Published online Apr 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3188

Peer-review started: July 17, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: October 29, 2021

Accepted: February 22, 2022

Article in press: February 22, 2022

Published online: April 6, 2022

Processing time: 254 Days and 17.7 Hours

Hem-o-Lok clip (HOLC) has been widely used in laparoscopic surgery due to its ease of application and secure clamping, though the rare complications associated with this technique should not be ignored. The rare complications of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy consist of the clip migrating into the renal pelvis and acting as a nidus for stone formation.

The case described here involved a 63-year-old woman who was found with stones in the right kidney and upper ureter during a recent reexamination following laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. We performed percutaneous nephrolithotomy for her, but during the operation, it was found that the center of the stone within the kidney was a HOLC, which was removed with forceps. For this reason, we speculate that the HOLC, which was employed to halt tumor wound bleeding, spontaneously drifted into the renal pelvis and formed kidney stones, with the clip being initially misdiagnosed as a kidney stone.

By reviewing related case reports, we conclude that in order to prevent complications related to HOLC, loose clips should be actively searched for and retrieved from the wound during urinary tract surgery, while the deployment of clips in close proximity of anastomotic stoma of collecting systems should be avoided.

Core Tip: The present case involved a patient who was found to have a spontaneously drifted Hem-o-Lok into the renal pelvis and formed stones after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. We conclude that in order to prevent complications related to Hem-o-Lok, loose clips should be actively sought and retrieved from the wound during urinary system surgery, while the deployment of clips in close proximity to the anastomotic stoma of collecting systems should be avoided.

- Citation: Sun J, Zhao LW, Wang XL, Huang JG, Fan Y. Migration of a Hem-o-Lok clip to the renal pelvis after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(10): 3188-3193

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i10/3188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3188

The nonabsorbable Hem-o-Lok polymer ligating clip (HOLC) was introduced in 1999 and brought a novel and efficient ligation method for surgery, gradually replacing titanium clips and endovascular stapling devices, and is favored by surgeons[1]. With its unique locking mechanism, this kind of polymer clip potentially reduces the risk of displacement from tissue. In addition, its narrow profile, good tactile feedback with closure, ability to remove the clip, and no artifact production on imaging techniques also render it increasingly widely employed, particularly within various laparoscopic surgical procedures. Within the urinary system, HOLC is commonly used for ligating the ureter, renal artery, and renal vein, and halting kidney or prostate excision bed bleeding, and thus plays an important role in the popularization of laparoscopy in urology. Through a urologist’s perspective, HOLC has unique advantages in avoiding thermal injury during dissection of the neurovascular bundle in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN), laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP) and even robot-assisted laparoscopic radical pro

However, a central issue remains regarding HOLC stability. Although such novel devices for tissue and blood vessel occlusions are widely accepted, few data are available to support their efficacy and safety. Bleeding incidents caused by HOLC-induced damage during operation or emergency shedding post operation have been reported[2]. However, it is rare to report that foreign bodies are formed due to the long-term displacement of clips postoperatively, which leads to related complications. This report presents a case of spontaneous migration of a surgical clip into the collecting system after LPN, which led to the occurrence of renal stones and misdiagnosis prior to surgery.

A 63-year-old woman was admitted to our service due to urinary ultrasound revealing right renal and ureteral calculi.

In the past four years, the patient did not have any urinary tract symptoms. Until 48 h prior to admission, she was examined by urinary ultrasound for follow-up of the renal cell carcinoma, which revealed a right kidney stone and upper ureteral stone. She had no fever, no lower back pain, no urinary tract irritation, no gross hematuria, or any other uncomfortable symptoms.

Four years ago, LPN for a minute right renal mass was performed in our hospital. During surgery, a mass of 2.5 cm × 2.3 cm in the lower pole of the right kidney was identified. The renal tumor was completely removed along the edge of the renal tumor (0.5 cm margin), and the capsule was intact. Post resection, a fissure was found at the ureteropelvic junction. Therefore, a 3-0 Vicryl was applied to repair the fissure, and a 2-0 Vicryl was applied to the edge of the renal parenchyma. Furthermore, surgical bed hemostasis had been achieved with automatic non-absorbing surgical clips. The postoperative course was uneventful, and pathology confirmed this to be renal cell carcinoma of the right kidney (T1a/N0/M0). Consequently, the patient was discharged from hospital and instructed to have regular re-examinations.

There was no family history of urinary calculi or tumors.

Physical examination showed positive percussion pain of the right kidney and no other positive signs.

No obvious abnormalities were found in hematological indicators and routine urinalyses for this particular patient.

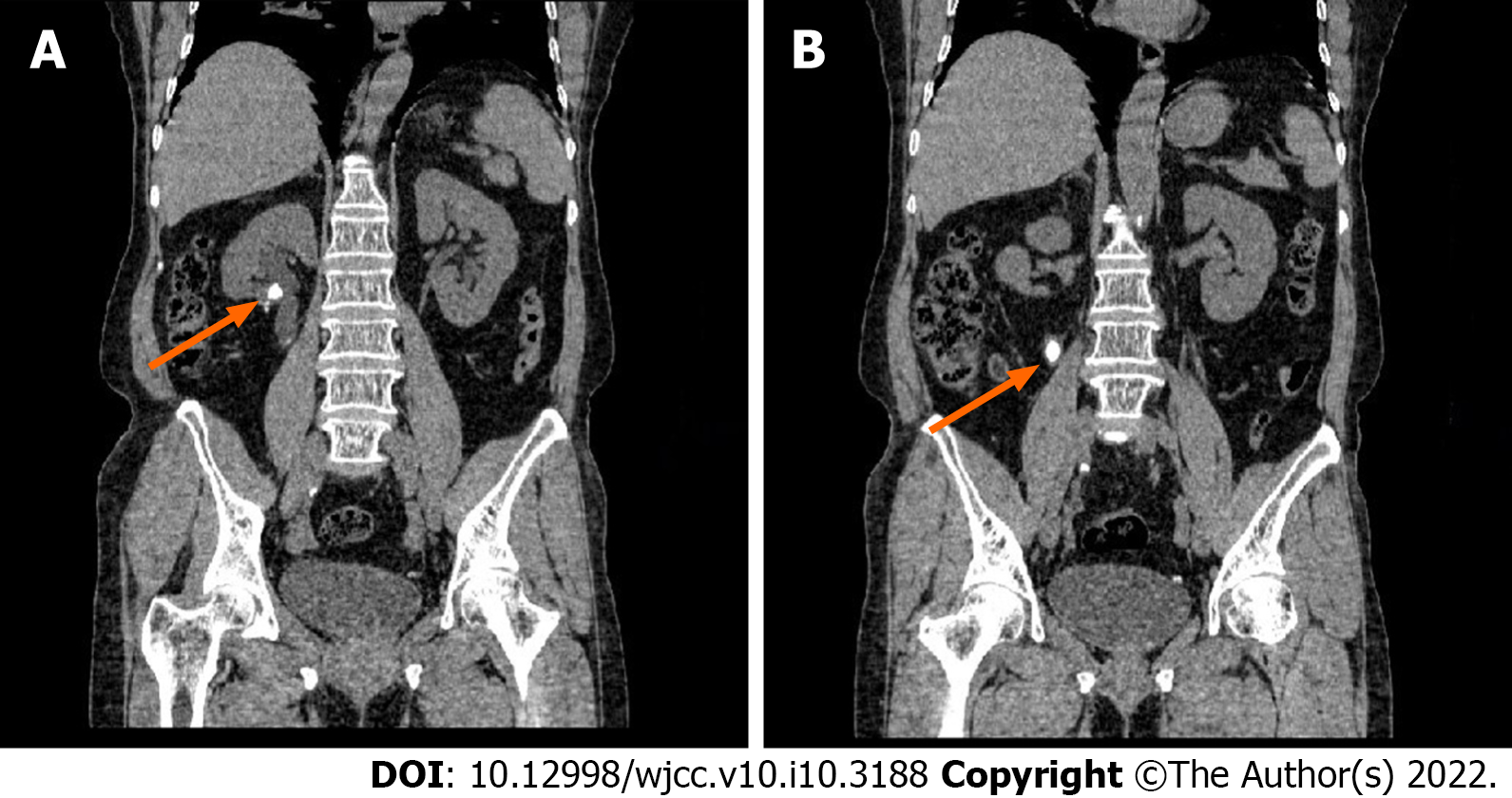

B-ultrasound demonstrated that the right kidney collecting system was separated and a plurality of liquid-segregated dark areas could be visualized, with a strong echo of 1.1 × 0.8 cm within, and the upper part of the right kidney ureter was dilated, with a strong echo of 2.1 cm × 1.1 cm within. Physical examination revealed right costovertebral angle tenderness, and the rest had no positive signs. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated that the lower pole of the right kidney was absent post-surgery, with a high-density fringe, and two opacities could be seen in the right renal pelvis (A:1295HU) and proximal ureter (B:1335HU), respectively (Figure 1). A preliminary diagnosis of right hydronephrosis with nephroureteral calculi was concluded.

The final revised diagnosis was a right renal foreign body with calculus formation and right hydronephrosis with ureteral calculus.

Based on the above findings, we decided to perform percutaneous nephrolithotomy for this patient. During surgery, there were stones in the lower and middle-right renal calices and the upper part of the right ureter, which were both approximately 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm in size. Following an initial renal pelvic stone fragmentation with the ultrasound device, it was found that the center of the stones was a white rectangular foreign body, surprisingly (Figure 2A). This was consequently removed with a forceps (Figure 2B). After careful in vitro examination, it was confirmed as a medium-sized surgical clip (Figure 2C).

Postoperatively, the patient had urinary tract infection, which improved following antibiotic treatment, and she was eventually discharged from hospital. Presently, the patient is followed regularly, with no obvious abnormality found in the collecting system of both kidneys.

Intrarenal foreign bodies are extremely rare-expected circumstances, and the gastrointestinal tract is one of the most common routes for reaching the kidney. Such foreign bodies are typically torn objects in food, such as fish bones, needles, pins, hairgrips, and toothpicks[2]. Such clinical manifestations also vary, including purulent cutaneous fistulae, renal and perirenal pseudotumors, and the formation of kidney stones[3-5]. These foreign bodies can also remain asymptomatic for years, as reported in this case. A proper follow-up with radiological evaluation is helpful to ensure a proper diagnosis prior to symptom manifestations. When evaluating patients who have had surgical experience, a high degree of suspicion index is essential. In this case, the diagnosis was not suspected preoperatively, since the foreign body had no radiopaque markers and was accompanied with stones, and it could not be described by typical X-ray manifestations or computed tomography alone.

Foreign bodies due to surgical instruments being left behind after kidney surgery are rarely reported in the literature, and spontaneous metastasis to the intrarenal site is even rarer. From January 1999 to July 2020, a total of 262 adverse events involving HOLC were reported to the Maude database. Due to consequent medical and legal issues, we believe that such adverse events are obviously underreported. Among them, in the general surgical literature, it has been reported that the clip shifted to the common bile duct after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and induced gallstone formation or cholangitis[6,7]. Since Banks first reported the migration of this class of surgical clip into the bladder after LRP in 2008[8], such related adverse events for HOLC have gradually increased in the urinary system. In addition, the majority of reported complications with HOLC are urethral erosion, bladder neck contracture, and subsequent stone formation[8-10], but they were finally visualized and removed by endoscopy.

The collecting system migration of suture material post-LPN has also been reported. Park et al[11] reported a case of ureteral migration of a HOLC two years after laparoscopic right partial nephrectomy, and it was removed by using a ureteroscopic stone basket device. Dasgupta reported a HOLC that migrated into the renal pelvis, with renal calculus formation following laparoscopic dismembered pyeloplasty within a few weeks[12], and a similar case was also reported 6 years after retroperitoneoscopic left pelvilithotomy[13]. In both reported cases, the HOLC was removed by percutaneous nephroscopy. With the increasing deployment of HOLC, similar complications have also appeared in robotic surgery. Blumenthal and his colleague[9] reported the first case of HOLC migration into the vesicourethral anastomosis and urethra after RALRP (robot assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy), while Yadav et al[14] presented a HOLC that migrated into the subrenal calyx of the left kidney, presenting as a renal stone, which was employed to close the mesenteric window that formed during bilateral robotic pyeloplasty .

Unfortunately, clips consisting of differing materials cannot avoid similar situations. Miller et al[15] reported that Lapra-Ty absorbable suture clips (Ethicon EndoSurgery) migrated from a laparoscopic partial nephrectomy bed into the collecting system 6 wk after LPN, causing renal colic. Massoud[16] also reported that a metal surgical clip was displaced into the ureter after open partial nephrectomy (OPN), all of which was passed spontaneously. Furthermore, in the urologic literature, it has been reported that surgical clips, and even absorbable gastrointestinal staples, can act as a nidus for stone formation when in contact with urine[17]. Msezane et al[18] reviewed differing sealants and laparoscopic instruments that can be used to stop bleeding of the renal parenchyma within LPN and concluded that there is no gold-standard single agent or combination of products that can be applied to all cases. A combined approach, utilizing manual suturing and hemostatic technology, may be the best strategy to achieve hemostasis.

Although there existed non-common cases related to HOLC migrating into the renal pelvis with renal calculus formation, it is unclear how a HOLC become dislodged and migrated into the collecting system. According to the surgical experience of this case four years ago, we analyzed that the persistent tensile force of the suture line may facilitate HOLC migration into the renal pelvis from the fissure at the ureteropelvic junction before the sutures were absorbed and embedded, and it can act as a nidus for stone formation when in contact with urine for extended time periods. By reviewing related case reports of laparoscopic surgery in the renal pelvis or collecting system, we believe that the use of HOLC instead of traditional knots - when suturing incisions in the renal pelvis or collecting system - leads to a higher risk of HOLC migration. However, more research must be performed to uncover how and why HOLC migrates into the collection system.

Due to the limitation of warm ischemia time in partial nephrectomy, HOLC can be used for vascular pedicle control or rapid suture stabilization, and there is no better substitute presently. Therefore, risk reduction for this rare complication is still a present challenge. Surgical or endoscopic removal of the foreign body is mandatory, in view of the high complication rate and significant clinical symptoms. Several previous reports include the removal of foreign bodies by percutaneous nephrostomy or endoscopic maneuvers. But prevention of HOLC migration is clearly better than complication treatments, so the surgeon must be aware of the possibility of clip migration. Meanwhile, all loose clips should be actively sought and retrieved from the wound during urinary system surgery, and the use of clips in close proximity to the anastomotic stoma of collecting systems should also be avoided.

In summary, we conclude that in order to prevent complications related to HOLC, loose clips should be actively sought and retrieved from the wound during urinary system surgery, and the use of clips in close proximity to the anastomotic stoma of collecting systems should be avoided.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tustumi F S-Editor: Zhang YL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Baumert H, Ballaro A, Arroyo C, Kaisary AV, Mulders PF, Knipscheer BC. The use of polymer (Hem-o-lok) clips for management of the renal hilum during laparoscopic nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2006;49:816-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van Ophoven A, deKernion JB. Clinical management of foreign bodies of the genitourinary tract. J Urol. 2000;164:274-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ballesteros Sampol JJ, Alameda Quitllet F, Parés Puntas ME. [3 rare cases of textiloma after renal surgery. Review of the literature]. Arch Esp Urol. 2002;55:25-29. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bellin M, Hornoy B, Richard F, Davy-Miallou C, Fadel Y, Zaim S, Challier E, Grenier P. Perirenal textiloma: MR and serial CT appearance. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:57-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Coelho RF, Mitre AI, Srougi M. Intrarenal foreign body presenting as a renal calculus. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2007;62:527-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rajendra A, Cohen SA, Kasmin FE, Siegel JH, Leitman M. Surgical clip migration and stone formation in a gallbladder remnant after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:780-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sheffer D, Gal O, Ovadia B, Kopelman Y. Cholangitis caused by surgical clip migration into the common bile duct: a rare complication of a daily practice. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Banks EB, Ramani A, Monga M. Intravesical Weck clip migration after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2008;71:351.e3-351.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Blumenthal KB, Sutherland DE, Wagner KR, Frazier HA, Engel JD. Bladder neck contractures related to the use of Hem-o-lok clips in robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2008;72:158-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tunnard GJ, Biyani CS. An unusual complication of a Hem-o-Lok clip following laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:649-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park KS, Sim YJ, Jung H. Migration of a Hem-o-Lok Clip to the Ureter Following Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy Presenting With Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Int Neurourol J. 2013;17:90-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dasgupta R, Hannah K, Glass J. Case report: percutaneous nephrolithotomy for a stone on a Hem-o-lok clip. J Endourol. 2008;22:463-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang K, Jiang ZQ. Hem-o-lok: A Nonignorable Cause of Severe Renal Calculus with Intrapelvic Migration. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016;129:1003-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yadav S, Singh P, Nayak B, Dogra PN. Unusual cause of renal stone following robotic pyeloplasty. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Miller M, Anderson JK, Pearle MS, Cadeddu JA. Resorbable clip migration in the collecting system after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Urology. 2006;67:845.e7-845.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Massoud W. Spontaneous migration of a surgical clip following partial nephrectomy. Urol J. 2011;8:153-154. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Gronau E, Pannek J. Reflux of a staple after kock pouch urinary diversion: a nidus for renal stone formation. J Endourol. 2004;18:481-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Msezane LP, Katz MH, Gofrit ON, Shalhav AL, Zorn KC. Hemostatic agents and instruments in laparoscopic renal surgery. J Endourol. 2008;22:403-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |