Copyright

©The Author(s) 2023.

World J Clin Cases. Sep 6, 2023; 11(25): 6005-6011

Published online Sep 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i25.6005

Published online Sep 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i25.6005

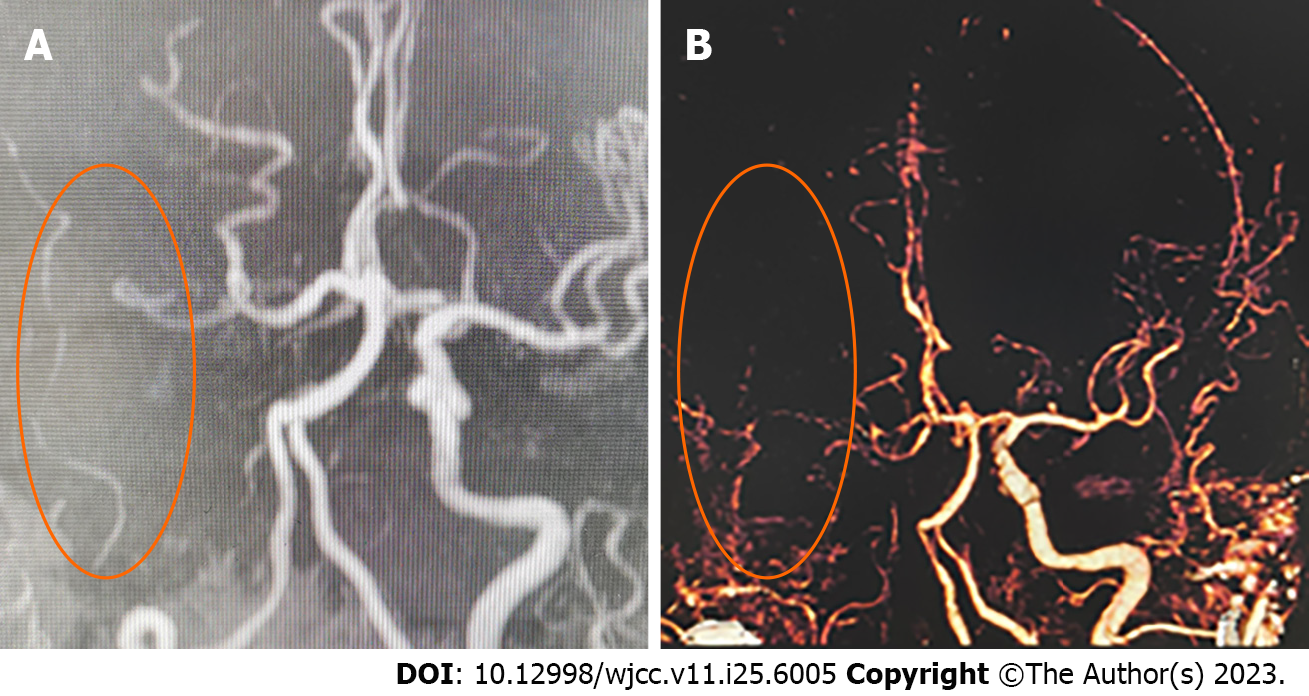

Figure 1 Image of an intracranial major artery embolism.

A and B: Magnetic resonance angiography and computed tomography angiography showing occlusion of the right internal carotid artery and middle cerebral artery (ellipses), respectively.

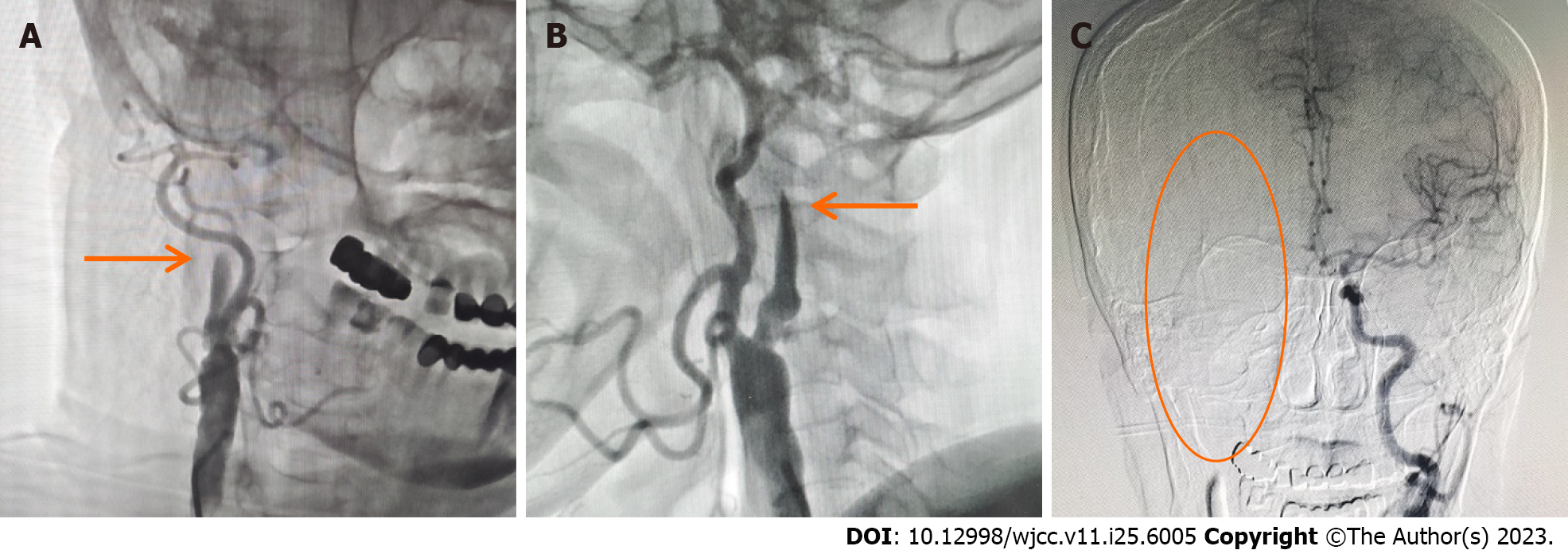

Figure 2 Angiography before thrombectomy.

A and B: Digital subtraction angiography showing an occlusion beyond the origin of the right internal carotid artery (arrows); C: The A1 segment of the right anterior cerebral artery was blocked, and there was no compensatory blood flow to the right middle cerebral artery (ellipse).

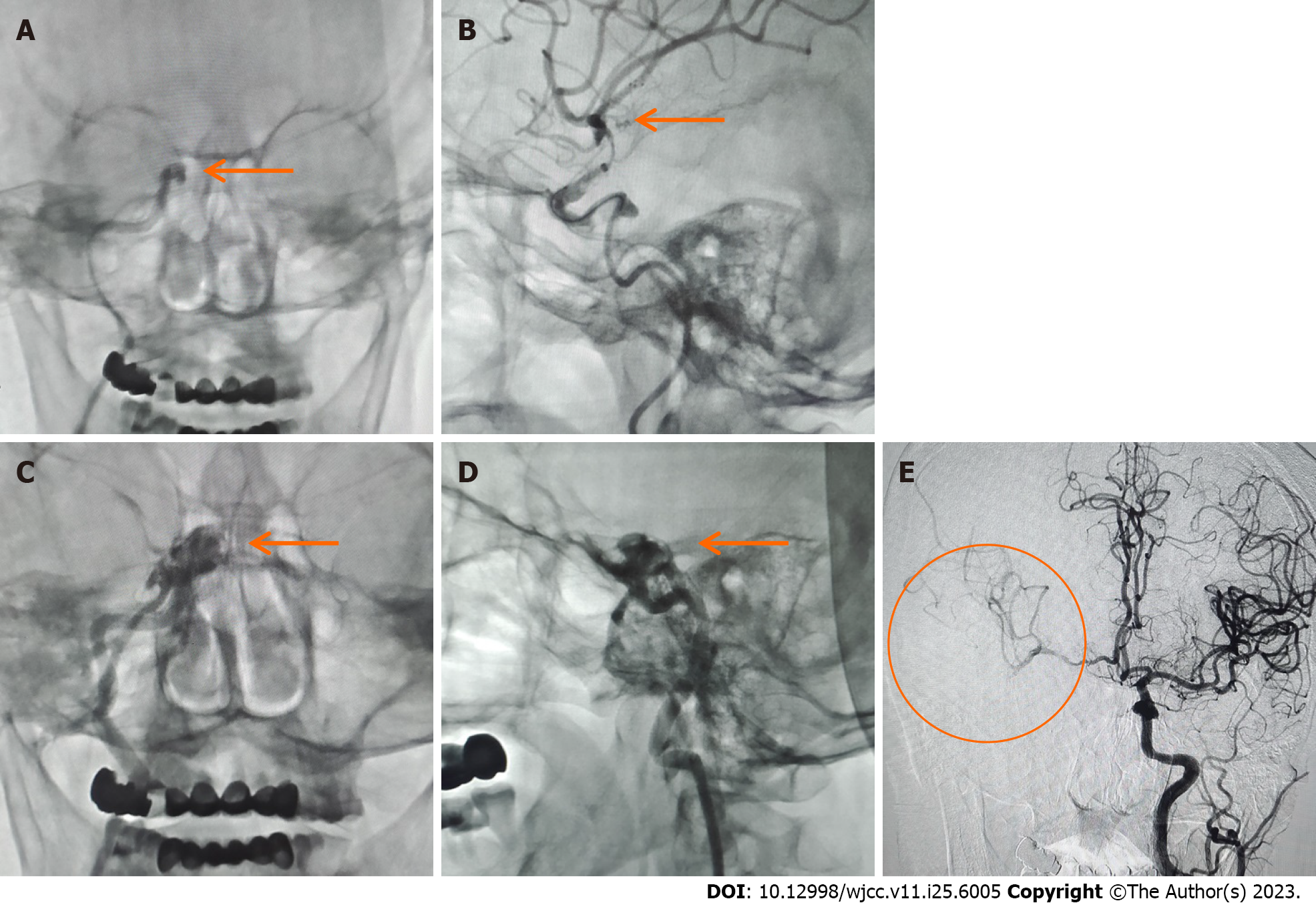

Figure 3 Thrombectomy and carotid-cavernous fistula formation.

A: After the aspiration thrombectomy, the digital subtraction angiography showed occlusion of the terminal bifurcation of the right internal carotid artery (arrow); B: After the first stent removal, angiography showed poor right middle cerebral artery (MCA) reflow and no carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF) (arrow); C and D: After a second stent thrombectomy, reexamination showed CCF (arrows); E: Reflow of the A1 segment of the right anterior cerebral artery to supply blood to the right MCA supply area (circle).

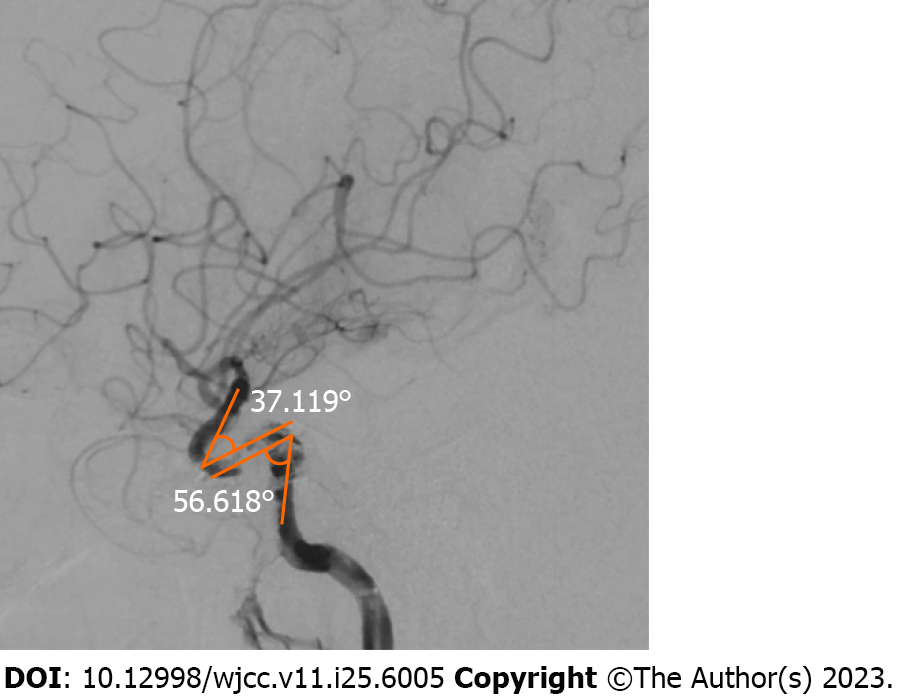

Figure 4 Cavernous internal carotid artery tortuosity.

The acute angle of the anterior genu = 37.119°, the posterior genu angle = 56.618°.

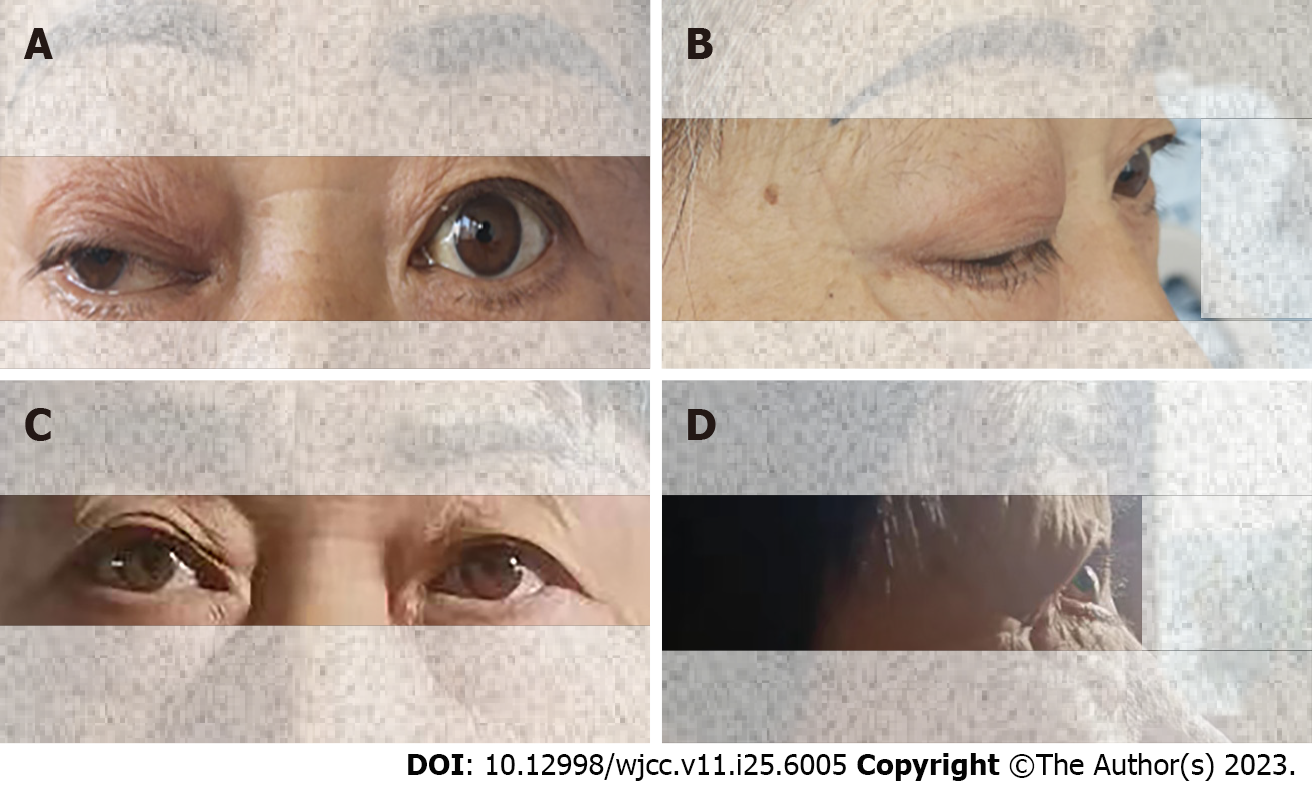

Figure 5 Comparison of the physical characteristics of the patient before and after carotid-cavernous fistula embolization.

A and B: Physical examination on admission: Right proptosis, ptosis and limited eye movement; C and D: After five months of follow-up, the symptoms were relieved.

- Citation: Qu LZ, Dong GH, Zhu EB, Lin MQ, Liu GL, Guan HJ. Carotid-cavernous fistula following mechanical thrombectomy of the tortuous internal carotid artery: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(25): 6005-6011

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i25/6005.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i25.6005