Published online Mar 6, 2016. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v5.i2.158

Peer-review started: June 15, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Revised: November 11, 2015

Accepted: January 27, 2016

Article in press: January 29, 2016

Published online: March 6, 2016

Processing time: 263 Days and 9 Hours

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) is relatively rare compared to urothelial carcinoma of the lower tract, comprising only 5%-10% of all urothelial cancers. Although both entities share histologic properties, UTUC tends to be more invasive at diagnosis and portend a worse prognosis, with a 5 year overall mortality of 23%. To date, the gold standard management of UTUC has been radical nephroureterectomy (RNU), with nephron sparing techniques reserved for solitary kidneys or cases where the patient could not tolerate radical surgery. Limited data from these series, as well as select series where nephron-sparing endoscopic management has been offered to a broader patient base, suggest that minimally invasive, nephron sparing techniques can offer comparable oncologic and survival outcomes to RNU in appropriately selected patients. We review the current literature on the topic and discuss long term outcomes and sequelae of the gold standard treatment, RNU. We also discuss the oncologic outcomes of minimally invasive, endoscopic management of UTUC. Our goal is to provide the reader a comprehensive overview of the current state of the field in order to inform and guide their treatment decisions.

Core tip: In the appropriate patient population, minimally invasive endoscopic treatment of upper tract urothelial carcinoma provides comparable oncologic and survival outcomes to the gold standard radical nephroureterectomy.

- Citation: Fiuk JV, Schwartz BF. Upper tract urothelial carcinoma: Paradigm shift towards nephron sparing management. World J Nephrol 2016; 5(2): 158-165

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v5/i2/158.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v5.i2.158

Urothelial cell carcinoma (UCC), a common malignancy encountered by urologists, is the 4th most common overall neoplasm and the 8th most common cause of cancer death in men. Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC), however, is a relatively rare neoplasm, comprising only 5%-10% of all UCCs and 5%-7% of all renal neoplasms[1-3]. Despite their histologic similarities, UTUC and lower tract UCC may represent two distinct oncologic entities. The natural history of both disease states differs, in that 60% of UTUCs are invasive at diagnosis compared to 15%-25% of lower tract UCCs. UTUC portends a worse prognosis, with an overall 28% 5-year extra vesicle recurrence rate and a 23% 5-year mortality[4]. The prognosis for muscle invasive UTUC is particularly grim, with a 5 year cancer specific survival (CSS) less than 50% for pT2 /T3 lesions and less than 10% for pT4 lesions[5,6].

Given the wide body of lower tract UCC literature and the well documented bladder tumor recurrence rate following UTUC, management and surveillance of lower tract disease is standardized and well adhered to. In contrast, most of the recommendations for management of UTUC and subsequent surveillance have been extrapolated from current guidelines for lower tract UCC. Only one specific guideline from the European Association of Urology (EUA) currently exists for the surgical management of UTUC, as well as no randomized controlled trials (RCT) compared to 238 RCTs for bladder cancer[7,8]. UTUC is, at best, included as a subset in guidelines for bladder cancer amongst other professional societies such as the American Urological Association (AUA) and International Consultation on Urological Diseases (IDUC)[9-11].

The gold standard treatment for UTUC is radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) with ipsilateral bladder cuff excision[4]. As our instrumentation technology improves, endoscopic management of UTUC has become feasible. Early experience with endoscopic management of UTUC has been limited to patients with solitary kidneys, bilateral disease, or those who are not surgical candidates to undergo RNU. Data from these cases, though limited to retrospective, unmatched comparative studies, demonstrates no short and mid-term difference in overall survival and CSS between endoscopic management and RNU[12].

The lack of concrete management guidelines for UTUC, as well as the feasibility of nephron sparing treatment techniques, raises questions of the appropriateness of our current management strategies. In this article we review existing treatment options for UTUC, their effectiveness from an oncologic standpoint, as well as the morbidity incurred long term due to impaired renal function. Though we encourage the reader to come to their own conclusion, we propose that in appropriately selected patients, endoscopic treatment of UTUC is as effective as RNU with lower long term renal complications.

We performed a review of the literature from January 1980 to January 2015, including all English language articles using the search terms “endoscopic management”, “ureteroscopic management”, “percutaneous management” and “UTUC”. A total of 236 articles were reviewed, yielding 66 articles pertinent to the topic. Outcome measures of upper tract recurrence, overall survival, and CSS were extracted from retrospective and prospective studies.

As previously discussed, UTUC represents a relatively rare subset of urothelial carcinoma. Bladder tumors represent 90%-95% of all UCs, while UTUCs account for only 5%-10% of all UCs, with an annual incidence in western countries of 2 new cases per 100000 people[3]. Among UTUCs, pyelocaliceal tumors are twice as common as ureteral tumors. Concurrent bladder tumors are diagnosed with UTUC in 17% of UCC patients. Bladder recurrence after UTUC is common, occurring in 22%-47% of patients, while contralateral upper tract recurrence occurs in only 2%-6%[13]. Upper tract recurrence after a primary bladder tumor is reported as rare, with an incidence of 1.7%-3.1%[14,15]. UTUCs have a peak incidence in the elderly population, between age 70 and 80, and are three times more prevalent in men than in women[16]. Hereditary UTUC exists as a component of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome[17].

The most common presenting symptom of UTUC, occurring in 70%-80% of cases, is either gross or microscopic hematuria[18]. Flank pain is less common, occurring in 20%-40% of cases, while presentation with a lumbar mass is even more rare, occurring 10%-20% of the time. Both of these entities likely represent advanced disease with worsened prognosis[19,20].

CT imaging with and without IV contrast has replaced IV excretory urography and ultrasound as the gold standard imaging modality with the highest accuracy for diagnosing UTUC. Its sensitivity ranges from 67%-100% and specificity from 93%-99%, depending on the technique used[18]. CT imaging cannot accurately stage UTUC, as staging relies on depth of invasion, which is difficult to determine on imaging alone. However, the presence of hydronephrosis in conjunction with known or suspected UTUC portends a worse prognosis, as it is associated with advanced stage disease[21,22]. Other imaging modalities, such as contrast enhanced MRI, are still in their infancy for diagnosis of UTUC, with a limited sensitivity of 75% for tumors < 2 cm[23].

Cytology alone is of limited utility as it is less sensitive for UTUC than for bladder tumors. If utilized, it should be performed in situ, with samples being taken directly from the collecting system or ureter via the ureteroscope[24]. Flexible ureteroscopy is a highly effective means of diagnosis, either through direct visualization of tumor in the ureter, renal pelvis and collecting system, or via ureteroscopic biopsies, which approach 90% accuracy regardless of the total volume of tissue sample obtained[25]. As with CT imaging, accurate staging is difficult with ureteroscopy and biopsies, as the nature of the biopsy forceps makes obtaining muscle in the specimen difficult. Tumor grade is often used as a proxy for stage given that most high grade tumors are also high stage[5]. Though there are some who advocate for use of imaging findings alone for diagnosis of UTUC, this makes determining the prognosis difficult, as one is not able to determine tumor grade (and thus, by proxy, estimate stage) without tissue specimens. Our recommendation is thus to perform ureteroscopic biopsies on all patients with suspected UTUC.

The gold standard treatment for UTUC is RNU with concomitant management of the ipsilateral intramural ureter[4]. Traditionally this was performed as an open procedure, adherent to standard oncologic principles, namely avoiding entry into the urinary tract to prevent gross spillage of tumor. With the evolution of laparoscopic and robotic surgery, minimally invasive variants of RNU have been developed. Thus far, short to mid term oncologic outcomes seem to be equivalent between laparoscopic and open techniques; however, we currently lack the follow up to prove long term oncologic equivalence between these modalities[26]. Management of the ipsilateral intramural ureter is critical for adequate recurrence free survival (RFS), as this is the area of highest recurrence. Various methods exist for excising the intramural ureter - extravesical, transvesical, and endoscopic (the “pluck” technique). All three have shown no difference in CSS and OS; endoscopic management techniques have, however, shown higher local bladder recurrence rates[27]. It is not currently standard practice to perform a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (LND) along with RNU; a growing body of data suggest it increases median time until recurrence and improves CSS[28].

Aside from the immediate perioperative complications of RNU, which do not differ greatly from any large oncologic resection, patients undergoing this procedure must contend with the long term impact of losing an entire renal unit. Initial studies on creatinine clearance and GFR, performed on the donor nephrectomy population, did not show a long term decrease in renal function[29-31]. However, one could argue that these donor nephrectomy patients represent a carefully selected cohort of patients that lack the risk factors for renal deterioration after major surgery. A study of patients undergoing nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma, arguably a patient cohort more closely matched to that of the UTUC population, showed that 10% of patients had significant deterioration of their creatinine post nephrectomy[32]. A study of 131 patients undergoing nephroureterectomy showed an 18% decrease in GFR at a median of 5 year follow up[33]. Another retrospective study of 374 patients undergoing RNU showed an even higher decrease in GFR, at 32%, with no significant trend towards GFR recovery over time[34]. It would seem apparent from the data that nephroureterectomy does indeed lead to significant impairment of renal function.

Renal impairment, end stage renal disease (ESRD) in particular, accounts for a large percentage of health care spending in the elderly[35]. Cost analysis data from UTUC patients undergoing either RNU or renal sparing treatment for UTUC demonstrates a 3-fold to 10-fold cost savings of nephron sparing treatment over RNU over a 10 year period with similar oncologic outcomes[36]. Perhaps more importantly, overall survival and quality of life of patients whose renal insufficiency necessitates dialysis has been proven to be greatly diminished compared to the non dialysis dependent population[37]. Urologists have globally accepted the aforementioned arguments as strong reasons for renal preservation in the management of small renal masses - could these principles be selectively applied to UTUC?

The rationale for conservative surgery for UTUC stems from the fact that most UTUC is superficial and low grade[38]. Thus, coupled with the aforementioned drawbacks of renal loss and decreased GFR, as well as improvements in endoscopic technology, allow for pursuit of renal sparing techniques. Currently available nephron-sparing treatments for UTUC include ureteroscopic retrograde tumor ablation, percutaneous antegrade tumor ablation, or segmental ureterectomy. As the focus of this review is endoscopic management of UTUC, segmental will not be discussed further here.

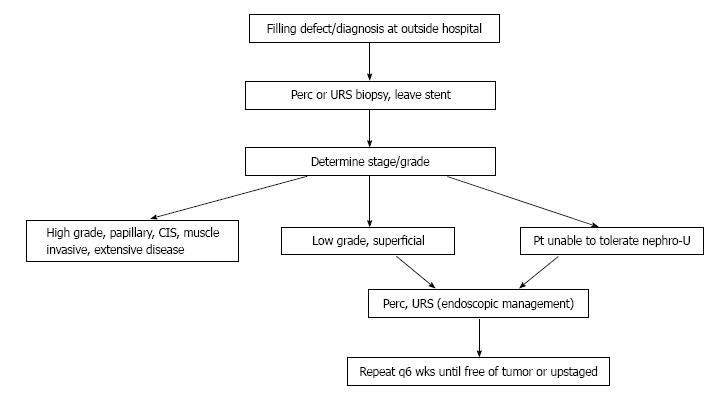

Patient selection is critical, as currently endoscopic management techniques are only advisable for low grade, small volume tumors or for patients who would otherwise not be fit to undergo RNU[7] (Figure 1). The decision between retrograde ureteroscopic tumor management and antegrade percutaneous ablation depends primarily on tumor size and location. Large tumors in the renal pelvis are best approached in a percutaneous fashion, while ureteral tumors lend themselves to a ureteroscopic approach. Small tumors in the collecting system may be approached by either fashion[12,38].

Currently no randomized controlled trials exist comparing endoscopic management techniques to the gold standard radical nephroureterectomy. Most of the published data come from small, retrospective and unmatched comparative studies. A 2014 meta-analysis of eight retrospective series, totaling 1002 patients, demonstrated no statistically significant difference in overall survival and CSS between the two modalities. The authors hesitated to conclude oncologic equivalence given the low level of the evidence[12] Additionally, patients tended to be selected for favorable tumor characteristics, such as low grade features and small tumor size. Analysis of all the existing literature reveals that ureteroscopic ablation of the tumor is associated with high rates of upper urinary tract recurrence (15%-90%) and intravesical recurrence (12%-70%). Tumor grade, size and multifocality predict upper tract recurrence while previous history of bladder cancer predicts intravesical recurrence (Table 1)[39-57]. The large variations in population size, initial tumor characteristics and length of follow up likely explain the broad range of observed outcomes.

| Ref. | n | Grade on biopsy (G1/G2/G3 vs LG/HG) | F/U (mo) | Outcomes (%) |

| Schmeller et al[39] (1989) | 16 | 6/10/0 | 14 | 19 UTR, 100 OS, 100 CSS |

| Andersen et al[40] (1989) | 10 | NA | 35 | NA |

| Gaboardi et al[41] (1994) | 18 | 12/6/0 | 15 | 50 UTR, 100 OS, 100 CSS |

| Engelmeyer et al[42] (1996) | 10 | 9/1/0 | 10 | 70 UTR, 90 OS, 100 CSS |

| Chen et al[57] (2000) | 23 | 22LG/21HG | 23 | 64 UTR, 12 IVR |

| Daneshmand et al[43] (2003) | 30 | 7/6/14 | 31 | 90 UTR, 23 IVR, 77 OS, 97 CSS |

| Matsuoka et al[44] (2003) | 27 | 10/2/0 | 33 | 26 UTR, 15 IVR |

| Iborra et al[45] (2003) | 23 | NA | NA | 35 UTR, 96 CSS |

| Johnson et al[46] (2005) | 35 | 35/0/0 | 32 | 68 UTR, 100 CSS |

| Rouprêt et al[47] (2006) | 27 | 19LG/8HG | 52 | 15 UTR, 22 IVR, 77 OS, 81 CSS |

| Reisinger et al[48] (2007) | 10 | 10/0/0 | 73 | 50 UTR, 70 IVR, 100 OS, 100 CSS |

| Krambeck et al[49] (2007) | 37 | 2/13/7 | 32 | 62 UTR, 37 IVR, 35 OS, 70 CSS |

| Painter et al[50] (2008) | 45 | NA | NA | 89 CSS |

| Lucas et al[51] (2008) | 39 | 27LG/12HG | 33 | 46 UTR, 62 OS, 82 CSS |

| Pak et al[36] (2009) | 57 | NA | 53 | 90 UTR, 93 OS, 95 CSS |

| Cornu et al[52] (2010) | 35 | 16LG/6HG | 24 | 60 UTR, 40 IVR, 100 OS, 100 CSS |

| Gadzinski et al[53] (2010) | 34 | NA | 58 | 84 UTR, 75 OS, 100 CSS |

| Cutress et al[54] (2012) | 73 | 34/19/6 | 54 | 69 UTR, 43 IVR, 60 OS, 90 CSS |

| Grasso et al[55] (2012) | 80 | 66LG/14HG | 38 | 81 UTR, 59 IVR, 74 OS, 87 CSS |

| Fajkovic et al[56] (2013) | 20 | 14LG/3HG | 20 | 25 UTR, 15 IVR, 45 OS, 95 CSS |

Similarly, the only data on outcomes of percutaneous management of UTUC come from retrospective series (Table 2)[58-66]. Overall, patients managed percutaneously had similar clinical features to those managed ureterscopically - namely low grade, small focal tumors. Those undergoing percutaneous ablation had lower rates of upper tract recurrence (10%-65%) and intravesical recurrence (10%-42%) than those treated with the ureteroscopic approach. Given the high rate of comorbidities, much like in the uretoscopic population, the overall survival was poor (68%-96%) while the CSS was high (75%-100%).

| Ref. | n | Grade on biopsy (G1/G2/G3 vs LG/HG) | F/U (mo) | Outcomes (%) |

| Tasca et al[58] (1992) | 10 | 1/5/0 | 19 | 50 UTR, 90 OS, 100 CSS |

| Fuglsig et al[59] (1995) | 26 | NA | 21 | 31 UTR, 96 OS, 100 CSS |

| Plancke et al[60] (1995) | 10 | 6/3/11 | 28 | 10 UTR, 10 IVR, 90 OS, 100 CSS |

| Patel et al[61] (1996) | 26 | 11/11/1 | 45 | 35 UTR, 42 IVR, 75 OS, 91 CSS |

| Clark et al[62] (1999) | 17 | 6/7/4 | 24 | 33 UTR, 75 OS, 82 CSS |

| Goel et al[63] (2003) | 20 | 15LG/5HG | 64 | 65 UTR, 15 IVR, 75 CSS |

| Palou et al[66] (2004) | 34 | 7/21/5 | 51 | 44 UTR, 74 OS, 94 CSS |

| Rouprêt et al[64] (2007) | 24 | 17LG/7HG | 62 | 13 UTR, 17 IVR, 79 OS, 83 CSS |

| Rastinehead et al[65] (2009) | 89 | 50LG/39HG | 61 | 33 UTR, 68 OS |

| Fiuk (current study) | 65 | 34LG/33HG | 28 | 55 OS, 87 CSS |

Currently, the only “imperative” indications for systematically offering nephron sparing treatment of UTUC include anatomically or functionally solitary kidneys, substantial renal insufficiency with the impending threat of hemodyalisis or bilateral UTUC[7]. We believe that, though limited in its retrospective nature, the exisiting data indicate that the patient population to whom nephron sparing treatment is routinely offered as a first line option should be expanded.

UTUC continues to challenge urologists as a potentially devastating disease that tends to affect older, sicker patients. As this review of the literature demonstrates, patients treated with ureteroscopic or percutaneous means have a much higher CSS than OS, meaning that they eventually succumb to their comorbidities, and not their cancer. Thus, we believe that patients with significant comorbidities make excellent candidates for first line nephron sparing options. Ureteroscopic and percutaneous approaches offer similar CSS, at least according to medium term data, while avoiding the morbidity and potential of a RNU for an already unhealthy patient population.

Amongst otherwise healthy UTUC patients, we believe nephron sparing treatments should still be offered to those patients with low grade, low stage disease. Although UTUC is more often invasive at diagnosis, truly low grad and low stage disease seems to follow a similarly indolent course, with frequent recurrence but rare progression, as low grade bladder cancer[2,3,7]. Thus, as endoscopic technology and techniques improve, allowing for better ureteroscopic evaluation and biopsy, we should be better able to separate low grade from high grade disease. Patients with low grade disease have shown excellent CSS in the existing endoscopic management literature; using these treatments would allow us to spare them the morbidity of losing a renal unit.

Post-treatment surveillance is critical for achieving excellent CSS outcomes. Thus, patients considered for endoscopic management of their UTUC must be compliant. At our institution we repeat ureteroscopic or percutaneous surveillance ever 3-6 mo for 2 years and then annually; similar variations on this surveillance protocol exist throughout the literature. Additionally, CT imaging allows for detection of progression to metastatic disease and should be performed at regular time intervals. Urinary cytology is not as useful in UTUC and thus is left to the surgeon’s discretion.

We thus propose that nephron sparing treatment of UTUC, either ureteroscopic or percutaneous, be offered as a first line therapy to the following patient populations: (1) any patient with an anatomically or functionally solitary kidney; (2) any patient with renal insufficiency great enough to impose the threat of hemodyalisis with any further renal insult; (3) any patient with multiple bilateral UTUC tumors; (4) any patient with comorbidities great enough to be life limiting or to incur additional risk with nephroureterectomy; and (5) any patient with low grade, low stage disease who can be trusted to commit to 3-6 mo surveillance.

By using a risk-adapted strategy for expanding current indications for first line endoscopic treatment of UTUC, we hope to minimize renal unit loss without compromising oncologic safety. Development of improved biopsy techniques, urothelial cancer biomarkers, and improved prediction nomograms may help further delineate these indications in the future.

P- Reviewer: Fernandez-Pello S, Soria F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8970] [Article Influence: 690.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ristau BT, Tomaszewski JJ, Ost MC. Upper tract urothelial carcinoma: current treatment and outcomes. Urology. 2012;79:749-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ploeg M, Aben KK, Kiemeney LA. The present and future burden of urinary bladder cancer in the world. World J Urol. 2009;27:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in RCA: 645] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Margulis V, Shariat SF, Matin SF, Kamat AM, Zigeuner R, Kikuchi E, Lotan Y, Weizer A, Raman JD, Wood CG. Outcomes of radical nephroureterectomy: a series from the Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Collaboration. Cancer. 2009;115:1224-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 731] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abouassaly R, Alibhai SM, Shah N, Timilshina N, Fleshner N, Finelli A. Troubling outcomes from population-level analysis of surgery for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urology. 2010;76:895-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jeldres C, Sun M, Isbarn H, Lughezzani G, Budäus L, Alasker A, Shariat SF, Lattouf JB, Widmer H, Pharand D, Arjane P, Graefen M, Montorsi F, Perrotte P, Karakiewicz PI. A population-based assessment of perioperative mortality after nephroureterectomy for upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. Urology. 2010;75:315-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Compérat E, Zigeuner R, Sylvester R, Burger M, Cowan N, Böhle A, Van Rhijn BW, Kaasinen E. European guidelines on upper tract urothelial carcinomas: 2013 update. Eur Urol. 2013;63:1059-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rai BP, Shelley M, Coles B, Biyani CS, El-Mokadem I, Nabi G. Surgical management for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD007349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rai BP; NCCN. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Bladder Cancer V.2.2012. USA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2012; . |

| 10. | Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, Pruthi RS, Seigne JD, Skinner EC, Wolf JS, Schellhammer PF. Guideline for the management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;178:2314-2330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 577] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Soloway MS. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: Recommendations on bladder cancer-progress in a cancer that lacks the limelight. Eur Urol. 2013;63:1-3. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Yakoubi R, Colin P, Seisen T, Léon P, Nison L, Bozzini G, Shariat SF, Rouprêt M. Radical nephroureterectomy versus endoscopic procedures for the treatment of localised upper tract urothelial carcinoma: a meta-analysis and a systematic review of current evidence from comparative studies. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1629-1634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cosentino M, Palou J, Gaya JM, Breda A, Rodriguez-Faba O, Villavicencio-Mavrich H. Upper urinary tract urothelial cell carcinoma: location as a predictive factor for concomitant bladder carcinoma. World J Urol. 2013;31:141-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oldbring J, Glifberg I, Mikulowski P, Hellsten S. Carcinoma of the renal pelvis and ureter following bladder carcinoma: frequency, risk factors and clinicopathological findings. J Urol. 1989;141:1311-1313. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Schwartz CB, Bekirov H, Melman A. Urothelial tumors of upper tract following treatment of primary bladder transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 1992;40:509-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shariat SF, Favaretto RL, Gupta A, Fritsche HM, Matsumoto K, Kassouf W, Walton TJ, Tritschler S, Baba S, Matsushita K. Gender differences in radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. World J Urol. 2011;29:481-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rouprêt M, Yates DR, Comperat E, Cussenot O. Upper urinary tract urothelial cell carcinomas and other urological malignancies involved in the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (lynch syndrome) tumor spectrum. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1226-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cowan NC. CT urography for hematuria. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Raman JD, Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Lotan Y, Sagalowsky AI, Roscigno M, Montorsi F, Bolenz C, Weizer AZ, Wheat JC. Does preoperative symptom classification impact prognosis in patients with clinically localized upper-tract urothelial carcinoma managed by radical nephroureterectomy? Urol Oncol. 2011;29:716-723. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ito Y, Kikuchi E, Tanaka N, Miyajima A, Mikami S, Jinzaki M, Oya M. Preoperative hydronephrosis grade independently predicts worse pathological outcomes in patients undergoing nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2011;185:1621-1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Van Der Molen AJ, Cowan NC, Mueller-Lisse UG, Nolte-Ernsting CC, Takahashi S, Cohan RH. CT urography: definition, indications and techniques. A guideline for clinical practice. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:4-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Messer JC, Terrell JD, Herman MP, Ng CK, Scherr DS, Scoll B, Boorjian SA, Uzzo RG, Wille M, Eggener SE. Multi-institutional validation of the ability of preoperative hydronephrosis to predict advanced pathologic tumor stage in upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:904-908. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Takahashi N, Glockner JF, Hartman RP, King BF, Leibovich BC, Stanley DW, Fitz-Gibbon PD, Kawashima A. Gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance urography for upper urinary tract malignancy. J Urol. 2010;183:1330-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Messer J, Shariat SF, Brien JC, Herman MP, Ng CK, Scherr DS, Scoll B, Uzzo RG, Wille M, Eggener SE. Urinary cytology has a poor performance for predicting invasive or high-grade upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. BJU Int. 2011;108:701-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rojas CP, Castle SM, Llanos CA, Santos Cortes JA, Bird V, Rodriguez S, Reis IM, Zhao W, Gomez-Fernandez C, Leveillee RJ. Low biopsy volume in ureteroscopy does not affect tumor biopsy grading in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1696-1700. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Ni S, Tao W, Chen Q, Liu L, Jiang H, Hu H, Han R, Wang C. Laparoscopic versus open nephroureterectomy for the treatment of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review and cumulative analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1142-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Xylinas E, Rink M, Cha EK, Clozel T, Lee RK, Fajkovic H, Comploj E, Novara G, Margulis V, Raman JD. Impact of distal ureter management on oncologic outcomes following radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2014;65:210-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Brausi MA, Gavioli M, De Luca G, Verrini G, Peracchia G, Simonini G, Viola M. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLD) in conjunction with nephroureterectomy in the treatment of infiltrative transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the upper urinary tract: impact on survival. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1414-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Anderson RG, Bueschen AJ, Lloyd LK, Dubovsky EV, Burns JR. Short-term and long-term changes in renal function after donor nephrectomy. J Urol. 1991;145:11-13. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Goldfarb DA, Matin SF, Braun WE, Schreiber MJ, Mastroianni B, Papajcik D, Rolin HA, Flechner S, Goormastic M, Novick AC. Renal outcome 25 years after donor nephrectomy. J Urol. 2001;166:2043-2047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Weiland D, Sutherland DER, Chaven B, Simmons RL, Ascher NL, Najarian JS. Information on 628 living-related kidney donors at a single institution, with long-term follow-up in 472 cases. Transplant Proc. 1984;16:655. |

| 32. | Shirasaki Y, Tsushima T, Nasu Y, Kumon H. Long-term consequence of renal function following nephrectomy for renal cell cancer. Int J Urol. 2004;11:704-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Meyer JP, Delves GH, Sullivan ME, Keoghane SR. The effect of nephroureterectomy on glomerular filtration rate. BJU Int. 2006;98:845-848. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Kaag M, Trost L, Thompson RH, Favaretto R, Elliott V, Shariat SF, Maschino A, Vertosick E, Raman JD, Dalbagni G. Preoperative predictors of renal function decline after radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. BJU Int. 2014;114:674-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 2007; . |

| 36. | Pak RW, Moskowitz EJ, Bagley DH. What is the cost of maintaining a kidney in upper-tract transitional-cell carcinoma? An objective analysis of cost and survival. J Endourol. 2009;23:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sayin A, Mutluay R, Sindel S. Quality of life in hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and transplantation patients. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:3047-3053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zincke H, Neves RJ. Feasibility of conservative surgery for transitional cell cancer of the upper urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am. 1984;11:717-724. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Schmeller NT, Hofstetter AG. Laser treatment of ureteral tumors. J Urol. 1989;141:840-843. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Andersen JR, Kristensen JK. Ureteroscopic management of transitional cell tumors. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1994;28:153-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gaboardi F, Bozzola A, Dotti E, Galli L. Conservative treatment of upper urinary tract tumors with Nd: YAG laser. J Endourol. 1994;8:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Engelmyer EI, Belis JA. Long-term ureteroscopic management of low-grade transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Tech Urol. 1996;2:113-116. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Daneshmand S, Quek ML, Huffman JL. Endoscopic management of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: long-term experience. Cancer. 2003;98:55-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Matsuoka K, Lida S, Tomiyasu K, Inoue M, Noda S. Transurethral endoscopic treatment of upper urinary tract tumors using a holmium: YAG laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2003;32:336-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Iborra I, Solsona E, Casanova J, Ricós JV, Rubio J, Climent MA. Conservative elective treatment of upper urinary tract tumors: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for recurrence and progression. J Urol. 2003;169:82-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Johnson GB, Grasso M. Ureteroscopic management of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Urol. 2005;15:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Rouprêt M, Hupertan V, Traxer O, Loison G, Chartier-Kastler E, Conort P, Bitker MO, Gattegno B, Richard F, Cussenot O. Comparison of open nephroureterectomy and ureteroscopic and percutaneous management of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 2006;67:1181-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Reisiger K, Hruby G, Clayman RV, Landman J. Office-based surveillance ureteroscopy after endoscopic treatment of transitional cell carcinoma: technique and clinical outcome. Urology. 2007;70:263-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Krambeck AE, Thompson RH, Lohse CM, Patterson DE, Segura JW, Zincke H, Elliott DS, Blute ML. Endoscopic management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma in patients with a history of bladder urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177:1721-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Painter DJ, Denton K, Timoney AG, Keeley FX. Ureteroscopic management of upper-tract urothelial cancer: an exciting nephron-sparing option or an unacceptable risk? J Endourol. 2008;22:1237-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lucas SM, Svatek RS, Olgin G, Arriaga Y, Kabbani W, Sagalowsky AI, Lotan Y. Conservative management in selected patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma compares favourably with early radical surgery. BJU Int. 2008;102:172-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Cornu JN, Rouprêt M, Carpentier X, Geavlete B, de Medina SG, Cussenot O, Traxer O. Oncologic control obtained after exclusive flexible ureteroscopic management of upper urinary tract urothelial cell carcinoma. World J Urol. 2010;28:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Gadzinski AJ, Roberts WW, Faerber GJ, Wolf JS. Long-term outcomes of nephroureterectomy versus endoscopic management for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2010;183:2148-2153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cutress ML, Stewart GD, Wells-Cole S, Phipps S, Thomas BG, Tolley DA. Long-term endoscopic management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: 20-year single-centre experience. BJU Int. 2012;110:1608-1617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Grasso M, Fishman AI, Cohen J, Alexander B. Ureteroscopic and extirpative treatment of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: a 15-year comprehensive review of 160 consecutive patients. BJU Int. 2012;110:1618-1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Fajkovic H, Klatte T, Nagele U, Dunzinger M, Zigeuner R, Hübner W, Remzi M. Results and outcomes after endoscopic treatment of upper urinary tract carcinoma: the Austrian experience. World J Urol. 2013;31:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Chen GL, Bagley DH. Ureteroscopic management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma in patients with normal contralateral kidneys. J Urol. 2000;164:1173-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Tasca A, Zattoni F. The case for a percutaneous approach to transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. J Urol. 1990;143:902-904; discussion 904-905. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Fuglsig S, Krarup T. Percutaneous nephroscopic resection of renal pelvic tumors. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1995;172:15-17. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Plancke HR, Strijbos WE, Delaere KP. Percutaneous endoscopic treatment of urothelial tumours of the renal pelvis. Br J Urol. 1995;75:736-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Patel A, Soonawalla P, Shepherd SF, Dearnaley DP, Kellett MJ, Woodhouse CR. Long-term outcome after percutaneous treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. J Urol. 1996;155:868-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Clark PE, Streem SB, Geisinger MA. 13-year experience with percutaneous management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1999;161:772-775; discussion 775-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Goel MC, Mahendra V, Roberts JG. Percutaneous management of renal pelvic urothelial tumors: long-term followup. J Urol. 2003;169:925-929; discussion 929-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Rouprêt M, Traxer O, Tligui M, Conort P, Chartier-Kastler E, Richard F, Cussenot O. Upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: recurrence rate after percutaneous endoscopic resection. Eur Urol. 2007;51:709-713; discussion 714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Rastinehad AR, Ost MC, Vanderbrink BA, Greenberg KL, El-Hakim A, Marcovich R, Badlani GH, Smith AD. A 20-year experience with percutaneous resection of upper tract transitional carcinoma: is there an oncologic benefit with adjuvant bacillus Calmette Guérin therapy? Urology. 2009;73:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Palou J, Piovesan LF, Huguet J, Salvador J, Vicente J, Villavicencio H. Percutaneous nephroscopic management of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: recurrence and long-term followup. J Urol. 2004;172:66-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |