Published online Aug 16, 2013. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i5.166

Revised: July 2, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: August 16, 2013

Processing time: 98 Days and 9 Hours

In the case presented here, everolimus was administered after first line therapy with sunitinib in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. The safety profile was excellent. The prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) obtained with everolimus in this case is of peculiar interest, as it is a multiple of the median PFS obtained in with everolimus in the regulatory trial. Such finding suggests that a subset of patients with renal cell carcinma may particularly benefit from everolimus.

Core tip: Everolimus (RAD001) is an orally administered inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Everolimus is recommended for the second line therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma after a Tyrosine kinase inhibitor. In the case presented here, everolimus was administered after first line therapy with sunitinib. The prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) obtained with everolimus in this case is of peculiar interest, as it is a multiple of the median PFS obtained in with everolimus in the regulatory trial.

- Citation: Virtuoso A, Policastro T, Izzo M, Federico P, Buonerba C, Rescigno P, Di Lorenzo G. Long lasting response to second-line everolimus in kidney cancer. World J Clin Cases 2013; 1(5): 166-168

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v1/i5/166.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i5.166

After years of disappointing results obtained with the use of cytokines in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)[1,2], the therapeutic armamentarium for the treatment of this disease has recently dramatically expanded to include a variety of multiple agents, such as everolimus, sunitinib, sorafenib, bevacizumab, temsirolimus, and pazopanib, each having a distinct mechanism of action[3]. Contrary to chemotherapy agents, which simply interfere with cellular replication, these six novel drugs, at the present time approved both in Europe and in the United States, are classified as “targeted agents” because of their ability to interfere with the intra- or extra-cellular signaling of cancerous cells, via enzyme inhibition or blockage of growth factors. While bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF), sunitinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib inhibit several tyrosine kinase receptors (TKRs), such as the VEGF receptor, c-KIT, BRAF and others[3]. On the other hand, temsirolimus and everolimus exert their anti-tumour effect through inhibition of the universal pathway of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)[3]. The process of identifying the optimal sequence of administration of these agents is complex and requires execution of large phase III trials. Currently, sorafenib is the standard therapy after unsuccessful treatment with cytokines[4] and sunitinib is the standard first-line treatment for mRCC[5]. At present, the only approved targeted agent for second-line treatment of mRCC after failure of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) is everolimus (Table 1). This approval was based on the strong results of the large, well-conducted RECORD-1 trial[6]. The case reported here is highly explicative of the excellent efficacy and safety profile of everolimus employed as second-line treatment of mRCC after failure of a TKI.

| Drug | FDA approval in kidney cancer for | EMEA approval in kidney cancer for |

| Everolimus | Treatment of patients with advanced RCC after failure of treatment with sunitinib or sorafenib | Advanced renal cell carcinoma (kidney cancer that has started to spread). It is used when the cancer has progressed during or after previous treatment with a medicine that targets vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Sunitinib | The treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma | Metastatic renal cell carcinoma, a type of kidney cancer that has spread to other organs |

| Bevacizumab | The treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in combination with interferon-α | Advanced or metastatic kidney cancer, in combination with interferon-α-2a |

| Sorafenib | The treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma | Advanced renal cell carcinoma when anticancer treatment with interferon-α or interleukin-2 has failed or cannot be used |

| Temsirolimus | The treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma | advanced renal cell carcinoma. “Advanced” means that the cancer has started to spread |

| Pazopanib | The treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma | Advanced renal cell carcinoma. It is used in patients who have not received any previous treatment or in patients who have already been treated for their advanced disease with anticancer medicines called “cytokines”. “Advanced” means that the cancer has started to spread. |

| Axitinib | Treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma after failure of one prior systemic therapy | Treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma when treatment with Sutent (sunitinib) or “cytokines” has failed |

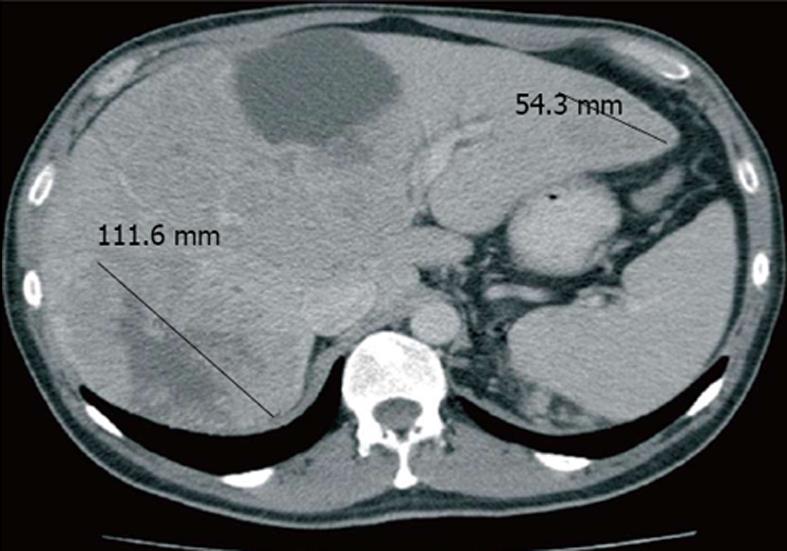

The subject of this report is a male patient with a history of cigarette use and hypertension controlled with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. In 2006, at the age of 65 years, the patient underwent left radical nephrectomy with lymphadenectomy. Histological analysis showed the presence of a clear cell carcinoma, presenting intravascular emboli, but no lymph node metastasis and tumour necrosis. According to the radiographic and pathological staging procedures performed, the patient was affected by stage 3 disease (pT3aN0M0G3). The patient’s World Health Organization (WHO) performance status was 1. On the basis of staging, grading, and clinical data, the patient could be considered at a high risk of relapse[7] and underwent a close clinical and radiological follow up performed by his attending urologist. In March 2009, the patient presented a fever and a rash on the face and lamented intense fatigue and flank pain located on the right side. A computed tomography (CT) whole body scan with contrast showed the presence of multiple liver metastases, one of which presented a maximum diameter greater than 10 cm (Figure 1). Considering that haemoglobin levels were 10 g/dL and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were more than twice the upper limit of normal, with normal serum calcium levels, the WHO performance status of 1 and a disease-free time of approximately 3 years, the patient was classified as being at intermediate prognosis.

In accordance with current available evidence for metastatic kidney cancer[3], the patient was treated with first-line sunitinib, which was administered according to the standard approved regimen (50 mg/d; 4 wk on, 2 wk off), with a close monitoring of arterial blood pressure, thyroid function, as well as blood count and chemistry. Treatment was well tolerated. The patient presented a single event of Grade 3 leukopenia, Grade 1 mucositis, mild skin discoloration and Grade 1 diarrhoea. In October 2009, after four cycles of sunitinib, the patient showed signs of progressive disease indicated by the whole body CT scan, with multiple lateral cervical adenopathies (maximum 26 mm), a thyroid nodule (30 mm), subpleural lesions in left upper lobe (maximum 6 mm), multiple pulmonary hilar adenopathies (maximum 20 mm) and retro-crural adenopathies (maximum 24 mm). An echo-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) confirmed the presence of thyroid metastases. Following the patient’s diagnosis, everolimus treatment was initiated which was obtained for compassionate use at the dose of 10 mg/d, every day (1 cycle = 30 d), with periodic clinical, radiological, and blood chemistry monitoring.

After 4 mo, the thyroid nodule and laterocervical lymphnodes showed a partial response according to the revised Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumours and was documented by CT scan, which was further confirmed by ecography and physical examination. Liver disease appeared to be stable on CT scan and treatment was well tolerated. The patient only reported a mild itch since the completion of the fourth cycle, which completely regressed with the administration of antihistamines. The patient also experienced an episode of Grade 1 thrombocytopenia during the third, sixth, and eighth cycle, a Grade 1 hypercholesterolaemia, and an acne-like rash during the fifth cycle which was treated with emollient lotions and clindamycin.

The patient continued everolimus until February 2011, receiving a total of 16 cycles of treatment until the patient presented a marked clinical deterioration with progressive disease in the liver and lymph nodes detected by CT scan. The patient received best supportive care recommended for patients with deteriorating performance status and died four months after the interruption of everolimus.

The RECORD-1 trial, which compared everolimus to placebo in a population of pretreated mRCC, indicated that median progression-free survival was 4.9 mo in the everolimus group (95%CI: 4.0-5.5), more than double the duration obtained in the placebo group[6]. The progression-free survival time of this case appears exceptionally prolonged. This notable effect was obtained in addition to an excellent toxicity profile. This case indicates that there is a subset of patients for whom everolimus may work better than other targeted therapies such as sunitinib. Identification of this peculiar subset via histological, serum, or radiographic markers, may have substantial clinical implications. Given the current lack of validated markers, we are unable to provide a plausible explanation for the prolonged disease control obtained in our patient. It is also difficult for us to explain the reasons why a disease which had been stable for several months presented such a rapid progression, although it is clear that selection of resistant neoplastic clones can manifest itself as an aggressive disease.

P- Reviewers Desai DJ, Kulis T, Papatsoris AG S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Gleave ME, Elhilali M, Fradet Y, Davis I, Venner P, Saad F, Klotz LH, Moore MJ, Paton V, Bajamonde A. Interferon gamma-1b compared with placebo in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. Canadian Urologic Oncology Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1265-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Negrier S, Escudier B, Lasset C, Douillard JY, Savary J, Chevreau C, Ravaud A, Mercatello A, Peny J, Mousseau M. Recombinant human interleukin-2, recombinant human interferon alfa-2a, or both in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. Groupe Français d’Immunothérapie. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1272-1278. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Di Lorenzo G, Buonerba C, Biglietto M, Scognamiglio F, Chiurazzi B, Riccardi F, Cartenì G. The therapy of kidney cancer with biomolecular drugs. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36 Suppl 3:S16-S20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 737] [Cited by in RCA: 691] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Solska E, Desai AA. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3788] [Cited by in RCA: 3764] [Article Influence: 209.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Kim ST. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4472] [Cited by in RCA: 4479] [Article Influence: 248.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, Grünwald V, Thompson JA, Figlin RA, Hollaender N. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma : final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 2010;116:4256-4265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 868] [Cited by in RCA: 926] [Article Influence: 61.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lam JS, Shvarts O, Leppert JT, Pantuck AJ, Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS. Postoperative surveillance protocol for patients with localized and locally advanced renal cell carcinoma based on a validated prognostic nomogram and risk group stratification system. J Urol. 2005;174:466-472; discussion 472; quiz 801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |