Published online Apr 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3306

Peer-review started: November 24, 2021

First decision: December 26, 2021

Revised: December 29, 2021

Accepted: February 15, 2022

Article in press: February 15, 2022

Published online: April 6, 2022

Processing time: 125 Days and 8.3 Hours

Hemobilia occurs when there is a fistula between hepatic blood vessels and biliary radicles, and represents only a minority of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages. Causes of hemobilia are varied, but liver abscess rarely causes hemobilia and only a few cases have been reported. Here, we present a case of atypical hemobilia caused by liver abscess that was successfully managed by endoscopic hepatobiliary intervention through endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

A 54-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a history of right upper quadrant abdominal colic and repeated fever for 6 d. Abdominal sonography and enhanced computed tomography revealed that there was an abscess in the right anterior lobe of the liver. During hospitalization, the patient developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a duodenal ulcer bleeding that was treated with three metal clamps. However, the hemodynamics was still unstable. Hence, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed again and fresh blood was seen flowing from the ampulla of Vater. Selective angiography did not show any abnormality. An endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube was inserted into the right anterior bile duct through ERCP, and subsequently cold saline containing (-)-nora

Hemobilia should be considered in the development of liver abscess, and endoscopy is essential for diagnosis and management of some cases.

Core Tip: Hemobilia occurs when there is a communication between intrahepatic blood vessels and biliary radicles caused by injury or some diseases, and represents only a minority of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages. Liver abscess rarely causes hemobilia and only a few cases have been reported. Here, we present a rare case of atypical hemobilia caused by liver abscess that was successfully managed by catheter‐directed infusion of diluted (-)-noradrenaline with an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube.

- Citation: Zou H, Wen Y, Pang Y, Zhang H, Zhang L, Tang LJ, Wu H. Endoscopic-catheter-directed infusion of diluted (-)-noradrenaline for atypical hemobilia caused by liver abscess: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(10): 3306-3312

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i10/3306.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3306

Hemobilia is defined as hemorrhage in the biliary system due to an abnormal communication between intrahepatic blood vessels and bile ducts. It represents only a minority of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages[1]. Right upper quadrant colicky abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, hematemesis and melena are the classic clinical presentations of hemobilia, described as Quincke’s triad. There are many possible causes of hemobilia. Recently iatrogenic injury has accounted for more than half of hemobilia cases, other cases have traumatogenic, neoplastic, inflammatory, vascular causes and some are caused by gallstones[2]. Liver abscess can also cause hemobilia, although the frequency is low[3]. Here, we present a rare case of hemobilia caused by liver abscess that was successfully managed by catheter-directed infusion of diluted (-)-noradrenaline with an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube. So far, there are no reports about this treatment for intrahepatic hemobilia caused by liver abscess. Therefore, we believe that this particular case can provide an alternative option for the management of hemobilia.

A 54-year-old man was admitted with right upper quadrant abdominal colic and repeated fever.

The patient developed right upper abdominal pain and repeated fever 7 d ago, and the symptoms were not relieved after treatment in the local hospital. Therefore, he was transferred to our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment.

The patient had a medical history of peptic ulcer and there was no past history of cholangitis or obstructive jaundice.

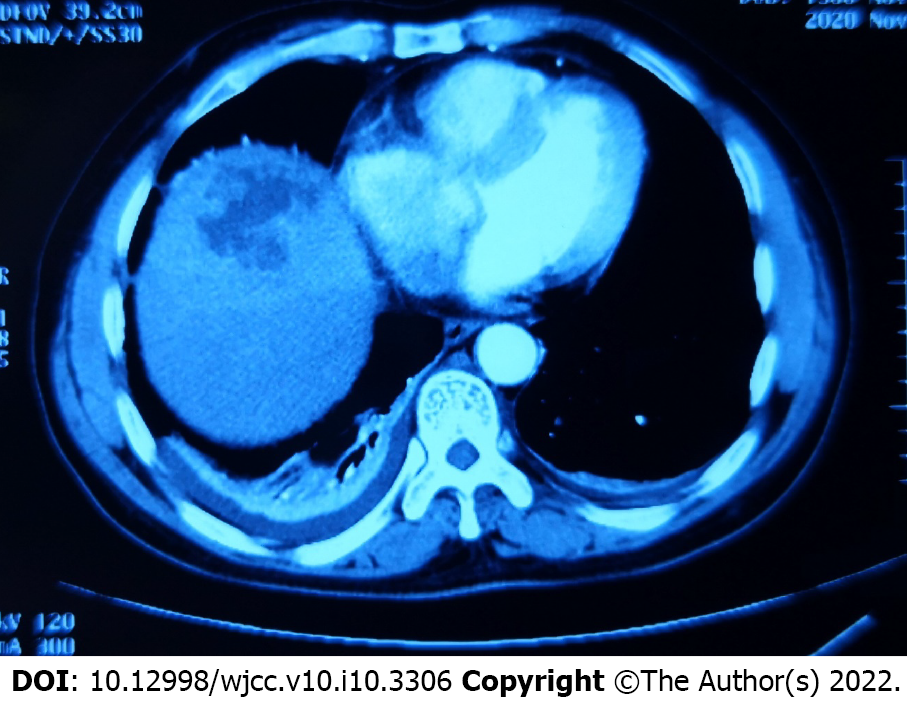

Enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a patchy slightly low-density image (an abscess) at the top of the liver and gallstone (Figure 1). Abdominal sonography revealed that there was an abscess in the right anterior lobe of the liver.

Initial laboratory investigation presented hemoglobin 107 g/L, white blood cell count 13.11 × 109/L, platelet count 206 × 109/L, serum albumin 34.2 g/L, alanine aminotransferase 43 IU/L, glutamic oxalacetic transaminase 31 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 232.6 IU/L, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 231.3 IU/L, total bilirubin 18.3 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 9.7 μmol/L, and hypersensitive C-reactive protein 73.77 mg/L. Coagulation profiles were within normal limits, but fecal occult blood was weakly positive. In addition, detection of ameba, enteric typhoid and rotavirus was also negative.

On admission, he had normal temperature with blood pressure of 124/86 mmHg and pulse rate of 86 beats/min. Physical examination revealed that there was moderate tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen with no rebound tenderness or Murphy’s sign, and no jaundice of skin and sclera.

The patient had no family history that was related to the present illness.

Diagnosis of liver abscess and the possibility of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

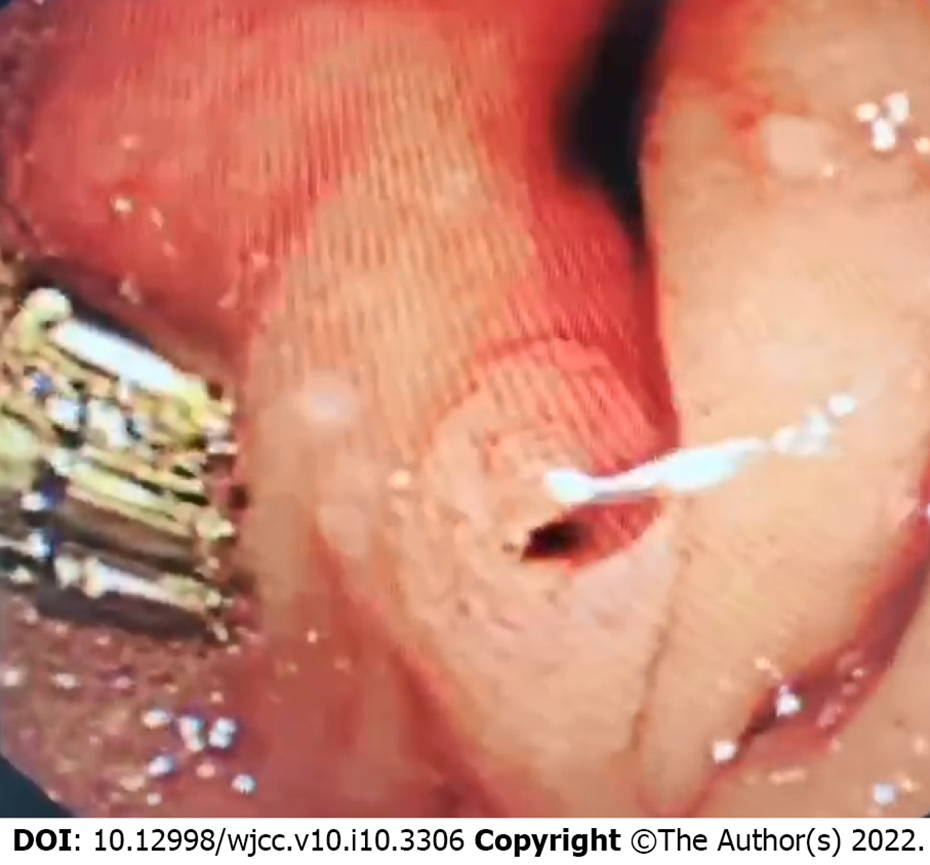

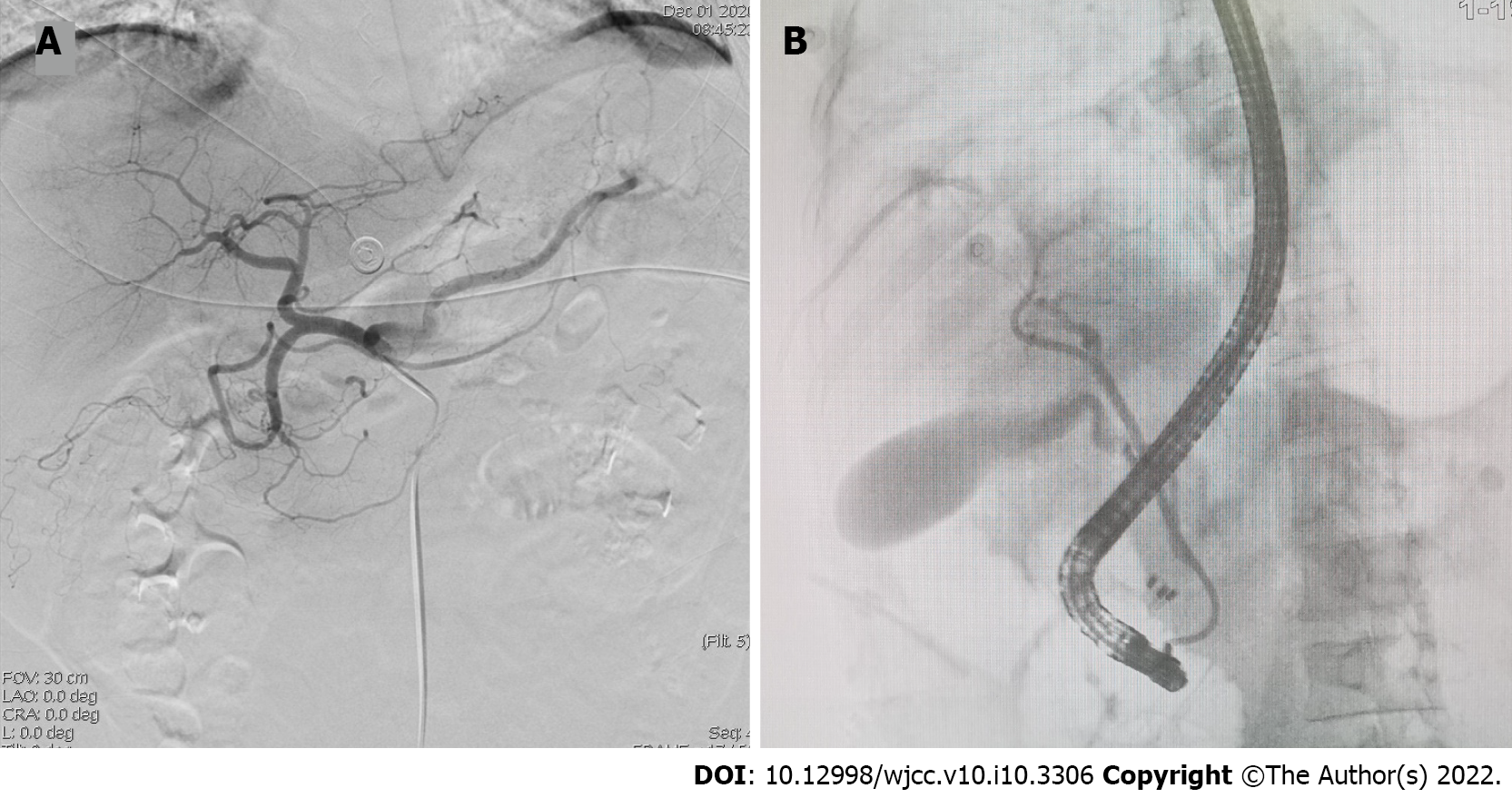

The patient received ultrasound-guided percutaneous (catheter) drainage of the abscess cavity and was given cephalosporin antibiotics and hemostatic drugs when he completed the examination. On day 2 of hospitalization, the patient had three episodes of melena and one of syncope for a few seconds. His hemoglobin decreased to 60 g/L with unstable hemodynamics demonstrated by increased pulse rate of 103 beats/min and declined blood pressure of 90/63 mmHg. Immediate resuscitation was carried out with infusion of 6 U packed red cells and 400 mL fresh frozen plasma. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed duodenal ulcer bleeding, and three metal clamps were applied to stop the bleeding. After a brief period of hemodynamic stabilization, hemoglobin levels dropped to 63 g/L. Therefore, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed once again and fresh blood was seen flowing from the ampulla of Vater (Figure 2). However, selective angiography did not show any abnormality (Figure 3A). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) indicated no filling defects in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, but when the guide-wire entered the marginal bile duct of the right anterior branch, a large amount of bloody bile was seen spilling from the ampulla of Vater. An ENBD tube was inserted into the right anterior bile duct, and subsequently cold saline containing (-)-noradrenaline (0.9% saline 100 mL with 8 mg (-)-noradrenaline) was infused into the bile duct lumen through the ENBD tube (10 mL/h) (Figure 3B).

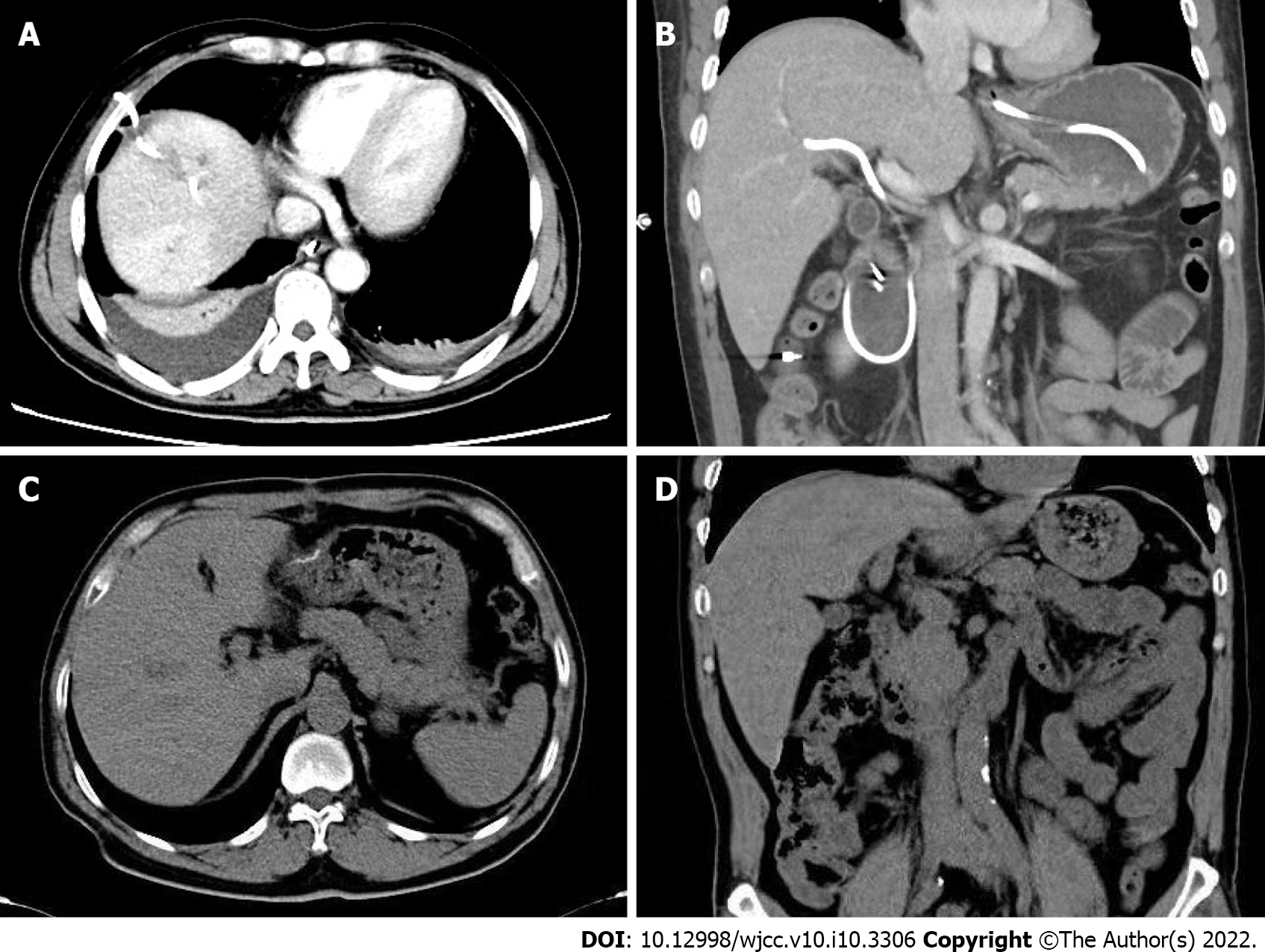

There was no episode of further bleeding, and abdominal CT scan performed on postoperative day 10 showed that the abscess had basically disappeared (Figure 4A and B). The patient was discharged without any complications. One month later, abdominal CT revealed no expansion of the intrahepatic bile duct and complete absorption of the liver abscess (Figure 4C and D).

Hemobilia represents only a minority of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages and occurs when there is a fistula between intrahepatic blood vessels and biliary radicles. The etiology of hemobilia is diverse. It can have traumatogenic causes; iatrogenic causes (percutaneous liver procedures, hepatobiliary surgery and endoscopic hepatobiliary procedures); or noniatrogenic causes (cholelithiasis, inflammatory diseases, calculous cholecystitis, cholangitis, and parasitic infection); and it may be due to vascular disorders (aneurysms); neoplasms and coagulopathy[4]. In recent years, because of the increasing popularity of interventional diagnosis and treatment of the hepatobiliary tract, most cases of hemobilia have been caused by iatrogenic injury[4]. Although liver abscess can also cause hemobilia, only a few cases have been reported[3-5]. At present, the specific pathological mechanism of hemobilia caused by liver abscess is still unclear, and the possible explanation is erosion or segmental ischemia of the distal bile duct wall by abscess[5].

The classic clinical presentation of hemobilia is described as Quincke’s triad of right upper quadrant colicky abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, hematemesis and melena. However, only 22%-35% of cases present with the triad, and even some cases manifest clinical silence[1]. On admission, our patient presented signs of infection supported by the laboratory findings that were compatible with liver abscess. Only a weakly positive test for fecal occult blood suggested the possibility of gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient developed hemodynamic instability and melena on the second day of hospitalization. During the clinical course of hemobilia, he did not manifest obstructive jaundice because there were no intraductal blood clots to induce biliary stasis, and the formation of clots may be related to the location, amount and rate of bleeding.

Diagnosis of hemobilia is challenging because it is uncommon, especially in some cases where there are no risk factors such as recent biliary tract manipulation or trauma. Imaging techniques such as ultrasound and computed tomography can be helpful for the initial diagnosis and guiding the choice of treatment, although the findings are often indirect and nonspecific[6]. Upper endoscopy is the most frequent way to provide direct visible evidence of bleeding from the ampulla of Vater, particularly in suspected cases of hemobilia, and repeated upper endoscopy or side-viewing duodenoscopy should be considered[7]. Until recently, conventional angiography was not recommended as a first-line management because of its invasive nature, and angiographic embolization can only be used if the bleeding is vigorous or if vascular abnormalities (aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm) are visible[8,9]. Surgical intervention plays a complementary role in the treatment of hemobilia in cases of failed embolization[9]. In the present case, repeated abdominal ultrasound examination at admission did not reveal bile duct expansion inside or outside the liver, and there was only a strong echo vocal shadow in the gallbladder cavity. We initially misinterpreted upper gastrointestinal bleeding from ulcer bleeding due to peptic ulcer. A second endoscopy finally revealed fresh blood leak from the ampulla of Vater. However, selective angiography did not show any abnormality, and it was suspected that the bleeding originated from a portal vein or hepatic vein branch. ERCP was performed to manage hemostasis through a variety of endoscopic techniques and accessories, which depends on the cause, location and vascular source[10,11]. Because the abscess was located in the right lobe of the liver, and when a guide-wire entered the marginal bile duct of the right anterior branch, a large amount of bloody bile was seen spilling from the ampulla of Vater. In light of this situation, we speculated that the bleeding site was located in the right anterior bile duct, thus an ENBD tube was placed to implement catheter-directed infusion of diluted (-)-noradrenaline. This technique offers unique benefits and it is effective and safe especially for submucosal venous hemorrhage of the bile duct[12], but it is not carried out routinely mainly due to related discomfort, technically cumbersome procedures and easy inadvertent catheter withdrawal[13]. Hemobilia caused by liver abscess in our patient was obviously cured without further operative intervention.

The possibility of hemobilia should be considered in the development of liver abscess although the frequency of the complication is low. Endoscopic-catheter-directed infusion of hemostatics via ENBD tube is an effective and safe conservative treatment for hemobilia caused by liver abscess.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cerwenka H, Chow WK S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Green MH, Duell RM, Johnson CD, Jamieson NV. Haemobilia. Br J Surg. 2001;88: 773-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Murugesan SD, Sathyanesan J, Lakshmanan A, Ramaswami S, Perumal S, Perumal SU, Ramasamy R, Palaniappan R. Massive hemobilia: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. World J Surg. 2014;38:1755-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Joo YE, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS, Kim HJ, Kim SJ. Hemobilia caused by liver abscess due to intrahepatic duct stones. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:507-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cathcart S, Birk JW, Tadros M, Schuster M. Hemobilia: An Uncommon But Notable Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:796-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Al-Qahtani HH. Hemobilia due to liver abscess. A rare cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:604-606. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Feng W, Yue D, ZaiMing L, ZhaoYu L, XiangXuan Z, Wei L, QiYong G. Iatrogenic hemobilia: imaging features and management with transcatheter arterial embolization in 30 patients. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2016;22:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim KH, Kim TN. Etiology, clinical features, and endoscopic management of hemobilia: a retrospective analysis of 37 cases. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:296-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Srivastava DN, Sharma S, Pal S, Thulkar S, Seith A, Bandhu S, Pande GK, Sahni P. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of hemobilia. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:439-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhornitskiy A, Berry R, Han JY, Tabibian JH. Hemobilia: Historical overview, clinical update, and current practices. Liver Int. 2019;39:1378-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Fasoulas K, Katsinelos T, Pilpilidis I, Paroutoglou G. Endoscopic hemostasis using monopolar coagulation for postendoscopic sphincterotomy bleeding refractory to injection treatment. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:84-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Itoi T, Yasuda I, Doi S, Mukai T, Kurihara T, Sofuni A. Endoscopic hemostasis using covered metallic stent placement for uncontrolled post-endoscopic sphincterotomy bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:369-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wen XD, Wang T, Huang Z, Zhang HJ, Zhang BY, Tang LJ, Liu WH. Step-by-step strategy in the management of residual hepatolithiasis using post-operative cholangioscopy. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:853-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moparty RK, Brown RD, Layden TJ, Chirravuri V, Wiley T, Venu RP. Dissolution of blood clots in the biliary ducts with a thrombolytic agent infused through nasobiliary catheter. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:436-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |