Published online May 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4288

Peer-review started: November 18, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: December 31, 2021

Accepted: March 6, 2022

Article in press: March 6, 2022

Published online: May 6, 2022

Processing time: 162 Days and 13.2 Hours

Determining a subdural hematoma (SDH) to be chronic by definition takes 3 wk, whereas organized chronic SDH (OCSDH) is an unusual condition that is believed to form over a much longer period of time, which generally demands large craniotomy. Therefore, it is a lengthy process from the initial head trauma, if any, to the formation of an OCSDH. Acute SDH (ASDH) with organization-like, membranaceous appearances has never been reported.

A 56-year-old woman presented to our hospital with a seizure, and computed tomography (CT) on admission was negative for signs of intracranial hemorrhage. She had clear consciousness and unimpaired motor functions on arrival and remained stable for the following week, during which she underwent necessary examinations. On the morning of day 10 of hospitalization, she accidentally hit her head hard against the wall in the bathroom and promptly lapsed into complete coma within 2 h. Therefore, we performed emergency CT and identified a left supratentorial SDH that was an absolute indication for surgery. However, the intraoperative findings were surprising, with no liquefaction observed. Instead, a solid hematoma covered with a thick membrane was noted that strongly resembled an organized hematoma. Evacuation was successful, but the family stopped treatment the next day due to financial problems, and the patient soon died.

Neurosurgeons should address SDHs, especially ASDHs, with discretion and individualization due to their highly diversified features.

Core Tip: Through unknown mechanisms, a minority of chronic subdural hematomas (SDHs) tend to be organized in the end with the prerequisite of being chronic. It takes a long time to form encapsulating membranes, as was traditionally thought. We report a rare case of enigmatic rapid encapsulation of an acute SDH, which, according to the definition, cannot be considered organized. Such a rapid formation of thick membranes around an acute SDH is rare and will certainly make the procedure, if needed, unpredictable. We may also need to review the natural history of SDH.

- Citation: Lv HT, Zhang LY, Wang XT. Enigmatic rapid organization of subdural hematoma in a patient with epilepsy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(13): 4288-4293

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i13/4288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4288

Subdural hematomas (SDHs) following traumatic head injury constitute an essential proportion of the cases seen in daily practice in the field of neurosurgery. An SDH is considered chronic (CSDH) when it is discovered > 3 wk after the initiating trauma[1]. Organized chronic SDH (OCSDH) is a rare category of CSDH characterized by the formation of areas of solid consistency encapsulated by thick membranes[2,3], which has been extensively reported regarding the diagnosis, treatment options and outcomes. Only a minority of CSDHs develop into OCSDHs, and OCSDHs have various clinical manifestations. Although the mechanisms underlying the development of OCSDHs in these cases remain unclear, the process of hematoma organization is undoubtedly slow (probably lasting at least 6 mo)[2,4,5]. It is conceivable that OCSDH develops only when the hematoma is chronic. By reviewing the literature, we found no previous reports of the rapid formation of membranes around a hematoma, causing it to appear organized, which is an interesting presentation. In this article, we report a rare case of organized acute SDH (ASDH) with an unusual appearance found in a deceptively simple craniotomy performed to evacuate a hematoma, and we believe this is the first report of this phenomenon.

A 56-year-old female farmer had a seizure 13 h prior to presentation along with a slight fever.

The patient developed a cold approximate 5 d prior to presentation after being exposed to rain. After a careful investigation of her history, we learned that the patient had two separate tonic-clonic seizures 2-3 h after the primary seizure, characterized by oral and linguistic automatism in sleeping.

Her major medical history included hypertension and diabetes for > 10 years; both of which were marginally controlled by medication, a hysteromyomectomy 20 years before, cerebral infarction 12 years before, and renal dysfunction incidentally detected 3 years before of unknown current extent.

Three of her family members, including the patient’s mother and two brothers, died of bronchitis. The brothers passed away at young ages.

The patient exhibited clear consciousness and normal motor function [Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) 15 points] with occasional delirious speech and a positive Babinski sign on the right side. Both pupils were 3 mm in diameter (d) and sensitive to light. No other specific physical signs were found.

Laboratory assessments showed a high level of C-reactive protein (9.47 mg/L, reference range 0-8.0 mg/L); compromised renal function, with high serum creatinine (164 μmol/L, reference range 46-92 μmol/L); high blood urea (13.53 mmol/L, reference range 2.90-8.20 mmol/L); and increased serum myoglobin (268.35 ng/mL, reference range < 110 ng/mL). The test results for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained through a lumbar puncture were uneventful.

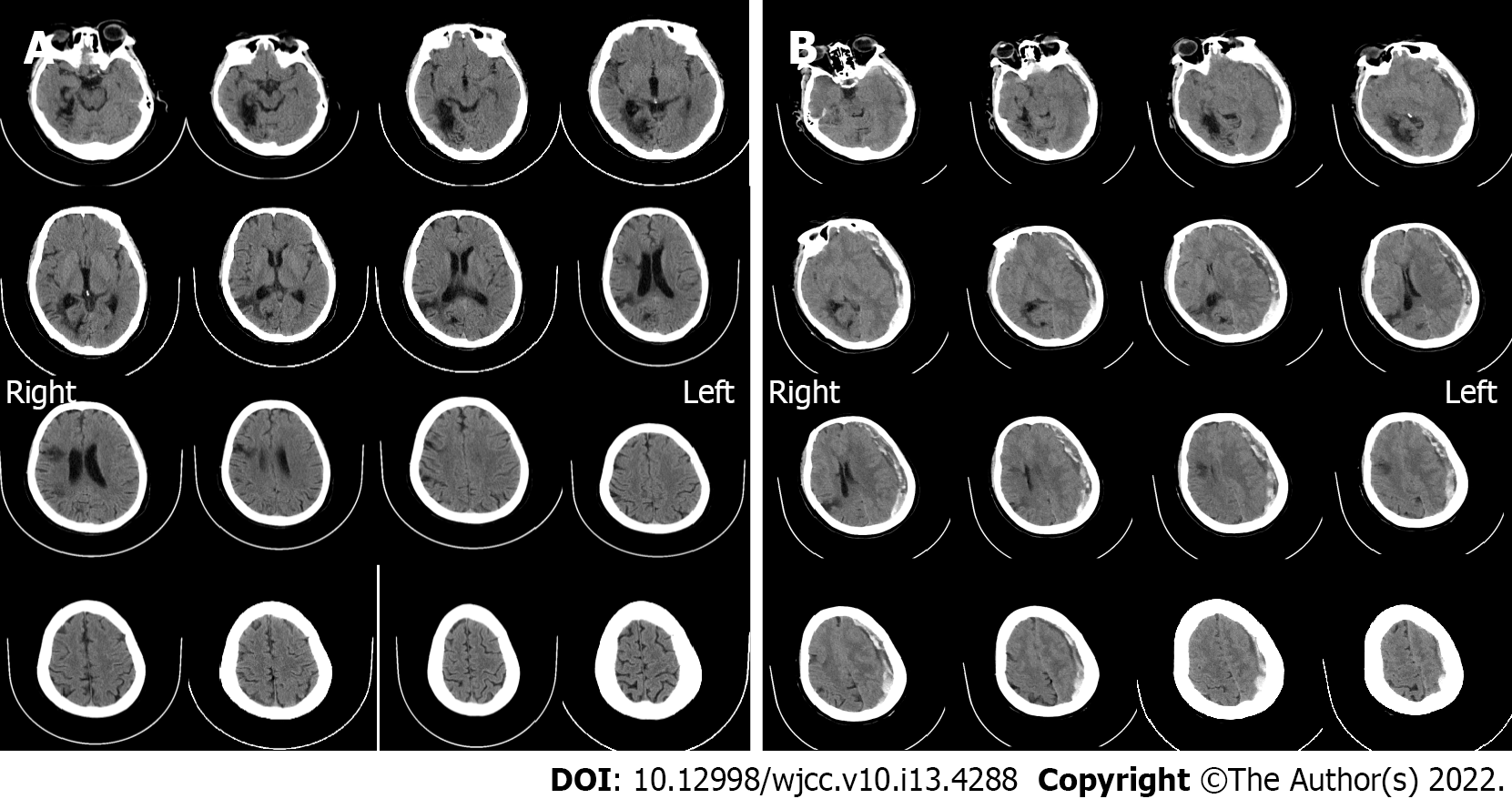

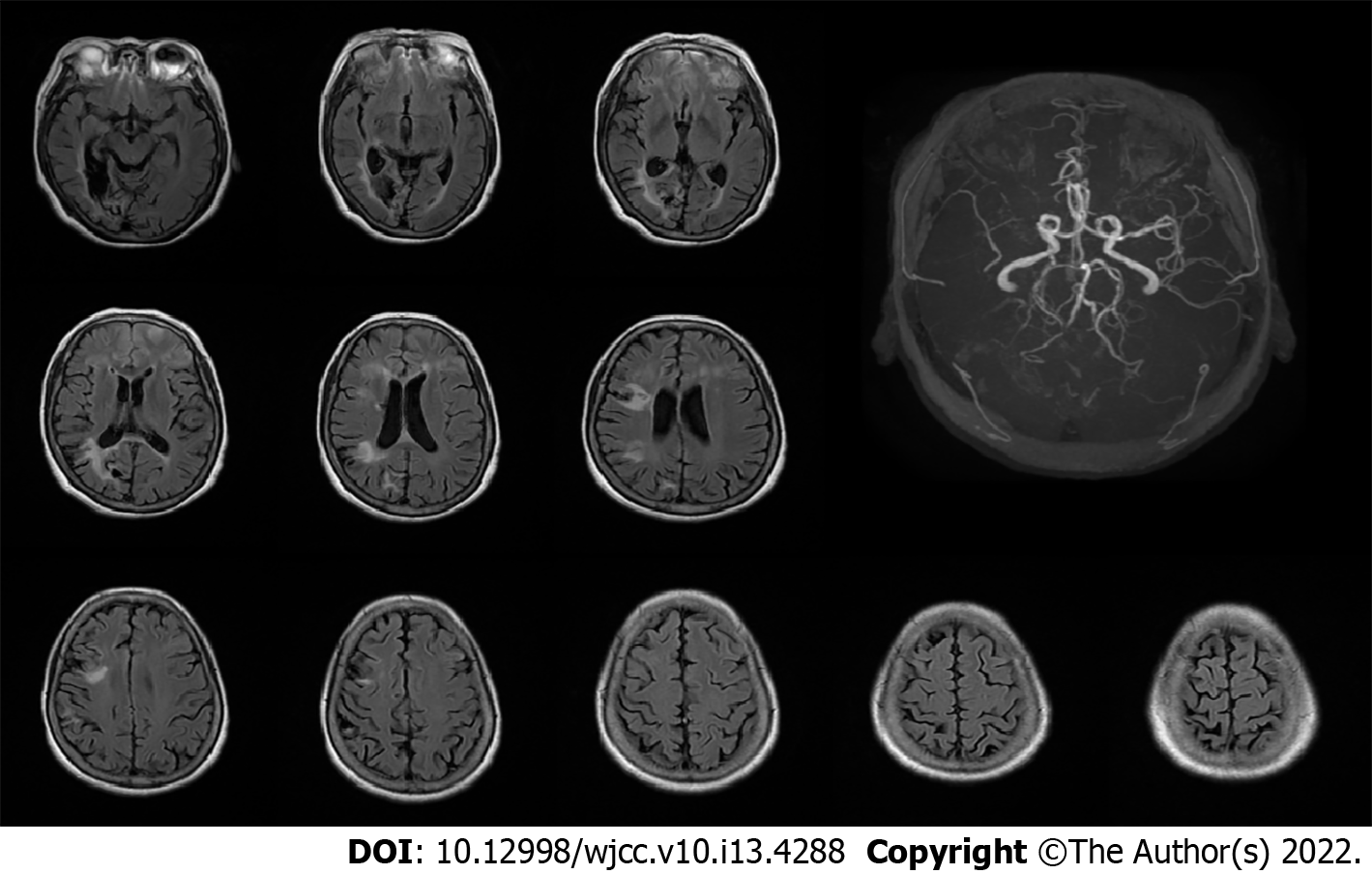

Computed tomography (CT) on admission showed multiple malacia sites, mainly in the right lobe, without any signs of hemorrhage (Figure 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on day 3 after admission showed no signs of intracranial hemorrhage (Figure 2). On the morning of day 10 after admission, sudden deterioration of the patient prompted us to perform emergency CT, which showed a left supratentorial SDH with considerable mass effect (Figure 1B).

The main diagnosis was symptomatic epilepsy and ASDH.

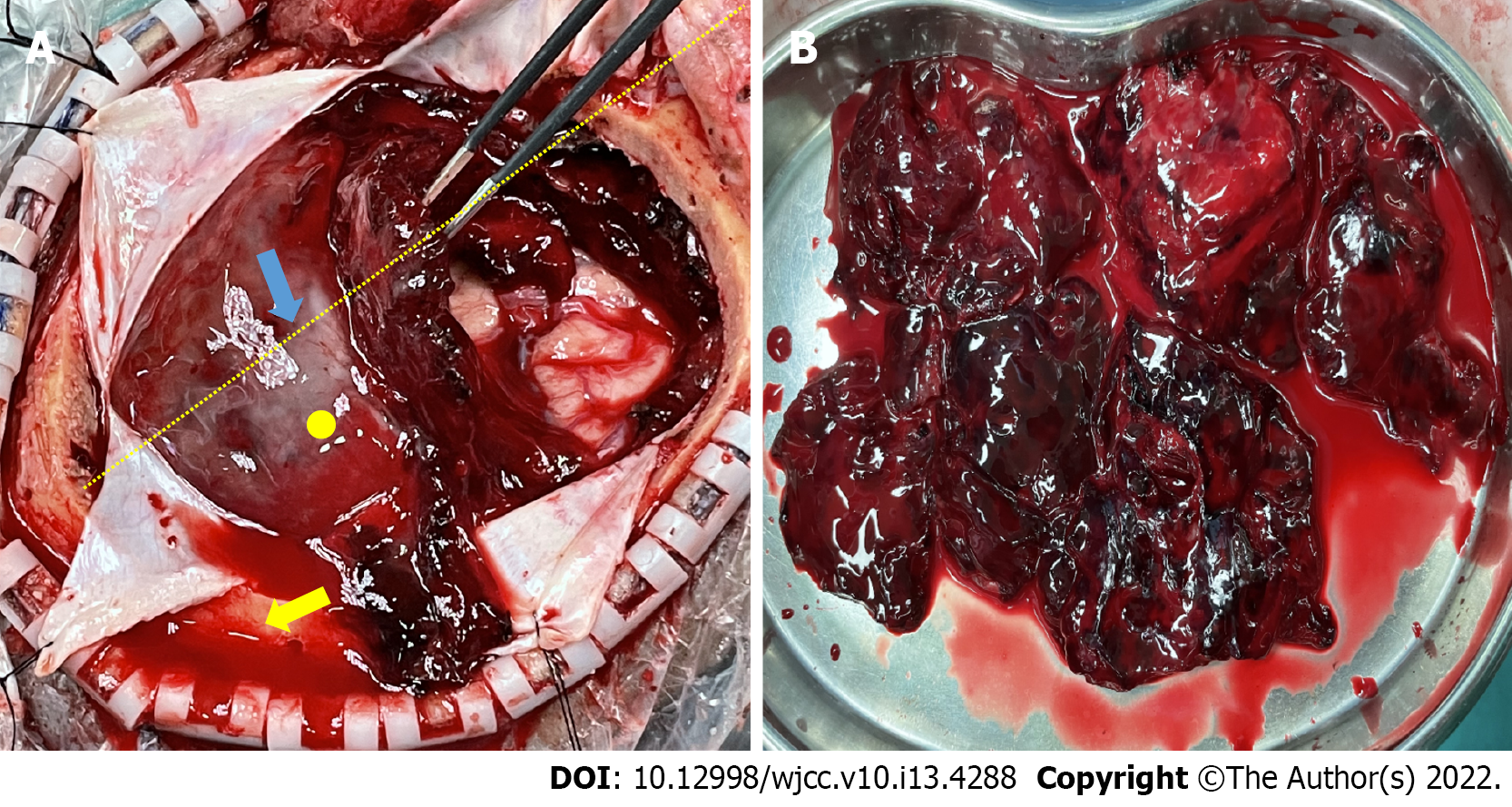

The process of treatment was rather dramatic. Immediate antiepileptic treatment as well as treatment for the comorbidities were administered on admission, and the patient seemed to remain stable over the course of the following week while necessary examinations were conducted. Just when we thought everything was going well, surprisingly, the patient experienced projectile vomiting and a severe headache on the morning of day 10. However, only 20 min later, she began to show arresting weakness on her right side but she could still response to calling and her pupils were good. We ran an emergency CT scan (Figure 1B). By the time the patient was returned to her room, she was in complete coma [GCS 5 points, E (eye opening) 1 points; V (verbal response) 1 points; M (motor response) 3 points], and her left pupil was dilated to 4 mm and fixed. After quickly debriefing her family members on the life-threatening situation, we operated as soon as possible with large craniotomy. The intraoperative findings were surprising. The hematoma strongly resembled an organized hematoma and assumed a form we had not previously observed. We inclined to think the hematoma was acute according to the clinical course and CT scan despite some low-density components inside it. Therefore, the observation of the absence of a liquefied hematoma with only a small amount of clear CSF when we started to open the dura mater was an anomaly. The hematoma was better exposed after we cut the dura completely open in a cruciform fashion, and we found it under a solid covering of a thick membrane (Figure 3). This finding made us even more confused because we were confident that it was definitely not a CSDH based on strong evidence of recent CT and MRI scans. The flap range was believed to be sufficient for a typical ASDH but not necessarily for an organized hematoma, so a tentative tumorectomy-like technique was used to remove the hematoma in pieces. Fortunately, the attempt proved successful, which enabled us to evacuate the hematoma thoroughly without any unwanted damage. However, the subarachnoid space macroscopically appeared dry, and a thinnish inner membrane of the hematoma was detected that did not adhere significantly over the brain surface (Figure 3). We washed the cavity with plenty of saline until it cleared, during which minor frontal lobe superficial arterial bleeding was easily controlled by bipolar electrocoagulation hemostasis. The procedure was successful. The brain tissue remained collapsed without emerging pulsations before closure, and the patient was then transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further observation.

We performed an electroencephalogram on day 2 after admission, but re-examination was required for conclusive findings. However, we were unable to perform the re-examination due to the unexpected craniotomy. On day 3, MRI revealed nothing to alert us to the hemorrhage. Another day later (day 4 of hospitalization), we tested her CSF by a regular lumbar puncture. The pressure was approximately 190 mmH2O, and approximate 7 mL of clear CSF was obtained and sent for evaluation. On the morning of day 9, the patient suffered a gelastic seizure without warning that was later disassembled by injection of diazepam and dilantin, representing the only recurrence since admission. Then on day 10, it happened as above. However, the husband revealed that the patient hit her head heavily against the wall in a bathroom several minutes prior to deterioration. Carelessness was to blame for her injury, according to her husband, who was confident that it was not another seizure.

Upon arrival at the ICU, the patient relied on a ventilator with GCS 5 points (E1 V1 M3), and the left pupil was still dilated (d = 4.5 mm) and fixed. The family members decided to give up further treatment right on day 2 after surgery due to financial problems. So, the patient was released from the hospital, and follow-up was not performed, as it would have been unavailable and pointless. She died shortly thereafter because she had still been on a ventilator when the decision to terminate treatment was made.

First, the diagnosis is of particular interest given that the most recent scan with the exception of that performed on the day of surgical intervention was an MRI performed exactly 7 d before. Even if the head injury did not immediately cause hemorrhage, it was a subacute SDH (SSDH) at most with no chance of being a CSDH. Despite the husband’s statement, did the patient have another seizure when she hit the wall? We will never know. Currently, we believe that the essence of CSDH is a fibrous capsule enclosing bloody fluids that requires 3-4 wk to complete encapsulation[2,6]. No previous study has reported such a rapid development of an organized SDH, as noted in our case, and we regret that a pathological examination of the specimen, which could have revealed the structural features of the membranes, was not accomplished in the end. Even if it was subacute, which it was likely not, we cannot explain the almost complete absence of a liquefied hematoma, which conflicts with both our experience and historical reports. Cai et al[7] and Bosma et al[8] reported surgical treatment for several SSDH cases with a transcranial neuroendoscopic approach and traditional burr holes, respectively. These studies reported major liquefaction of the hematomas (subacute), as the liquid was easily drained by regular suction. Making the boldest assumption that CT findings on the day of surgery were due to fresh bleeding secondary to an SSDH, fresh clotted blood derived from recent bleeding within a CSDH or an SSDH usually undergoes rapid liquefaction[2]. However, the hematoma was as solid as organized but with marked differences from fresh clotted blood. Thus, we were put in a predicament because we had to evacuate the hematoma like resecting a convexity meningioma. Youn et al[9] reported a tumor-like presentation of an organized SDH, but the hematoma was chronic. Moreover, the capsular membranes of SSDHs are usually yellowish, whereas those in our case were light in color.

During the initial treatment, oral aspirin was given to the patient who was not a routine user of the drug in the past for ischemic considerations in the nine consecutive days before this unexpected operation. We are not sure whether this treatment played a role in the hemorrhagic event. However, some authors suggest that an elevated risk of SDH (SSDH/CSDH) is related to the use of antiplatelet and/or anticoagulation agents[10,11].

CSDH organization involves the formation of a solid hematoma to replace the primary liquefied bloody contents when the inner and outer membranes completely fuse due to a slowly increased volume of fibrous material by unknown mechanisms[12]. Killeffer et al[13] noted that the liquid characteristic of CSDHs is linked to prevalent local hyperfibrinolytic activities within them, so fibrinolytic abnormalities may be related to the strange organized appearance of the hematoma in our case. However, solid evidence is lacking.

This hematoma did not have characteristics consistent with those of ASDH, CSDH or even SSDH with acute rebleeding. We cautiously present a theory that it may have been a subarachnoid hematoma in which the outer membrane of the hematoma was actually the arachnoid that was thickened for some reason, and what was left on the brain surface was just pia mater (it looked dry, unlike arachnoid covered with CSF). Regardless of the true nature of this hematoma, a large craniotomy was the only correct choice for the patient.

The proportion of cases of CSDH and SSDH that are classified as organized SDHs is low, whereas no cases of ASDH with organizational characteristics have been reported. There is still no feasible explanation of the complete formation of encapsulating membranes around this hematoma in such a short time, and even an educated guess cannot be made. The general principles of neurosurgical practice are not compromised even under peculiar circumstances. More discreetness and more individualized treatment should be administered by neurosurgeons when dealing with SDHs, especially acute or subacute SDHs, as they can be very diverse with regard to their features. We should reconsider and further explore the natural history of SDHs.

We would like to acknowledge professor Xu YH, Chairman, Health Commission of Liaoning Province, and professor Liu RY, Director of Neurosurgery at The First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, for their general support in preparing this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chan SM, Taiwan; Chrastina J, Czech Republic S-Editor: Guo XR L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Guo XR

| 1. | Zacko JC, Harris L, Bullock MR. Youmans neurological surgery. 6th ed. In: Surgical management of traumatic brain injury. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2011: 3424-3452. |

| 2. | Prieto R, Pascual JM, Subhi-Issa I, Yus M. Acute epidural-like appearance of an encapsulated solid non-organized chronic subdural hematoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010;50:990-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tanikawa M, Mase M, Yamada K, Yamashita N, Matsumoto T, Banno T, Miyati T. Surgical treatment of chronic subdural hematoma based on intrahematomal membrane structure on MRI. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001;143:613-618; discussion 618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kuwahara S, Miyake H, Fukuoka M, Koan Y, Ono Y, Moriki A, Mori K, Mokudai T, Uchida Y. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of organized subdural hematoma--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2004;44:376-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rocchi G, Caroli E, Salvati M, Delfini R. Membranectomy in organized chronic subdural hematomas: indications and technical notes. Surg Neurol. 2007;67:374-80; discussion 380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stoodley M, Weir B. Contents of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2000;11:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cai Q, Guo Q, Zhang F, Sun D, Zhang W, Ji B, Chen Z, Mao S. Evacuation of chronic and subacute subdural hematoma via transcranial neuroendoscopic approach. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:385-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bosma JJ, Miles JB, Shaw MD. Spontaneous chronic and subacute subdural haematoma in young adults. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142:1307-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Youn DK, Sohn YK, Park J. Tumor-like presentation of organized chronic subdural hematoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2006;40:199-201. |

| 10. | Kolias AG, Chari A, Santarius T, Hutchinson PJ. Chronic subdural haematoma: modern management and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:570-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rust T, Kiemer N, Erasmus A. Chronic subdural haematomas and anticoagulation or anti-thrombotic therapy. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:823-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Baek HG, Park SH. Craniotomy and Membranectomy for Treatment of Organized Chronic Subdural Hematoma. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2018;14:134-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Killeffer JA, Killeffer FA, Schochet SS. The outer neomembrane of chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2000;11:407-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |