Published online Apr 16, 2013. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i1.41

Revised: January 13, 2013

Accepted: February 7, 2013

Published online: April 16, 2013

Processing time: 96 Days and 4.1 Hours

We report on a 74-year-old patient with recurrent cholangitis and a large juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum. Despite drainage of the common bile duct by an endoscopically placed stent, the elevated liver enzymes normalized only partially. To rule out other possible causes of liver injury, a percutaneous liver biopsy was done. After the liver biopsy the patient developed fulminant septic shock and died within 24 h. We discuss the possible causes of the septic shock following percutaneous liver biopsy in our patient and give a concise overview of the literature.

Core tip: This case report deals with a patient in whom percutaneous liver biopsy was performed for further work-up of elevated liver enzymes. Immediately after biopsy, the patient developed fulminant sepsis and died. Possible reasons that might have caused sepsis in this patient as well as strategies to prevent sepsis/infection following percutaneous liver biopsy are discussed.

- Citation: Claudi C, Henschel M, Vogel J, Schepke M, Biecker E. Fulminant sepsis after liver biopsy: A long forgotten complication? World J Clin Cases 2013; 1(1): 41-43

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v1/i1/41.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i1.41

Percutaneous liver biopsy is an important diagnostic tool for the evaluation of liver disease. It is considered save with an overall mortality and morbidity rate of 0.015% and 0.29%, respectively[1]. The most important complication is bleeding related to liver biopsy with an incidence of 0.016%[2]. Infectious complications are nowadays considered as extremely rare[3]. We report on a patient with fulminant sepsis following percutaneous liver biopsy.

A 74-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital for further diagnostic work-up of recurrent episodes of cholangitis with fever and elevated liver enzymes. A year ago the patient had undergone cholecystectomy because of cholecystitis. The further medical history was remarkable for a stroke without neurological residuals and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. The patient was one a dose of 100 mg aspirin per day, which was stopped 7 d prior biopsy.

The laboratory work-up (Table 1) revealed elevated liver enzymes and a slight elevation of inflammatory markers. Sonography of the liver displayed mild intra- and extrahepatic cholestasis. Since endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed a large juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum, we thought that the recurrent bouts of cholangitis were, at least in part, caused by an intermittent obstruction of the bile flow and ascending bacterial infection caused by the diverticulum.

| Firstpresentation | Before percutaneousliver biopsy | |

| GGT (U/L) | 641 (10-71) | 283 (10-71) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 181 (40-129) | 131 (40-129) |

| ALT (U/L) | 109 (10-41) | 25 (10-41) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.4 (0.1-1.1) | 1.5 (0.1-1.1) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 54.3 (0.0-0.5) | 9.4 (0.0-0.5) |

We performed an ERCP and found a moderate dilated common bile duct (9 mm). A 7 Fr double pigtail plastic-stent was therefore placed in the common bile duct to ensure drainage. To minimize the risk of ascending biliary infections, a papillotomy was not performed. During the procedure we observed a short episode of flush. After the ERCP the patient developed chills and fever, which resolved promptly with antibiotic treatment.

Following stent implantation the elevated liver enzymes declined but did not fully normalize (Table 1). Since ultrasound showed that the intra- and extra-hepatic cholestasis had completely resolved, we employed an extended laboratory work-up to exclude autoimmune or viral liver disease.

Autoantibodies [antineutro-phil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-nuclear, antimitochondrial autoantibodies, smooth muscle antibodies, anti-liver kidney microsomal] as well as immunoglobulines, ferritin and markers of viral liver disease were unremarkable.

To rule-out ANCA-negative primary sclerosing cholangitis or toxic liver damage we performed a percutaneous liver biopsy. The biopsy was carried out under sterile conditions with a Menghini needle (Hepafix, Braun Melsungen, Germany) after local anesthesia with Scandicaine. The laboratory tests prior liver biopsy (Table 1) showed neither clotting abnormalities nor elevated markers of inflammation like white blood cell count and C-reactive protein.

Immediately after the biopsy the patient had a short episode of flush, lasting a few seconds only.

One hour after the biopsy, the patient developed chills and a temperature of 39.6 °C. Blood pressure dropped to 90/50 mmHg. Chest X-ray at this moment showed no abnormalities. Sonography of the liver revealed no bleeding or other abnormalities. The patient was transferred to an intensive care unit, blood cultures were taken immediately after admission and antibiotic treatment with Piperacillin/Tazobactam was started. Even though the patient developed fulminant sepsis with multi-organ failure.

Despite invasive ventilation, continuous veno-venous haemofiltration, administration of fresh frozen plasma and catecholamines the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly and he died 24 h after the liver biopsy in fulminant septic shock.

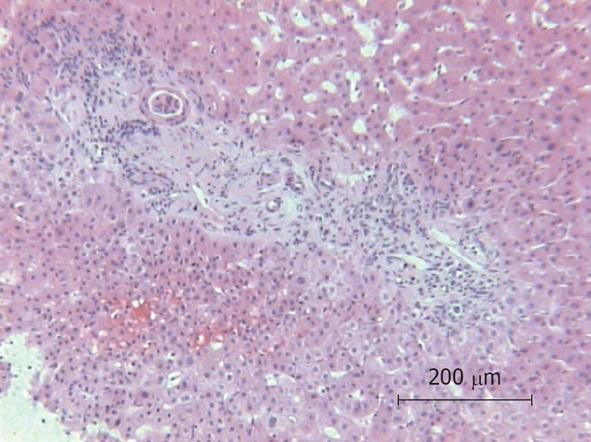

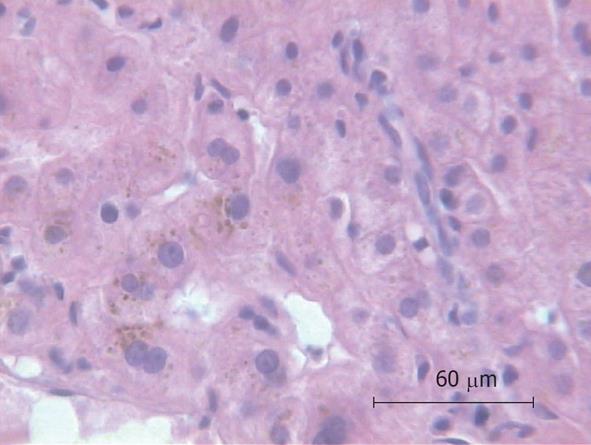

Because of the unexplained sepsis and the rapid deterioration of the patient’s condition after liver biopsy, an autopsy was performed. The autopsy demonstrated cholangitis but the puncture side and canal showed no abnormalities. Another infection site from which a bacterial sepsis could have been arose was not found. The histology of the liver specimen revealed chronic sclerosing cholangitis (Figures 1 and 2). There were no signs of toxic or other liver disease.

In the blood cultures that were taken 6 h after liver biopsy Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus mirabilis, Citrobacter braakii and Citrobacter freundii were found.

In our report, we describe a patient with fatal septic shock following percutaneous liver biopsy.

Liver biopsy is considered a safe procedure with complications in only 0.29% of cases[1]. The most important complications are pain and haemorrhage. Infrequent complications are shock, pulmonary embolism, arteriovenous fistula, haemobilia and ileus[4]. Infectious complications are considered as extremely rare[3].

Transient bacteremia following liver biopsy has an estimated incidence of 2% to 13%[5-7]. Most often only single microorganisms like Escherichia coli (E. coli) or Klebsiella spp. are found. However, clinically evident infectious complications following liver biopsy are considered a rare event. In a large retrospective analysis of 68 276 biopsies, the risk of infectious complications was approximately 1 in 10 000 liver biopsies[3].

To our best knowledge, there have been no published cases of sepsis following percutaneous liver biopsy in the last 15 years. In contrast, looking back two or three decades, septicemia following liver biopsy was described by several authors. Morris et al[8] reported fever and/or a positive blood culture in 3 out of 125 patients who underwent liver biopsy. LoIudice et al[4] found three patients with septicemia following liver biopsy in a series of 797 patients. Murray et al[9] as well as Navarro et al[10] published each one case report of patients with sepsis following liver biopsy. E. coli was found in the blood culture of most patients. Blood cultures positive for Streptococcus viridans, Klebsiella spp. and Clostridium welchii have also been reported. In the majority of the affected patients, liver biopsy revealed cholangitis or pericholangitis as the underlying disease. Large bile duct obstruction without cholangitis does not seem to be a risk factor for sepsis following liver biopsy[8]. These findings were emphasized by a study of 950 liver biopsies in 136 patients who had undergone liver transplantation[11]. The authors found infectious complications in six patients. Of these six patients, five had undergone choledochojejunostomy. Blood cultures of the affected patients were positive for E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Streptococcus faecium, Clostridium spp. and Enterobacter aerogenes. None of the five patients with choledochojejunostomy and infectious complications after biopsy had clinically evident signs of cholangitis before liver biopsy. Biliary obstruction was excluded in all patients by a T-tube or transhepatic cholangiogram. Since mainly microorganisms of the enteric flora were found, the authors concluded that due to the choledochojejunostomy, an enteric flora without clinically evident signs of infection colonized the transplanted liver.

Another group published conflicting results. They retrospectively compared 46 liver transplant patients with choledochojejunostomy with a total of 192 liver biopsies with 46 liver transplanted patients with choledochocholedochostomy with a total of 118 biopsies. There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding infectious complications[12]. The authors tried to explain the conflicting findings by a difference in the length of the small bowel segment used for the choledochojejunostomy.

One could only speculate why there have been no cases of sepsis following liver biopsy reported in the last years. Most likely-due to advances in imaging and laboratory methods in recent years-the majority of patients with cholangitis are correctly diagnosed without a liver biopsy and hence biopsy is nowadays seldom performed in patients with cholangitis.

Although sepsis following liver biopsy is considered a rare event, the pathogenetic relationship between liver biopsy and septic shock appears well substantiated in our patient.

At the time of the liver biopsy, the patient had no clinically or laboratory evident signs of cholangitis, nor was biliary obstruction present. Nevertheless, autopsy and the liver biopsy revealed cholangitis. In addition, the blood cultures were positive for bacteria, which are typically found in cholangitis. We hypothesize that the patient had recurrent bouts of ascending cholangitis caused by biliary obstruction due to the large juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum. The liver biopsy then induced propagation of infection by establishing the communication between the infected focus and the blood vessels.

To avoid septic complications in patients with suspected cholangitis undergoing liver biopsy in the future, antibiotic prophylaxis prior biopsy in these patients should be discussed.

P- Reviewers Dimopoulou I, Alsolaiman MM S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Lindner H. [Limitations and hazards of percutaneous liver biopsy with the Menghini needle. Experiences with 80,000 liver biopsies]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1967;92:1751-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McGill DB, Rakela J, Zinsmeister AR, Ott BJ. A 21-year experience with major hemorrhage after percutaneous liver biopsy. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1396-1400. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Piccinino F, Sagnelli E, Pasquale G, Giusti G. Complications following percutaneous liver biopsy. A multicentre retrospective study on 68,276 biopsies. J Hepatol. 1986;2:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 804] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | LoIudice T, Buhac I, Balint J. Septicemia as a complication of percutaneous liver biopsy. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:949-951. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Jones EA, Sherlock S, Crowley N. Bacteraemia in association with hepatocellular and hepatobiliary disease. Postgrad Med J. 1967;43:7-4311. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Le Frock JL, Ellis CA, Turchik JB, Zawacki JK, Weinstein L. Transient bacteremia associated with percutaneous liver biopsy. J Infect Dis. 1975;131 Suppl:S104-S107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McCloskey RV, Gold M, Weser E. Bacteremia after liver biopsy. Arch Intern Med. 1973;132:213-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Morris JS, Gallo GA, Scheuer PJ, Sherlock S. Percutaneous liver biopsy in patients with large bile duct obstruction. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:750-754. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Murray HW, Dugowson CE. Liver biopsy septicemia. Gastroenterology. 1977;73:629-630. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Navarro A, Diaz-Curiel M, Castrillo JM. Guided liver biopsy septicemia. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:639-640. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Bubak ME, Porayko MK, Krom RA, Wiesner RH. Complications of liver biopsy in liver transplant patients: increased sepsis associated with choledochojejunostomy. Hepatology. 1991;14:1063-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Galati JS, Monsour HP, Donovan JP, Zetterman RK, Schafer DF, Langnas AN, Shaw BW, Sorrell MF. The nature of complications following liver biopsy in transplant patients with Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy. Hepatology. 1994;20:651-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |