Published online Jun 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6227

Peer-review started: December 13, 2021

First decision: January 8, 2022

Revised: January 24, 2022

Accepted: April 28, 2022

Article in press: April 28, 2022

Published online: June 26, 2022

Processing time: 185 Days and 3.6 Hours

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has been proposed as an effective and durable treatment for severe obesity and glucose metabolism disorders, and its prevalence has increased from 5% to 37% since 2008. One common complication after bariatric surgery is a postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemic state. While rare, insulinomas can cause this state, where symptoms are more common in the fasting state; thus, evaluation of insulin secretion is needed. Until now, there have been no reports of insulinoma after LSG.

We describe the case of a 43-year-old woman who was referred to the obesity clinic 2 years after LSG was performed. She had symptoms of hypoglycemia predominantly in the fasting state and documented hypoglycemia of less than 30 mg/dL, which are compatible with Whipple’s triad. Initially, dumping syndrome was suspected, but after a second low fasting plasma glucose was documented, a 72-h fasting test was performed that tested positive. Computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasound were performed, identifying the presence of a homo

Insulinoma after LSG is a rare condition, and clinicians must be aware of it, especially if the patient has hypoglycemic symptoms during the fasting state.

Core Tip: Neuroglycopenic symptoms compatible with Whipple’s triad were identified in a woman 2 years after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, predominantly occurring in the fasting state. After discarding late dumping syndrome, a 72-h fasting test was performed and tested positive. Imaging techniques documented the presence of a tumoral lesion in the pancreas, compatible with insulinoma. After laparoscopic enucleation of the insulinoma, the symptoms were relieved. When hypoglycemia occurs after bariatric surgery, evaluation of insulin secretion is needed to conduct a correct diagnostic approach. Follow-up must be performed by a multidisciplinary team.

- Citation: Lobaton-Ginsberg M, Sotelo-González P, Ramirez-Renteria C, Juárez-Aguilar FG, Ferreira-Hermosillo A. Insulinoma after sleeve gastrectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(18): 6227-6233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i18/6227.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.6227

The obesity pandemic has become a great topic of interest due to its implications for quality of life, comorbidities, increasing mortality, and the economic impact on health services worldwide[1]. Bariatric surgery (BS) is an effective and durable treatment for severe obesity and glucose metabolism disorders, with laparoscopic Roux-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) being the most common procedure[2,3]. Nevertheless, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has been proposed as a procedure capable of achieving the same goals, but with fewer complications[4].

A common complication in BS is the development of a postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemic state[5]. Hypoglycemia is defined as a glucose level below 70 mg/dL according to the American Dia

A review of the medical literature for insulinoma and hypoglycemia after BS was performed in PubMed. We searched “insulinoma”, “hypoglycemia”, “sleeve gastrectomy”, “RYGB”, “glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1)”, and “ghrelin” and a combination of the above terms including all dates up to October 2021. Herein, we present the case of a 43-year-old woman referred to the obesity clinic due to neuroglycopenic symptoms caused by an insulinoma 2 years after a sleeve gastrectomy.

A 43-year-old woman was referred to the obesity clinic due to neuroglycopenic symptoms caused by an insulinoma 2 years after a sleeve gastrectomy.

In March 2020, 2 years after LSG was performed, the patient developed neuroglycopenic symptoms including short-term memory loss, lingual nerve paresthesia, and nonspecific visual alterations predominantly during the morning in a fasting state. These symptoms were suppressed with food intake. Two months later, she visited a physician who documented fasting plasma glucose of 27 mg/dL, and in June 2020, the symptoms occurred more frequently, and she gained 14 kg. In the beginning, late dumping symptoms were suspected, but in September 2020, fasting plasma glucose of 30 mg/dL was docu

In 2002, the patient was diagnosed with obesity and dyslipidemia (high triglycerides and cholesterol with low HDL) and treated with improvements in diet, physical activity, and statins without weight control. In 2016, a gastric balloon was placed, and although her body mass index (BMI) in 2018 was 34.4 kg/m2, LSG was performed.

The patient had no specific personal or family history.

After LSG, the patient weighed 74 kg, and her BMI was 32 kg/m2. The physical examination showed no obvious cardiovascular or respiratory abnormalities. The abdomen was soft, and the only sign was the presence of postsurgery scars.

Upon hospitalization prior to the surgery, the patient’s hemoglobin A1c level was 4.8% (normal range: < 5.7%). The C-peptide value was normal at 3.64 ng/mL (1.1-4.4 ng/mL), and insulin was mildly elevated at 16.40 µUI/mL (3.21-16.30 µUI/mL). Lipid levels indicated dyslipidemia with total cholesterol of 224 mg/dL and LDL-c of 142.8 mg/dL. Other biochemical parameters were normal and only an iron deficiency anemia was documented. Thyroid function was normal, with TSH 2.46 µUI/mL (0.27-4.20 µUI/mL), FT4 1.06 ng/dL (0.93-1.70 ng/dL), and cortisol level 15.04 ug/dL (3.70-19.40 µg/dL), all within the normal range.

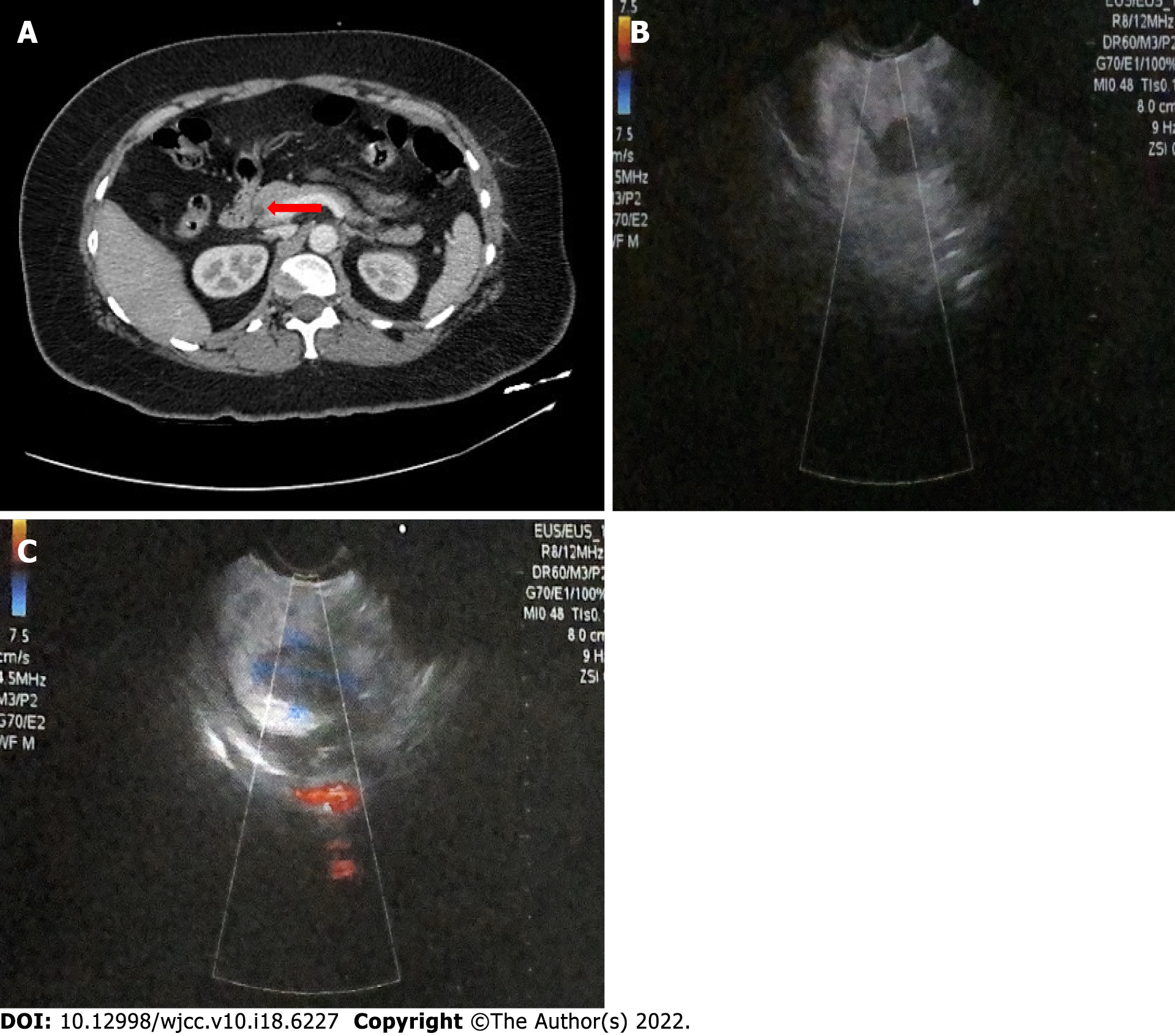

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the presence of a focal asymmetric reinforcement area in the head of the pancreas (Figure 1A). Endoscopic ultrasound showed the presence of a tumoral lesion in the pancreas in close proximity to the main pancreatic duct and splenomesenteric confluence without evidence of invasion (Figure 1B and C).

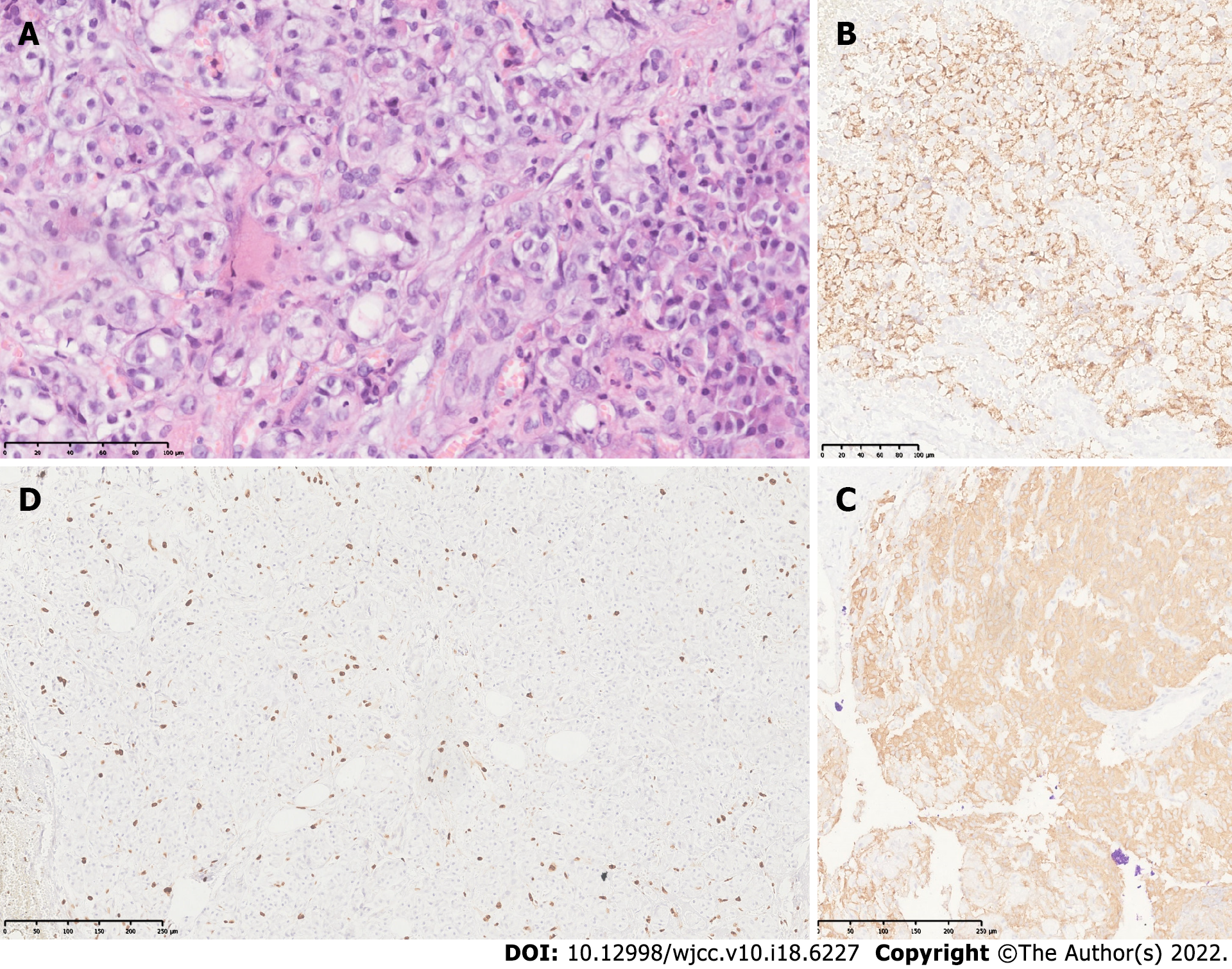

The final diagnosis was insulinoma. This was confirmed by histology and immunohistochemistry of the tumor (Figure 2).

After a surgery consultation, a laparoscopic insulinoma enucleation was performed without complications. No other tumors were identified in the upper abdomen.

Histopathological findings revealed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine grade 2 tumor with free edges. Immunohistochemical studies confirmed positive chromogranin and synaptophysin as well as a proliferative activity (Ki67) in 4% of neoplastic cells.

After surgery, the neuroglycopenic symptoms were relieved, and the patient had no hypoglycemic events. Her current treatment is diet and physical activity, targeting a BMI of 31.1 kg/m2.

Since 2013, 468609 BSs have been performed worldwide[2]. LSG was initially introduced as a first-stage restrictive procedure to a more complex definitive one. At present, it is performed as a stand-alone BS[7]. Since 2008, the prevalence of the LSG procedure has increased from 5% to 37% worldwide[2], but in Mexico, it is performed only in 13% of patients, whereas LRYGB is performed in 85.8%, with a bypass/ sleeve ratio of 7:1. In our center, LSG accounts for 20% of total BSs (200 procedures since 2010).

LSG comprises vertical longitudinal resection of the greater gastric curve that includes the fundus, body, and antrum as well as the formation of a tubular conduit with a capacity of < 100 mL. Weight loss is achieved by restrictive and humoral effects[8,11].

Hypoglycemia is a well-documented complication after BS. Papamargaritis et al[12,13] recorded a study where 33% of patients experienced severe hypoglycemia a year after LSG due to late dumping symptoms, which usually occurs 1-3 h after a high-carbohydrate meal triggering a hyperinsulinemic response. Since 2005, up to 40 cases of nesidioblastosis after RYGB have been reported[8], and only one case after LSG was documented in 2019 by Kim et al[9]. While rare, insulinomas have been reported after BS. Mulla et al[10] described seven cases of insulinoma, one patient with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, and one patient with insulinoma and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor after BS, 78% of whom were women. In these cases, hypoglycemia was more common in the fasting state.

The mechanism of the post-BS hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemic state and the changes in beta cell proliferation are not fully understood. In the LSG, the faster transit of undigested nutrients to the distal gastrointestinal tract due to rapid gastric emptying upregulates the production of GLP-1 secreted by enteroendocrine L cells in the distal intestine. This increase can normalize blood glucose and regulate insulin synthesis and proinsulin gene expression, as well as glucagon and somatostatin secretion[3]. GLP-1 has multiple beneficial effects on β cells, including an increase in their number by inhibiting apoptosis and enhancing neogenesis as well as promoting its proliferation. In a study carried out in 2016 by Xu et al[14], it was found that a chemically modified GLP-1 (mGLP-1) analog promotes the proliferation of pancreatic mouse β cells, upregulating the expression of cyclin E, CDK2, Bcl-2, Bax, and p21. The cyclin E-CDK2 complex plays an important role in the regulation of the G1 phase of the G1/S cell cycle, while p21 is a universal cyclin-dependent kinase (CKI) inhibitor. Meanwhile, the Bcl-2 and Bax genes, two important members of the Bcl-2 gene family, have opposite functions, inhibiting or promoting cell apoptosis, respectively[14].

An increase in ghrelin levels has been observed a year after BS[15]. Ghrelin and the type 1a ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1A) are expressed in different types of neuroendocrine tumors. Recently, Wu et al[16] found that GHS-R1a was found in 60% of insulinomas, suggesting that ghrelin may act through autocrine or paracrine pathways. The proliferative effects of ghrelin and its association with insulinoma have not been studied, although there is a clinical case report where a ghrelin-producing neuroendocrine tumor was transformed into an insulinoma[17].

The diagnosis of hypoglycemia after BS is challenging. The first step after identifying the presence of symptoms is to verify their relationship to hypoglycemia. A detailed clinical history must be performed to identify family or personal history of neuroendocrine tumors, if patients are taking any hypoglycemic medication such as sulfonylureas or if the symptoms are more common in fasting state, as in our case.

In a stepwise manner, biochemical analysis must be performed to rule out other causes[18]. Plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, proinsulin, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and cortisol levels should be measured. The development of provocative studies such as a 72-h fasting test is also recommended[10,18]. The goal is to determine whether beta-cell peptides are appropriately suppressed during hypoglycemia. If autonomous insulin secretion is identified, insulinoma should be suspected[10,18]. The next step is to determine the anatomical localization and to exclude other tumors. Multidetector contrast-enhanced imaging CT or dual phase helical CT with thin sections are the preferred initial imaging options. In patients in whom noninvasive radiologic techniques are negative or to improve the sensitivity for identifying an insulinoma, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) must be performed. EUS has 80%-92% sensitivity for detecting tumors as small as 5 mm. Additionally, EUS-guided fine needle aspiration allows pathologic confirmation in 57% of patients. If the techniques mentioned above fail to detect the tumor, selective arteriography and intra-arterial calcium stimulation tests with hepatic venous sampling can be performed. They should be used only as a last resort because they are invasive techniques[5,10]. In our case, we performed CT and EUS that allowed us to identify insulinoma.

Finally, histopathologic and immunohistochemical confirmation is necessary to classify the type of tumor and to determine the patient’s follow-up[19].

The definitive treatment for insulinoma comprises complete surgical resection. However, there are other treatment options such as octreotide or EUS-guided alcohol tumor ablation, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), or embolization[20]. There is superior short-term recovery, shorter length of stay, decreased hemorrhage, and improved cosmesis when performing minimally invasive pancreatic resection compared to open pancreatic surgery[10]. However, the technique used depends on the size, extension, localization, and type of lesion. Atypical resection, including enucleation and partial or middle pancreatectomy, has the advantage of pancreatic parenchyma preservation, thereby reducing the risk of late exocrine and/or endocrine insufficiency[20]. As in the case of our patient, when the lesion was small, benign, solitary, and superficial and when the pancreatic duct was not involved, the best surgical approach was laparoscopic enucleation[21]. It is important to note that positive resection margins are not associated with increased recurrence rates[10].

This is the first case of insulinoma after sleeve gastrectomy. Although this is a very rare case, clinicians must be aware of it, especially if the patient has hypoglycemic symptoms during the fasting state.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country/Territory of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ding XJ, China; Zhou ST, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Molina-Ayala M, Rodríguez-González A, Albarrán-Sánchez A, Ferreira-Hermosillo A, Ramírez-Rentería C, Luque-de León E, Bosco-Garate I, Laredo-Sánchez F, Contreras-Herrera R, Mac Gregor-Gooch J, Cuevas-García C, Mendoza-Zubieta V. [Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients with morbid obesity at the time of hospital admission and one year after undergoing bariatric surgery]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2016;54 Suppl 2:S118-S123. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Belligoli A, Sanna M, Serra R, Fabris R, Pra' CD, Conci S, Fioretto P, Prevedello L, Foletto M, Vettor R, Busetto L. Incidence and Predictors of Hypoglycemia 1 Year After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2017;27:3179-3186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guilbert L, Joo P, Ortiz C, Sepúlveda E, Alabi F, León A, Piña T, Zerrweck C. Safety and efficacy of bariatric surgery in Mexico: A detailed analysis of 500 surgeries performed at a high-volume center. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2019;84:296-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Yang J, Gao Z, Williams DB, Wang C, Lee S, Zhou X, Qiu P. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on fasting gastrointestinal and pancreatic peptide hormones: A prospective nonrandomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:1521-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Malik S, Mitchell JE, Steffen K, Engel S, Wiisanen R, Garcia L, Malik SA. Recognition and management of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2016;10:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S73-S84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 141.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Natoudi M, Panousopoulos SG, Memos N, Menenakos E, Zografos G, Leandros E, Albanopoulos K. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity and glucose metabolism: a new perspective. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1027-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Service GJ, Thompson GB, Service FJ, Andrews JC, Collazo-Clavell ML, Lloyd RV. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with nesidioblastosis after gastric-bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:249-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 591] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim A, Snaith JR, Mahajan H, Holmes-Walker DJ. Nesidioblastosis following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2019;91:906-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mulla CM, Storino A, Yee EU, Lautz D, Sawnhey MS, Moser AJ, Patti ME. Insulinoma After Bariatric Surgery: Diagnostic Dilemma and Therapeutic Approaches. Obes Surg. 2016;26:874-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gjeorgjievski M, Imam Z, Cappell MS, Jamil LH, Kahaleh M. A Comprehensive Review of Endoscopic Management of Sleeve Gastrectomy Leaks. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:551-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Papamargaritis D, Koukoulis G, Sioka E, Zachari E, Bargiota A, Zacharoulis D, Tzovaras G. Dumping symptoms and incidence of hypoglycaemia after provocation test at 6 and 12 months after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1600-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Scarpellini E, Arts J, Karamanolis G, Laurenius A, Siquini W, Suzuki H, Ukleja A, Van Beek A, Vanuytsel T, Bor S, Ceppa E, Di Lorenzo C, Emous M, Hammer H, Hellström P, Laville M, Lundell L, Masclee A, Ritz P, Tack J. International consensus on the diagnosis and management of dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:448-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu F, Wang KY, Wang N, Li G, Liu D. Bioactivity of a modified human Glucagon-like peptide-1. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Navarro García MI, González-Costea Martínez R, Torregrosa Pérez N, Romera Barba E, Periago MJ, Vázquez Rojas JL. Fasting ghrelin levels after gastric bypass and vertical sleeve gastrectomy: An analytic cohort study. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed). 2020;67:89-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu HY, Li NS, Song YL, Bai CM, Wang Q, Zhao YP, Xiao Y, Yu S, Li M, Chen YJ. Plasma levels of acylated ghrelin in patients with insulinoma and expression of ghrelin and its receptor in insulinomas. Endocrine. 2020;68:448-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chauhan A, Ramirez RA, Stevens MA, Burns LA, Woltering EA. Transition of a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor from ghrelinoma to insulinoma: a case report. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;6:E34-E36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sheehan A, Patti ME. Hypoglycemia After Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery: Clinical Approach to Assessment, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:4469-4482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Patti ME, Goldfine AB, Hu J, Hoem D, Molven A, Goldsmith J, Schwesinger WH, La Rosa S, Folli F, Kulkarni RN. Heterogeneity of proliferative markers in pancreatic β-cells of patients with severe hypoglycemia following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:737-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Sumiyoshi T, Kozuki A, Ito S, Ogawa Y, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Diagnosis and management of insulinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:829-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 21. | Liu J, Zhang CW, Hong DF, Wu J, Yang HG, Chen Y, Zhao DJ, Zhang YH. Laparoscope resection of retroperitoneal ectopic insulinoma: a rare case. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4413-4418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |