Published online Apr 16, 2013. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i1.56

Revised: March 26, 2013

Accepted: March 28, 2013

Published online: April 16, 2013

Processing time: 88 Days and 17.9 Hours

Spinal cord compression (SCC) caused by cervical spinal canal invasion of a pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma metastasis has never been reported previously. A 59-year-old man, with a history of pulmonary carcinosarcoma, developed over several weeks important neck swelling. Admitted to our division with severe tetraparesis he underwent a cervical spine computed tomography scan that showed a large cervical mass measuring 11 cm × 27 cm × 17 cm with SCC, extending from the occiput to C7. Emergency spinal cord decompression was performed leading to minor neurological improvement. Poor outcome was due to the unusual clinical sign that led to late diagnosis and treatment.

Core tip: Spinal cord compression (SCC) caused by cervical spinal canal invasion of a pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma metastasis has never been reported previously. A 59-year-old man, with a history of pulmonary carcinosarcoma, developed over several weeks important neck swelling. Admitted to our division with severe tetraparesis he underwent a cervical spine computed tomography scan that showed a large cervical mass measuring 11 cm × 27 cm × 17 cm with SCC, extending from the occiput to C7. Emergency spinal cord decompression was performed leading to minor neurological improvement. Poor outcome was due to the unusual clinical sign that led to late diagnosis and treatment.

- Citation: Costi E, Roca E, Spanu F, Nicolosi F, Nodari G, Fontanella M, Panciani PP. Can neck swelling lead to spinal cord compression? World J Clin Cases 2013; 1(1): 56-58

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v1/i1/56.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i1.56

Spinal cord compression (SCC) is a well-known occurrence in cancer patients that can lead to permanent neurologic impairment. Prompt diagnosis is mandatory and surgery should be performed at the onset of symptoms. Up to 30% of cancer patients develop metastases (mts) in the spine and SCC is generally observed in almost 15% of them. In adults, SCC is mainly due to solid tumors and lung cancers are responsible for 15% to 20% of cases. Thoracic and lumbosacral account for about 75% of the locations, whereas cervical mts are less common[1]. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas (PSC) are rare and SCC in case of PSC has never been observed. In this article we report a case of neck swelling and progressive neurological impairment in a patient affected by pulmonary carcinosarcoma.

A 59-year-old man with a history of pulmonary lobectomy performed 6 mo before for carcinosarcoma presented over a period of several weeks progressive neck swelling (Figure 1). Several physicians evaluated the cervical mass, but no further investigations were prescribed. At last the patient developed severe tetraparesis and was admitted to our Neurosurgical Division.

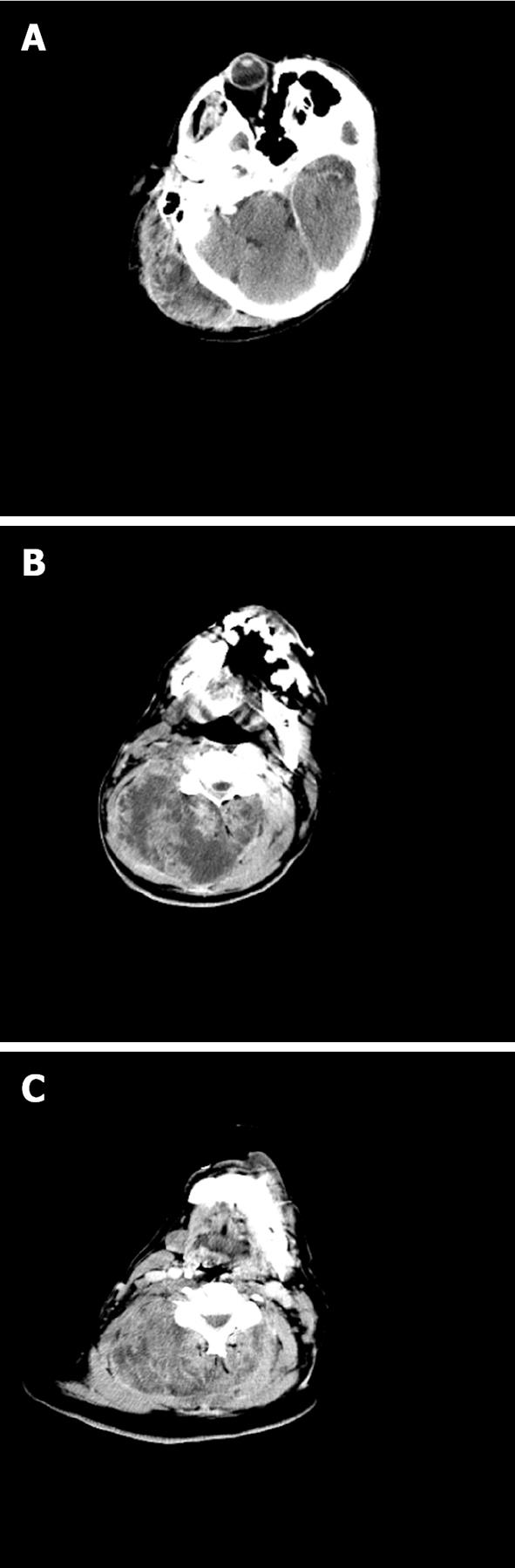

An emergent cervical spine computed tomography (CT) scan which showed (Figure 2) the presence of a mass measuring 11 cm × 27 cm × 17 cm, extending from the occiput to C7 and antero-laterally to the right. The lesion entered the spinal canal between C1 and C2 with marked SCC extending caudally for 7 cm. The patient underwent partial tumor debulking and laminectomy from C1 to C4 with complete spinal cord decompression resulting in a minor neurological recovery and persistence of severe paraperesis. The metastatic lesion opened itself a breach in the ligamentum flavum between C1 and C2 entering the spinal canal, compressing the spinal cord without any dural or bony infiltration.

The histopathological findings showed the presence of atypical cellular elements with a mixture of carcinomatous and mesenchymal components. The epithelial component showed marked nuclear pleomorphism and a mitotic index > 15 × 10 high-power fields (HPF); the cells of the stromal component were also characterized by marked pleomorphism and high mitotic index > 15 × 10 HPF. Immunohistochemical investigations have shown intense and diffuse positivity for EMA (Dako) and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (Dako) in the cells of the epithelial component but not in those of the spindle stromal component. The positivity for vimentin (Menarini) was found for the elements of both cellular components. The spindle cells of the stromal component also tested negative for smooth muscle actin (Sigma), S-100 (Dako) and myosin (Dako). The initial post-oprative stay was uneventful and the patient was transferred to the Rehabilitation Division of our Hospital.

Pulmonary carcinosarcoma is a rare tumor that accounts for 0.3% to 1% of all pulmonary cancers, being a subgroup of PSC[2]. Currently, PSC are defined as poorly differentiated non-small-cell carcinomas containing a component with sarcoma or sarcoma-like (spindle or giant cell) component. The recent estabilishment of World Health Organization criteria classify pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma into carcinosarcoma, pleomorphic carcinoma, and spindle cell carcinoma[3]. On the basis of morphologic, behavioral, and genotypic/phenotypic attributes PSCs are segregated into a distinct clinicopathologic entity.

The sarcomatous or sarcomatoid component of these tumors probably derives from the activation in carcinoma cells of an epithelial-mesenchymal transition program leading to sarcomatous transformation or metaplasia (conversion paradigm)[4]. The sarcomatous component involves poorly differentiated osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or rhabdomyosarcoma.

The carcinomatous component is non-small-cell lung carcinoma, including squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma. The clinical characteristics, preoperative diagnostic methods, and prognostic factors of the pulmonary carcinosarcoma are still not completely understood.

Metastatic disease is frequent and it is most common to lymph nodes, followed by adrenal glands, kidneys, bones, liver and rarely brain. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of cervical metastasis from lung carcinosarcoma, with invasion of the spinal canal and compression of the spinal cord.

The metastatic carcinosarcoma showed high aggressiveness that led to the rapid onset of SCC. A fairly general symptomatology, cervical pain and fatigue, led to late diagnosis of spinal canal invasion and SCC leading to the development of a serious neurological condition before adequate diagnostic tests were performed. Therefore, it is important to achieve an early diagnosis to prevent SCC and tardive onset of severe symptoms. In this case neck magnetic resonance imaging would have been the best diagnostic imaging study for the correct visualization of the lesion’s relationship with the surrounding structures but wasn’t performed because the exam was not available at the time of presentation.

Considering the rapid onset of tetraparesis and the short amount of time between the onset and diagnosis we decided to perform emergent spinal cord decompression to allow the best neurological recovery possible for the patient leaving staging momentarily in stand-by. Unfortunately only partial neurologic recovery was obtained and the patient had severe paraparesis by post-operative day 4.

Therapeutic strategies are few, and there is limited information on treatment options such as systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nevertheless, the aggressive nature and poor differentiation of this tumor render the treatment difficult resulting in poor prognosis.

In conclusion, in case of diagnosis of pulmonary carcinosarcoma, vertebral or paravertebral metastases should always be considered in order to avoid irreversible neurological damage, moreover if a fairly aspecific physical finding such as neck swelling is observed. Therefore, a close follow-up is mandatory in order to undertake all possible therapeutic strategies ahead of time.

P- Reviewers Anazawa U, Armstrong N, Alimehmeti R S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Penas-Prado M, Loghin ME. Spinal cord compression in cancer patients: review of diagnosis and treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2008;10:78-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Davis MP, Eagan RT, Weiland LH, Pairolero PC. Carcinosarcoma of the lung: Mayo Clinic experience and response to chemotherapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:598-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huwer H, Kalweit G, Straub U, Feindt P, Volkmer I, Gams E. Pulmonary carcinosarcoma: diagnostic problems and determinants of the prognosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10:403-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, De Pas T, Galetta D, Veronesi G, Spaggiari L, Manzotti M, Fumagalli C, Bresaola E, Nappi O. Review article: pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: a practical overview. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:103-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |