Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.97415

Revised: November 3, 2024

Accepted: December 2, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 280 Days and 18.5 Hours

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration/biopsy (EUS-FNA/B) is the most common modality for tissue acquisition from pancreatic masses. Despite high specificity, sensitivity remains less than 90%. Auxiliary techniques like elas

To compare the diagnostic outcomes of auxiliary-EUS-FNA/B to standard EUS-FNA/B for pancreatic lesions.

The electronic databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Scopus were searched from inception to February 2024 for all relevant studies comparing diagnostic outcomes of auxiliary-EUS-FNA/B to standard EUS-FNA/B for pancreatic lesions. A bivariate hierarchical model was used to perform the meta-analysis.

A total of 10 studies were identified. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver-operated curve (AUROC) for standard EUS-FNA/B were 0.82 (95%CI: 0.79-0.85), 1.00 (95%CI: 0.96-1.00), and 0.97 (95%CI: 0.95-0.98), respectively. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, and AUROC for EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary techniques were 0.86 (95%CI: 0.83-0.89), 1.00 (95%CI: 0.94-1.00), and 0.96 (95%CI: 0.94-0.98), respectively. Comparing the two diagnostic modalities, sensitivity [Risk ratio (RR): 1.04, 95%CI: 0.99-1.09], specificity (RR: 1.00, 95%CI: 0.99-1.01), and diagnostic accuracy (RR: 1.03, 95%CI: 0.98-1.09) were comparable.

Analysis of the currently available literature did not show any additional advantage of EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary techniques for pancreatic solid lesions over standard EUS-FNA/B. Further randomized studies are required to demonstrate the benefit of auxiliary techniques before they can be recommended for routine practice.

Core Tip: Auxiliary techniques like elastography and contrast enhancement are being used during endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration/biopsy (EUS-FNA/B) to guide tissue acquisition from viable tumor tissue and improve diagnostic outcomes. However, the present meta-analysis reported comparable sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy between EUS-FNA/B with and without auxiliary techniques. Subgroup analysis of studies exclusively using contrast-enhanced harmonic-EUS-FNA/B, randomized studies, and studies reporting diagnostic outcomes after the first pass reported no difference between both modalities. Thus, using EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary techniques for pancreatic solid lesions does not provide any additional advantage over standard EUS-FNA/B.

- Citation: Rath MM, Anirvan P, Varghese J, Tripathy TP, Patel RK, Panigrahi MK, Giri S. Comparison of standard vs auxiliary (contrast or elastography) endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration/biopsy in solid pancreatic lesions: A meta-analysis. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 97415

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/97415.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.97415

The assessment of pancreatic head lesions has been greatly aided by the development of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration/biopsy (EUS-FNA/B). EUS-FNA/B has a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 84%–92%, 96%–98%, and 86%–91%, respectively, in diagnosing malignant pancreatic masses[1]. The sensitivity depends upon several factors – the type of needle used, use of suction, stylet, use of rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) or macroscopic on-site evaluation, and indwelling biliary stent[2-6]. The median survival in patients of pancreatic cancer who don’t receive a diagnosis on time and present with distant metastases is 8–12 months and 3–6 months, respectively[7]. On the flip side, the diagnosis of mass-forming chronic pancreatitis as pancreatic cancer, often to the tune of 5% to 35%[8], leads to unnecessary psychological trauma and needless surgeries. Auxiliary techniques that have been developed to increase the sensitivity and accuracy of EUS-FNA/B include real-time elastography (RTE)-EUS-FNA/B and contrast-enhanced harmonic (CEH)-EUS-FNA/B[9].

CEH-EUS-FNA/B uses a contrast agent with harmonic imaging to characterize tissue blood flow within the pancreatic masses and differentiate benign from malignant masses. The technique relies on generating a time-intensity curve (TIC) based on the temporal change in intensity of echo enhancement. CEH-EUS-FNA/B can differentiate benign from malignant pancreatic lesions[10]. For malignant lesions, the TIC is flat and low compared to benign lesions since the desmoplastic nature of the lesion limits blood supply[10]. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of CEH-EUS-FNA/B for diagnosis of pancreatic cancer are 91% and 86%, respectively[11]. However, there is a lack of uniformity concerning the standard cut-off values of TIC. CEH-EUS-FNA/B is also operator-dependent, and the endoscopist's experience may affect the results[12].

There have been conflicting results in studies comparing CEH-EUS-FNA/B to standard EUS-FNA/B. The aim of this meta-analysis was to compare the diagnostic outcome of auxiliary-EUS-FNA/B compared to standard EUS-FNA/B in the diagnosis of pancreatic solid lesions.

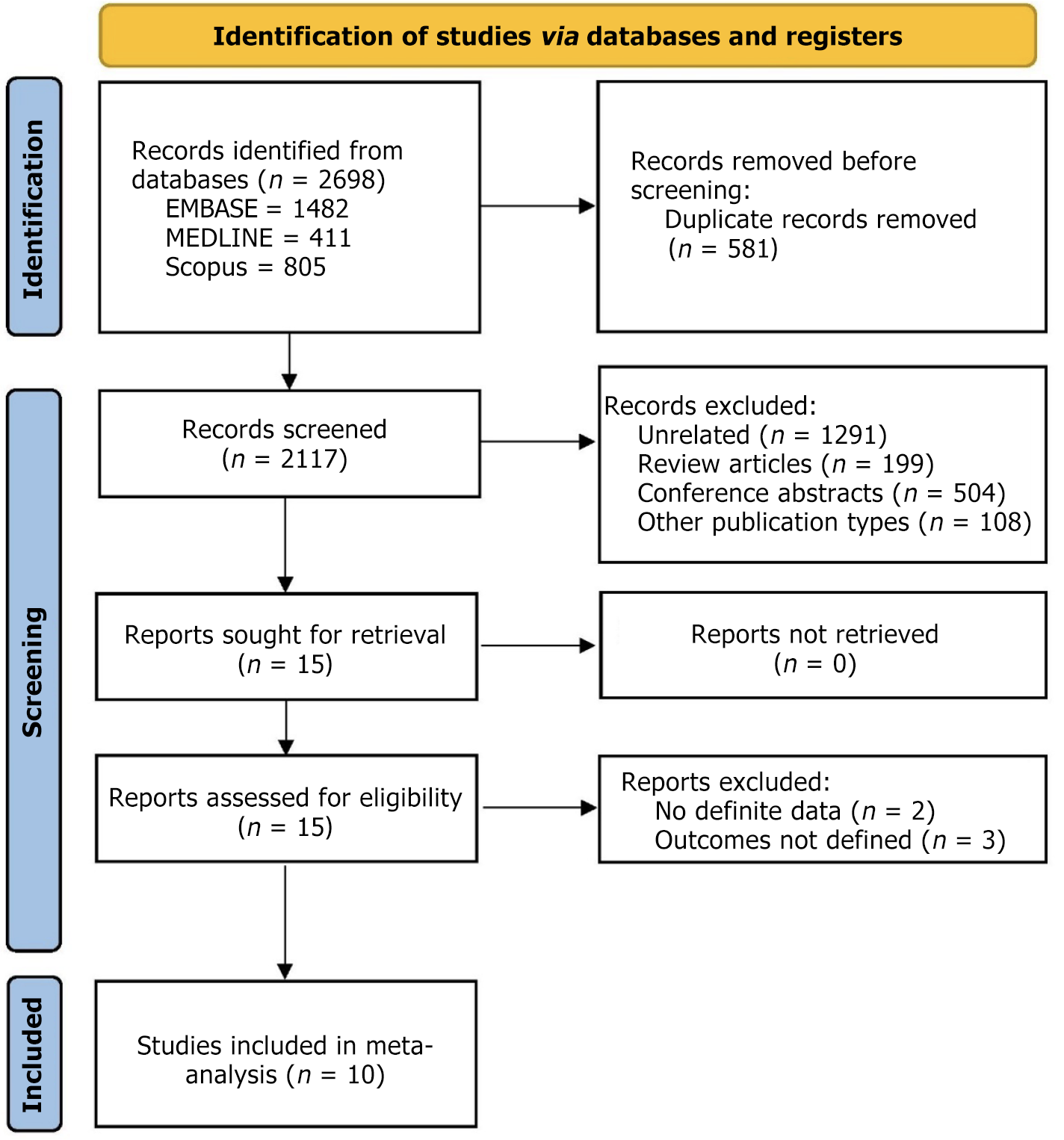

The present meta-analysis was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[13].

The electronic databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Scopus were searched from their inception to February 2024 for all relevant studies. The following keywords were used for the search: (Endoscopic ultrasound OR EUS) AND (FNA OR Fine needle aspiration OR FNB OR Fine needle biopsy) AND (Elastography OR Contrast) AND (Pancreas OR Pancreatic). Furthermore, relevant studies were searched from the reference lists of all retrieved studies, guidelines, and reviews.

Two reviewers independently reviewed the obtained search records for inclusion and exclusion criteria from the titles and abstracts. The same independent reviewers went through the full text of the shortlisted articles. Any dispute was settled by a third reviewer. Comparative prospective and retrospective studies (parallel as well as cross-over) fulfilling the following criteria were included in this meta-analysis: (1) Participants-patients with a solid pancreatic lesion; (2) Index test-RTE-EUS-FNA/B or CEH-EUS-FNA/B; (3) Comparator test-Standard EUS-FNA/B; and (4) Reference standards-surgical pathology for patients who underwent surgery or clinical and radiological follow-up of 12 months in unresectable cases. Conference abstracts, non-comparative single-arm studies, and case reports were excluded from the analysis.

Two reviewers worked independently to retrieve the data. A third reviewer arbitrated any disputes. The following categories were utilized to gather data: Author and publication year, number of patients, age distribution, location and size of the lesion, type of needle and technique used, and the diagnostic outcomes.

The risk of bias and applicability in the included studies were evaluated using the QUADAS-2 tool[14]. Patient selection, index test, reference standard, and patient flow during the research and timing of the index tests are the four domains that make up this tool.

The sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio (LR), and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) were determined using the true positive, false positive, false negative, and true negative data. The receiver operating characteristic curve (sROC) was summarized, and the area under the ROC (AUROC) was computed. The bivariate hierarchical model was used for meta-analysis of the summary estimate for sensitivity and specificity together, whereas the hierarchical summary ROC model was used to model the parameters for the sROC curve. The bivariate model models the sensitivity and specificity more directly, assuming that their logit (log-odds) transforms have a bivariate normal distribution between studies[15]. In random-effects meta-analysis, the extent of variation among the effects observed in different studies is referred to as tau-squared (τ2), which is a measure of heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the reliability of the study's findings. Based on the LR of the diagnostic test, a Fagan nomogram was utilized to calculate the post-test probability. A P value of < 0.10 for the slope coefficient in Deek's plot indicated publication bias[16]. Data analysis was performed using Meta-DiSc version 1.4 (Madrid, Spain), RevMan version 5.4, and STATA version 17 (College Station, Tex).

Ten studies out of the 2698 retrieved records were included in the meta-analysis. The PRISMA flowchart for the inclusion and selection of studies is displayed in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of the studies that were included in the meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1[17-26]. Only one study used RTE-EUS-FNA/B[24], while the other nine used CEH-EUS FNA/B. Five of these nine studies on CEH-EUS FNA/B used SonoVue[17,18,20,22,23], and four used Sonazoid[19,21,25,26]. Four studies were randomized trials[19,22,23,26], three were prospective[18,21,24], and three were retrospective[17,20,25]. The mean size of the lesion varied from 25 mm to 39.5 mm. Except for two studies[19,23], the rest all used a 22-G size needle. ROSE was available in only two studies. The study by Lai et al[25] reported data from only malignant lesions[25] and, hence, was not included in the calculation of sensitivity and specificity. Concerning study quality, three studies had low[22,24,26], four had intermediate[18,19,21,23], and three had high risk of bias[17,20,25] (Figure 2).

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Arm | Number of patients | Age | Lesion size, in mm | Lesion location (H/U-B/T) | Contrast | Needle | Suction | Number of passes | ROSE |

| Hou et al[17] | China | Retrospective | CEH-EUS FNA | 58 | 55.1 ± 11.7 | 38 ± 12 | 35/23 | SonoVue | 22-G | - | 3.7 ± 0.9 | No |

| EUS-FNA | 105 | 56.2 ± 12.5 | 39 ± 8.0 | 65/40 | - | 3.6 ± 0.8 | ||||||

| Seicean et al[18] | Romania | Prospective, cross-over | CEH-EUS FNA | 51 | 64 (39-83) | 35 | 31/10 | SonoVue | 22-G | - | 2 | No |

| EUS-FNA | - | 2 | ||||||||||

| Sugimoto et al[19] | Japan | RCT | CEH-EUS FNA | 20 | 69.5 ± 10.5 | 25.0 ± 8.0 | 13/7 | Sonazoid | 22-G | DS | 1-5 | Yes |

| EUS-FNA | 20 | 67.1 ± 9.9 | 26.5 ± 9.2 | 13/7 | - | 22-G or 25-G | 1-5 | |||||

| Facciorusso et al[20] | Italy | Retrospective | CEH-EUS FNA | 103 | 66 ± 6 | 32 ± 11 | 71/32 | SonoVue | 22-G | DS | 2.4 ± 0.6 | No |

| EUS-FNA | 103 | 66 ± 8 | 32 ± 10 | 71/32 | - | 2.7 ± 0.8 | ||||||

| Itonaga et al[21] | Japan | Prospective, cross-over | CEH-EUS FNA | 93 | 72.5 (34–89) | 25.2 (12-56) | 55/38 | Sonazoid | 22-G | DS | 2.6 (2-5) | No |

| EUS-FNA | - | |||||||||||

| Seicean et al[22] | Romania | RCT, cross-over | CEH-EUS FNA | 148 | 64.5 (62.6 – 66.3) | 30 (20.8- 35) | 103/45 | SonoVue | 22-G | - | 1 | No |

| EUS-FNA | - | 1 | ||||||||||

| Cho et al[23] | South Korea | RCT | CEH-EUS FNA/B | 120 | 66.3 ± 11.8 | 30.9 ± 2.1 | 54/66 | SonoVue | 19- to 25-G | DS | 1-5 | No |

| EUS-FNA/B | 120 | 68.3 ± 11.9 | 33.1 ± 16.4 | 60/60 | - | 1-5 | ||||||

| Gheorghiu et al[24] | Romania | Prospective, cross-over | RTE-EUS FNA | 60 | 66.4 ± 10.0 | 30 (29.5 -35) | 44/16 | - | 22-G | No | 1 | No |

| EUS-FNA | - | 1 | ||||||||||

| Lai et al[25] | Taiwan | Retrospective | CEH-EUS FNB | 48 | 63.6 ± 12.6 | 29.5 ± 11.5 | 29/11/8 | Sonazoid | 22-G | SSP | 2.2 ± 0.7 | No |

| EUS-FNB | 85 | 34.8 ± 18.2 | 39/36/10 | - | 3.6 ± 1.2 | |||||||

| Kuo et al[26] | Taiwan | RCT | CEH-EUS FNB | 59 | 64.7 ± 11.6 | 37.5 (28.8-45.9) | 30/29 | Sonazoid | 22-G | No | 1-6 | Yes |

| EUS-FNB | 59 | 64.1 ± 12.6 | 37.5 (30.6-46.2) | 34/25 | - | 1-6 |

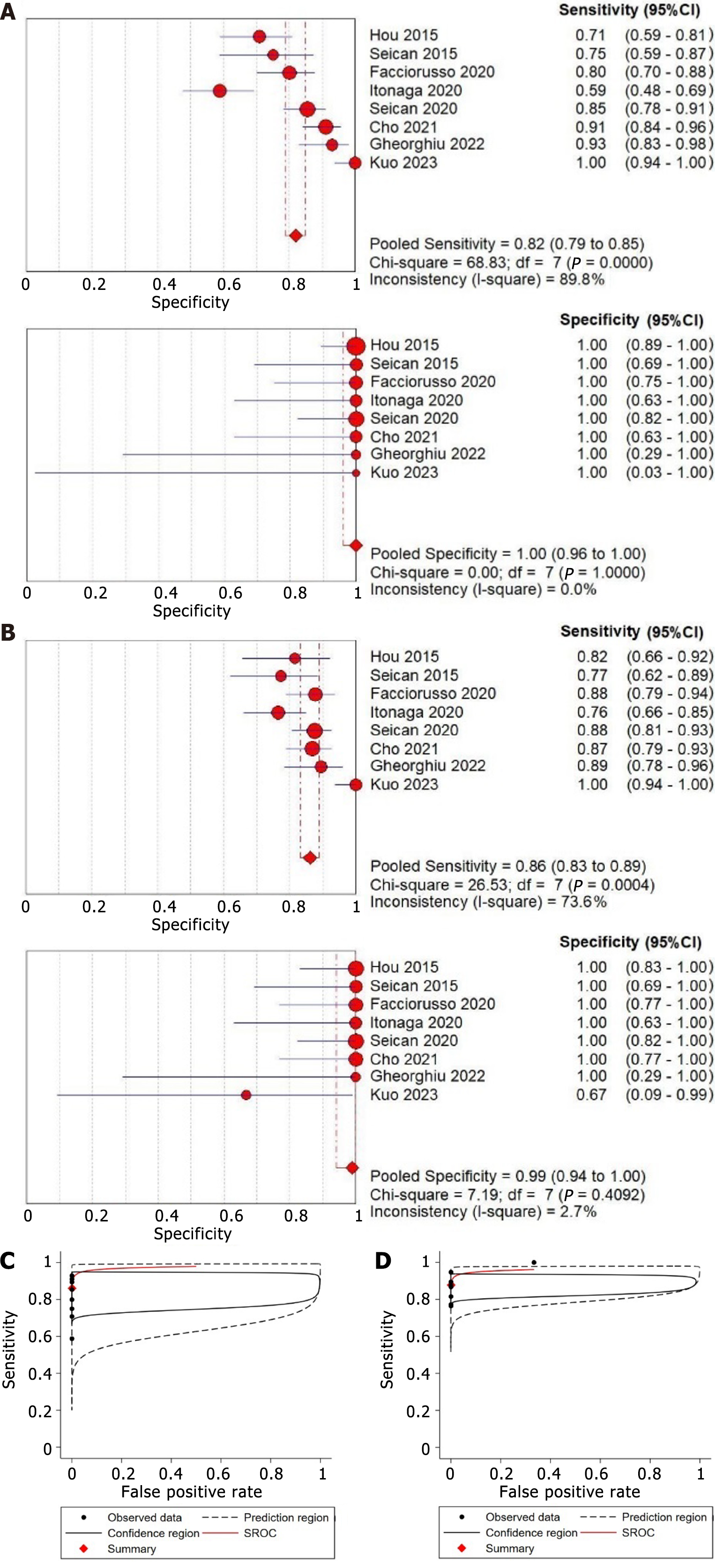

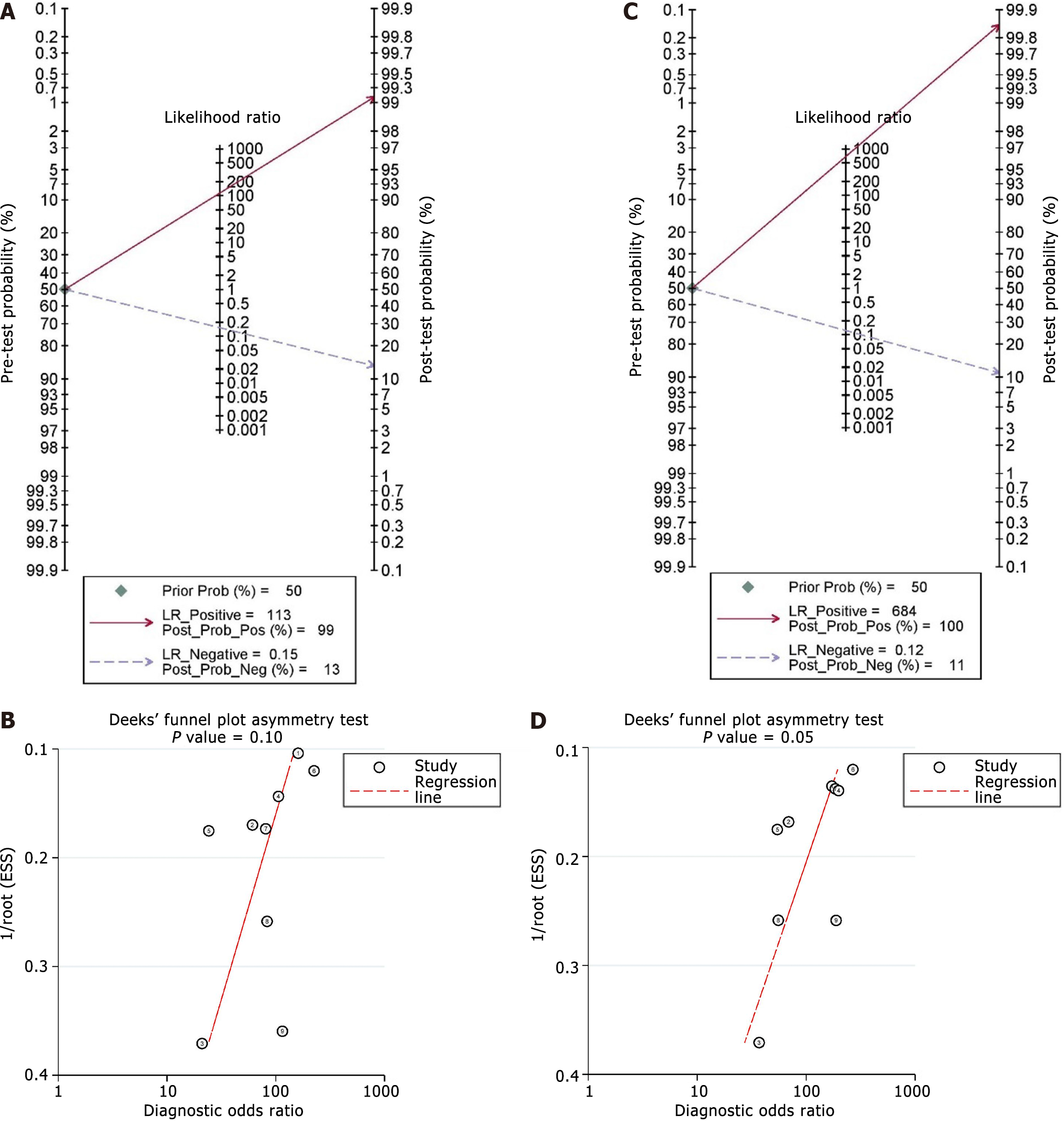

The pooled sensitivity estimates of standard EUS-FNA/B was 0.82 (95%CI: 0.79-0.85) (I2 = 89.8%), and the pooled specificity estimate was 1.00 (95%CI: 0.96-1.00) (I2 = 0.0%) (Figure 3A). Additionally, the pooled positive LR, negative LR, and DOR were 14.42 (95%CI: 5.64-36.90), 0.19 (95%CI: 0.13-0.30), and 105.51 (95%CI: 36.38-305.99), respectively (Table 2). Using the Fagan nomogram, a positive result raised the pre-test likelihood of diagnosis from 50% to 99%, whereas a negative result lowered the pre-test probability from 50% to 13% (Figure 4A). An sROC curve was plotted, and the AUROC with 95%CI was 0.97 (95%CI: 0.95-0.98) (Figure 3C).

| Parameters | Standard EUS-FNA/B | EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary techniques | ||

| Values with 95%CI | Heterogeneity (I2) | Values with 95%CI | Heterogeneity (I2) | |

| Sensitivity | 0.82 (0.79-0.85) | 89.8% | 0.86 (0.83-0.89) | 73.6% |

| Specificity | 1.00 (0.96-1.00) | 0.0% | 1.00 (0.94-1.00) | 2.7% |

| Positive LR | 14.42 (5.64-36.90) | 0.0% | 11.11 (4.30-28.71) | 21.6% |

| Negative LR | 0.19 (0.13-0.30) | 82.5% | 0.17 (0.13-0.22) | 40.4% |

| DOR | 105.51 (36.38-305.99) | 0.0% | 126.87 (44.43-362.28) | 0.0% |

| AUROC | 0.97 (0.95-0.98) | - | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | - |

The pooled sensitivity estimate was 0.86 (95%CI: 0.83-0.89) (I2 = 73.6%), and the pooled specificity estimate was 1.00 (95%CI: 0.94-1.00) with evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 2.7%) (Figure 3B). The pooled positive LR, negative LR, and DOR for EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary techniques were 11.11 (95%CI: 4.30-28.71), 0.17 (95%CI: 0.13-0.22), and 126.87 (95%CI: 44.43-362.28), respectively (Table 2). Using the Fagan nomogram, a positive result raised the pre-test likelihood of diagnosis from 50% to 100%, whereas a negative result reduced the pre-test probability from 50% to 11% (Figure 4C). An sROC curve was plotted, and the AUROC with 95%CI was 0.96 (95%CI: 0.94-0.98) (Figure 3D).

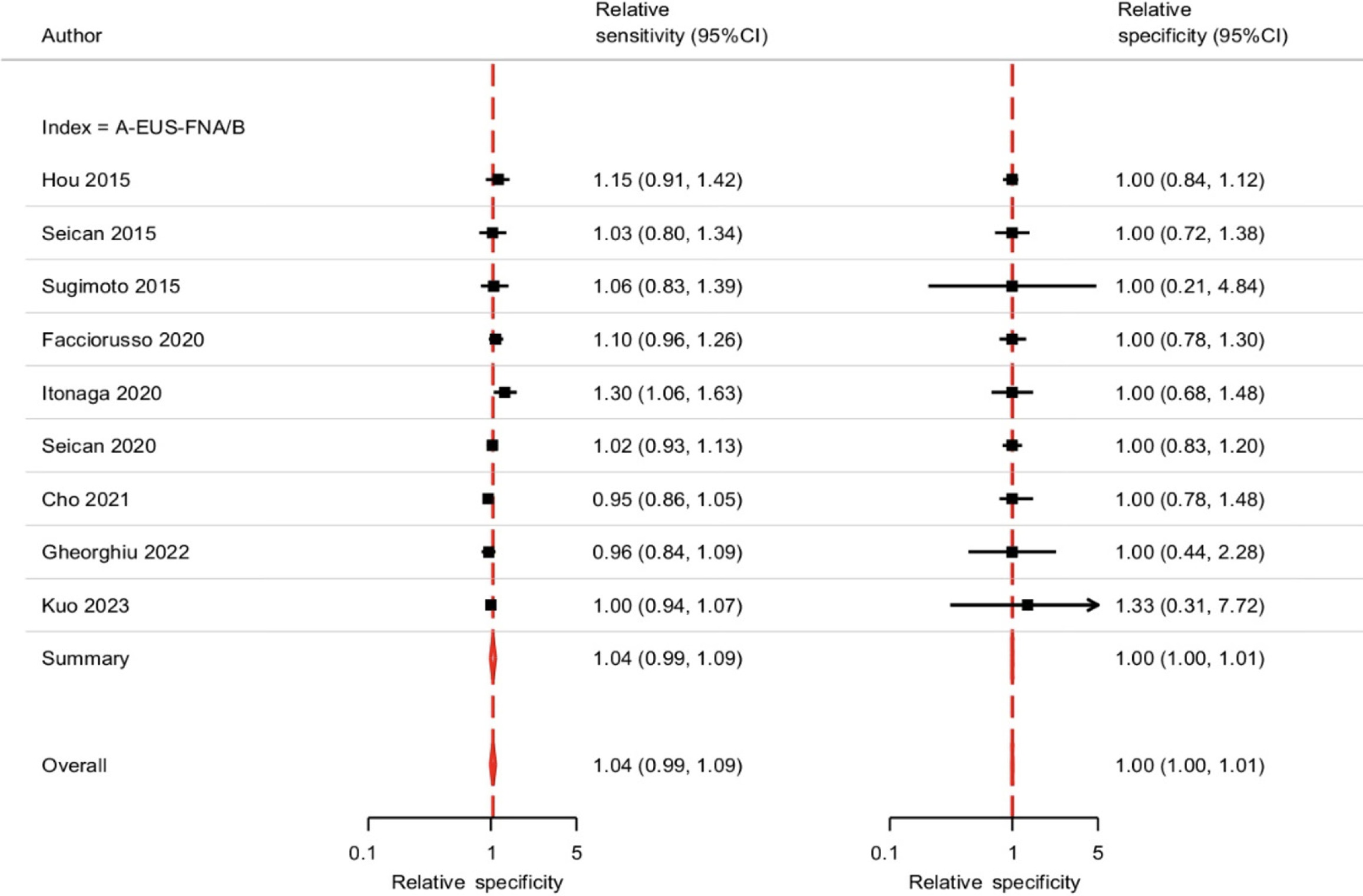

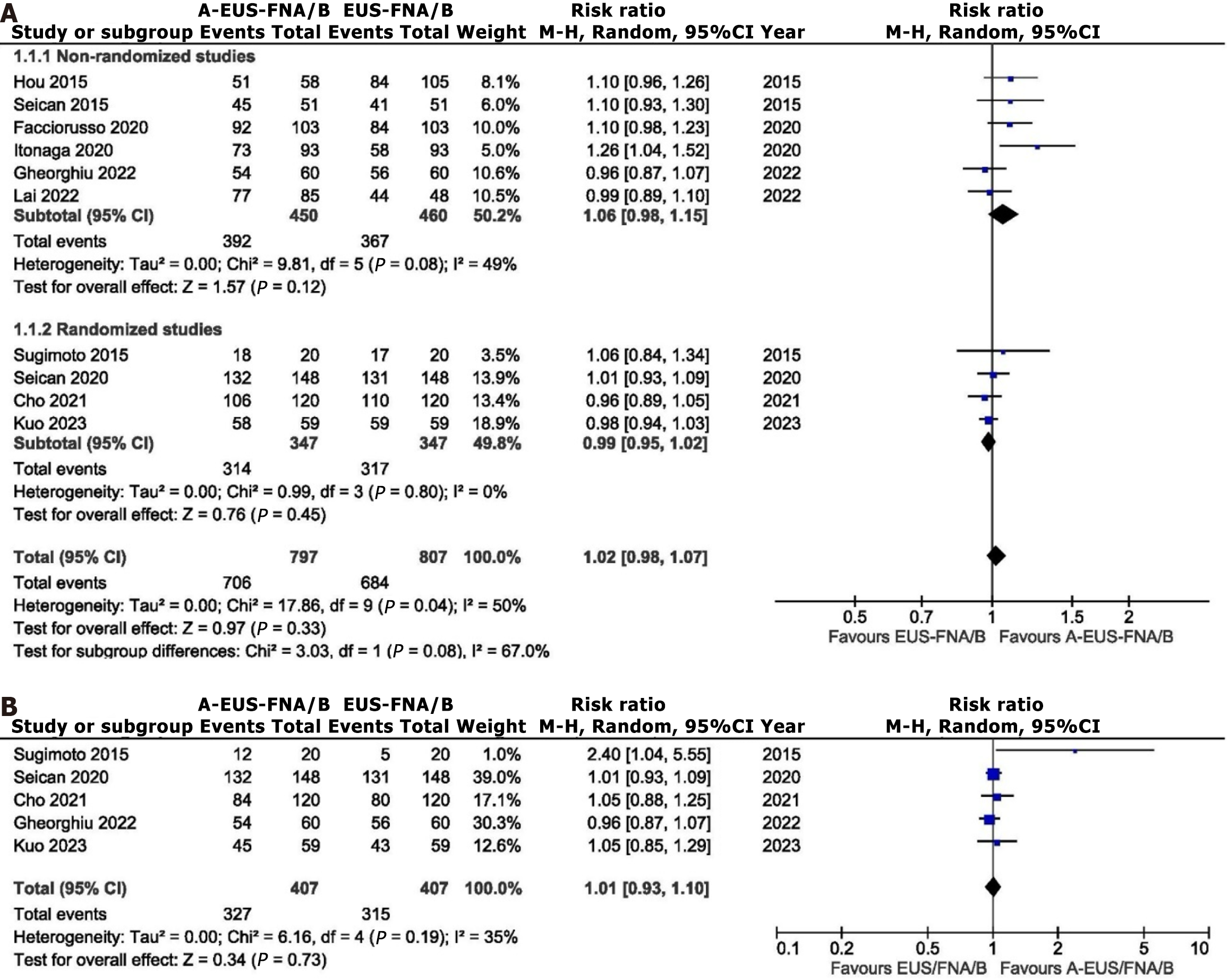

On comparison of standard vs auxiliary EUS-FNA/B, both sensitivity [Risk ratio (RR): 1.04, 95%CI: 0.99-1.09, P = 0.0828; τ2 = 0.91] and specificity (RR: 1.00, 95%CI: 0.99-1.01, P = 0.8123; τ2 = 8.41) were comparable (Figure 5). The diagnostic accuracy between the two modalities (RR: 1.02, 95%CI: 0.98-1.07; I2 = 50%, P = 0.04) was also comparable, with evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Figure 6).

Assessment of Deeks’ plot did not show evidence of publication bias for standard EUS-FNA/B (Figure 4B) but for EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary technique (P = 0.054) (Figure 4D). A sensitivity analysis was conducted using studies on CEH-EUS-FNA/B, randomized studies, and first-pass data. Sensitivity analysis showed comparable sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy between both groups (Table 3). Table 4 shows the certainty of evidence for the analyzed outcomes.

| Comparison of EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary vs standard techniques | No. of studies | Relative risk | P value | Tau2 |

| Relative sensitivity | ||||

| Overall | 9 | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | 0.0828 | 0.91 |

| Studies with CEH-EUS-FNA/B | 8 | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) | 0.0729 | 1.05 |

| Randomized studies | 4 | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.9006 | 1.41 |

| Relative specificity | ||||

| Overall | 9 | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.8123 | 0.41 |

| Studies with CEH-EUS-FNA/B | 8 | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.8096 | 8.42 |

| Randomized studies | 4 | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) | 0.7840 | 6.31 |

| I2 | ||||

| Diagnostic accuracy | ||||

| Overall | 10 | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) | 0.33 | 50% |

| Studies with CEH-EUS-FNA/B | 9 | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) | 0.23 | 55% |

| After single pass | 5 | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | 0.19 | 35% |

| Randomized studies | 4 | 0.99 (0.95-1.02) | 0.45 | 0% |

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95%CI) | Relative effect (95%CI) | No. of patients (studies) | Certainty assessment | Overall certainty of evidence | ||||

| With standard EUS-FNA/B | With EUS-FNA/B and auxiliary techniques | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | ||||

| Sensitivity | 0.82 (0.79-0.85) | 0.86 (0.83-0.89) | RR: 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | 1471 (9 studies) | + | + | - | - | Low |

| Specificity | 1.00 (0.96-1.00) | 1.00 (0.94-1.00) | RR: 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 1471 (9 studies) | + | + | - | - | Low |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 846 per 1000 | 17 higher per 1000 (17 lower to 59 more) | RR: 1.02 (0.98-1.07) | 1604 (10 studies) | + | + | - | - | Low |

EUS-guided advanced imaging techniques, such as elastography and contrast enhancement, offer the advantage of distinguishing between fibrotic/inflammatory tissues and malignant pancreatic lesions. These auxiliary techniques have been touted to improve the diagnostic performance of EUS in solid pancreatic lesions, and a recent guideline recommends using contrast guidance for EUS-guided tissue acquisition from solid lesions with avascular areas[27]. However, there is a paucity of data to support this argument fully. The present meta-analysis reported pooled sensitivity estimates of standard EUS-FNA/B and EUS-FNA/B with auxiliary technique as 82% (79%-85%) and 86% (83%-89%), without any significant difference (1.04, 95%CI: 0.99-1.09). Similarly, the pooled specificity estimates of standard EUS-FNA/B and EUS-FNA/B with the auxiliary technique were 100% (96%-100%) and 100% (94%-100%) with relative specificity of 1.00 (95%CI: 1.00-1.01). The odds of diagnostic accuracy were comparable also comparable between both groups (1.03, 95%CI: 0.98-1.09). These findings suggest that the auxiliary techniques may not improve the diagnostic outcome of EUS-FNA/B.

Other factors that may affect diagnostic outcomes of EUS-FNA/B include the size and location of the lesion. Itonaga et al[21] reported higher adequacy and sensitivity with CEH-EUS-FNA in lesion size > 15 mm and lesions located in the body/tail[21]. Kuo et al[26] reported reduced cytologic and histologic accuracy in lesions larger than 40 mm[26]. This may be due to the increased proportion of necrotic material in larger lesions. CEH-EUS may help target viable tissue in such lesions. However, Facciorusso et al[20] and Seicean et al[22] reported no difference with respect to size[20,22], and Cho et al[23] reported no difference with respect to the location of the lesion[23]. Hence, further studies are required to demonstrate the benefit of CEH-EUS-FNA/B in larger lesions.

Another benefit of the auxiliary technique, which has been reported in some studies, is the higher diagnostic yield in a single pass. Sugimoto et al[19] reported that a sufficient biopsy sample after a single needle pass was obtained in 60% of the CEH-EUS-FNA group compared with 25% of the standard EUS-FNA group[19]. Similarly, the rate of adequate sampling and sensitivity of one pass with EUS-FNA-CHI was higher in the study by Itonaga et al[21]. However, the studies by Cho et al[23] and Kuo et al[26] reported no difference in the diagnostic sensitivity after the first needle pass between the two techniques[23,25]. One reason for this difference between the studies may be that Sugimoto et al[19] and Itonaga et al[21] used FNA needles, while Cho et al[23] and Kuo et al[26] used FNB needles predominantly. However, a recent RCT using an FNA needle reported no significant difference between conventional and CEH-EUS-FNA in terms of diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values[28]. Also, a meta-analysis using the data on first-pass from four studies showed no difference in the diagnostic accuracy. Thus, with the increasing use of newer-generation FNB needles, auxiliary techniques may not be useful as a routine procedure.

Despite some studies highlighting the utility of CH-EUS-FNA, only one study has shown that CH-EUS-FNA enhances diagnostic sensitivity[21]. With the advent of precision medicine, particularly in the realm of oncogene panel testing on EUS-FNA specimens, it will be crucial to obtain cancer tissues from sites with a high cellular yield[29]. In this context, CH-EUS-FNA could be a valuable technique, especially for collecting tissue samples from solid pancreatic neoplasms. The ability of CH-EUS-FNA to provide high-quality, cell-rich samples can make it an indispensable tool in the advancement of personalized treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer patients, underscoring its significance in the diagnostic and therapeutic landscape of pancreatic cancer[30].

EUS elastography is being promoted because it offers important information complementary to B-mode imaging. However, elastography cannot be considered a required addition to EUS because most endosonographers achieve excellent EUS outcomes without it. No evidence indicates that elastography enhances clinical outcomes compared to traditional EUS, whether or not EUS-guided tissue acquisition is used. Specifically, no studies demonstrate that elastography is superior in targeting cancer within suspicious lesions. Despite its high sensitivity for diagnosing malignancy, the clinical utility of EUS elastography is limited by its low specificity. In one large prospective study, the specificity for characterizing solid pancreatic lesions was as low as 22%, undermining its overall effectiveness in clinical practice[31]. In addition, it has been observed that the accuracy of EUS-FNA largely depends on the expertise of the endosonographers and similarly, the evaluation of pancreatic lesions using CH-EUS or elastography is also reliant on their examination skills[32].

The other disadvantage of the contrast agent is that it is expensive, costing approximately $250 per bottle, and requires an additional 3 to 5 minutes to prepare the contrast injection and observe the enhancement pattern[26]. This information is valuable for healthcare providers and policy-makers aiming to optimize resource allocation. However, none of the studies compared the overall difference in cost between the two modalities.

There are a few limitations to the present analysis warranting discussion. First, not all studies were randomized, increasing the risk of selection and reporting bias. However, a subgroup analysis of randomized studies did not report any difference between both modalities. Second, an assessment of publication bias, using the Deeks plot, revealed the presence of publication bias for the auxiliary techniques. This suggests that the studies included in the analysis may not fully represent the entire spectrum of clinical scenarios, and the results should be interpreted cautiously. Third, we could not perform a meta-analysis to assess the impact of size on diagnostic outcomes due to limited data from the included studies. Fourth, there was heterogeneity concerning the type of needle, type of suction method, and use of ROSE. Fifth, we did not compare the occurrence of adverse effects between the two modalities. However, the existing literature does not suggest any increase in adverse events using auxiliary techniques. The reported adverse effects related to the use of ultrasound contrast medium do not pose any clinical problems[33].

In conclusion, EUS-FNA/B, both standard and with auxiliary techniques, demonstrates high diagnostic utility with excellent specificity. Comparable sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy were reported in the current meta-analysis comparing EUS-FNA/B with and without auxiliary techniques. Subgroup analysis of studies exclusively using CEH-EUS-FNA/B, randomized studies, and studies reporting diagnostic outcomes after the first pass reported no difference between both modalities. Thus, the currently available literature for pancreatic solid lesions does not show any additional benefit from utilizing auxiliary techniques in conjunction with standard EUS-FNA/B. Further randomized studies are required before auxiliary techniques can be recommended for routine practice.

| 1. | Yang Y, Li L, Qu C, Liang S, Zeng B, Luo Z. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle core biopsy for the diagnosis of pancreatic malignant lesions: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yao DW, Qin MZ, Jiang HX, Qin SY. Comparison of EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB for diagnosis of solid pancreatic mass lesions: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2024;59:972-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Giri S, Afzalpurkar S, Angadi S, Marikanty A, Sundaram S. Comparison of suction techniques for EUS-guided tissue acquisition: Systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endosc Int Open. 2023;11:E703-E711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sundaram S, Chhanchure U, Patil P, Seth V, Mahajan A, Bal M, Kaushal RK, Ramadwar M, Prabhudesai N, Bhandare M, Shrikhande SV, Mehta S. Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) versus macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE) for endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling of solid pancreatic lesions: a paired comparative analysis using newer-generation fine needle biopsy needles. Ann Gastroenterol. 2023;36:340-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Giri S, Uppin MS, Kumar L, Uppin S, Pamu PK, Angadi S, Bhrugumalla S. Impact of macroscopic on-site evaluation on the diagnostic outcomes of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2023;51:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Giri S, Afzalpurkar S, Angadi S, Varghese J, Sundaram S. Influence of biliary stents on the diagnostic outcome of endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition from solid pancreatic lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Endosc. 2023;56:169-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55825] [Article Influence: 7975.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 8. | Wolske KM, Ponnatapura J, Kolokythas O, Burke LMB, Tappouni R, Lalwani N. Chronic Pancreatitis or Pancreatic Tumor? A Problem-solving Approach. Radiographics. 2019;39:1965-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Costache MI, Cazacu IM, Dietrich CF, Petrone MC, Arcidiacono PG, Giovannini M, Bories E, Garcia JI, Siyu S, Santo E, Popescu CF, Constantin A, Bhutani MS, Saftoiu A. Clinical impact of strain histogram EUS elastography and contrast-enhanced EUS for the differential diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses: A prospective multicentric study. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Spadaccini M, Koleth G, Emmanuel J, Khalaf K, Facciorusso A, Grizzi F, Hassan C, Colombo M, Mangiavillano B, Fugazza A, Anderloni A, Carrara S, Repici A. Enhanced endoscopic ultrasound imaging for pancreatic lesions: The road to artificial intelligence. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:3814-3824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Mei S, Wang M, Sun L. Contrast-Enhanced EUS for Differential Diagnosis of Pancreatic Masses: A Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:1670183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang J, Zhu L, Yao L, Ding X, Chen D, Wu H, Lu Z, Zhou W, Zhang L, An P, Xu B, Tan W, Hu S, Cheng F, Yu H. Deep learning-based pancreas segmentation and station recognition system in EUS: development and validation of a useful training tool (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:874-885.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 40506] [Article Influence: 10126.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6953] [Cited by in RCA: 9580] [Article Influence: 684.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Leeflang MM, Deeks JJ, Takwoingi Y, Macaskill P. Cochrane diagnostic test accuracy reviews. Syst Rev. 2013;2:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:882-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1792] [Cited by in RCA: 2228] [Article Influence: 111.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Hou X, Jin Z, Xu C, Zhang M, Zhu J, Jiang F, Li Z. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions: a retrospective study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Seicean A, Badea R, Moldovan-Pop A, Vultur S, Botan EC, Zaharie T, Săftoiu A, Mocan T, Iancu C, Graur F, Sparchez Z, Seicean R. Harmonic Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasonography for the Guidance of Fine-Needle Aspiration in Solid Pancreatic Masses. Ultraschall Med. 2017;38:174-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sugimoto M, Takagi T, Hikichi T, Suzuki R, Watanabe K, Nakamura J, Kikuchi H, Konno N, Waragai Y, Watanabe H, Obara K, Ohira H. Conventional versus contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions: A prospective randomized trial. Pancreatology. 2015;15:538-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Facciorusso A, Cotsoglou C, Chierici A, Mare R, Crinò SF, Muscatiello N. Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration versus Standard Fine-Needle Aspiration in Pancreatic Masses: A Propensity Score Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Itonaga M, Kitano M, Kojima F, Hatamaru K, Yamashita Y, Tamura T, Nuta J, Kawaji Y, Shimokawa T, Tanioka K, Murata SI. The usefulness of EUS-FNA with contrast-enhanced harmonic imaging of solid pancreatic lesions: A prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:2273-2280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Seicean A, Samarghitan A, Bolboacă SD, Pojoga C, Rusu I, Rusu D, Sparchez Z, Gheorghiu M, Al Hajjar N, Seicean R. Contrast-enhanced harmonic versus standard endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in solid pancreatic lesions: a single-center prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2020;52:1084-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cho IR, Jeong SH, Kang H, Kim EJ, Kim YS, Cho JH. Comparison of contrast-enhanced versus conventional EUS-guided FNA/fine-needle biopsy in diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:303-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gheorghiu M, Sparchez Z, Rusu I, Bolboacă SD, Seicean R, Pojoga C, Seicean A. Direct Comparison of Elastography Endoscopic Ultrasound Fine-Needle Aspiration and B-Mode Endoscopic Ultrasound Fine-Needle Aspiration in Diagnosing Solid Pancreatic Lesions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lai JH, Lin CC, Lin HH, Chen MJ. Is contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy better than conventional fine needle biopsy? A retrospective study in a medical center. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:6138-6143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kuo YT, Chu YL, Wong WF, Han ML, Chen CC, Jan IS, Cheng WC, Shun CT, Tsai MC, Cheng TY, Wang HP. Randomized trial of contrast-enhanced harmonic guidance versus fanning technique for EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy sampling of solid pancreatic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:732-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kitano M, Yamashita Y, Kamata K, Ang TL, Imazu H, Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Fusaroli P, Seo DW, Napoléon B, Teoh AYB, Kim TH, Dietrich CF, Wang HP, Kudo M; Working group for the International Consensus Guidelines for Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasound. The Asian Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (AFSUMB) Guidelines for Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021;47:1433-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nayak HK, Rai A, Gupta S, Prakash JH, Patra S, Panigrahi C, Patel RK, Pattnaik B, Kar M, Panigrahi MK, Samal SC. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) elastography-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) versus conventional EUS FNAC for solid pancreatic lesions: A pilot randomized trial. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Manrai M, Tilak TVSVGK, Dawra S, Srivastava S, Singh A. Current and emerging therapeutic strategies in pancreatic cancer: Challenges and opportunities. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:6572-6589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ozono Y, Kawakami H, Uchiyama N, Hatada H, Ogawa S. Current status and issues in genomic analysis using EUS-FNA/FNB specimens in hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancers. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:1081-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dawwas MF, Taha H, Leeds JS, Nayar MK, Oppong KW. Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative EUS elastography for discriminating malignant from benign solid pancreatic masses: a prospective, single-center study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:953-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Otsuka Y, Kamata K, Kudo M. Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Puncture for the Patients with Pancreatic Masses. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chou YH, Liang JD, Wang SY, Hsu SJ, Hu JT, Yang SS, Wang HK, Lee TY, Tiu CM. Safety of Perfluorobutane (Sonazoid) in Characterizing Focal Liver Lesions. J Med Ultrasound. 2019;27:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |