Published online May 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4171

Peer-review started: August 24, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 7, 2022

Accepted: March 16, 2022

Article in press: March 16, 2022

Published online: May 6, 2022

Processing time: 248 Days and 15.5 Hours

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) is a rare X-linked genetic disease. It mainly manifests as skin lesions and causes problems in the eyes, teeth, bones, and central nervous system. Of the various ocular manifestations, the most severe with difficult recovery is retinal detachment (RD). Here, we report an unusual case of bilateral asymmetrical RD.

We present the case of an 11-year-old Chinese girl with IP who complained of sudden blurring of vision in the left eye. At that time, she had been blind in her right eye for 4 years. RD with traction was observed in both eyes. A massive retinal proliferative membrane, exudation, and hemorrhage were seen in the left eye. We performed vitrectomy in her left eye. Her visual acuity recovered to 20/50, and her retina had flattened within 2 d after surgery. During the 3-mo follow-up, we performed retinal laser treatment of the non-perfused retinal area in her left eye. Eventually, her visual acuity returned to 20/32, and no new retinal abnormalities developed.

In patients with IP with fundal abnormalities in one eye, it is important to focus on the rate of fundal change in the other eye. RD in its early stages can be effectively treated with timely vitrectomy and laser photocoagulation.

Core Tip: Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) is a rare X-linked genetic disorder. It occurs due to a mutation in the IKBKG gene. We report an unusual IP case who presented with asymmetrical retinal detachment in both eyes. Genome sequencing revealed a rare mutation previously mentioned only once. Following prompt vitrectomy of her left eye, her symptoms significantly improved. This case reminds us to pay more attention to potential abnormal changes in the other eye of patients with monocular retinal abnormalities.

- Citation: Cai YR, Liang Y, Zhong X. Late contralateral recurrence of retinal detachment in incontinentia pigmenti: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(13): 4171-4176

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i13/4171.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i13.4171

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP), also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is a rare X-linked genetic disorder (OMIM: 308,300). It occurs due to a mutation in the IKBKG gene, which is located on the X-chromosome at position q28. The prevalence of IP may vary according to sex and geographical location. It usually occurs in female individuals, as it is typically lethal at the embryonic stage in males, owing to X inactivation mosaicism, although the proportion of male patients reported to survive past birth in East Asia was higher than that in other areas[1]. The incidence of IP is 0.7 per 100000 individuals[2].

Skin lesions are the main presentation in patients with IP. Patients usually exhibit stereotypical skin lesions during infancy and early childhood. These first present as a blistering maculopapular lesion that develops into a whorled pigmented lesion in four stages[3]. IP is usually accompanied by lesions in ectodermal tissues including the skin, eyes, teeth, bones, and central nervous system. Manifestations in the central nervous system can lead to severe disability[4].

The ocular manifestations in patients with IP are diverse and involve the retina, lens, vitreous humor, optic nerve, and other structures; 7%-23% of patients experience blindness in at least one eye, mainly due to retinal vascular abnormalities, retinal pigment epithelial lesions, and retinal detachment (RD)[5]. Here, we present an atypical case of both eyes presenting sequentially with tractional RD in a girl with IP, as shown by an unreported code-shifting variant in East Asian populations.

An 11-year-old Chinese girl presented to our outpatient clinic with sudden blurred vision in the left eye that occurred 7 d before her visit.

Four days before presentation at our hospital, the patient visited a local hospital with the same complaint. She was diagnosed with bilateral RD and advised to visit a higher-level hospital. The patient had no other discomfort except for blurred vision.

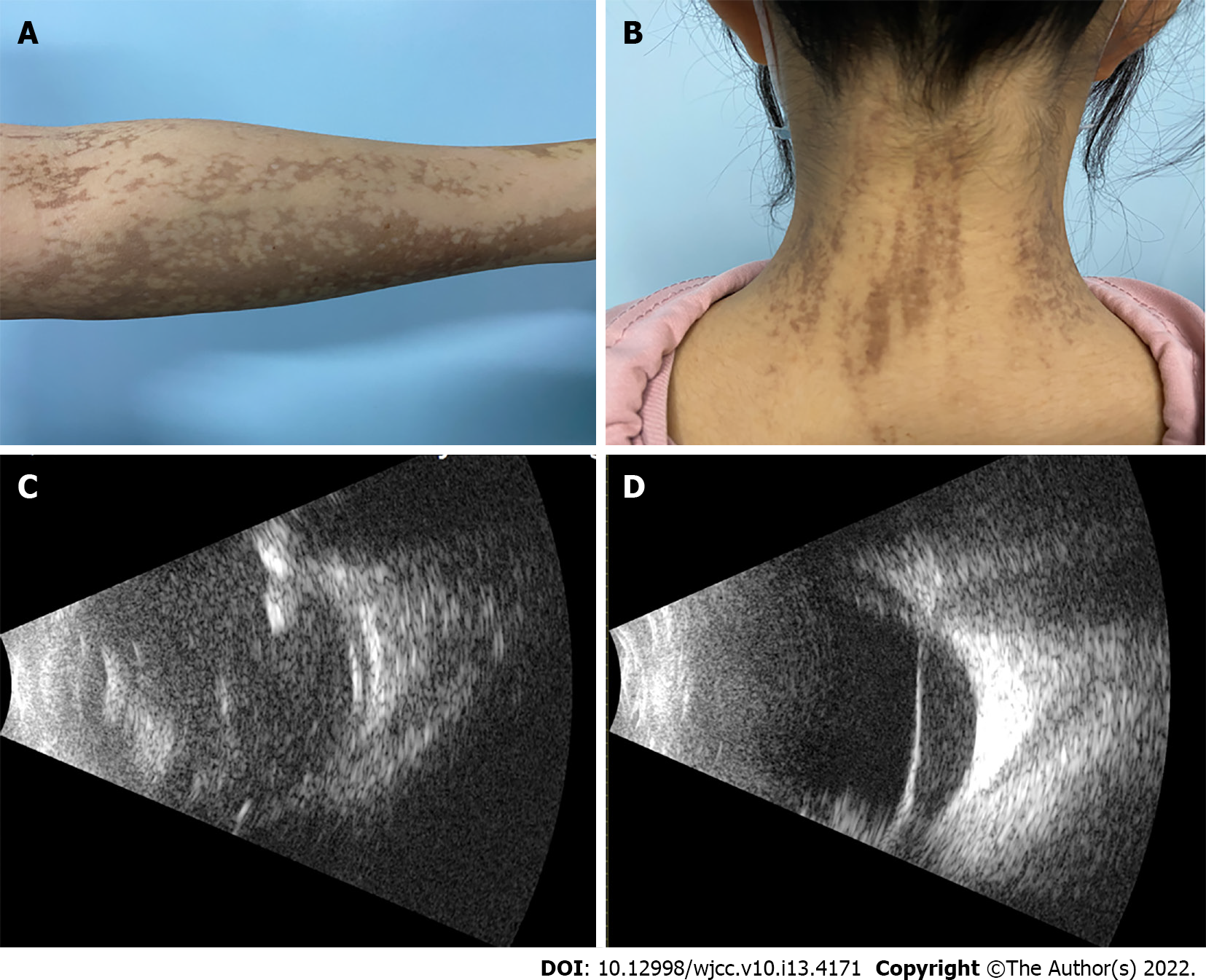

She had experienced blisters of varying dimensions on her trunk and limbs from the first postnatal week, followed by rupture and crusting of the blisters and streaks of pigmentation on the extremities (Figure 1A) and back of her neck (Figure 1B). In infancy, the patient visited a dermatologist and was diagnosed with IP. Her right eye was previously diagnosed with RD in our hospital in 2017, but the treatment window was missed.

Tracing her family history, her parents and her younger brother had no history of skin or ocular disease and were all born at full term.

At initial examination, her visual acuity was assessed as no perception of light in the right eye and able to count fingers with the left eye, with no improvement with correction. Intraocular pressure in both eyes was 16 mmHg. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior chamber revealed a cloudy lens in the right eye, and vitreous turbidity, elevated retinal folds, massive proliferation of membranes, exudates, and hemorrhages in the left eye.

Genome sequencing revealed a heterozygous shift in the IKBKG gene in the patient, a rare shift mutation in exon 5 (c.519-3_519dup:p?) at chrX: 153,788,619-153,788,622.

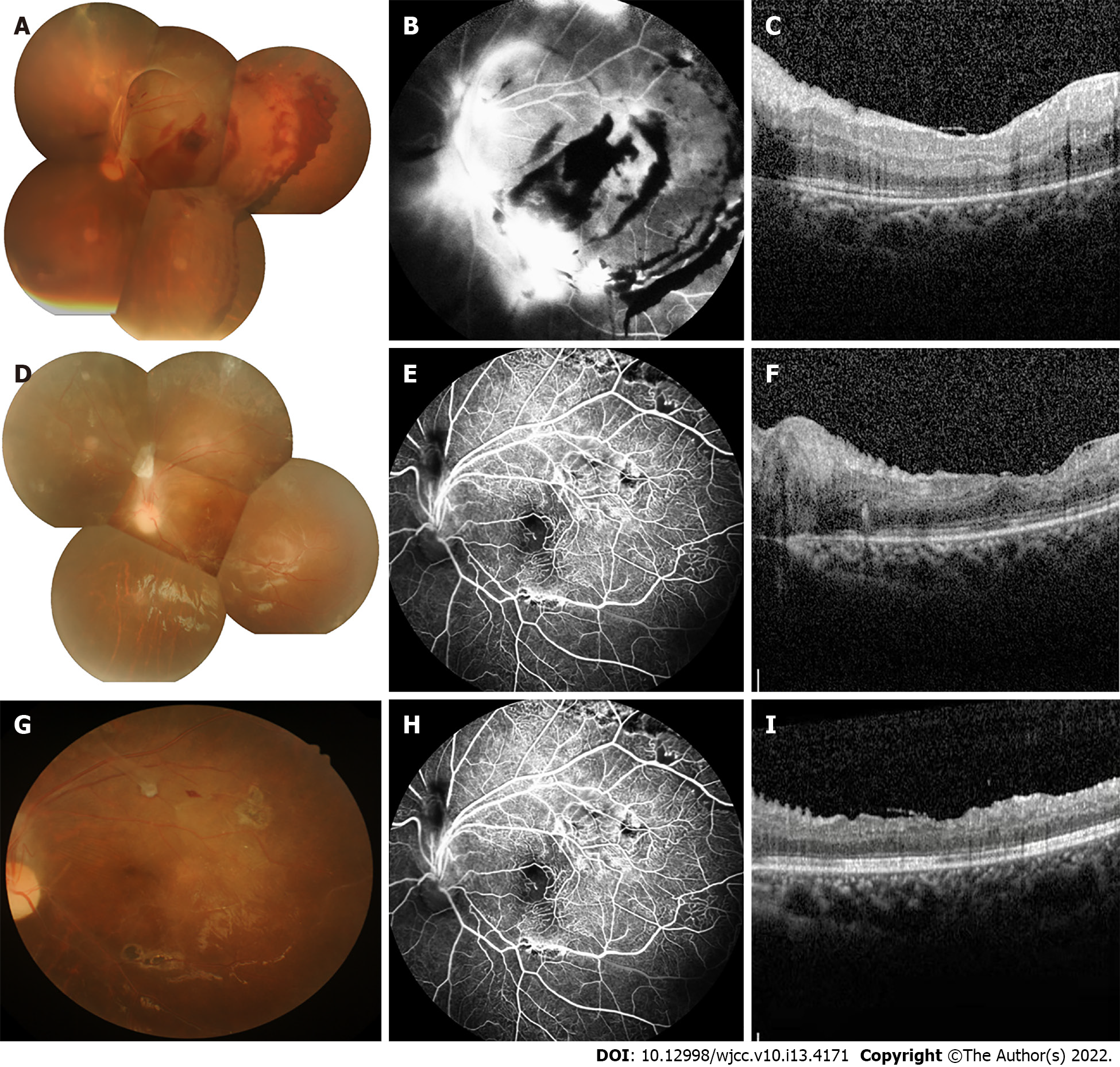

Ultrasound of the eye revealed clouded refractive media and extensive RD in the right eye (Figure 1C) and suspected RD in the left eye (Figure 1D). Dilated fundus examination revealed a patchy macula-colored exudate and hemorrhage with greenish-gray bulging of the peripheral retina in the left eye (Figure 2A). Fundus fluorescence angiography (FFA) revealed temporal and inferior temporal vascular occlusion, and retinal vascular endings and optic disc surface capillaries were dilated with enhanced permeability. An area without perfusion was observed in the left eye (Figure 2B).

A diagnosis of bilateral RD related to IP was confirmed based on the medical history, clinical signs, examinations, and intraoperative findings.

We promptly performed vitrectomy, combined with intravitreal spherical gas injection in the left eye. In addition, a laser was used in the non-perfused area.

Two days after surgery, the patient’s symptoms, including visual acuity, RD, and hemorrhages significantly improved. Her visual acuity improved to 20/50, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) examination revealed retinal flattening (Figure 2C). After 1 mo, FFA revealed a non-perfused zone in the retinal periphery (Figure 2E). Fundus photography showed a resorbed hemorrhage and grayish exudate (Figure 2D). Therefore, we performed supplementary laser photocoagulation in the peripheral zone of the retina. Four months after surgery, the patient visited our hospital for further testing. Her visual acuity had improved to 20/32, and FFA showed lattice-like non-perfused areas in the peripheral retina. Macular OCT revealed retinal edema and exudation (Figure 2I) and non-perfused areas with hyperfluorescence, representing neovascularization and fluorescein infiltration, visible in the upper retina on FFA (Figure 2H). Additional retinal laser photocoagulation was performed in the left eye. During the short follow-up, the patient’s vison recovered well, the retina had flattened, and no new fundus lesions were observed. Lifelong ongoing follow-up is planned.

IP is a rare X-linked genetic skin disease that also causes neurological, ophthalmological, hair, nail, and teeth problems. Nearly 100% of IP patients have skin lesions, 30% have neurologic presentations, 54%-80% have dental problems, and 25%-77% have ocular diseases[1]. Although ophthalmological lesions are not the most common, ocular involvement persists in patients throughout their lifetime and affects their quality of life. The most characteristic and most serious injuries are retinal injuries. RD is often difficult to repair surgically and is the leading cause of blindness. Current reports on the ocular condition of patients with IP are mostly of infants who developed retinal changes, with few reports of patients who developed bilateral RD. In this case, the girl belonged to a rural area, and her eye examinations were conducted only intermittently after birth, owing to geographic and economic considerations. However, she did not experience any eye discomfort until she was 7 years old. She presented to a hospital with a 7-d history of vision loss. The right eye was lost to surgery at that time; fortunately, the left eye still had a chance to recover good eyesight.

IP is a genetic disease associated with many lesions at various sites, especially in the eyes. O'Doherty et al[6] believed that ocular changes can be divided into four stages. The most severe outcome is RD. It is important to establish early treatment to prevent RD. Therefore, most current studies have been conducted on infants. Several studies have suggested that the prevention of RD is the most important aspect of ocular pathology in patients with IP. Early laser treatment is required when retinal neovascularization and areas of ischemia are present[7]. The incidence of RD is approximately 20% and the functional prognosis is extremely poor[1,8]. RD can be treated with vitrectomy or scleral buckling. For advanced lesions, it is difficult to achieve a good outcome even with surgical treatment[9]. Our patient presented with RD; therefore, we performed vitrectomy combined with laser photocoagulation on her left eye with localized RD. The outcome, including visual acuity and fundus examination findings, was acceptable. This might be related to the fact that the patient visited the clinic at the very first appearance of eye symptoms.

No standard recommendations for ophthalmic screening or IP follow-up are currently available. Holmstrom and Thoren proposed that examinations of the eyes should be performed as soon as possible after birth, at least once a month for 3-4 mo, and the frequency of examinations should be increased in children with ocular pathologies. If no abnormalities are found by the age of 3 years, follow-up may be discontinued. Our patient was from a rural area where financial factors and poor medical provision made it difficult for her to have regular scheduled follow-up visits. Due to the lack of previous examination data, it is difficult to determine whether retinal abnormalities were present before 3 years of age. As eye abnormalities persist throughout the life of patients with IP, those who develop retinal abnormalities are followed-up for life. In addition, for patients with retinal abnormalities in one eye, we should increase the frequency of follow-up and pay more attention to fundus changes in the other unaffected eye.

Exons 4 to 10 of the IKBKG gene are a mutational hot spot, with deletions being particularly common[10]. In the genomic testing of our patient's peripheral blood sample, there was a shift variant in exon 5 of IKBKG. A mutation in the IKBKG gene in intron 4 has been reported in one patient[11]. However, the patient reported previously only had central nervous system, hair, and dental issues. Our patient with IP is the first case with this mutation and ocular disease. This genetic abnormality was probably the cause of the disease in the girl. However, the significance of this variant cannot be confirmed because it has been rarely reported to date.

Asymmetric retinal changes in both eyes are typical ocular abnormalities in patients with IP. Surgery combined with laser therapy is an effective treatment for patients who develop early RD. This case highlights that, in patients who present with retinal abnormalities in one eye, more attention should be paid to potential abnormal changes in the other eye. In addition, genetic testing should be performed in patients with IP to learn more about the association of mutations with disease-related changes.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Ophthalmology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Damiani G, Italy;

| 1. | Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia Pigmenti: A Comprehensive Review and Update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:650-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cammarata-Scalisi F, Fusco F, Ursini MV. Incontinentia Pigmenti. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:273-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Landy SJ, Donnai D. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome). J Med Genet. 1993;30:53-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia Pigmenti: A Summary Review of This Rare Ectodermal Dysplasia With Neurologic Manifestations, Including Treatment Protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, Maria FD, Campos CW, Travi GM, Freitas AM, Maahs MA, Zen PR, Fiegenbaum M, Almeida ST, Bonamigo RR, Bau AE. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:26-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | O'Doherty M, Mc Creery K, Green AJ, Tuwir I, Brosnahan D. Incontinentia pigmenti--ophthalmological observation of a series of cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Michel S, Reynaud C, Daruich A, Hadj-Rabia S, Bremond-Gignac D, Bodemer C, Robert MP. Early management of sight threatening retinopathy in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen CJ, Han IC, Tian J, Muñoz B, Goldberg MF. Extended Follow-up of Treated and Untreated Retinopathy in Incontinentia Pigmenti: Analysis of Peripheral Vascular Changes and Incidence of Retinal Detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:542-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wald KJ, Mehta MC, Katsumi O, Sabates NR, Hirose T. Retinal detachments in incontinentia pigmenti. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:614-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hsiao PF, Lin SP, Chiang SS, Wu YH, Chen HC, Lin YC. NEMO gene mutations in Chinese patients with incontinentia pigmenti. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109:192-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Conte MI, Pescatore A, Paciolla M, Esposito E, Miano MG, Lioi MB, McAleer MA, Giardino G, Pignata C, Irvine AD, Scheuerle AE, Royer G, Hadj-Rabia S, Bodemer C, Bonnefont JP, Munnich A, Smahi A, Steffann J, Fusco F, Ursini MV. Insight into IKBKG/NEMO locus: report of new mutations and complex genomic rearrangements leading to incontinentia pigmenti disease. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:165-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |