Published online Jun 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6261

Peer-review started: December 17, 2021

First decision: January 26, 2022

Revised: February 8, 2022

Accepted: April 21, 2022

Article in press: April 21, 2022

Published online: June 26, 2022

Processing time: 181 Days and 20.7 Hours

Type Ⅲb dens invaginatus (DI) with a lateral canal located at the mid-third of the root is rarely reported. Here, we report a rare case of type Ⅲb DI in the left upper anterior tooth with a lateral canal that led to persistent periodontitis.

A 15-year-old female patient presented with a chief complaint of pain associated with recurrent labial swelling in the area of the left anterior tooth. A diagnosis of type Ⅲb DI and chronic periodontitis was made. Intentional replantation was performed after conventional endodontic treatment failed. After 6 mo, the patient was asymptomatic, but a sinus tract was observed. Cone-beam computed tomo

Type Ⅲb DI with a lateral canal can be successfully treated by root canal treatment, intentional replantation, and surgical therapy.

Core Tip: Type Ⅲb dens invaginatus (DI) with a lateral canal located at the mid-third of the root is first reported. Here, we report a rare case of type Ⅲb DI in the left upper anterior tooth with a lateral canal that led to persistent periodontitis and it was successfully treated by a combination of root canal treatment, intentional replantation, and surgical therapy.

- Citation: Zhang J, Li N, Li WL, Zheng XY, Li S. Management of type IIIb dens invaginatus using a combination of root canal treatment, intentional replantation, and surgical therapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(18): 6261-6268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i18/6261.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6261

Dens invaginatus (DI) is a dental developmental anomaly resulting from enamel enfolding into the dental papilla prior to calcification. DI occurs more often in permanent maxillary lateral incisors and less frequently in mandibular anterior and deciduous teeth[1]. Clinically, pits lined with enamel defects and dentin invaginated into the dental/teeth with DI are susceptible to caries due to microorganism accumulation, easily leading to pulp necrosis and periapical inflammation[2]. However, DI may be easily overlooked due to the absence of clinical signs of malformation.

The most widely known classification of DI into three types was made by Oehler[3] in 1957 based on the extent of invagination from the crown into the root. Type III is the most complicated form due to the more extreme anatomical complexity. Type Ⅲa refers to invagination penetrating through the root and forming a lateral foramen as a pseudoforamen, while type Ⅲb refers to invagination extending through the root with an apical foramen. There is usually no communication with the pulp, which lies compressed within the wall around the invagination process. However, to our knowledge, this is the first report of a tooth of type IIIb DI infected via a lateral canal.

DI poses a great challenge in endodontic treatment due to the development of malformations with distortion of the teeth. Canal irregularities and invagination may prevent mechanical and chemical preparation. Due to the anatomic variations of the complex root canal morphologies, various treatment options have been proposed, including sealing of the invagination, root canal treatment, intentional replantation, periapical microsurgery, and extraction[4-6]. Here, we report a complex case of type Ⅲb DI with a lateral canal. After endodontic treatment, intentional replantation, and periapical microsurgery, the clinical findings and radiographic assessment presented a favorable prognosis of effective periapical healing at a 3-year follow-up assessment.

A 15-year-old female patient presented to the Department of Endodontics, Anhui Medical University, China with a chief complaint of pain associated with recurrent labial swelling in the area of the left anterior tooth for the past 6 mo. The patient reported that she had undergone endodontic treatment 1 mo earlier with symptom recurrence.

The patient presented to the Department of Endodontics, Anhui Medical University, China, with a chief complaint of pain associated with recurrent labial swelling in the area of the left anterior tooth for the past 6 mo.

The patient reported that she had undergone endodontic treatment 1 mo earlier with symptom recurrence.

The patient had a noncontributory personal and family history.

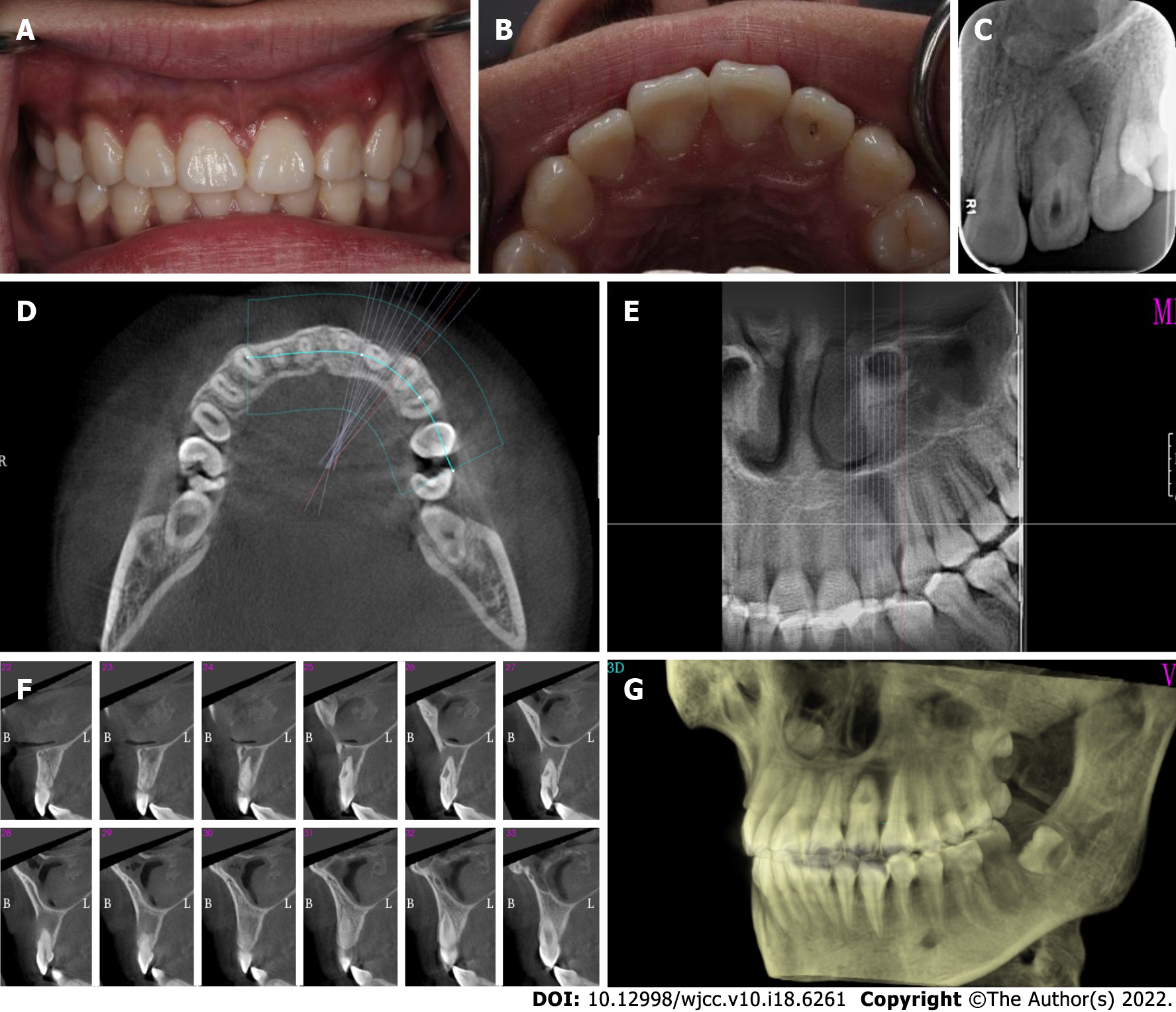

Oral examination revealed fluctuating buccal swelling with a sinus at the apical area (Figure 1A). Tooth 22 showed an intact crown with a palatal access cavity (Figure 1B). Sensitivity to vertical percussion and negativity to palpation and electric pulp testing were observed, whereas the response of adjacent teeth was normal. The periodontal probing depths were within the normal range with slight mobility. Radiography showed an invagination of dentin lined by enamel into the pulpal space, expanded space in the middle of the teeth with a large periapical radiolucent lesion, and the presence of bone resorption (Figure 1C).

The patient's blood test results were all normal.

A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan showed invagination extending from the crown into the root with an apical foramen associated with a large periapical radiolucent lesion, which caused variation in the main root canal. A well-defined unilocular periapical radiolucent lesion was observed. Sagittal CBCT images showed that a loop-shaped chamber separated the main root canal (Figure 1D-G).

A diagnosis of type Ⅲb DI and chronic periodontitis was made.

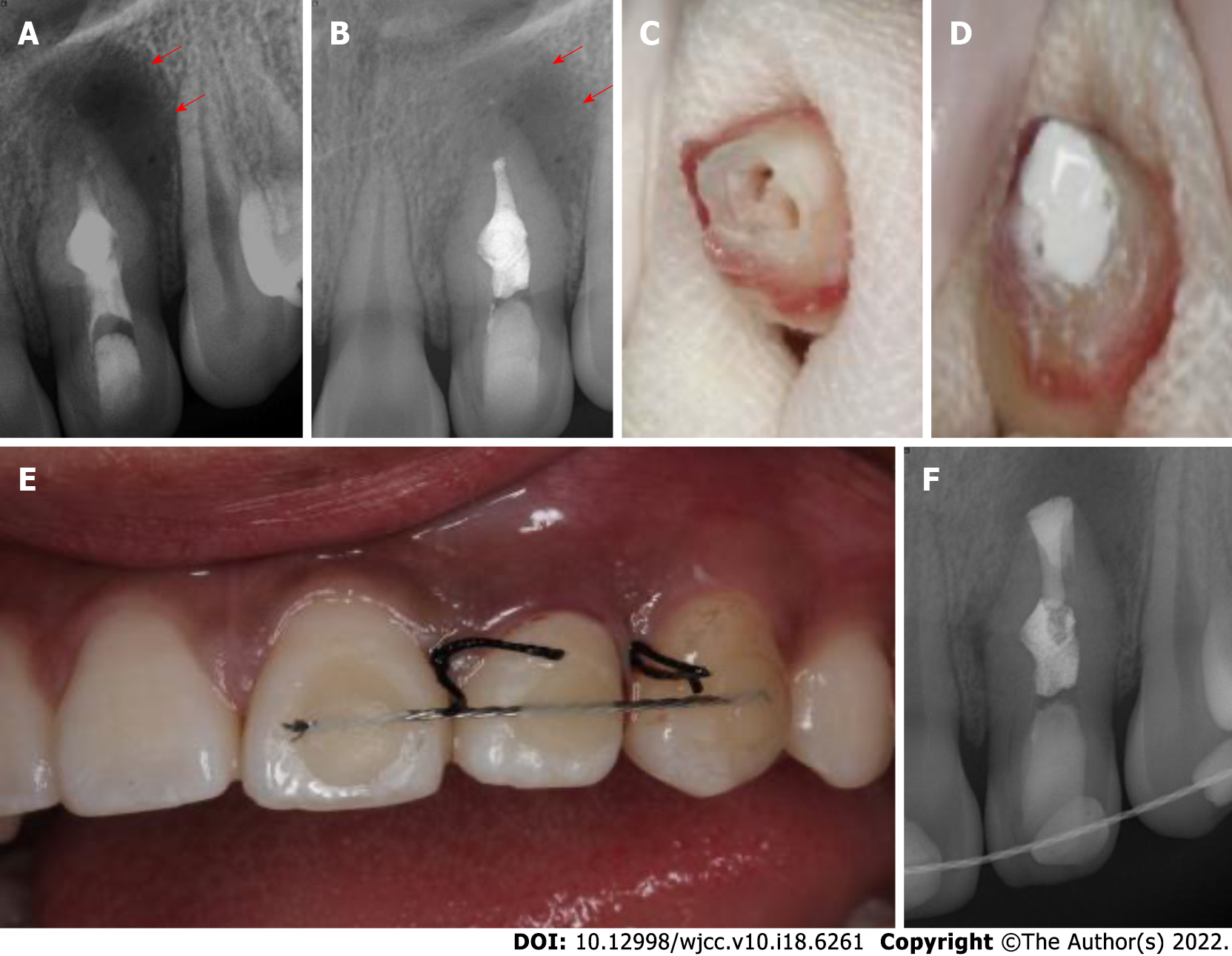

Under rubber dam isolation, the temporary filling was removed, and access to the main and invaginated canals was completed. Pulp vitality in the main canal and dens invaginatus canal confirmed necrosis. The total length of the canals was estimated to be 19 mm, and the canals were then thoroughly prepared to apical size 30 by the crown-down technique with a NiTi file. A large volume of pale-yellowish fluid drained from the canal. Following thorough irrigation with 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), the root canals were dried with paper points, and calcium hydroxide paste was placed into the two canals (Figure 2A). The coronal access was sealed with a 3-mm-thick temporary restorative material. The patient was scheduled to return after 2 wk.

As endodontic therapy failed and the aberrant anatomic structure hampered adequate disinfection and obturation, the patient was informed that root canal retreatment could not clean out the infected pulp tissue clearly and obturation could not seal the pseudo canal tightly. Intentional replantation and surgical treatment were chosen as the next treatment. After discussing the risk and the financial cost, her parents chose to perform intentional replantation at the 2-wk follow-up appointment (Figure 2B). The patient received 500 mg amoxicillin and 400 mg ibuprofen 30 min before surgery and was instructed to rinse with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate solution. After local anesthesia, a minimal portion of tooth 22 was extracted without any fracture. The crown was held by saline-soaked wet gauze to keep the teeth moist and to minimize damage to the periodontal ligament (PDL) (Figure 2C). Under the dental operating microscope, the apex of the tooth was resected with a high-speed handpiece for 3 mm, and the foramen was clearly and deeply prepared by ultrasonic tips. iBoot BP (Innovative BioCeramix Inc., Vancouver, Canada) was placed to completely seal the retrograde cavity (Figure 2D). Then, the tooth was gently replanted into the socket and fixed by a wire and composite resin splint (Figure 2E). The extraoral times were limited to under 13 min. A radiograph was taken to confirm that the depth of iBoot BP was approximately 5 mm (Figure 2F). After the surgery was performed, amoxicillin (500 mg, 3 times per day) was administered for 3 d to prevent wound infection. The patient was instructed to maintain a soft diet and use a 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse for 2 wk.

Two weeks after the procedure, the patient returned, and the wire and composite resin splint were removed. After removal of the temporary restorative material under rubber dam isolation, calcium hydroxide paste in the root canals was cleared by ultrasonication. After drying the canals with paper points, the canals were fully obturated with gutta percha, and iRoot BP (Innovative BioCeramix Inc.) was performed using a vertical condensation technique. Subsequently, tooth 22 was restored using acid-etch and composite resin Z350 (3M ESPE, MN, United States).

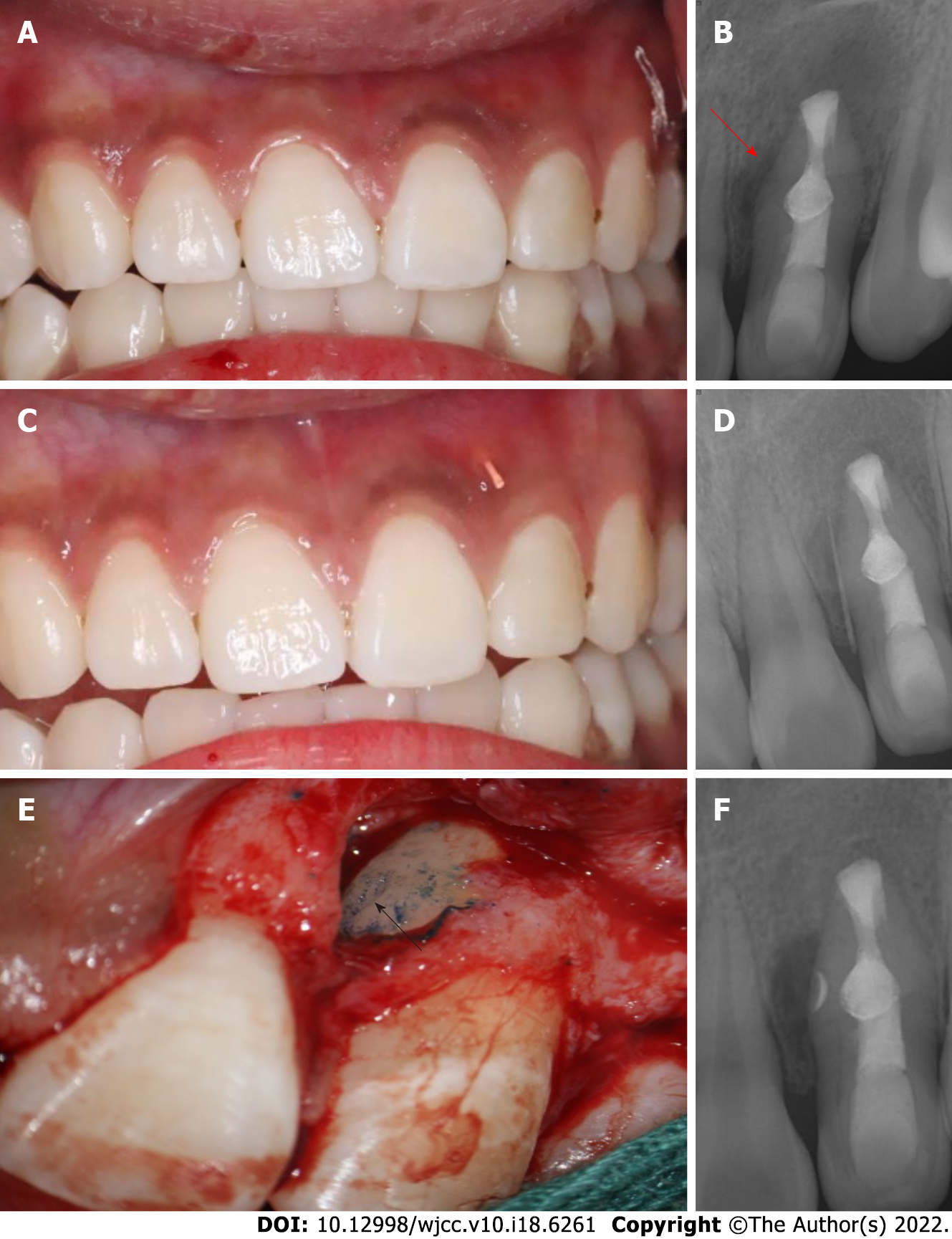

Unfortunately, 6 mo later, the patient returned pain-free, but the swelling (sinus tract) in the buccal maxillary region reappeared (Figure 3A and B). A gutta percha point in the draining sinus revealed point tracking to a large periapical lesion associated with the mesial surface of tooth 22 (Figure 3C and D).

The patient refused the extraction and had a strong desire to preserve natural tooth 22. The patient and her parents agreed to perform endodontic microsurgery as a last resort to seal the lateral canal in the mesial of tooth 22. After local anesthesia, a full-thickness triangular mucoperiosteal flap was made to expose the mesial area of tooth 22. The root surface was stained with methylene blue to identify the lateral foramen. An L-shaped pit on the mid-root surface was observed, which was then prepared with an ultrasonic tip and obturated with iRoot BP (Figure 3E and F). The granulomatous tissues were curetted, and the surgical region was irrigated with 0.9% saline. Finally, the flap was repositioned and sutured. The sutures were removed after 2 wk.

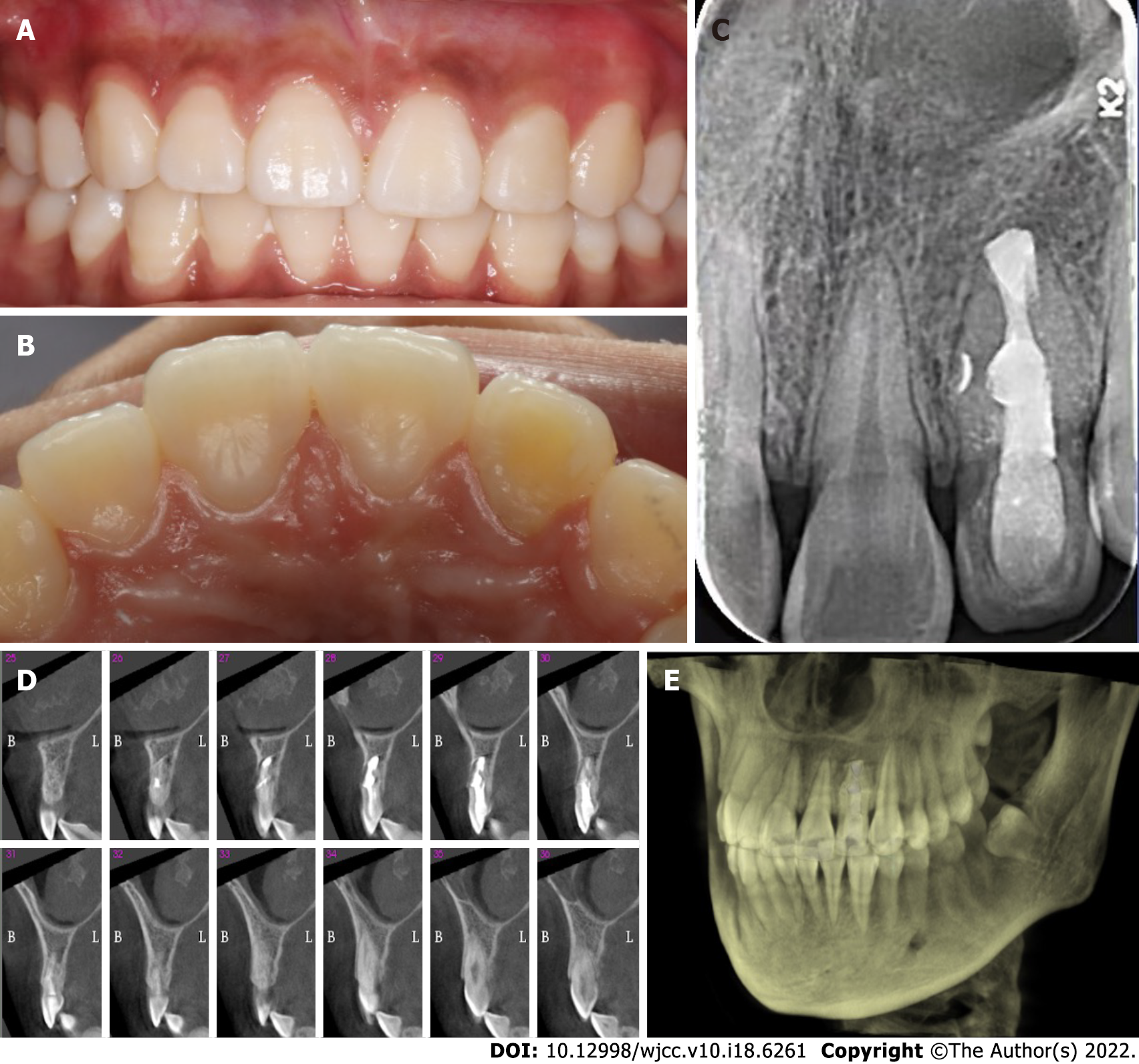

At the 3-year recall evaluation, the patient had no painful symptoms. The radiograph image presented complete healing of the periapical lesion around the tooth root. Continuity of the periodontal ligament was observed, and intercortical bone had formed completely without any root resorption or ankylosis (Figure 4).

Treatment for DI varies depending on the invagination type, anatomy of the canal, level of pulp involvement, and morphology of the apex. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an infection of type IIIb DI with a lateral canal resulting in the persistence of periapical damage. Microorganism contamination in the invagination easily inflames the pulp irreversibly and even causes pulp necrosis both in the main canal and the invagination canal, especially in patients with type III DI. In patients with type IIIa DI, endodontic treatment should be performed on the canals as if they were two independent canals[6]. In patients with type IIIb, some authors recommend removing the extremely large anomalous invagination using ultrasonic instruments and combining the two canals as one space to allow for complete and sufficient disinfection[7]. The removal of the single and large canal was followed by obturation with mineral trioxide aggregate in the apical third. However, the elimination of invagination severely compromised the strength of the tooth and increased the risk of tooth fracture. Martins et al[7] reported that three Fibercore posts were applied to the root canal to reinforce the thin root wall. In this reported case, the invaginated cavity occupied the center of the canal and adhered labially to the canal wall. Removal of the invaginated hard tissue was impractical. Such removal would cause a thin outer shell of dentine to remain, which may result in a poor prognosis.

Successful root canal treatment is based on the complete removal of all infections in the entire root canal system[8]. However, due to the anatomical impediments of type IIIb DI that restrict instrument cleaning and sufficient shaping, chemomechanical preparation cannot effectively eliminate all the infected tissues in the main canal or the invagination canal, including lateral canals and apical ramifications[9]. This would cause root canal treatment to occasionally fail, resulting in the persistence of periapical damage. Since a conventional root canal, as the first alternative, had already been initiated and failed in this patient, surgical endodontic or intentional replantation was the second treatment option instead of tooth extraction[10].

Intentional replantation is defined as deliberate extraction of the teeth and visual endodontic manipulation followed by reinsertion back into the original socket. The advantages of intentional replantation are that the major procedure is performed visually and that it benefits inaccessible areas, including the morphological variation in type IIIb DI[11]. A recent systematic review demonstrated that the survival rate of intentional replantation was 90%[12]. In a retrospective study of ten cases of type IIIb DI with apical periodontitis treated by intentional replantation, the survival rate was 80%[13]. Due to its high survival rate, low invasiveness, and cost-effectiveness, intentional replantation is regarded as a reliable and viable treatment when root canal treatment fails. PDL is important for the success of intentional replantation. Yu et al[14] reported that PDL cells remained alive within 15 to 20 min, which was crucial for the ability of PDL cells to attach to the alveolus. In this patient, we limited the extraoral time to 13 min, leading to successful periradicular healing.

Unfortunately, the sinus tract in the buccal maxillary region was noted at six recall evaluations. In the initial radiograph, we focused on the morphological variation of DI and periapical infection while ignoring the lateral infection caused by organisms in the lateral canal. Considering the patient’s wishes and with the aid of methylene blue staining, surgical treatment was attempted as the last resort to obturate the lateral canal. Lateral canals are accessory canals that usually extend vertically to the main canal. They are not easily visible in preoperative radiographs[9]. Ricucci et al[9] assessed 500 representative extracted teeth that were scanned by microcomputed tomography. The authors found that lateral canals occurred more frequently in the apical third of the root than in the middle of the root. The shape and tortuosity of the lateral canals may vary among different teeth. Most of the lateral canals were curved and not circular, as reported in this patient, which increased the complexity of the treatment. The median diameter of the lateral canals is 67 µm, while the diameter of the main canals is two to three times larger[15,16]. Therefore, apical periodontitis occurs far more frequently than lateral periodontitis.

Some studies have reported that periradicular inflammation has no relationship with unfilled lateral canals[17], and some authors have argued that an insufficiently obturated lateral canal can lead to endodontic treatment failure. This was attributed to the patency of the lateral canal and microbiological involvement[18]. Kim and Kratchman[19] recommended resecting at least 3 mm of apical root to eliminate 98% of apical ramifications and 93% of lateral canals that exist within 3 mm of the root end. However, in this patient, the foramen of the later canal was located at the middle third of the root. Therefore, removal of 3 mm of root end by surgical treatment would not have benefited lateral periodontitis healing. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a tooth of type IIIb DI infected via the lateral canal located at the middle of the root.

Type IIIb DI has a variety of atypical internal morphologic complexities, which presents a great challenge for treatment in the clinic. This reported case highlights the significance of awareness of type IIIb DI with a lateral canal in the middle of the root. This result indicated that complex type IIIb DI can be successfully treated by a combination of intentional replantation and surgical treatment when conventional endodontic therapy fails.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abu Hasna A, Brazil; Memis S, Turkey S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Alkadi M, Almohareb R, Mansour S, Mehanny M, Alsadhan R. Assessment of dens invaginatus and its characteristics in maxillary anterior teeth using cone-beam computed tomography. Sci Rep. 2021;11:19727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vier-Pelisser FV, Pelisser A, Recuero LC, Só MV, Borba MG, Figueiredo JA. Use of cone beam computed tomography in the diagnosis, planning and follow up of a type III dens invaginatus case. Int Endod J. 2012;45:198-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oehlers FA. Dens invaginatus (dilated composite odontome). I. Variations of the invagination process and associated anterior crown forms. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1957;10:1204-18 contd. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ozbas H, Subay RK, Ordulu M. Surgical retreatment of an invaginated maxillary central incisor following overfilled endodontic treatment: a case report. Eur J Dent. 2010;4:324-328. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kumar H, Al-Ali M, Parashos P, Manton DJ. Management of 2 teeth diagnosed with dens invaginatus with regenerative endodontics and apexification in the same patient: a case report and review. J Endod. 2014;40:725-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Agrawal PK, Wankhade J, Warhadpande M. A Rare Case of Type III Dens Invaginatus in a Mandibular Second Premolar and Its Nonsurgical Endodontic Management by Using Cone-beam Computed Tomography: A Case Report. J Endod. 2016;42:669-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Martins JNR, da Costa RP, Anderson C, Quaresma SA, Corte-Real LSM, Monroe AD. Endodontic management of dens invaginatus Type IIIb: Case series. Eur J Dent. 2016;10:561-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gallacher A, Ali R, Bhakta S. Dens invaginatus: diagnosis and management strategies. Br Dent J. 2016;221:383-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ricucci D, Siqueira JF Jr. Fate of the tissue in lateral canals and apical ramifications in response to pathologic conditions and treatment procedures. J Endod. 2010;36:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Siqueira JF Jr, Rôças IN, Hernández SR, Brisson-Suárez K, Baasch AC, Pérez AR, Alves FRF. Dens Invaginatus: Clinical Implications and Antimicrobial Endodontic Treatment Considerations. J Endod. 2022;48:161-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peer M. Intentional replantation - a 'last resort' treatment or a conventional treatment procedure? Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:48-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mainkar A. A Systematic Review of the Survival of Teeth Intentionally Replanted with a Modern Technique and Cost-effectiveness Compared with Single-tooth Implants. J Endod. 2017;43:1963-1968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li N, Xu H, Kan C, Zhang J, Li S. Retrospective Study of Intentional Replantation for Type IIIb Dens Invaginatus with Periapical Lesions. J Endod. 2022;48:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yu YH, Kim M, Kratchman S, Karabucak B. Surgical management of lateral lesions with intentional replantation in single-rooted mandibular first premolars with radicular groove: 2 case reports. J Am Dent Assoc. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ponce EH, Vilar Fernández JA. The cemento-dentino-canal junction, the apical foramen, and the apical constriction: evaluation by optical microscopy. J Endod. 2003;29:214-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xu T, Tay FR, Gutmann JL, Fan B, Fan W, Huang Z, Sun Q. Micro-Computed Tomography Assessment of Apical Accessory Canal Morphologies. J Endod. 2016;42:798-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Barthel CR, Zimmer S, Trope M. Relationship of radiologic and histologic signs of inflammation in human root-filled teeth. J Endod. 2004;30:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dammaschke T, Witt M, Ott K, Schäfer E. Scanning electron microscopic investigation of incidence, location, and size of accessory foramina in primary and permanent molars. Quintessence Int. 2004;35:699-705. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kim S, Kratchman S. Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: a review. J Endod. 2006;32:601-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |