oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil are partly excreted in urine, the renal toxicity potential of anti-CRC drugs is low, except for de novo proteinuria and arterial thromboembolic events observed during bevacizumab therapy[20]. Nevertheless, oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy is neither nephrotoxic[21] nor interferes with blood levels of immunosuppressants[20]. However, it has been reported that repeated cycles of oxaliplatin in patients with prior renal impairment may cause deterioration of kidney function[22]. In our case, the kidney graft function before FOLFOX-4 initiation was already impaired (eGFR 45 mL/min/1.73 m2), but it rapidly deteriorated during the first 2 mo of therapy. However, it might have been caused by active chronic rejection coexisting with recurrent glomerulonephritis, which probably started earlier, as indicated by the previously slowly increasing serum creatinine concentration. Moreover, both processes mentioned above might be accelerated by decreasing net immunosuppression strength caused by modification of the immunosuppressive regimen and impaired drug absorption after hemicolectomy. Nevertheless, although reducing immunosuppression treatment with or without conversion to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor is suggested in KDIGO guidelines[15] and the literature[7,23], the risk of graft rejection and loss is not to be disregarded.

| Refs | Patients | Sex | Age at diagnosis, yr | Clinical stage | Chemotherapy | Cycles | Graft loss | ADR | Response | DFS/PFS (mo) | OS (mo) |

| Kim et al[5] | 5 of 171 | 6 W, 11 M | 54 ± 7 | Stage 0 (n = 2) | Yes, 2 (within 1 yr) | 25.1 ± 9.2 | |||||

| Stage I (n = 5) | |||||||||||

| Stage II (n = 3) | FU-LV (n = 1) | 12 | NS | NA | |||||||

| Stage III (n = 3) | Capecitabine (n = 2) | 12 | NS | 25 | |||||||

| Stage IV (n = 4) | Capecitabine (n = 1); FU-LV (n = 1) | 812 | NS | 10 | |||||||

| Fang[20] | 1 | M | 36 | Stage II (pT3N0M0) | FOLFOX | 3 | No | NS | PD | 0 | NA |

| Liu et al[24] | 2 | M | 44 | Stage II (pT3N0M0) | Capecitabine | 8 | No | NA | SD | NA | Alive after 21 |

| M | 54 | Stage II (pT3N0M0) | Capecitabine | 8 | No | NA | SD | NA | Alive after 8 | ||

| Xia et al[25] | 1 | M | 51 | Stage III B (pT3N1M0) | FOLFOX | 8 | No | NS | PR | NA | NA |

| Liu et al[24] | 1 | M | 68 | Stage III (pT4N1M0) | Capecitabine (after progression) | 3 | No | NS | PR | 2 | 4-5 for CTH |

| Müsri et al[26] | 1 | M | 64 | Stage IV | FOLFIRI + bevacizumab | 5 | NS | Proteinuria | PR (regression of liver metastasis) | NA | NA |

| Deterioration of kidney function | |||||||||||

| Bellyei et al[19] | 1 | M | 66 | Stage IV | FOLFIRI + cetuximab | 1 | No | Blood sugar level fluctuation | NA | NA | NA |

| Diarrhea | |||||||||||

| Hypomagnesemia | |||||||||||

| FOLFIRI + panitumumab | 3 | No | Weight loss | PR(paraaortic lymph node regression) | NA | NA | |||||

| Diarrhea | |||||||||||

| Hypomagnesemia | |||||||||||

| SBRT + panitumumab | 16 | No | Skin rash | CR | NA | NA-stroke | |||||

| Hypomagnesemia |

Several risk factors, including long-lasting immunosuppression, may contribute to CRC development in KTRs at a younger age. We acknowledge the risk of rapid kidney graft loss, which occurred during the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer, but it may rather be a consequence of under-immunosuppression due to both impaired drug absorption and treatment changes driven by the cancer diagnosis. Hence, any modification of immunosuppressive regimen in newly diagnosed cancer patients should be carefully considered to balance the potential risks and benefits, bearing in mind the kidney graft function.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Poland

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gadelkareem RA, Egypt; Kaewput W, Thailand; Kiuchi J, Japan; Singh N, United States S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Argilés G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, Hochhauser D, Salazar R, Iveson T, Laurent-Puig P, Quirke P, Yoshino T, Taieb J, Martinelli E, Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1291-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 806] [Article Influence: 161.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pendón-Ruiz de Mier V, Navarro Cabello MD, Martínez Vaquera S, Lopez-Andreu M, Aguera Morales ML, Rodriguez-Benot A, Aljama Garcia P. Incidence and Long-Term Prognosis of Cancer After Kidney Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:2618-2621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ju MK, Joo DJ, Kim SJ, Huh KH, Kim MS, Jeon KO, Kim HJ, Kim SI, Kim YS. Chronologically different incidences of post-transplant malignancies in renal transplant recipients: single center experience. Transpl Int. 2009;22:644-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Andrés A. Cancer incidence after immunosuppressive treatment following kidney transplantation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;56:71-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim JY, Ju MK, Kim MS, Kim NK, Sohn SK, Kim SI, Kim YS. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of colorectal cancer in renal transplant recipients in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:454-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Merchea A, Abdelsattar ZM, Taner T, Dean PG, Colibaseanu DT, Larson DW, Dozois EJ. Outcomes of colorectal cancer arising in solid organ transplant recipients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:599-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Au E, Wong G, Chapman JR. Cancer in kidney transplant recipients. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:508-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Au EH, Chapman JR, Craig JC, Lim WH, Teixeira-Pinto A, Ullah S, McDonald S, Wong G. Overall and Site-Specific Cancer Mortality in Patients on Dialysis and after Kidney Transplant. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Papaconstantinou HT, Sklow B, Hanaway MJ, Gross TG, Beebe TM, Trofe J, Alloway RR, Woodle ES, Buell JF. Characteristics and survival patterns of solid organ transplant patients developing de novo colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1898-1903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Johnson EE, Leverson GE, Pirsch JD, Heise CP. A 30-year analysis of colorectal adenocarcinoma in transplant recipients and proposal for altered screening. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:272-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Privitera F, Gioco R, Civit AI, Corona D, Cremona S, Puzzo L, Costa S, Trama G, Mauceri F, Cardella A, Sangiorgio G, Nania R, Veroux P, Veroux M. Colorectal Cancer after Kidney Transplantation: A Screening Colonoscopy Case-Control Study. Biomedicines. 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Webster AC, Craig JC, Simpson JM, Jones MP, Chapman JR. Identifying high risk groups and quantifying absolute risk of cancer after kidney transplantation: a cohort study of 15,183 recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2140-2151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hibberd AD, Trevillian PR, Wlodarczyk JH, Kemp DG, Stein AM, Gillies AH, Heer MK, Sheil AG. Effect of immunosuppression for primary renal disease on the risk of cancer in subsequent renal transplantation: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2013;95:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Au EH, Wong G, Howard K, Chapman JR, Castells A, Roger SD, Bourke MJ, Macaskill P, Turner R, Lim WH, Lok CE, Diekmann F, Cross N, Sen S, Allen RD, Chadban SJ, Pollock CA, Tong A, Teixeira-Pinto A, Yang JY, Kieu A, James L, Craig JC. Factors Associated With Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia in Patients With CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79:549-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9 Suppl 3:S1-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 1098] [Article Influence: 68.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Collins MG, Teo E, Cole SR, Chan CY, McDonald SP, Russ GR, Young GP, Bampton PA, Coates PT. Screening for colorectal cancer and advanced colorectal neoplasia in kidney transplant recipients: cross sectional prevalence and diagnostic accuracy study of faecal immunochemical testing for haemoglobin and colonoscopy. BMJ. 2012;345:e4657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wong G, Howard K, Craig JC, Chapman JR. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2008;85:532-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Auge JM, Pellise M, Escudero JM, Hernandez C, Andreu M, Grau J, Buron A, López-Cerón M, Bessa X, Serradesanferm A, Piracés M, Macià F, Guayta R, Filella X, Molina R, Jimenez W, Castells A; PROCOLON Group. Risk stratification for advanced colorectal neoplasia according to fecal hemoglobin concentration in a colorectal cancer screening program. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:628-636.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bellyei S, Boronkai Á, Pozsgai E, Fodor D, Mangel L. Effective chemotherapy and targeted therapy supplemented with stereotactic radiotherapy of a patient with metastatic colon cancer following renal transplantation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15:125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fang W. Chemotherapy in patient with colon cancer after renal transplantation: A case report with literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Haller DG. Safety of oxaliplatin in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2000;14:15-20. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kawazoe H, Kawazoe H, Sugishita H, Watanabe S, Tanaka A, Morioka J, Suemaru K, Watanabe Y, Kawachi K, Araki H. [Nephrotoxicity induced by repeated cycles of oxaliplatin in a Japanese colorectal cancer patient with moderate renal impairment]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37:1153-1157. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Alberú J. Clinical insights for cancer outcomes in renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:S36-S40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Liu HY, Liang XB, Li YP, Feng Y, Liu DB, Wang WD. Treatment of advanced rectal cancer after renal transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2058-2060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xia Z, Chen W, Yao R, Lin G, Qiu H. Laparoscopic assisted low anterior resection for advanced rectal cancer in a kidney transplant recipient: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Müsri FY, Mutlu H, Eryılmaz MK, Salim DK, Coşkun HŞ. Experience of bevacizumab in a patient with colorectal cancer after renal transplantation. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:1018-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |