Published online Dec 20, 2023. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v13.i5.475

Peer-review started: September 13, 2023

First decision: October 7, 2023

Revised: October 17, 2023

Accepted: November 3, 2023

Article in press: November 3, 2023

Published online: December 20, 2023

Processing time: 98 Days and 3.7 Hours

Israel has a high rate of Jewish immigration and a high prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

To compare IBD prevalence in first-generation immigrants vs Israel-born Jews.

Patients with a diagnosis of IBD as of June 2020 were included from the validated epi-IIRN (Israeli IBD Research Nucleus) cohort that includes 98% of the Israeli population. We stratified the immigration cohort by IBD risk according to country of origin, time period of immigration, and age group as of June 2020.

A total of 33544 patients were ascertained, of whom 18524 (55%) had Crohn’s disease (CD) and 15020 (45%) had ulcerative colitis (UC); 28394 (85%) were Israel-born and 5150 (15%) were immigrants. UC was more prevalent in immigrants (2717; 53%) than in non-immigrants (12303, 43%, P < 0.001), especially in the < 1990 immigration period. After adjusting for age, longer duration in Israel was associated with a higher point prevalence rate in June 2020 (high-risk origin: Immigration < 1990: 645.9/100000, ≥ 1990: 613.2/100000, P = 0.043; intermediate/low-risk origin: < 1990: 540.5/100000, ≥ 1990: 192.0/100000, P < 0.001). The prevalence was higher in patients immigrating from countries with high risk for IBD (561.4/100000) than those originating from intermediate-/low-risk countries (514.3/100000; P < 0.001); non-immigrant prevalence was 528.9/100000.

Lending support to the environmental effect on IBD etiology, we found that among immigrants to Israel, the prevalence of IBD increased with longer time since immigration, and was related to the risk of IBD in the country of origin. The UC rate was higher than that of CD only in those immigrating in earlier time periods.

Core Tip: In this nationwide study, we compared inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) rates between first-generation immigrants originating from countries of varying IBD risk vs Israel-born residents. Our focus on the Jewish population was aimed at narrowing the genetic variation of IBD that is usually present in immigration cohorts. We found that the prevalence rate was lower among patients from intermediate- and low-risk regions compared to patients from high-risk regions but in both, the prevalence increased in association with duration in Israel after immigration. This finding, especially among immigrants from intermediate- and low-risk countries, lends support toward the role of environmental factors in IBD pathogenesis in Israel.

- Citation: Stulman M, Focht G, Loewenberg Weisband Y, Greenfeld S, Ben Tov A, Ledderman N, Matz E, Paltiel O, Odes S, Dotan I, Benchimol EI, Turner D. Inflammatory bowel disease among first generation immigrants in Israel: A nationwide epi-Israeli Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Nucleus study. World J Methodol 2023; 13(5): 475-483

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v13/i5/475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v13.i5.475

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is rising sharply in low socio-demographic index regions such as Africa, Asia, and South America[1-3]. Increasing rates have also been observed among immigrants from low-resource countries to developed countries[4-6], and to a lesser extent, also vice versa (e.g., from the Faroe Islands to Denmark, where the excess ulcerative colitis (UC) risk in Faroese immigrants was no longer seen after immigration to the new country)[7], implying probable environmental triggers for developing IBD. However, these nationwide studies have included immigrants from various ethnicities[5,8,9] with different genetic backgrounds compared to the host country, hampering attention to the environmental effect on IBD risk. In contrast, in Israel, which is defined as a high prevalence country for IBD, reaching 0.59% of the total population in 2021, and 0.67% among the Jewish population[10,11], the vast majority of immigrants are Jewish or first-degree relatives of Jewish residents who share a similar genetic background[12]. This poses a unique opportunity to study the impact of environmental factors in a high-risk westernized country among immigrants and Israel-born residents with relatively similar genetic predisposition to IBD[13,14], originating from countries with varying degrees of IBD risk.

Israel is a melting pot of various ethnicities and cultures, characterized by waves of immigration from all over the world. As a country with a population of 9.2 million (as of June 2020), Israel has absorbed 1.5 million Jewish immigrants since 1990 with little population drift[15]. Israel has a universal healthcare system where all residents are insured by one of four Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), making administrative studies relatively accurate. However, previous Israeli studies comparing IBD rates among Israel-born residents vs immigrants were conducted in small regional cohorts[16-23].

We aimed to compare the rate of IBD in first-generation immigrants vs Israel-born residents using a nationwide cohort of patients with IBD. We also aimed to determine whether the duration of residence in Israel affects the rate of IBD in these immigrants. Finally, we aimed to examine whether the rate of IBD in immigrants is related to the IBD risk in their country of origin.

We utilized the Israeli IBD Research Nucleus (epi-IIRN), a validated nationwide IBD cohort including 98% of the patients with IBD in Israel [50503 patients with IBD as of June 2020: 27490 with Crohn’s disease (CD) and 23013 with UC]. Case-ascertainment algorithms were validated for each of the four HMOs in Israel [89% sensitivity, 99% specificity, 92% positive predictive value (PPV), 99% negative predictive value (NPV)]. Further algorithms classified disease type as CD or UC (92% sensitivity, 97% specificity, 97% PPV, 92% NPV)[10,24].

We constructed a prevalence cohort including all Jewish patients with IBD in the epi-IIRN database who had an active diagnosis by June 2020, stratified by Israel-born and first-generation immigrants. Our focus on the Jewish population was based on the Israeli Law of Return, which almost exclusively gives Jews the right to receive citizenship in Israel. Indeed, 99.4% of immigrants in the epi-IIRN cohort immigrated under this definition.

Country of birth and date of immigration were retrieved from the HMOs’ electronic medical records for all patients with IBD. We categorized the countries of origin by degree of risk for IBD based on published systematic reviews[3,25] and according to Agrawal et al[5] as: Low risk [i.e., incidence of CD, < 1.95/100000 person-years (PY) and UC, < 3.10/100,000 PY], intermediate risk (i.e., CD, 1.95-6.38/100000 PY or UC, 3.10-7.71/100000 PY), and high risk (i.e., CD, > 6.38/100000 PY or UC, > 7.71/100000 PY). Each risk category was further stratified into age groups: 0-34, 35-65, and 65+ years as of June 2020. Duration of residence in Israel was inferred by immigration time periods, divided as the years < 1990, 1990-2001, and 2002-2020, based on immigration reports from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics[12]. When further stratifying by risk in country of origin and age groups, time periods were divided as the years < 1990 and 1990 onwards (i.e., at least 30 years of residence in Israel, or less than 30 years), again based on the national data published by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, with these time periods available for each risk stratum[15].

In order to minimize the possibility that IBD was diagnosed prior to immigration and was only new to the Israeli medical system, we performed a sensitivity analysis, which only included immigrants with at least a five-year lookback period from the date of immigration to the date of the first IBD code, as previously validated in the epi-IIRN cohort[24].

Patients who originated from countries with no risk data available or with missing data such as date of birth, country of origin, or immigration date were excluded. The date of death was obtained by linking each patient’s unique identifying code by deterministic approach to the Israeli Ministry of Health national mortality database. Socioeconomic status scores were based on a scale of 1-10 and grouped into three categories: 1-3, low; 4-6, intermediate; and 7-10, high[26], and current residence in Israel was divided into rural and urban based on address categorization by the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics.

Factors were compared between the cohorts using ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests, corrected for multiple comparisons by the Bonferroni method, as well as chi-square tests where appropriate. Point prevalence rates were calculated by dividing the annual number of living patients by the average population as of 2020, reported per 100000 with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and age-standardized by the direct method to the Israeli population for comparison between the groups. Proportions were compared via chi-squared contingency tables. SPSS version 28 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States) and R for statistical computing[27] were used for statistical analyses. The Institutional Review Board of Shaare Zedek Medical Center approved the study.

A total of 33544 Jewish patients were included in the study, of whom 18524 (55%) had CD and 15020 (45%) had UC; 85% were Israel-born (n = 28394) and 15% (n = 5150) were immigrants. Of the latter, 25 % (n = 1293) originated from high-risk countries, 70% (n = 3615) from intermediate-risk countries, and 5% (n = 242) from low-risk countries. Due to the small sample size in the low-risk group, immigrants from low- and intermediate-risk countries were grouped together and compared with those from high-risk countries. Data regarding the number of immigrants and the risk category assigned to each country are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Immigrants from Poland (n = 191) and Switzerland (n = 12) were excluded from this analysis, because the last available IBD data were from 1951-1960 and 1960-1969, respectively. The majority of immigrants were from former USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) countries (56%) and Europe (21%), followed by North America (11%), the Middle East (6%), South America (4.4%), Africa (1.5%), and Asia (0.1%). Additional socio-demographic characteristics are provided in Table 1.

| Origin from high-risk countries (n = 1293) | Origin from intermediate- and low-risk countries (n = 3857) | Israel-born (n = 28394) | |

| Prevalence-crude rate2 | 561.4 | 514.3 | 528.9 |

| Sex (Female) | 651 (50) | 1953 (51) | 14234 (50) |

| Age at immigration | 25 ± 18 | 25 ± 17 | N/A |

| IBD phenotype (Crohn’s disease) | 685 (53) | 1748 (45) | 16091 (57) |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 41 ± 18 | 46 ± 17 | 32 ± 15 |

| Age at June 2020 | 43 ± 17 | 60 ± 17 | 54 ± 19 |

| Immigration periods | |||

| < 1990 | 501 (39) | 1358 (35) | N/A |

| 1990-2001 | 229 (19) | 2199 (57) | |

| 2002-2020 | 543 (42) | 300 (8) | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Low | 65 (5) | 247 (7) | 1348 (5) |

| Intermediate | 550 (52.5) | 2247 (58) | 10680 (37) |

| High | 646 (50) | 1247 (32) | 15589 (55) |

| Missing | 32 (2.5) | 116 (3) | 777 (3) |

| Residential location | |||

| Rural | 111 (9) | 155 (4) | 3173 (11) |

| Urban | 1182 (91) | 3701 (96) | 25221 (89) |

Among the Israel-born cohort, 16091 (57%) had CD and 12303 (43%) had UC, while in the immigration cohort, UC dominated: 2433 (47%) CD vs 2717 UC (53%) (odds ratio (OR) = 1.46 (95%CI: 1.38-1.55); P < 0.001]. UC dominated among immigrants from low- and intermediate-risk countries [1748 (45%) CD vs 2109 (55%) UC, P < 0.001], while immigrants from high-risk countries were more likely to be diagnosed with CD [685 (53%) vs 608 (47%), P = 0.0023)].

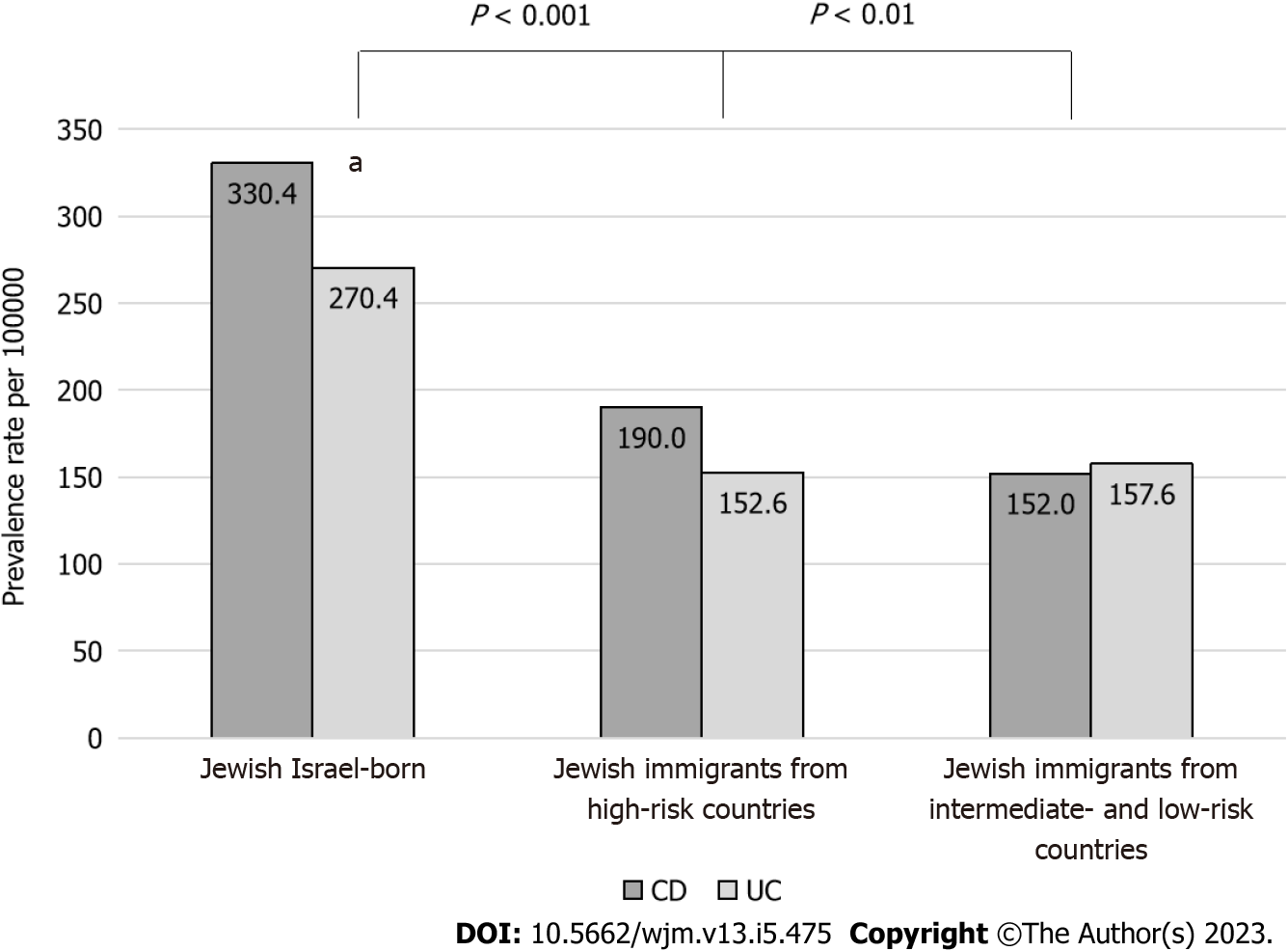

Crude IBD point prevalence rates in 2020 were highest among immigrants originating from high-risk countries [561.4 per 100000 (95%CI: 546.8-576.2)] followed by Israel-born residents [528.9 per 100000 (95%CI: 522.7-535.0)] and were lowest among immigrants from intermediate- and low-risk countries [514.3 per 100000 (95%CI: 493.2-535.9); P < 0.001]. In the immigration cohort, age-standardized point prevalence rates in 2020 were 342.6 per 100000 for immigrants originating from high-risk countries and 309.5 per 100000 for intermediate- and low-risk countries [OR = 1.1 (95%CI: 1.03-1.17); P = 0.0041]. For the Israel-born cohort, the standardized rate was twice as high (600.8 per 100000) as the entire immigration cohort (318.1 per 100000) [OR = 1.9 (1.65-2.17); P < 0.001]. When stratified by phenotype, CD prevalence rates were highest in the Israel-born cohort, followed by immigrants from high-risk countries, and were lowest among immigrants from intermediate- and low-risk countries (330.4 vs 190.0 vs 152.0 per 100000, respectively; P < 0.001; Figure 1).

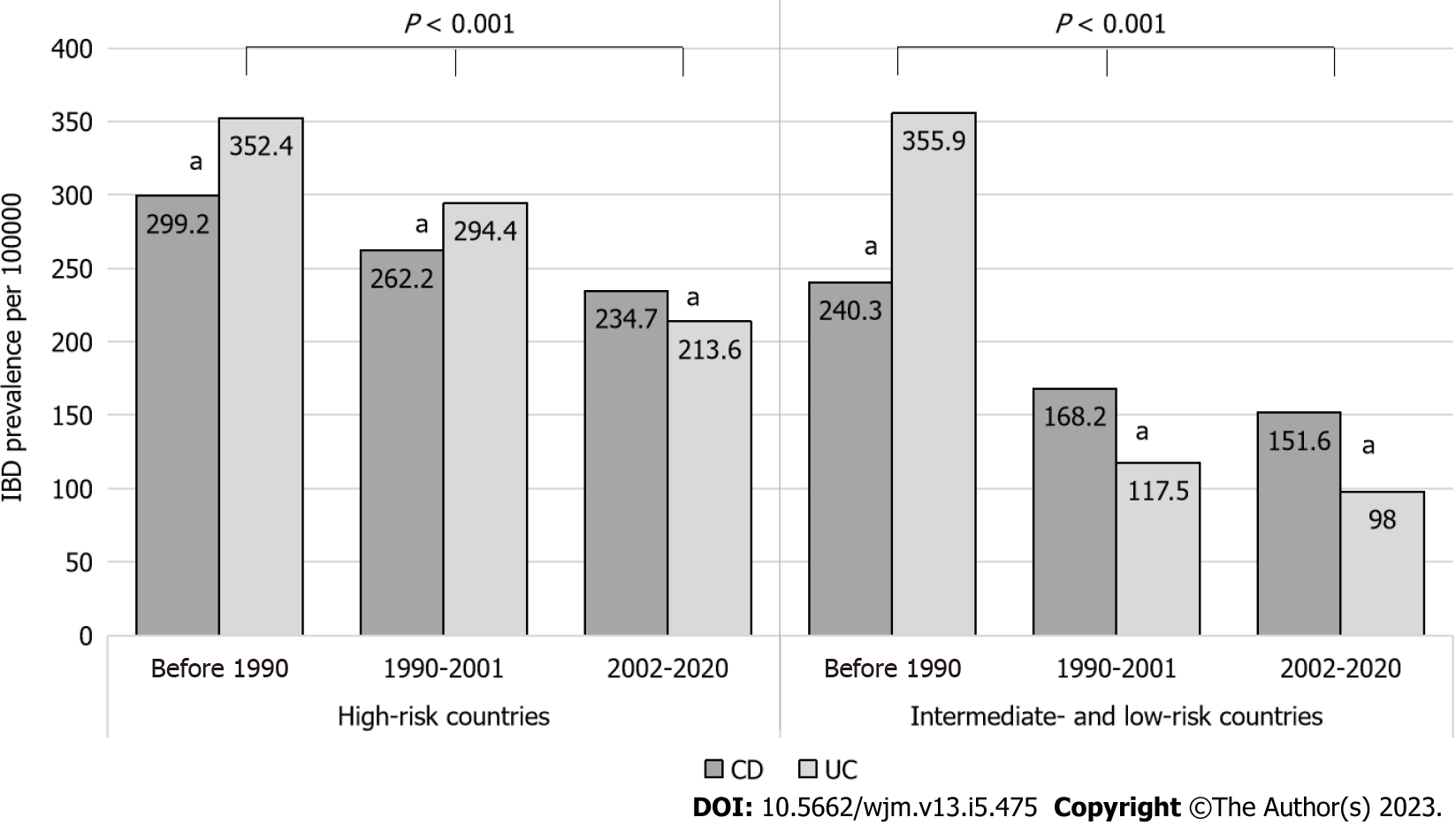

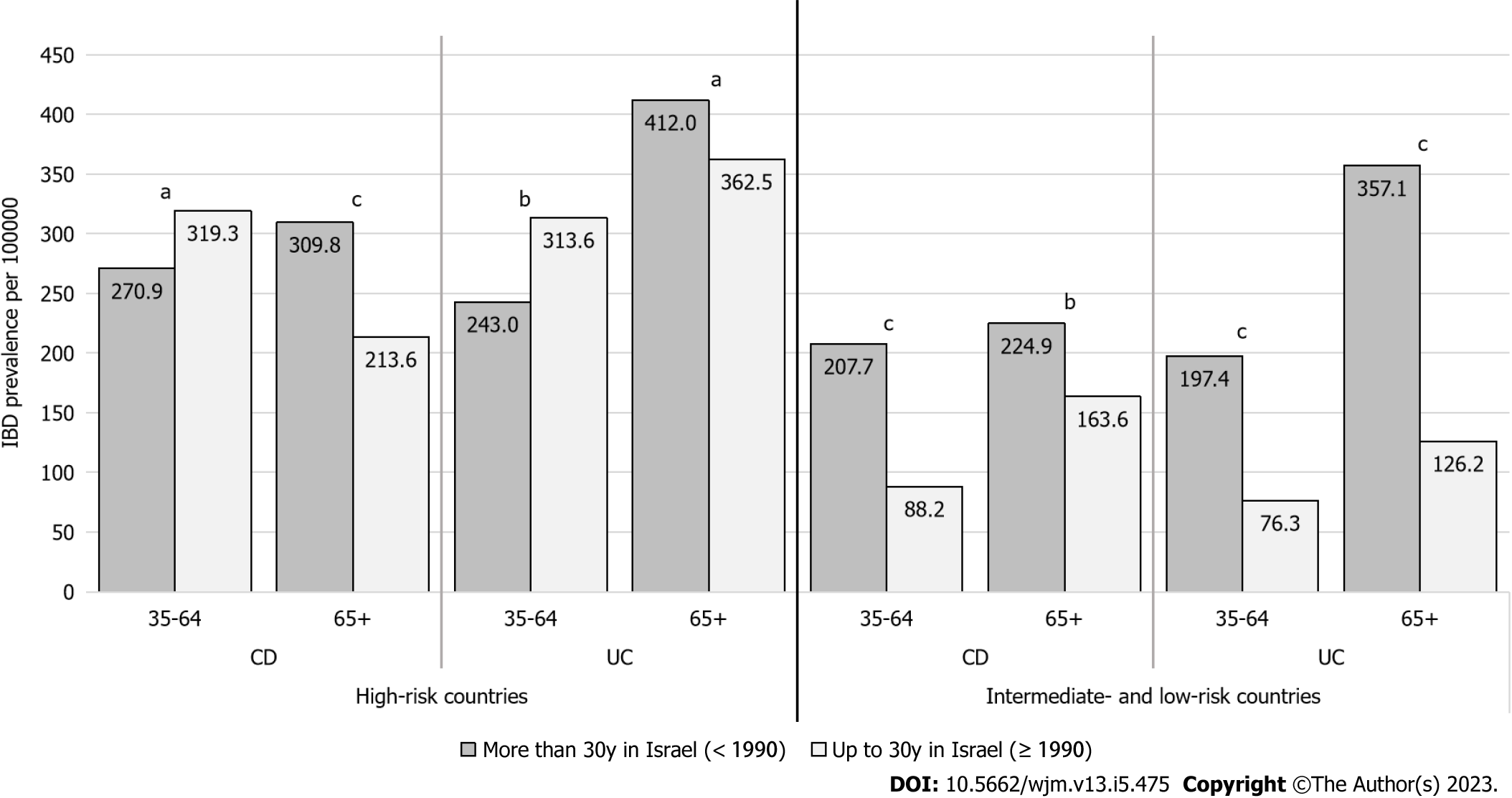

Among the immigrants, there was a significant association between longer duration of living in Israel and higher IBD prevalence rates, regardless of risk in the country of origin (Figure 2). CD became dominant among patients who immigrated after 1990 from intermediate- and low-risk countries, and from 2002 among patients who immigrated from high-risk countries. When stratifying by both IBD risk and age groups, prevalence for both CD and UC increased between time periods in each sub-group, with the exception of the group aged 35-64 years among immigrants from high-risk countries (Figure 3).

In the sensitivity analysis, there was a significant and positive association between longer duration in Israel and higher IBD prevalence rates for all countries of origin and among all age groups, including those aged 35-64 years (Supplementary Figure 1). For this analysis, 1057/5150 (21%) were excluded due to insufficient look-back period from the time of immigration; 1930 (47%) had CD and 2163 (53%) had UC; and 1115 (27%) originated from high-risk countries and 2978 (73%) from intermediate- and low-risk countries. UC was more common among individuals originating from intermediate- and low-risk countries [1571 (53%) UC vs 1407 (47%) CD, P < 0.001], as well as from high-risk countries [572 (51%) UC vs 543 (49%) CD], although in the latter, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.34).

In this nationwide study, we focused on the Jewish population to narrow the genetic variation of IBD that is usually present in immigration cohorts. We found that the IBD prevalence rate was lower among patients originating from intermediate- and low-risk regions compared to patients from high-risk regions but in both, the prevalence increased in association with duration of living in Israel after immigration. This finding, especially among immigrants from intermediate- and low-risk countries, lends support toward the role of environmental factors in IBD pathogenesis in Israel. In accordance with our findings, nationwide studies in Canada[8,28] and Sweden[9] have reported a lower risk of IBD among immigrants from low-risk countries compared to the non-immigrant population.

Previous studies on immigration to Israel were small and regional such as from the Beer Sheva region (1961-1985 and 1979-1987)[16,17], Central Israel (1970-1980)[18,19], the Kinneret sub-district of Northern Israel (1965-1989)[20,21], and Israeli Kibbutz settlements (1987-2007)[22,23]. These studies mainly compared IBD prevalence and incidence between Israel-born vs European-American-born and Asian-African-born Jewish immigrants. Most of these studies showed higher prevalence rates in European-American-born immigrants or Israel-born individuals, similar to our study. Our analysis, however, included all immigrants in Israel, including a substantial number of patients from low- and intermediate-risk countries, such as former USSR countries, who initially demonstrated higher UC rates but shifted to the local higher rate of CD in association with longer duration in Israel.

Although UC was predominant among patients who immigrated before 1990, CD became more prominent during the period from 2002 onwards, around the time when the switch from UC to CD dominance occurred in Israel (in 2006, as demonstrated in our previous study)[10]. High UC rates have been previously demonstrated in immigrants from both low-risk[29,30] and high-risk countries[7]. UC dominance, at least at first, may be explained by the hypothesis that UC is predominantly driven by exposure to environmental risk factors that may occur at any point in life, whereas CD is predominantly driven by genetic-environmental interactions in early life at critical stages of immunologic development[31].

Environmental risk factors affecting immigrant populations worldwide may include changes in diet, water supply, hygiene, socioeconomic status, access to the health care system, use of antibiotics, urbanization, and possibly psychological stress[32-34]. Vangay et al[35] demonstrated ‘westernization’ of the gut microbiome among 281 Southeast Asian individuals who immigrated to the United States. That study demonstrated loss of native gut microbiome diversity and function, amplified by longer duration in the United States.

Our study had several strengths. This study was the first to describe and compare the immigrant vs Israel-born IBD population in Israel on a national scale, who likely have similar genetic backgrounds, highlighting the role of environmental factors in IBD development in Israel. We utilized the national epi-IIRN cohort, which is based on validated algorithms accurately distinguishing patients with IBD, IBD type, and incident cases[24], thus minimizing selection bias and loss to follow-up. In Israel, healthcare coverage is universal, minimizing healthcare access bias between the immigrant and Israel-born groups. We conducted a sensitivity analysis that excluded patients without sufficient look-back period (and who may have had the disease at immigration), in an effort to minimize lead-time bias.

Limitations of our study include lack of access to national data necessary to calculate person-time and incidence rate ratios, as well as lack of data regarding lifestyle habits such as smoking and dietary intake among the immigration cohorts in the origin countries, as well as in Israel. Thus, we could not quantify the impact of specific environmental risk factors. We also excluded immigrants from countries without known IBD risk data, although the IBD immigration from these cohorts was negligible, such as some of the African countries (Supplementary Table 1).

It is almost impossible to fully disentangle periods of immigration and cohort effects explored in immigration studies in a meaningful way[36,37]. In our study, it is possible that there are periods of arrival cohort effects, but these cannot be distinguished from duration of residence effects. However, we did stratify the analysis by IBD risk in the country of origin, which may account for the cohort effect to a certain extent.

In conclusion, we found a high prevalence rate of IBD among immigrants to Israel and identified a positive association between duration of time after immigration and IBD prevalence, alluding to environmental risk factors in Israel. Future studies should explore associations between immigration with time to IBD onset, and should examine specific environmental factors among immigrants to further our understanding of the elusive IBD etiology.

Israel has a high rate of Jewish immigration and a high prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The study of IBD among immigrants is of paramount importance for several compelling reasons. Immigration itself facilitates population growth and changes in demographics, thereby influencing prevalence trends. Moreover, immigration introduces individuals to new environments, dietary habits, hygiene practices, and lifestyle behaviors, which can significantly alter their risk of developing IBD as they assimilate into their host countries.

Investigating IBD among immigrants provides a unique opportunity to dissect the complex interplay between genetics, environment, and migration in disease development, especially if focusing on a specific ethnic group of immigrants with similar predisposition to IBD. In this study, we compared IBD rates between first-generation immigrants originating from countries of varying IBD risk vs Israel-born residents, focusing specifically on the Jewish population in an effort to narrow the genetic variation of IBD that is usually present in immigration cohorts, in an increasingly interconnected world.

We aimed to compare the rate of IBD in first-generation immigrants vs Israel-born residents using a nationwide cohort of patients with IBD. We also aimed to determine whether the duration of residence in Israel affects the rate of IBD in these immigrants. Finally, we aimed to examine whether the rate of IBD in immigrants is related to the IBD risk in their country of origin.

Patients with a diagnosis of IBD as of June 2020 were included from the validated Israeli IBD Research Nucleus cohort that includes 98% of the Israeli population. We stratified the immigration cohort by IBD risk according to country of origin, time period of immigration, and age group as of June 2020.

Of the 33544 Jewish patients that were ascertained, 18524 (55%) had Crohn’s disease and 15020 (45%) had ulcerative colitis (UC); 28394 (85%) were Israel-born and 5150 (15%) were immigrants. UC was more prevalent in immigrants (2717; 53%) than non-immigrants (12303, 43%, P < 0.001), especially in the < 1990 immigration period. The prevalence was higher in patients immigrating from countries with high risk for IBD (561.4/100000) than those originating from intermediate-/low-risk countries (514.3/100000; P < 0.001); non-immigrant prevalence was 528.9/100000. After adjusting for age, longer duration in Israel was associated with a higher point prevalence rate in June 2020 (high-risk origin: Immigration < 1990: 645.9/100000, ≥ 1990: 613.2/100000, P = 0.043; intermediate/low-risk origin: < 1990: 540.5/100000, ≥ 1990: 192.0/100000, P < 0.001).

Our focus on the Jewish population was aimed at narrowing the genetic variation of IBD that is usually present in immigration cohorts. We found that the prevalence rate was lower among patients from intermediate-and low-risk regions compared to patients from high-risk regions but in both, the prevalence increased in association with duration in Israel after immigration. This finding, especially among immigrants from intermediate- and low-risk countries, lends support toward the role of environmental factors in IBD pathogenesis in Israel.

Future studies should explore associations between immigration with time to IBD onset, and should examine specific environmental factors among immigrants to further our understanding of the elusive IBD etiology.

The authors would like to thank Chagit Friss, Adi Mendelovich, and Rona Lujan from the Juliet Keidan Institute of Pediatric Gastroenterology at Shaare Zedek Medical Center for their expertise and assistance throughout the study; as well as Nir Zigman from Maccabi, Nirit Borovski from Leumit, Tzahi Levi from Meuhedet, and Liya Bieber from Clalit for their support in data extraction from the four HMOs’ databases. Eric Benchimol holds the Northbridge Financial Corporation Chair in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, a joint Hospital-University Chair between the University of Toronto, The Hospital for Sick Children, and the SickKids Foundation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Public, environmental and occupational health

Country/Territory of origin: Israel

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Moriya K, Japan; Perse M, Slovenia; Teng X, China; Wen XL, China; Hariyanto TI, Indonesia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 767] [Article Influence: 191.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:380-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 82.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769-2778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2677] [Cited by in RCA: 4109] [Article Influence: 513.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (110)] |

| 4. | Damas OM, Avalos DJ, Palacio AM, Gomez L, Quintero MA, Deshpande AR, Sussman DA, McCauley JL, Lopez J, Schwartz SJ, Abreu MT. Inflammatory bowel disease is presenting sooner after immigration in more recent US immigrants from Cuba. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Agrawal M, Corn G, Shrestha S, Nielsen NM, Frisch M, Colombel JF, Jess T. Inflammatory bowel diseases among first-generation and second-generation immigrants in Denmark: a population-based cohort study. Gut. 2021;70:1037-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Misra R, Faiz O, Munkholm P, Burisch J, Arebi N. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in racial and ethnic migrant groups. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:424-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Hammer T, Lophaven SN, Nielsen KR, von Euler-Chelpin M, Weihe P, Munkholm P, Burisch J, Lynge E. Inflammatory bowel diseases in Faroese-born Danish residents and their offspring: further evidence of the dominant role of environmental factors in IBD development. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1107-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Benchimol EI, Mack DR, Guttmann A, Nguyen GC, To T, Mojaverian N, Quach P, Manuel DG. Inflammatory bowel disease in immigrants to Canada and their children: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:553-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li X, Sundquist J, Hemminki K, Sundquist K. Risk of inflammatory bowel disease in first- and second-generation immigrants in Sweden: a nationwide follow-up study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1784-1791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stulman MY, Asayag N, Focht G, Brufman I, Cahan A, Ledderman N, Matz E, Chowers Y, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S, Odes S, Dotan I, Balicer RD, Benchimol EI, Turner D. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Israel: A Nationwide Epi-Israeli IBD Research Nucleus Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1784-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Atia O, Magen Rimon R, Ledderman N, Greenfeld S, Kariv R, Loewenberg Weisband Y, Shaoul R, Matz E, Odes S, Goren I, Yanai H, Dotan I, Turner D. Prevalence and Outcomes of No Treatment Versus 5-ASA in Ulcerative Colitis: A Nationwide Analysis From the epi-IIRN. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dashefsky A, Deamicis J, Lazerwitz B. American emigration: similarities and differences among migrants to Australia and Israel. Comp Soc Res. 1984;7:337-347. [PubMed] |

| 13. | The history of genetics in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:294. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ostrer H, Skorecki K. The population genetics of the Jewish people. Hum Genet. 2013;132:119-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, Population - Statistical Abstract of Israel 2021. Available from: https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/publications/Pages/2021/Population-Statistical-Abstract-of-Israel-2021-No.72.aspx. |

| 16. | Odes HS, Fraser D, Krawiec J. Ulcerative colitis in the Jewish population of southern Israel 1961-1985: epidemiological and clinical study. Gut. 1987;28:1630-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Odes HS, Fraser D, Krawiec J. Inflammatory bowel disease in migrant and native Jewish populations of southern Israel. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:36-8; discussion 50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Grossman A, Fireman Z, Lilos P, Novis B, Rozen P, Gilat T. Epidemiology of ulcerative colitis in the Jewish population of central Israel 1970-1980. Hepatogastroenterology. 1989;36:193-197. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Fireman Z, Grossman A, Lilos P, Hacohen D, Bar Meir S, Rozen P, Gilat T. Intestinal cancer in patients with Crohn's disease. A population study in central Israel. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:346-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shapira M, Tamir A. Crohn's disease in the Kinneret sub-district, Israel, 1960-1990. Incidence and prevalence in different ethnic subgroups. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:231-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shapira M, Tamir A. Ulcerative colitis in the Kinneret sub district, Israel 1965-1994: incidence and prevalence in different subgroups. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:134-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Birkenfeld S, Zvidi I, Hazazi R, Niv Y. The prevalence of ulcerative colitis in Israel: a twenty-year survey. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:743-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zvidi I, Hazazi R, Birkenfeld S, Niv Y. The prevalence of Crohn's disease in Israel: a 20-year survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:848-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Friedman MY, Leventer-Roberts M, Rosenblum J, Zigman N, Goren I, Mourad V, Lederman N, Cohen N, Matz E, Dushnitzky DZ, Borovsky N, Hoshen MB, Focht G, Avitzour M, Shachar Y, Chowers Y, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S, Odes S, Schwartz D, Dotan I, Israeli E, Levi Z, Benchimol EI, Balicer RD, Turner D. Development and validation of novel algorithms to identify patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in Israel: an epi-IIRN group study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:671-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | IOIBD GIVES (Global IBD Visualization of Epidemiology Studies). 2020; Available from: https://arcg.is/0nfan9. |

| 26. | Ghersin I, Khteeb N, Katz LH, Daher S, Shamir R, Assa A. Trends in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease among Jewish Israeli adolescents: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:556-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, To T, Mack DR, Nguyen GC, Gommerman JL, Croitoru K, Mojaverian N, Wang X, Quach P, Guttmann A. Asthma, type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and inflammatory bowel disease amongst South Asian immigrants to Canada and their children: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jayanthi V, Probert CSJ, Pinder D, Wicks ACB, Mayberry JF. Epidemiology of Crohn's disease in Indian migrants and the indigenous population in Leicestershire. QJM. 1992;82:125-138. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Pinder D, Wicks AC, Mayberry JF. Epidemiological study of ulcerative proctocolitis in Indian migrants and the indigenous population of Leicestershire. Gut. 1992;33:687-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Agrawal M, Burisch J, Colombel JF, C Shah S. Viewpoint: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Among Immigrants From Low- to High-Incidence Countries: Opportunities and Considerations. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:563-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 804] [Cited by in RCA: 693] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Amre DK, D'Souza S, Morgan K, Seidman G, Lambrette P, Grimard G, Israel D, Mack D, Ghadirian P, Deslandres C, Chotard V, Budai B, Law L, Levy E, Seidman EG. Imbalances in dietary consumption of fatty acids, vegetables, and fruits are associated with risk for Crohn's disease in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2016-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Wilson J, Williams J, Hair C, Knight R, Prewett E, Dabkowski P, Alexander S, Allen B, Dowling D, Connell W, Desmond P, Bell S. Influence of food and lifestyle on the risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease. Intern Med J. 2016;46:669-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Vangay P, Johnson AJ, Ward TL, Al-Ghalith GA, Shields-Cutler RR, Hillmann BM, Lucas SK, Beura LK, Thompson EA, Till LM, Batres R, Paw B, Pergament SL, Saenyakul P, Xiong M, Kim AD, Kim G, Masopust D, Martens EC, Angkurawaranon C, McGready R, Kashyap PC, Culhane-Pera KA, Knights D. US Immigration Westernizes the Human Gut Microbiome. Cell. 2018;175:962-972.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 521] [Cited by in RCA: 509] [Article Influence: 72.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bell A, Jones K. The impossibility of separating age, period and cohort effects. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:163-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fosse E, Winship C. Analyzing age-period-cohort data: A review and critique. Annu Rev Sociol. 2019;45:467-492. [DOI] [Full Text] |