Published online Apr 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i12.3739

Peer-review started: October 1, 2021

First decision: December 10, 2021

Revised: December 24, 2021

Accepted: March 6, 2022

Article in press: March 6, 2022

Published online: April 26, 2022

Processing time: 201 Days and 22 Hours

Ovarian cancer is one of the three most common malignant tumors of the female reproductive tract and ranks first in terms of mortality among gynecological tumors. Epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) is the most common ovarian malignancy, accounting for 90% of all primary ovarian tumors. The clinical value of cytoreductive surgery in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent EOC remains largely unclear.

To evaluate the feasibility of secondary cytoreductive surgery for treating platinum-resistant recurrent EOC.

This was a retrospective study of the clinical data of patients with platinum-resistant EOC admitted to the Cancer Hospital of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences between September 2012 and June 2018. Patient baseline data were obtained from clinical records. Routine follow-up of disease pro

A total of 38 patients were included. R0 resection was achieved in 25 (65.8%) patients and R1/2 in 13 (34.2%). Twenty-five (65.8%) patients required organ resection. Nine (23.7%) patients had operative complications, 36 (94.7%) received chemotherapy, and five (13.2%) had targeted therapy. Median PFS and OS were 10 (95%CI: 8.27-11.73) months and 28 (95%CI: 12.75-43.25) months, respectively; median CFI was 9 (95%CI: 8.06-9.94) months. R0 resection and postoperative chemotherapy significantly prolonged PFS and OS (all P < 0.05), and R0 resection also significantly prolonged CFI (P < 0.05). Grade ≥ 3 complications were observed, including rectovaginal fistula (n = 1), intestinal and urinary fistulas (n = 1), and renal failure-associated death (n = 1). Except for the patient who died after surgery, all other patients with complications were successfully managed. Two patients developed intestinal obstruction and showed improvement after conservative treatment.

Secondary cytoreductive surgery is feasible for treating platinum-resistant recurrent EOC. These findings provide important references for the selection of clinical therapeutic regimens.

Core Tip: This retrospective study examined 38 patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC). R0 resection was achieved in 25 (65.8%) and R1/2 in 13 (34.2%). Twenty-five (65.8%) patients required organ resection. Nine (23.7%) patients had operative complications, 36 (94.7%) received chemotherapy, and five (13.2%) had targeted therapy. Median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 10 and 28 mo, respectively; median chemotherapy-free interval (CFI) was 9 mo. R0 resection and postoperative chemotherapy significantly prolonged PFS and OS, and R0 resection also significantly prolonged CFI. Overall, these findings indicated secondary cytoreductive surgery is feasible for the treatment of platinum-resistant recurrent EOC.

- Citation: Zhao LQ, Gao W, Zhang P, Zhang YL, Fang CY, Shou HF. Surgery in platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(12): 3739-3753

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i12/3739.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i12.3739

Ovarian cancer is one of the three most common malignant tumors of the female reproductive tract and ranks first in terms of mortality among gynecological tumors[1]. Worldwide, there are more than 200000 new cases each year, i.e., approximately 6.6 per 100000 women[2]. In China, ovarian cancer incidence is 5.3 per 100000[3]. Epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) is the most common ovarian malignancy, accounting for 90% of all primary ovarian tumors[4]. With advances in surgical treatments and the development of chemotherapeutic drugs and targeted therapies (e.g., PARP inhibitors), the prognosis of EOC patients has been greatly improved; however, five-year survival remains very low, predominantly due to cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy. The overall five-year survival rate of EOC patients in the United States is about 49%, but only 17% in cases with advanced disease[5-7]. The latest Chinese survey in 2014 showed an average five-year survival rate for ovarian cancer of 38.9%[3,8].

The response rate obtained after platinum-based chemotherapy is about 80% in the adjuvant setting but is reduced to approximately 20% in recurrent EOC[4,9,10]. In addition, newly available PARP inhibitors improve the prognosis of patients with platinum-sensitive EOC but show low efficacy in platinum-resistant EOC[11,12]. Thus, improving the management of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer is extremely important in improving patient prognosis. The main treatment goals in recurrent EOC include symptom relief, improved quality of life, and prolonged survival. According to the latest NCCN guidelines for recurrent EOC, alternative treatments for platinum-resistant recurrent EOC patients mainly include “participation in clinical trials, supportive care, chemotherapeutic regimens (non-platinum monotherapy), or observation (category 2B)”[10]. For the treatment of cisplatin-resistant recurrent EOC, the traditional main approach is administering non-platinum chemotherapeutic drugs with or without bevacizumab, but its efficacy is poor, with an increase in progression-free survival of only about 3 mo[13,14]. Other chemotherapeutic drugs show objective response rates of 19%-27%[10]. In patients with platinum-resistant EOC, median overall survival (OS) is approximately 1 year[10,15].

For platinum non-resistant patients, the NCCN guidelines suggest that secondary cytoreductive surgery could be considered[10]. However, in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent EOC, further studies are needed to verify the feasibility of cytoreductive surgery in prolonging survival. Indeed, the value of cytoreductive surgery in such patients remains controversial[16,17]. Nevertheless, recent studies suggested a survival benefit in selected patients, especially those with minimal residual disease after surgery[17-24]. This finding was also supported by a meta-analysis[25].

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of secondary cytoreductive surgery for the treatment of platinum-resistant recurrent EOC. The results could provide a promising option for improving the prognosis of such patients.

It was a retrospective study of the clinical data of patients with platinum-resistant EOC admitted to the Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Cancer Hospital of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Zhejiang, China) between September 2012 and June 2018. The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital. The study has obtained informed consent for all individual participants that appear in this manuscript.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Pathologically confirmed recurrent EOC, defined as clinical relapse with objective radiological disease progression based on the modified RECIST version 1.1[26], with or without previous chemotherapy[10]; (2) Platinum-resistant recurrent EOC, i.e., failure to control condition after chemotherapy with platinum drugs or recurrence within 6 mo after discontinuation of chemotherapy (drug resistance after the initial administration of platinum drugs was defined as primary drug resistance; otherwise, secondary drug resistance was considered)[10,27]; (3) Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent EOC in our hospital; and (4) Complete medical records. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Concurrent malignant tumor; or (2) 5-year history of another primary malignant tumor, except for carcinoma in situ.

The patient underwent maximum cytoreductive surgery, and multiple organs were removed if necessary. Postoperative chemotherapy was administered. All surgeries were completed by the same team consisting of chief physicians with > 20 years of experience. There is no standard surgical procedure for secondary surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer. Therefore, the operation depended on the involved organs. Recurrence locations (e.g., abdominopelvic cavity) were examined, with or without organ resection; most importantly, the presence or absence of residual lesions was recorded.

The chemotherapeutic regimen was platinum combined with liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, docetaxel, or etoposide, as suggested by the NCCN guidelines that were current at the time of patient treatment (i.e., the 2012-2018 NCCN guidelines).

Follow-up ended on April 15, 2019, and was performed routinely at the outpatient clinic or by telephone. All data were extracted from medical charts. Routine follow-up of disease progression was performed as follows. CA125 assessment and physical examination were performed every 3 wk during treatment, including gynecological examination. Imaging assessment was carried out every 12 wk by B-mode ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). At the end of treatment, comprehensive reexamination, including CA125 detection, gynecological examination, and imaging, was performed. Imaging was performed to assess disease progression and recurrence, recurrence sites, lesion location, presence or absence of ascites, etc. Given that ovarian cancer recurrence may occur in the abdominopelvic cavity, chest, brain, and other locations, imaging examinations were performed for all these suspicious locations, mainly by B-mode ultrasound, but also by CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography. After treatment, follow-up was performed every 3 mo within 2 years and every 6 mo after that. CA125 detection, gynecological examination, and imaging were performed in post-treatment follow-ups. Progression-free survival (PFS) was determined as the time between the cytoreductive surgery and objective radiological disease progression based on the modified RECIST 1.1[26] or death. OS was determined as the time from the cytoreductive surgery to death.

Patient baseline data were obtained from clinical records, including age, pathological type (high-grade serous carcinoma, endometrioid carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, and mixed type), pathological classification (highly, moderately, and poorly differentiated), previous surgery (residual lesions of the first surgery, International federation of gynecology and obstetrics (FIGO) staging, and the number of previous surgeries), previous chemotherapy (neoadjuvant chemotherapy or not, the total number of previous chemotherapies, and remission time conferred by chemotherapy before drug-resistance necessitating surgery), and type of drug resistance (primary or secondary platinum resistance). In addition, relevant surgical data were also documented, including the time from disease onset to this surgery, preoperative Eastern collaborative oncology group (ECOG) score, location of recurrent lesions, and surgical resection outcome (R0, no macroscopic residual lesion; R1, residual lesion ≤ 1 cm; R2, > 1 cm), intraoperative organ resection or not, intraoperative bleeding amount, perioperative complications, total number of postoperative chemotherapies, postoperative administration of targeted drugs or not, and postoperative hospital stay.

The primary outcome was PFS. Secondary outcomes included: (1) Postoperative OS; (2) chemotherapy-free interval (CFI) after surgery and first-line chemotherapy; and (3) perioperative complications, including their severity levels (severity classification of surgical complications of the MSKCC[28]) and treatment conditions.

At least two senior gynecological oncologists assessed postoperative progression. In case of disagreement, the department conducted discussions until consensus. At each follow-up reexamination, comprehensive assessments were performed: CA125 Level determination, gynecological examination, and imaging.

All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous data with normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD, and those with skewed distribution as median (range). Categorical data were presented as frequency (percentage). Univariable Cox regression analysis was performed for PFS, OS, and CFI. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted and analyzed by the log-rank test. Multivariable models were unstable because of the small sample size, and such analyses could not be performed in a reliable manner. Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 38 patients were included. Their characteristics are presented in Table 1. The resection type at the initial surgery was R0 in 20 (52.6%) patients, R1 in 10 (26.3%), and R2 in 8 (21.1%). Among these patients, 16 (42.1%) had recurrence within 3 mo of the initial treatment, and 22 (57.9%) between 3 and 6 mo. Twenty-seven (71.1%) patients had secondary platinum resistance, while 11 (28.9%) had primary resistance.

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 38) |

| Age, n (%) | |

| < 50 yrs | 18 (47.4) |

| ≥ 50 yrs | 20 (52.6) |

| Pathological type, n (%) | |

| High-grade serous carcinoma | 26 (68.4) |

| Endometrioid carcinoma | 5 (13.2) |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 5 (13.2) |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 1 (2.6) |

| Mixed type | 1 (2.6) |

| Pathological classification, n (%) | |

| Highly differentiated | 3 (7.9) |

| Moderately differentiated | 3 (7.9) |

| Poorly differentiated | 32 (84.2) |

| Number of previous surgery, n (%) | |

| 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| 1 | 32 (84.2) |

| 2 | 4 (10.6) |

| 3 | 1 (2.6) |

| Number of previous chemotherapy lines, n (%) | |

| 1 | 24 (63.1) |

| 2 | 8 (21.1) |

| ≥ 3 | 6 (15.8) |

| FIGO staging of the first surgery, n (%) | |

| I | 2 (5.3) |

| II | 12 (31.5) |

| III | 22 (57.9) |

| IV | 2 (5.3) |

| Residual lesions of the first surgery, n (%) | |

| R0 | 20 (52.6) |

| R1 | 10 (26.3) |

| R2 | 8 (21.1) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 9 (23.7) |

| Remission time of chemotherapy before this secondary surgery, n (%) | |

| ≤ 3 mo | 16 (42.1) |

| 3-6 mo | 22 (57.9) |

| Type of platinum resistance, n (%) | |

| Secondary | 27 (71.1) |

| Primary | 11 (28.9) |

Table 2 presents the characteristics of cytoreductive surgeries. Most patients (33/38, 86.8%) had an ECOG of 0-1. The recurrent lesions were in the pelvic cavity in 7 (18.4%) patients, in the abdominopelvic cavity in 16 (42.1%), and in the abdominopelvic cavity and retroperitoneum in 15 (39.5%). R0 resection was achieved in 25 (65.8%) patients and R1/2 in 13 (34.2%). Twenty-five (65.8%) cases required organ resection. Nine (23.7%) patients showed operative complications, 36 (94.7%) underwent chemotherapy, and five (13.2%) received targeted therapy. Most patients (24/38, 63.2%) were hospitalized for ≤ 10 d.

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 38) |

| Preoperative ECOG score, n (%) | |

| 0-1 | 33 (86.8) |

| 2 | 5 (13.2) |

| Location of recurrent lesions, n (%) | |

| Pelvic cavity | 7 (18.4) |

| Abdominopelvic cavity | 16 (42.1) |

| Pelvic/abdominal cavity + retroperitoneal | 15 (39.5) |

| Residual lesions of the secondary surgery, n (%) | |

| R0 | 25 (65.8) |

| R1-R2 | 13 (34.2) |

| Intraoperative organ resection, n (%) | |

| No | 13 (34.2) |

| Yes | 25 (65.8) |

| Bleeding amount (mL), n (%) | |

| ≤ 400 | 20 (52.6) |

| 401-800 | 12 (31.6) |

| > 801 | 6 (15.8) |

| Perioperative complications, n (%) | |

| No | 29 (76.3) |

| Yes | 9 (23.7) |

| Postoperative chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| No | 2 (5.3) |

| Yes | 36 (94.7) |

| Postoperative use of targeted drugs, n (%) | |

| No | 33 (86.8) |

| Yes | 5 (13.2) |

| Postoperative hospital stay, n (%) | |

| ≤ 10 d | 24 (63.2) |

| 11-20 d | 12 (31.6) |

| > 20 d | 2 (5.2) |

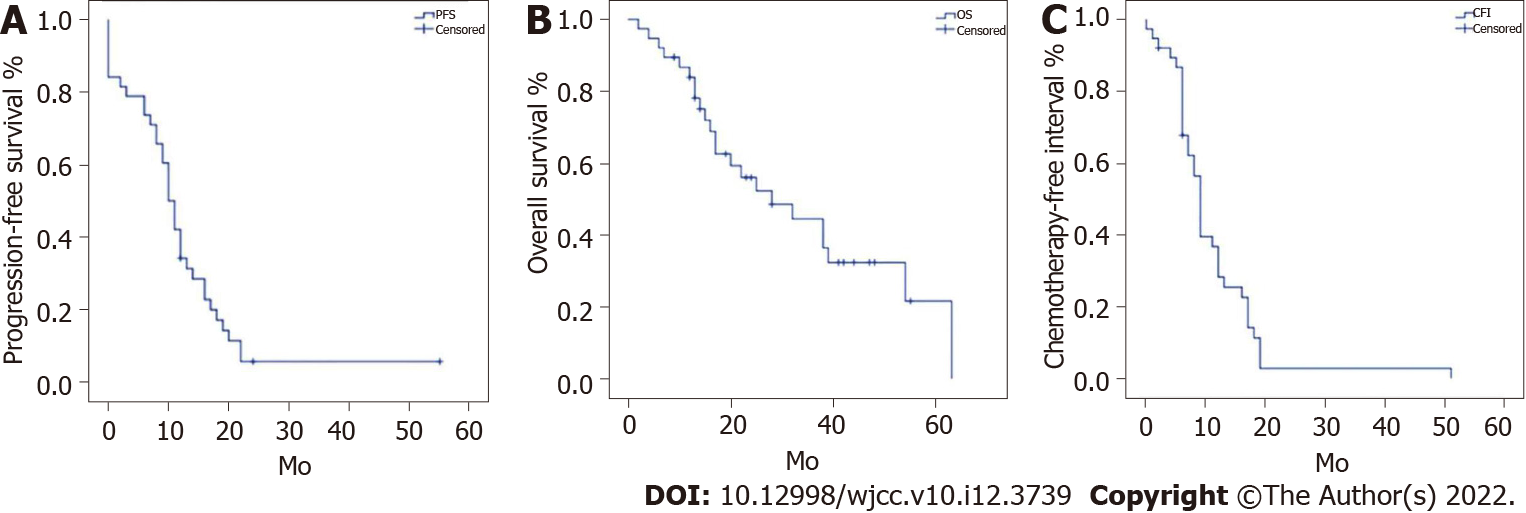

Figure 1 displays PFS, OS, and CFI in the 38 patients. Median PFS and OS were 10 (95%CI: 8.27-11.73) months and 28 (95%CI: 12.75-43.25) months, respectively; median CFI was 9 (95%CI: 8.06-9.94) months.

The results of Cox univariable analysis are shown in Table 3. Macroscopic residual lesions (HR = 3.29; 95%CI: 1.511-7.162; P = 0.003), intraoperative bleeding > 800 mL (HR = 2.862; 95%CI: 1.048-7.813; P = 0.04), and no postoperative chemotherapy (HR = 5.027; 95%CI: 1.061-23.828; P = 0.042) were associated with PFS. Pathological mixed type (HR = 11.285; 95%CI: 1.157-110.099; P = 0.037), macroscopic residual lesions (HR = 2.65; 95%CI: 1.115-6.298; P = 0.027), and no postoperative chemotherapy (HR = 57.66; 95%CI: 5.099-651.995; P = 0.001) were associated with OS. Pathological type of endometrioid carcinoma (HR = 0.32; 95%CI: 0.107-0.956; P = 0.041) and macroscopic residual lesions (HR = 2.777; 95%CI: 1.108-4.679; P = 0.025) were associated with CFI.

| Characteristics | PFS | OS | CFI | ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | |||||||||

| < 50 yrs | 0.929 | (0.469, 1.839) | 0.832 | 0.684 | (0.276, 1.694) | 0.412 | 1.06 | (0.538, 2.092) | 0.866 |

| ≥ 50 yrs | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Pathological type | |||||||||

| High-grade serous carcinoma | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Endometrioid carcinoma | 0.523 | (0.178, 1.543) | 0.241 | 0.697 | (0.199, 2.439) | 0.572 | 0.32 | (0.107, 0.956) | 0.041 |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 1.107 | (0.417, 2.942) | 0.838 | 0.788 | (0.224, 2.769) | 0.71 | 0.991 | (0.368, 2.67) | 0.985 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 0.491 | (0.065, 3.706) | 0.491 | 1.957 | (0.249, 15.399) | 0.524 | 0.238 | (0.031, 1.849) | 0.17 |

| Mixed type | 6.929 | (0.803, 59.809) | 0.078 | 11.285 | (1.157, 110.099) | 0.037 | 2.559 | (0.327, 20.016) | 0.371 |

| Pathological classification | |||||||||

| Highly differentiated | 0.822 | (0.249, 2.713) | 0.748 | 1.427 | (0.413, 4.931) | 0.574 | 0.644 | (0.193, 2.154) | 0.475 |

| Moderately differentiated | 0.583 | (0.137, 2.474) | 0.464 | 0.878 | (0.198, 3.881) | 0.863 | 0.348 | (0.082, 1.477) | 0.152 |

| Poorly differentiated | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Number of previous surgery | |||||||||

| 0 | 3.676 | (0.464, 29.112) | 0.218 | 6.505 | (0.755, 56.05) | 0.088 | 8.71 | (0.969, 78.245) | 0.053 |

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 2 | 0.807 | (0.276, 2.358) | 0.696 | 0.961 | (0.223, 4.151) | 0.958 | 1.02 | (0.351, 2.964) | 0.97 |

| 3 | 0.922 | (0.124, 6.864) | 0.937 | / | / | / | 1.251 | (0.167, 9.374) | 0.827 |

| Number of previous chemotherapy lines | |||||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 2 | 0.639 | (0.272, 1.504) | 0.305 | 0.573 | (0.165, 1.987) | 0.381 | 0.974 | (0.426, 2.229) | 0.951 |

| ≥ 3 | 0.81 | (0.307, 2.142) | 0.672 | 1.863 | (0.592, 5.865) | 0.288 | 1.182 | (0.476, 2.935) | 0.719 |

| FIGO staging of the first surgery | |||||||||

| I | 1.507 | (0.345, 6.58) | 0.586 | 1.634 | (0.358, 7.466) | 0.526 | 2.678 | (0.577, 12.437) | 0.209 |

| II | 0.752 | (0.352, 1.606) | 0.462 | 1.244 | (0.512, 3.027) | 0.63 | 0.672 | (0.319, 1.415) | 0.295 |

| III | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| IV | 0.419 | (0.097, 1.819) | 0.246 | / | / | / | 0.525 | (0.12, 2.285) | 0.39 |

| Residual lesions of the first surgery | |||||||||

| R0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| R1 | 1.122 | (0.505, 2.49) | 0.778 | 0.936 | (0.355, 2.469) | 0.894 | 1.059 | (0.484, 2.32) | 0.885 |

| R2 | 1.071 | (0.461, 2.489) | 0.874 | 0.422 | (0.119, 1.492) | 0.181 | 1.055 | (0.454, 2.456) | 0.9 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.629 | (0.278,1.423) | 0.266 | 1.081 | (0.394, 2.965) | 0.879 | 0.717 | (0.329, 1.56) | 0.401 |

| Remission time of chemotherapy before this secondary surgery | |||||||||

| ≤ 3 mo | 1.338 | (0.68, 2.631) | 0.399 | 0.767 | (0.322, 1.827) | 0.549 | 1.022 | (0.519, 2.014) | 0.95 |

| 3-6 mo | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Type of platinum resistance | |||||||||

| Secondary | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Primary | 0.982 | (0.471, 2.048) | 0.962 | 0.843 | (0.281, 2.529) | 0.761 | 1.354 | (0.647, 2.833) | 0.421 |

| Preoperative ECOG score | |||||||||

| 0-1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 2 | 0.643 | (0.226, 1.830) | 0.408 | 0.654 | (0.184, 2.323) | 0.511 | 0.575 | (0.221, 1.497) | 0.257 |

| Location of recurrent lesions | |||||||||

| Pelvic cavity | 0.799 | (0.305, 2.091) | 0.648 | 0.981 | (0.314, 3.062) | 0.973 | 0.661 | (0.239, 1.827) | 0.425 |

| Abdominopelvic cavity | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Pelvic/abdominal cavity + retroperitoneal | 0.818 | (0.391, 1.711) | 0.594 | 0.728 | (0.279, 1.9) | 0.516 | 0.867 | (0.422, 1.78) | 0.697 |

| Residual lesions of this secondary surgery | |||||||||

| R0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| R1-R2 | 3.29 | (1.511, 7.162) | 0.003 | 2.65 | (1.115, 6.298) | 0.027 | 2.777 | (1.108, 4.679) | 0.025 |

| Intraoperative organ resection | 1.251 | (0.616, 2.542) | 0.536 | 1.19 | (0.485, 2.921) | 0.705 | 1.586 | (0.772, 3.257) | 0.21 |

| Bleeding amount | |||||||||

| ≤ 400 mL | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 401-800 mL | 0.668 | (0.309, 1.444) | 0.305 | 0.634 | (0.222, 1.807) | 0.393 | 0.963 | (0.459, 2.021) | 0.92 |

| > 800 mL | 2.862 | (1.048, 7.813) | 0.04 | 2.422 | (0.83, 7.072) | 0.106 | 1.601 | (0.623, 4.111) | 0.328 |

| Perioperative complications | 0.669 | (0.289, 1.548) | 0.348 | 1.355 | (0.527, 3.478) | 0.528 | 0.713 | (0.307, 1.656) | 0.432 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 5.027 | (1.061, 23.828) | 0.042 | 57.66 | (5.099, 651.995) | 0.001 | / | / | / |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | / | / | / | ||||

| Postoperative use of targeted drugs | 0.518 | (0.178, 1.504) | 0.226 | 0.436 | (0.101, 1.887) | 0.267 | 0.745 | (0.277, 2.003) | 0.56 |

| Postoperative hospital stay | |||||||||

| ≤ 10 d | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 11-20 d | 1.212 | (0.573, 2.567) | 0.615 | 2.411 | (0.963, 6.037) | 0.06 | 1.104 | (0.524, 2.328) | 0.795 |

| > 20 d | 1.911 | (0.44, 8.308) | 0.388 | 3.98 | (0.853, 18.563) | 0.079 | 3.246 | (0.695, 15.154) | 0.134 |

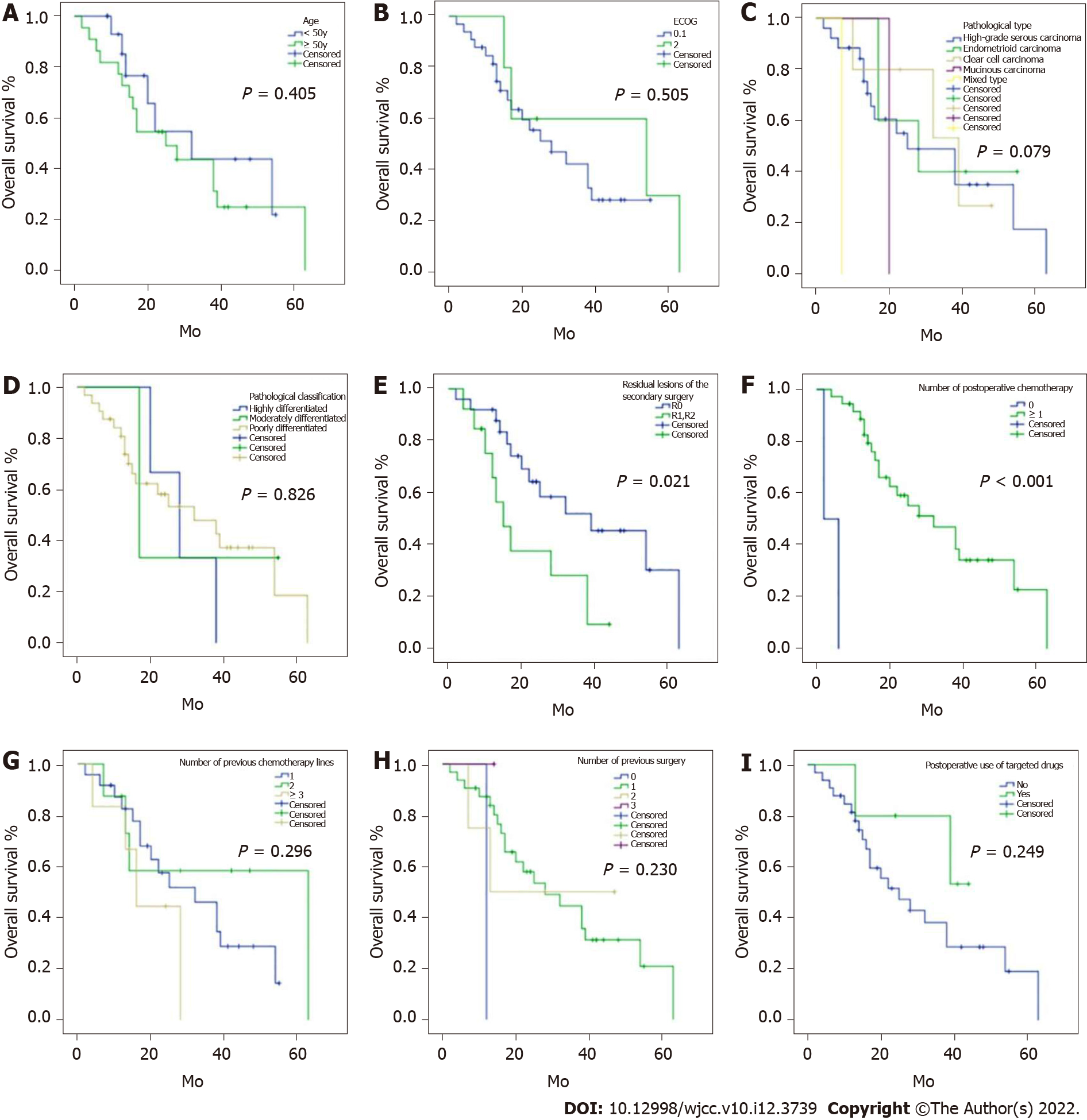

Subgroup analyses of important clinical indicators were performed based on the above univariate analysis (Figures 2-4). PFS in patients with R0 resection was significantly longer than that of the R1/2 resection group [12 (8.83, 15.17) vs 8 (2.27, 13.73) months; P = 0.001]. PFS was significantly longer in patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy than in those without postsurgical chemotherapy [11 (9.33, 12.67) vs 2 mo; P = 0.018] (Figure 2). OS was significantly prolonged in patients with R0 resection compared with those with R1/2 resection [39 (15.36, 62.64) vs 15 (8.71, 21.29) months; P = 0.021]. OS was significantly longer in patients administered postoperative chemotherapy than those without postoperative chemotherapy [32 (17.68, 46.32) vs 2 mo; P < 0.001] (Figure 3). CFI in patients with R0 resection was significantly prolonged than that of the R1/2 resection group [9 (6.22, 11.78) vs 6 (2.48, 9.52) months; P = 0.013]. Taken together, these results indicated that R0 resection and postoperative chemotherapy could significantly prolong PFS and OS, while R0 resection also significantly increased the CFI.

Grade ≥ 3 complications were observed, including rectovaginal fistula (n = 1), intestinal and urinary fistulas (n = 1), and renal failure-associated death (n = 1). Except for the patient who died after surgery, all other patients with complications were successfully managed. Two patients developed intestinal obstruction and showed improvement after conservative treatment. One patient with an intestinal fistula was relieved after ileostomy. One patient with an intestinal fistula complicated with a ureteral fistula showed improvement after ileal fistulation and ureteral stent placement under cystoscopy. One patient developed abdominal hemorrhage and was relieved after another surgery. Two patients with effusion of the spleen fossa and pelvic abscess were relieved by ultrasound-guided puncture drainage of the effusion and anti-inflammatory treatment. One patient developed renal dysfunction and electrolyte imbalance and showed improvement after medical treatment.

There are few treatment options for platinum-resistant recurrent EOC[10], and the available treatments have unsatisfactory efficacy, resulting in a poor prognosis. Cytoreductive surgery for advanced gynecologic tumors could be a good option[17,19-24], but controversies remain about its clinical value[16,17]. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of secondary cytoreductive surgery for treating platinum-resistant recurrent EOC. The results suggested that R0 resection and postoperative chemotherapy could significantly prolong PFS and OS, while R0 resection also significantly prolonged the CFI. Therefore, secondary cytoreductive surgery is feasible for treating platinum-resistant recurrent EOC. This study provides references for the selection of clinical therapeutic regimens.

As shown above, median PFS post-cytoreductive surgery was 10 mo, and median OS was 28 mo; a median CFI of 9 mo was recorded. Different studies have reported variable outcomes after surgery for recurrent EOC. Nevertheless, complicating the analysis of available results, many reports were not specifically focused on platinum-resistant EOC, and the obtained OS values were significantly longer than those described in the present study. Therefore, caution must be taken when comparing the shorter survival observed in this study with the literature. The current treatment option for platinum-resistant EOC is usually chemotherapy. Because there was no control group in the current study, no data were available for a chemotherapy group. Available data indicate that the effect of chemotherapy on platinum-resistant EOC is poor. Considering that the OS of patients with platinum-resistant EOC is about 1 year[10,15], an OS of 28 mo found in the present study could be seen as promising, despite the lack of a control group. This 28-mo median OS is shorter than that observed for EOC in general (without distinction on platinum resistance), 32-67 mo[17,19,21,23,24,29]. Additional multicenter studies could be carried out to examine those factors.

Another parameter that could influence survival is chemotherapy compliance, which can be indicated by the number of chemotherapy cycles. Generally, 6 cycles of chemotherapy are needed after recurrence[10]. However, given that patients with recurrent ovarian cancer usually undergo multiple lines of chemotherapy, chemotherapy tolerance can be reduced, and 4-6 cycles could be considered to indicate good compliance. In addition, treatment costs can limit the number of chemotherapy cycles.

In platinum-sensitive EOC, Canaz et al[30] reported that ascites and R0 resection are associated with longer PFS. In addition, Schorge et al[21] demonstrated that residual lesion < 5 mm, and < 5 sites of disease relapse are associated with improved OS. Furthermore, Salani et al[19] showed that disease-to-recurrence interval < 18 mo, 1-2 recurrent sites, and R0 resection are associated with improved survival. Moreover, Eisenkop et al[23] showed that a long disease-free interval after the primary treatment, R0 resection, salvage chemotherapy, and recurrent lesions < 10 cm are associated with improved survival. Besides, Onda et al[24] showed that R0 resection, disease-free interval > 12 mo, no liver metastasis, solitary lesion, and lesion < 6 cm are associated with improved survival. Shih et al[22] highlighted that maximum cytoreductive efforts should be made in patients with recurrent EOC. On the other hand, in platinum-resistant EOC, ascites and tumor size kinetics during chemotherapy appear to be the two most influential factors associated with OS[10]. Optimal tumor debulking improves patient prognosis in patients with platinum resistance after neoadjuvant chemotherapy[31]. In the present study, R0 resection and postoperative chemotherapy were associated with longer PFS and OS, while R0 resection also significantly prolonged the CFI. Taken together, these results indicate that R0 resection is a critical factor for the success of salvage cytoreduction therapy in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent EOC. The above results suggested that in case of satisfactory effects achieved by cytoreductive surgery for platinum-resistant EOC, the patients would benefit from the surgery regardless of previous FIGO stage, pathological type, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the number of chemotherapy lines, and the type of drug resistance. Furthermore, studies reported that the management of malignant ascites and malignant bowel obstruction could by itself improve survival in patients with treatment-resistant disease[32-36]. Such supportive and palliative treatments could also play a role in survival.

Surgical complications in platinum-resistant recurrent EOC cases undergoing secondary cytoreductive surgery also influence the postoperative quality of life and survival. Therefore, the safety of the surgical treatment, the resectability of the recurrent lesions, and the incidence of perioperative complications are important indicators of treatment safety and feasibility. In the present study, the complication rate was 24%, which corroborates previous studies[17,19-24].

The present study examined CFI, but this outcome has some limitations. Indeed, some patients with poor chemotherapy tolerance or insensitivity to chemotherapy could show long CFI but a short OS. On the other hand, a short CFI could be associated with a long OS because of previous treatments. Nevertheless, the CFI may reflect the patient’s quality of life[37]. In some patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, post-chemotherapy CFI was prolonged by secondary cytoreductive surgery. In addition, for some patients with elevated CA125 amounts but no evidence of disease in clinical and imaging examinations, the CFI could be prolonged, thereby keeping possibly effective options once symptoms occur.

This study was a retrospective case series, and the absence of a control group was the main limitation. There were few patients with platinum-resistant recurrent EOC in our center, and many had incomplete chemotherapy data because they returned to their local hospitals after the first chemotherapy cycles. This study did not have a control group. Therefore, additional large prospective, multicenter, randomized clinical trials are needed to provide further high-level evidence.

In patients with platinum-resistant recurrent EOC, secondary cytoreductive surgery could significantly improve PFS, OS, and CFI in case of no macroscopic residual lesions. Postoperative chemotherapy could further improve PFS and OS. Therefore, secondary cytoreductive surgery has certain clinical feasibility, providing a potential treatment option for these patients.

Ovarian cancer is one of the three most common malignant tumors of the female reproductive tract and ranks first in terms of mortality among gynecological tumors. Epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) is the most common ovarian malignancy, accounting for 90% of all primary ovarian tumors.

The clinical value of cytoreductive surgery in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent EOC remains largely unclear.

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of secondary cytoreductive surgery to treat platinum-resistant recurrent EOC.

It was a retrospective study of the clinical data of patients with platinum-resistant EOC admitted to the Cancer Hospital of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences between September 2012 and June 2018.

R0 resection and postoperative chemotherapy significantly prolonged progression-free survival and overall survival (all P < 0.05), and R0 resection also significantly prolonged chemotherapy-free interval (P < 0.05).

Secondary cytoreductive surgery is feasible for the treatment of platinum-resistant recurrent EOC.

The findings provide important references for the selection of clinical therapeutic regimens.

The authors acknowledge help from Prof. Ping Zhang and Prof. Fei-Jiang Yu.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gupta S, United States; Paholpak P, Thailand S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Mallen AR, Townsend MK, Tworoger SS. Risk Factors for Ovarian Carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32:891-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55747] [Article Influence: 7963.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 3. | Jiang X, Tang H, Chen T. Epidemiology of gynecologic cancers in China. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29:e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N, Sessa C; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi24-vi32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baldwin LA, Huang B, Miller RW, Tucker T, Goodrich ST, Podzielinski I, DeSimone CP, Ueland FR, van Nagell JR, Seamon LG. Ten-year relative survival for epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:612-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Birch JM, Pang D, Alston RD, Rowan S, Geraci M, Moran A, Eden TO. Survival from cancer in teenagers and young adults in England, 1979-2003. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:830-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chan JK, Cheung MK, Husain A, Teng NN, West D, Whittemore AS, Berek JS, Osann K. Patterns and progress in ovarian cancer over 14 years. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:521-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, Zhang S, Zou X, Wang N, Zhang L, Tang J, Chen J, Wei K, Huang S, Wang J, Yu L, Zhao D, Song G, Shen Y, Yang X, Gu X, Jin F, Li Q, Li Y, Ge H, Zhu F, Dong J, Guo G, Wu M, Du L, Sun X, He Y, Coleman MP, Baade P, Chen W, Yu XQ. Cancer survival in China, 2003-2005: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1921-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 49.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lawrie TA, Winter-Roach BA, Heus P, Kitchener HC. Adjuvant (post-surgery) chemotherapy for early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD004706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sostelly A, Mercier F. Tumor Size and Overall Survival in Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Treated With Chemotherapy and Bevacizumab. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2019;13:1179554919852071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mittica G, Ghisoni E, Giannone G, Genta S, Aglietta M, Sapino A, Valabrega G. PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2018;13:392-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Franzese E, Centonze S, Diana A, Carlino F, Guerrera LP, Di Napoli M, De Vita F, Pignata S, Ciardiello F, Orditura M. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;73:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pignata S, Lorusso D, Scambia G, Sambataro D, Tamberi S, Cinieri S, Mosconi AM, Orditura M, Brandes AA, Arcangeli V, Panici PB, Pisano C, Cecere SC, Di Napoli M, Raspagliesi F, Maltese G, Salutari V, Ricci C, Daniele G, Piccirillo MC, Di Maio M, Gallo C, Perrone F; MITO 11 investigators. Pazopanib plus weekly paclitaxel versus weekly paclitaxel alone for platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory advanced ovarian cancer (MITO 11): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:561-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Elit L, Hirte H. Palliative systemic therapy for women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: current options. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:107-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ethier JL, Wang L, Oza AM, Lheureux S. Survival outcomes in patients with platinum-resistant (PL-R) ovarian cancer (OC): The Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM) experience. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:e17049. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lorusso D, Mancini M, Di Rocco R, Fontanelli R, Raspagliesi F. The role of secondary surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:613980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schorge JO, Garrett LA, Goodman A. Cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian cancer: quo vadis? Oncology (Williston Park). 2011;25:928-934. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Gockley A, Melamed A, Cronin A, Bookman MA, Burger RA, Cristae MC, Griggs JJ, Mantia-Smaldone G, Matulonis UA, Meyer LA, Niland J, O'Malley DM, Wright AA. Outcomes of secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:625.e1-625.e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Salani R, Santillan A, Zahurak ML, Giuntoli RL 2nd, Gardner GJ, Armstrong DK, Bristow RE. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for localized, recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: analysis of prognostic factors and survival outcome. Cancer. 2007;109:685-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harter P, Heitz F, Mahner S, Hilpert F, du Bois A. Surgical intervention in relapsed ovarian cancer is beneficial: pro. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 10:x33-x34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schorge JO, Wingo SN, Bhore R, Heffernan TP, Lea JS. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;108:123-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shih KK, Chi DS. Maximal cytoreductive effort in epithelial ovarian cancer surgery. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010;21:75-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Eisenkop SM, Friedman RL, Spirtos NM. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in the treatment of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:144-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Onda T, Yoshikawa H, Yasugi T, Yamada M, Matsumoto K, Taketani Y. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: proposal for patients selection. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1026-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bristow RE, Puri I, Chi DS. Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in RCA: 21563] [Article Influence: 1347.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Petrillo M, Pedone Anchora L, Tortorella L, Fanfani F, Gallotta V, Pacciani M, Scambia G, Fagotti A. Secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with isolated platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: a retrospective analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:257-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Strong VE, Selby LV, Sovel M, Disa JJ, Hoskins W, Dematteo R, Scardino P, Jaques DP. Development and assessment of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center's Surgical Secondary Events grading system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1061-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Musella A, Marchetti C, Palaia I, Perniola G, Giorgini M, Lecce F, Vertechy L, Iadarola R, De Felice F, Monti M, Muzii L, Angioli R, Panici PB. Secondary Cytoreduction in Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: A Single-Institution Experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4211-4216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Canaz E, Grabowski JP, Richter R, Braicu EI, Chekerov R, Sehouli J. Survival and prognostic factors in patients with recurrent low-grade epithelial ovarian cancer: An analysis of five prospective phase II/III trials of NOGGO metadata base. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Le T, Faught W, Hopkins L, Fung-Kee-Fung M. Can surgical debulking reverse platinum resistance in patients with metastatic epithelial ovarian cancer? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31:42-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Courtney A, Nemcek AA Jr, Rosenberg S, Tutton S, Darcy M, Gordon G. Prospective evaluation of the PleurX catheter when used to treat recurrent ascites associated with malignancy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1723-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Brooks RA, Herzog TJ. Long-term semi-permanent catheter use for the palliation of malignant ascites. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:360-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Iyengar TD, Herzog TJ. Management of symptomatic ascites in recurrent ovarian cancer patients using an intra-abdominal semi-permanent catheter. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2002;19:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Roeland E, von Gunten CF. Current concepts in malignant bowel obstruction management. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009;11:298-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Baron TH. Interventional palliative strategies for malignant bowel obstruction. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009;11:293-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, Paulk ME, LeBlanc TW, Schneider BJ, Garrido MM, Reid MC, Berlin DA, Adelson KB, Neugut AI, Maciejewski PK. Chemotherapy Use, Performance Status, and Quality of Life at the End of Life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:778-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |