Published online Sep 20, 2025. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100840

Revised: October 26, 2024

Accepted: December 11, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2025

Processing time: 190 Days and 11 Hours

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe lethal X-linked monogenic recessive congenital muscular dystrophy caused by various types of mutations in the dystrophin gene (DG). It is one of the most common human genetic diseases and the most common type of muscular dystrophy, in part because DG is one of the largest protein-coding genes in the human genome with a relatively high risk of being affected by a large palette of mutations. Long-term corticosteroid therapy (LTCT) with deflazacort started at age 4 is the most accessible and used pharmacological therapy for DMD in Romania. "Asea® redox supplement" (ARS) is an approved dietary supplement in the European Union. Several studies have shown that it is a very potent selective NRF2 activator, and thus a very potent, albeit indirect, antioxidant, with no toxicity up to high doses, in contrast to LTCT.

This paper presents a 3-case series on the effects of ARS in a 4-year-old, 5-year-old and 3-year-old boy all with DMD from Bucharest or Slobozia (Romania). This is the first report of this type worldwide. The parents of these boys had refused LTCT. They were treated with relatively high doses of ARS (3-7 mL/kg/day). For two patients, ARS was administered in combination with medium doses of L-carnitine and omega-3 fatty acids for various intellectual disabilities. Periodic consults and assessments for rhabdomyolysis, medullar and liver toxicity markers (blood count, gamma-glutamyl transferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase, lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase, creatine kinase-MB and serum myoglobin) were performed. In vitro studies showed that ARS is a very potent and selective NRF2 activator, and thus a very potent indirect antioxidant. The in vivo studies also support this main pharmacological mechanism of ARS, with no toxicity at high doses, in contrast with much more toxic corticosteroids which are often refused by parents for their children with DMD. Although they were three distinct ages and carried three distinct DG mutations, from the first months of ARS-based treatment, the children responded similarly to ARS. The rhabdomyolysis markers, which were initially very high, significantly dropped, and there was no evidence for medullar and/or hepatic toxicity in any of the 3 patients.

ARS has significant indirect antioxidant effects via NRF2 and deserves extensive trials in children with DMD, as an adjuvant to corticoids or as a substitute in DMD patients who refuse corticoids. Future trials should also focus on ARS as an adjuvant in many types of acute/chronic infectious/non-infectious diseases where cellular oxidative stress is involved.

Core Tip: Asea redox supplement has significant indirect antioxidant effects via NRF2. Based on the case studies here, extensive trials should be initiated in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) as an adjuvant to corticoids or as a substitute in DMD patients who refuse corticoids. Because of its antioxidant effects, it should also be studied as an adjuvant in many types of acute/chronic infectious/non-infectious diseases in which cellular oxidative stress is involved.

- Citation: Drăgoi AL, Nemeș RM. The remarkable effects of the ionized medical water Asea® in 3 boys with Duchenne dystrophy: Three case reports. World J Methodol 2025; 15(3): 100840

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v15/i3/100840.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v15.i3.100840

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked monogenic muscular dystrophy primarily affecting boys. It is caused by various types of mutations in the dystrophin (DG) gene, one of the longest human genes. It is the most common type of muscular dystrophy, affecting approximately 1/5000 males at birth. Approximately 1/3 of the DMD cases are caused by spontaneous mutations in DG after fertilization, with no family history of DMD. DMD is usually clinically asymptomatic in the first 1-3 years of life. However, routine rhabdomyolysis screening at birth may show increased transaminases [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT)] and creatine kinase (CK) serum levels, as in the case of one of the patients presented in this paper. He presented with increased serum CK levels at birth, though the neonatologist did not refer the parents for additional investigations in a pediatric or neurological service. Therefore, DMD was detected and diagnosed much later for this patient, at age 2.

Various muscular deficits may appear in DMD patients between 3-4 years of age. They typically first occur in the femoral and pelvic muscular groups, and then in the axial muscular groups and may significantly worsen in the next years, progressively affecting the capacity of standing and walking. Most patients with DMD lose ambulation at around 12 years of age. The average life span of DMD patients is approximately 26 years. Some DMD patients are also mentally affected, demonstrating language development delay, an intelligence quotient below average, etc. The exact mechanism by which DG mutations affect neurons is unknown.

Long-term corticosteroid therapy (LTCT) with deflazacort is the first line treatment for DMD. LTCT is started at age 4, as it was clearly demonstrated to decrease chronic muscular inflammation (CMI) and slow the progressive muscular fibrosis in DMD patients. In addition, LTCT induces the expression of utrophin, a cytoskeletal protein homologous to dystrophin that can partially compensate for the lack of normal dystrophin in the affected muscular fibers of DMD patients. There have been calls to start LTCT earlier. However, many Romanian parents refuse LTCT for their DMD children because of the large spectrum of adverse effects of LTCT. The genetic therapies of DMD attempt to sidestep the DG mutation by exon skipping or to correct the DG mutation by CRISPR: While they have shown some promise, they are still under investigations and inaccessible in Romania.

Nuclear factor (Erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NFE2 L2 or NRF2) is a transcription factor that governs phase II of the cellular stress response by activating over 150 genes coding various proteins, especially endogenous antioxidant enzymes (EAEs) like glutathione synthase, glutathione peroxidases, superoxide dismutase, and catalase. EAEs are mainly activated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neutralize those ROS. Physical effort constantly generates ROS, primarily superoxides, which then stimulate the production of EAEs via NRF2 activation. This is a well-known essential process for cell survival and viability called “oxidative eustress”, which also explains why physical therapy significantly helps DMD patients. By also activating tissular lipases, NRF2 partially switches glucose metabolism to lipid metabolism, increasing cellular energy production. NRF2 has higher cellular cytoplasmatic concentrations in the kidneys, muscles and lungs, compared to lower cytoplasmatic concentrations in the heart, liver and brain.

There are many known NRF2 activators, both allopathic (monomethyl and dimethyl fumarate, hyperbaric oxygen, some NSAIDs)[1] and natural (sulforaphane, alpha-lipoic acid, curcumin, polyphenols like quercetin and resveratrol, ginseng plant extract, ginkgo biloba tree extract, oxidative eustress via physical effort, caloric restriction, sleep, etc).

Asea redox supplement (ARS) is a superoxide-based ionized medical water. Very low non-toxic concentrations of superoxides are the main ingredient of ARS and the most potent NRF2 activator from its composition, with sufficient oral bioavailability to produce notable biological effects measured both in vitro[2] and in vivo[3,4]. Studies on ARS so far, including studies on “MDI-P”, the former name for ARS[2], are very encouraging and motivate in-depth future research on the biological and therapeutic effects of ARS in both healthy or ill adults and children with various pathologies. There was also a clinical trial on ARS organized in 2013 and called “Effect of ASEA on Energy Expenditure and Fat Oxidation in Humans”, but the results of this trial have not yet been published online for unknown reasons[3].

ARS is at the bridge between allopathic and natural NRF2 activators because it contains many types of ROS (mainly superoxides) and reductive species artificially produced by patented multi-stage electrolysis and stabilized by a special method, which are also naturally produced by all animal cells, including human.

In vitro studies demonstrated that ARS is a dietary supplement (approved in both the United States and European Union) with strong selective NRF2-activating properties. It is significantly “stronger” than sulforaphane, which is the most potent natural NRF2-activator known until present. Therefore, it also acts as a very potent indirect antioxidant by increasing the cellular concentrations of EAEs. In vivo studies also support the non-toxic NRF2-activating properties of ARS.

An initial double-blind randomized trial of metabolomics from 2010 on the effects of ARS consumption in athletes [4] demonstrated a spectacular increase in the serum levels of many fatty acids compared to a placebo group. The fatty acids are mobilized from the body's own adipose tissue, most likely by activating tissular lipases via NRF2, leading to a higher lipidic catabolic rate, increasing the capacity for physical effort. ARS also induced a remarkable increase in serum vitamin C levels by mobilizing it from hepatic reserves and thus increasing the blood antioxidant capacity of those tested.

Another very interesting study demonstrated that ARS can activate several genes, most likely via NRF2. The target genes are involved in activation of some important physiological mechanisms, including: (1) Innate immune mechanisms; (2) Some vascular regeneration systems (also involved in maintaining vascular elasticity); (3) Digestive enzymatic systems (which increase digestion efficiency); (4) Hormonal pathways; and (5) Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory mechanisms, which are also involved in immune tolerance[5].

This paper presents a series of 3 pediatric clinical DMD cases treated by using a combination of ARS, L-carnitine and omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids) as an adjunctive treatment, mainly because the parents of these boys firmly refused LTCT for various reasons, although it was proposed to them by the attending neurologists, including the pediatrician author. The main clinical and paraclinical data of patients are summarized below.

Case 1: This 2-year-and-8-month-old boy (initial age when he entered this study) was diagnosed with DMD at 1-year-and-4-months. His parent refused kinesiotherapy, rejected LTCT in advance and requested for an adjuvant/LTCT replacement long before he reached 4 years of age.

Case 2: This 4-year-and-8-month-old boy (initial age when he entered this study) was diagnosed with DMD at 2-years-and-11-months, but his parents rejected LTCT and requested an adjuvant/LTCT replacement.

Case 3: This 3-year-old boy (initial age when he entered this study) was diagnosed with DMD at 2-years-and-9-months, but his parents rejected LTCT in advance and requested for an adjuvant/LTCT-replacement long before he reached 4 years of age.

The 3 boys reported here were diagnosed with DMD at relatively young ages between 1 and 3 years-old. All 3 cases were confirmed to have DMD by genetic tests.

Case 1: This patient had a duplication of the 7547th nucleotide in the 52nd exon of DG.

Case 2: This patient had a hemizygous duplication of a block of exons (from the 8th to the 43rd) of DG. This is a rare DG mutation present in only about 5% of all known DMD cases.

Case 3: This patient had a heterozygous complete deletion of the 49th and 50th exons of DG, which is the most frequent type of exon-deletion in DMD.

There were no significant past illness besides DMD, except one urinary tract infection (UTI) episode (case 1) and respiratory failure with marked cyanosis at birth associated with anemia and unrecognized rhabdomyolysis (case 3).

Case 1: The patient had an UTI episode at the age of 1-year with a slightly enlarged left kidney according to the renal ultrasound, which resulted in hospitalization. Suspicion of DMD was first raised due to his increased rhabdomyolysis biomarkers.

Case 2: The patient had no significant history.

Case 3: The patient had a history of prematurity (33 weeks of gestation) caused by a severe episode of pyelonephritis of his mother, who had a history of unilateral kidney stones. His body mass (BM) at birth was 2.15 kg. His Apgar score was 6 due to marked respiratory insufficiency and secondary marked cyanosis and altered state, requiring oxygen therapy at birth. He had a systolic heart murmur (grade III-IV/VI) and anemia at birth (Hgb = 10.5 g/dL), for which he needed a blood transfusion with two units of blood. After transfusion, his hemoglobin increased to Hgb = 12.8 g/dL. He remained in the hospital for about 3 weeks after birth; CK = 2600 U/L (normal range, 0-370 U/L) and AST = 780 U/L at birth (normal range, 0-40 U/L). Despite these increased AST and CK serum levels, the patient was not referred to any neurological and/or infectious diseases consult, nor were CK-MB levels measured. On January 22, 2019, at the age of 2 years and 5 months, a dermatologist performed routine screening on the patient for allergy concerns. Blood tests were run by a private lab in Slobozia and indicated AST = 970 U/L, ALT = 844.5 U/L. He was redirected to the “Victor Babes” Infectious Diseases Hospital in Bucharest. Common hepatic infectious diseases were excluded, and the patient was transferred to the “Victor Gomoiu” Pediatric Hospital on February 27th, 2019 for muscular dystrophy genetic screening.

The most significant data from the family history are two maternal uncles (case 1 and case 3) who were described by the mothers to have typical DMD phenotypes, although they were undiagnosed at that time. They both lost ambulation around age 7 and died around age 20.

Case 1: The patient had a maternal uncle “immobilized in bed” from the age of 7 and who died at the age of 18. This is a classical DMD phenotype, although the boy’s mother said that “her uncle was not diagnosed with Duchenne”.

Case 2: The patient had no significant family history.

Case 3: According to his mother, the patient had a maternal uncle who “walked on his toes until the age of 6-7 years old and lost his capacity to walk at the age of approximately 7 years old and died at the age of 20 years old”, which is a classical DMD phenotype. The boy’s mother had unilateral kidney stone disease complicated with acute pyelonephritis with high fever and severe renal pain in the 33rd week of gestation, which caused premature labor and birth.

All 3 boys from this case series had typical DMD phenotypes when examined physically, mainly with symmetric bilateral pseudohypertrophy of both calves and slight axial hypotonia.

Case 1: The patient had a normal BM of 14 kg (55th percentile), a normal body size of 91cm (30th percentile), a normal cranial circumference of 47cm (10th percentile), an incomplete extension of the right calf especially when walking and running, a symmetric bilateral pseudohypertrophy of both calves (maximum diameter of calves= 23/23 cm), a slight axial muscular tone deficit but absent Gowers’s sign, a tendency for constipation, and a slight delay in language development. He used approximately 20 words, rarely combined into two-word sentences, and rarely used a verb.

Case 2: The patient had a normal BM of 15 kg (25th percentile), a loss of muscular strength predominantly in axial muscles and lower limbs with Gowers’s sign present, pseudohypertrophy of both calves, a North Star Ambulatory Assessment score (January 2018) of 17/34 (half of the maximum score), a 6-minute walk test result (January 2018): 292 m, without any stops or falls and no need for any external physical support during testing, normal cranial nerves, and normal intellect.

Case 3: The patient had a low development quotient = 62% of the normal for age and sex according to the psychologist who evaluated the child at “Victor Gomoiu” Children’s Hospital in Bucharest, a normal BM of 12.5 kg (10th percentile), walked and ran independently but with a slightly enlarged sustaining base, had a slight axial muscular hypotonia with mild kyphosis and lumbar hyperlordosis. He also had slight pseudohypertrophy of the calf muscles (both with 19.5 cm in circumference). The boy did not cooperate during assessment for the Gower’s sign due to marked agitation. He did not have urethral or anal sphincter control, as he did not announce his imminent micturitions and defecations. He had normal cranial nerves and tight phimosis. His mental examination indicated the following. Language: Language development delay with predominant expressive language delay. He used only about five Romanian words; he only used two verbs “give me” (distorted) and “bye”, both correctly used. He did not build simple sentences; he could not combine two or more words. He demonstrated inconsistent visual contact with the examiner and his parents when he was called by name. He could follow simple instructions (to stand on his potty or to take out his pampers by himself alone; he brought and offered various objects at request). He pointed to various objects with his index finger or hand at request; Social skills: He did not get closer to smaller children but he sometimes wanted to socialize with children older than his age; Play skills: He used toys in normal ways. He did not prefer atypical toys (like bottles or laces/cords/strings, leaf, etc); he preferred to play with balls, and also with water.

All 3 DMD patients had significant rhabdomyolysis, which is part of a typical DMD phenotype and its main paraclinical feature.

Case 1: At the age of 2-years-and-8-months (January 16, 2018) he had the following labs before starting ARS (N = Normal/upper limit of the normal range): AST: 473 U/L (about 10 × N); ALT: 558 U/L (about 17 × N); gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT): 10 U/mL (N); CK: 34453 U/L (about 201 × N); CK-MB: 1241 U/L (about 52 × N); myoglobin (MG): 2006 ng/mL (about 28 × N); C-reactive protein: 0.6 mg/L (N); erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 9 mm/h (N); complete blood count (CBC): N.

Case 2: At the age of 6-months-and-3-weeks (October 11, 2014), the patient had the following labs long before starting ARS: AST: 279 U/L (about 6 × N); ALT: 285 U/L (about 9 × N); GGT: 8 U/mL (N); CBC: N. At the age of 2-years-and-8-months (November 2, 2016) he had the following labs long before starting ARS: CK: 27609 U/L (about 161 × N); CK-MB: 704 U/L (about 29 × N); lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): 4572 U/L; GGT: 10 U/mL (N).

Case 3: At the age of 2-years-and-6-months (January 22, 2019), the patient had the following labs long before starting ARS: AST: 970.9 U/L (> 20 × N); ALT: 844.5 U/L (> 20 × N). On January 30, 2019, at his routine hepatitis screening conducted by an infectious disease specialist from the “Victor Babes” Infectious Diseases Hospital from Bucharest), his tests were as follows: Negative B and C hepatitis serologies; negative Toxocara serology; AST: 685 U/L (> 15 × N); ALT: 770 U/L (> 15 × N); GGT: 10 U/L (N); CK: 27 713 U/L (> 200 × N); LDH: 5317 U/L (a non-specific marker for tissular damage, including rhabdomyolysis, especially myocardium damage). On February 27, 2019, during routine DMD screening by a neurologist from the “Victor Gomoiu” Pediatric Hospital, before starting any therapy, his tests were as follows: AST: 860 U/L (> 20 × N); ALT: 770 U/L (> 15 × N); CK: 24000 U/L (> 200 × N); LDH: 3026 U/L. During a routine check with the same neurologist from the “Victor Gomoiu” Pediatric Hospital after the first 3 months of L-carnitine 1 g/day, his test results were as follows: AST: 311 U/L (> 7 × N); ALT: 356 U/L (> 8 × N); CK: 18350 U/L (> 200 × N); LDH: 2670 U/L.

Imaging studies of these 3 DMD-patients, primarily abdominal and cardiac ultrasound, did not provide additional significant insights.

Case 1: Abdominal ultrasound indicated slight hepatomegaly with otherwise normal ultrasound.

Case 2: Heart ultrasound at the age of 3 months indicated a large stenosis of the right pulmonary artery with no hemodynamic significance, and thus no clinical signs.

Case 3: Heart ultrasound (September 28, 2016; at the age of 7 months) indicated the following: Ventricular septal defect with diameters 3/3.6mm (with secondary left-to-right cardiac shunt). The defect spontaneously healed according to the next heart ultrasound performed at the age of 2 years and 7 months. His abdominal ultrasound from the age of 2 years and 5 months was normal.

All the 3 patients were already diagnosed with DMD before the pediatric consult performed by the author of this paper and long before starting the ARS treatment. The various multidisciplinary consults offered to the DMD-patients before starting ARS per oris (/by mouth) were accomplished by general practitioners, neurologists, geneticists, infectious disease specialists, nephrologists and kineto-therapists.

None.

None.

On January 30, 2019, during routine hepatitis screening conducted by an infectious disease specialist from the “Victor Babes” Infectious Diseases Hospital from Bucharest, his test results were as follows: Negative B and C hepatitis serologies; negative Toxocara serology; AST: 685 U/L (> 15 × N); ALT: 770 U/L (> 15 × N); GGT: 10 U/L (N); CK: 27 713 U/L (> 200 × N); LDH: 5317 U/L (a non-specific marker for tissular damage, including rhabdomyolysis, especially myocardium damage). On February 27, 2019 during routine DMD screening conducted by a neurologist from the “Victor Gomoiu” Pediatric Hospital before starting any therapy, his levels were as follows: AST: 860 U/L (> 20 × N); ALT: 770 U/L (> 15 × N); CK: 24 000 U/L (> 200 × N); LDH: 3026 U/L. On a routine check after the first 3 months of treatment with L-carnitine 1 g/day for DMD, conducted by the same neurologist from the “Victor Gomoiu” Pediatric Hospital, his levels were as follows: AST: 311 U/L (> 7 × N); ALT: 356 U/L (> 8 × N); CK: 18 350 U/L (> 200 × N); LDH: 2670 U/L.

All the 3 patients were already diagnosed with DMD long before the pediatric consult by the author of this paper and before starting the ARS treatment.

DMD with typical phenotype.

DMD with typical phenotype.

DMD with typical phenotype.

All 3 DMD patients were prescribed a mix of ARS, L-carnitine and omega-3 fatty acids. Progressively higher doses of ARS were administered, and labs were performed after each increase of the ARS dose.

The initial dose of ARS was 4 mL/kg/day and was progressively increased up to 7.3 mL/kg/day.

The initial dose of ARS was 4 mL/kg/day and was maintained as such throughout the study.

The initial dose of ARS was 2.3 mL/kg/day and was then progressively increased up to 4.6 mL/kg/day.

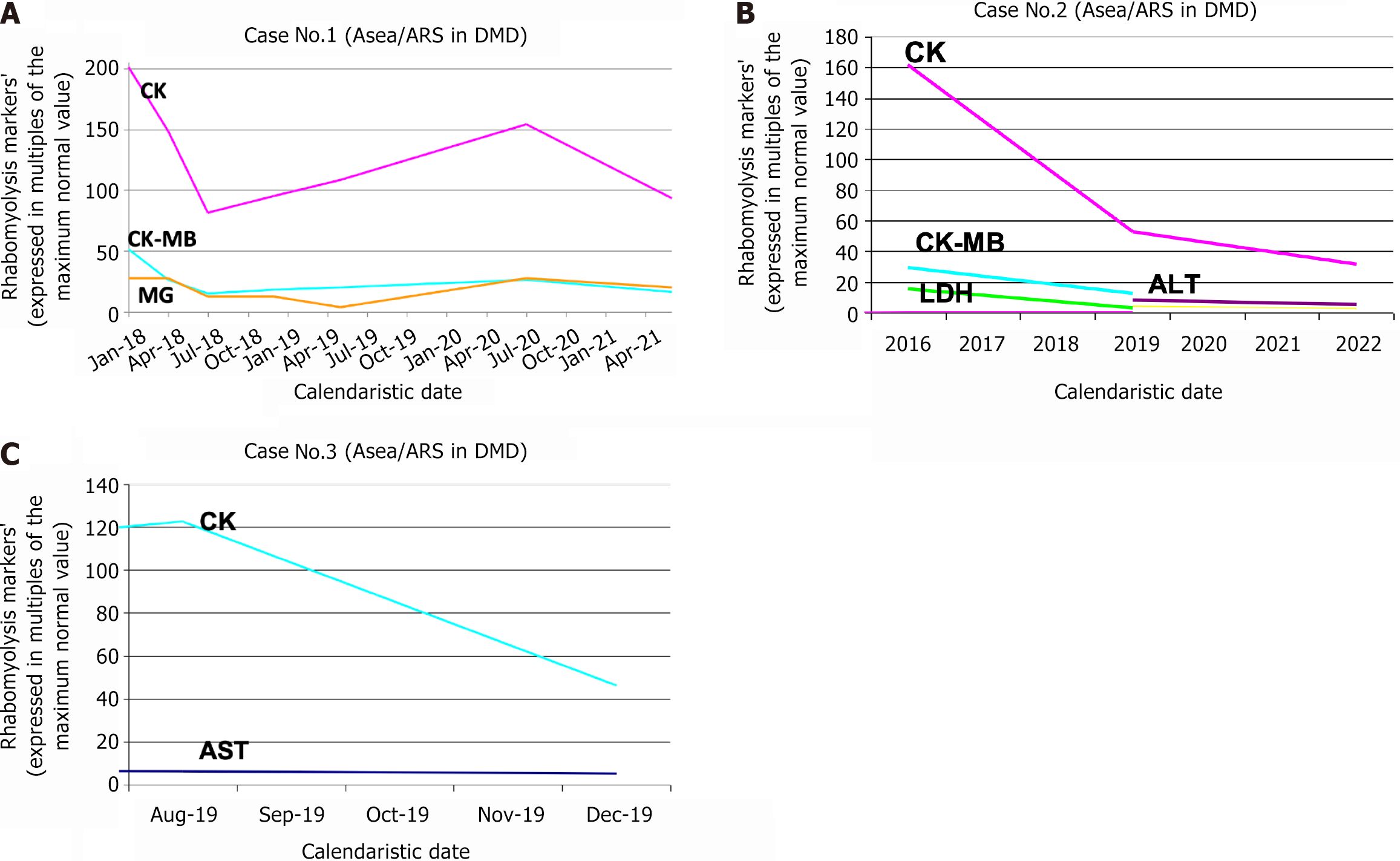

In the next graphs, we present the significant decrease in rhabdomyolysis markers after the introduction of ARS (associated with L-carnitine and omega-3 fatty acids) as an adjuvant treatment of these 3 patients with DMD.

After 6 months of ARS treatment with dose 4-6.5 mL/kg/day, the patient’s results were as follows: Normal BM of 14.2 kg (50th percentile), normal body size of 96.5 cm (50th percentile), a relatively N axial muscular tonus (absent Gowers’s sign), no deficit of right calf extension, no tendency of constipation, clear improvements in language development (he uses approx. 30-40 words; he could imitate over 100 words; he used simple propositions and even short phrases). Notably, the boy’s parents were not compliant in starting physiotherapy for the child. After 11 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4-6.5 mL/kg/day, his results were as follows: A relatively normal-but-under-average BM of 14.2 kg (30th percentile), normal body size of 98 cm (40th percentile), N axial muscular tonus (absent Gowers’s sign), no deficit of right calf extension, a North Star score of 34 (maximum), no tendency for constipation, clear improvements in language development (he used approx. 50-100 words; he could imitate over 150 words; he used propositions and phrases). He also had two successive UTI episodes (empirically treated by the family doctor of the boy, without renal ultrasound, without urine exam nor urinalysis before and/or after antibiotic therapy). Notably, the parents refused referral to nephrological consult for a voiding cystography to exclude vesicoureteral reflux. After 16 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4-6.5 mL/kg/day, his results were as follows: No UTI episodes from the previous consult; normal and above average BM of 15.5 kg (70th percentile), normal body size of 101 cm (50th percentile), N axial muscular tonus (absent Gowers’s sign), no deficit of right calf extension, a North Star score of 34 (maximum), no tendency for constipation, clear improvement in language development (he uses approx. 150-200 words; he can imitate any word; he uses relatively complex propositions and phrases). After 19 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4-7.3 mL/kg/day, he had a 6-minute walking test result of 240 m in 4 minutes (> 50 m/min) because the boy did not cooperate for the full 6 min duration of this test. After 3 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4 mL/kg/day, his lab results were as follows: AST: 453 U/L (about 9 × N); ALT: 712 U/L (about 22 × N); CK: 25 426 U/L (about 149 × N); CK-MB: 632 U/L (about 26 × N). After 6 months of ARS treatment with doses of 6.5 mL/kg/day, his lab results were as follows: AST: 205 U/L (about 5 × N); ALT: 492 U/L (about 12 × N); CK: 13900 U/L (about 70 × N); CK-MB: 365 U/L (about 14 × N); MG: 886 ng/mL (about 12 × N). After 11 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4-6.5 mL/kg/day: AST: 262 U/L (about 6 × N); ALT: 461 U/L (about 12 × N); CK: 16271 U/L (about 81 × N); CK-MB: 437 U/L (about 17 × N); MG: 885 ng/mL (about 12 × N). After 16 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4-6.5 mL/kg/day he had: CK: 18537 U/L (about 92 × N); CK-MB: 486 U/L (about 19 × N); MG: 275 ng/mL (about 4 × N). After 30 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4-5 mL/kg/day he had: CK: 26330 U/L (about 153 × N); CK-MB: 626 U/L (about 26 × N); MG: 1980 ng/mL (about 28 × N). After 41 months of ARS treatment with doses of 4-5 mL/kg/day: CK: 15937 U/L (about 93 × N); CK-MB: 389 U/L (about 16 × N); MG: 1455 ng/mL (about 20 × N) (Figure 1A).

After 7 months of ARS treatment with a dose of 4 mL/kg/day, his test results were as follows: A slight clinical improvement in muscle strength as primarily demonstrated by the 6-minute walk test; the boy had also followed other types of therapy partially initiated by his mother: Physical therapy, hydrotherapy, multivitamins and minerals, acupuncture, homeopathic remedies. The 6-minutes walking test result (July 27, 2019) (under the surveillance of his mother only) was: 359 m in 4 min (> 50 m/min) because the boy would not cooperate for the full 6 min duration of this test. The 6-minutes walking test result (July 29, 2019, under the surveillance of the pediatrician) was 320 m in 6 minutes and 20 seconds (given a fall and a short pause of 20 sec between min 4:18 and 4:38). After 3.5 months of 4 mL/kg/day of ARS treatment, he had: AST: 213 U/L (about 4 × N); ALT: 264 U/L (about 8 × N); CK: 8979 U/L (about 53 × N); CK-MB: 295 U/L (about 7 × N); LDH: 806 U/L; GGT: 10 U/mL (N); anti-streptolysin O: 317 IU/mL; Ferritin: 87 ng/mL. After 3 years and 3 months of 4 mL/kg/day of ARS treatment, he had: AST: 142 U/L (about 3 × N); ALT: 180 U/L (about 6 × N); CK: 5337 U/L (about 31 × N); Ferritin: 47.6 ng/mL (Figure 1B).

After 4 months of ARS treatment at a dose of 2.3 mL/kg/day, he had an improved axial muscular tonus and strength. The boy had become more attentive and was more cooperative with his parents. However, he showed no significant language improvements. After 3 weeks of 2.3 mL/kg/day ARS treatment, he had: AST: 303 U/L (7 × N), ALT: 175 U/L (4 × N), CK: 21000 U/L (4 × N), LDH: 3448 U/L (10 × N). After 4 months of ARS treatment with dose 2.3 mL/kg/day, he had: AST: 241.98 U/L (5 × N), CK: 7885.7 U/L (46 × N), LDH: 1 318.65 U/L (3.8 × N) (Figure 1C).

In vitro studies[6] have clearly demonstrated that ARS is a strong selective NRF2 activator and consequently increases (up to 8-fold) the cellular concentrations of EAEs (like glutathione synthase, SOD etc). In vivo studies also support the NRF2-activating properties of ARS. Therefore, we hypothesize that the significant decrease in measured rhabdomyolysis markers (CK, CK-MB, LDH, AST, ALT) after ARS treatment is due to its potent NRF2-activating mechanism and subsequent activation of EAEs that neutralize a large quantity of ROS from muscle cells, including cardiomyocytes, to decrease the CMI and rhabdomyolysis rate.

Given that the rhabdomyolysis lab tests were all paid by the patients’ parents, and also given the low average monthly income of Romanians, it would have been too expensive to cover the additional labs needed to clearly demonstrate the NRF2-activating effect of ARS in vivo: These tests would have included SOD plasma levels, the total antioxidant capacity of serum, malondialdehyde plasma levels, the intracellular level of the reduced glutathione, among others. The preliminary results on these 3 DMD cases deserve a future grant to extensively study more DMD patients and use an extensive panel of labs that includes antioxidant markers, as also discussed below.

Some rhabdomyolysis markers are missing from the monitoring of these 3 boys with DMD, because the parents did not always collaborate for a complete set of rhabdomyolysis markers, often for objective reasons related to familial financial resources. The previously described positive effects of ARS are plausibly determined via NRF2, by acting on the oxidative-stress link of the DMD pathogenic chain.

It would have been ideal to check both serum and urinary MG levels to exclude the possibility that increased MG excretion caused the observed decreased MG serum levels, rather than an actual decrease in MG production rate by decreased rhabdomyolysis. ARS may activate the cellular excretion pumps via NRF2, allowing for renal excretion of some cellular toxins, as NRF2 expression and activity are increased in kidneys. The concomitant determination of both serum and urinary MG is relatively expensive and inaccessible for the average Romanian patient.

The main explanation of the low number of DMD patients reported here (with no control group) is that DMD is relatively rare and DMD child-patients whose parents refuse corticosteroids but accept ARS as a compensatory adjuvant are very rare in Romania. Furthermore, very few Romanian medical doctors know about ARS and much fewer have experience in prescribing ARS as an adjuvant dietary supplement.

We have given many details and explanations of the adjuvant medication and other non-pharmacological therapies used in all 3 DMD cases. However, we had to synthesize a large quantity of data as not to overwhelm the potential readers with a very large article. Unfortunately, the cited papers on ARS were very difficult to find because many references did not have DOIs, as they were not published in peer-review journals.

Although this report contains only 3 cases, it is invaluable in that we followed these 3 patients for several years (4 years in average). This relatively long time-scale provides an additional argument for the long-term safety of ARS, which is very important for children in general. Furthermore, all 3 cases showed significant decreases in rhabdomyolysis markers, despite the patients having distinct genetic mutations in the DMD gene, indicating that chronic oxidative stress (from the muscular cells of patients with DMD phenotype) is a common physiopathogenic link on which ARS predominantly acts.

These promising preliminary results should be ideally followed by a rigorous randomized double-blind study in which a much larger number of DMD boys are divided into at least four or five groups: (1) A placebo group; (2) A group treated with ARS only; (3) A group treated with L-carnitine only; (4) A group treated with both ARS and L-carnitine simultaneously (given their plausible synergy, as shown in this case series); and (5) A group treated with ARS, L-carnitine and omega-3 fatty acids simultaneously. The initiation of such a large clinical trial would be very costly for Romanian patients without a public or private grant.

Because ARS increases the rate of glutathione-synthesis via NRF2, it is possible that an additional association between ARS and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) would be synergistic, given that NAC is a glutathione precursor.

By reporting and discussing this case series, we re-emphasize the importance of physiopathological reasoning in medical research, as also implemented in the “Electronic pediatrician” software developed by the main author of this paper[7]. An important part of DMD physiopathogenesis is the chronic oxidative stress within skeletal and cardiac muscle fibers that leads to significant CMI and consequent progressive muscular fibrosis. Physiopathological reasoning centered around this chronic oxidative stress inspired the use of NRF2-activating ARS as an adjuvant treatment for these 3 boys with DMD, with encouraging results to date.

ARS has significant indirect antioxidant effects via NRF2 and deserves extensive trials in children with DMD, alone or in combination with L-carnitine and/or omega-3 fatty acids and/or NAC, as an adjuvant to corticoids or as a substitute in DMD patients who refuse corticoids. ARS also deserves future trials as an adjuvant in many types of acute/chronic infectious/non-infectious diseases in which cellular oxidative stress is involved.

| 1. | Eisenstein A, Hilliard BK, Pope SD, Zhang C, Taskar P, Waizman DA, Israni-Winger K, Tian H, Luan HH, Wang A. Activation of the transcription factor NRF2 mediates the anti-inflammatory properties of a subset of over-the-counter and prescription NSAIDs. Immunity. 2022;55:1082-1095.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (142)] |

| 2. | Baltch AL, Smith RP, Franke MA, Ritz WJ, Michelsen P, Bopp LH, Singh JK. Microbicidal activity of MDI-P against Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Legionella pneumophila. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28:251-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (142)] |

| 3. | Effect of ASEA on Energy Expenditure and Fat Oxidation in Humans. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01884727. |

| 4. | Shanely RA, Nieman DC, Henson DA, Knab AM, Cialdella-kam L, Meaney MP, Baxter S, Sha W. Influence of a redox‐signaling supplement on biomarkers of physiological stress in athletes: a metabolomics approach. FASEB J. 2012;26. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ward K. Initial Gene Study Showed ASEA REDOX Affected Important Signaling Pathway Gene. Available from: https://ugc.production.linktr.ee/3ea87dc0-3668-47af-b5c5-4a5fd83d193e_Gene-Study-Actual-Data.pdf. |

| 6. | Samuelson GL. White Paper on In-Vitro Bioactivity of ASEA™ Related to Toxicity, Glutathione Peroxidase, Superoxide Dismutase Efficacy and Related Transcription Factors. Available from: https://www.amazingmolecules.com/pdf/Antioxidant-Efficacy-White-Paper.pdf. |

| 7. | Drăgoi AL. The Remarkable Effects of “ASEA redox Supplement” In A Child with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)-A Case Report. Can J Biomed Res Technol. 2019;1. |