Published online Mar 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i1.101480

Revised: November 29, 2024

Accepted: January 7, 2025

Published online: March 25, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 15.3 Hours

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an incapacitating illness associated with distressing symptoms (DS) that have negative impact on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

To assess the severity of DS and their relationships with HRQOL among patients with CKD in Jordan.

A descriptive cross-sectional design was used. A convenience sampling approach was used to recruit the participants. Patients with CKD (n = 140) who visited the outpatient clinics in four hospitals in Amman between November 2021 and December 2021 were included.

The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System was used to measure the severity of the DS while the Short Form-36 tool was used to measure the HRQOL. Parti

Patients with CKD had suboptimal HRQOL, physically and mentally. They suffer from multiple DS that have a strong association with diminished HRQOL such as tiredness and depression. Therefore, healthcare providers should be equipped with the essential knowledge and skills to promote individualized strategies that focusing on symptom management.

Core Tip: This study examines distressing symptoms (DS) and their effect on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in 140 patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale and the Short Form-36 were used. The results reveal that tiredness and worse well-being are the most severe symptoms. Physical health scores (48.50) are notably lower than mental health scores (58.24). Negative correlations exist between DS (e.g., depression, tiredness) and HRQOL, emphasizing the need for tailored symptom management. The study highlights the suboptimal HRQOL in CKD patients and recommends interdisciplinary care and further research for effective symptom management strategies.

- Citation: Abdalrahim M, Al-Sutari M. Distressing symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(1): 101480

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i1/101480.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i1.101480

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive disease with high morbidity and mortality rates among adults with diabetes, hypertension, and pre-existing acute kidney injury[1]. It is defined as a loss of kidney function with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2[2]. Globally, the burden of CKD counts is approximately 10% of adults and caused 1.2 million deaths in 2017, where it was considered the 12th leading cause of death worldwide[3]. In Jordan, by the end of 2020, the total number of patients with CKD registered in the Jordan Renal Registry was 7747, of which 975 were new cases[4]. However, these figures only reflect the registered confirmed cases, leaving a high proportion of Jordanian cases that are underdiagnosed and unrecognized[5].

For those with confirmed CKD, prevention of complications and recognition of disturbing symptoms are crucial actions to be considered[2]. Patients with CKD frequently experience significant distressing symptoms (DS) that considerably affect their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and requires supportive and palliative care[6]. The aim of supportive and palliative care is to relieve DS and improve HRQOL which requires interdisciplinary team care with united decisions[7]. However, patients’ free choice and wishes should be taken into account without constraints when planning their health care[8].

Patients with CKD experience a variety of physical and mental symptoms[9]. These symptoms worsen during under

In conclusion, there is a lack of evidence on the assessment of the prevalence of DS among patients with CKD that leads to ineffective management. Ineffective symptoms management may lead to excessive suffering, decreased ability to cope with the disease, interference with activities of daily living, dissatisfaction with health condition, and recurrent or prolonged hospitalization[2]. Consequently, further studies are needed to evaluate the severity of DS and their effects on HRQOL among patients with CKD, and thus, help form the basis for future research that investigate the adequacy of symptom management programs. Therefore, the purposes of the study were to assess the severity of DS among patients with CKD and to evaluate the relationship between DS and HRQOL among these patients in Jordan.

A descriptive cross-sectional design was conducted using self-report questionnaires and review of patients’ medical files. Data were collected over a three months’ period, from November to December 2021.

The G* Power 3.1.9.7 software was used to determine the required sample size considering the following criteria: Power of 0.8, medium effect size of 0.15, and alpha level of 0.05, for multiple linear regression with nine predictors[13]. Accordingly, the sample size needed was 117 participants. To compensate for the anticipated missing data, approximately 20% (23) participants were added. Thus, a total of 140 participants were included in the study. Patients who met the following inclusion criteria were recruited: (1) Age 18 or above; and (2) Diagnosed with CKD as documented in the medical record by the attending nephrologists. Patients with cognitive impairment, sever illness, or general frailty have been excluded because these conditions may have impact on the participants’ HRQOL.

The participants were recruited from four large hospitals in Jordan: Two from the governmental sector and two from the private sector. The capacity of each hospital ranges from 350-500 beds. Data was collected while patients were waiting for their turn in the outpatients’ nephrology clinics.

Participants’ characteristics such as medical diagnosis, age, gender, marital status, level of education, comorbid conditions, and employment status were taken from patients’ medical files. The Arabic version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) was used to assess the severity of DS originally developed by Hui and Bruera[14] in 2017. The ESAS comprises of nine items that assess DS severity including: Pain, tiredness, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, well-being, and shortness of breath. Participants rated the severity of each DS over the past 24 hours using a scale ranging from 0 to 10; (0 = no symptom and 10 = worst possible severity). The Arabic ESAS has been confirmed to be reliable (α = 0.844), and had a discriminant validity of 87.8%, and a convergent validity of 0.40 (100%)[15].

To measure the patients’ HRQOL, the RAND-36 tool was used which was originally developed by Ware and Gandek[16] in 1998. The SF-36 consists of two main dimensions: The physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS). The PCS includes 10 items related to physical functioning: Role limitations due to physical health (4 items), bodily pain (2 items), and general health perception (5 items). The MCS includes energy/vitality (4 items), social functioning (2 items), role limitations due to emotional problems (3 items), and mental health (5 items). Each domain was given a score out of 100 that indicating the highest possible HRQOL.

Scoring of the RAND-36 scale items involves linearly transforming each item so that the lowest and highest possible scores were set at 0 and 100; with higher scores indicating the higher level of HRQOL. The scoring followed a two-step process. First, the numeric values were coded according to the scoring key. Second, the scale items were averaged together to create the eight scale scores (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Participants were asked to rate the scale items of HRQOL according to their condition in the last month of data collection date. The SF-36 questionnaire showed good reliability with a Cronbach alpha of 0.8 and test-retest reliability revealed a strong association between pre-scores and post-scores (PCC = 0.873)[17]. In this study, the SF-36 questionnaire had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.82.

Ethical approvals to conduct the study were attained from the Academic Research Committee at the School of Nursing (IRB No. PMs.19.6). Each participant signed the informed consent form prior to completing the questionnaires. Parti

Analysis of the study data were done using IBM SPSS software version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Data were screened for missing values, outliers, and inconsistencies to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the subsequent analyses. Participants’ characteristics, scores of the ESAS questionnaire, and scores of the SF-36 questionnaire were analyzed using the means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages. To assess the association between DS burden and the PCS and MCS, Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used. A two-tail test, and alpha = 0.05 was used for all the tests.

Of the 150 patients with CKD who were approached, 140 patients completed the questionnaires with a response rate of 93.3%. Participants mean age was 50.9 (SD = 15.14). Most of the participants were males (n = 92, 65.7%), married (n = 95, 67.9%), and unemployed (n = 93, 66.4%). Two- thirds of the participants had comorbidities (n = 68, 48.6%). Participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Variable | n (%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 92 (65.7) |

| Female | 48 (34.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 95 (67.9) |

| Not married | 45 (32.1) |

| Education status | |

| Elementary education or below | 25 (17.9) |

| Secondary | 58 (41.4) |

| Bachelor or higher | 57 (40.7) |

| Employment status | |

| Working | 47 (33.6) |

| Not working | 93 (66.4) |

| Smoking status | |

| Yes | 32 (22.9) |

| No | 108 (77.1) |

| Co morbidity status | |

| With other co-morbid disease | 68 (48.6) |

| Without other co-morbid disease | 72 (51.4) |

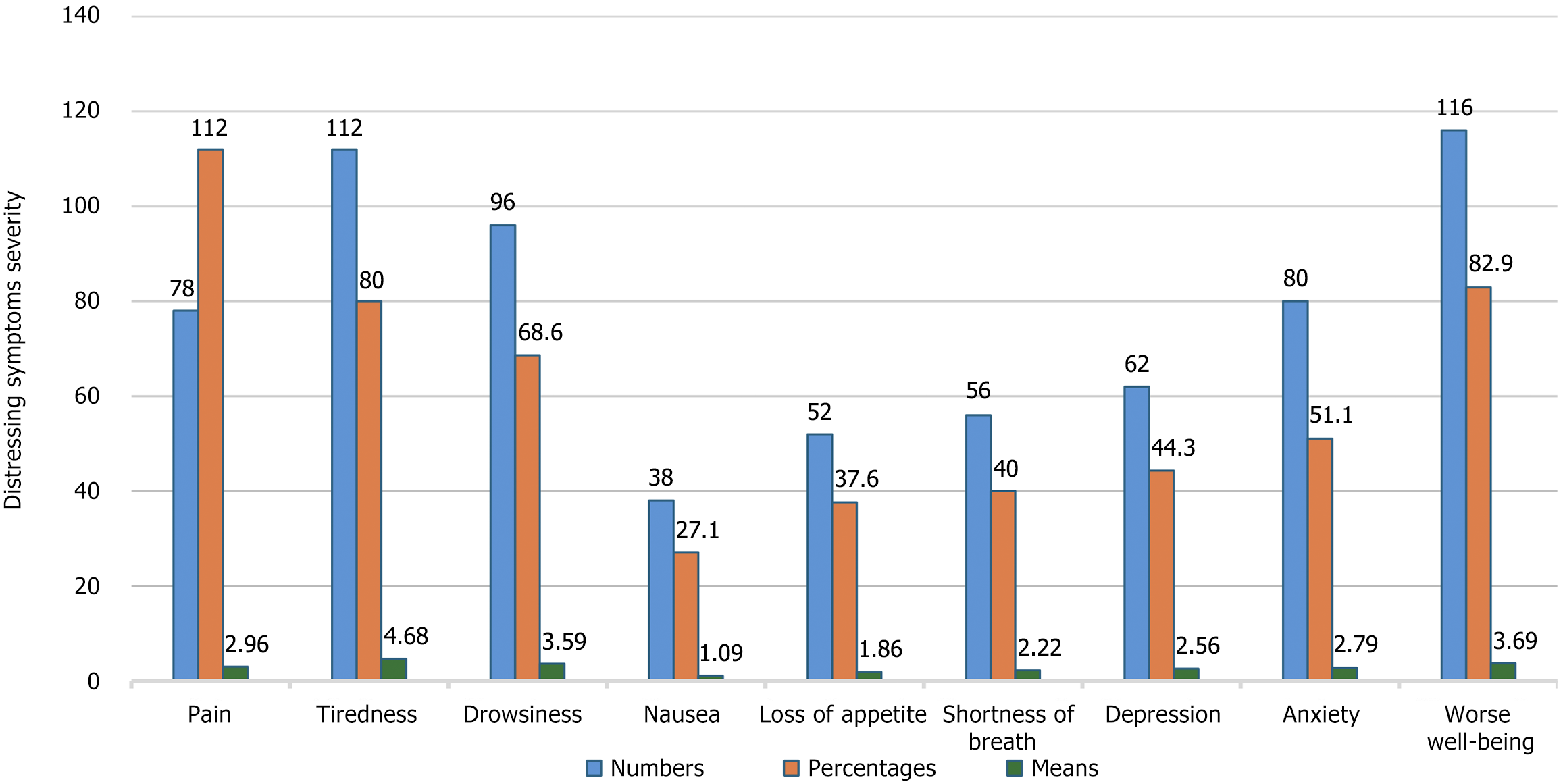

The severity of DS was measured using the ESAS questionnaire. The results revealed that tiredness (4.68 ± 2.98) and worse well-being (3.69 ± SD) were the most sever DS reported by the participants. However, nausea (1.09 ± SD) and loss of appetite (1.86 ± 2.82) were the least sever DS. Figure 1 presents descriptive statistics for the DS.

The results showed that the participants had a mean SF-36 score of 53.37 (± 17.58). The mean PCS score was 48.50 (± 18.30) and the mean MCS score was 58.24 (± 20.59). According to the SF-36 subscales, the results showed that the highest mean score was for the bodily pain scale with a mean score of 68.50 out of 100 (± 32.02) followed by the emotional well-being scale with a mean score of 67.60 (± 18.57). One the other hand, the role limitation due to physical health had the lowest mean score of 31.61 out of 100 (± 38.59). The mean total scores of the SF-36, PCS, and MCS are shown in Table 2.

| Subscales of Short Form-36 questionnaire | mean ± SD |

| Physical component summary | 48.50 ± 18.30 |

| Physical functioning | 48.12 ± 29.65 |

| Role limitation due to physical functioning | 31.61 ± 38.59 |

| Bodily pain | 68.50 ± 32.02 |

| General health perception | 45.79 ± 17.86 |

| Mental component summary | 58.24 ± 20.59 |

| Energy/vitality | 48.50 ± 18.72 |

| Social functioning | 60.18 ± 31.15 |

| Role limitation due to emotional functioning | 56.67 ± 46.41 |

| Mental health | 67.60 ± 18.57 |

| Total score of Short Form 36 | 53.37 ± 17.58 |

The PCS, the MCS and the SF-36 total score association with the DS were tested using Pearson correlation coefficient (r). The results showed that PCS was significantly and negatively correlated with tiredness, loss of appetite, shortness of breath, depression, and well-being. The highest association was found between PCS and tiredness (r = -0.47, P < 0.001). On the other hand, MCS was significantly and negatively associated with all DS except drowsiness. The highest association was between depression and MCS (r = 0.497, P < 0.001). SF-36 total score was negatively associated with all DS except drowsiness. The strongest association was between SF-36 total and tiredness (r = -0.53, P < 0001). Values of Pearson correlation coefficient for the associations between the ESAS symptoms and SF-36 domains are shown in Table 3.

| Variables | Pain | Tiredness | Drowsiness | Nausea | Loss of appetite | Shortness of breath | Depression | Anxiety | Worse well-being |

| Physical component summary | -0.44a | -0.47a | -0 .12 | -0.12a | -0.30a | 0.-9a | -0.23a | -0.14a | -0.38a |

| Mental component summary | -0.48a | -0.48a | -0.13 | -0.29a | -0.49a | 0-.38a | -0.49a | -0.42a | -0.37a |

| Total Short Form-36 scores | -0.37a | -0.53a | -0.14 | -0.23a | -0.44a | -0.37a | -0.41a | -0.32a | -0.42a |

Effective symptom management is the most important step in developing care plans for patients with chronic diseases such as CKD. This study assessed the severity of DS and their relationships with the HRQOL among patients with CKD in Jordan. In the current study, patients with CKD experienced multiple physical and psychological DS.

The results revealed that tiredness and worse well-being were the highest reported DS among patients with CKD. These results were consistent with a systemic review study involved 449 studies from 62 countries that aimed to investigate the symptom prevalence and severity in patients with CKD worldwide; the study found that fatigue was the most severely and frequently reported symptom[18]. Another study conducted in Seri Lanka found that lack of energy was one of the most prevalent physical symptoms among patients with CKD, along with pain and loss of appetite[19].

Not surprisingly fatigue was highly prevalent symptom in our study. There are several factors that cause fatigue among patients with CKD including changes in lifestyle, anemia, recurrent inflammations, and depression[20,21]. The pathophysiology of fatigue in patients with CKD is contributed by abnormalities in the laboratory values such as low calcium and high potassium levels, the presence of comorbidities such as heart diseases, lack of Oxygen supply to the tissue, and metabolic acidosis[22].

Feeling of well-being is a subjective symptom that reflects patients’ perception of their health and is mostly influenced by their optimistic or pessimistic attitude towards the disease and the challenges in their lives[23]. In our study, the results revealed that the worst well-being was the second most severe reported symptom among patients with CKD. Those patients may experience a combination of negative feelings such as anger, sadness and hopelessness that make them lose sources of optimism[24]. According to a cross-sectional study aimed to examine the associates of optimism and pessimism among Lebanese patients with CKD, body appreciation was associated with higher optimism because it strongly related to self-esteem and positive self-image[25].

Health-related quality of life is an important indicator of the patients’ health and well-being, effectiveness of treatment, and gives information about symptoms from patients’ perspective[26]. The results of our study revealed that the total mean score of patients’ HRQOL was nearly 53.4 with the PCS average score (48.50) lower than the MCS average score (58.24). In addition, the highest mean score was bodily pain followed by emotional well-being. While the lowest score was for the role limitation due to physical health. These findings were similar to Senanayake et al[27] study in 2020 in Sir Lanka that found the total score for HRQOL was (50.8), and PCS was lower than MCS with the highest score for bodily pain.

A possible reason for the higher MCS scores compared with PCS scores among patients with CKD might be related to Jordanian culture and family ties: Social support for patients is mainly common among those with chronic diseases. In addition, our study participants were Muslims; according to a systemic review that examined the association between religiosity and mental health in Islam, the study indicated that reading the Islamic holy book “Qur’an” and praying help patients to reduce the impact of stress and improve well-being[28].

According to the current study, there were many factors that may contribute to the decrease HRQOL among patients with CKD. For example, low economic status and unemployment could decrease access to optimal medical care in Jordan and eventually affect the patients’ HRQOL[27]. Additionally, many CKD patients suffer from multiple physical and psychological DS such as tiredness, lack of well-being, pain, drowsiness, and depression which impose negative impact on their HRQOL[27]. These problems will be aggravated if the patients are maintained on hemodialysis[29].

The results showed all DS were negatively associated with the overall HRQOL except drowsiness, which had the strongest association with tiredness. PCS was significantly and negatively associated with tiredness, loss of appetite, shortness of breath, depression, and well-being, with the highest association with tiredness. Patient with CKD described fatigue as prolonged tiredness and lack of energy that is manifested by muscle weakness and decreased mobility, leading to limitations in physical and social activity that led to loss of enjoyment in life[30].

The MCS was significantly and negatively associated with all the symptoms except drowsiness, which was most strongly associated with depression. These results were consistent with a study that reported that depression was significantly associated with lower HRQOL scores for both PCS and MCS among patients with CKD in Sir Lanka[27].

Depression is a common psychological problem among patients with CKD and has been shown to have the greatest impact on their HRQOL especially among those who are treated by hemodialysis[31]. In a cross-sectional study that investigated the prevalence of depression and its relationship with HRQOL among 1079 patients with CKD in China, the study found that 23% of them were developing depression and it was a significant predictor of all components of their HRQOL[32]. Accordingly, health care providers should take this high rate of depression into account and plan for proper management in advance.

The current study has some limitations that should be addressed. First, the DS were measured at one point in time using self- report questionnaires, which may miss some of accurate patients’ responses. Second, the current study did not include any objective measures to assess the severity of DS. The convenience sampling method is considered easy, applicable, and appropriate for research purposes, but this method may have a chance to produce sampling bias.

Patients with CKD had suboptimal HRQOL, both physically and mentally. They experienced multiple physical and psychological DS that were strongly associated with HRQOL. Some of these symptoms were found to be strongly associated with diminished HRQOL such as tiredness and depression. Consequently, health-care should focus on routine assessment of DS among patients with CKD. Health care providers should be equipped with the essential knowledge and skills to anticipate the burden of symptoms on patient’s HRQoL by promoting individualized strategies focused on symptoms management. The results explored the presence and severity of DS among patients with CKD and their negative impact on all domains of HRQOL. Thus, there is a need to develop institutional programs and develop national and international guidelines for comprehensive assessment and management of DS and develop a policy to improve standards to enhance HRQOL for patients with CKD. Additional research is needed to examine the effects of educational programs for patients with CKD and their families. The programs may focus on self-care management of DS.

| 1. | Abdalrahim MS, Khalil AA, Alramly M, Alshlool KN, Abed MA, Moser DK. Pre-existing chronic kidney disease and acute kidney injury among critically ill patients. Heart Lung. 2020;49:626-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1238-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1654] [Cited by in RCA: 2417] [Article Influence: 302.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395:709-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3928] [Cited by in RCA: 3775] [Article Influence: 755.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saleh WW. Non-Communicable Disease Directorate National Registry of End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). 12th Annual Report. 2019. [cited 18 June 2024]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.jo/ebv4.0/root_storage/en/eb_list_page/12th_annual_report_esrd_2019.pdf. |

| 5. | Khalil AA, Abed MA, Ahmad M, Mansour AH. Under-diagnosed chronic kidney disease in Jordanian adults: prevalence and correlates. J Ren Care. 2018;44:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Jafar TH, Nitsch D, Neuen BL, Perkovic V. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2021;398:786-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 756] [Article Influence: 189.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Siriwardana AN, Hoffman AT, Brennan FP, Li K, Brown MA. Impact of Renal Supportive Care on Symptom Burden in Dialysis Patients: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:725-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Wightman A, Liao S. Ensuring Choice for People with Kidney Failure - Dialysis, Supportive Care, and Hope. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:99-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lockwood MB, Rhee CM, Tantisattamo E, Andreoli S, Balducci A, Laffin P, Harris T, Knight R, Kumaraswami L, Liakopoulos V, Lui SF, Kumar S, Ng M, Saadi G, Ulasi I, Tong A, Li PK. Patient-centred approaches for the management of unpleasant symptoms in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:185-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Muflih S, Alzoubi KH, Al-Azzam S, Al-Husein B. Depression symptoms and quality of life in patients receiving renal replacement therapy in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;66:102384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yapa HE, Purtell L, Chambers S, Bonner A. The Relationship Between Chronic Kidney Disease, Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. J Ren Care. 2020;46:74-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nabolsi MM, Wardam L, Al-Halabi JO. Quality of life, depression, adherence to treatment and illness perception of patients on haemodialysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26400] [Cited by in RCA: 34859] [Article Influence: 1936.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 Years Later: Past, Present, and Future Developments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:630-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 65.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shamieh O, Alarjeh G, Qadire MA, Amin Z, AlHawamdeh A, Al-Omari M, Mohtadi O, Illeyyan A, Ayaad O, Al-Ajarmeh S, Al-Tabba A, Ammar K, Al-Rimawi D, Abu-Nasser M, Abu Farsakh F, Hui D. Validation of the Arabic Version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ware JE Jr, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:903-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1606] [Cited by in RCA: 1752] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | El-Kalla M, Abd El-Khalek Khalaf MM, Saad MAA, Othman EM. Reliability of the Arabic Egyptian Version of Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire to Measure Quality of Life in Burned Patient. Med J Cairo Univ. 2016;84:311-316. |

| 18. | Fletcher BR, Damery S, Aiyegbusi OL, Anderson N, Calvert M, Cockwell P, Ferguson J, Horton M, Paap MCS, Sidey-Gibbons C, Slade A, Turner N, Kyte D. Symptom burden and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2022;19:e1003954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abeywickrama HM, Wimalasiri S, Koyama Y, Uchiyama M, Shimizu U, Kakihara N, Chandrajith R, Nanayakkara N. Quality of Life and Symptom Burden among Chronic Kidney Disease of Uncertain Etiology (CKDu) Patients in Girandurukotte, Sri Lanka. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Debnath S, Rueda R, Bansal S, Kasinath BS, Sharma K, Lorenzo C. Fatigue characteristics on dialysis and non-dialysis days in patients with chronic kidney failure on maintenance hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zalai D, Bohra M. Fatigue in chronic kidney disease: Definition, assessment and treatment. CANNT J. 2016;26:39-44. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gregg LP, Bossola M, Ostrosky-Frid M, Hedayati SS. Fatigue in CKD: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16:1445-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schiavon CC, Marchetti E, Gurgel LG, Busnello FM, Reppold CT. Optimism and Hope in Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review. Front Psychol. 2016;7:2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de Sousa LMM, Antunes AV, Baixinho CRSL, Severino SSP, Marques-Vieira CMA, José HMG. Subjective wellbeing assessment in people with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis. Subjective Wellbeing Assessment in People with Chronic Kidney Disease Undergoing Hemodialysis. In: Rath T. Chronic Kidney Disease - from Pathophysiology to Clinical Improvements. Croácia: InTech, 2018: 281-293. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Hajj-Moussa M, El Hachem N, El Sebaaly Z, Moubarak P, Kahwagi RM, Malaeb D, Hallit R, El Khatib S, Hallit S, Obeid S, Fekih-Romdhane F. Body appreciation is associated with optimism/pessimism in patients with chronic kidney disease: Results from a cross-sectional study and validation of the Arabic version of the Optimism-Pessimism Short Scale-2. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0306262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:645-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 633] [Cited by in RCA: 867] [Article Influence: 96.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Senanayake S, Gunawardena N, Palihawadana P, Senanayake S, Karunarathna R, Kumara P, Kularatna S. Health related quality of life in chronic kidney disease; a descriptive study in a rural Sri Lankan community affected by chronic kidney disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Koenig HG, Al Shohaib SS. Religiosity and Mental Health in Islam. In: Moffic H, Peteet J, Hankir A, Awaad R. Islamophobia and Psychiatry. Springer: Cham, 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Pretto CR, Winkelmann ER, Hildebrandt LM, Barbosa DA, Colet CF, Stumm EMF. Quality of life of chronic kidney patients on hemodialysis and related factors. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2020;28:e3327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jaime-Lara RB, Koons BC, Matura LA, Hodgson NA, Riegel B. A Qualitative Metasynthesis of the Experience of Fatigue Across Five Chronic Conditions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59:1320-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kunwar D, Kunwar R, Shrestha B, Amatya R, Risal A. Depression and Quality of Life among the Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2020;18:459-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang WL, Liang S, Zhu FL, Liu JQ, Wang SY, Chen XM, Cai GY. The prevalence of depression and the association between depression and kidney function and health-related quality of life in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:905-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |