Published online Apr 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3078

Peer-review started: September 29, 2021

First decision: December 17, 2021

Revised: December 24, 2021

Accepted: February 15, 2022

Article in press: February 15, 2022

Published online: April 6, 2022

Processing time: 183 Days and 4.1 Hours

Radical resection is the only indicator associated with survival in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHCC). However, limited data are available regarding the implications of dysplasia at the resection margin following surgery.

To evaluate the prognostic significance of dysplasia-positive margins in patients diagnosed with EHCC.

We reviewed the records of patients who had undergone surgery for EHCC with curative intent between January 2013 and July 2017. We retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathological data of 116 patients followed for longer than 3 years. The status of resection margin was used to classify patients into negative low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/carcinoma in situ (CIS) categories.

Based on postoperative status, 72 patients underwent resection with negative margins, 19 had LGD-positive margins, and 25 showed HGD/CIS-positive margins. The mean survival rates of the patients with negative margins, LGD margins, and HGD/CIS margins were 49.1 ± 4.5, 47.3 ± 6.0, and 20.8 ± 4.4 mo, respectively (P < 0.001). No difference in survival was found between groups with LGD margins and negative margins (P = 0.56). In the multivariate analysis, age > 70 years and HGD/CIS-positive margins were significant independent factors for survival (hazard ratio = 1.90 and 2.47, respectively).

HGD/CIS margin in resected EHCC is associated with a poor survival. However, the LGD-positive resection margin is not a significant indicator of survival in patients with EHCC.

Core Tip: This study indicated that the status of the bile duct resection margin in operable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHCC) is an important indicator of recurrence and survival. High-grade dysplasia/carcinoma in situ margin in resected EHCC was associated with a poor survival and high tumor recurrence. However, low-grade dysplasia positive margin was not a significant prognostic factor in patients with EHCC.

- Citation: Choe JW, Kim HJ, Kim JS. Significance of dysplasia in bile duct resection margin in patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A retrospective analysis. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(10): 3078-3087

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i10/3078.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i10.3078

The incidence of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHCC) is increasing worldwide due to the advances in diagnostic modalities and increased life expectancy[1]. Despite multidisciplinary management, only 20% of these patients are eligible for surgical resection, and the disease is associated with a poor prognosis and a 5-year overall survival of less than 10%[2]. Even though surgical resection for EHCC has been performed more frequently in recent years, the prognosis is still dismal because of frequent recurrence in R1 (microscopic residual tumor) resection margins[3,4]. The status of bile duct resection margin is the most important indicator of recurrence and survival, and a carcinoma-negative margin is the only factor associated with survival[5-7].

However, ensuring an adequate resection margin is still a challenge due to perioperative morbidity associated with extensive surgical procedures. Biliary malignant disease occurs mainly in elderly patients, who represent a unique surgical category because of the higher risk of postoperative complications. Several newly published studies indicate that high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and carcinoma in situ (CIS) of the biliary duct margin are not independent prognostic factors for disease-specific survival in patients with operable EHCC, unlike invasive carcinoma margin[8]. Further, additional resection failed to improve the prognosis when the margin was HGD/CIS[8]. The significance of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) at the resection margin in EHCC is unclear. The clinical relevance of dysplasia in resection margins remains largely unknown.

Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate the prognostic impact of dysplasia-positive margins on EHCC.

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 116 consecutive patients who had undergone curative surgery for EHCC at two tertiary academic centers, Korea University Ansan Hospital and Guro Hospital, from January 2013 to July 2017. The study included the clinicopathological data of patients identified from a database over more than 3 years. We defined EHCC as distal common bile duct (CBD) cancer, proximal CBD cancer, or common hepatic duct (CHD) cancer/Klatskin tumor. We excluded patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or cancers of the gallbladder or ampulla of Vater, and patients with a history of chronic biliary diseases, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune-related cholangiopathy, or invasive carcinoma arising from intraductal papillary neoplasm. This study did not include patients diagnosed with invasive carcinoma at the resection margin during the final pathologic review or those who had undergone surgery with palliative intention. Most patients underwent preoperative biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice, and surgical resection was performed to secure a negative proximal margin with curative intent. Not all patients underwent additional resection surgery. Each patient’s past medical history was reviewed for previous cancer treatment and comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes mellitus (DM), liver cirrhosis (LC), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary heart disease, or human immunodeficiency virus infection. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Guro Hospital (2021AS0282).

During the pathological analysis, the status of the resection margin was classified into negative (negative for carcinoma or dysplasia), LGD-positive, and HGD/CIS types. We excluded margins with invasive carcinoma. Since it was extremely difficult to distinguish between HGD and CIS, we combined them into the HGD/CIS group in this study[9]. In most cases, histological examination of resection margin was performed by a gastrointestinal pathologist. In case of ambiguous histological findings, the final results were reported after discussion with other pathologists.

We divided the patients into two groups based on age: > 70 and ≤ 70 years. Given the peak incidence of ECC between 50 and 70 years of age, this study defined elderly patients as those above 70 years of age[10]. The overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of the hospital visit to the last follow-up date or the date of death. Operation-related mortality was defined as death on the day of surgery in the hospital.

The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival according to the status of the resection margin in patients who underwent surgery with curative intent. The secondary endpoints were tumor recurrence rate depending on the resection margin and risk factors for overall survival.

Fisher’s exact test or chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. Quantitative variables and treatment endpoints were analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis test. Kaplan-Meier curves were used for survival analysis, and the differences were assessed using log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression analyses were used to evaluate the prognostic factors for survival. All results were considered significant at a P value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (Version 20.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

We enrolled a total of 116 patients who had been followed for more than 3 years after curative surgery. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean patient age was 69.7 ± 8.8 years (range, 50-91 years), and 50.9% (59/116) were elderly patients > 70 years of age. Forty-one patients (35%) manifested chronic comorbidities, such as CKD, DM, LC, and COPD. Surgery with curative intent was performed in 51 patients with distal CBD cancer, 43 with proximal CBD cancer, and 22 with Klatskin tumor. Preoperative bile drainage was performed in 95.7% of enrolled patients. Endoscopic bile drainage was used in 78% of cases and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was used in 22%. Seventy-two patients underwent curative resection with R0 margins, while 44 patients had R1 (microscopic residual tumor)-positive resection margins. Of the 44 patients with positive margins, 19 carried LGD-positive margins, and 25 showed HGD/CIS-positive margins. In the elderly patients, 33 patients had R0 resection margin, whereas 9 had LGD margin, and 17 showed HGD/CIS margin. The operations most commonly performed were pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) or Whipple operation involving 70 patients. Perineural invasion and lymphatic invasion were detected in 41 and 81 cases, respectively. Moderate differentiation was most commonly identified. Postoperative mortality occurred in ten patients including eight elderly cases, due to surgical complications. Adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy was administered to 46 patients, depending upon clinician’s discretion considering lymph node status and resection margin.

| Baseline characteristics | |

| Age (yr, ≤ 70/ > 70) | 57/ 59 |

| Gender (female/male) | 49/ 67 |

| Comorbidity (-/+) | 75/ 41 |

| Location of tumor (distal CBD/proximal CBD/CHD or Klatskin tumor) | 51/43/22 |

| Preoperative drainage | |

| None | 5 |

| Endoscopic bile drainage | 87 |

| PTBD | 24 |

| Resection margin | |

| Negative | 72 |

| LGD positive | 19 |

| HGD/CIS positive | 25 |

| T stage (T1/2/3/4) | 42/ 49/ 25/ 0 |

| N stage (0/1) | 82/ 34 |

| Perineural invasion (-/+) | 41/ 75 |

| Lymphatic invasion (-/+) | 81/ 35 |

| Differentiation (well/ moderate/ poor) | 18/ 72/ 26 |

| CA 19-9 (≤ 37/> 37) | 44 / 72 |

| Op method | |

| BDR | 24 |

| PPPD or Whipple operation | 70 |

| BDR + hepatectomy | 19 |

| BDR+ PPPD or Whipple + hepatectomy | 3 |

| Adjuvant therapy (-/+) | 70 / 46 |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| Recurrence rate | 63 (54.3) |

| Time from operation to recurrence | 13 mo |

| Op related death | 10 (8.6) |

| ≤ 70 years old: 2/ 57 (3.5) | |

| > 70 years old: 8/ 59 (13.6) | |

| Mortality | 77 (66.4) |

| Cancer related mortality | 65/ 77(84.4) |

| Overall survival (mean) | 44.2 ± 3.43 mo |

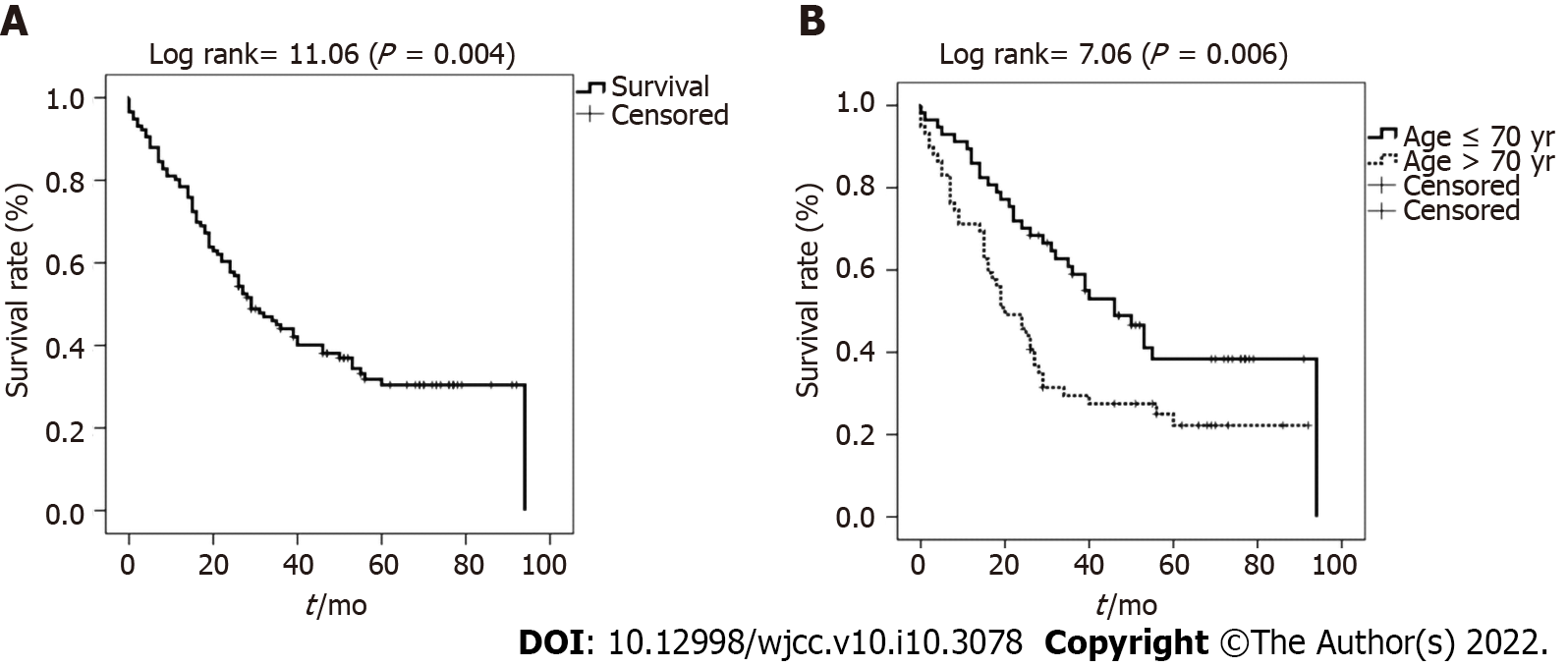

The mean OS in all patients was 44.2 ± 3.4 mo [95% confidence interval (CI): 37.5–55.9 mo] (Figure 1A). The mean survival of patients in the > 70-year-old group was 34.7 ± 4.4 mo, which was significantly poorer than that of patients belonging to the ≤ 70-year-old group (53.3 ± 4.9 mo; P = 0.006) (Figure 1).

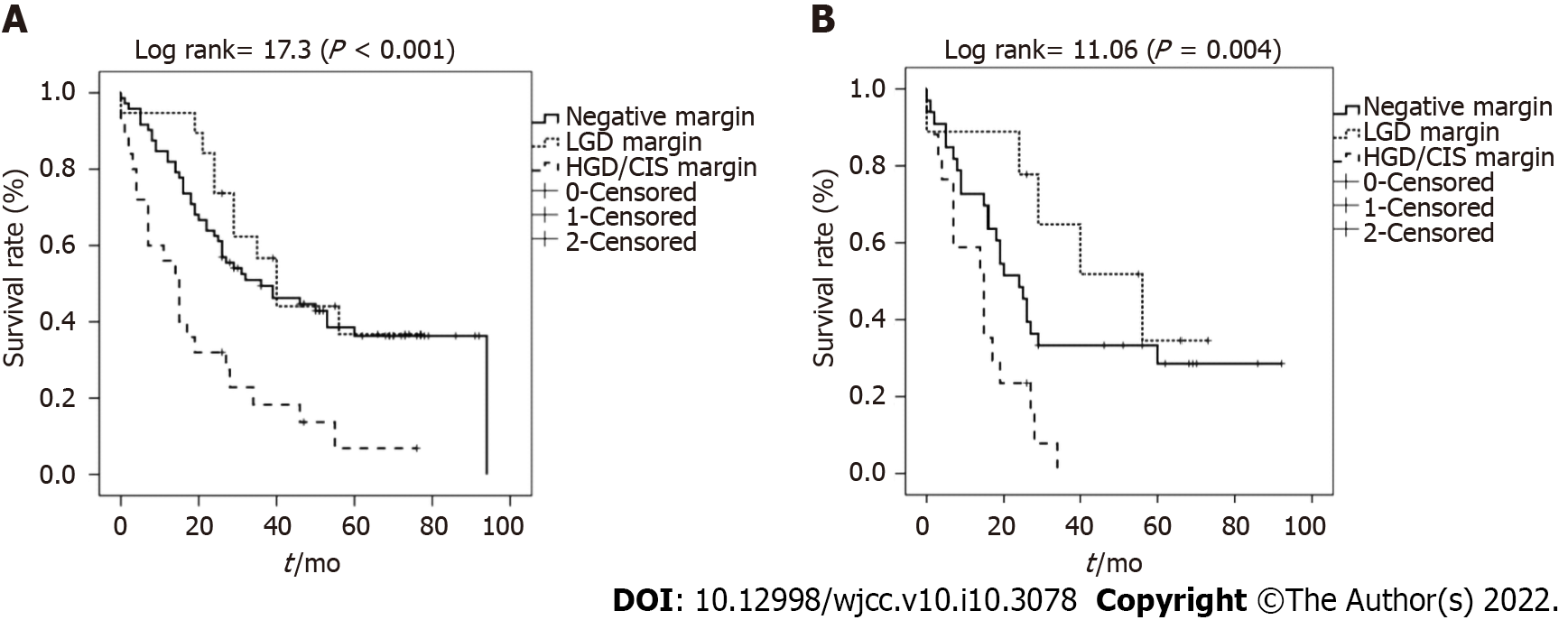

The mean survival rates of patients with negative resection margins, LGD margins, and HGD/CIS margins were 49.1 ± 4.5, 47.3 ± 6.0, and 20.8 ± 4.4 mo, respectively. Also, the median survival was 36.0 (15.6-56.4), 40.0 (30.7-49.3), and 29.0 (10.2-36.8) mo, respectively (P < 0.001) (Figure 2A). The survival of patients in the HGD/CIS-positive margin group was significantly less than that of patients with negative margins and LGD margins. Patients with LGD margins showed an OS similar to that of the negative margin group (P = 0.56).

In the elderly patients, the mean survival of those with negative margins, LGD margins, and HGD/CIS margins were 39.0 ± 6.3, 46.5 ± 8.5, and 14.3 ± 2.6 mo, respectively (P = 0.004) (Figure 2B). Patients with LGD margins showed a better cumulative survival without statistical significance than those with a negative margin (P = 0.280).

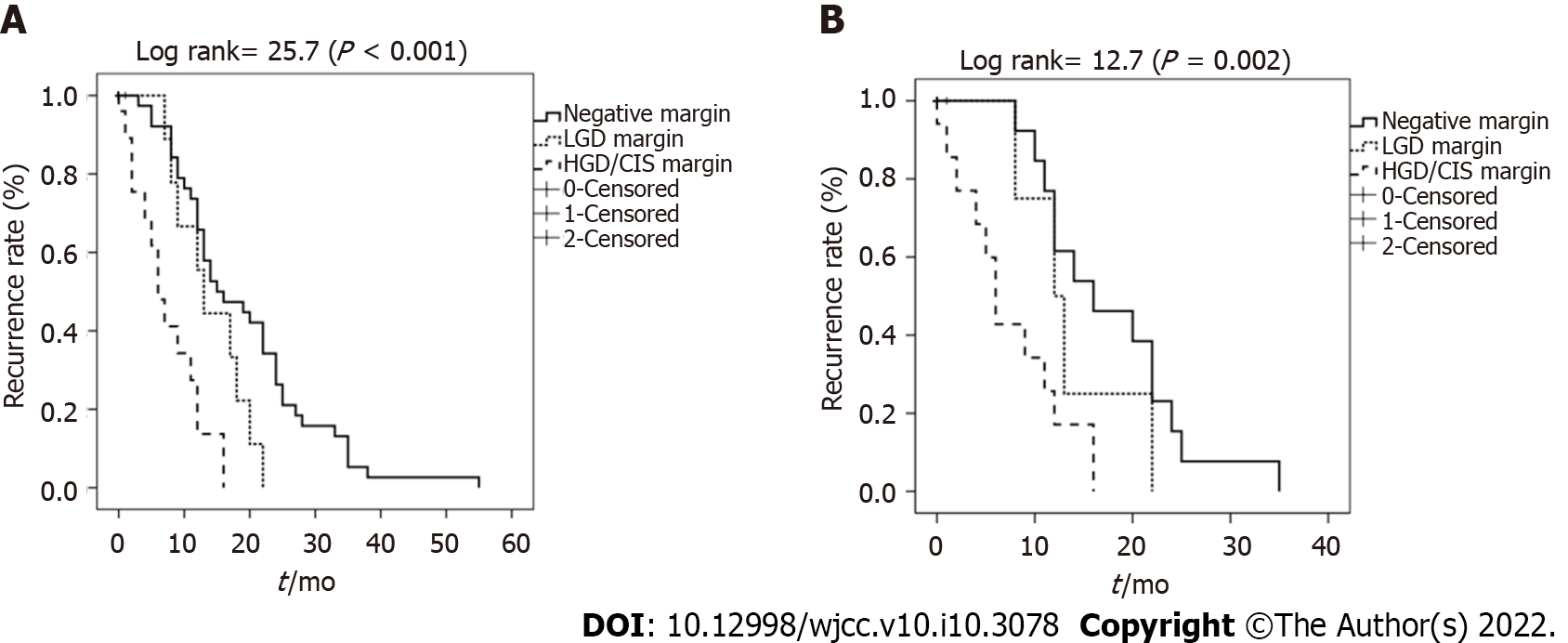

Based on the analysis of patients’ resection margin, the rates of tumor recurrence associated with negative margin, LGD margin, and HGD/CIS margin were 47.2% (34/72), 52.6% (10/19), and 76.0% (19/25), respectively. Based on the resection margin of all patients, the actual probability of negative-from-tumor recurrence differed significantly between patients with HGD/CIS margins and the others (P < 0.001) (Figure 3A). Patients with negative resection margins showed a tendency towards lower rates of tumor recurrence compared with those carrying LGD dysplasia margins. However, no statistical difference was observed (P = 0.07).

This trend was also seen in elderly patients. The rates of tumor recurrence in patients with negative margins, LGD margins, and HGD/CIS margins were 39.4% (13/33), 44.4% (4/9), and 70.6% (12/17), respectively. The actual probability of negative-from-tumor recurrence in elderly patients also differed significantly according to resection margin status (P = 0.002) (Figure 3B). However, there was no statistically significant difference between patients with negative resection margins and those with LGD dysplasia margins (P = 0.32).

The univariate analysis of risk factors for survival revealed that age above 70 years, CHD or Klatskin tumor, extensive operation (combined with bile duct resection and PPPD/Whipple operation and hepatectomy), and HGD/CIS-positive margins were significantly independent risk factors. Adjuvant therapy was the only significant factor, which independently improved survival in the univariate, but not in multivariate analysis (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, old age and HGD/CIS-positive margins were significant factors associated with OS (hazard ratio = 1.9 and 2.47, respectively). Comorbidity was not a significant factor for survival. N stage, lymphatic invasion, and differentiation were also not significant factors.

| Univariate analysis for overall survival | ||

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (> 70 yr old) | 1.98 (1.21–3.23) | < 0.01 |

| Gender (female) | 1.18 (0.37–3.72) | 0.32 |

| Location of tumor | 0.02 | |

| distal CBD | 1 | |

| prox. CBD | 0.32 (0.10–1.02) | 0.06 |

| CHD or Klatskin tumor | 3.73 (0.69–20.2) | 0.13 |

| Op method | 0.35 | |

| BDR | 1 | |

| PPPD or Whipple operation | 1.09 (0.97- 1.23) | 0.42 |

| BDR + hepatectomy | 1.88 (0.28-12.63) | 0.51 |

| BDR+ PPPD or Whipple + hepatectomy | 19.35 (2.78-134.64) | < 0.01 |

| Resection margin | < 0.01 | |

| Negative | 1 | |

| LGD positive | 0.83 (0.42-1.63) | 0.58 |

| HGD/CIS positive | 7.72 (1.04-57.52) | 0.001 |

| T stage | 0.283 | |

| T1 | 1 | |

| T2 | 0.95 (0.15-5.94) | 0.105 |

| T3 | 1.53 (0.82-3.14) | 0.283 |

| N stage | ||

| N(-) | 1 | |

| N(+) | 1.31 (0.96-2.54) | 0.120 |

| Perineural invasion | 1.28 (0.8-2.1) | 0.329 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 1.13 (0.7-1.9) | 0.624 |

| Differentiation | 1.16 (0.5-2.6) | 0.814 |

| Well | 1 | |

| Moderate | 0.73 (0.20-2.63) | 0.625 |

| Poor | 2.07 (0.50-8.56) | 0.317 |

| CA 19-9 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.592 |

| Comorbidity | 1.38 (0.92-2.21) | 0.173 |

| History of malignancy | 0.88 (0.4-1.8) | 0.707 |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.31 (0.11-0.86) | 0.024 |

| Multivariate analysis for overall survival | ||

| Age (≥ 70 yr old) | 1.9 (1.2-3.1) | 0.01 |

| HGD/CIS positive margin | 2.47 (1.4-4.2) | 0.002 |

In this study, we evaluated the prognostic value of margin in resected EHCC. We further investigated the clinical importance of the resection margin for EHCC in elderly patients via subgroup analysis because of relative variation in major comorbidities and higher perioperative morbidities associated with old age. The prognostic factors for resected EHCC were also analyzed.

Currently, the therapeutic gold standard for EHCC is complete surgical tumor resection or curative resection, defined as histologically cancer-free resection margin[11]. Positive resection margins are considered as the most powerful risk factor for tumor recurrence and survival. However, the use of an aggressive approach to obtain negative resection margins might be controversial and depends on patient's status including potential morbidity and oncologic outcomes following resection. It is hard to decide whether or not aggressive and extensive resection is warranted in elderly patients, because of the higher risk of postoperative complications. Until recently, most studies divided positive margin status into two histological subtypes: Invasive carcinoma and HGD/CIS. Several reports of invasive carcinoma-positive margins suggest a strong adverse effect on patient survival and tumor recurrence[3,12,13]. Few studies involved HGD/CIS, but reported varying results[13,14]. Further, few studies have explored the significance of LGD in surgical EHCC margin until now. However, LGD and HGD/CIS are frequently found in postoperative bile duct margins, but the clinical significance remains unclear.

In the present study, patients with resection margins containing HGD/CIS had significantly worse survival outcomes than those with negative or LGD resection margins. However, patients with LGD-positive margins showed mean survivals similar to those with negative resection margins. Regarding HGD/CIS margins, the results are consistent with several other studies showing a poor prognosis as well as high tumor recurrence rate in the HGD/CIS group when compared with the negative resection margin group[15,16]. Even after adjusting for age that strongly influenced the prognosis, HGD/CIS-positive resection margin was a significant prognostic factor in this study. However, a recently published meta-analysis comparing the HGD/CIS margin group and negative margin group reported that HGD/CIS of the biliary duct margin did not affect the prognosis of patients with operable EHCC[14]. Some studies reported that additional resection to achieve negative margins did not improve the prognosis when the margin revealed HGD/CIS[17,18]. However, the effect of HGD/CIS margins on survival was different between patients with early stages of EHCC (defined as patient with pathologic N0M0 or T1/T2 or negative lymph node) and those with an advanced stage of EHCC[8,14,16]. HGD/CIS margins in early-stage EHCC patients were associated with a significantly increased incidence of local recurrence, as well as shorter survival, when compared with those carrying negative margins, suggesting that HGD/CIS should be avoided as often as possible during surgery for early-stage EHCC. In our study, a worse prognosis in the HGD/CIS group than in the negative margin group could be explained by the early stages in most patients: T stage 1 or 2 (78.4%, 91/116) and without lymph node (70.7%, 82/116).

To date, no study has evaluated the resection margins with LGD in EHCC. In this study, the survival and recurrence rate were comparable between patients with LGD margins and negative margins. Further, the LGD group in the subgroup analysis of elderly patients showed a better survival time and cumulative survival rate than those with negative margins due to the following reasons: (1) The extent of surgery was greater in the negative margin group of elderly patients than in the LGD group of elderly patients. The ratio of patients undergoing hepatectomy to those without hepatectomy was lower in the elderly LGD group (0/9) than in the negative margin group (6/33); (2) operation-related death occurred in five cases of the negative resection margin group. Otherwise, there was no perioperative mortality event in the LGD margin group, which suggests a longer mean survival time in the LGD group; and (3) despite limited evidence of benefits associated with adjuvant therapy in patients with resected EHCC with a dysplasia margin, adjuvant therapy was performed more frequently in the LGD group. Considering that old age and HGD/CIS were independent factors associated with a poor survival in patients with EHCC, LGD-positive resection margin in elderly patients is a reasonable parameter for determining the negative resection margin. In contrast, the HGD/CIS margin group clearly showed higher recurrence and poorer survival rates compared with other LGD margin and negative margin groups. The prognosis in patients with HGD/CIS margins can be improved, but it is difficult to establish a consensus regarding the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation treatment for the HGD/CIS patient group because postoperative adjuvant therapy was performed according to the clinician's decision and the patient's condition. Furthermore, the duration of chemotherapy in the patient, the dose of chemotherapy, and the chemotherapy regimen were varied without specific criteria. Therefore, a comparative study involving a large number of patients with HGD/CIS is needed to establish the benefits of adjuvant therapy in the future.

The study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective study involving a limited number of patients, especially patients with LGD resection margins. Second, the follow-up period was not adequate to determine delayed recurrence and survival time. Third, missing confounding factors, such as surgical technique and patient’s financial condition, also play a role. Therefore, further studies involving a large number of patients are needed to develop a guideline for dysplasia-positive margins in patients with EHCC.

In conclusion, the HGD/CIS margin in resected EHCC is associated with a poor survival and high tumor recurrence. However, the LGD-positive margin is not a significantly poor prognostic factor in patients with EHCC.

The status of the bile duct resection margin in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (EHCC) is the most important indicator of recurrence and survival.

There is a lack of information regarding the meaning of dysplasia at the resection margin in EHCC. The clinical relevance of dysplasia in resection margins remains largely unknown, and no consensus has been reached.

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of dysplasia-positive margins as a prognostic indicator in patients with EHCC.

A total of 116 patients who had undergone surgery for EHCC with curative intent were enrolled in this study. Curative resection with free margins was achieved in 72 patients, while 44 patients had microscopic residual tumor at resection margins. Of the 44 patients, 19 carried low-grade dysplasia (LGD)-positive margins, and 25 showed high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/carcinoma in situ (CIS)-positive margins.

The mean survival rates of the patients with negative margins, LGD margins, and HGD/CIS margins were 49.1 ± 4.5, 47.3 ± 6.0, and 20.8 ± 4.4 mo, respectively (P < 0.001). There was no difference in survival between groups with LGD margins and negative margins (P = 0.56).

HGD/CIS margin in resected EHCC is associated with a poor survival and high tumor recurrence. However, LGD-positive margin is not a significantly poor prognostic factor in patients with EHCC.

This study provides meaningful information to establish a guideline for dysplasia-positive margins in patients with EHCC.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huang Y, Meglio LD, Sano W S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Khan SA, Tavolari S, Brandi G. Cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology and risk factors. Liver Int. 2019;39 Suppl 1:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 80.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang J, Obulkasim H, Zou XP, Liu BR, Wu YF, Wu XY, Ding YT. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by liver transplantation is a promising treatment for patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case report. Oncology Letters 2019; 17(2): 2069-2074. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tang Z, Yang Y, Zhao Z, Wei K, Meng W, Li X. The clinicopathological factors associated with prognosis of patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Komaya K, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, Mizuno T, Yamaguchi J, Nagino M. Recurrence after curative-intent resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of a large cohort with a close postoperative follow-up approach. Surgery. 2018;163:732-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shingu Y, Ebata T, Nishio H, Igami T, Shimoyama Y, Nagino M. Clinical value of additional resection of a margin-positive proximal bile duct in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 2010;147:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sasaki R, Takeda Y, Funato O, Nitta H, Kawamura H, Uesugi N, Sugai T, Wakabayashi G, Ohkohchi N. Significance of ductal margin status in patients undergoing surgical resection for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2007;31:1788-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ueda J, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Yoshioka M, Hirakata A, Kawano Y, Mizuguchi Y, Shimizu T, Kanda T, Takata H, Kondo R, Uchida E. Evaluation of positive ductal margins of biliary tract cancer in intraoperative histological examination. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:6677-6684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Higuchi R, Yazawa T, Uemura S, Izumo W, Furukawa T, Yamamoto M. High-grade dysplasia/carcinoma in situ of the bile duct margin in patients with surgically resected node-negative perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is associated with poor survival: a retrospective study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:456-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shiraki T, Kuroda H, Takada A, Nakazato Y, Kubota K, Imai Y. Intraoperative frozen section diagnosis of bile duct margin for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1332-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15395] [Article Influence: 2565.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Yoo T, Park SJ, Han SS, Kim SH, Lee SD, Kim TH, Lee SA, Woo SM, Lee WJ, Hong EK. Proximal Resection Margins: More Prognostic than Distal Resection Margins in Patients Undergoing Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma Resection. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:1106-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shirai Y, Sakata J, Wakai T, Hatakeyama K. Intraoperative assessment of the resectability of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2436-2438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bird NTE, McKenna A, Dodd J, Poston G, Jones R, Malik H. Meta-analysis of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2018;105:1408-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ke Q, Wang B, Lin N, Wang L, Liu J. Does high-grade dysplasia/carcinoma in situ of the biliary duct margin affect the prognosis of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma? World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Han IW, Jang JY, Lee KB, Kang MJ, Kwon W, Park JW, Chang YR, Kim SW. Clinicopathological analysis and prognosis of extrahepatic bile duct cancer with a microscopic positive ductal margin. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tsukahara T, Ebata T, Shimoyama Y, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, Mizuno T, Nagino M. Residual Carcinoma In Situ at the Ductal Stump has a Negative Survival Effect: An Analysis of Early-stage Cholangiocarcinomas. Ann Surg. 2017;266:126-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park Y, Hwang DW, Kim JH, Hong SM, Jun SY, Lee JH, Song KB, Jun ES, Kim SC, Park KM. Prognostic comparison of the longitudinal margin status in distal bile duct cancer: R0 on first bile duct resection vs R0 after additional resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26:169-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wakai T, Sakata J, Katada T, Hirose Y, Soma D, Prasoon P, Miura K, Kobayashi T. Surgical management of carcinoma in situ at ductal resection margins in patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2:359-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |