Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.98132

Revised: October 7, 2024

Accepted: December 18, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 260 Days and 19.8 Hours

Cognitive impairment is a major cause of disability in patients who have suffered from a stroke, and cognitive rehabilitation interventions show promise for im

To examine the effectiveness of virtual reality (VR) and non-VR (NVR) cognitive rehabilitation techniques for improving memory in patients after stroke.

An extensive and thorough search was executed across five pertinent electronic databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; MEDLINE (PubMed); Scopus; ProQuest Central; and Google Scholar. This systematic review was conducted following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guideline. Studies that recruited participants who experienced a stroke, utilized cognitive rehabilitation interventions, and published in the last 10 years were included in the review.

Thirty studies met the inclusion criteria. VR interventions significantly improved memory and cognitive function (mean difference: 4.2 ± 1.3, P < 0.05), whereas NVR (including cognitive training, music, and exercise) moderately improved memory. Compared with traditional methods, technology-driven VR approaches were particularly beneficial for enhancing daily cognitive tasks.

VR and NVR reality interventions are beneficial for post-stroke cognitive recovery, with VR providing enhanced immersive experiences. Both approaches hold transformative potential for post-stroke rehabilitation.

Core Tip: Virtual reality (VR) and non-VR cognitive rehabilitation interventions show promise in enhancing memory and overall cognitive function in patients who experienced a stroke. In this systematic review of 30 studies, VR-based ap

- Citation: Mathew R, Sapru K, Gandhi DN, Surve TAN, Pande D, Parikh A, Sharma RB, Kaur R, Hasibuzzaman MA. Impact of cognitive rehabilitation interventions on memory improvement in patients after stroke: A systematic review. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 98132

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/98132.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.98132

Cerebrovascular accidents or strokes are major causes of morbidity worldwide and impose a substantial burden on individuals, families, and healthcare systems[1]. Stroke is among the primary contributors to mortality and disability worldwide[2,3]. Cognitive impairment following a stroke is the most prevalent type of disability[4]. In the realm of neurological rehabilitation, the aftermath of a stroke presents a formidable challenge, necessitating comprehensive strategies to mitigate the multifaceted impact on an individual’s physical, psychological, and cognitive well-being[5]. While considerable progress has been made in the acute management of stroke, the consequences of stroke-related cognitive impairments continue to delude both clinicians and researchers[6]. Cognitive deficits, including memory loss, attention difficulties, and executive dysfunction, often persist in patients who experienced a stroke, with some studies suggesting that the rate of dementia is approximately 30% at 1-year post-stroke. As the population continues to age and stroke incidence remains a significant global health issue, the imperative to optimize recovery strategies has never been more pronounced[1,7].

Cognitive rehabilitation, a therapeutic approach aimed at improving cognitive functioning and daily living skills through structured interventions, has emerged as a promising avenue to address these enduring challenges[8,9]. This is a dynamic and evolving field and has emerged as a beacon of hope for individuals who experienced a stroke and are grappling with memory impairments[10]. The principal goals of post-stroke cognitive rehabilitation are to improve cognitive functioning to allow individuals to participate in everyday activities on their own, reduce the severity and impact of impairment, and improve overall quality of life. These requirements can change as patients progress, receive support from caregivers, or move through various stages of recovery following a stroke[11].

The efficacy of various cognitive rehabilitation interventions in post-stroke recovery has garnered increasing attention in the last few decades. This systematic review aimed to comprehensively evaluate the existing body of evidence to shed light on the benefits and limitations of cognitive rehabilitation interventions for patients who experienced a stroke in terms of memory improvement. Several factors explain the rationale for undertaking this review. First, stroke survivors frequently experience cognitive deficits. Personalized rehabilitation strategies are needed since these impairments can impact a variety of cognitive areas, including memory, attention, language, executive function, and visuospatial abilities[12]. Second, the diversity of available cognitive rehabilitation techniques and interventions complicates the decision-making process for clinicians and rehabilitation specialists. A rigorous evaluation of the literature is needed to guide evidence-based clinical practice.

Stroke-induced memory impairment can range from mild forgetfulness to severe amnesia, impacting not only individuals but also their caregivers and the broader healthcare system[13]. Understanding the potential benefits of cognitive rehabilitation interventions for memory improvement is pivotal, as it may pave the way for more tailored and effective post-stroke rehabilitation strategies[11]. Recent technological advancements have led to the development of innovative rehabilitation programs, such as computer-based cognitive training and virtual reality (VR) simulations, which offer interactive and engaging environments for patients[14]. These modern approaches stand in contrast to traditional methods that often involve paper-and-pencil exercises or therapist-guided recall and memory drills. While traditional methods are generally more accessible and cost-effective, they may lack the adaptability and immersive engagement provided by computer-based and VR programs[15]. Conversely, modern approaches can offer more personalized and data-driven experiences, potentially enhancing patient motivation and participation. However, they may be limited by accessibility issues and higher costs, particularly in resource-limited settings[16]. Evaluating the effectiveness of these modern approaches compared with traditional methods was critical to this review.

In this comprehensive analysis, we scrutinized the existing body of research to explore the outcomes of cognitive rehabilitation programs specifically designed to target memory deficits in patients who experienced stroke. By critically assessing the available evidence, we provided clinicians, researchers, and caregivers with valuable insights into the effectiveness of these interventions. Ultimately, this systematic review aimed to provide valuable insights into optimizing post-stroke cognitive rehabilitation strategies, contributing to improved patient outcomes and better quality of life for individuals affected by stroke-related cognitive dysfunction.

What is the impact of cognitive rehabilitation interventions, including memory training, neurorehabilitation, mind

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement was followed in the conduct and reporting of this systematic review[17]. This protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42023454330) in August 2023.

An extensive and thorough search was executed across pertinent electronic databases, such as the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE (PubMed), Scopus, ProQuest Central, and Google Scholar, to identify additional relevant studies. The gray literature and references of the included studies were also searched. The search method combined keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) terms relevant to the “population, intervention, control, and outcome” components of patients who experienced stroke, cognitive interventions, and memory impro

The search strategy was based on subject-specific header indices within each database, incorporating MeSH terms as well as their corresponding synonyms (keywords). Truncations, wildcards, and additional terms were selected to accurately represent the focus of the review. The Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were used to combine these search terms. The search strategy, which combined MeSH terms and keywords for MEDLINE (PubMed), is outlined in Table 1 and was adapted to adhere to the specific syntax requirements of each database.

| Search terms for MEDLINE database | ||

| P (population) | Patients who experienced stroke | “Post-stroke patients” OR “Stroke survivors” OR “Cerebrovascular accident patients” OR “Post-cerebrovascular accident individuals” OR “Patients with post-stroke sequelae” OR “Rehabilitated stroke patients” OR “Stroke recovery” OR “Post-stroke rehabilitation” OR “CVA survivors” OR “Hemiplegic patients post-stroke” |

| I (intervention) | Cognitive rehabilitation | “Cognitive rehabilitation” OR “Cognitive training” OR “Neurorehabilitation” OR “Cognitive therapy” OR “Cognitive retraining” OR “Cognitive intervention” OR “Brain injury rehabilitation” OR “Stroke rehabilitation” OR “Neuropsychological rehabilitation” OR “Memory rehabilitation” OR “Cognitive skill training” |

| O (outcome) | Memory improvement | “Memory enhancement” OR “Improving memory” OR “Memory boost” OR “Enhanced cognitive function” OR “Cognitive improvement” OR “Memory recovery” OR “Memory rehabilitation” OR “Memory training” OR “Cognitive enhancement” OR “Cognitive training for memory” |

| Sets “1-3” will be combined with ‘AND’ | ||

Two reviewers individually searched all titles and abstracts for studies that were pertinent to the review. The full texts of all relevant papers were retrieved and examined by the same reviewers, with conflicts resolved by consensus. Another author was assigned as the third reviewer to resolve any unresolved differences. The entire list of articles retrieved was imported into Rayyan software to remove duplicates and scrutinize the title and abstract.

The specific inclusion criteria were as follows: Studies involving patients who experienced a stroke as the target population; studies focusing on cognitive rehabilitation interventions, including memory training, neurorehabilitation, mindfulness, and VR; studies assessing memory improvement as an outcome measure; randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental, and observational studies; and studies published in English and those published within the last 10 years.

The exclusion criteria were studies not involving patients who experienced a stroke; studies focusing solely on non-cognitive interventions (e.g., physical rehabilitation); studies without a clear focus on memory improvement; studies without relevant outcome measures or lacking proper methodology; studies not available in the English language; and studies published before 2014.

The reviewers independently retrieved the following data and compiled it into a standard data extraction form: Study author; year; country; study purpose; setting; study design; participant characteristics; sample size; data collection method; type of cognitive rehabilitation; interventions; and significant results reported.

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The randomized trials were specifically evaluated for bias via version 2 of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment[18]. The risk of bias tool for nonrandomized studies of interventions was used to evaluate quasi-experimental and nonrandomized trials[19]. The methodological quality of this systematic review was appraised using the AMSTAR 2 tool, ensuring adherence to established guidelines for rigor and transparency in systematic review reporting (Supplementary material).

The data were systematically extracted from each included study and collated in tabular form (Table 2). This included details on study characteristics (e.g., author, publication year, study design), participant demographics (inclusion criteria), intervention specifics (e.g., type of cognitive rehabilitation, duration), and outcome measures related to memory improvement in patients who experienced a stroke. The review provided a narrative synthesis of the data extracted from the included studies, organized under several key headings. This offered a comprehensive understanding of the patterns, trends, and variations in the research findings, shedding light on the impact of cognitive rehabilitation interventions on memory improvement in patients who experienced a stroke.

| Ref. | Country | Aim of the study | Study design | Participant characteristics, sample size | Data collection method | Interventions characteristics | Key finding reported by author(s) |

| Wilson et al[32], 2021 | Australia | To test whether the intensive use of a home-based virtual rehabilitation system can improve cognitive and functional outcomes in patients recovering from stroke | Parallel randomized control trial | The patients who met the following inclusion criteria were included in the study: Those who had upper-limb weakness due to a confirmed unilateral stroke; expressed the intention to undergo rehabilitation; English speakers who could sit and maintain posture unassisted and possessed at least a minimal upper limb movement range as assessed by an occupational therapist. Excluded were patients with prior neurological disorders (except stroke); psychiatric or developmental disorders; visual impairments preventing task completion; and those under 18 years of age. n = 19 | Box and Block test. 9-Hole Peg Test. MoCA. SIS. Neurobehavioral function inventory | Patients who experienced a stroke received EDNA training at home for 30-min sessions, with a minimum of three and a maximum of four sessions each week over 8 weeks. The training included four goal-based and three exploratory movement tasks involving handheld objects or tangible user interfaces on a tablet. The control group engaged in 30-min sessions of a GRASP program for 8 weeks. In addition to conventional rehabilitation therapy, they participated in arm and hand exercises | Cognitive outcomes showed significant differences pretest and post-test for the EDNA group. The magnitude in MoCA improvement was moderate to large with the effect size g = 0.70 (t = 2.31, P = 0.036) |

| Jaywant et al[35], 2023 | New York | To elucidate the formulation of a combined executive function intervention in patients experiencing chronic stroke that integrated CCT with MST | Non-randomized pilot study | Inclusion criteria were first-time stroke more than 6 months before enrollment, English speakers, having an evidence of cognitive difficulties, willingness to participate for the full study duration, proficiency with a computer keyboard and mouse, not concurrently receiving other cognitive rehabilitation services and able to perform basic self-care functions. Patients with other neurological disorders, severe mental illness, alcohol/substance use disorder, severe depression requiring psychiatric care, dementia, or dependence in self-care activities due to cognitive deficits were not included. n = 3 | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8. Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire. WAIS. WMS. Symbol-Digit Modalities Test. TMT A and B. Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. WCPA | An intervention was developed that integrated CCT and MST to target executive functions and train for the transfer to daily C-IADLs. Rehacom was chosen as the software for CCT. The multicontext approach was used for the MST component | Participant P1 self-reported a slight improvement in everyday executive functioning on the BRIEF but demonstrated a slight decline in performance on neuropsychological measures and slightly worse performance on the WCPA. Participants P2 and P3 both demonstrated an improvement in select neuropsychological tests and the WCPA |

| Jung et al[36], 2021 | South Korea | To determine the efficacy of computer-assisted rehabilitation techniques in patients of stroke and TBI and to compare the patterns of cognitive function recovery in both these groups | Retrospective cohort study | 32 patients who were diagnosed with stroke or TBI using CT and magnetic resonance imaging and those patients with impaired cognition (MMSE score of ≤ 27) were enrolled. Patients with the presence of a previous central nervous system lesion, such as TBI, stroke, brain tumor, and epilepsy, an impossible one-step obey command due to higher brain dysfunction (aphasia or hemispatial neglect), poor cooperation, the presence of a visual or hearing impairment that interfered with cognitive rehabilitation, and unstable vital signs were excluded from the study | Computerized neuropsychological test. MMSE. MBI | Participants underwent 30 sessions of computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation (Comcog) five times a week. Comcog system uses 10 training activities: 2 auditory processing tasks that assess response time during auditory stimulation; 2 visual processing tasks that assess response time during visual stimulation; 2 selective attention tasks that track attention in distraction; 3 working memory tasks that assess recognition and recall memory using visual, auditory, and multisensory stimulation; and 1 emotional attention task that assesses responses to pleasant or unpleasant stimulation | A significant improvement was observed in MMSE (P = 0.000), MBI (P = 0.000), intelligence quotient (P = 0.002), and all computerized neuropsychological test components except for the word color test in the stroke group. When comparing the TBI and stroke groups, it was noted that all parameters, except for digit span forward, visual learning, word color test, and MMSE, had higher mean values in the stroke group. Significantly higher values were seen in the stroke group for visual span forward and card sorting test |

| Kober et al[37], 2015 | Austria | To evaluate an adaptive human-computer interface in improving cognitive function in patients who experienced a stroke | Non-randomized prospective study | 24 patients who experienced first-time stroke with any site of brain lesion and motor deficit were included in the study. Patients with visual hemi-neglect, dementia, psychiatric disorders such as depression or anxiety, other concomitant neurological disorders, aphasia, or insufficient motivation and cooperation were excluded from the study | Long-term memory was tested using CVLT and Visual and Verbal Memory Test 2. Short-term memory was tested using Corsi Block Tapping Test, Digit span test, CVLT, VVM2. Working memory was tested using Corsi Block Tapping Test backwards task and digit span test | For both NF training protocols, electroencephalography signal was recorded using a 10-channel amplifier with a sampling frequency of 256 Hz. Up to ten NF training sessions were carried out on different days three to five times per week. Each session lasted approximately 45 min and consisted of seven runs of 3 min each | After NF training, the sensorimotor rhythm patient group showed significant performance improvements in parameters of the CVLT assessing verbal short-term and long-term memory compared to the pre-assessment. Sensorimotor rhythm patients showed a numerical performance improvement in visual-spatial short-term memory |

| Li et al[38], 2022 | China | To determine if left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex iTBS can improve cognitive function in patients who experienced a stroke | Prospective single center randomized pseudocontrolled trial with double blinding | 58 patients who met the inclusion criteria in which stroke was confirmed by CT or magnetic resonance imaging, 18 to 65-year-old patients, post stroke cognitive impairment diagnosis, absence of visual or hearing impairment, ability to complete the assessment and training, vitally stable and have signed informed consent for iTBS treatment were included. Patients with cognitive dysfunction caused by craniocerebral trauma or neurological diseases, aphasia, unstable arrhythmias, or other serious physical conditions, contraindications of magnetic stimulation, history of seizures, patients in critical condition were excluded from the study | MMSE. Oxford cognitive screen. Event-related potential P300 pre and post intervention | Stimulation was done by using a transcranial magnetic stimulator (nagneuro 60 type stimulator) and a figure-of-eight coil. In the iTBS group, three continuous pulses at 50 Hz were repeated at 5 Hz (2 s on, 8 s off) for a total of 192 s and 600 pulses. In the sham stimulation group, coil was rotated by 90° so it sat perpendicular to the target area, and the minimum stimulation was generated. Stimulation parameters and site matched those of the iTBS group | Post-intervention MMSE scores showed a statistically significant increase from the baseline. After iTBS intervention, there was significant improvement in the overall cognitive function, executive function, and memory function |

| Haire et al[42], 2021 | Canada | To assess the outcome of TIMP interventions on improvement of cognitive and affective outcomes relative to baseline in patients who experienced a stroke | Randomized controlled trial | 30 participants who were chronic post-stroke and community-dwelling were randomized to one of three experimental groups who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Hemiparesis/unilateral stroke sustained more than 6 months prior to enrollment in the study; (2) Presence of at least minimal movement of the affected limb; (3) Age: 30-79 years; and (4) Ability to understand and follow simple instructions. Those patients who had a presence of comorbid neurological disorder and were actively participating in an upper extremity rehabilitation program at the same time as the study period were excluded from the study | TMT-part B. The forward DST. The General Self-Efficacy Scale. The Multiple Affect Adjective Check List-Revised. The Self-Assessment Manikin | The interventions used differed among the groups of participants: Group 1: 45 min of active TIMP training. Group 2: 30 min of TIMP followed by 15 min of cued motor imagery, involving listening to a metronome beat set for each exercise while engaging in motor imagery. Group 3: 30 min of TIMP followed by 15 min of motor imagery without external cues. Exercises focused on training of gross and fine motor control using acoustic and electronic instruments, which were selected and positioned to meet individual needs | TIMP + motor imagery seemed to improve cognitive adaptability in individuals with chronic post-stroke conditions, potentially attributable to the reinforcement of mental constructs via motor imagery after engaged training |

| Abd-Elaziz et al[47], 2015 | Egypt | To measure the effect of cognitive rehabilitation of elderly patients with a history of stroke on their cognitive function and ADL | Quasi experimental research design | 70 elderly patients who were aged 60 years and above with post stroke dementia with a history of stroke at least three months prior to study documented by CT or magnetic resonance imaging brain and with a stable medical status were recruited for the study. Patients with the presence of additional severe medical conditions preventing active rehabilitation, aphasia, agnosia, disturbed conscious level and those on antipsychotic drugs, antiepileptic, and anticoagulant drugs were excluded from the study | MMSE: Including five items (orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and language. Digit span (forward and backward). Logical memory. Geriatric Depression Scale. Barthel index | The program consisted of three theoretical session about health education for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and prevention of recurrent stroke and five practical sessions about spatial memory, attention and concentration, visual attention, fish face task, N400 task | Training programs significantly benefited cognitive function in elderly patients who experienced a stroke. Significant differences were observed in pretest, post-test, and follow-up assessments in the studied group, including MMSE, logical memory, digit span forward, and digit span backward (P value = 0.000). At baseline, group I had a mean logical memory of 4.65 ± 2.37, and group II had 4.37 ± 1.92. After the program, group I showed slight improvement, with a mean of 6.62 ± 2.12 |

| Hellgren et al[28], 2015 | Sweden | Aimed at investigating the effects of computerized working motor training on working motor skills, cognitive tests, activity performance, and estimated health and whether the effects of computerized working motor training can be attributed to gender or time since injury | Randomized controlled trial- crossover design | Inclusion criteria: (1) Age between 20-65 years; (2) With subjective working motor impairment; (3) Significantly impaired WAIS WM index compared with index of verbal comprehension; and (4) Presence of motivation for training. Exclusion criteria: (1) Intelligence quotient ≤ 70 as measured with WAIS-III/WAIS-IV; (2) Depression; and (3) Perceptual or motor difficulties that make the computerized WM training impossible. n = 48 | Neuropsychological tests focused on verbal and visual working memory: Paced Auditory Serial Attention Test; forward and backward block repetition; and Listening Span Task. EQ-5D questionnaire and the interviews based on the Canadian occupational performance measure | The computerized WM training program Cogmed was used. It consisted of various visuospatial and verbal working memory tasks. The difficulty of each task was adapted to each patient’s WM capacity. After completing the 25 training sessions, each individual was assigned a WM index. Each session was 45-60 min of intense exercise including one break with the exercise intensity varying between 4-5 days/week for 5-7 weeks. All participants were trained in pairs or in groups of three, and both individual performances and group performances were analyzed and presented at a 20-week follow-up session | After the program ended 20 weeks later, the group showed significant improvements on all neuropsychological tests (P < 0.001). There was a marked positive change in the working memory index (P < 0.001), with each patient showing improvement during the training. Computerized working memory training can enhance cognitive abilities and daily life performance for those with acquired brain injuries, particularly when started early in rehabilitation |

| Fishman et al[48], 2021 | Canada | To determine whether a simple intervention targeting goal setting could improve cognitive performance across commonly affected domains (attention/working memory, and verbal memory) in the chronic phase of stroke | Randomized controlled trial-single-blind, parallel-design | 72 stroke survivors were randomly assigned to experimental and control group who met the inclusion criteria such as English speaking, nonaphasic individuals between 35 and 90 years of age with definite ischemic stroke diagnoses based on CT and magnetic resonance imaging scans at least 3 months post stroke. Participants with severe aphasia or dementia were excluded from the study | Controlled Oral Word Association Test. CVLT-II. Semantic fluency test. DST. TMT. Verbal fluency tasks | For each task, half of the participants were asked to establish a goal to increase their performance by 20%; the researcher gave them a specific number to aim for. CVLT encouraged participants to set goals for their word learning task. If they successfully recalled at least 10 words, they were to recall 1 extra word; if they correctly recalled fewer than 10 words, they were to recollect 2 additional words | Goal setting improved cognitive performance in stroke survivors. Participants with goal-setting instructions showed better executive function, attention/working memory, and learning compared to those with standard instructions. They exceled in tasks involving verbal executive function, attention/working memory, and verbal learning |

| Fernandez-Gonzalo et al[21], 2016 | Sweden | To validate the effectiveness of resistance exercise in individuals with greater physical capabilities, focusing on various cognitive functions such as working memory, verbal fluency tasks and attention | Pilot randomized controlled trial | Participants who were included in the study were individuals who had experienced a stroke, over 40 years of age, at least 6 months post-stroke, had mild to moderate hemiparetic gait, and could perform closed-chain exercises with the prescribed device. Exclusion criteria included unstable angina, congestive heart failure, severe arterial disease, major depression, dementia (scoring < 24 on the MMSE), difficulty understanding instructions, or chronic pain. n = 32 | Digit span forward. Spatial span forward - WMS-III. Conners Continuous Performance Test-II. Stroop Color and Word Test. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test. Verbal fluency test. Semantic fluency | Participants underwent unilateral resistance exercise training using the more-affected leg on a flywheel leg press. This training occurred 2 days per week, with over 48 h of rest between sessions, for a period of 12 weeks. The training sessions consisted of a standardized warm-up, followed by 4 sets of 7 maximal repetitions designed to induce ECC overload as validated in previous stroke studies. The training involved pushing with maximal effort during the entire range of motion in the concentric phase, resisting inertial force during the first part of the eccentric phase, and applying maximal effort to stop movement at about 70° knee flexion | The training group showed enhancements in cognitive function. This included improved verbal fluency and executive functions, as measured by the verbal fluency test and TMT |

| Faria et al[22], 2016 | Portugal | To check the effectiveness and benefits of virtual reality-based cognitive rehabilitation through simulated ADL via Reh@City | Randomized controlled trial | Patients who experienced a stroke were randomly assigned to intervention and control group. Inclusion criteria: MMSE > 15; ability to read and write; capacity to sit; no hemi-spatial neglect; and motivation to engage in the study. Patients with moderate or severe language comprehension deficits were excluded | Addenbrooke cognitive examination, attention, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuo-spatial abilities. TMT A and B. Picture arrangement test. SIS 30. System Usability Scale | Virtual reality-based cognitive intervention used a city simulation called Reh@City, which featured a three-dimensional environment with streets, sidewalks, buildings, parks, and moving cars. Reh@City required patients to complete common daily tasks at four frequently visited locations: A supermarket; a post office; a bank; and a pharmacy. The system offered visual feedback with time and point counters, rewarding patients for completing objectives and intermediate tasks while deducting points for mistakes or using the help button. This mainly targeted executive functions, encouraging problem-solving, planning, and reasoning skills | The study revealed that the virtual reality-based cognitive rehabilitation had a significantly positive impact on cognitive functions like global cognitive performance, attention, memory, visuospatial skills, and executive functions. It also led to enhancements in subjective health status, physical functioning, and overall recovery. These results indicated that the virtual reality-based cognitive rehabilitation intervention had a positive effect on cognitive and functional outcomes for patients who experienced a stroke. Notably, memory within the experimental group saw significant improvement (Z = -2.081, P = 0.037, r = 0.69) |

| Faria et al[23], 2020 | Portugal | To compare the effectiveness of two cognitive rehabilitation interventions in improving cognitive function and self-perceived cognitive deficits in patients experiencing chronic stroke | Randomized controlled trial | Participants who were included in the study were those under 75 years, in 6 months post-stroke chronic phase, with no hemi-spatial neglect, ability to sit, and motivated to take part in the study. Patients whose MoCA scores fell more than two standard deviations below the average score, with severe depressive symptoms, and those who had received occupational therapy within the 2 months leading up to the study were not included | Neuropsychological assessment. MoCA. TMT A and B. Verbal paired associates from the WMS-III-memory assessment. Digit span (forward and backward recall conditions). Symbol search. Digit symbol coding. Patient-Reported Evaluation of Cognitive State | The task generator is a tool for creating personalized cognitive rehabilitation programs consisting of 11 tasks. After assessing each participant’s cognitive abilities using the MoCA, a training program was generated. The virtual reality-based Reh@City v2.0 intervention took the same task generator tasks and placed them in a virtual city. Patients had to complete cognitive tasks related to everyday activities like shopping or reading the newspaper. This virtual city included billboards and products from real places in Portugal to make the tasks relatable to the real world | The task generator intervention enhanced orientation on the MoCA, along with specific processing speed and verbal memory. The task generator group only showed significant improvements in retention scores, both immediately after the intervention and at follow-up. In the learning and memory test, the Reh@City v2.0 group significantly improved retention and recognition scores after the intervention. Reh@City v2.0 performed better in general cognitive function, visuospatial ability, and executive functions and showed significant and substantial improvements in verbal memory and processing speed |

| Liu et al[24], 2022 | China | To evaluate the effectiveness of an immersive virtual reality puzzle game as a rehabilitation therapy for elderly patients who experienced a stroke with cognitive issues with primary focus is on enhancing executive function and visual-spatial attention | Pilot randomized controlled trial | 30 elderly patients with post-stroke cognitive impairment in the age group between 60 and 90 years old, having MoCA score between 18 and 26, Fugl-Meyer motor scale exceeding 85 for at least one upper and lower limb. Patients who were challenging to evaluate, examine, or could not follow instructions and with severe hearing or visual impairment, mental disorders, or a history of epilepsy or vertigo were excluded from the study | MoCA scale. TMT-A. Digit symbol substitution test. DST-forward and DST-backward. Verbal fluency test. MBI | The control group underwent traditional cognitive training, which included activities such as processing speed and attention training, memory training, computational ability training, and problem-solving ability training. The intervention group used an immersive virtual reality system for training, which included life skills training, exergames, and entertaining games, totaling 16 different games. Both groups received an extra 15 min of intervention each day, 6 days a week, for 6 weeks. Cognitive function was evaluated before and after the 6-week treatment for all participants. Self-report questionnaires were given only to the IVRG group after 6 weeks of training | Virtual reality-based puzzle games can enhance cognitive function in elderly patients who experienced a stroke, including overall cognition, memory, attention, and daily living skills. Significant improvements were observed memory improvement in patients who experienced a stroke and underwent immersive virtual reality-based training forward DST (Z = 0.78, P = 0.435 > 0.05) backward DST (Z = 0.347, P = 0.728 > 0.05) |

| Maier et al[20], 2020 | Spain | To assess if adaptive conjunctive cognitive training in patients experiencing chronic stroke improved attention, memory, spatial awareness, and depressive mood compared to standard cognitive tasks, while considering comorbidities | Randomized controlled pilot trial | 30 patients experiencing chronic stroke were randomized into control and intervention group who were in the age group of 45 to 75 years, had a cognitive impairment, and absence of severe upper limb motor disability. Patients with severe cognitive impairment and impairments like spasticity, communication disabilities, hemianopia, physical impairments, or severe mental health problems were excluded from the study | Averaged standardized composite scores. Neuropsychological test battery. Corsi Block Tapping Test Backward (Corsi B). RAVLT immediate. Delayed recall (RAVLT D). WAIS digit span backward (WAIS B) | The rehabilitation gaming system was used for daily cognitive training in a study where participants were split into an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group underwent a 6-week adaptive conjunctive cognitive training using the rehabilitation gaming system. The control group worked on standard cognitive tasks at home over the same 6-week period. Cognitive assessments, including executive function, spatial awareness, attention, and memory, were conducted at three points: Baseline, after 6 weeks, and during an 18-week follow-up | The experimental group demonstrated noteworthy enhancements in attention and spatial awareness, whereas the control group displayed memory improvement but not in other areas. Virtual reality-based cognitive training shows potential for patients who experienced a stroke, particularly those dealing with depression |

| Marangolo et al[41], 2018 | Italy | To investigate the effects of tDCS on language recovery in aphasic individuals | Randomized controlled trial- crossover, double-blind design | The study involved 12 participants (6 males and 6 females) with left-brain damage and chronic aphasia. Inclusion criteria were patients who were native Italian speakers, right-handed before their brain injury, had experienced a single left-hemispheric stroke at least 6 months prior, possessed mild affluent aphasia without articulatory difficulties, possessed basic comprehension skills, and had no attention or memory deficits that could affect their performance | Standardized language tests (the Battery for the Analysis of Aphasic Disorders test). Neuropsychological battery of tests-working memory | tDCS was applied over the right cerebellar cortex for 20 min. Each stimulation condition consisted of five consecutive daily sessions over 1 week with a 6-day gap between sessions. During the tDCS sessions, participants completed specific language tasks, such as naming pictures and generating verbs in response to presented nouns. In both tasks, the examiner manually documented the participant’s responses on a separate sheet. If the participant did not provide a response within the 20-s timeframe, the program automatically displayed the next picture or noun | The study suggested that cathodal cerebellar tDCS coupled with language training could improve verb retrieval in individuals with aphasia. Notably, the improvement was more pronounced in the cognitively demanding verb generation task. These findings indicated the potential therapeutic benefits of cerebellar stimulation for aphasia treatment, particularly in tasks involving executive and memory components |

| Oliveira et al[33], 2022 | Portugal | To evaluate a virtual reality-based approach for aiding cognitive recovery in patients who experienced a stroke | Single-arm pre-post design | 30 sub-acute patients who experienced a stroke over the age 18 with no impairments and history of psychiatric, neurological disorders or substance abuse, and having sufficient cognitive and language abilities and willing to participate. Those patients who could not complete at least 6 training sessions (i.e. 180 min of intervention) were excluded from the study | MoCA. Frontal assessment battery. WMS-I. Color Trails Test | The Systemic Lisbon Battery is a virtual reality program set in a city where patients engage in various activities such as brushing teeth, showering, selecting clothes, arranging shoes, following recipes, recalling news or shopping in a virtual shop. Each session incorporates spatial orientation and memory by recalling door numbers and street details. The intervention plan was structured by difficulty and targeted cognitive domains, with interactions using a computer mouse. For the completely dependent patients, the psychologist controlled the mouse based on patient instructions. Each patient completed 7 sessions, each lasting approximately 30 min | The results indicated superior performance in assessments of overall cognitive function, executive abilities, attention, and memory. Memory [WMS memory quotient: t(25) = -3.297; P < 0.01]. Modified reliable change index analysis indicated that 15% improved in memory. Virtual reality exercises focusing on everyday activities can offer short-term cognitive rehabilitation benefits for patients who experienced a stroke |

| Withiel et al[45], 2019 | Australia | To assess the effectiveness of group compensatory memory skills training and CCT in rehabilitating memory after stroke | Randomized controlled trial | 65 participants were randomized into two interventional and one waitlist control group. Those with a history of stroke confirmed by neurological examination and brain imaging at least 3 months previously were included in the study. Patients with physical impairment and with severe cognitive or communication deficits were excluded | The RAVLT -verbal and visual learning. Brief visuospatial memory test-revised–memory. Royal Prince Alfred Prospective Memory Test-prospective memory. Symbol Span Test-spatial memory. Digit span backward-verbal working memory. Everyday Memory Questionnaire-Revised. Part A of the Comprehensive Assessment of Prospective Memory | An adapted version of the manualized memory group program, “Making the Most of your Memory: An Everyday Memory Skills Program,” was used. It consisted of six 2-h sessions, conducted weekly at a university psychology training clinic. An experienced neuropsychologist led the sessions with two provisional psychologists’ assistance. LumosityTM, is an adaptable CCT program. The training regimen consisted of 30 min per day, 5 days a week, for 6 weeks. After the project concluded, participants on the waitlist were given the option to select a memory intervention | 65 community-dwelling stroke survivors took part (24 in the memory group, 22 in CCT, and 19 in the wait-list control). The memory group showed more significant progress in memory-related goals and internal strategy use at the 6-week follow-up compared to computerized training and wait-list control. Memory skills groups, rather than computerized training, may assist community-dwelling stroke survivors in reaching their functional memory goals |

| Park and Lee[29], 2018 | South Korea | To compare CMDT with AMST based on its effects on increasing attention, memory, and cognitive functioning when used in the rehabilitation of individuals with chronic stroke | Pilot randomized controlled trial | 30 participants were included in the study and randomly assigned to the experimental and control group who were diagnosed stroke with cerebral hemorrhage or cerebral infarction, MMSE-K score ≥ 21, able to follow verbal instructions and having dual task capability. Patients with dementia, history of seizure, high blood pressure or angina, and visual or auditory impairments that would interfere with task performance were excluded | TMT-A. TMT-B. ST. DST. CMDT and AMST of the experimental group using a metronome | The control group received three sessions of CMDT every week for 6 weeks and included motor tasks associated with balance and posture while sitting and standing, which were performed simultaneously with cognitive tasks related to attention, memory, and cognitive function. Tasks included counting backward from a number while sitting up and naming the days of the week in reverse order during trunk rotation. The interventional group received CMDT + AMST in a different room than the control group but in the same manner as the control group. AMST used the interactive metronome (IM pro 9.0) and involved various motor tasks. These tasks included tapping both hands while making a semi-circular movement and pressing the right or left trigger in response to the reference sound | In the interventional group, significant changes occurred in multiple test scores: TMT-A and TMT-B (P = 0.001), DST-forward and DST-backward (P = 0.001), ST-word, and ST-color (P = 0.001). Combined (CMDT + AMST) intervention was more effective in improving cognitive function, attention, and memory in patients with stroke than CMDT alone |

| Park and Park[30], 2015 | South Korea | To study the effects of CoTrans (computer-based cognitive rehabilitation program) on the cognitive function and visual perception of patients with acute stroke | Randomized controlled trial | 30 participants were included in the study and randomly assigned to the experimental or control group who had history of no more than one stroke with an onset duration of < 3 months; MMSE score of ≤ 23; has the ability to understand instructions and use the controller with the unaffected upper limb and not having unilateral hemispatial neglect and hemianopsia | Lowenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment. Motor-free Visual Perception Test-3 | The control group received conventional cognitive rehabilitation with emphasis on visual perception ability using pencil and paper. The experimental group received a Korean Computer-based cognitive rehabilitation program with CoTrans program using a joystick and a large button focusing on visual perception, attention, memory, orientation, sequencing, and categorization | Computer based cognitive rehabilitation with CoTrans may contribute toward the recovery of cognitive function and visual perception in patients with acute stroke. The improvement in Lowenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment and Motor-free Visual Perception Test was higher in the experimental group than in the control group subjects after 20 sessions. A statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups at the end of treatment |

| Patani[44], 2020 | India | To determine how neurobic exercises affect the memory of patient who experienced a stroke | Randomized controlled trial | The study included 40 participants aged 50 to 80, of both genders, diagnosed with stroke, MMSE score > 22, higher Brunnstrom’s recovery stage and Barthel index score > 12. Patients with neuromusculoskeletal condition, other psychiatric illness, hearing and visual deficit, hemodynamic instability with uncontrolled hypertension and other progressive metabolic diseases were excluded | MoCA scale. SIS | Neurobic exercises are a distinctive brain workout program that combines physical senses such as vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch, along with emotional senses in a regularly changing routine | The post-treatment mean MoCA score in the experimental group was 18.35 ± 4.36, in comparison, the conventional group had a mean MOCA score of 11.70 ± 3.31. With the use of SIS and MoCA, neurobic exercises significantly improved memory |

| Prokopenko et al[31], 2013 | Russia | To evaluate the effectiveness of novel computerized correction programs for cognitive neurorehabilitation | Randomized controlled trial | Inclusion criteria: Patients with cognitive problems following stroke; having mild dementia, without significant speech problems or epilepsy; and in the acute and early restorative period of stroke. Exclusion criteria: Patients with MMSE < 20; medically unstable; were not fluent in Russian or had speech problems. n = 43 participants (experimental group: 24 participants; Control group: 19 participants) | МоСА. Schulte’s tables (for attention deficit estimation) | The experimental group received training with computer programs 30 min/day for 2 weeks in addition to standard treatment. Visual and spatial memory training involves remembering the positions of images in a five-by-five square with an increasing number of objects (images of books). The patient clicks on the cells to recall the image positions. The number of objects to remember increases with correct performance until two mistakes are made. Information about speed and correctness of answers and the amount of information memorized is displayed on the screen. Other computerized tasks in the cognitive correction program include remembering symbol sequences, arranging clock hands, and serial counting | The intervention group displayed a noteworthy enhancement in cognitive function, as indicated by the MMSE, frontal assessment battery, clock drawing test, Schulte’s test, and MoCA (with a significance level of P < 0.01), following the treatment course |

| Song and Fu[59], 2022 | China | To investigate the impact of cognitive impairment rehabilitation on the cognitive performance of older patients who experienced a stroke | Retrospective study | 120 patients with the first onset of stroke, having stable vital signs were randomly assigned to the study and control group. Patients with complicated cerebrovascular conditions, cognitive impairment, physical limitations, intellectual abnormalities, malignant tumors were excluded | МоСА | The study group received additional rehabilitation for cognitive impairment. Patients with MoCA scores below 26 had enhanced cognitive training. This training included exercises for time, space, and character discrimination, where patients were shown familiar individuals, places, and the current time and asked to distinguish them independently. Number practice aimed to help patients understand basic numbers, sort and calculate them, enhancing logical thinking. Training for language and memory abilities involved increased communication with family members, memory stimulation, daily reading sessions, and exercises for reasoning abilities like describing and categorizing various daily items in the ward | The scores for the study group cognitive function, simple intelligence state, and neurological deficiency were higher than the scores of the control group following the rehabilitation treatment (P < 0.05) |

| Studer et al[34], 2021 | Germany | To examine if patients’ commitment to daily self-directed training could be improved through precommitment | Randomized controlled trial | 95 adult patients who experienced a stroke with visuospatial memory impairments were recruited and randomly allocated into three groups: A precommitment, control and standard therapy only group. Patients with moderate or severe aphasia, dementia, severe deficits in multiple cognitive domains, inability to provide consent and multi-resistant bacteria were excluded | Wechsler spatial span test. Verbal learning and memory test | Wizard (Peak) offers tablet-based training for visuospatial working memory. In the game, geometrical figures are hidden under cards. During each round, the cards are revealed one by one in a random order, and the player must select the correct hiding place using the touchscreen. The game has a narrative involving a Wizard who needs items like strength, weapons, and trophies to battle monsters. Tokens are earned through successful trials and lost when mistakes are made. The game adjusts its difficulty based on the player’s performance and is played on tablet computers in a designated room with technical support. After each training session, patients rated their enjoyment of the Wizard game on a Likert scale from 1 to 7 | Patients who conducted Wizard training showed a significantly larger pre-post change in the Wechsler spatial span test backward scores than those who were not offered [F(1,80) = 12.947, |

| Tsai et al[39], 2020 | Taiwan | To investigate the comparative effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and iTBS in patients with left hemispheric stroke on patients’ global, memory, attention, language and visuospatial cognitive function | Randomized, controlled, double-blind study | 44 patients were randomly assigned to rTMS, iTBS and sham groups diagnosed with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke with cognitive impairment, no history of seizure, intracranial occupying lesion, use of antidepressants or neurostimulators. Patients with unstable cardiac dysrhythmia, fever, infection, hyperglycemia, epilepsy or previous administration of tranquilizers, neurostimulators or other medication that significantly affected the cortical motor threshold and those with metallic intracranial devices, pacemakers or other electronic devices in their bodies were excluded | RBANS. Beck Depression Inventory | The iTBS treatment consisted of 3 pulses of 50 Hz bursts repeated at 5 Hz for a total of 190 seconds (600 pulses). The 5 Hz rTMS protocol was applied at an intensity of 80% of the resting motor threshold, with 2 strains at an interval of 8 seconds, repeated every 10 seconds for a total of 10 minutes (600 pulses). Each patient received 10 days of rTMS treatment, administered in the morning from Monday to Friday for 2 consecutive weeks. For the control group, a placebo coil (Magstim) for the sham stimulation was used, which delivered less than 5% of the magnetic output with an audible click on discharge | After 10 rTMS sessions, the 5 Hz rTMS group showed significant increases in total RBANS score (P = 0.003) and improved delayed memory (P = 0.007). The iTBS group exhibited significant increases in total RBANS score (P = 0.001) and enhancements in immediate memory (P = 0.006), language (P = 0.005), and delayed memory |

| Aben et al[25], 2014 | Netherlands | To ascertain how a novel MSE training program affects the MSE of patients who experienced a stroke, depression, and quality of life over the long run | Multicenter randomized controlled trial | 153 patients between the age group of 18 and 80 years, living independently, 18 months or more post onset after stroke and reported subjective memory complaints. Patients with progressive neurological disorders such as dementia or multiple sclerosis, alcohol or drug abuse, subdural hematomas, or subarachnoid hemorrhages | Metamemory in adult questionnaire | The MSE training, adapted for patients who experienced a stroke from a program by Verhey and Ponds, consisted of three main parts: An introduction about memory and stroke, training on internal and external memory strategies, and psychoeducation on how mood, anxiety, and memory-related worries affect memory complaints. It involved nine 1-h sessions conducted twice a week, including training booklets and homework assignments. The control group did not receive therapeutic interventions but was educated about stroke causes and consequences. They had nine 1-h sessions, similar to the MSE group, but did not receive homework assignments. A trained psychologist led both groups | MSE improved significantly over the intervention period in the experimental group compared with the control group (P = 0.010; Cohen’s d = 0.48). In younger patients in the experimental group, MSE improved significantly more than the MSE score in the control group (B = 0.56; P < 0.003) |

| Chiu et al[46], 2021 | Taiwan | To assess how a home-based reablement program impacts various rehabilitation outcomes in patients who experienced a stroke | Single-blind randomized clinical trial | 24 participants were randomly assigned to interventional and control group who were above the age of 20, having modified Rankin scale score of 2-4 points, and could maintain a sitting position for at least 30 min in a wheelchair or bed without any assistance, and have the ability to follow instructions and cooperate with the procedures. Patients with orthopedic disorder, progressive disease, and peripheral nerve injury were excluded | Fugl-Meyer Assessment for the upper extremity. SIS | The home-reablement group underwent goal-oriented training for ADLs for 50 min a day, once a week for 6 weeks. During the initial week, the occupational therapist leading the program focused on 2 to 3 ADLs that the participants considered important but challenging to perform. The therapist not responsible for the assessments gauged the participants’ desire for improvement and assessed their current abilities in carrying out these ADLs. From the second to the sixth week, the occupational therapist taught the participants how to perform these ADLs effectively and provided them with strategies like task analysis, task modification, and simplifying the work process | Individuals who had experienced a stroke showed the possibility of improving their motor function, ADL and instrumental ADL, emotional well-being, memory, and participation in various activities through their participation in a home-reablement program |

| Baylan et al[43], 2020 | United Kingdom | To evaluate the viability and approval of integrating short mindfulness training into a music listening program for individuals recovering from a stroke | Randomized clinical trial | English-speaking adults who are native speakers, aged 18 to 80 years during the first 11 months of recruitment, and in the acute stage after being clinically and/or radiologically diagnosed with an ischemic stroke are included in this study. Patients with comorbid progressive neurological or neurodegenerative condition, major psychiatric disorder, history of major substance abuse problems, clinically unstable, unable to give informed consent or unable to cooperate are excluded. N = 72 were recruited and randomly allocated into mindful music listening (n = 23), music listening alone | MoCA. Test of Everyday Attention. BIRT Memory and Information Processing Battery. WAIS. WMS. Controlled Oral Word Association Test | Participants got an iPod Nano and were told to listen to their selected material daily for at least an hour, aiming for a total of 56 h over the 8 weeks and were instructed to keep a daily written record of their listening to measure adherence. In the mindful-music group, they received a recording with a brief mindfulness exercise to complete daily before listening to music for the first three weeks. These were short exercises focused on mindfulness elements. Participants were guided to let thoughts pass and refocus if distracted. At the fourth visit, another brief exercise (following the breath) was introduced for the next three weeks. For the final two weeks, participants could choose which exercise to do. During the last visit, post-intervention listening plans were discussed, and the mindful-music group received a CD or recording of the mindfulness exercises | Mindful music listening is feasible and acceptable post-stroke. The participants’ self-reported positive cognitive effects were primarily related to memory and attention. The music groups, not the audiobook group, reported experiencing memory reminiscence. The mindful music group specifically mentioned an enhanced ability to refocus their mind after it wandered. This indicates improved attentional control or attentional switching |

| Adomavičienė et al[26], 2019 | Lithuania | To assess how new technology influences functional status, cognitive abilities, and upper limb motor outcomes in stroke rehabilitation | Randomized prospective clinical trial | 60 patients who experienced a stroke aged between 60-74 years old, having stroke-affected arm paresis, disturbed deep and superficial sensations, and MMSE score > 21 points were included in the study. Participants with stroke-affected arm paralysis, aphasia, painful shoulder syndrome and hypertonic stroke affected arm were excluded from the study | Fugl-Meyer Assessment upper extremity. Modified Ashworth scale. Box and Block Test. Hand Tapping Score Test. Modified Functional Independence Measure. Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-revised | The conventional post-stroke rehabilitation program lasted for 3-4 h daily, 5 days a week, including various therapies. Training with the new technological devices (Kinect or Armeo robot) took place for 45 min a day, totaling ten sessions. Training sessions involved motor tasks and short rest periods. The exercise program was tailored to each patient, and they received individual supervision from an occupational therapist. Patients sat in a chair or wheelchair with seat belts for safety and were actively engaged in the exercises. The clinician assessed arm impairment, motor function recovery, and any complications at the beginning of each training session | The Armeo group showed greater overall cognitive changes, particularly in attention and executing complex commands like drawing two pentagons. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-revised testing results indicated more substantial enhancements in memory, fluency, and visuospatial abilities within the Armeo group (P < 0.05) |

| Yin et al[40], 2020 | China | To determine the impact of rTMS intervention on patients with post-stroke cognitive impairment to behavioral improvements, including ADL and executive and memory function | Randomized controlled trial | 34 patients with post-stroke cognitive impairment, aged between 30-75 years; MoCA < 26, with stable vital signs, normal cognitive function before stroke, and no severe aphasia were included for the review. Patients with complete left prefrontal cortex injury, transcranial surgery or skull defect, metal or cardiac pacemaker implants, history of brain tumor, brain trauma, seizures, cognitive function recession and affective disorder were excluded from the trial | MoCA. Victoria Stroop test. Rivermead Behavior Memory Test | rTMS treatment was conducted using a MagPro X100 magnetic stimulator and a standard figure-of-eight air-cooled coil. A 10-Hz rTMS was applied at 80% of the resting motor threshold. Patients received treatments once a day, 5 days per week for 4 weeks. After rTMS treatments, they underwent a 30-min computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation program covering various cognitive skills like attention, executive function, memory, calculation, language, and visuospatial skills | A two-way repeated measures ANOVA of the RBMT indicated a significant interaction effect between time and group in terms of memory ability (F = 5.2, df = 2, P = 0.008). After two and four weeks of therapy, pairwise comparisons revealed a substantial rise in the RBMT score for the rTMS group (P < 0.001) |

| Yun et al[27], 2015 | South Korea | To determine if cognitive function of patients who experienced a stroke can be enhanced by tDCS | Prospective, double-blinded, randomized case-control study | 45 patients who experienced a stroke were randomized into two interventional (left-FTAS and right-FTAS) and one control group who had no temporal lobe damage on magnetic resonance imaging and had been diagnosed as acute or sub-acute within six months of their stroke. Patients with apraxia, aphasia, seizure and history of craniotomy were excluded | Korean-MMSE. Computerized neurocognitive function tests. Visual and auditory CPT. DSTs- Forward and backward. Verbal learning tests. Korean version of the MBI | In the tDCS groups, anodal electrodes were placed in alignment with the 10-20 international electroencephalography system. The left-FTAS group had the electrode at T3, while the right-FTAS group had it at T4. Patients in both groups underwent tDCS treatment lasting 30 min, administered five times weekly over a period of 3 weeks. In the sham group, the same method of affixing sponge electrodes was used as in the left-FTAS group, but no electric current was applied. The cognitive rehabilitation program implemented in the study was ComCog, focusing on enhancing attention and memory in patients with cognitive disorders | Left-FTAS group performed significantly better on the Korean-MMSE, the verbal learning test-delayed recall, the visual span test, and the backward DST. In the verbal learning test, the right-FTAS group demonstrated improvement in delayed recall. In the backward visual span test, the sham group performed better. The left-FTAS group had a significant improvement in auditory memory, according to a comparison of pre- and post-treatment data for each group |

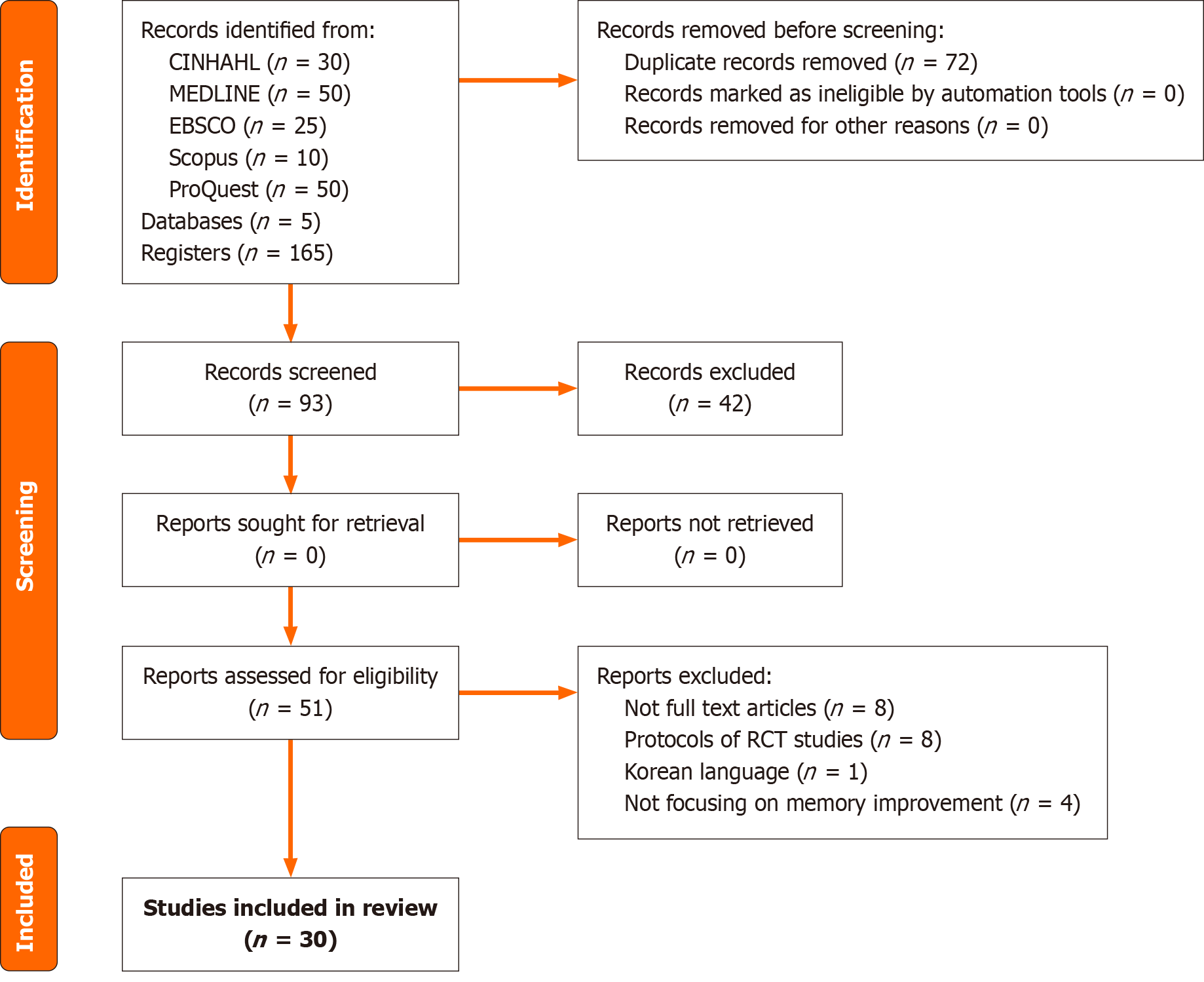

The search extracted a total of 165 studies, with 72 duplicates eliminated, yielding 93 titles and abstracts that were assessed for eligibility. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, 51 full-text studies were reviewed for eligibility. Thirty of the full texts matched the inclusion criteria for the systematic review. Figure 1 depicts the flow diagram of the study selection process.

The characteristics of the included studies considered in this review are summarized in Table 2.

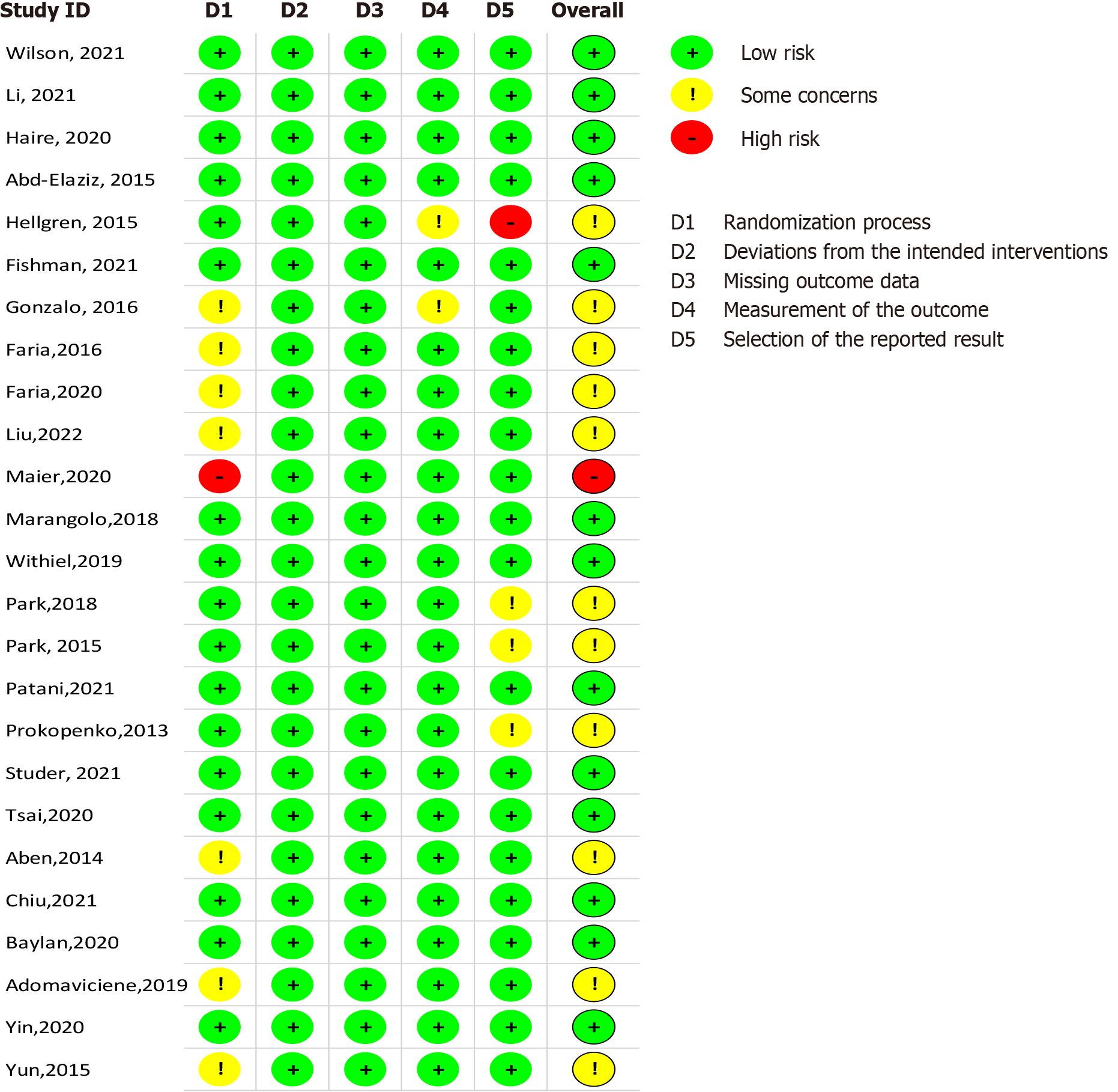

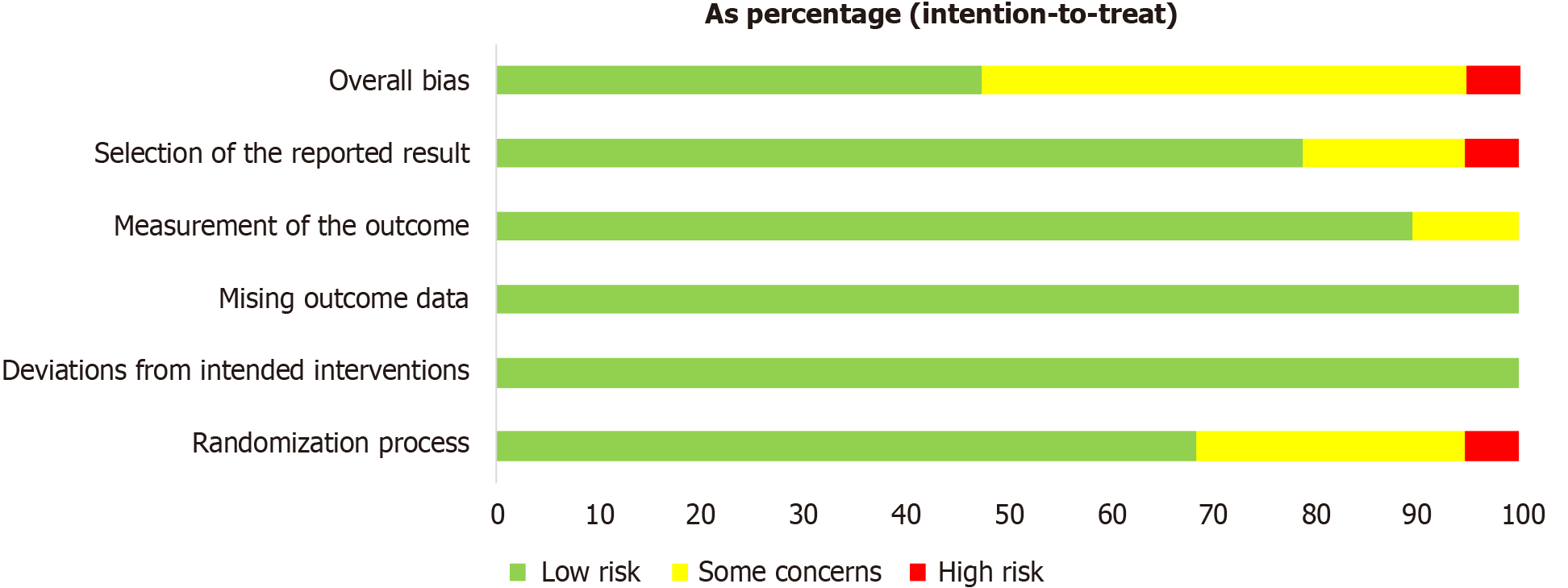

Only one study exhibited a high risk of bias in terms of methodological assessment[20]. All studies demonstrated a low risk of bias in the dimensions of bias due to deviations from intended interventions (D2) and bias due to a lack of data in the results (D3). However, issues with the randomization procedure were reported in seven studies[21-27], potentially impacting the internal validity of these studies by increasing the risk of selection bias. Proper randomization is crucial for ensuring that any observed effects can be confidently attributed to the intervention rather than underlying differences between study groups. Additionally, two studies raised concerns about measurement bias in the assessment of outcome bias (D4), which could affect the reliability of outcome measurements and lead to inaccurate conclusions about the effectiveness of the intervention[21,28].

Three studies were reviewed with noted issues in the quality assessment of the stated outcome (D5), indicating potential variability in outcome reporting or inconsistency in measurement tools, which may influence the comparability of results across studies[29-31]. One study revealed a significant risk of outcome bias, suggesting that its findings should be interpreted cautiously, as they may reflect measurement inaccuracies or selective outcome reporting[28]. Figures 2 and 3 provide a visual summary of the risk of bias assessment across all included studies, highlighting the areas where methodological weaknesses were most prevalent.

In the field of cognitive rehabilitation for patients who experienced a stroke, VR technology has offered innovative solutions. Wilson et al[32] used interactive VR sessions where patients engaged in goal-oriented and exploratory tasks, targeting both unimanual and bimanual movements. It consisted of four goal-based and three exploratory movement tasks involving the manipulation of handheld objects or tangible user interfaces over the surface of a tablet. Unimanual movements involving the weaker and stronger hand were first tested, followed by bimanual movements for the exploratory tasks. These tasks challenged participants with activities ranging from reaching fixed targets to creatively engaging with virtual objects. The cognitive outcomes of the experimental group differed significantly between the pretest and post-test. The magnitude of improvement in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment score was moderate to large, with an effect size of g = 0.70 (t = 2.31, P = 0.036).

In a controlled trial, Faria et al[22] used a virtual city simulation to train patients in daily living tasks, establishing a bridge between the virtual and real worlds and increasing independence in daily life activities. The environmental setting was three-dimensional, featuring streets, sidewalks, buildings, parks, and moving cars. Patients were expected to perform routine everyday tasks at four frequently visited locations: A supermarket; a post office; a bank; and a pharmacy. On the basis of the outcomes of this study, VR-based cognitive rehabilitation considerably improved cognitive functions such as global cognitive performance, attention, memory, visuospatial skills, and executive functions. It also improved subjective health status, physical function, and total recovery. Remarkably, memory in the experimental group improved significantly (Z = 2.081, P = 0.037, r = 0.69).

In a randomized trial, Faria et al[23] evaluated the efficacy of two cognitive rehabilitation interventions for improving memory in patients who experienced a stroke: Personalized and adapted paper-and-pencil training (task generator) and a content-equivalent, ecologically valid VR-based simulation of activities of daily living. Patients were required to perform cognitive tasks associated with daily duties such as reading the newspaper or going shopping. Notably, in the learning and memory test, this intervention outperformed the other interventions in terms of improving general cognitive functioning, visuospatial ability, and executive skills.

Another novel finding was observed in a pre-post design study by Oliveira et al[33], where they evaluated a VR-based approach that mimicked the challenges of daily life activities, with a focus on ecological principles, for assisting in cognitive recovery in patients who experienced a stroke. The primary intervention tool was the Systemic Lisbon Battery, a VR program that simulates daily cognitive tasks in a virtual city. Patients interacted with it via a computer mouse, and patient interactions with the virtual environment were rated by clinicians. The t-tests revealed statistically significant changes, indicating that these scores improved in memory at the post-treatment assessment [WMS memory quotient: t(25) = -3.297; d = 0.39; P value = 0.01], and the modified reliable change index demonstrated significant improvements in memory and attention abilities. This VR cognitive rehabilitation training, which focused on ordinary tasks, may provide patients who experienced a stroke with short-term cognitive rehabilitation benefits[33].

A similar conclusion was reached by Adomavičienė et al[26] who conducted a randomized prospective clinical trial focused on how new technology (Kinect or Armeo robots) influenced functional status, cognitive ability, and upper limb motor outcomes in stroke rehabilitation. Memory improvements were demonstrated when a VR-based intervention was compared with conventional treatment, indicating the benefit of VR serious games for boosting attention and memory tasks in daily activities of patients who experienced a stroke.

Liu et al[24] used an immersive VR (IVR)-based puzzle game as rehabilitation therapy with a focus on improving executive function and visual-spatial attention. The training content of the IVR group was divided into three categories: Life skills training; exergames; and enjoyable games. The difficulty level of each game was graded out of five stars, with one being the easiest and five being the most challenging. Individuals wore head-mounted screens for training and began with a one-star difficulty level that subsequently increased. IVR technology substantially improved executive perfor

Additionally, VR-based interventions also exhibited therapeutic benefits for elderly patients who experienced a stroke, significantly impacting cognitive function and daily living activities. These improvements were more significant when working memory training was initiated early in the rehabilitation process[28]. VR-based cognitive training also showed promise for patients who experienced a stroke and depression, as subgroup analysis revealed lower depression levels and better cognitive improvements with a focus on attention and memory[20]. The cumulative findings highlighted the promising potential of VR-based cognitive rehabilitation interventions in enhancing cognitive function, memory, attention, and overall quality of life among patients who experienced a stroke, offering an innovative and engaging approach to stroke rehabilitation.

Computer-based approaches have also made significant advances in cognitive rehabilitation for patients who experienced a stroke. A randomized controlled trial by Hellgren et al[28] employed the Cogmed program, a computerized working memory training tool that consists of various visuospatial and verbal working memory tasks. Patients engaged in various working motor tasks adapted to their capacities. The study demonstrated that computer-based training could significantly improve motor skills, cognitive performance, and overall activity execution in patients who experienced a stroke.

Similarly, Park and Park[30] conducted a controlled trial to assess the efficacy of the Korean computer-based application CoTrans for cognitive rehabilitation. Visual perception, attention, memory, orientation, sequencing, and categorization were all addressed in this program. The Lowenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment and Motor-free Visual Perception Test-3 improved significantly in this study.

In another study conducted by Maier et al[20], a rehabilitation gaming system (RGS) for daily cognitive training of patients experiencing chronic stroke was used. The goal of this study was to assess whether adaptive conjunctive cognitive training improved attention, spatial awareness, and depressive mood compared with standard cognitive tasks while considering comorbidities.

The RGS framework entailed patients assuming the form of a virtual avatar on a computer screen and participating in conjunctive cognitive training scenarios such as the complex spheroids scenario, which trained basic attention and memory capacities. In the star constellations scenario, patients had to memorize a particular subset of stars in a constellation and then recreate them after a delay period in this visuospatial short-term memory test. The difficulty level of the four task parameters was adjusted to teach spatial attention, spatial memory, working memory, and memory-delayed recall.

The delay time countdown was used as a non-spatial alerting method to train sustained attention. In the quality controller scenario, the patients had to perform two tasks at the same time. They removed doughnuts from a fryer after their cooking time reached the right workspace, and they discovered defective candies on a conveyor belt in the left workspace. The difficulty level of the five task parameters was adjusted to train alertness, visual search ability, selective and sustained attention, inhibition of prepotent reactions, behavior initiation, and response preparation. This scenario also highlighted skills such as divided attention, multitasking, and problem-solving. The experimental group had significant improvements in attention and spatial awareness, whereas the control group simply demonstrated memory improvement.

In a clinical trial conducted by Studer et al[34], patients with visuospatial working memory problems were told to perform 30 min of independently driven repetitive cognitive training every day, utilizing the cognitive training game ‘Wizard,’ in addition to their standard therapy, for a 2-week intervention period. Wizard (Peak) provided tablet-based gamified training for visuospatial memory. Geometrical figures were concealed behind cards in this game. In each round, the cards were turned over one at a time in a randomized order to reveal the hidden figure. One figure was displayed at a time, and the player designated the hiding location by touch screen selection. The Wizard game, as an example of gamified cognitive training, significantly improved working memory abilities in patients who experienced a stroke. Patients who received Wizard instruction improved significantly more than those who did not [F(1,80) = 12.947, Pcorr = 0.002, d = 0.72]. Wizard training was associated with increased improvement in verbal learning capacity on the verbal learning and memory test and in the level of progress. Self-directed training via the Wizard game improved the working memory functions of patients who experienced a stroke.

Jaywant et al[35] proposed a new cognitive rehabilitation technology in their study. The development of a combined executive function intervention in patients experiencing chronic stroke combined computerized cognitive training (CCT) with metacognitive strategy training (MST) to target executive functions and training for transfer to daily compensation-instrumental activities of daily living. Rehacom was selected as the software for the CCT, and the MST component was created via the multicontext method. It included activities to improve attention, working memory, and executive function. These exercises were designed to train low-level executive functions such as attention to detail and processing speed before progressing to higher-level executive functions such as attention, planning, organizing, and problem-solving. The exercises were modified in response to the patient’s performance. The CCT sessions were preceded and followed by guided questioning. These questions were aimed to help participants anticipate obstacles, identify strategies, and make connections between Rehacom exercises and everyday compensation-instrumental activities of daily living. The workbook contained answers to these questions. Workbook tasks were required for both the CCT and MST. Combining the CCT and MST resulted in improved cognitive performance and high participant satisfaction.

Jung et al[36] also used computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation. Ten training activities were used: Two tasks for auditory processing that measured reaction times to auditory stimulation; two tasks for visual processing that measured reaction times to visual stimulation; two tasks for focused attention that evaluated close attention in distractions; three tasks for working memory that measured memory recognition and recall via auditory, visual, and multisensory stimulation; and one task for emotional attention that measured reactions to pleasurable or unpleasant stimulation. According to comparative studies including patients with traumatic brain injury and stroke, improved cognitive function after computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation was observed in patients who experienced a stroke, with focal involvement benefiting the most. Except for the word color test in the stroke group, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (P = 0.000), modified Barthel index (P = 0.000), intelligence quotient (P = 0.002), and all other components of the computerized neuropsychological exam improved significantly. With the exception of the digit span forward test, visual learning test, word color test, and MMSE, all the measures had higher mean values in the stroke group than in the traumatic brain injury group. The stroke group presented significantly higher scores on the visual span forward and card sorting tests.