Published online May 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4273

Peer-review started: October 10, 2021

First decision: December 10, 2021

Revised: December 18, 2021

Accepted: March 15, 2022

Article in press: March 15, 2022

Published online: May 6, 2022

Processing time: 202 Days and 0.3 Hours

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) is a mesenchymal tumor with histologic and immunophenotypic characteristics of perivascular epithelioid cells, has a low incidence, and can involve multiple organs. PEComa originating in the liver is extremely rare, with most cases being benign, and only a few cases are malignant. Good outcomes are achieved with radical surgical resection, but there is no effective treatment for some large tumors and specific locations that are contraindicated for surgery.

A 32-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a palpable abdominal mass and progressive deterioration since the previous month. An ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver aspiration biopsy was performed. Postoperative pathological immunohistochemical staining was HMB45, Melan-A, and smooth muscle actin positive. Perivascular epithelioid tumor was diagnosed. The tumor was large and could not be completely resected by surgery. Further digital subtraction angiography revealed a rich tumor blood supply, and interventional embolization followed by surgery was recommended. Finally, the patient underwent transarterial embolization (TAE) combined with sorafenib for four cycles. Angiography reexamination indicated no clear vascular staining of the tumor, and the tumor had shrunk. The patient was followed up for a short period of time, achieved a stable condition, and surgery was recommended.

Adjuvant combination treatment with TAE and sorafenib is safe and feasible as it shrinks the tumor preoperatively and facilitates surgery.

Core Tip: Transarterial embolization in combination with sorafenib is a targeted anti-angiogenic therapy that is widely used in the palliative treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. However, this combination therapy has not been reported in perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). In patients with PEcoma of the liver that cannot be surgically resected or when surgery is contraindicated, this combination of adjuvant therapy is safe and feasible to shrink the tumor and allow the patient to undergo surgery.

- Citation: Li YF, Wang L, Xie YJ. Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(13): 4273-4279

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i13/4273.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4273

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) is a mesenchymal tumor with histologic and immunophenotypic characteristics of perivascular epithelioid cells. It has a low incidence rate and can involve multiple organs. PEComa originating in the liver is extremely rare, with most cases being benign, and only a few cases diagnosed as malignant[1-3]. Good outcomes are achieved with radical surgical resection, but there is no effective treatment for certain large tumors and specific locations that are contraindicated for surgery[3,4]. Targeted anti-angiogenic therapy through transarterial embolization (TAE) in combination with sorafenib is widely used for palliative treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma; however, this combination therapy has not been reported in PEComa. This article presents the therapeutic application and preliminary results of this combination therapy for PEComa in the liver in a patient in whom surgery was contraindicated.

A 32-year-old female patient had palpable abdominal mass and progressive deterioration since the last one month.

The patient had an unremarkable past medical history, no history of recent illness and/or trauma, and was not receiving any medication at the time of referral.

Healthy in the past, denied hepatitis, tuberculosis, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease etc.

The patient stated that no personal or family history of chronic liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma existed.

Specialist abdominal examination: Abdominal distention, liver palpable 10 cm below the costal margin, umbilicus was flat and hard, tenderness was absent, spleen was not palpable below the costal margin, and no positive signs were seen in the rest of the physical examination.

Results of the laboratory evaluation were unremarkable. Serum tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and cancer antigen 19-9) were all within reference ranges, and serology for hepatitis B and C was non-reactive.

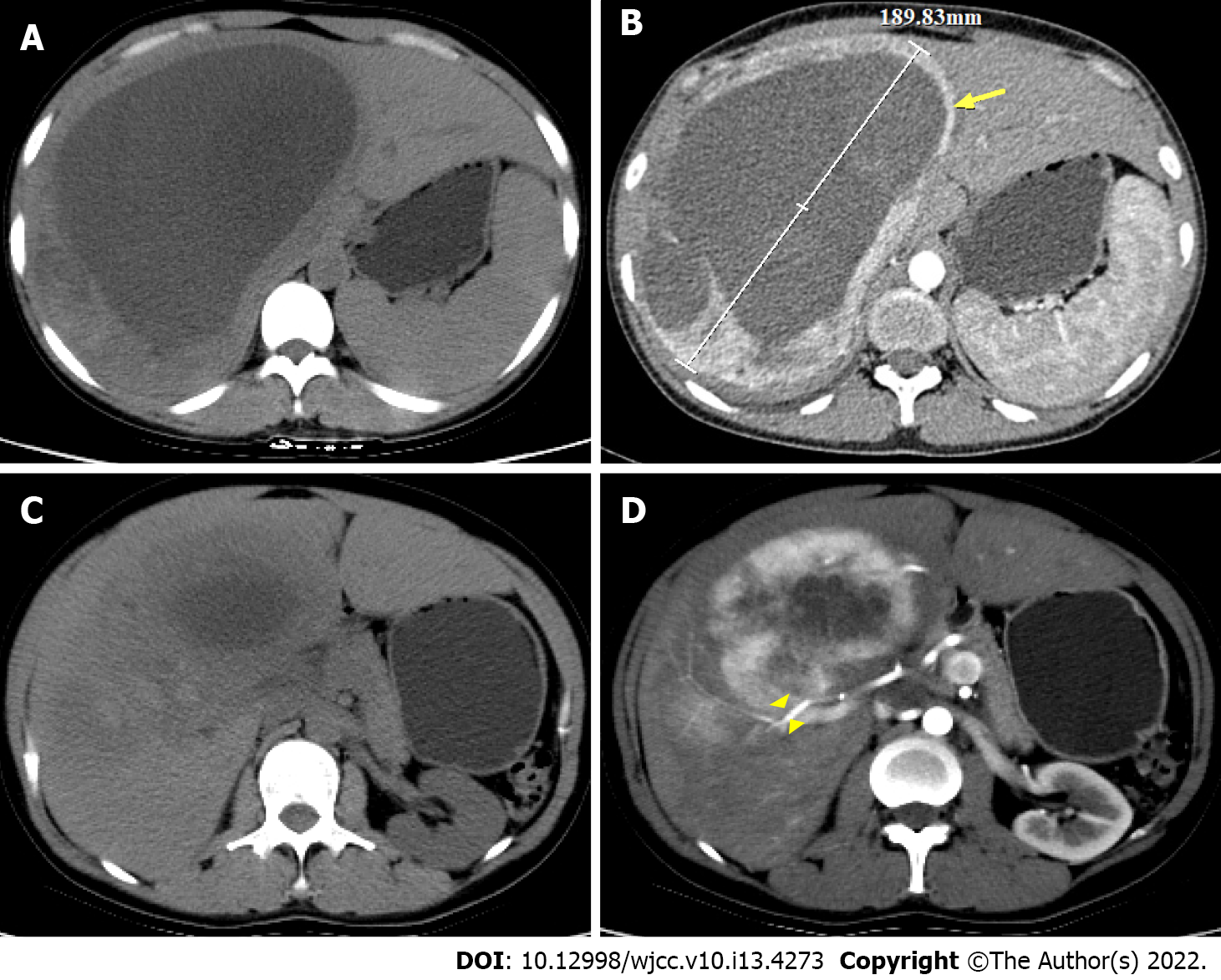

Chest X-ray showed increased markings in both lungs and a small amount of exudate in the lower lobe of the right lung. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a huge oval cystic solid space-occupying lesion (18 cm × 11 cm × 15 cm) in the hepatic S7 and S8 segments. Enhanced scan showed significant non-uniform enhancement with hepatic artery branch penetration; focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver combined with cystic lesion was considered (Figure 1). Ultrasonography results suggested that there were fluid-dominant mixed echogenic lesions in the liver, and the ultrasonography was consistent with a benign lesion enhancement pattern.

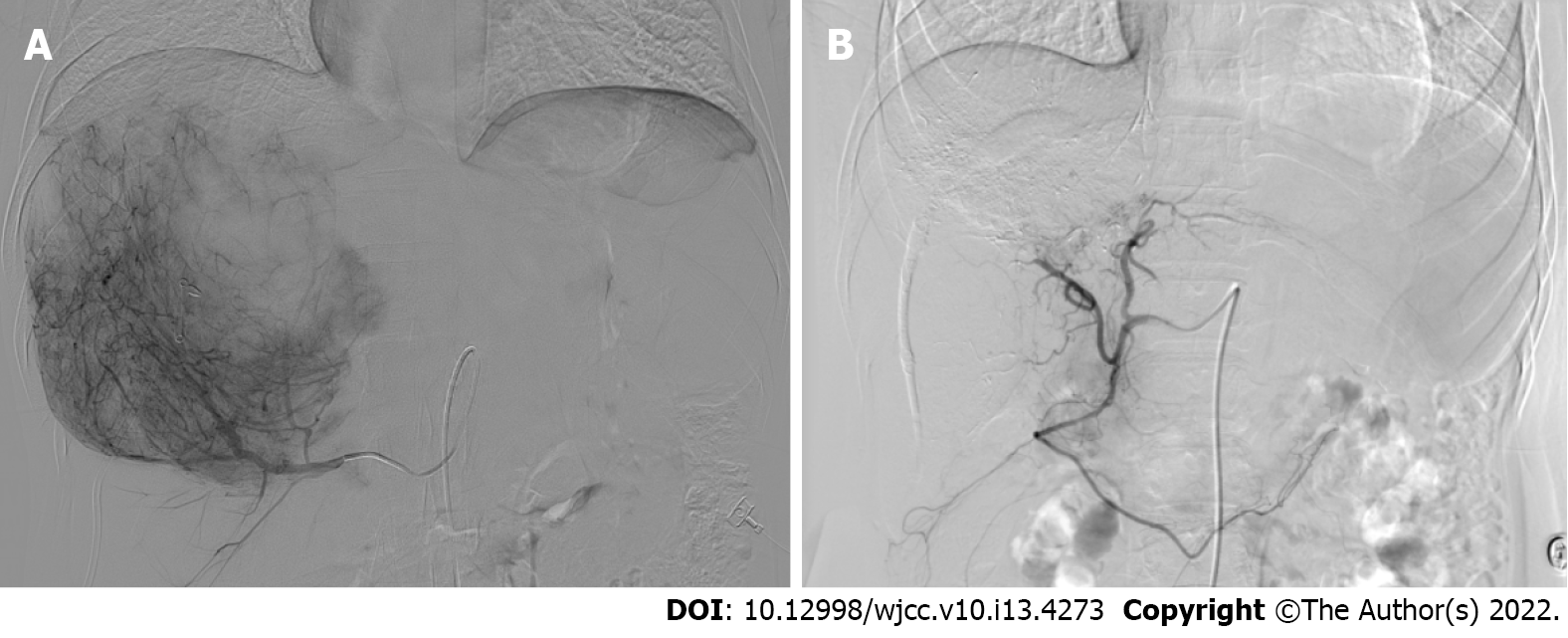

Ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage with simultaneous percutaneous liver biopsy were performed. Postoperative pathology resulted showed immunohistochemical staining: CKp (-), CD163 (+/-), CD68 (+), CK7 (-), Glypican-3 (-), smooth muscle actin (SMA) (+), HMB45 (+), Melan-A (+), CK19 (-), Hepatocyte (-), CEA (-), Ki-67 +2%. Diagnosis: Tumor with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (Figure 2). Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed a rich blood supply to the tumor (Figure 3A).

After multidisciplinary consultation and discussion, the patient was diagnosed with a huge liver tumor that was a potentially malignant progressive PEComa, which was currently too large for complete surgical resection. Digital subtraction DSA showed rich blood supply to the tumor (Figure 3A). Interventional embolization should be the first choice in patients with a rich blood supply tumor. Based on the characteristics of the tumor and lack of sensitive chemotherapeutic drugs, the treatment modality of TAE was chosen instead of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE). The hypoxia caused by TAE could potentially upregulate angiogenic factors and stimulate the proliferation of residual tumor cells, leading to tumor survival and recurrence[12]. Thus, a treatment plan involving TAE combined with sorafenib was planned. The embolic agents used were 10 mL of iodine oil + 350-560 μm PVA embolic pellets to ensure the adequacy of embolization. Four TAEs were performed from January to August 2019, during which treatment was combined with sorafenib (0.4 g orally bid, subsequently changed to 0.2 g orally qd due to the development of diarrhea and hand-foot syndrome). The tumor shrank after treatment, and the tumor was evaluated according to RECIST1.1 to be partially responsive. The lesion shrank on repeat enhanced CT in August 2019 (Figure 4). DSA was repeated, and no clear tumor staining was observed (Figure 3B). TAE treatment was suspended, and surgery was recommended, which the patient declined. The patient discontinued treatment with sorafenib on her own. Six months later, repeat abdominal enhancement CT showed no significant tumor growth (Figure 5).

The patient was treated with four sessions of TAE combined with sorafenib therapy, which led to significant lesion reduction. Six months after cessation of treatment, an enhanced CT (Figure 5) review showed tumor shrinkage and disappearance of the cyst, and elective surgery was recommended.

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) are a rare group of tumors of mesenchymal origin, defined in the 2002 edition of the World Health Organization Pathology Classification as "a mesenchymal tumor with histologic and immunophenotypic features of perivascular epithelioid cells."[1] The incidence of PEComa is low, and PEComas mostly occur in the uterus, followed by the kidneys, bladder, prostate, lung, pancreas and liver. Primary hepatic PEComa is rare[2], with a higher incidence in women than in men, the lesions mainly accumulate in the right lobe, the pathogenesis remains unclear, and the number of available cases does not accurately reflect the incidence of PEComas in the liver[2,4].

Liver PEComas lack specific clinical symptoms and are mostly detected during routine physical examinations. They mainly present with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, bloating, abdominal discomfort, and vomiting. The appearance of symptoms may be related to an increase in the tumor size. Local compression or liver capsule traction. A small number of patients present with painless masses[2,4].

Laboratory tests for hepatic PEComas are non-specific; there are no uniform criteria for imaging diagnosis, and preoperative imaging diagnosis is very difficult. Most patients are misdiagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, hemangioma, or hepatic adenoma. A hepatic PEComa presents on CT or MRI as well-defined with early enhancement in the arterial phase and non-uniform enhancement in the venous and delayed phases. Malformed vessels are usually present, and cystic lesions are extremely rare[3,5,6]. Our patient had no specific clinical symptoms or laboratory test results other than an abdominal mass, which showed non-uniform enhancement on imaging.

Biopsy is commonly used for the preoperative diagnosis of PEComa[3], where tumor cells are arranged around blood vessels and exhibit a pleomorphic nature with three main types of cells: Epithelioid, spindle, and adipocytes – which have different degrees of differentiation and are difficult to diagnose histologically. Immunohistochemistry is currently the only clinical method to confirm the diagnosis, with HMB-45, Melan-A, and SMA as specific immunomarkers[2,7,8]. HMB-45 is associated with poor prognosis in more than 92% of livers with positive PEComa markers[3,9]. This patient matched the pathological diagnosis described above.

The vast majority of hepatic PEComas are benign, with 4%-10% of reported cases being malignant[10]. In malignant lesions, the tumor size is greater than 5 cm in diameter and shows marked nuclear heterogeneity, pleomorphism, high nuclear division index, necrosis, and marginal infiltration, some of which are known to recur or metastasize[3,10]. This patient had no significant malignant tendency with a tumor larger than 5 cm, which rapidly increased in size over a short period of time and had to be treated aggressively. Complete surgical resection of the lesion is the main treatment modality, but there is a lack of effective treatment for some patients with PEcomas of the liver that are large and in such a location where they cannot be surgically resected or surgery is contraindicated. At present, there is a lack of effective measures, and the results of chemotherapy and radiotherapy are uncertain. New targeted treatment with an mTOR inhibitor (sirolimus) has achieved some efficacy in clinical trials but has not been widely used[2,4,11].

Targeted anti-angiogenic therapy with TAE in combination with sorafenib is widely used in the palliative treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. The tumor was huge, with rapid short-term growth, marked malignant tendency, and significant contraindications to surgery. Thus, TAE combined with sorafenib was chosen for the following reasons. First, DSA of the liver showed an abundant blood supply for arterial administration. The tumor lacked sensitive chemotherapeutic agents; therefore, TAE replaced TACE. Second, TAE can cause ischemia and necrosis in the tumor tissue, but the resultant hypoxia could upregulate angiogenic factors and stimulate the proliferation of residual tumor cells, leading to tumor survival and recurrence[12]. Sorafenib was selected for its dual anti-angiogenic and anti-proliferative activity, as well as the fact that a previous case of malignant liver PEcoma that was misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma was treated with oral sorafenib for 10 years and demonstrated some therapeutic value[13]. This patient was treated with four sessions of TAE combined with sorafenib for significant lesion reduction. Surgery was suggested after the follow-up.

PEComa of the liver is a rare disease with a high likelihood of misdiagnosis and needs to be confirmed by pathology and immunohistochemistry; surgery remains the primary treatment. However, TAE combined with anti-angiogenic targeted therapy may be an effective treatment in some cases involving large tumor size and a location contraindicated for surgery.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Integrative and complementary medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen S, Japan; Yang M, United States S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Folpe AL. Neoplasms with perivascular epitheloid cell differentiation (PEComas). In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Epstein J et al. (eds) Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone Series: WHO Classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002: 221–222. |

| 2. | Ma Y, Huang P, Gao H, Zhai W. Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): analyses of 13 cases and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11:2759-2767. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni G, Bonetti F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:119-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Klompenhouwer AJ, Verver D, Janki S, Bramer WM, Doukas M, Dwarkasing RS, de Man RA, IJzermans JNM. Management of hepatic angiomyolipoma: A systematic review. Liver Int. 2017;37:1272-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | O'Malley ME, Chawla TP, Lavelle LP, Cleary S, Fischer S. Primary perivascular epithelioid cell tumors of the liver: CT/MRI findings and clinical outcomes. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42:1705-1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang X, Li A, Wu M. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: clinical, imaging and pathological features in 178 cases. Med Oncol. 2013;30:416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. PEComa: what do we know so far? Histopathology. 2006;48:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Folpe AL, Kwiatkowski DJ. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms: pathology and pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Skaret MM, Vicente DA, Deising AC. An Enlarging Hepatic Mass of Unknown Etiology. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:e14-e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wagner AJ, Malinowska-Kolodziej I, Morgan JA, Qin W, Fletcher CD, Vena N, Ligon AH, Antonescu CR, Ramaiya NH, Demetri GD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Maki RG. Clinical activity of mTOR inhibition with sirolimus in malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: targeting the pathogenic activation of mTORC1 in tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:835-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sergio A, Cristofori C, Cardin R, Pivetta G, Ragazzi R, Baldan A, Girardi L, Cillo U, Burra P, Giacomin A, Farinati F. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): the role of angiogenesis and invasiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:914-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 397] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Britt A, Mohyuddin GR, Al-Rajabi R. Maintenance of stable disease in metastatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the liver with single-agent sorafenib. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |