Published online Apr 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3170

Peer-review started: July 17, 2021

First decision: November 11, 2021

Revised: November 12, 2021

Accepted: February 22, 2022

Article in press: February 22, 2022

Published online: April 6, 2022

Processing time: 255 Days and 3.2 Hours

To the best of our knowledge, cases of Kawasaki disease (KD) occurring at the age of 12 are rare, even in Asia where the incidence of KD is high. We report a case of lymph-node-first presentation of KD (NFKD) in a 12-year-old girl with Myco

A previously healthy 12-year-old girl presented with fever, myalgia, sore throat, swelling, and tenderness on the right side of the neck. She was initially diagnosed with lymphadenitis caused by M. pneumoniae refractory to macrolide antibiotics. She had elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels. Finally, the patient was diagnosed with KD. After receiving intravenous immunoglobulin, the fever resolved, and her symptoms improved.

NFKD should be differentiated from adolescent lymphadenitis presenting with prolonged fever by checking the BNP level early.

Core Tip: We report the case of a 12-year-old girl with lymphadenitis caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae refractory to macrolide antibiotics. The fever persisted, and the patient did not respond to macrolide (clarithromycin) administered for 72 h. The brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level, additionally measured to diagnose atypical Kawasaki disease (KD), was 427.2 ng/mL. A slight QT interval prolongation and a dilated right coronary artery were detected. She was finally diagnosed with lymph-node-first presentation of KD. Even if adolescent lymphadenitis with confirmed bacterial or viral infection does not have other symptoms of KD, early measurement of BNP levels can help diagnose KD.

- Citation: Kim N, Choi YJ, Na JY, Oh JW. Lymph-node-first presentation of Kawasaki disease in a 12-year-old girl with cervical lymphadenitis caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(10): 3170-3177

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i10/3170.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3170

Kawasaki disease (KD) is a self-limiting systemic inflammatory condition that occurs predominantly in infants and young children aged ≤ 5 years[1]. The etiologic agents causing KD are yet to be identified. Various bacterial and viral agents have been suggested to be associated with KD, but none is responsible for it. Therefore, the diagnosis is based on characteristic clinical manifestations[1,2]. Cases involving fewer than four clinical features are referred to as atypical KD, which makes the diagnosis difficult, and the incidence of such cases is increasing[3,4]. Cases of cervical lymphadenopathy with fever are also common, accounting for 9%-23% of all cases[5,6]. Patients with cervical lymphadenopathy as the first symptom are consider to have a node-first presentation of KD (NFKD)[7-9].

Pediatric patients with NFKD are often incorrectly diagnosed with bacterial cervical lymphadenitis (BCL) early after onset, which delays the diagnosis of KD and, consequently, delays proper treatment[5,9]. There are many known causes of BCL, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae) is one of the causative pathogens. M. pneumoniae is commonly known to be a major causative agent of primary atypical pneumonia, with symptoms that are similar to those of KD, which causes difficulty in differential diagnosis in the beginning[10].

We report a case of NFKD of the lymph node in a 12-year-old girl who was undergoing treatment for cervical lymphadenitis caused by M. pneumoniae. The age of 12 years is not the prevalent age for KD, and KD occurring in 12-year-old children is very rare, even in Asia where the incidence rate is high. In addition, the patient did not present with typical symptoms of KD.

A previously healthy 12-year-old girl presented to our hospital with fever, myalgia, sore throat, swelling, and tenderness on the right side of the neck on August 27, 2018.

She had fever, sore throat, and severe swelling of the left cervical lymph node (LN) for 4 d before hospital presentation. Furthermore, she had severe pain and tenderness in the swollen neck, which also limited the neck movement. As the fever worsened, she underwent treatment with antibiotics (amoxicillin) and antipyretics (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen) at a local clinic. However, the symptoms did not improve; thus, she was referred to a general hospital. She was hospitalized on fever day 4.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. Her physical and neurological developments were normal.

Family and genetic history of the patient was unremarkable.

The patient’s height and weight were 152.7 cm and 41.5 kg, respectively. Her vital signs at admission were as follows: body temperature, 39 °C; blood pressure, 100/60 mmHg; heart rate, 96 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 99% at room air. She was alert, but looked ill and dehydrated. At the time of admission, she had severe left neck swelling and pain, which hindered her from moving her neck to the left. Other than the red tonsils, she had no other notable symptoms, such as red lips, strawberry tongue, conjunctival infection, rash, and edema of the hands and feet.

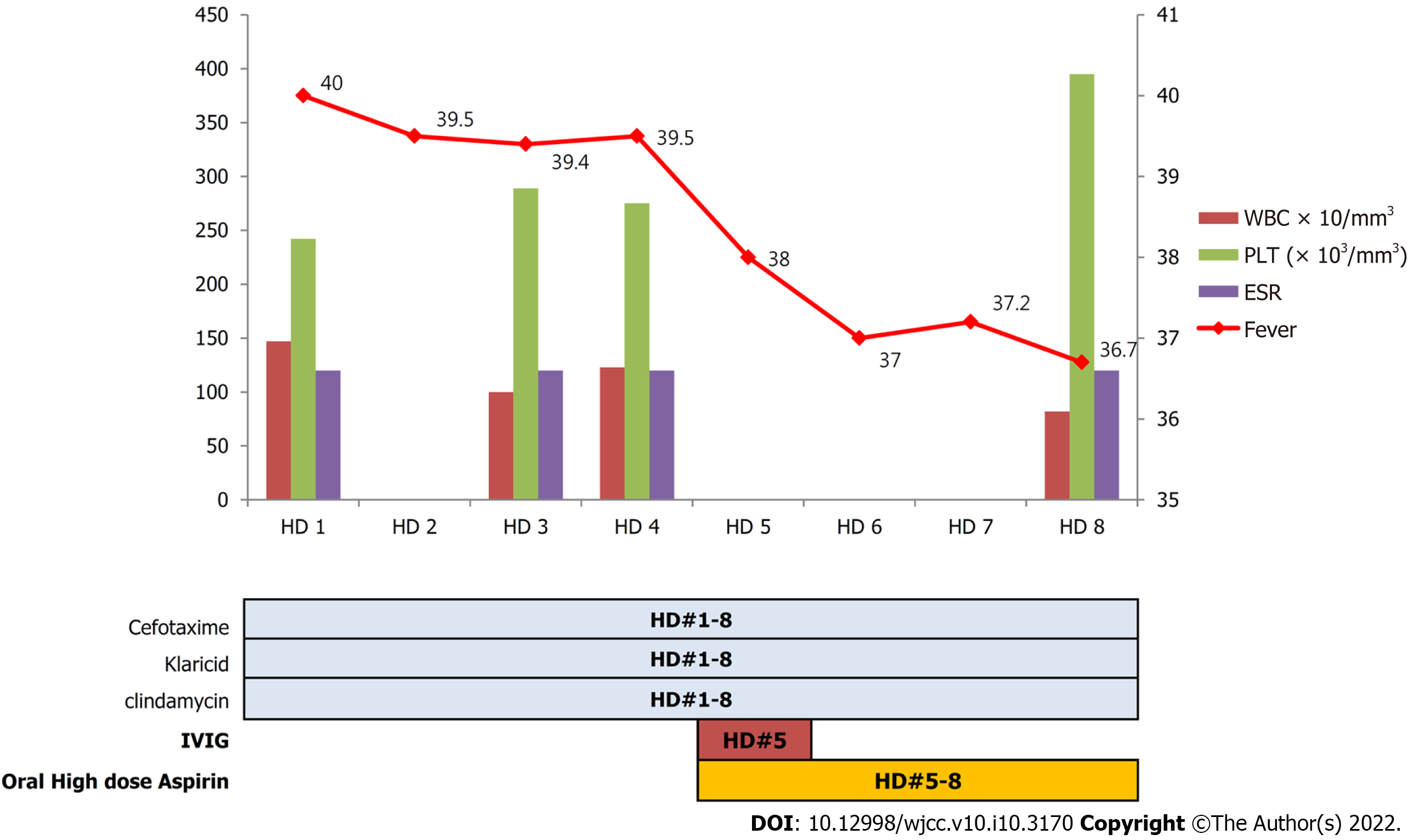

Serum laboratory results showed elevated white blood cell count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP) level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and liver enzyme level, which were as follows: WBC count, 14.7 × 103/mm3; hemoglobin, 11.5 g/dL; platelet count, 242 × 103/mm3; ESR, 120 mm/h; CRP, 6.44 mg/dL; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 459 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 650 U/L; and total bilirubin, 0.9 mg/dL. Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time were within normal ranges. Urinary analysis results were normal. There was no pyuria. She tested negative for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis virus, and respiratory virus. However, she tested positive for MP immunoglobulin M (IgM), with an index of 13. The results of MP are expressed as an index (ratio between the optical density of the test sample and that of the cut-off value) that could be used as a quantitative measure, as it is proportional to the amount of specific IgM present. The test serum is considered positive when the ratio is > 10[10].

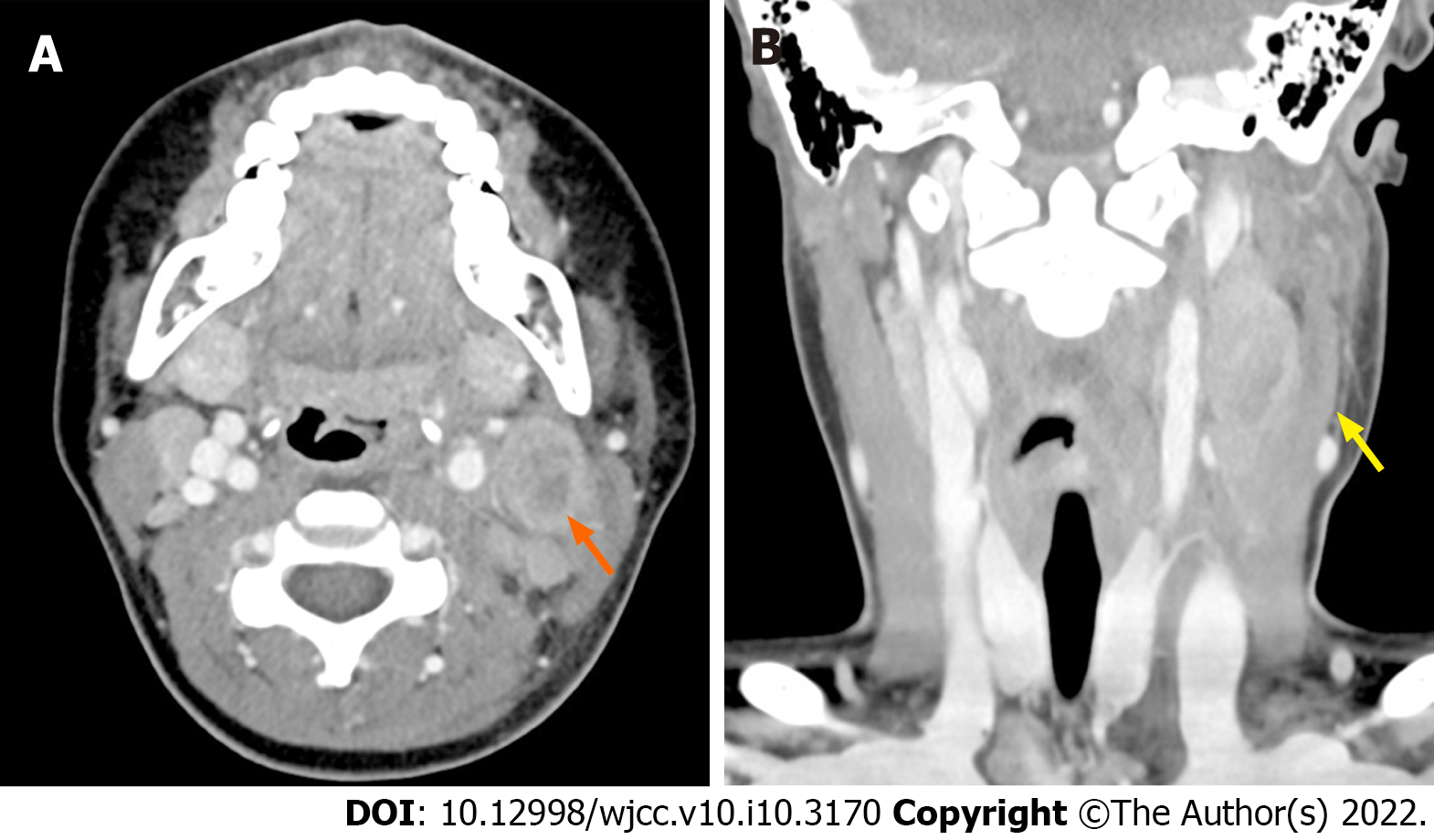

Neck computed tomography (CT) revealed a 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm × 3.2 cm acute infectious lymphadenitis with perilesional infiltration and necrosis (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with lymphadenitis caused by MP (Mycoplasma IgM ratio: 13).

She was treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics [third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime 150 mg/kg/d) + macrolide (clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/d) + clindamycin (full gram 25 mg/kg/d)] and silymarin (legalon 70 mg/d) on the first day of hospitalization.

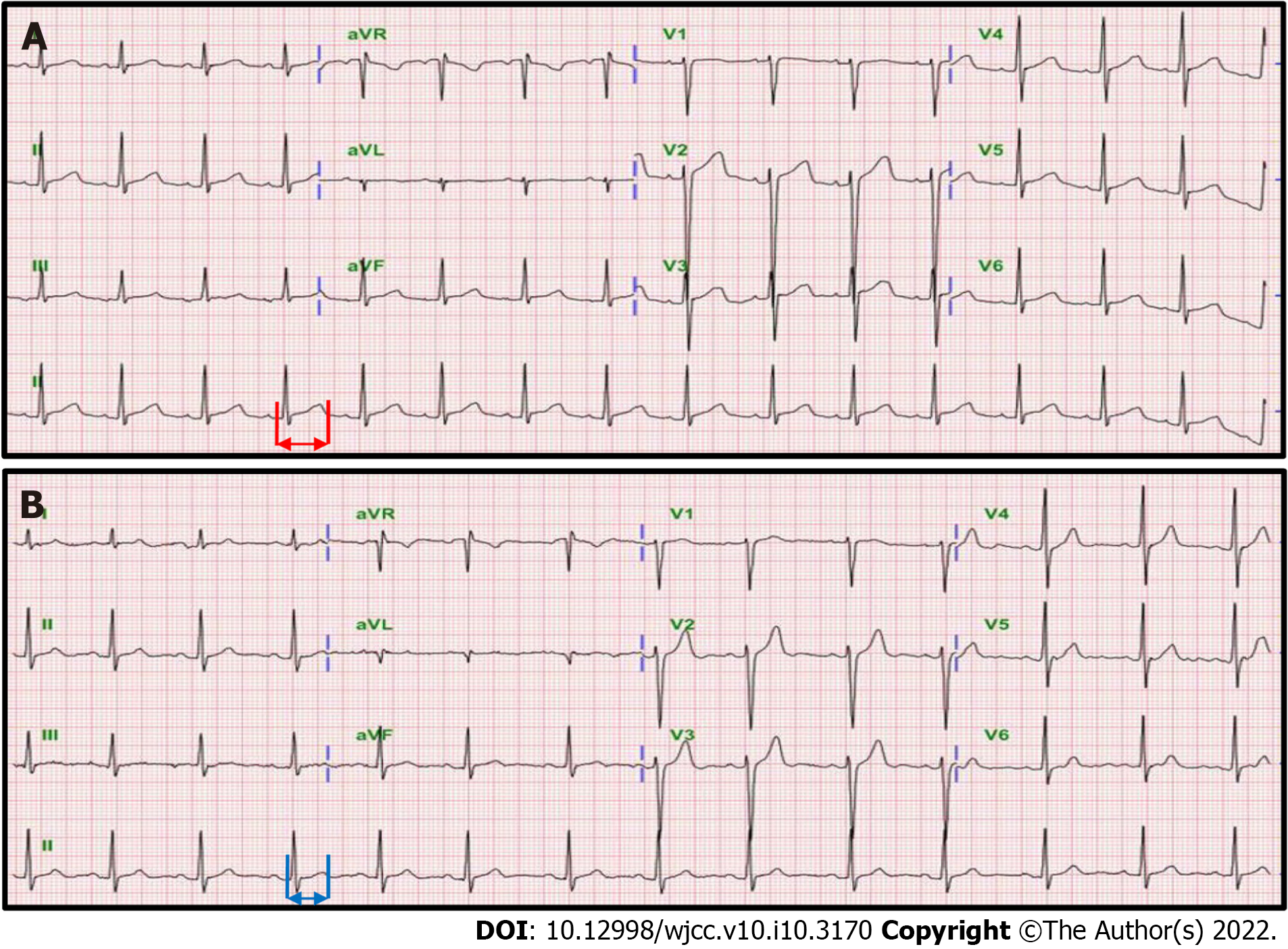

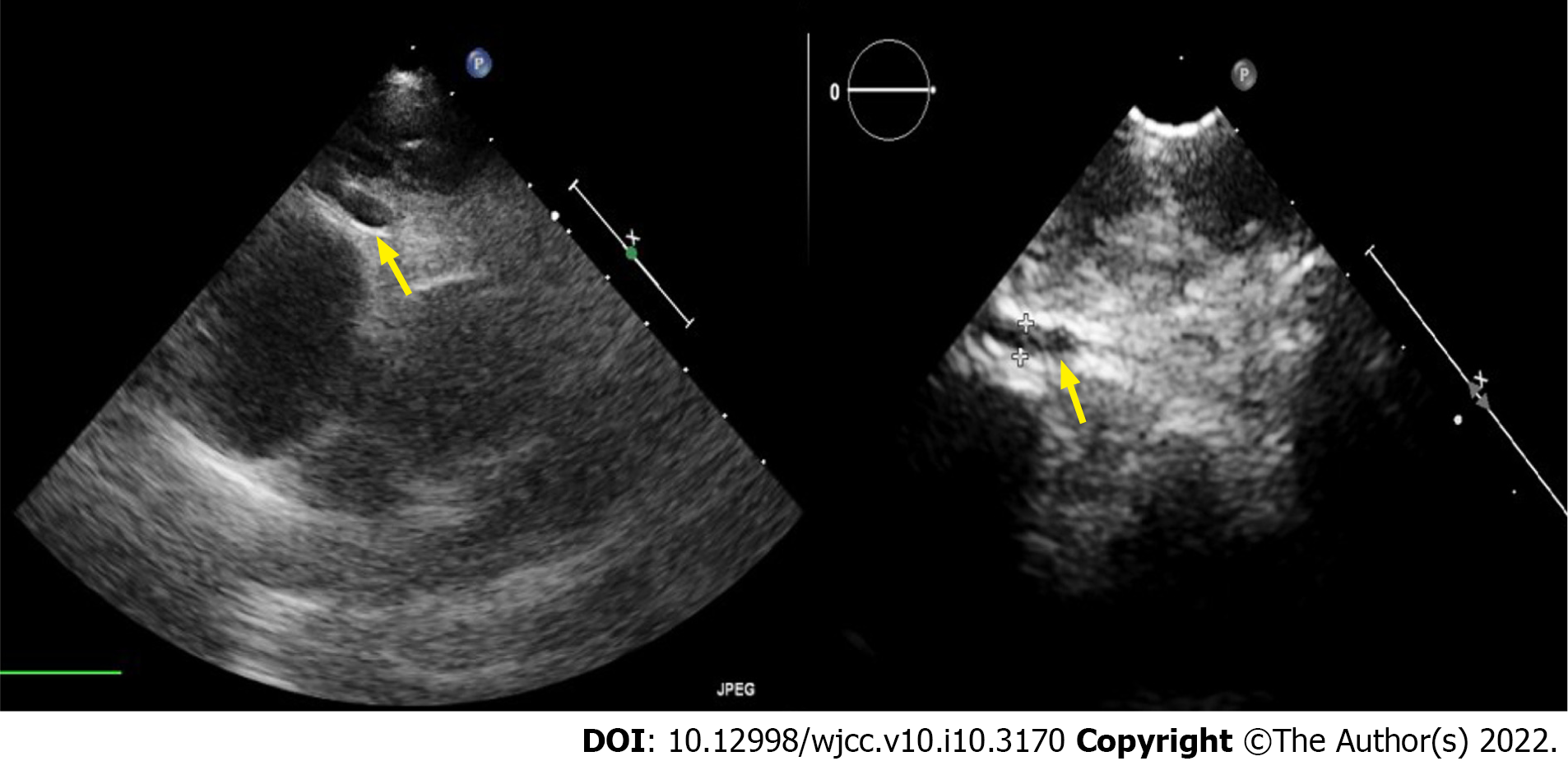

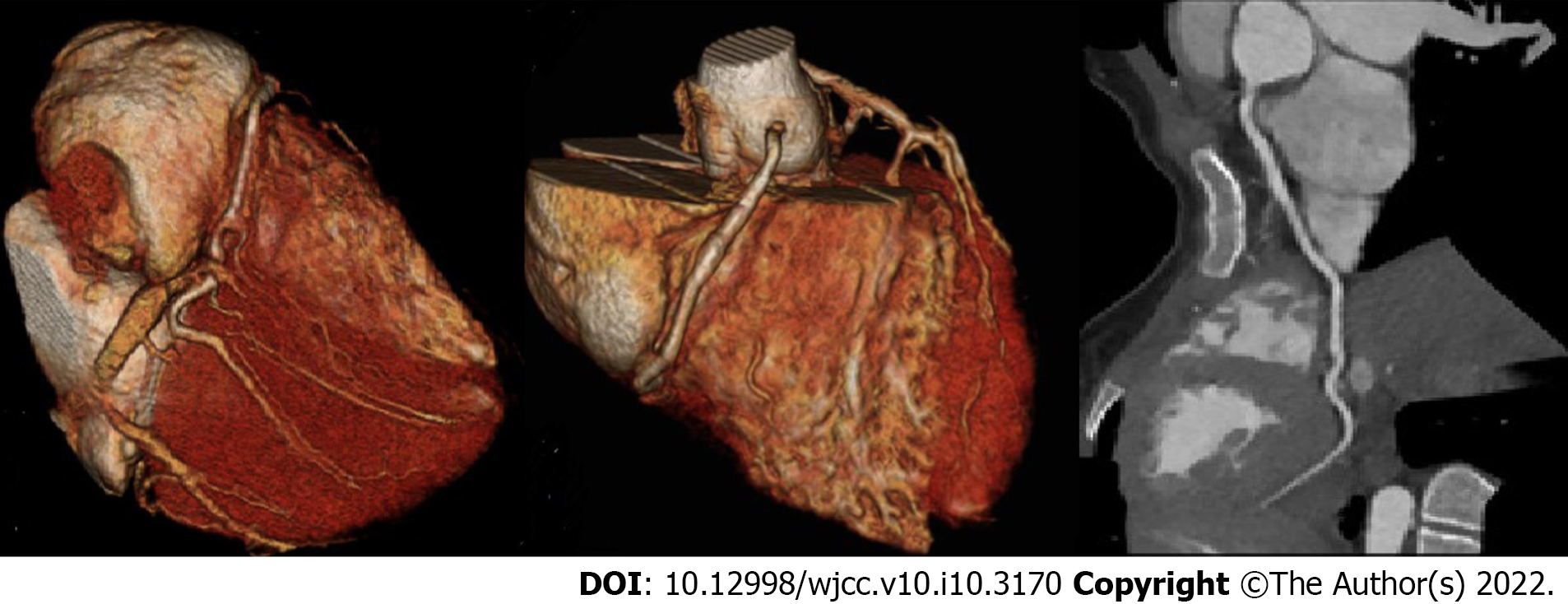

On hospital day 3, the test results showed mild improvement, with CRP level of 5.71 mg/dL and AST and ALT levels of 85 U/L and 198 U/L, respectively. However, the fever, cervical edema, severe pain, and tenderness persisted without improvement. On hospital day 4, the fever persisted (day 8 of fever) and the patient had very slight conjunctival hyperemia in the morning. The patient did not respond to macrolide (clarithromycin) administered for 72 h. Therefore, we suspected a refractory MP infection. We also measured the brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level to diagnose atypical KD because of the slight conjunctival hyperemia. The BNP level was 427.2 ng/mL (normal: < 100 ng/mL). Additional cardiac work-up included an echocardiography (ECG), which showed a slight QT interval prolongation (corrected QT interval: 489 ms) (Figure 2A) and a dilated right coronary artery (RCA diameter; 4.73 mm, Z score: 4.62, by Boston method) and left coronary artery [LCA diameter; 2.35 mm, Z score: -1.73, (Boston method); Figure 3]. Cardiac CT, performed to accurately evaluate the degree of coronary artery dilatation, revealed a multifocal ectatic change of the entire RCA (Figure 4).

Finally, the patient was diagnosed with NFKD. The patient’s fever subsided on the second day of treatment, and her general condition, symptoms, and laboratory findings gradually improved.

A new treatment was initiated. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG; 2 g/kg/d) and oral high-dose aspirin (50 mg/kg/d) were administered 5 d post-admission and 10 d after the onset of fever. Lymphedema, pain, and tenderness improved 3 d after IVIG treatment. On hospital day 8, the patient recovered and was discharged from the hospital. After discharge, the patient was placed on maintenance therapy with low-dose aspirin (5 mg/kg/d).

ECG performed at 1 mo after discharge showed improvement, with an RCA diameter of 3.40 mm (Z score= 1.68) and an LCA diameter of 0.26 mm (Z score: -1.17) by the Boston method; ECG performed 3 mo later showed further improvement, with an RCA diameter of 2.32 mm (Z score: -0.72 mm), an LCA diameter of 2.90 mm (Z score: -0.64), and a normal QT interval (0.36 s). Two months later, the ESR improved to 20 mm/h (Figure 5). At the 2-year follow-up evaluation, she remained healthy without any sequelae, including a normal QT interval (Figure 2B), and all blood test results showed normal findings.

We present the case of a 12-year-old female adolescent who was diagnosed with KD while undergoing treatment for fever and LN swelling.

Given that the patient was 12 years old, an age that is beyond the common age of onset of KD, and was confirmed to have MP infection, we had initially excluded the possibility of LN swelling caused by KD and we treated the patient only for MP-induced cervical lymphadenitis. Eventually, the fever persisted, and after measuring the BNP level on day 9 of fever, we diagnosed the patient with NFKD and began treatment accordingly.

MP is known to produce superantigens, and various studies have reported MP as a KD-causing agent[11-15]. A case of cutaneous vasculitis induced by MP, through immune-complex-mediated mechanisms, has been reported[15]. In Perez et al[16]’s study, 12 of 54 (22.2%) patients with concurrent KD and pneumonia had anti-MP antibody titers ≥ 1:640. MP infection is highly correlated with KD induction. Therefore, it is essential to consider KD as an accompanying disease or a differential diagnosis in cases of MP infection[17,18].

Some studies have shown that the time of receiving the initial IVIG treatment was significantly later in incomplete KD cases than in complete KD cases (median: 7 d from the onset of fever in incomplete KD vs 5 d from the onset of fever in complete KD)[19]. Compared to these cases, the patient in the present case had a delayed diagnosis. The patient also had cardiovascular complications, such as QT prolongation and coronary artery dilatation, at the time of diagnosis.

Due to the growing number of reports of atypical KD that do not satisfy the conventional diagnostic criteria, clinicians have strived to diagnose atypical KD in a timely manner[20]. Atypical KD frequently affects infants aged < 1 year[20]. According to some reports, the incidence of major clinical symptoms of KD, with the exception of oral mucosal changes, was significantly lower in atypical KD than in typical KD, with the former having the lowest incidence of cervical lymphadenopathy and atypical rash[21-23].

Atypical KD, which has attracted much interest in recent years, occurs in young patients and more often shows oral erythema, compared to LN swelling. Therefore, it is difficult to suspect KD in NFKD cases occurring in older adolescent patients with a confirmed case of infection and only LN swelling presentation, such as in our case[21,22].

One previous study reported that patients with NKFD frequently develop cardiovascular complications and have delayed IVIG treatment and that NFKD itself may be a risk factor for cardiovascular complications[5-7,23,24]. The reason for this is that delayed diagnosis and treatment, as shown in our case, lead to fever persisting for a prolonged period and may cause coronary artery complications[24].

The main goal of the diagnosis and treatment of KD is to prevent coronary artery complications that can cause myocardial infarction or sudden death. Given that using IVIG early after onset can reduce the incidence of such serious complications, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for NFKD[24,25]. Yanagi et al[8] reported that the levels of leukocytes, absolute neutrophils, CRP, and AST were higher in the NFKD group than in the BCL group. However, in Kanegaye et al[6]’s study, the ESR and the levels of CRP, blood pigment, platelets, ALT, and gamma-glutamyl transferase also showed significant differences between the two groups. Several studies have suggested that early BNP testing is useful for the early differentiation of NFKD from BCL[25,26]. Based on these findings, it will be helpful to measure BNP levels in the early stages of cervical lymphadenitis in patients with persistent fever that does not respond to antibiotic treatment. Moreover, measuring BNP levels at an early stage in patients with fever and LN swelling and in cases in which cardiac evaluation is difficult would be conducive for an early diagnosis of NFKD.

We report this case to show that the occurrence of NFKD is possible even in adolescents aged ≥ 10 years who are being treated for a confirmed infection due to a different bacterial pathogen, such as MP, with fever only, which persists for > 5 d, and LN swelling.

Clinicians should always consider the possibility of NFKD when making a differential diagnosis in pediatric patients with LN swelling and fever that persist for > 5 d and who do not respond to general antibiotics, even when the patient is older than the age group commonly affected by KD. Prompt diagnosis and timely initiation of IVIG are crucial for KD, because if diagnosed later, patients may have serious heart complications. Moreover, BNP levels should be measured early for this purpose.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pan H, Srivastava D S-Editor: Zhang YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Rogers MF, Kochel RL, Hurwitz ES, Jillson CA, Hanrahan JP, Schonberger LB. Kawasaki syndrome. Is exposure to rug shampoo important? Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:777-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim GB, Park S, Eun LY, Han JW, Lee SY, Yoon KL, Yu JJ, Choi JW, Lee KY. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Kawasaki Disease in South Korea, 2012-2014. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:482-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, Baker AL, Jackson MA, Takahashi M, Shah PB, Kobayashi T, Wu MH, Saji TT, Pahl E; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927-e999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1586] [Cited by in RCA: 2435] [Article Influence: 304.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Thapa R, Chakrabartty S. Atypical Kawasaki disease with remarkable paucity of signs and symptoms. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:1095-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nomura Y, Arata M, Koriyama C, Masuda K, Morita Y, Hazeki D, Ueno K, Eguchi T, Kawano Y. A severe form of Kawasaki disease presenting with only fever and cervical lymphadenopathy at admission. J Pediatr. 2010;156:786-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kanegaye JT, Van Cott E, Tremoulet AH, Salgado A, Shimizu C, Kruk P, Hauschildt J, Sun X, Jain S, Burns JC. Lymph-node-first presentation of Kawasaki disease compared with bacterial cervical adenitis and typical Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2013;162:1259-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stamos JK, Corydon K, Donaldson J, Shulman ST. Lymphadenitis as a dominant manifestation of Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 1994;93: 525-528. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Yanagi S, Nomura Y, Masuda K, Koriyama C, Sameshima K, Eguchi T, Imamura M, Arata M, Kawano Y. Early diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in patients with cervical lymphadenopathy. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kao HT, Huang YC, Lin TY. Kawasaki disease presenting as cervical lymphadenitis or deep neck infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:468-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim S, Um TH, Cho CR. Evaluation of chorus mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM assay for the serological diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Lab Med Qual Assur. 2012;34:57-62. |

| 11. | Martire B, Foti C, Cassano N, Buquicchio R, Del Vecchio GC, De Mattia D. Persistent B-cell lymphopenia, multiorgan disease, and erythema multiforme caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:558-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Christie J. Diagnosing Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children and adolescents with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Nurs. 2013;113:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Narita M, Yamada S, Nakayama T, Sawada H, Nakajima M, Sageshima S. Two cases of lymphadenopathy with liver dysfunction due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection with mycoplasmal bacteraemia without pneumonia. J Infect. 2001;42:154-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Romero-Gómez M, Otero MA, Sánchez-Muñoz D, Ramírez-Arcos M, Larraona JL, Suárez García E, Vargas-Romero J. Acute hepatitis due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection without lung involvement in adult patients. J Hepatol. 2006;44:827-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Daxboeck F, Gattringer R, Mustafa S, Bauer C, Assadian O. Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients with serologically verified Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:507-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Perez C, Montes M. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis and encephalitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:352-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang JN, Wang SM, Liu CC, Wu JM. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection associated with Kawasaki disease. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:594-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vitale EA, La Torre F, Calcagno G, Infricciori G, Fede C, Conti G, Chimenz R, Falcini F. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: a possible trigger of kawasaki disease or a mere coincidental association? Minerva Pediatr. 2010;62:605-607. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Sudo D, Monobe Y, Yashiro M, Mieno MN, Uehara R, Tsuchiya K, Sonobe T, Nakamura Y. Coronary artery lesions of incomplete Kawasaki disease: a nationwide survey in Japan. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:651-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gandhi A, Wilson DG. Incomplete Kawasaki disease: not to be forgotten. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:276-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Luo ZM, Fan YH, Liu DS. Early diagnosis and clinical features of incomplete Kawasaki disease in children. J Appl Clin Pediatr. 2011;26:671-673. |

| 22. | Gupta K, Rohit M, Sharma A, Nada R, Jain S, Varma S. An Adolescent with Kawasaki Disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Burns JC, Shike H, Gordon JB, Malhotra A, Schoenwetter M, Kawasaki T. Sequelae of Kawasaki disease in adolescents and young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang RL, Lo HH, Lei C, Ip N, Chen J, Law BY. Current pharmacological intervention and development of targeting IVIG resistance in Kawasaki disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2020;54:72-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shiraishi M, Fuse S, Mori T, Doyama A, Honjyo S, Hoshino Y, Hoshino E, Kawaguchi A, Kuroiwa Y, Hotsubo T. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic Peptide as a useful diagnostic marker of acute Kawasaki disease in children. Circ J. 2013;77:2097-2101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | McNeal-Davidson A, Fournier A, Spigelblatt L, Saint-Cyr C, Mir TS, Nir A, Dallaire F, Cousineau J, Delvin E, Dahdah N. Value of amino-terminal pro B-natriuretic peptide in diagnosing Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Int. 2012;54:627-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |