Published online Jan 7, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.323

Peer-review started: June 21, 2021

First decision: July 14, 2021

Revised: July 29, 2021

Accepted: November 29, 2021

Article in press: November 29, 2021

Published online: January 7, 2022

Processing time: 192 Days and 4.7 Hours

The incidence of internal hernias has recently increased in concordance with the popularization of laparoscopic surgery. Of particular concern are internal hernias occurring in Petersen's space, a space that is surgically created after treatment for gastric cancer and obesity. These hernias cause devastating sequelae, such as massive intestinal necrosis, fatal Roux limb necrosis, and superior mesenteric vein thrombus. In addition, protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a rare syndrome involving gastrointestinal protein loss, although its relationship with internal Petersen’s hernias remains unknown.

A 75-year-old man with a history of laparotomy for early gastric cancer developed Petersen's hernia 1 year and 5 mo after surgery. He was successfully treated by reducing the incarcerated small intestine and closure of Petersen’s defect without resection of the small intestine. Approximately 3 mo after his surgery for Petersen’s hernia, he developed bilateral leg edema and hypoalbuminemia. He was diagnosed with PLE with an alpha-1 antitrypsin clearance of 733 mL/24 h. Double-balloon enteroscopy revealed extensive jejunal ulceration as the etiology, and it facilitated minimum bowel resection. Pathological analysis showed extensive jejunal ulceration and collagen hyperplasia with nonspecific inflammation of all layers without lymphangiectasia, lymphoma, or vascular abnor

PLE and extensive jejunal ulceration may occur after Petersen's hernia. Double-balloon enteroscopy helps identify and resect these lesions.

Core Tip: The incidence of internal hernias has recently increased in concordance with the increasing popularity of laparoscopic surgery. Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a rare syndrome involving gastrointestinal protein loss. However, its relationship with internal Petersen’s hernias remains unknown. This report presents a rare case of PLE caused by a jejunum segmental ulcer following an internal hernia in Petersen’s space. PLE and extensive jejunal ulceration may follow the reduction of Petersen's hernia. Double-balloon enteroscopy revealed the etiology of PLE and enabled minimal bowel resection in this case.

- Citation: Yasuda T, Sakurazawa N, Kuge K, Omori J, Arai H, Kakinuma D, Watanabe M, Suzuki H, Iwakiri K, Yoshida H. Protein-losing enteropathy caused by a jejunal ulcer after an internal hernia in Petersen's space: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(1): 323-330

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i1/323.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.323

Internal hernias are the center of attention again as their incidence has increased worldwide with the popularization of laparoscopic surgery in what is considered a global gastrointestinal emergency[1-3]. Internal hernias were originally defined by Steinke[4] in 1932 as a state of intestinal intrusion or protrusion into an unusual fossa, fovea, or foramen in the abdominal cavity and are often found in strangulated bowel obstruction as well as after surgery for gastric cancer and obesity in Petersen’s space. This surgically created space is surrounded by the transverse colon and jejunal mesentery. Internal hernias in this space are a fairly common postoperative compli

Here we report the case of a patient who presented with bilateral leg edema and hypoalbuminemia 4 mo after developing an internal hernia in Petersen’s space. The etiology of this PLE was found to be a wide area of jejunal ulceration with stenosis, with the diagnosis confirmed through double-balloon endoscopy (DBE). DBE faci

Following an open gastrectomy for early-stage gastric cancer and a subsequent internal hernia in Petersen’s space, reduction of this internal hernia, and incident bilateral leg edema, a 75-year-old man presented at the emergency room of our medical center with a recurrence of post-surgical bilateral leg edema.

A 75-year-old man with a history of diabetes and hypertension had undergone an open gastrectomy for early-stage gastric cancer 1 year and 5 mo before the occurrence of an internal hernia in Petersen’s space. Following the initial surgery, he was treated conservatively on an outpatient basis without receiving chemotherapy and showed no recurrence or metastasis. At this point (1 year and 5 mo after the gastric cancer surgery), he presented at the emergency room of our medical center with complaints of mild, occasional abdominal distention and pain after meals that had mainly resolved naturally and a worrisome continued loss of appetite over approximately the past two weeks. Following imaging examinations described below, an internal hernia in Petersen's space was suspected, and laparoscopy was immediately performed. The operation revealed small intestine intrusion in Petersen's space, which was challenging to reduce laparoscopically. The patient underwent laparotomy, and the incarcerated small intestine was restored successfully, and the Petersen's defect was sutured using a non-absorbable thread. There was no necrosis of the intestine, and bowel resection was not performed. After surgery, the patient was managed with analgesia (mainly epidural anesthesia). He was administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as flurbiprofen axetil (twice on the day of surgery and the next day) during his hospitalization and later follow-up. Excluding a mild surgical site infection, the patient had a good postoperative course and was discharged on the fifteenth day after surgery.

Approximately 3 mo after his surgery for Petersen’s hernia, the patient developed bilateral leg edema, with laboratory findings and diagnostic imaging scans described in detail below. Briefly, as a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed no thrombus in the SMV but a slight thrombus in the lower limb, the patient was started on oral edoxaban. Although the etiology of this complication was not discerned, prompt recovery of his leg edema after administration of albumin solutions and diuretics resulted in early discharge. However, the leg edema resurfaced three weeks after discharge, and the patient was re-admitted for examination.

The patient had a history of Type II diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Apart from this, his medical history was uncomplicated before early-stage gastric cancer, with no chronic or acute major illnesses, infections, or injuries.

The patient’s height was 157 cm, and his weight was 51 kg. He was retired and did not have any family history of cancer or allergies to food and drugs. His medical history included Type II diabetes mellitus and hypertension, both of which were well controlled without oral treatment and insulin injection or any diet at the time of pre

Blood test results, including those for renal and hepatic function, at the time of admission were as follows: Total protein, 4.2 g/dL; albumin, 1.9 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 33.1 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.83 mg/dL; Na, 136 mEq/L; K, 4.4 mEq/L; Cl, 100 mEq/L; Ca, 7.1 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 45 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 33 U/L; total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL; direct bilirubin, 0.2 mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase, 336 U/L; creatine phosphokinase, 116 U/L; amylase, 51 U/L; cholinesterase, 70 U/L; total cholesterol, 131 mg/dL; high density lipoprotein cholesterol, 51 mg/dL; low density lipoprotein cholesterol, 63 mg/dL; and triglyceride, 88 mg/dL.

He followed an ordinary diet before admission and switched to a low-fat, high-protein, elemental diet in the hospital.

During the patient’s second incidence of bilateral leg edema, we performed technetium diethyl-enetriamine-pentaacetic acid human serum albumin lymphoscintigraphy, which showed accumulation in the ascending and transverse colon. However, no abnormalities were found on colonoscopy. Capsule endoscopy was performed to examine the small intestine, revealing an extensive jejunal ulcer with stenosis. The capsule was stalled by this stenosis. Oral DBE was performed to retrieve the capsule and closely examine the lesions in the jejunum, revealing continuous jejunal ulceration with circumferential stenosis and erosion extending approximately 8 cm. Tissue biopsy was performed to differentiate lymphoma and small intestine cancer, and India ink injection was used to mark the lesion via DBE. Transanal DBE could not reach the jejunal ulcer and stenosis. No other lesions were found in the intestine.

As previously described, approximately 3 mo following this patient’s surgery for Petersen’s hernia, he developed bilateral leg edema. Four months after the surgery, his serum albumin had dropped to 1.9 g/dL, and his total serum protein levels had dropped to 4.2 g/dL, resulting in admission to the hospital for additional examination. At the first incidence of leg edema, blood tests showed no liver dysfunction, and urine tests for protein were negative. In addition, no signs of lymphoma or small intestine cancer were detected by histopathology during diagnostic tests performed following the second incidence of leg edema.

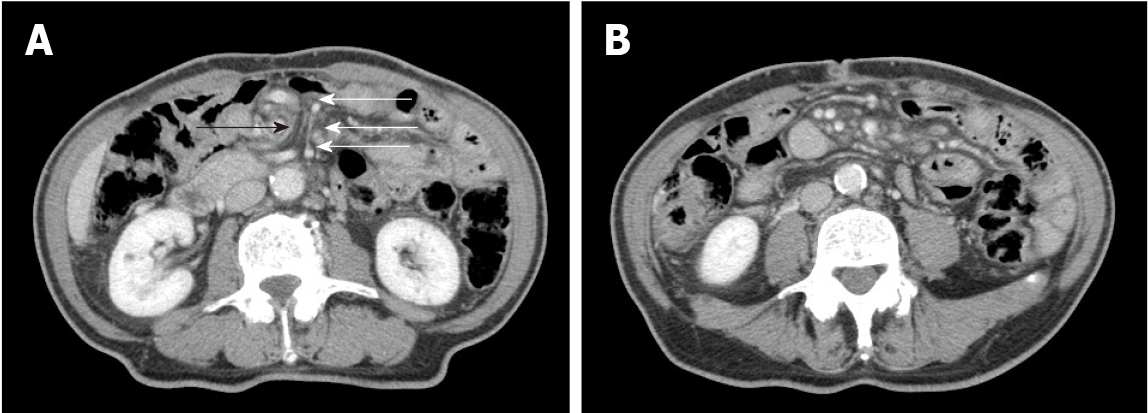

Upon the patient’s presentation with Petersen’s hernia, a contrast-enhanced CT scan showed an SMV twisted around the superior mesenteric artery in a spiral-like pattern, as well as venous congestion in the small intestine mesentery (Figure 1). On presen

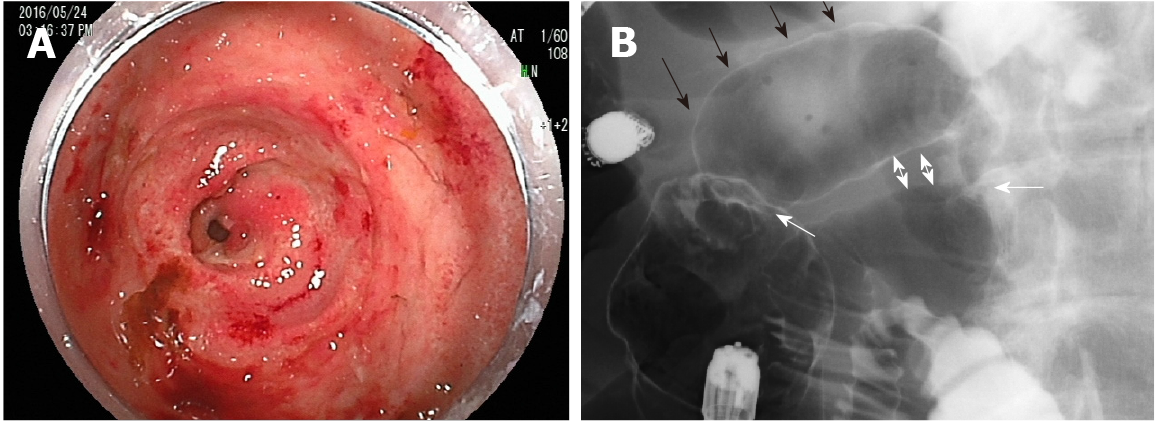

As this patient had no signs of inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., diarrhea or similar gastrointestinal symptoms), based on the previously described physical examinations, procedures, laboratory findings, and imaging scans, he was diagnosed with PLE with an alpha-1 antitrypsin clearance of 733 mL/24 h. Oral DBE revealed an extensive and continuous jejunal ulcer with circumferential stenosis and erosion extending approximately 8 cm; amidotrizoic acid radiography revealed that this stenosis and poor dilation extended approximately 6 cm (Figure 2). No signs of lymphoma or small intestine cancer were detected, and PLE was diagnosed as an extensive jejunal ulcer with stenosis, occurring as a post-surgical complication following an internal hernia in Petersen's space.

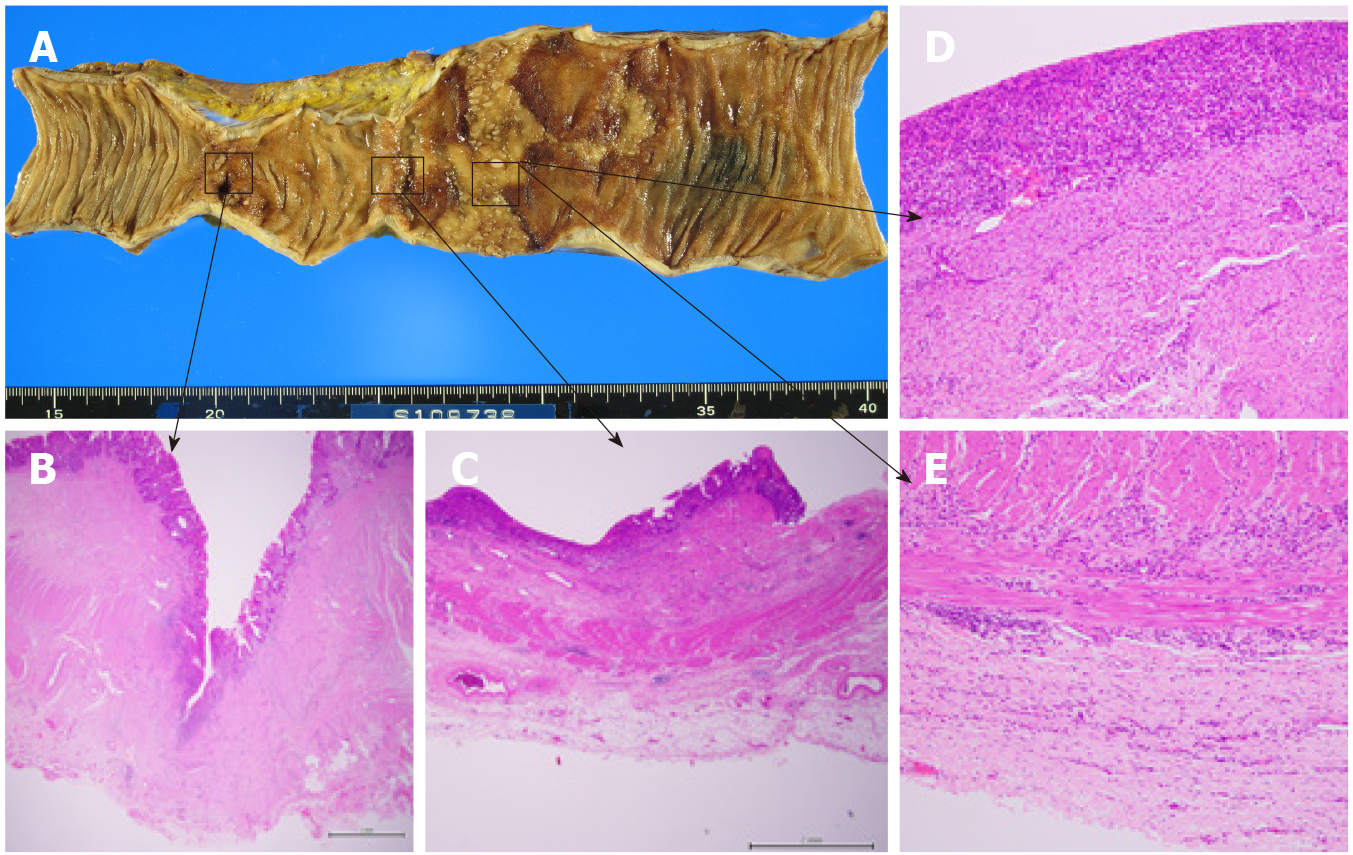

One week after the DBE, albumin solutions were administered again to treat bilateral leg edema, and laparotomy was performed. The jejunum proximal to the stenosis was extensively dilated, and marked ulcerative lesions were found. Therefore, only the jejunum between the stenosis and the marked jejunum was resected, and the remaining jejunum was anastomosed. The patient had a good postoperative course and was discharged on the 16th day following the final surgery. Pathological findings examining the ulcerative lesions showed a deep-mining ulcer in the jejunum (to the muscularis propria) with collagen hyperplasia and a shallow ulcer with extensive epithelial loss and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in all layers; pathological findings showed no evidence of lymphangiectasia, lymphoma, or vascular abnor

One month after discharge, the patient was edema-free, and his serum albumin and total protein levels had recovered to within normal limits. He has been free from leg edema and hypoalbuminemia over five years of follow-up.

This case report demonstrated two clinically important points. First, PLE complicated by extensive jejunal ulceration can develop in a delayed manner following the reduction of Petersen's hernia. Second, late-onset ulceration and stenosis of the jejunum occur in a segment of the small intestine vasculature following reduction of Petersen’s hernia, and preoperative DBE can help identify and successfully resect such lesions.

According to a recent review, PLE can be divided into erosive and non-erosive inte

Possible explanations for this mechanism include intestinal ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation and the characteristic wide Petersen’s space. It has long been shown in animal experiments that ischemia-reperfusion injury after a limited period of ischemia (i.e., the “window of reperfusion injury”) causes intense inflammation in all layers of the intestine[13,14]. It has likewise been shown that intensive inflammation due to prolonged intestinal ischemia reperfusion results in failure to restore damaged epithelium[15]. As Petersen's hernia has a wide hernial orifice and an accommodating space, intestinal necrosis is rare. However, a large amount of the small intestine is incarcerated. Therefore, extensive unrepaired epithelium caused by ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation in cases of Petersen’s hernia can lead to PLE.

The efficacy of DBE for the diagnosis of PLE as well as obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and small bowel strictures has been demonstrated previously[16-23,25]. DBE has also been reported to be useful for not only treatments such as hemostasis, polypectomy, and balloon dilation but also preoperative India ink injection[24-29]. In this case, DBE revealed extensive intestinal damage with stenosis, poor dilation of > 5 cm, and a continuous ulcer of approximately 8 cm. Although resection of this sizable segmental lesion (which was due to ischemia) required minimal bowel resection, a dilated intestine (due to stenosis) makes surgical identification of extensive ulceration difficult. DBE effectively determined the extent of the lesion in the intestinal lumen before surgery, facilitating a combination of detailed observation, amidotrizoic acid radiography, tissue biopsy, and India ink injection. Thus, it not only revealed a rare form of extensive jejunal ulceration after an internal hernia in Petersen’s space but also proved to be an effective procedure from diagnosis to successful treatment with minimal bowel resection.

Following the reduction of Petersen's hernia, PLE complicated by extensive jejunal ulceration may develop in a delayed fashion. DBE is useful for identifying and re

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research, and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arslan M S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Fan HP, Yang AD, Chang YJ, Juan CW, Wu HP. Clinical spectrum of internal hernia: a surgical emergency. Surg Today. 2008;38:899-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Martin LC, Merkle EM, Thompson WM. Review of internal hernias: radiographic and clinical findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:703-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ong AW, Myers SR. Early postoperative small bowel obstruction: A review. Am J Surg. 2020;219:535-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Steinke CR. Internal hernia: Three additional case reports. Arch Surg. 1932;25:909-925. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yoshikawa K, Shimada M, Kurita N, Sato H, Iwata T, Higashijima J, Chikakiyo M, Nishi M, Kashihara H, Takasu C, Matsumoto N, Eto S. Characteristics of internal hernia after gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1774-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kelly KJ, Allen PJ, Brennan MF, Gollub MJ, Coit DG, Strong VE. Internal hernia after gastrectomy for cancer with Roux-Y reconstruction. Surgery. 2013;154:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fabozzi M, Brachet Contul R, Millo P, Allieta R. Intestinal infarction by internal hernia in Petersen's space after laparoscopic gastric bypass. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16349-16354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:43-9; quiz 50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Keuchel M, Kurniawan N, Baltes P. Small bowel ulcers: when is it not inflammatory bowel disease? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2019;35:213-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chandra Chakinala R, Katchi T, Jolly GP, Haq KF, Solanki S, Barbash B. Ulcerative Jejunoileitis Presenting as Protein-Losing Enteropathy: A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Dilemma. Am J Ther. 2020;27:e297-e298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tainaka T, Ikegami R, Watanabe Y. Left paraduodenal hernia leading to protein-losing enteropathy in childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:E21-E23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Evans JD, Perera MT, Pal C, Neuberger J, Mirza DF. Late post liver transplant protein losing enteropathy: rare complication of incisional hernia. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4409-4412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Park PO, Haglund U, Bulkley GB, Fält K. The sequence of development of intestinal tissue injury after strangulation ischemia and reperfusion. Surgery. 1990;107:574-580. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Parks DA, Granger DN. Contributions of ischemia and reperfusion to mucosal lesion formation. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:G749-G753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Grootjans J, Lenaerts K, Derikx JP, Matthijsen RA, de Bruïne AP, van Bijnen AA, van Dam RM, Dejong CH, Buurman WA. Human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation characterized: experiences from a new translational model. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2283-2291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Takenaka H, Ohmiya N, Hirooka Y, Nakamura M, Ohno E, Miyahara R, Kawashima H, Itoh A, Watanabe O, Ando T, Goto H. Endoscopic and imaging findings in protein-losing enteropathy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:575-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kamata Y, Iwamoto M, Nara H, Kamimura T, Takayashiki N, Yamamoto H, Sugano K, Yoshio T, Okazaki H, Minota S. A case of rheumatoid arthritis with protein losing enteropathy induced by multiple diaphragmatic strictures of the small intestine: successful treatment by bougieing under double-balloon enteroscopy. Gut. 2006;55:1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pungpapong S, Stark ME, Cangemi JR. Protein-losing enteropathy from eosinophilic enteritis diagnosed by wireless capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:917-8; discussion 918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gerson LB, Fidler JL, Cave DR, Leighton JA. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1265-87; quiz 1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Otani K, Watanabe T, Shimada S, Hosomi S, Nagami Y, Tanaka F, Kamata N, Taira K, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Shiba M, Fujiwara Y. Clinical Utility of Capsule Endoscopy and Double-Balloon Enteroscopy in the Management of Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Digestion. 2018;97:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kakiya Y, Shiba M, Okamoto J, Kato K, Minamino H, Ominami M, Fukunaga S, Nagami Y, Sugimori S, Tanigawa T, Yamagami H, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. A comparison between capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy using propensity score-matching analysis in patients with previous obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:306-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kroner PT, Brahmbhatt BS, Bartel MJ, Stark ME, Lukens FJ. Yield of double-balloon enteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of small bowel strictures. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:446-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hayashi Y, Yamamoto H, Taguchi H, Sunada K, Miyata T, Yano T, Arashiro M, Sugano K. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small-bowel lesions identified by double-balloon endoscopy: endoscopic features of the lesions and endoscopic treatments for diaphragm disease. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44 Suppl 19:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nishimura N, Yamamoto H, Yano T, Hayashi Y, Sato H, Miura Y, Shinhata H, Sunada K, Sugano K. Balloon dilation when using double-balloon enteroscopy for small-bowel strictures associated with ischemic enteritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1157-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gill RS, Kaffes AJ. Small bowel stricture characterization and outcomes of dilatation by double-balloon enteroscopy: a single-centre experience. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:108-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Belsha D, Urs A, Attard T, Thomson M. Effectiveness of Double-balloon Enteroscopy-facilitated Polypectomy in Pediatric Patients With Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:500-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tang L, Huang LY, Cui J, Wu CR. Effect of Double-Balloon Enteroscopy on Diagnosis and Treatment of Small-Bowel Diseases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018;131:1321-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Urs AN, Martinelli M, Rao P, Thomson MA. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of double-balloon enteroscopy in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:204-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sato T, Kogure H, Nakai Y, Ishigaki K, Hakuta R, Saito K, Saito T, Takahara N, Hamada T, Mizuno S, Yamada A, Tada M, Isayama H, Koike K. Double-balloon endoscopy-assisted treatment of hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic strictures and predictive factors for treatment success. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:1612-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim JS, Kim HJ, Hong SM, Park SH, Lee JS, Kim AY, Ha HK. Post-Ischemic Bowel Stricture: CT Features in Eight Cases. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18:936-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |