Published online Jun 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i17.5798

Peer-review started: November 23, 2021

First decision: February 7, 2022

Revised: February 27, 2022

Accepted: April 15, 2022

Article in press: April 15, 2022

Published online: June 16, 2022

Processing time: 197 Days and 21.8 Hours

Hepatic artery aneurysm (HAA) is the second most common visceral aneurysm. A significant number of hepatic aneurysms are found accidentally on examination. However, their natural history is characterized by their propensity to rupture, which is very serious and requires urgent treatment. An emergent giant hepatic aneurysm with an abdominal aortic dissection is less commonly reported.

We report the complicated case of a giant hepatic aneurysm with an abdominal aortic dissection. A 66-year-old female presented with the complaint of sudden upper abdominal pain accompanied by vomiting. Physical examination showed that her blood pressure was 214/113 mmHg. Her other vital signs were stable. Computed tomography found a giant hepatic proper aneurysm and dissection of the lower segment of the abdominal aorta. Furthermore, angiography showed a HAA with the maximum diameter of approximately 56 mm originating from the proper hepatic artery and located approximately 15 mm from the involved bifurcation of the left and right hepatic arteries with no collateral circulation. Therefore, we decided to use a stent to isolate the abdominal aortic dissection first, and then performed open repair. After the operation, the patient recovered well without complications, and her 3-month follow-up checkup did not reveal any late complications.

Open surgery is a proven method for treating giant hepatic aneurysms. If the patient's condition is complex, staged surgery is an option.

Core Tip: We report a relatively rare case of a giant hepatic aneurysm combined with abdominal aortic coarctation. The patient had an acute onset and was treated for abdominal aortic coarctation after blood pressure control, followed by a second stage open surgery to manage the hepatic aneurysm in a comprehensive manner. The patient's prognosis is good.

- Citation: Wen X, Yao ZY, Zhang Q, Wei W, Chen XY, Huang B. Surgical repair of an emergent giant hepatic aneurysm with an abdominal aortic dissection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(17): 5798-5804

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i17/5798.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i17.5798

Hepatic artery aneurysm (HAA) is the second most common visceral aneurysm[1]. The incidence rate of HAA in 2091965 patients who visited the Mayo Clinic between 1980 and 1986 was 0.002%[2]. A total of 77% HAAs are isolated in the proximal part of the liver, of which 20% are combined with parenchymal and extraparenchymal invasion and 3% are confined to the liver[3]. Excluding traumatic aneurysms, patients most commonly suffer from HAAs during their sixth decade of life[4]. Lesions in the hepatic circulation show a ratio of approximately 3:2 in terms of sex with male predominance[2]. Risk factors for HAA include atherosclerosis, medial degeneration, infection, trauma, and vasculitis[4]. A large majority of HAAs are diagnosed incidentally via computed tomography (CT) scan[3]. Most patients with symptomatic aneurysms present with one or more of Quincke's classic triad of biliary bleeding (jaundice, biliary colic, and gastrointestinal bleeding)[4]. Diagnosis can be made by ultrasound scan, CT angiography (CTA), and digital subtraction angiography. CTA is recommended as the diagnostic tool of choice in patients who are thought to have HAA[5]. Despite recent advances in therapeutic techniques and diagnostic tools, the management of a visceral artery aneurysm remains clinically challenging. Rupture is the most emergent and life-threatening situation in HAA. Lumsden et al[4] pointed out that the HAA-related early incidence of rupture and mortality was 9.1% and 22.7%, respectively. Fibromuscular dysplasia and polyarteritis nodosa increase the risk of HAA rupture and account for 50% of HAA ruptures[5]. The majority of these lesions rupture when they are > 2 cm in diameter[3].

The guideline, named “the Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines on the management of visceral aneurysms”, states that all hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms regardless of cause (Grade 1A) and all symptomatic HAAs regardless of size (Grade 1A) should be repaired as soon as possible; in asymptomatic patients without significant comorbidity, repair is recommended if the true HAA is > 2 cm (Grade 1A) or if the aneurysm enlarges at the rate of > 0.5 cm per year (Grade 1C); in patients with significant comorbidities, repair is recommended if the HAA is > 5.0 cm (Grade 1B); furthermore, the repair of HAA in patients with vasculopathy or vasculitis regardless of size (Grade 1C) or with positive blood cultures (Grade 1C) is recommended[5]. The clinical practice guidelines on the management of visceral aneurysms set by the Society for Vascular Surgery indicate that treatment approaches mainly include endovascular repair with covered stents, open repair, and coil embolization. The endovascular approach represents a minimally-invasive alternative with low mortality and morbidity[6]. Given the abundant collateral supply of the liver, the incidence of hepatic necrosis after disruption of the common hepatic artery is low. Percutaneous embolization is of special value in patients with intrahepatic aneurysms[5]. Endovascular therapy has become the mainstream approach. However, open repair remains a therapeutic option with definite efficacy and is mostly chosen under the conditions of HAA rupture, infeasible endovascular approach and for symptomatic patients with fibromuscular dysplasia or polyarteritis nodosa and lesions in the proper hepatic and proximal right or left hepatic branches[5].

A 66-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with the chief complaint of severe abdominal pain with vomiting. Four hours before admission, the patient had a sudden onset of sharp pain in the upper and middle abdomen with no obvious cause. The pain was unbearable and persistent without relief, which involved back pain and was accompanied by vomiting the contents of the stomach, without dizziness, headache, chest tightness, chest pain, acid reflux, heartburn, chills, fever and other symptoms.

The patient was found to have hypertension for more than 20 years, with the highest blood pressure reaching 220/160 mmHg. She was taking nimodipine tablets (30 mg tid) regularly, and her blood pressure was controlled at approximately 140/75 mmHg, usually without dizziness and headache.

The patient had no other previous illnesses.

Her personal and family history was unremarkable.

Physical examination showed slight tenderness in the upper abdomen and no rebound pain; blood pressure of 214/139 mmHg; pulse of 64 beats/min; and temperature of 36.4ºC.

Her blood test results showed no special abnormalities.

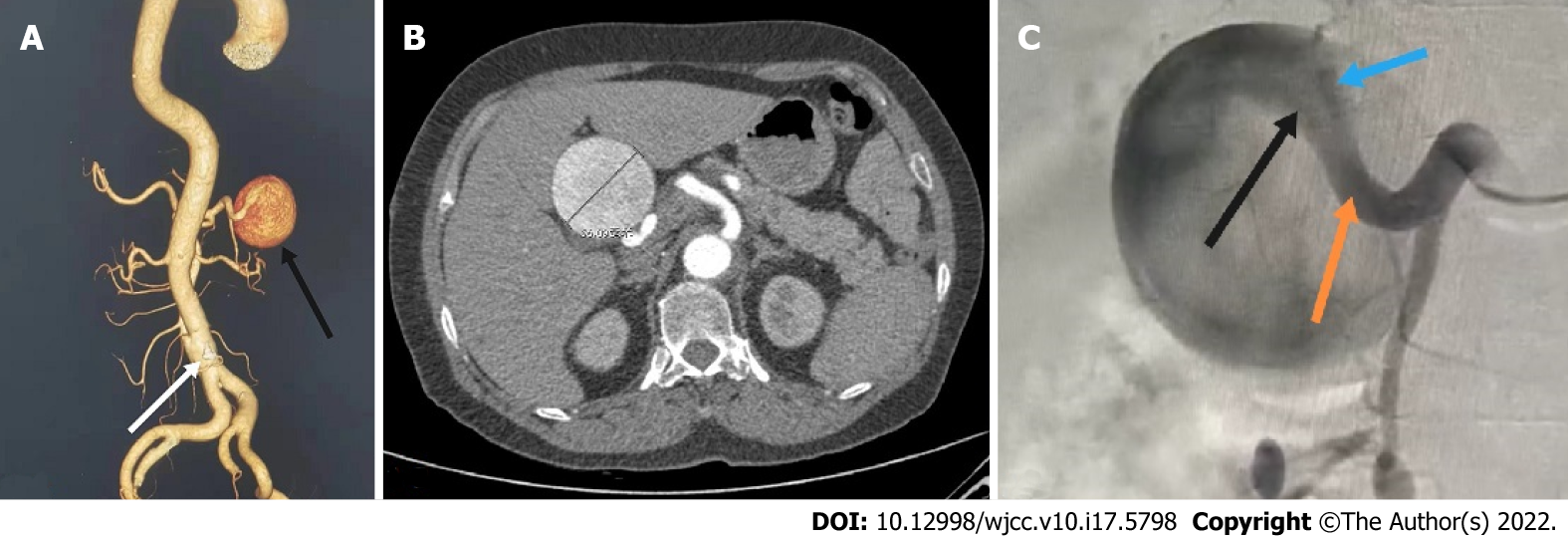

CT revealed: (1) A giant aneurysm of the proper hepatic artery (maximum diameter approximately 56 mm); and (2) Dissection of the lower abdominal aorta (single break) (Figure 1A and B).

The patient was diagnosed with abdominal aortic dissection, hepatic artery aneurysm, and hypertension grade 3 (very high risk).

After receiving blood pressure control, sedation and related symptomatic treatment from the coronary heart disease center of our cardiology department, the patient's symptoms disappeared and her vital signs stabilized. The patient was transferred to our department on the same day of admission due to CT findings of abdominal aortic coarctation and a hepatic aneurysm. We performed angiography, which showed that the HAA had a maximum diameter of approximately 5.6 cm and that it originated from the proper hepatic artery and was located approximately 1.5 cm from the involved bifurcation of the left and right hepatic arteries with no collaterals. Prolonged angiography revealed no communication between the HAA and superior mesenteric artery (Figure 1C). Considering the complexity of the patient's condition, the aortic dissection was repaired with a Endurant II stent graft (Medtronic, Inc.) at the first stage, and the HAA was scheduled for surgical repair at the second stage. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with antiplatelet, lipid-lowering and blood pressure control therapy.

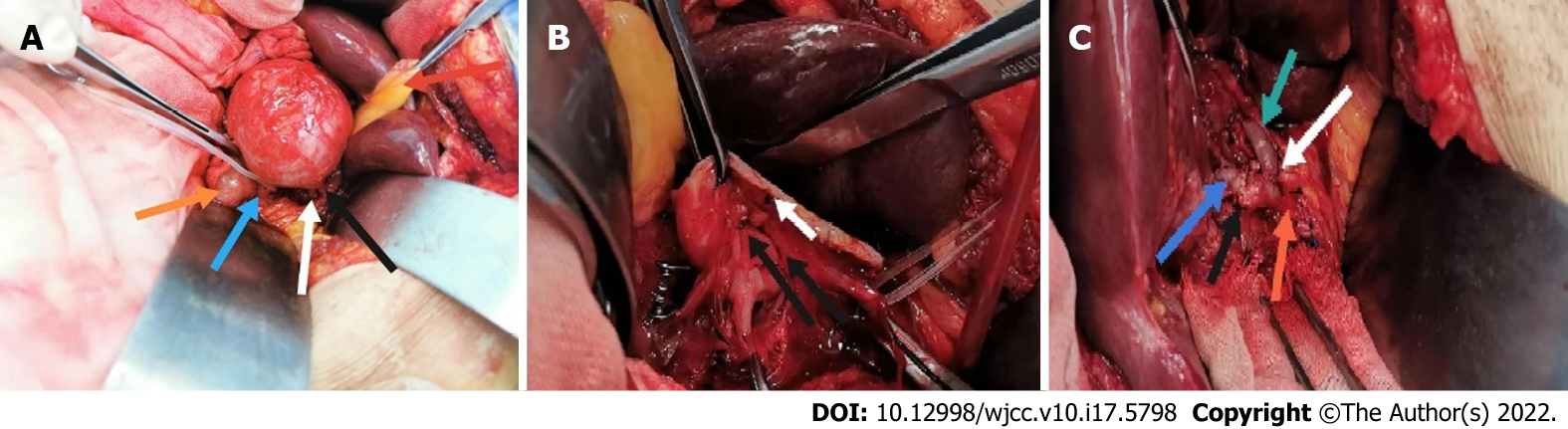

Open repair was performed six days later. A right subcostal incision was made, and the surgical approach was via the small omental sac. Intraoperative findings showed the following: the proper hepatic artery, which was approximately 6 cm × 6 cm in size, was located between the medial side of the descending duodenum and the anterior of the pancreatic head and bile duct (Figure 2A). We then mobilized the inflow and outflow of the proper hepatic artery. After systemic heparinization, the inflow and outflow of the HAA was clamped, and the aneurysm was directly opened. An aneurysm break approximately 2 mm in size and slight mural thrombus (Figure 2B) were found. No collateral vessel was detected in the aneurysm. The proximal part of the proper hepatic artery was anastomosed end to end with the right hepatic artery as the adjacent orifice location, and the left hepatic artery was anastomosed end to side with the proper hepatic artery (Figure 2C). The hepatic artery clamp time was 31 min. After anastomosis, ultrasound revealed the patency of the anastomotic site and the distal hepatic artery branches. The operation was performed without difficulties.

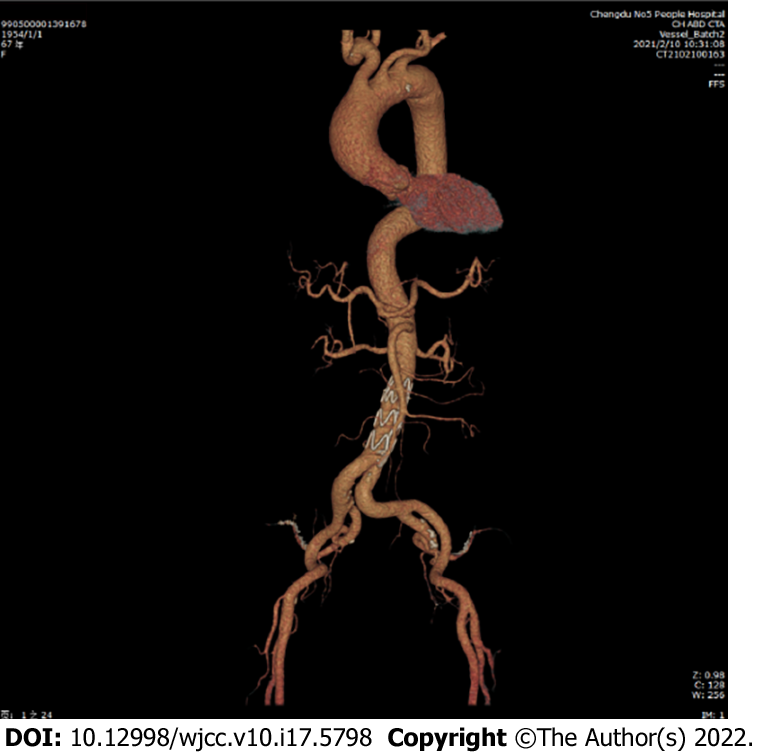

Postoperatively, the patient experienced no specific discomfort. Antiplatelet, blood pressure control, and lipid-lowering treatments were maintained. Eleven days later, the patient was successfully discharged without surgery-related complications. The important times and events during the patient's hospitalization are shown in Table 1. The patient’s 3-mo follow-up checkup did not reveal any late complications (Figure 3). She reported no specific discomfort on review and was very satisfied with her treatment.

| Date | Events |

| December 8, 2020 | (1) The patient was admitted to the emergency department with acute abdominal pain and widespread pulling pain in the back with a blood pressure of 214/139 mmHg at the time of the emergency; (2) Computed tomography (CT) suggested abdominal aortic coarctation with intramural hematoma, hepatic artery aneurysm, bilateral common iliac artery and calcified plaque in the internal iliac artery; and (3) The patient was transferred to our department due to CT findings of abdominal aortic coarctation and hepatic aneurysm |

| December 14, 2020 | Ultrasound showed no special abnormalities in the renal artery and bilateral carotid and vertebral arteries |

| December 23, 2020 | Abdominal aortogram + endoluminal isolation of abdominal aortic coarctation (non-emergency) was performed |

| December 29, 2020 | Hepatic intrinsic aneurysm resection+ hepatic artery reconstruction (non-emergency) was performed |

| January 9, 2021 | The patient was successfully discharged with a good prognosis and without any associated complications |

Visceral aneurysms, despite their rare incidence of 0.01%-0.2%, are of clinical importance, especially if we consider their natural history which is characterized by their propensity to rupture, with HAA accounting for approximately 20% of visceral aneurysms and a rupture rate of 44%[5]. They are usually asymptomatic and difficult to detect until they rupture and cause abdominal pain and hypovolemic shock. As a result, most visceral aneurysms are found incidentally. The mortality rate following ruptured visceral aneurysms remains high (30% reported in the last decade)[7].

The timing of the intervention for hepatic aneurysms has been mentioned above. The treatment of a hepatic aneurysm is mainly as follows: Covered stent, open repair, and embolization[2,3,5]. The ideal surgical option should be to remove the aneurysm while maintaining the hepatic circulation. Therefore, the primary treatment of hepatic aneurysms varies by site. The main treatments for common HAAs include open surgical ligation, endovascular embolization, resection/reconstruction, aneurysmorrhaphy, and a covered stent; those for the proper hepatic artery are resection with arterial reconstruction and endovascular repair with a covered stent; those for the proximal right or left hepatic branches are resection with arterial reconstruction and endovascular stent grafting; and finally, those for an intrahepatic aneurysm are endovascular embolization and resection of the lobe in which the aneurysm is located[5,8]. However, the specific choice of treatment should be based on the patient's specific circumstances.

In this case, we did not select coil embolization mainly for the following reasons: First, the endovascular repair of extrahepatic HAA depends on the collaterals and location of the HAA. Given that the maintenance of distal organ perfusion is important, embolization is usually discouraged in patients with HAAs in the proper hepatic artery due to the risk of liver ischemia[5]. Furthermore, in this case, the location of the HAA in the proper hepatic artery involved the bifurcation of the left and right hepatic arteries with no collateral circulation and thus increased the risk. Second, the HAA was so large that a large parenchymal lesion would be created if we performed embolization; this lesion might compress the biliary tract and duodenum and thus cause jaundice, gastrointestinal obstruction, and even duodenum fistula[5,9].

Another main option for HAA repair is endovascular stent grafting. The endovascular repair of visceral aneurysms with stent implantation can simultaneously enable aneurysm exclusion and vascular preservation, and therefore minimize the risk of ischemic complications[10]. Nearly all retrospective case series have shown that although the outcomes for visceral artery aneurysms after open or endovascular repair share similar long-term results, morbidity is significantly worse with open repair than with the endovascular approach[5,8]. The scope of aneurysm morphology suitable for endovascular repair is expanding with the accumulation of experience and improvements in equipment. The anatomical complexity of aneurysms is generally believed to affect the technical difficulty of repair with the development of the application of endovascular covered grafts; this belief is the main reason why we did not choose the approach of endovascular covered grafting. The main complications of endovascular stent grafting include occlusion[9,11]. However, the patency rate of hepatic artery stenting is rarely reported. Künzle et al[12] reported that the 2-year patency of the endovascular stent grafting of visceral artery aneurysms is approximately 81%.

Open surgery, which is usually known as open surgical revascularization, is another common method for the treatment of HAA. Considering the possibility of central liver necrosis despite adequate collateral flow by endovascular exclusion, open repair is recommended in low-risk patients if endovascular stent graft exclusion is not possible[5]. In addition, open surgery has its unique role in aneurysm rupture.

The main methods of vascular reconstruction include direct vascular anastomosis and bypass of the artificial vascular or saphenous vein and vascular patch[11]. The main complications of open surgical revascularization are infection and occlusion. Erben et al[11] reported that in open surgical revascularization, the incidence of occlusion is 12%, with saphenous veins and artificial vessels sharing 6% and 6% equally, and the incidence of infection is 6%.

In this case, deploying the covered stent was difficult considering the tortuosity of the delivery route. Therefore, the proper hepatic artery was anastomosed end to end with the right hepatic artery, and the left hepatic artery was anastomosed end to side with the proper hepatic artery without an artificial blood vessel or saphenous vein. This approach was riddled with the considerations discussed above. First, we anastomosed the blood vessels directly because the ends were highly adjacent, and the tension was low after direct anastomosis with no need for the use of artificial blood vessels or saphenous veins, so that the patient could reduce the subsequent anticoagulant burden. Second, we did not first anastomose the left and right hepatic arteries and then anastomose them with the proper hepatic artery as during the operation, we found that the patient’s right hepatic artery was thick and large, so that we could prevent complications in one of the left and right hepatic arteries from affecting the other artery to the greatest extent. Moreover, we did not completely isolate the whole aneurysm, thus reducing the damage to the surrounding tissue and the incidence of postoperative complications. During the entire operation, the hepatic artery occlusion time was 31 min, which reduced the probability of hepatic ischemia.

Diagnosing huge hepatic aneurysms in time and choosing the best treatment are very challenging. When other serious diseases, such as Stanford type B aortic dissection, are found at the same time, the complexity of the patient's condition and the difficulty of treatment double. Although endovascular therapy is the first choice in most cases, open surgery still has a unique role. We should not only strictly understand the indications of various surgical procedures, but also make clinical decisions in accordance with the specific conditions of patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Baran B, Turkey; Covantsev S, Russia; Stepanyan SA, Armenia S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Pulli R, Dorigo W, Troisi N, Pratesi G, Innocenti AA, Pratesi C. Surgical treatment of visceral artery aneurysms: A 25-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:334-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Abbas MA. Hepatic artery aneurysm: factors that predict complications. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:41-45. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Berceli SA. Hepatic and splenic artery aneurysms. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18:196-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lumsden AB, Mattar SG, Allen RC, Bacha EA. Hepatic artery aneurysms: the management of 22 patients. J Surg Res. 1996;60:345-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chaer RA, Abularrage CJ, Coleman DM, Eslami MH, Kashyap VS, Rockman C, Murad MH. The Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines on the management of visceral aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:3S-39S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 66.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. The RUSH exam: Rapid Ultrasound in SHock in the evaluation of the critically lll. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:29-56, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haghighatkhah H, Sanei Taheri M, Kharazi SM, Zamini M, Rabani Khorasgani S, Jahangiri Zarkani Z. Hepatic Artery Aneurysms as a Rare but Important Cause of Abdominal Pain; a Case Series. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019;7:e25. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Cochennec F, Riga CV, Allaire E, Cheshire NJ, Hamady M, Jenkins MP, Kobeiter H, Wolfe JN, Becquemin JP, Gibbs RG. Contemporary management of splanchnic and renal artery aneurysms: results of endovascular compared with open surgery from two European vascular centers. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:340-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen X, Ge J, Zhao J, Yuan D, Yang Y, Huang B. Duodenal Necrosis Associated with a Threatened Ruptured Gastroduodenal Artery Pseudoaneurysm Complicated by Chronic Pancreatitis: Case Report. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;68:571.e9-571.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Venturini M, Marra P, Colombo M, Panzeri M, Gusmini S, Sallemi C, Salvioni M, Lanza C, Agostini G, Balzano G, Tshomba Y, Melissano G, Falconi M, Chiesa R, De Cobelli F, Del Maschio A. Endovascular Repair of 40 Visceral Artery Aneurysms and Pseudoaneurysms with the Viabahn Stent-Graft: Technical Aspects, Clinical Outcome and Mid-Term Patency. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:385-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Erben Y, De Martino RR, Bjarnason H, Duncan AA, Kalra M, Oderich GS, Bower TC, Gloviczki P. Operative management of hepatic artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:610-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Künzle S, Glenck M, Puippe G, Schadde E, Mayer D, Pfammatter T. Stent-graft repairs of visceral and renal artery aneurysms are effective and result in long-term patency. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:989-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |