Published online Nov 16, 2013. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i8.256

Revised: September 9, 2013

Accepted: October 16, 2013

Published online: November 16, 2013

Processing time: 106 Days and 14.3 Hours

We present a 29-year-old woman with a long history of attacks of migraine with and without visual aura. She was a heavy smoker (20 cigarettes/d) and was currently taking oral contraceptives. During a typical migraine attack with aura, she developed dysarthria, left brachial hemiparesis and hemihypoesthesia and brief and autolimited left clonic facial movements. Four hours after onset, vascular headache and focal sensorimotor neurological deficit were the only persisting symptoms and, on seventh day, she was completely recovered. Brain magnetic resonance imaging on day 20 after onset showed a subacute ischemic lesion in the right temporo-parietal cortex compatible with cortical laminar necrosis (CLN). Extensive neurological work-up done to rule out other known causes of cerebral infarct with CLN was unrevealing. Only ten of 3.808 consecutive stroke patients included in our stroke registry over a 19-year period fulfilled the strictly defined International Headache Society criteria for migrainous stroke. The present case is the unique one in our stroke registry that presents CLN related to migrainous cerebral infarction. Migrainous infarction can result in CLN.

Core tip: A 29-year-old migrainous woman developed dysarthria and focal sensorimotor neurological deficit during a typical migraine attack with aura. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed a right temporo-parietal ischemic lesion compatible with cortical laminar necrosis (CLN). The present case is the unique one in our stroke registry over a 19-year period that presents CLN related to migrainous cerebral infarction. Our case shows that CLN can be associated with cerebral ischemia due to migrainous infarction, an infrequent ischemic cerebral infarct of unusual etiology.

- Citation: Arboix A, González-Peris S, Grivé E, Sánchez MJ, Comes E. Cortical laminar necrosis related to migrainous cerebral infarction. World J Clin Cases 2013; 1(8): 256-259

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v1/i8/256.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i8.256

Cortical laminar necrosis (CLN) is an infrequent type of cortical infarction which causes a selective pannecrosis of the cerebral cortex (involving neurons, glia and blood vessels) while underlying white matter is completely or relatively spared[1,2]. It has been reported to be associated with hypoxic encephalopathy[3,4], hypoglycemic encephalopathy[5], status epilepticus[6], cerebral infarction[7] and rarely cerebral infarction due to migraine[8,9].

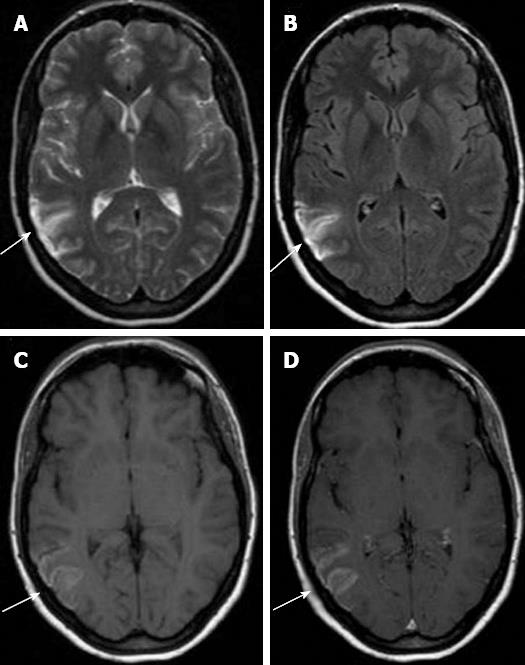

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) CLN is characterized by a high intensity cortical signal on T1-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (FLAIR) images, without signs of hemorrhage, which shows a typical curvilinear gyriform distribution, following the cerebral convolutions affected[1-3].

We report the case of a young female patient who suffered an unusual case of cerebral infarction secondary to a migrainous cerebral infarction manifested as CLN on brain MRI.

We present a 29-year-old woman with a long history of attacks of migraine (8 years) with and without visual aura. She was a heavy smoker (20 cigarettes/d for the last 4 years) and was currently taking oral contraceptives. At the age of 18 years, she had an ectopic pregnancy and a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was done. At the age of 20 years she had a voluntary abortion. She was diagnosed with anxiety disorder and was taken alprazolam (0.50 mg/d for 3 years) under the periodic supervision of his psychiatrist. During a typical migraine attack with visual aura symptomatology, she developed dysarthria, left brachial hemiparesis, left hemihypoesthesia and autolimited left clonic facial movements (< 1 min lasting). Four hours after onset, severe holocraneal vascular headache persisted along with nausea and vomiting and mild left brachial sensorimotor deficit [magnetic resonance spectroscopy (mRS) = 2, National Institute of Health stroke scale (NIHSS) = 2]. She had neither nucal rigidity nor semiology of meningeal syndrome. The patient was not treated with triptans or any other drugs which might have led to vasoconstriction.

The following investigations were normal or unremarkable: chest roentgenography, 12-lead electrocardiography, brain computed tomography scan, two-dimensional echocardiography, and Doppler ultrasonography of the supra-aortic trunks, complete hematological screening, routine biochemical profile, urinalysis, serology for syphilis, immunologic blood test (including antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens, lupus anticoagulant, Immunoglobulin G and Immunoglobulin M anticardiolipin antibodies, rheumatoid factor), basic hemostasis study and hypercoagulable panel (including protein C and S, antithrombin III, factor V Leiden mutation and homocysteine). The use of cocaine or other substances with vasoconstrictive properties as amphetamines was ruled out.

The clinical course was favorable. A gradual regression of symptomatology was observed and, seven days after onset, focal neurological deficit was completely recovered (mRS = 0, NIHSS = 0).

Brain MRI on day 20 after the migraine attack showed increased signal on FLAIR, T-1 and T2-weighted sequences and diffusion images involving the right temporo-parietal cortex compatible with subacute infarct with CLN, showing a minimum enhancement post-contrast (Figure 1). Intracranial MR angiography was normal and negative for dural sinus thrombosis. Electroencephalography was non-epileptiform, showing only right hemisphere slowing.

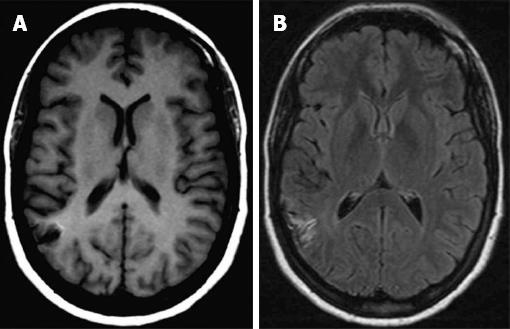

At the 9th and 18th month follow-up control, brain MRI revealed that the characteristic cortical high signal intensity on T1 and FLAIR images progressively faded (Figure 2). Hemosiderin due to chronic hemorrhage was never demonstrated. The patient remained entirely asymptomatic.

CLN as a presenting neuroimaging sign of migrainous stroke has been infrequently reported[8,9]. CLN has been associated with cerebral hypoxia, metabolic disturbances, drugs and infections[1-7]. CLN usually shows characteristic cortical high intensity on T1-weighted images from 2 wk to 2 years after ischemia and on FLAIR sequences, hypersignal appears a little later but remains longer[1,2,10].

Furthermore, the blood-brain barrier breakdown due to the necrosis of the blood vessels results in the curvilinear “gyriform” enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced scans typically seen in these cortical infarctions[6-8]. Hyperintense signal on T1-weighted images can reflect the presence of any of the following substances: hemoglobin, fat, melanin, paramagnetic substances or protein-rich fluid[5-7]. The T1 hyperintensity observed in CLN is not secondary to hemorrhagic transformation of cerebral ischemia and is thought to be due to the selective neuronal damage followed by higher concentration of proteins (and other macromolecules), glial cell proliferation and deposition of fat laden macrophages in the cortical area affected, that enhance relaxivity by restricting the motion of water molecules, thus causing T1 shortening[4-7,10].

Little is known about the frequency of association of CLN and migrainous stroke, but the present case report is compatible with CLN related to migrainous cerebral infarction. Only 10 of 3.808 consecutive stroke patients included in our stroke data bank over a 19-year period fulfilled the criteria defined by the International Headache Society for migrainous stroke and in whom other causes of stroke were ruled out[11]. Migrainous stroke is a known etiology of cerebral infarction of unusual case[12]. The present case is the unique one in our stroke registry that presents CLN related to migrainous cerebral infarction.

To the best of our knowledge we have only found two similar case-reports of migrainous infarction involving CLN: the study of Liang et al[11] including a case report of a 57-year-old white female with migrainous infarct with appearance of CLN on MRI[8] and also, a report by Black et al[12] involving possible CLN in the setting of familial hemiplegic migraine in a patient with Erdheim-Chester disease (a rare non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis).

The patient present initial autolimited left clonic facial seizures which can be explained by the involvement of the cerebral cortex related to CLN. Seizures in acute ischemic stroke occur in approximately 5% of patients and are related to involvement of the cerebral cortex or to very large strokes[13].

Our patient fulfilled the strict diagnostic criteria for migraine-induced stroke of the International Headache Society[14,15], which include: (1) the patient has previously fulfilled criteria for migraine with aura; (2) the neurological deficit is manifested in the exactly vascular distribution as the aura, persisting for more than 60 min, and is associated with an ischemic brain lesion in a suitable territory demonstrated by neuroimaging; and (3) all other potential causes of ischemic stroke with CLN have to be ruled out by appropriate investigations. Migrainous stroke occurs more frequently in women and in patients ≤ 45 years of age[11]. The heavy smoking history and the use of oral contraceptives are risk factors for migrainous cerebral infarction.

The physiopathology of migrainous stroke remains controversial. Potential mechanisms of migrainous infarction include vasospasm, hypercoagulability and vascular changes related to cortical spreading depression[16,17]. Endothelial dysfunction, a process mediated by oxidative stress, may be a cause or a consequence of migraine, thus explaining the relationship of migraine to vascular factors and stroke[16-18]. Therefore, all this processes may be considered in the genesis of CLN.

The present case shows that CLN can be considered a rare potential cause of migrainous infarction, an ischemic cerebral infarct of unusual etiology.

We thank Drs Joan Massons, Montserrat Oliveres, and Cecilia Targa for their assistance in this study.

P- Reviewers: Brigo F, Juan DS S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Siskas N, Lefkopoulos A, Ioannidis I, Charitandi A, Dimitriadis AS. Cortical laminar necrosis in brain infarcts: serial MRI. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:283-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Serrano-Pozo A, González-Marcos JR, Gil-Peralta A. Cortical laminar necrosis caused by cerebral infarction. Neurologia. 2006;21:258-259. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Serrano M, Ara JR, Fayed N, Alarcia R, Latorre A. [Hypoxic encephalopathy and cortical laminar necrosis]. Rev Neurol. 2001;32:843-847. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sethi NK, Torgovnick J, Macaluso C, Arsura E. Cortical laminar necrosis following anoxic encephalopathy. Neurol India. 2006;54:327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Yoneda Y, Yamamoto S. Cerebral cortical laminar necrosis on diffusion-weighted MRI in hypoglycaemic encephalopathy. Diabet Med. 2005;22:1098-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Donaire A, Carreno M, Gómez B, Fossas P, Bargalló N, Agudo R, Falip M, Setoaín X, Boget T, Raspall T. Cortical laminar necrosis related to prolonged focal status epilepticus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:104-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Komiyama M, Nakajima H, Nishikawa M, Yasui T. Serial MR observation of cortical laminar necrosis caused by brain infarction. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:771-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kinoshita T, Ogawa T, Yoshida Y, Tamura H, Kado H, Okudera T. Curvilinear T1 hyperintense lesions representing cortical necrosis after cerebral infarction. Neuroradiology. 2005;47:647-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Arboix A, Massons J, García-Eroles L, Oliveres M, Balcells M, Targa C. Migrainous cerebral infarction in the Sagrat Cor Hospital of Barcelona stroke registry. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arboix A, Bechich S, Oliveres M, García-Eroles L, Massons J, Targa C. Ischemic stroke of unusual cause: clinical features, etiology and outcome. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liang Y, Scott TF. Migrainous infarction with appearance of laminar necrosis on MRI. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:592-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Black DF, Kung S, Sola CL, Bostwick MJ, Swanson JW. Familial hemiplegic migraine, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and Erdheim-Chester disease. Headache. 2004;44:911-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Arboix A, Comes E, García-Eroles L, Massons JB, Oliveres M, Balcells M. Prognostic value of very early seizures for in-hospital mortality in atherothrombotic infarction. Eur Neurol. 2003;50:78-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia. 1988;8 Suppl 7:1-96. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Headache Classfication Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24 Suppl 1:9-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 798] [Cited by in RCA: 2427] [Article Influence: 115.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kurth T. Migraine and ischaemic vascular events. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:965-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tietjen EG. Migraine and ischaemic heart disease and stroke: potential mechanisms and treatment implications. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:981-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bousser MG, Welch KM. Relation between migraine and stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:533-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |