Published online Jan 7, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.51

Peer-review started: January 28, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: July 11, 2021

Accepted: November 22, 2021

Article in press: November 22, 2021

Published online: January 7, 2022

Processing time: 335 Days and 22.7 Hours

An incisional hernia is a common complication of abdominal surgery.

To evaluate the outcomes and complications of hybrid application of open and laparoscopic approaches in giant ventral hernia repair.

Medical records of patients who underwent open, laparoscopic, or hybrid surgery for a giant ventral hernia from 2006 to 2013 were retrospectively reviewed. The hernia recurrence rate and intra- and postoperative complications were calculated and recorded.

Open, laparoscopic, and hybrid approaches were performed in 82, 94, and 132 patients, respectively. The mean hernia diameter was 13.11 ± 3.4 cm. The incidence of hernia recurrence in the hybrid procedure group was 1.3%, with a mean follow-up of 41 mo. This finding was significantly lower than that in the laparoscopic (12.3%) or open procedure groups (8.5%; P < 0.05). The incidence of intraoperative intestinal injury was 6.1%, 4.1%, and 1.5% in the open, laparoscopic, and hybrid procedures, respectively (hybrid vs open and laparoscopic procedures; P < 0.05). The proportion of postoperative intestinal fistula formation in the open, laparoscopic, and hybrid approach groups was 2.4%, 6.8%, and 3.3%, respectively (P > 0.05).

A hybrid application of open and laparoscopic approaches was more effective and safer for repairing a giant ventral hernia than a single open or laparoscopic procedure.

Core Tip: This retrospective study reviewed patients with giant ventral hernias who received operations from 2006 to 2013. The outcomes and complications of three commonly used techniques for giant ventral hernia repair were compared. A hybrid approach combining laparoscopic and open procedures is an effective method for giant ventral hernia repair. It is associated with low complication rates and hernia recurrence. Hybrid repair combines the advantages of laparoscopic and open repair and minimizes the disadvantages of the two approaches.

- Citation: Yang S, Wang MG, Nie YS, Zhao XF, Liu J. Outcomes and complications of open, laparoscopic, and hybrid giant ventral hernia repair. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(1): 51-61

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i1/51.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.51

An incisional hernia is a common complication of abdominal surgery. It has an incidence of 9%–20% at 1 year of follow-up[1]. Fink et al[2] reported an incidence of incisional hernia of 22.4% in 755 cases of laparotomy at 3 years compared to 12.6% at 1 year after the procedure[2]. These findings indicate an increasing incidence of incisional hernia over time. A giant incisional hernia (> 10 cm in diameter) is normally treated with a prosthetic mesh using an open procedure[3,4]. This procedure is associated with a large amount of tissue dissection, extensive postoperative complications, long hospitalization, and lengthy recovery[5].

Incisional hernia repair with a laparoscopic approach has been advocated for approximately two decades and is characterized by minimal trauma, fast recovery, and short hospitalization[3]. A wide and clear visual field assists adhesion separation and examination of the abdominal wall defect[5]. However, laparoscopic closure is slightly difficult due to the suture technique, suture type, and increased abdominal wall tension caused by the pneumoperitoneum[6]. General laparoscopic repair requires a V-Loc suture, which increases treatment costs and is not widely used in China. Furthermore, the postoperative occurrence of seroma and hernia recurrence is high in both open and laparoscopic hernia repair[6], particularly in laparoscopic repair of giant abdominal hernias[7]. There is currently no consensus for the management of giant ventral hernias; nevertheless, several new methods have been proposed[8-10].

The hybrid application of open and laparoscopic procedures has been increasingly attempted for giant ventral hernia repair. In 2000, Lowe et al[11] proposed an endoscopy-assisted procedure for abdominal wall defect repair[11]. Sharma et al[12] subsequently argued that a limited-conversion technique offered a safe and viable alternative in laparoscopic incisional hernia repair in patients with a bowel-incarcerated hernia sac or requiring extensive adhesiolysis[12]. Other studies revealed that a hybrid technique (laparoscopy with an additional open procedure using only a small incision) reduced the incidence of postoperative complications in patients with giant ventral hernias[13,14]. Griniatsos et al[15] reported a hybrid technique for recurrent incisional hernia repair[15]. Stoikes et al[16] proposed that the hybrid approach could be used in obese patients requiring open adhesiolysis during incisional hernia repair[16]. However, the outcomes and operative complications of hybrid approaches have not been compared with the single application of an open or laparoscopic approach. This study retrospectively reviewed patients with giant ventral hernias who underwent surgery from 2006 to 2013 and compared the outcomes and complications of the three commonly used techniques for giant ventral hernia repair.

The medical records of adult patients (> 18 years of age) who underwent giant ventral hernia repair at the Department of Hernia and Abdominal Wall, Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China, from January 2006 to June 2013, were retrospectively reviewed.

Adolescents < 18 years were excluded because they are still in the growth and development phase. Also, the use of synthetic materials can result in complications. Thus, the institution of this study prohibits the use of artificial materials in persons < 18 years.

A preoperative computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was performed in all patients to diagnose the hernia and evaluate the hernia characteristics. A giant ventral hernia was defined as a hernia defect with a diameter ≥ 10 cm. The hernias were classified based on the 29th Congress of the European Hernia Society[3]. Patients with a giant ventral hernia, who received a planned hernia repair procedure, open, laparoscopic, or hybrid, were included in the analysis. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The presence of skin ulceration or infection; (2) The use of anticoagulants or high-dose hormones within 4 wk before the procedure (anticoagulants can result in bleeding and may affect hematoma formation; hormones can affect the immune system and alter postoperative changes of inflammatory mediators); (3) Participation in other clinical studies within 3 mo before the procedure; (4) A history of atopic allergy; (5) Major mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, severe anxiety, or depression); (6) Conditions that can significantly increase intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., ascites associated with liver cirrhosis, cough from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and intractable constipation); (7) Infection at the operative site or bacteremia; and (8) Patients requiring emergency surgery (e.g., bowel strangulation).

The local Ethics Review Boards of Chao-Yang Hospital approved the study protocol. All procedures were performed following established European and American guidelines for hernia repair, and all patients provided written informed consent for all procedures performed.

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia by surgeons with a minimum of 10 years of experience repairing ventral hernias by open and laparoscopic approaches.

Open and laparoscopic repairs were performed using the intraperitoneal onlay mesh technique. Composix E/X mesh (15.5 cm × 20.5 cm to 20 cm × 30 cm; Davol Inc., Warwick, RI, United States) was used for hernia repair. Every patch was extended 5 cm beyond the exterior margin of the inner defect and was fixed to the abdominal wall. In the open procedures, the mesh was fixed with an abdominal wall suturing device (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland). A full-thickness abdominal wall penetrating hanging suturing line (single polypropylene suture) was fixed at the 12 or 10 o’clock position. The mesh patch was fixed in the laparoscopic group at one central and two side points using an abdominal wall hanging penetrating suture. The surrounding area and edge were fixed with laparoscopic tacks. The basic principle was that the distance between tacks was not < 3 cm.

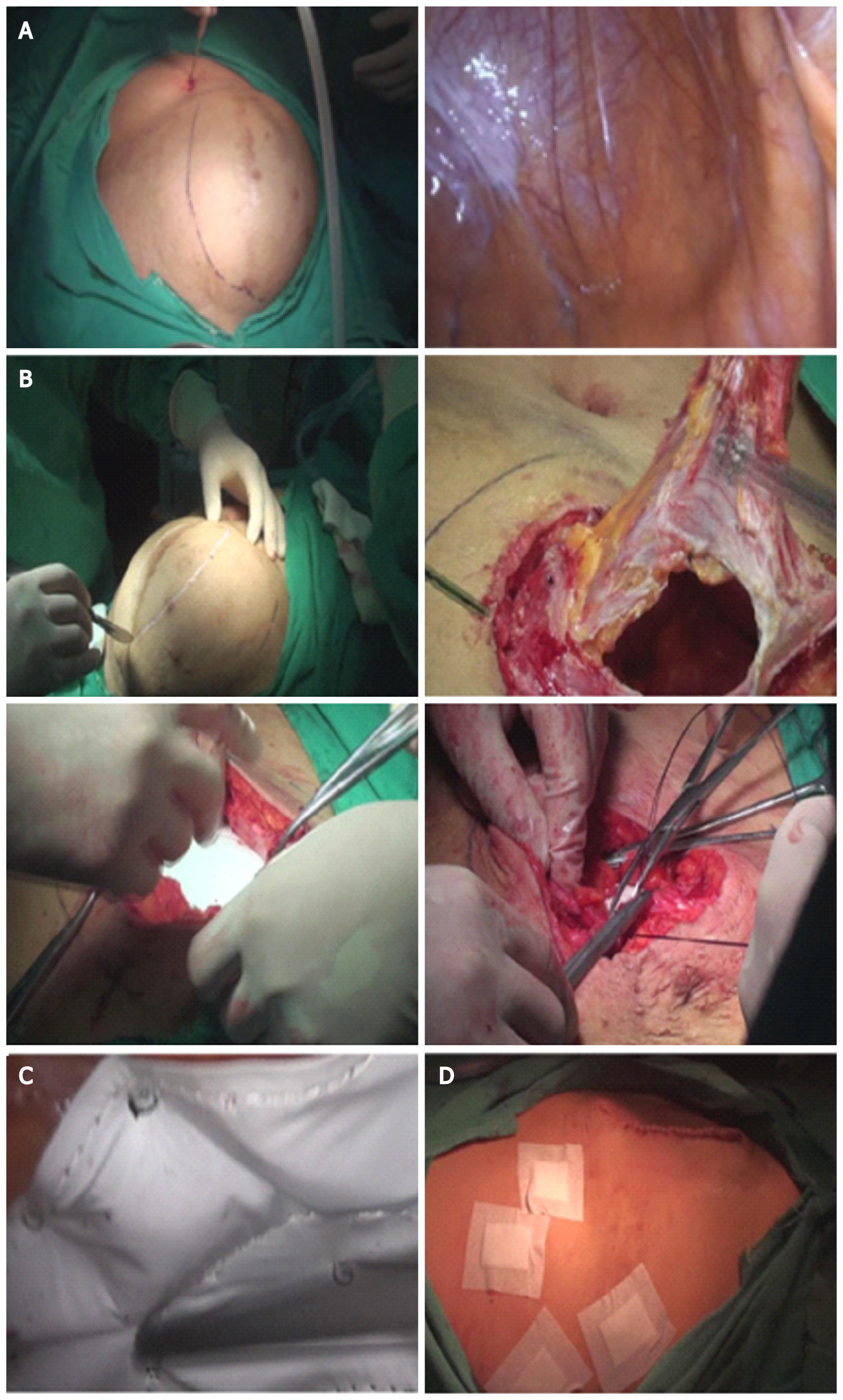

The treatment of abdominal hernias using the hybrid method explored and separated the intra-abdominal adhesions under laparoscopy. Open surgery was then used to remove the extra hernia sac to extensively separate tissues along the interstitial muscle line, place the patch in the abdominal cavity, suture and close the hernia ring, and close the incision. The patch was then fixed under laparoscopy. Pneumoperitoneum (12–14 mmHg pressure) was established in hybrid procedures. The laparoscope was introduced to explore the abdominal cavity, separate adhesions, and reduce the hernia content. The hernia defect was dissected 5 cm beyond the exterior margin of the inner defect (Figure 1A). Conversion to laparotomy was performed if the hernia contents could not be completely reduced. The pneumoperitoneum was evacuated with the trocars retained. A targeted fusiform incision (usually 4–8 cm long and 1–3 cm wide) was made at the weakest point of the hernia sac along the original incision line (Figure 1B). The hernia sac was completely resected by stripping, and the intestines were explored. The posterior component separation technique with transversus abdominis release was used to close the abdominal wall defect with low or no tension[17,18]. The hernia defect was closed by continuous suture using PDS-II at 1 cm intervals after the Composix E/X mesh was implanted in the abdominal cavity.

The anti-adhesive surface of the mesh was placed facing the abdominal cavity. The center of the mesh patch and the hernia ring was sutured using PDS-II sutures, and laparoscopic tacks fixed the surrounding mesh. The basic principle was that the distance between the tacks was not < 3 cm. A low-pressure (8–10 mmHg) pneumoperitoneum was reestablished, and the mesh was laparoscopically fixed with spiral tacks (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, United States; Figure 1C) using double-loop multipoint fixation at 1.5–2.0 cm intervals. The pneumoperitoneum was evacuated, and the trocars removed. Superficial tissues were closed with a 2-0 absorbable interrupted suture. The skin was closed with staples or a continuous 4-0 absorbable suture (Figure 1D).

Intraoperative serosal injuries in all cases were repaired with 3-0 absorbable sutures. Full-thickness injuries were repaired by resection, and drains were placed in the abdominal cavity if a large dissection was performed in all three procedures. Drains were placed in the pelvic cavity via the paracolic sulcus to be at the lowest position. Similarly, suction drains were subcutaneously placed. All drains were typically removed 2–3 d after the procedure. Postoperative care was the same for all three groups. All cases were advised to take necessary measures to protect the repair, including an abdominal bandage for 6 mo after the procedure and control of body weight to minimize abdominal pressure. After consulting the allergy history, patients were treated with second-generation cephalosporins. Quinolones were used if patients were allergic to cephalosporins.

The hernia recurrence rate was calculated. Intraoperative and postoperative complications, surgical time, blood loss, length of hospital stay, and mortality were also recorded. Intraoperative and postoperative complications included intraoperative intestinal injury, postoperative intestinal fistula formation, chronic pain, postoperative infection, hematoma or seroma, and perioperative mortality. Patients were followed at 1, 3, and 6 mo after the procedure and then yearly by outpatient visit or telephone interview with the surgeon. Hernia recurrence was diagnosed via physical examination and abdominal CT scan. A CT scan was requested to determine if a hernia recurrence existed if a patient described a bulge or pain in the area of the operation. Diagnosis of all recurrent hernias was based on CT and/or abdominal examination.

Chronic pain was defined as moderate or severe pain (C4) in the mesh fixation area 3 mo after the procedure based on a visual analog scale: 0 points, no pain; 1–3 points, mild pain; 4–7 points, moderate pain; and 8–10 points, severe pain. Ultrasound examination was performed in patients with suspected hematoma or seroma (suspected fluid collection on physical examination or a complaint of pain). If fine-needle aspiration produced a minimum of 10 mL of fluid, the diagnosis was made. Wound infections were defined as the presence of swelling, increased pain and temperature at the incision site, and purulent drainage.

Systemic or intra-abdominal infections were defined as a body temperature > 38 °C for 3 consecutive days, excluding respiratory and urinary tract infections and a white blood cell count > 10000 with a neutrophil ratio > 80%.

Data were expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Normally distributed data were compared using a one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni test. Moreover, categorical variables were analyzed with the χ2 test. A statistically significant difference was defined as a P < 0.05. SPSS version 20 (SPSS Statistics, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was used for all statistical analyses.

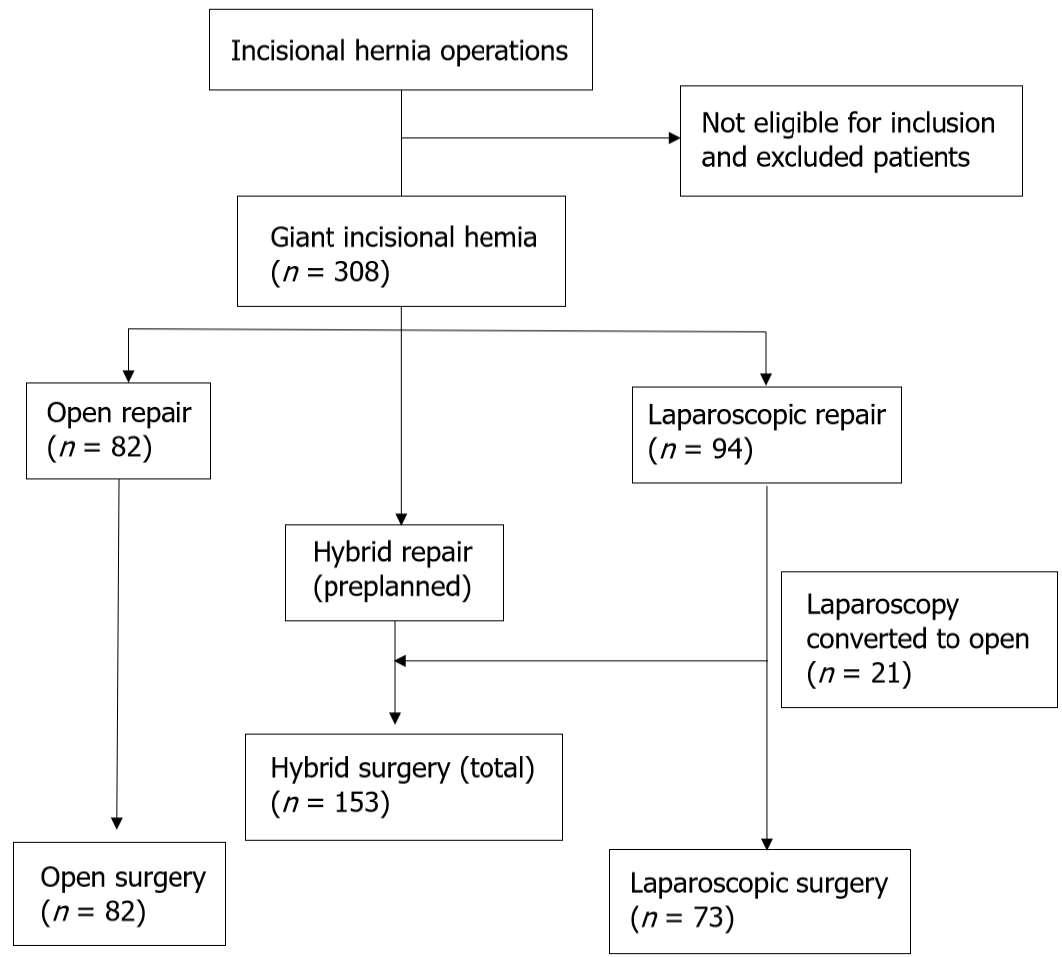

A total of 754 patients received surgical treatment for incisional hernias, and 308 cases were included. A flow diagram of patient inclusion is shown in Figure 2. Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics. The minimum and maximum hernia diameters were 10 and 30 cm, respectively. An open procedure, laparoscopic approach, and hybrid approach were performed in 82, 94, and 132 patients, respectively. Moreover, 58.7% of the patients were women, and the mean diameter of hernias was 13.11 ± 3.4 cm (range, 10–30 cm). Patients had a mean body mass index of 29.7 ± 44.6 kg/m2 (range, 16.7–38.3 kg/m2), and the three groups were comparable in demographic and baseline characteristics (all, P > 0.05).

| Open procedure (n = 82) | Laparoscopic procedure (n = 73) | Hybrid procedure (n = 153) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 63.2 ± 16.2 | 60.8 ± 15.8 | 62.6 ± 15.5 | 0.608 |

| Male sex | 33 (40.2) | 27 (37.0) | 56 (36.6) | 0.852 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.4 ± 5.3 | 29.5 ± 5.0 | 30.9 ± 4.8 | 0.054 |

| Maximum hernia diameter (cm) | 13.2 ± 3.6 | 12.7 ± 3.1 | 13.4 ± 3.4 | 0.370 |

| Cerebral or cardiovascular disease | 24 (29.2) | 18 (24.7) | 41 (26.8) | 0.810 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (26.8) | 20 (27.4) | 43 (28.1) | 0.978 |

| Other diseases related to increased IAP | 23 (28. 0) | 19 (26.0) | 34 (22.2) | 0.586 |

| Chronic cough | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0.240 |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 5 | 4 | 10 | 0.953 |

| Chronic constipation | 10 | 8 | 16 | 0.921 |

| Preoperative VAS pain score | 0.41 ± 0.89 | 0.51 ± 0.75 | 0.62 ± 0.92 | 0.212 |

The surgical details of the three groups are summarized in Table 2. The mean operation times were 76.7 ± 23.7, 63.6 ± 12.1, and 113.6 ± 21.8 min for the hybrid groups, respectively (P < 0.001). Overall, the incidence of postoperative complications was significantly lower in the hybrid group (7.23%) than in the open (17.1%; P = 0.019) or laparoscopic (26.0%; P < 0.05) groups. The intraoperative intestinal injury rates were 6.1%, 4.1%, and 1.5% in the open, laparoscopic, and hybrid groups, respectively (hybrid vs open and laparoscopic procedures; P < 0.05). In addition, the postoperative intestinal fistula formation rates in the open, laparoscopic, and hybrid groups were 2.4%, 6.8%, and 3.3%, respectively, and these differences were not significant (P > 0.05). The postoperative intestinal fistula ratio vs intraoperative intestinal injury was markedly lower in the hybrid group than in the laparoscopic group (hybrid group, 0.2; laparoscopic group, 0.7; P = 0.013) but was not different from the open group (0.4; P > 0.05). The reoperation rate was lowest in the hybrid group (3.9%; open group, 12.2%; laparoscopic group, 24.78%; P < 0.001) because it had the lowest postoperative hernia recurrence. The patients with seroma were asymptomatic. The laparoscopic procedure group had the highest seroma formation rate (32.8%; open group, 6.1%; and hybrid group, 2.6%; P < 0.001) but the lowest incidence of operative site infections (1.4%; open group, 0.3%; and hybrid group, 5.2%; P > 0.05). Patients who received an open procedure had a longer hospital stay (13.0 ± 8.7 d) than those who received laparoscopic (6.9 ± 14.2 d) and hybrid (8.5 ± 7.9 d) procedures (P = 0.002).

| Open procedure (n = 82) | Laparoscopic procedure (n = 73) | Hybrid procedure (n = 153) | P value | |

| Recurrence | 7 (8.5) | 15 (20.5) | 2 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| Re-operated patients | 10 (12.2) | 18 (24.7) | 6 (3.9) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery duration (min) | 76.7 ± 23.7 | 63.6 ± 12.1 | 113.6 ± 21.8 | < 0.001 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 28.4 ± 9.6 | 6.2 ± 3.5 | 20.9 ± 10.9 | < 0.001 |

| Length of hospitalization (d) | 13.0 ± 8.7 | 6.9 ± 16.0 | 8.9 ± 9.4 | 0.002 |

| Hospitalization cost, RMB1 | 33278 ± 18387 | 45892 ± 29887 | 43041 ± 17210 | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative intestinal injury | 5 (6.1) | 3 (4.1) | 23 (1.5) | 0.015 |

| Postoperative intestinal fistula | 2 (2.4) | 5 (6.8) | 5 (3.3) | 0.312 |

| Postoperative intestinal fistula/intraoperative intestinal injury | 0.4 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.046 |

| Seroma | 5 (6.1) | 24 (32.8) | 4 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Surgical site infection | 6 (7.3) | 1 (1.4) | 8 (5.2) | 0.220 |

| Chronic pain | 6 (7.3) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (2.0) | 0.051 |

| Perioperative mortality | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 0.735 |

| Postoperative complications | 14 (17.1) | 44 (60.3) | 11 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| 1 complication | 5 (6.1) | 40 (54.8) | 2 (1.3) | |

| 2 complications | 4 (4.9) | 4 (5.5) | 5 (3.3) | |

| 3 complications | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.0) | |

| 4 complications | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

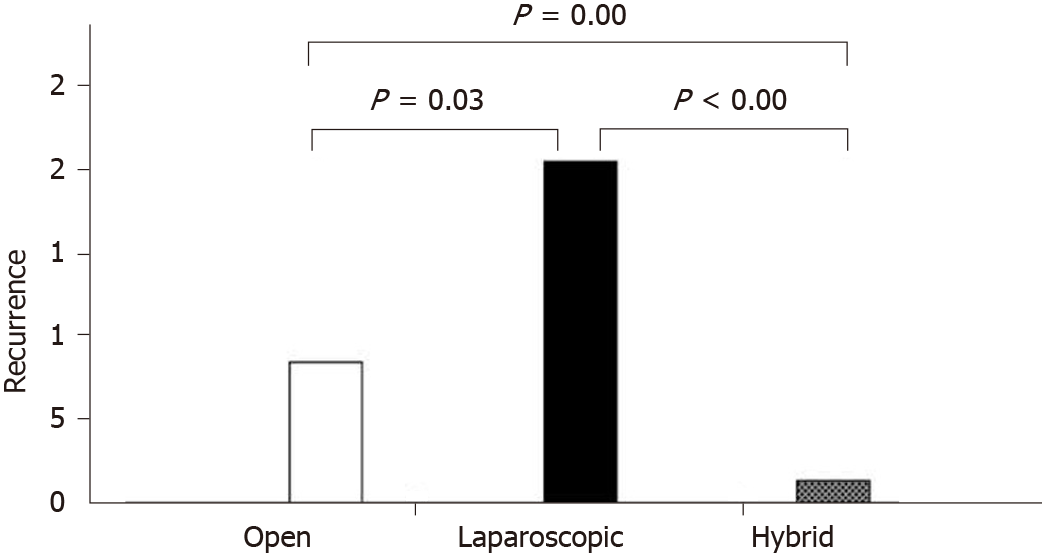

All patients were followed up 1 wk after the operation. The outpatient clinic follow-up rates at 1 mo, 3 mo, and 1 year were 40.6%, 37.3%, and 14.6%, respectively. Other patients were followed via telephone interview. The mean follow-up times for the open, laparoscopic, and hybrid groups were 45, 40, and 39 mo, respectively. Thus, the mean follow-up time for the three groups was 41 mo (range, 12–88). The follow-up time in the hybrid group was shorter than in the other two groups. The hernia recurrence rate in patients who received a hybrid procedure was 1.3% at the final follow-up. This finding was significantly lower than that in the laparoscopic (12.3%) or open groups (8.5%; P < 0.05; Figure 3).

Patients who received an open procedure had the highest rate of chronic pain (vs laparoscopic group, 1.4%; open group, 7.3%; and hybrid group, 2.0%; P > 0.05) but the lowest hospitalization costs (P < 0.001). Perioperative mortality was comparable among the three groups (open, 3.7%; laparoscopic, 2.7%; and hybrid, 2.0%; P > 0.05).

Although component separation with retromuscular mesh repair is the primary procedure used, multiple alternative strategies have been gradually investigated to overcome the high rate of hernia recurrence and the unacceptably high incidence of wound complications[19]. A hybrid procedure combining open repair with a laparoscopic technique has been increasingly reported[15,16]. However, there is no literature regarding its efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness compared to open and laparoscopic procedures. This study evaluated the outcomes and surgical complications of the hybrid approach of open and laparoscopic approaches. Hernia recurrence and complication rates were significantly lower in patients who received a hybrid procedure compared with the single application of open or laparoscopic procedures.

In a study conducted from 2006 to 2008, Ozturk et al[20] randomized 28 patients with giant incisional hernias to receive standard laparoscopic repair or a hybrid approach, i.e., laparoscopy combined with an open approach[20]. The mean length of hospital stay and the operative site infection rate were comparable in both groups. Six patients developed seromas in the laparoscopy group and one in the hybrid group. However, there were no recurrences in the hybrid group and one in the laparoscopic group. However, this study was partially compromised by the small number of cases and a short follow-up. Large hernia size, infection, and operative technique are important determinants of surgical outcomes after giant hernia repair[6,21]. This study showed that the hernia recurrence rate of the hybrid procedure was 1.3%. This finding significantly lower than a laparoscopic or open procedure and the reported recurrence rates[19]. The low recurrence rate with the hybrid technique may be due to the complete removal of the hernia sac, proper closure of the hernia defect, and satisfactory reshaping of the abdominal wall in the open phase. Careful laparoscopic exploration, adhesiolysis, mesh flattening and fixation, ensuring the integrity of abdominal wall remodeling, and avoiding hidden hernia omission also likely contribute to the low incidence of hernia recurrence[16,19].

A recent meta-analysis showed 2.7% and 8.2% recurrence in mesh and repairs, respectively[22]. The hernia recurrence rates of open and laparoscopic procedures were higher in this study, which may be due to a longer follow-up. Fink et al[2]. reported that the hernia recurrence rate with open repair increased over time (22.4% at 3 years vs 12.6% at 1 year after the procedure)[2]. Another study showed that the hernia recurrence rate increases up to 10 years after the primary incisional hernia repair[23]. Reportedly, 85% and 77% of recurrences after laparoscopic and open repair, respectively, occur within 2 years of the procedure in ventral hernias cases[24]. Therefore, a long-term follow-up is needed to determine if the hybrid approach is superior to other approaches concerning recurrence.

Patients who received a preplanned hybrid procedure had a low complication rate, indicating that careful preoperative planning and preparation are important for improving the procedure’s safety. Furthermore, a hybrid procedure was associated with a low rate of postoperative intestinal fistula formation. These results may be due to the avoidance of forced intestinal adhesiolysis, the recognition of hidden injury in the laparoscopic phase, and reliable intestinal injury repair in the open phase. Importantly, postoperative complications were significantly lower in the hybrid group. Hernia recurrence and reoperation rates were the lowest, whereas laparoscopic cases had the highest reoperation rate. This finding may be due to the preservation of the hernia sac in the laparoscopic procedure. Moreover, a laparoscopic procedure alone does not allow proper closure of the hernia defect or adequate remodeling of abdominal wall integrity, resulting in higher recurrence and seroma formation.

Patients undergoing laparoscopic or open giant ventral hernia repair have a high likelihood of chronic pain and activity limitations[25,26]. In this study, the length of hospital stay, intraoperative blood loss, and postoperative chronic pain were lowest in the hybrid group, possibly due to a smaller incision and avoidance of excessive full-thickness abdominal wall suspension fixation (transabdominal sutures), which are typically used in an open repair.

The laparoscopic group had a relatively high postoperative complication rate. Laparoscopic extraperitoneal hernia repair began in 2009, and a learning curve was evident. The definition of intestinal injury during laparoscopic manipulation was partial or full-thickness intestinal wall injury when laparoscopic hernia repair began. This complication was relatively common at the beginning of the learning curve. With advances in equipment and our experience, the current injury rate is very low. In addition, the cost of open cases was lower than for laparoscopic cases due to the cost of equipment required for laparoscopic repair. For example, using a hernia fixer (Medtronic, Shanghai, China; a product similar to ProTack) in laparoscopic repair raises the costs compared to an open procedure.

This study had some limitations. First, the retrospective nature of this study may cause biases. Second, the hernia sac volume was not examined. Moreover, the diagnosis of hernia recurrence may slightly affect lead-time bias. Last, the definition of hematoma/seroma formation may underestimate their occurrence.

In conclusion, a hybrid approach of laparoscopic and open procedures is effective for giant ventral hernia repair. It is associated with low complication and hernia recurrence rates. Hybrid repair combines laparoscopic and open repair advantages and minimizes the disadvantages of the two approaches.

Incisional hernia is a common complication of abdominal surgery. The traditional method, including open or laparoscopic surgery, still has many limitations.

This study motivated us to investigate the potential advantages of a hybrid application of open and laparoscopic approaches in giant ventral hernia repair.

This study tried to determine if a hybrid application of open and laparoscopic approaches is more effective and safer in the repair of giant ventral hernias than a single open or laparoscopic procedure.

Patients were retrospectively reviewed and divided into open (n = 82), laparoscopic (n = 73), and hybrid group (n = 153), respectively. The hernia recurrence rate, intraoperative and postoperative complications, operative time, blood loss, length of hospital stay, and mortality in the three groups were also recorded and analyzed.

Patients in the three groups were comparable in demographic and baseline characteristics (all, P > 0.05). The mean operation times of the hybrid group were significantly longer than the open and laparoscopic groups (76.7 ± 23.7 vs 63.6 ± 12.1 and 113.6 ± 21.8, P < 0.001). However, the incidence of postoperative complications was significantly lower in the hybrid group (7.23%) than in the open (17.1%; P = 0.019) or laparoscopic (26.0%; P < 0.05) groups. Besides, the hybrid group had a significantly lower intraoperative intestinal injury rate, reoperation rate, and seroma formation than the open and laparoscopic groups (1.5% vs 6.1% and 4.1%, P < 0.05; 3.9% vs 12.2% and 24.78%, P < 0.001; 2.6% vs 6.1% and 32.8%, P < 0.001).

The hybrid approach of laparoscopic and open procedures is associated with lower complication and hernia recurrence rates. It combines the advantages of laparoscopic and open repair and minimizes the disadvantages of the two approaches.

The hybrid approach of the laparoscopic and open procedures, which is worthy of clinical application, is an effective method for giant ventral hernia repair.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kim WR, Mishra TS S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Le Huu Nho R, Mege D, Ouaïssi M, Sielezneff I, Sastre B. Incidence and prevention of ventral incisional hernia. J Visc Surg. 2012;149:e3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fink C, Baumann P, Wente MN, Knebel P, Bruckner T, Ulrich A, Werner J, Büchler MW, Diener MK. Incisional hernia rate 3 years after midline laparotomy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:51-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Muysoms FE, Miserez M, Berrevoet F, Campanelli G, Champault GG, Chelala E, Dietz UA, Eker HH, El Nakadi I, Hauters P, Hidalgo Pascual M, Hoeferlin A, Klinge U, Montgomery A, Simmermacher RK, Simons MP, Smietański M, Sommeling C, Tollens T, Vierendeels T, Kingsnorth A. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13:407-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Surgical treatment for abdominal incisional hernia: protocol for a systematic review. Chin J Gen Surg. 2004;19:125. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rogmark P, Petersson U, Bringman S, Eklund A, Ezra E, Sevonius D, Smedberg S, Osterberg J, Montgomery A. Short-term outcomes for open and laparoscopic midline incisional hernia repair: a randomized multicenter controlled trial: the ProLOVE (prospective randomized trial on open vs laparoscopic operation of ventral eventrations) trial. Ann Surg. 2013;258:37-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Carter SA, Hicks SC, Brahmbhatt R, Liang MK. Recurrence and pseudorecurrence after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: predictors and patient-focused outcomes. Am Surg. 2014;80:138-148. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ahonen-Siirtola M, Nevala T, Vironen J, Kössi J, Pinta T, Niemeläinen S, Keränen U, Ward J, Vento P, Karvonen J, Ohtonen P, Mäkelä J, Rautio T. Laparoscopic versus hybrid approach for treatment of incisional ventral hernia: a prospective randomised multicentre study, 1-year results. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:88-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sriussadaporn S, Pak-Art R, Bunjongsat S. Immediate closure of the open abdomen with bilateral bipedicle anterior abdominal skin flaps and subsequent retrorectus prosthetic mesh repair of the late giant ventral hernias. J Trauma. 2003;54:1083-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Picazo-Yeste J, Morandeira-Rivas A, Moreno-Sanz C. Multilayer myofascial-mesh repair for giant midline incisional hernias: a novel advantageous combination of old and new techniques. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1665-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cobb WS, Warren JA, Ewing JA, Burnikel A, Merchant M, Carbonell AM. Open retromuscular mesh repair of complex incisional hernia: predictors of wound events and recurrence. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lowe JB, Garza JR, Bowman JL, Rohrich RJ, Strodel WE. Endoscopically assisted "components separation" for closure of abdominal wall defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:720-9; quiz 730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sharma A, Mehrotra M, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M, Chowbey PK. Limited-conversion technique: a safe and viable alternative to conversion in laparoscopic ventral/incisional hernia repair. Hernia. 2008;12:367-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zachariah SK, Kolathur NM, Balakrishnan M, Parakkadath AJ. Minimal incision scar-less open umbilical hernia repair in adults - technical aspects and short-term results. Front Surg. 2014;1:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Yoshikawa K, Shimada M, Kurita N, Sato H, Iwata T, Higashijima J, Chikakiyo M, Nishi M, Kashihara H, Takasu C, Matsumoto N, Eto S. Hybrid technique for laparoscopic incisional ventral hernia repair combining laparoscopic primary closure and mesh repair. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2014;7:282-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Griniatsos J, Yiannakopoulou E, Tsechpenakis A, Tsigris C, Diamantis T. A hybrid technique for recurrent incisional hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:e177-e180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stoikes N, Quasebarth M, Brunt LM. Hybrid ventral hernia repair: technique and results. Hernia. 2013;17:627-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pauli EM, Rosen MJ. Open ventral hernia repair with component separation. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:1111-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fox M, Cannon RM, Egger M, Spate K, Kehdy FJ. Laparoscopic component separation reduces postoperative wound complications but does not alter recurrence rates in complex hernia repairs. Am J Surg. 2013;206:869-74; discussion 874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bikhchandani J, Fitzgibbons RJ Jr. Repair of giant ventral hernias. Adv Surg. 2013;47:1-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ozturk G, Malya FU, Ersavas C, Ozdenkaya Y, Bektasoglu H, Cipe G, Citgez B, Karatepe O. A novel reconstruction method for giant incisional hernia: Hybrid laparoscopic technique. J Minim Access Surg. 2015;11:267-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ballem N, Parikh R, Berber E, Siperstein A. Laparoscopic vs open ventral hernia repairs: 5 year recurrence rates. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1935-1940. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nguyen MT, Berger RL, Hicks SC, Davila JA, Li LT, Kao LS, Liang MK. Comparison of outcomes of synthetic mesh vs suture repair of elective primary ventral herniorrhaphy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:415-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 23. | Burger JW, Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, Halm JA, Verdaasdonk EG, Jeekel J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture vs mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg. 2004;240:578-583. |

| 24. | Singhal V, Szeto P, VanderMeer TJ, Cagir B. Ventral hernia repair: outcomes change with long-term follow-up. JSLS. 2012;16:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wassenaar EB, Raymakers JT, Rakic S. Removal of transabdominal sutures for chronic pain after laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:514-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wormer BA, Walters AL, Bradley JF 3rd, Williams KB, Tsirline VB, Augenstein VA, Heniford BT. Does ventral hernia defect length, width, or area predict postoperative quality of life? J Surg Res. 2013;184:169-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |