Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100950

Revised: November 21, 2024

Accepted: December 9, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 187 Days and 6.2 Hours

Migraine has been proposed as a potential contributing factor to ischemic compli

To evaluate macular and peripapillary structural and microvasculature changes in patients with migraine with aura (MA), migraine without aura (MW), and healthy control (HC) participants using OCTA.

In this observational cross-sectional study, we studied a total of 100 eyes: (1) 32 eyes of 16 patients with MA; (2) 36 eyes of 18 patients with MW, recruited based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders; and (3) 32 eyes of 16 age and sex-matched healthy participants. Foveal flux, foveal avascular zone (FAZ), peripapillary flux obtained from OCTA, and foveal and peripapillary ganglion cell layer (GCL) thickness calculated via optical coherence tomography were compared among the groups.

The mean FAZ area measured in patients with MA and MW was significantly larger than that in the control participants (P = 0.002). However, there was no significant difference between the FAZ of the MA and MW groups. Macular perfusion in the superficial capillary plexus in patients with MA was significantly lower compared to MW (P = 0.0018) and HCs (P = 0.002). There was also significant thinning of the GCL in patients with MA and MW (P = 0.001) compared to HCs. However, there was no significant difference in temporal GCL thickness between the MA and MW groups.

Significant changes have been found in structural and microvascular parameters in patients with migraines compared with HCs. OCTA can serve as a valuable non-invasive imaging technique for identifying microcirculatory disturbances, aiding in better understanding the pathogenesis of different types of migraine and establishing their link with other ischemic retinal and systemic pathologies.

Core Tip: Our observational study shows that there are microvascular and structural changes seen on optical coherence tomography angiography in migraine, and these changes could serve as a valuable non-invasive biomarker in its diagnosis.

- Citation: Shah P, Shah VM, Saravanan VR, Kumar K, Narendran S. Evaluation of macular and peripapillary structure and microvasculature with optical coherence tomography angiography in migraine in the Indian population. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 100950

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/100950.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100950

Migraine, ranked as the third most prevalent disease worldwide, has an overall prevalence of 14.7% (18.8% in females and 10.7% in males)[1]. The term 'migraine' originates from the Latin word 'hemicrania,' signifying 'half skull.' This designation was initially used by the Greek physician Galenus of Pergamon[2]. Migraine auras refer to sensory symptoms (neurologic, gastrointestinal, and autonomic) that may manifest before or during a migraine attack. These symptoms include phenomena such as light flashes, blind spots, or tingling in the hands or face[2]. Their usual duration spans from 4 hours to 72 hours, and often cause significant incapacitation. These manifestations can occur episodically (fewer than 15 days per month) or chronically (more than 15 days per month). Among migraine headache sufferers, 70% experience migraine without aura (MW)[2]. While the complete pathophysiology of migraine remains elusive, there appears to be a complex interplay between neural and vascular factors that play a pivotal role[3].

For years, migraine has been proposed as a potential contributing factor to ischemic complications involving the retina and optic nerve[4]. Ophthalmic disorders associated with migraine include occlusions of the branch and central retinal arteries and veins, as well as anterior and posterior ischemic optic neuropathy[5]. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that migraine could increase the risk of onset or progression of normal tension glaucoma[6,7]. These disorders have been observed during both acute migraine attacks and the periods between attacks[8]. Consequently, both immediate and sustained alterations in ocular perfusion among patients with migraine might make them more susceptible to the aforementioned ocular complications[8,9].

There have been studies from Turkey and the United States describing optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT angiography (OCTA) parameters among patients with migraine[10], revealing numerous vascular differences compared to the healthy population[11-15]. Nonetheless, there is little literature available on the structural and microvascular parameters of the macula and peripapillary area among the Indian population.

In this study, we investigated the following parameters: (1) Foveal flux as a measure of foveal vasculature (flux is a novel metric that approximates the number of red blood cells moving through vessel segments per unit area); and (2) Foveal avascular zone (FAZ), peripapillary flux in the superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal quadrants through OCTA, and ganglion cell layer thickness (GCL) at the macula and in the superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal peripapillary quadrants as structural parameters through OCT. This study aimed to better understand the differences among three groups: patients with migraine with aura (MA), without aura (MW), and healthy controls (HCs).

After approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of our institute (Project No. RES2023067CLI), we prospectively studied a total of 100 eyes: (1) 32 eyes from 16 patients with MA; (2) 36 eyes from 18 patients with MW; and (3) 32 eyes from 16 HCs. We assessed distant and near visual acuity, refractive error, slit-lamp anterior segment evaluation, posterior segment evaluation by indirect ophthalmoscopy, intraocular pressure by applanation tonometry, and OCT and OCTA parameters, as previously discussed. Patients were selected from the outpatient clinic of the neuro-ophthalmology department of our institute and those referred by neurologists, with inclusion based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition[14]. Exclusion criteria for all groups included any neurologic disorder other than migraine (including neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease); any optic nerve disorders such as glaucoma, ischemic optic neuropathy, or retinal diseases; a history of intraocular surgery other than cataract extraction; systemic conditions affecting the microvasculature such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, vasculitis, or renal disease; and ocular media opacity precluding high-quality imaging. HCs were also excluded if taking vasoactive medications, such as calcium channel blockers. The demographic parameters of participants are described in Table 1.

| Group | Mean age in years | Male | Female | Mean refraction (spherical) | Mean refraction (cylinder) | Mean intraocular pressure |

| Migraine with aura (n = 16) | 28.18 ± 7.23 | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 0.71 ± 0.67 | 0.31 ± 0.36 | 15.25 ± 2.87 |

| Migraine without aura (n = 18) | 28.94 ± 5.95 | 8 (44.44) | 10 (55.55) | 0.47 ± 0.48 | 0.20 ± 0.24 | 15.18 ± 2.58 |

| Healthy controls (n = 16) | 27.875 ± 6.97 | 7 (43.75) | 9 (56.25) | 0.27 ± 0.36 | 0.18 ± 0.26 | 15.82 ± 2.88 |

OCTA images were acquired using the AngioPlex matrix software on the CIRRUS HD-OCT Model 6000© 2021 (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA, United States). The scanning area captured consisted of a 6 mm × 6 mm section centered on the fovea, a 4.5 mm × 4.5 mm section centered on the optic nerve head (ONH), and a 200 µm × 200 µm optic disc cube. The superficial retinal capillary plexus (SCP) was segmented with an inner boundary 3 µm posterior to the internal limiting membrane (ILM) and an outer boundary 15 µm posterior to the outer aspect of the inner plexiform layer. Optic nerve scans were segmented into ONH and radial peripapillary capillary (RPC) slabs. The ONH slab was segmented with an inner boundary at the anterior border of the ILM and an outer boundary 150 µm posterior to the ILM. The software automatically assigned two concentric circles centered at the fovea and ONH. The radii of the inner and outer circles were 1 mm and 2 mm, respectively, providing a ring width of 1 mm. The flux, as a measure of vascularity, of the macular and RPC was evaluated between these rings in the peripapillary region and in four sectors (superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal) around the ONH. The segmentation was between the ILM and the posterior limit of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL). Color-encoded slabs representing different layers were generated. The FAZ area was directly measured with AngioPlex software using a slab from the ILM to 75 µm above the retinal pigment epithelium. CIRRUS 6000 automatically centers and optimizes B-scan settings. The device also automatically corrects for the patient’s refractive error and balances fundus brightness and contrast. Eye tracking was done using FastTrac™.

The macular and peripapillary GCL thickness was also evaluated in the peripapillary region and in four sectors using the same ONH analysis software. OCTA scans with low-quality or inadequate signal strength index (less than 6 on a 10-point scale) were excluded. Scans with blink artifacts, motion artifacts, media opacities interfering with the vessel signals, or segmentation errors were not included in the study.

Age, sex, intraocular pressure, refractive errors, and OCT and OCTA parameters were compared among the three groups: (1) MA; (2) MW; and (3) HCs. An independent t-test was used to test the significant difference between the means of two independent groups. Analysis of variance was used to determine whether the difference between group means (more than two groups) was statistically significant. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 32 eyes from 16 patients in the MA group, 36 eyes from 18 patients in the MW group, and 32 eyes from 16 healthy participants were enrolled. The mean ages for the three groups were as follows. (1) The MA group had a mean age of 28.18 years ± 7.23 years; (2) The MW group had a mean age of 28.94 years ± 5.95 years; and (3) The HC group had a mean age of 27.87 years ± 6.97 years. Across the three groups, the distribution of sexes was similar. In the MA group, 37.5% were male and 62.5% were female; in the MW group, 44.44% were male and 55.56% were female; and in the HC group, 43.75% were male and 56.25% were female. The age (P = 0.89) and sex (P = 0.92) differences were not significant among the groups. Additionally, the intraocular pressure (P = 0.92) and mean refractive errors (0.55) were not significantly different among the groups, as described in Table 1.

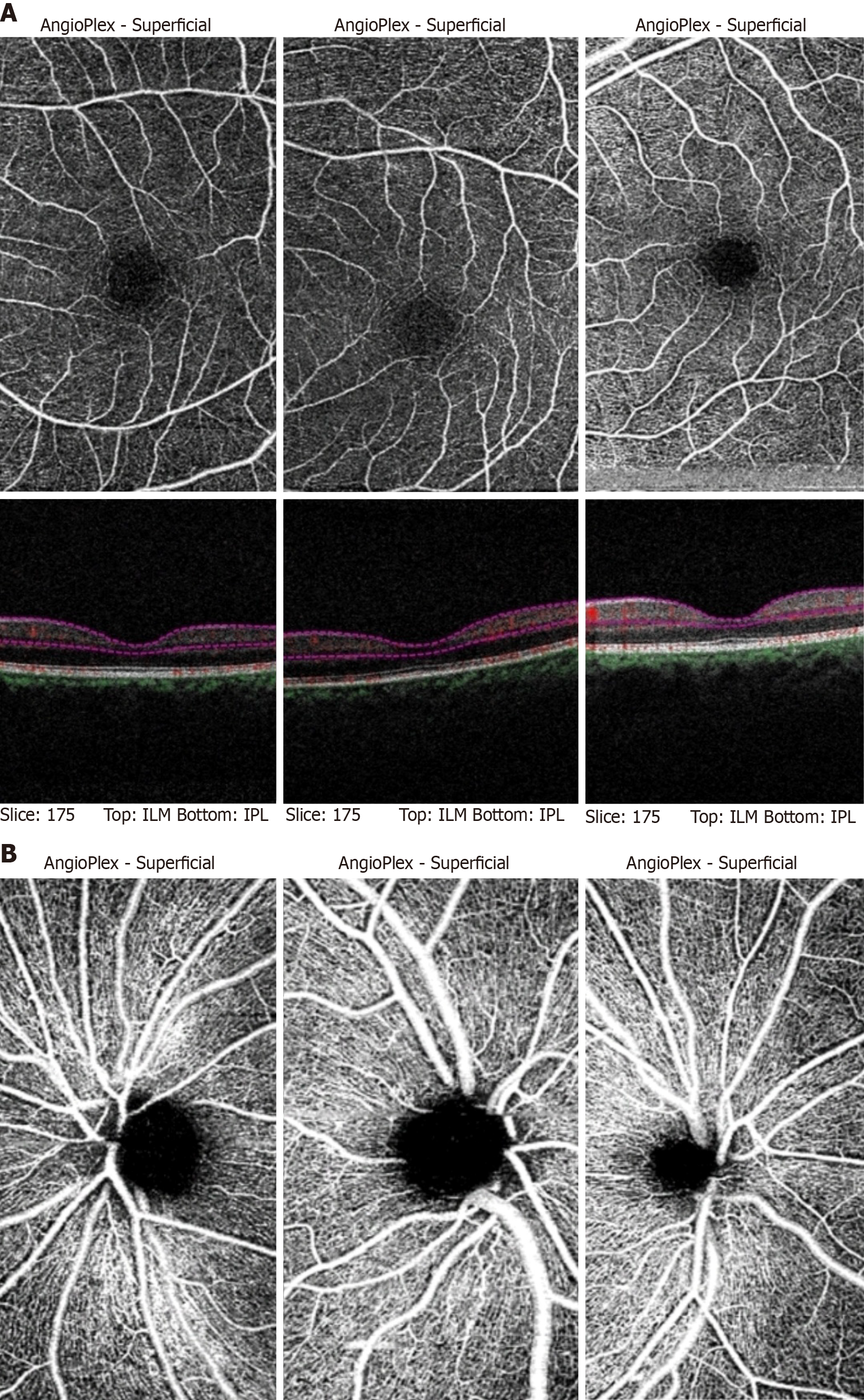

All patients enrolled in the study had a best-corrected visual acuity of 6/6 by distance Snellen's chart and near acuity of N6 by the Jaeger chart. Representative OCTA scans of the MA, MW, and HC participants are shown in Figure 1A (macula) and Figure 1B (optic nerve). Quantitative analysis of macular OCTA findings in the patients with MA and MW, and HCs is shown in Table 2. The mean FAZ area measured 0.34 mm² ± 0.12 mm² in the patients with MA, which was significantly larger than that in the control participants (0.201 mm² ± 0.007 mm²; P = 0.002). The FAZ of patients with MW (0.29 mm² ± 0.14 mm²) was also significantly larger than that in the HCs (P = 0.007). However, there was no significant difference between the FAZ areas of the MA and MW groups.

| Optical coherence tomography angiography parameters | Migraine with aura | Migraine without aura | Healthy controls |

| Foveal flux | 4.16 ± 1.47 | 6.21 ± 3.10 | 6.18 ± 2.12 |

| Foveal avascular zone | 0.34 ± 0.12 | 0.29 ± 0.14 | 0.20 ± 0.07 |

| Superior peripapillary flux | 18.57 ± 4.70 | 19.03 ± 0.93 | 18.69 ± 3.46 |

| Inferior peripapillary flux | 18.22 ± 1.84 | 18.49 ± 1.12 | 18.65 ± 1.25 |

| Nasal peripapillary flux | 17.88 ± 1.69 | 17.14 ± 3.96 | 17.76 ± 2.08 |

| Temporal peripapillary flux | 17.55 ± 1.81 | 22.51 ± 1.83 | 18.71 ± 1.42 |

Macular perfusion in the SCP was significantly lower in patients with MA (4.16 ± 1.47) compared to those with MW (6.21 ± 3.10; P = 0.0018) and HCs (6.18 ± 2.12; P = 0.002). There was no difference in foveal perfusion between the MW and HC groups. There were no significant differences in peripapillary perfusion in the superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal quadrants among the MA, MW, and HC groups, as shown in Table 2.

When comparing structural parameters obtained from OCT, no statistical differences were found in GCL thickness among the MA, MW, and HC groups in the foveal, superior, inferior, and nasal peripapillary regions. However, there was significant thinning of the GCL in patients with MA (29.43 ± 4.01; P = 0.001) compared to HC participants (30.59 ± 3.44). Additionally, the temporal GCL thickness in patients with MW (27.38 ± 3.76; P = 0.009) was significantly reduced compared to HC participants. However, there was no significant difference in temporal GCL thickness between the MA and MW groups.

After analyzing a total of 100 eyes divided into three groups (MA, MW, and HCs), we concluded that the FAZ was enlarged in patients with migraine, both with and without aura, compared to HCs. Microvascular ischemic events or capillary remodeling of near-normal FAZ may be the cause of FAZ enlargement. The FAZ area is reportedly associated with the severity of systemic diseases, such as diabetes, and some studies have indicated that screening for FAZ might help detect early microvascular abnormalities. OCT parameters of MA, MW, and HC are shown in Table 3.

| Optical coherence tomography parameters | Migraine with aura | Migraine without aura | Healthy controls |

| Macular GCL thickness | 9.46 ± 2.25 | 9.25 ± 2.27 | 10.15 ± 3.44 |

| Superior GCL | 29.43 ± 3.76 | 28.58 ± 3.78 | 30.68 ± 3.16 |

| Inferior GCL | 29.40 ± 4.22 | 29.30 ± 4.02 | 29.06 ± 3.59 |

| Nasal GCL | 29.43 ± 4.01 | 28.11 ± 3.59 | 28.75 ± 3.75 |

| Temporal GCL | 29.43 ± 4.01 | 27.38 ± 3.76 | 30.59 ± 3.44 |

Enlarged FAZ has also been observed in several studies conducted in Turkey and the United States[13,15]. Our finding of an enlarged FAZ in patients with MW compared to HCs was supported by the results of Hamurcu et al[16] and Taşlı and Ersoy[17].

Another important conclusion of our study was the reduced foveal vascularity in the SCP in patients with MA compared to patients with MW and HCs. Similar findings have been reported by various studies[13,15,18,19]. The decreased foveal vessel density in the SCP in patients with MA is supportive of retinal microvascular disease. The chronic retinovascular alterations demonstrated by OCTA in patients with MA may be related to the increased risk of ocular complications in patients with migraine, even in the absence of an acute attack[13]. Since the advent of modern techniques, many studies have used various parameters to assess retinal vasculature to establish a link between migraine and other ischemic ocular and systemic diseases. Acer et al[20] reported that ocular pulse amplitude did not significantly differ between patients with migraine without aura and control cases. We employed foveal flux, a novel metric that approximates the number of red blood cells moving through vessel segments per unit area. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that foveal flux is not only a complementary parameter to conventional vessel density but also a potentially useful measure of retinal perfusion, in addition to other OCTA-derived parameters.

We did not find any significant difference in peripapillary vasculature among the three groups. However, the temporal GCL thickness in patients with MA and MW was found to be significantly reduced compared to the HC group. Similar thinning of the GCC and RNFL has been documented in various studies[11,12]. Compromised choroidal blood flow can lead to focal ischemic damage in the optic disc[21]. These structural changes might provide insights into the association of migraine with optic nerve diseases such as anterior and posterior ischemic optic neuropathy, normal tension glaucoma, and others[5,6]. Amaurosis fugax in migraineurs has been proposed as a sign of affected choroidal blood flow[22].

Although most studies have shown more structural and microvascular changes in patients with aura compared to those with MW, we found in our study that FAZ enlargement and temporal GCL thinning were equally significant in patients with MW. Thus, we conclude that all patients with migraine, including those with and without aura, exhibit vascular and structural abnormalities compared to healthy eyes. Although the exact pathogenesis of migraine is still unknown, it is believed to be triggered by specific vessels and nerves in the brain. As the eye is an extension of the brain, these features could be reflected in the retinal blood vessels and nerves as observed by OCTA. Enlargement of the FAZ and loss of GCL could be early changes in migraine cases and may serve as potential biomarkers in the future.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to employ OCT and OCTA parameters in three groups—MA, MW, and HC—to study structural and vascular changes in migraine within the Indian population.

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size was small, which might have contributed to the lack of significant results for some parameters. Additionally, most participants were in the interictal period, so vascular findings during an acute migraine attack could not be assessed. We also failed to include vascularity measures in the deep capillary plexus at the fovea and ONH, thus limiting access to important information. A possible confounding factor could have been the duration of migraine symptoms, as structural changes are chronic phenomena that we did not consider. Finally, migraine is a heterogeneous disorder, making it difficult to categorize patients into distinct groups.

In conclusion, we found significant FAZ enlargement in patients with migraine, both with and without aura, compared to HCs. Additionally, we observed reduced foveal vascularity in patients with aura compared to patients without aura and HCs. These microvascular changes can help establish a link between migraines and other retinal and choroidal ischemic diseases, providing a better understanding of migraine’s lesser-established pathophysiology. We also found temporal GCL thinning in both groups of patients with migraine compared to HC. Repeated insults due to reduced blood supply during attacks may explain these structural changes even during attack-free periods.

Having conducted a study involving 100 eyes across three groups—MA, MW, and HC—we can now consider the future prospects of our research. Building on this pilot study, there is potential to conduct extensive longitudinal investigations. This broader research could encompass factors such as the duration of migraine episodes, acquiring scans during the attack phase, and incorporating a more comprehensive array of parameters.

| 1. | Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez MG, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bernabé E, Bhalla K, Bhandari B, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Black JA, Blencowe H, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Bonaventure A, Boufous S, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Braithwaite T, Brayne C, Bridgett L, Brooker S, Brooks P, Brugha TS, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Buckle G, Budke CM, Burch M, Burney P, Burstein R, Calabria B, Campbell B, Canter CE, Carabin H, Carapetis J, Carmona L, Cella C, Charlson F, Chen H, Cheng AT, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahiya M, Dahodwala N, Damsere-Derry J, Danaei G, Davis A, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Dellavalle R, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dherani M, Diaz-Torne C, Dolk H, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Edmond K, Elbaz A, Ali SE, Erskine H, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ewoigbokhan SE, Farzadfar F, Feigin V, Felson DT, Ferrari A, Ferri CP, Fèvre EM, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Flood L, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Franklin R, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabbe BJ, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Ganatra HA, Garcia B, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gmel G, Gosselin R, Grainger R, Groeger J, Guillemin F, Gunnell D, Gupta R, Haagsma J, Hagan H, Halasa YA, Hall W, Haring D, Haro JM, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Higashi H, Hill C, Hoen B, Hoffman H, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Huang JJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jarvis D, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Jonas JB, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Keren A, Khoo JP, King CH, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Lalloo R, Laslett LL, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Lee YY, Leigh J, Lim SS, Limb E, Lin JK, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Liu W, Loane M, Ohno SL, Lyons R, Ma J, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Manivannan S, Marcenes W, March L, Margolis DJ, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGill N, McGrath J, Medina-Mora ME, Meltzer M, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Meyer AC, Miglioli V, Miller M, Miller TR, Mitchell PB, Mocumbi AO, Moffitt TE, Mokdad AA, Monasta L, Montico M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moran A, Morawska L, Mori R, Murdoch ME, Mwaniki MK, Naidoo K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KM, Nelson PK, Nelson RG, Nevitt MC, Newton CR, Nolte S, Norman P, Norman R, O'Donnell M, O'Hanlon S, Olives C, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Page A, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Patten SB, Pearce N, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Phillips D, Phillips MR, Pierce K, Pion S, Polanczyk GV, Polinder S, Pope CA 3rd, Popova S, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Prince M, Pullan RL, Ramaiah KD, Ranganathan D, Razavi H, Regan M, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Richardson K, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, De Leòn FR, Ronfani L, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Saha S, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Segui-Gomez M, Shahraz S, Shepard DS, Shin H, Shivakoti R, Singh D, Singh GM, Singh JA, Singleton J, Sleet DA, Sliwa K, Smith E, Smith JL, Stapelberg NJ, Steer A, Steiner T, Stolk WA, Stovner LJ, Sudfeld C, Syed S, Tamburlini G, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Taylor JA, Taylor WJ, Thomas B, Thomson WM, Thurston GD, Tleyjeh IM, Tonelli M, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Tsilimbaris MK, Ubeda C, Undurraga EA, van der Werf MJ, van Os J, Vavilala MS, Venketasubramanian N, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weatherall DJ, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Weisskopf MG, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams SR, Witt E, Wolfe F, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh PH, Zaidi AK, Zheng ZJ, Zonies D, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163-2196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5305] [Cited by in RCA: 5779] [Article Influence: 444.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shankar Kikkeri N, Nagalli S. Migraine With Aura. 2024 Feb 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Jacobs B, Dussor G. Neurovascular contributions to migraine: Moving beyond vasodilation. Neuroscience. 2016;338:130-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Beversdorf D, Stommel E, Allen C, Stevens R, Lessell S. Recurrent branch retinal infarcts in association with migraine. Headache. 1997;37:396-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee AG, Brazis PW, Miller NR. Posterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with migraine. Headache. 1996;36:506-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Drance S, Anderson DR, Schulzer M; Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Risk factors for progression of visual field abnormalities in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:699-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 518] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Coppeto JR, Lessell S, Sciarra R, Bear L. Vascular retinopathy in migraine. Neurology. 1986;36:267-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Greven CM, Slusher MM, Weaver RG. Retinal arterial occlusions in young adults. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:776-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chaliha DR, Vaccarezza M, Charng J, Chen FK, Lim A, Drummond P, Takechi R, Lam V, Dhaliwal SS, Mamo JCL. Using optical coherence tomography and optical coherence tomography angiography to delineate neurovascular homeostasis in migraine: a review. Front Neurosci. 2024;18:1376282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ekinci M, Ceylan E, Cağatay HH, Keleş S, Hüseyinoğlu N, Tanyildiz B, Cakici O, Kartal B. Retinal nerve fibre layer, ganglion cell layer and choroid thinning in migraine with aura. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Demircan S, Ataş M, Arık Yüksel S, Ulusoy MD, Yuvacı İ, Arifoğlu HB, Başkan B, Zararsız G. The impact of migraine on posterior ocular structures. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:868967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chang MY, Phasukkijwatana N, Garrity S, Pineles SL, Rahimi M, Sarraf D, Johnston M, Charles A, Arnold AC. Foveal and Peripapillary Vascular Decrement in Migraine With Aura Demonstrated by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:5477-5484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5134] [Cited by in RCA: 5447] [Article Influence: 495.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu Z, Jie C, Wang J, Hou X, Zhang W, Wang J, Deng Y, Li Y. Retina and microvascular alterations in migraine: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1241778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hamurcu MS, Gultekin BP, Koca S, Ece SD. Evaluation of migraine patients with optical coherence tomography angiography. Int Ophthalmol. 2021;41:3929-3933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Taşlı NG, Ersoy A. Altered Macular Vasculature in Migraine Patients without Aura: Is It Associated with Ocular Vasculature and White Matter Hyperintensities? J Ophthalmol. 2020;2020:3412490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Freiberg FJ, Pfau M, Wons J, Wirth MA, Becker MD, Michels S. Optical coherence tomography angiography of the foveal avascular zone in diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:1051-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ulusoy MO, Horasanlı B, Kal A. Retinal vascular density evaluation of migraine patients with and without aura and association with white matter hyperintensities. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119:411-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Acer S, Oğuzhanoğlu A, Çetin EN, Ongun N, Pekel G, Kaşıkçı A, Yağcı R. Ocular pulse amplitude and retina nerve fiber layer thickness in migraine patients without aura. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Flammer J, Pache M, Resink T. Vasospasm, its role in the pathogenesis of diseases with particular reference to the eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:319-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Madill SA. Transient Visual Loss in Young Females with Crowded Optic Discs: A Proposed Aetiology. Neuroophthalmology. 2021;45:372-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |