Published online Jan 7, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.275

Peer-review started: March 23, 2021

First decision: September 1, 2021

Revised: September 9, 2021

Accepted: November 28, 2021

Article in press: November 28, 2021

Published online: January 7, 2022

Processing time: 282 Days and 4.5 Hours

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is a common gynecologic complaint among elderly women, and endometrial hyperplasia is a common cause of this bleeding. Ovarian fibromas are the most common type of ovarian sex cord-stromal tumor (SCST). They arise from non-functioning stroma, rarely show estrogenic activity, and stimulate endometrial hyperplasia, causing abnormal vaginal bleeding.

We report herein the case of a 64-year-old Chinese woman who presented with recurrent PMB. A sex hormone test revealed that her estrogen level was significantly higher than normal, and other causes of hyperestrogenism had been excluded. The patient had undergone four curettage and hysteroscopy procedures in the past 7 years due to recurrent PMB and endometrial hyperplasia. The culprit behind the increase in estrogen level—an ovarian cellular fibroma with estrogenic activity—was eventually found during the fifth operation.

Ovarian cellular fibromas occur insidiously, and some may have endocrine functions. Postmenopausal patients with recurrent PMB and endometrial thickening observed on ultrasonography are recommended to undergo sex hormone testing while waiting for results regarding the pathology of the endometrium. If the estrogen level remains elevated, the clinician should consider the possibility of an ovarian SCST and follow-up the patient closely, even if the imaging results do not indicate ovarian tumors. Once the tumor is found, it should be removed as soon as possible no matter the size to avoid endometrial lesions due to long-term estrogen stimulation. More studies are needed to confirm whether preventive total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be recommended for women with recurrent PMB exhibiting elevated estrogen levels, despite the auxiliary examination results not indicating ovarian mass. The physical and psychological burden caused by repeated curettage could be prevented using this technique.

Core Tip: This case demonstrates the necessity of considering the rare possibility of ovarian cellular fibroma as a precursor of postmenopausal bleeding.

- Citation: Wang J, Yang Q, Zhang NN, Wang DD. Recurrent postmenopausal bleeding - just endometrial disease or ovarian sex cord-stromal tumor? A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(1): 275-282

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i1/275.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.275

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is a common gynecologic complaint encountered in the clinical setting. Inflammation and benign or malignant tumors of the reproductive organs can cause PMB. The keys to diagnosis and treatment are accurately determining the etiology and preventing and treating malignant diseases. Correct identification of the etiology improves the treatment plan and facilitates early patient recovery. We report the case of a postmenopausal woman who had previously undergone repeated curettage and hysteroscopy due to recurrent PMB and endometrial hyperplasia. Sex-hormone testing revealed her estrogen levels were consistently higher than normal. However, imaging performed as part of her first four operations did not reveal an ovarian mass. An ovarian cellular fibroma with endocrine function was eventually found during the fifth operation, and the relevant literature was reviewed. This case is significant because it demonstrates the necessity of considering the rare possibility of ovarian cellular fibromas as a precursor for PMB.

A 64-year-old female patient presented in May 2020 for “postmenopausal vaginal bleeding for one year”.

The vaginal bleeding was intermittent, less than the amount of previous menstruation. The patient had no feeling of dizziness and fatigue, but was accompanied by slight abdominal pain and occasional abdominal distension.

In June 2013, 4 years after menopause, the patient began to experience irregular vaginal bleeding without obvious cause. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) showed the endometrium was thickened (approximately 1.5 cm in total), and diagnostic curettage was performed. The pathological results suggested simple endometrial hyperplasia.

In May 2014, diagnostic curettage was performed again due to irregular vaginal bleeding, and the pathological results suggested endometrial hyperplasia disorder. The first two curettage procedures were performed at a different hospital.

In June 2016, irregular vaginal bleeding occurred again. Gynecological examination showed that the cervix was normally sized, the uterus was enlarged and the shape was irregular, and there were no abnormalities in the adnexa area of either side. TVUS showed the size of the uterus was about 9.0 cm × 6.1 cm × 6.0 cm, the endometrium was thickened (approximately 1.9 cm), and the echo was uneven. Several hypoechoic masses were observed in the uterine area; the largest one was in the lower part of the anterior wall, and approximately 2.2 cm × 2.1 cm × 1.9 cm in size with a clear boundary. The size of the left ovary was 2.1 cm × 1.4 cm, and the size of the right ovary was 2.0 cm × 1.2 cm. No obvious mass was present in both adnexa. Further hysteroscopy showed that the endometrium of the posterior wall of the uterus was focally thickened, and multiple polypoid lesions were observed in the uterine cavity; the larger one was approximately 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm in size and soft and pink with a smooth surface. The cervical mucosa was smooth. The sex hormone test revealed the following: estradiol (E2), 63 pg/mL (normal range: < 20-40 pg/mL); human follicle stimulating hormone (hFSH), 29.01 mIU/mL (normal range: 16.24-113.59 mIU/mL); human luteinizing hormone (hLH), 26.54 mIU/mL (normal range: 10.87-58.64 mIU/mL); progesterone (Prog), 0.33 ng/mL (normal range: 0.01-0.78 ng/mL); and testosterone (Testo), 0.46 ng/mL (normal range: < 0.1-0.75 ng/mL). Hysteroscopic endometrial polypectomy was performed on June 27, 2016, and the pathological results revealed endometrial polyps with secretory changes. The bleeding disappeared after the operation.

The patient had experienced menopause at the age of 53; her body mass index was 18.75 kg/m2, she reported no risk factors for endometrial cancer such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, or genetic diseases; she had no history of hormonal drug use; and her adrenal glands were normal in size. She had one pregnancy and one previous delivery (G1P1). Her family history was unremarkable.

Gynecologic examination: the cervix was normal in size with a smooth surface and no cervical atrophy, the uterus was enlarged and irregular, and no abnormalities were found in bilateral adnexa.

Sex-hormone test: E2: 124 pg/mL, hFSH: 33.31 mIU/mL, hLH: 26.97 mIU/mL, Prog: 1.04 ng/mL, Testo: 1.10 ng/mL. The serum carbohydrate antigen (CA)-199, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA-125, and CA-724 levels were normal.

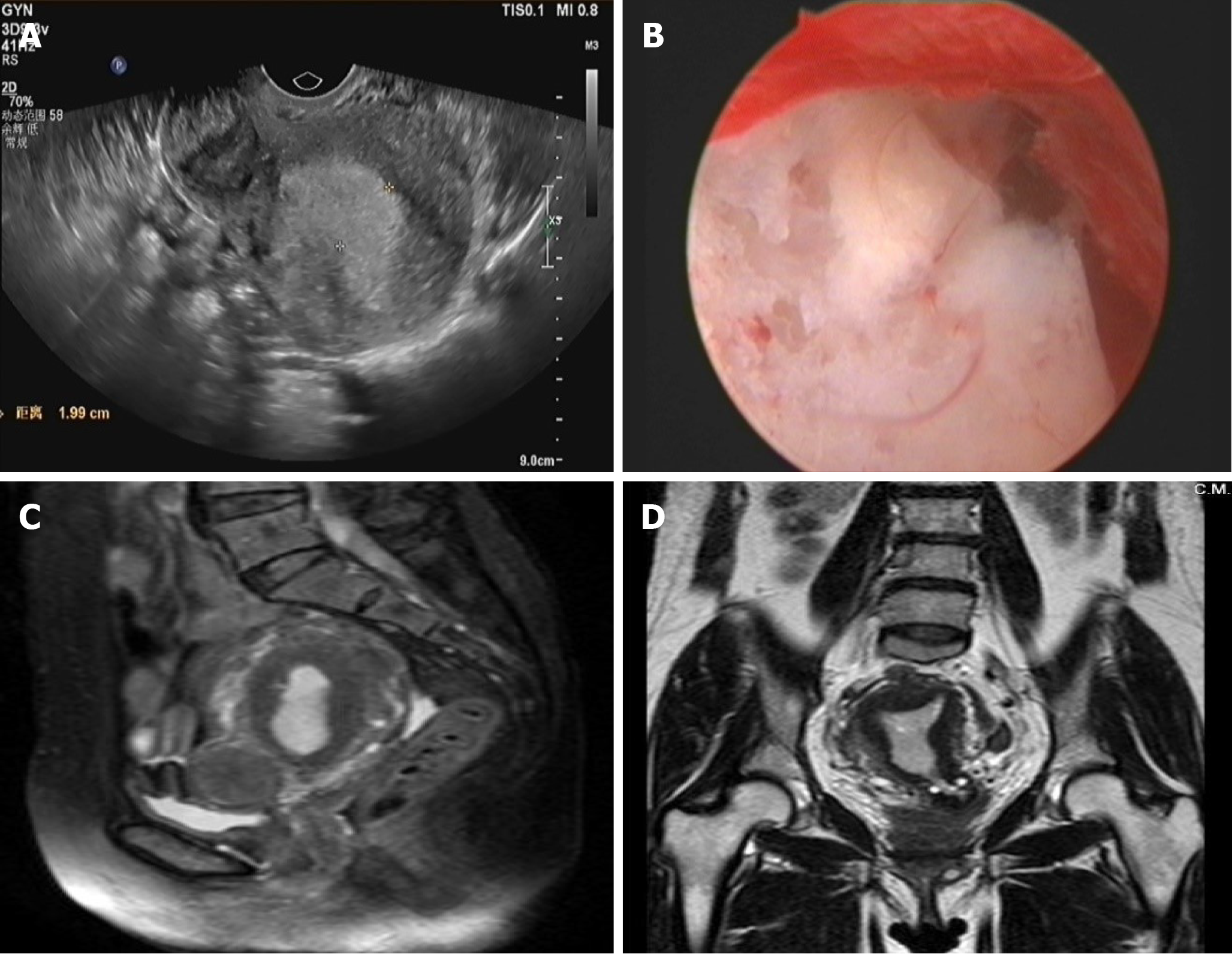

Before the fourth operation: TVUS (Figure 1A) showed the uterus to be approximately 8.2 cm × 6.3 cm × 5.7 cm in size, and the endometrium was approximately 2.0-cm thick. Several hypoechoic masses were observed in the uterine area. The largest one (3.6 cm × 3.4 cm × 2.7 cm) was located in the isthmus of the anterior wall and had a clear boundary. The size of the left ovary was 2.1 cm × 1.7 cm × 1.0 cm, and the size of the right ovary was 1.9 cm × 1.3 cm × 1.2 cm. There was no obvious mass in bilateral adnexa. Hysteroscopy (Figure 1B) revealed that the endometrium was extensively thickened, and the cervical mucosa was smooth. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (Figures 1C, D) showed the uterus was enlarged, the endometrium was thickened (approximately 1.6 cm in total), and the signal in the right corner of the uterine cavity was not uniform.

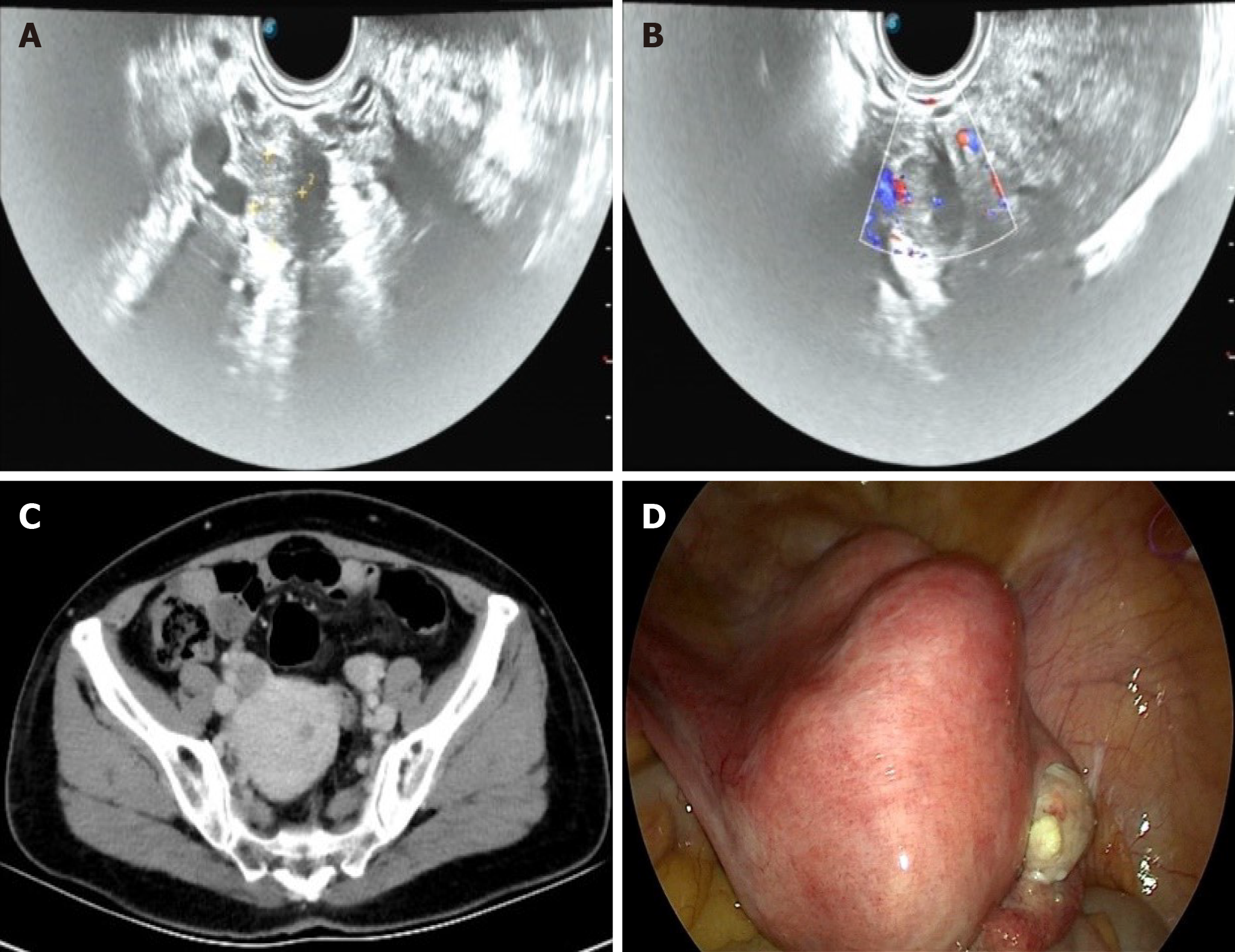

Before the fifth operation: TVUS (Figure 2A and B) showed the endometrium was approximately 0.6 cm thick, and there were several hypoechoic masses in the uterine area. The right ovary was approximately 2.2 cm × 1.7 cm × 1.5 cm in size, with a 1.6 cm × 1.2 cm × 1.2 cm mass being observed inside. It had clear borders and was hypo

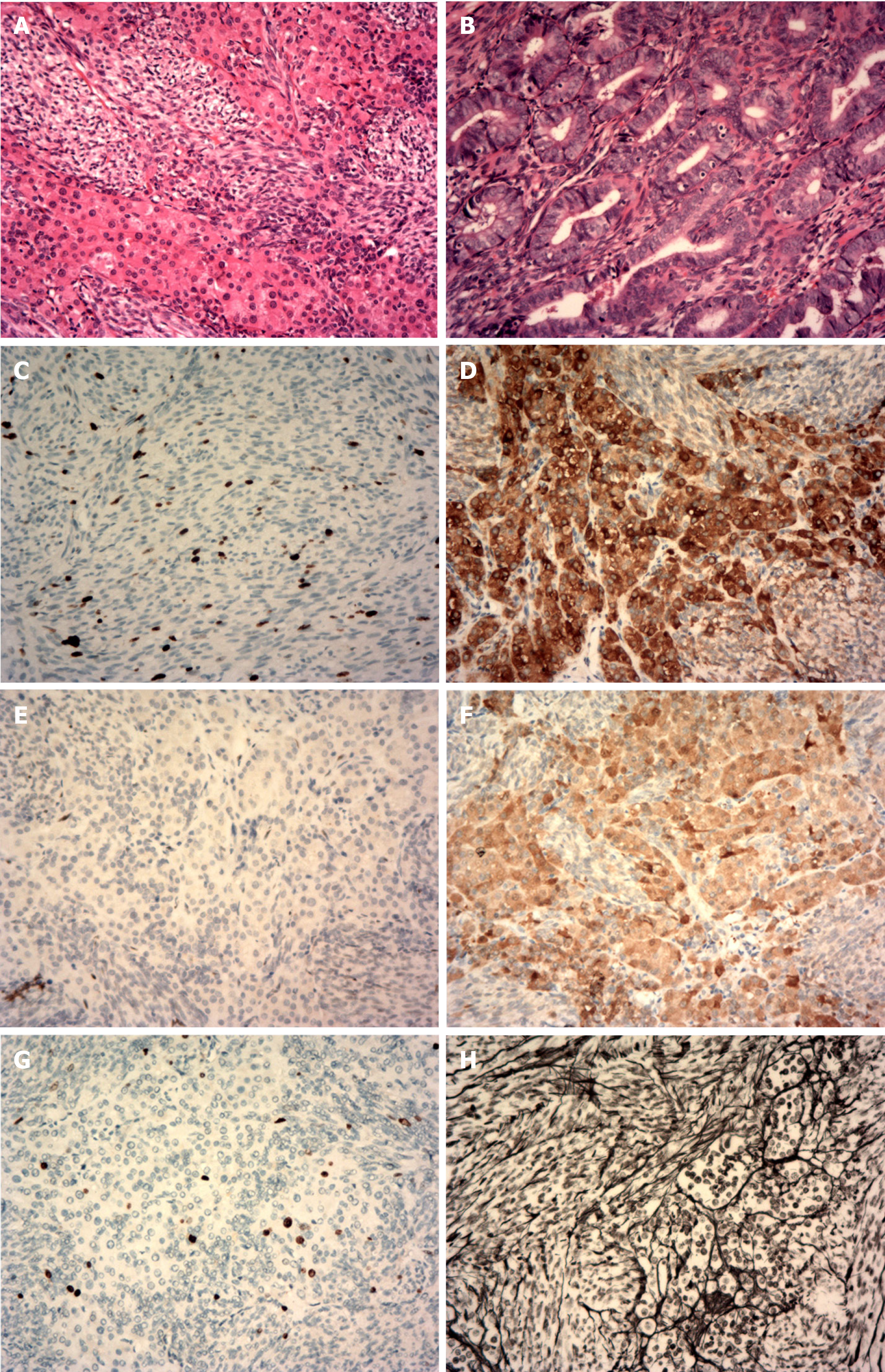

Histopathological examination of the surgical specimens with immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of right ovarian cellular fibroma with hilar cell hyperplasia, focal complex endometrial hyperplasia, multiple leiomyomas of the uterus, and chronic cervicitis. The following observations were made:

The tumor cells of the right ovarian lesion were observed to be spindle-shaped and bundle-like with sheet-like arrangement under a microscope, and the cells were densely arranged without obvious atypia. Eosinophilic cell nests with rich cytoplasm were visible in the focal area (Figure 3A). The densely arranged endometrial glands were hyperplastic, and some glandular lumens were irregular (Figure 3B). Immunohistochemistry revealed the following: cytokeratin (focal+, Figure 3C); inhibin (part+, Figure 3D); Wilm’s tumor protein (WT1, part+, Figure 3E); calretinin (+, Figure 3F); Ki-67 (approximately 10% +, Figure 3G); and net staining showed mostly surrounding single cells (Figure 3H).

The patient was diagnosed with endometrial complex hyperplasia, but the possibility of mild atypical hyperplasia could not be excluded after full-scale curettage using hysteroscopy was performed (performed on June 23, 2020).

The patient was diagnosed with right ovarian cellular fibroma with hilar cell hyperplasia, focal complex endometrial hyperplasia, multiple leiomyomas of the uterus, and chronic cervicitis after undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (performed on July 10, 2020).

Full-scale curettage using hysteroscopy was performed on June 23, 2020. Since atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium was not excluded and considering the patient’s age and operation history, we decided to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy after the fourth hysteroscopic curettage. TVUS was performed again before the operation and a 1.6 cm × 1.2 cm × 1.2 cm mass was observed in the right ovary. Laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed on July 10, 2020.

The patient recovered well after the fifth operation. The sex hormone levels on the first day after the fifth operation were as follows: E2, 22 pg/mL and Testo, 0.73 ng/mL; on the second day, they were E2, < 20 pg/mL and Testo, 0.30 ng/mL. The patient was discharged on the 5th day postoperatively, 2 and 6 mo after the operation, no abnormalities were observed in the outpatient review.

PMB, defined as uterine bleeding occurring after at least 12 mo of amenorrhea, is mainly caused by intrauterine sources, and a few cases are related to ovarian tumors. Clarke et al[1] found that, among 593 women with PMB, 18 (3.0%) had endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN), and 47 (7.9%) had endometrial cancer (EC). Women with recurrent PMB had higher risks of EIN and EC (4.5% and 10.1%, respectively) than those with an initial episode of PMB (0.5% and 5.1%, respectively; P = 0.002)[1]. Endometrial hyperplasia is usually caused by the continuous action of estrogen on the endometrium and is regarded as a precursor to EC. Hysteroscopy is now considered the gold standard for diagnosing and managing intrauterine lesions[2]. TVUS of postmenopausal women with endometrial thickness > 4 mm requires additional endometrial sampling for evaluation. For women with PMB, a negative tissue biopsy after a “blind” sampling of the endometrium is not considered the end point[3].

The endometrium gradually escalates from simple hyperplasia to complex hyperplasia and atypical hyperplasia due to long-term estrogen stimulation, which may develop into EC if not treated in time. The present case demonstrates the rare possibility of ovarian cellular fibroma as a precursor for estrogen excess leading to endometrial hyperplasia and PMB.

Ovarian fibromas are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the ovary, accounting for 4% of all ovarian tumors[4]. They occur mainly in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. The most common clinical manifestation of ovarian fibroma is an ovarian mass, sometimes accompanied by pleural effusion and ascites. Approximately 10% of ovarian fibromas are cellular fibromas, with an average age at onset of 51 years[5]; clinical manifestations tend to be benign with occasional local recurrence and low malignant potential. It usually presents as an ovarian mass, which may be accompanied by hemorrhage, edema, and cystic degeneration. Cystic degeneration usually forms a single cyst; in rare cases, it may be polycystic[6].

Unlike granular or theca cell tumors, ovarian fibromas rarely exhibit estrogenic activity. Chechia et al[4] retrospectively analyzed 24 cases of ovarian fibroma and fibrothecomas, which have no endocrine activity. Haroon et al[7] retrospectively analyzed 480 cases of ovarian sex cord-stromal tumor (SCST), including 98 cases of ovarian fibroma; of which one was associated with EC and another with endometrial hyperplasia, proving that these tumors have hormonal activity. Identifying whether ovarian fibromas have other concomitant components and/or hormonal activity may explain various clinical characteristics and histopathological findings. Our case presented with hilar cell hyperplasia alongside her other presentations, which increases the rate of androgen secretion. The levels of estrogen and androgen were significantly higher than normal and dropped to the normal range on the second day after surgery; estrogen may be directly secreted by tumors and/or transformed by androgens.

Ovarian fibromas are easily misdiagnosed as uterine fibroids since they are generally solid tumors. In the present case, TVUS eventually revealed an ovarian hypoechoic mass before the fifth operation. The ovarian mass should have existed at the time of the fourth operation, but it was not reported by ultrasound and imaging doctors. It was likely mistaken for a uterine fibroid, as the patient had several of those. Ovarian cellular fibroma is diagnosed using postoperative pathology. Its pathological characteristics tend to be observed microscopically, and the tumor cells are fusiform and dense, have 0-3 mitoses/10 high-power fields, do not exhibit obvious nuclear atypia, and are arranged in bundles, which may contain a small amount of sex cord components (partly with luteinized cells). It is surrounded by reticular fibers. Immunohistochemistry can show inhibin-α, calretinin, estrogen receptor, Prog receptor, etc. to varying degrees. The tumor immunohistochemistry result in our case is consistent with those reported in the literature. Ovarian cellular fibroma is also easily misdiagnosed as ovarian malignant tumor, especially when it occurs in both ovaries or is accompanied by pleural effusion, ascites, or elevated CA125 Levels. At the same time, ovarian fibroma should also be distinguished from ovarian granulosa cell tumor (GCT) and thecoma, which usually have estrogen activity. GCT usually secretes estrogens and inhibin, especially inhibin B[8]. Therefore, elevated serum inhibin B is regarded as a classic marker of GCT. However, Carballo et al[9] demon

Ovarian fibromas are treated with surgery. Laparoscopy facilitated shorter operation times than laparotomy, with no significant differences in perioperative complications occurring[10]. Perimenopausal or postmenopausal patients with ovarian cellular fibromas are recommended to undergo total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with long-term follow-up. In our case, the patient had recurrent vaginal bleeding 4 years ago, and estrogen level was higher than normal, although auxiliary examinations did not indicate ovarian mass, should we have recommended that the patient undergo prophylactic removal of the whole uterus and both fallopian tubes and ovaries to avoid subsequent vaginal bleeding and surgery?

PMB should never be ignored, however, the ideal sequence of investigation for a patient with PMB remains controversial[11]. Ovarian cellular fibroma occurs insidiously and may exhibit hormonal activity. Excessive or long-term serum estrogen stimulation of the endometrium may cause endometrial hyperplasia or even cancer, resulting in symptoms such as PMB. Therefore, early diagnosis, determination of a clear cause, and timely treatment are essential. Sex hormone testing is recommended for patients with recurrent PMB and endometrial thickening. If the estrogen level remains elevated even if imaging does not indicate an ovarian tumor, clinicians should first consider whether it may be associated with ovarian SCST. Once ovarian masses are found, they should be removed as soon as possible to prevent endometrial lesions formations, regardless of size. Further study is required to determine whether preventive removal of the whole uterus and bilateral fallopian tubes and ovaries should be recommended to women with elevated estrogen levels, repeated bleeding after menopause, and auxiliary examinations that do not reveal ovarian masses; it may avoid multiple subsequent curettage procedures, which are associated with physical and psychological burdens.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mais V, Plagens-Rotman K S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Clarke MA, Long BJ, Sherman ME, Lemens MA, Podratz KC, Hopkins MR, Ahlberg LJ, Mc Guire LJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Wentzensen N. Risk assessment of endometrial cancer and endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia in women with abnormal bleeding and implications for clinical management algorithms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:549.e1-549.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fagioli R, Vitagliano A, Carugno J, Castellano G, De Angelis MC, Di Spiezio Sardo A. Hysteroscopy in postmenopause: from diagnosis to the management of intrauterine pathologies. Climacteric. 2020;23:360-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manchanda R, Thapa S. An overview of the main intrauterine pathologies in the postmenopausal period. Climacteric. 2020;23:384-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chechia A, Attia L, Temime RB, Makhlouf T, Koubaa A. Incidence, clinical analysis, and management of ovarian fibromas and fibrothecomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:473.e1-473.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Irving JA, Alkushi A, Young RH, Clement PB. Cellular fibromas of the ovary: a study of 75 cases including 40 mitotically active tumors emphasizing their distinction from fibrosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Adad SJ, Laterza VL, Dos Santos CD, Ladeia AA, Saldanha JC, da Silva CS, E Souza LR, Murta EF. Cellular fibroma of the ovary with multiloculated macroscopic characteristics: case report. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:283948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haroon S, Zia A, Idrees R, Memon A, Fatima S, Kayani N. Clinicopathological spectrum of ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors; 20 years' retrospective study in a developing country. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gică C, Cigăran RG, Botezatu R, Panaitescu AM, Cimpoca B, Peltecu G, Gică N. Secondary Amenorrhea and Infertility Due to an Inhibin B Producing Granulosa Cell Tumor of the Ovary. A Rare Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carballo EV, Gyorfi KM, Stanic AK, Weisman P, Flynn CG, Kushner DM. Benign ovarian thecoma with markedly elevated serum inhibin B levels mimicking adult granulosa cell tumor. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2020;34:100658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cho YJ, Lee HS, Kim JM, Joo KY, Kim ML. Clinical characteristics and surgical management options for ovarian fibroma/fibrothecoma: a study of 97 cases. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;76:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Carugno J. Clinical management of vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2020;23:343-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |