Published online Dec 25, 2024. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v13.i4.98932

Revised: September 28, 2024

Accepted: October 21, 2024

Published online: December 25, 2024

Processing time: 120 Days and 20.8 Hours

Kidney function loss or renal insufficiency indicated by elevated creatinine levels and/or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/minute/1.73 m² at presentation in patients with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is commonly seen as a poor prognostic marker for kidney survival. However, a pre>vious study from our center suggested this may be due to hemodynamic fac

To observe the clinical and biochemical parameters, treatment response, kidney survival, and overall outcomes of adult patients with primary FSGS presenting with kidney function insufficiency.

This retrospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Neph

Among the 98 patients with renal function loss on presentation, the mean age was 30.9 years ± 13.6 years with a male-to-female ratio of 2.5:1. The mean serum creatinine level was 2.2 mg/dL ± 1.3 mg/dL and mean eGFR 37.1 mL/minu

Renal function loss in FSGS patients at presentation does not necessarily indicate irreversible kidney function loss and a significant number of patients respond to appropriate treatment of the underlying disease.

Core Tip: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is a common glomerular disease that typically presents with nephrotic syndrome. It often presents with kidney function loss and generally signifies a poor prognosis. We previously showed that kidney function loss at presentation is not necessarily associated with poor outcomes. This study further corroborates these findings and suggests that treatment of such patients can improve outcomes.

- Citation: Jafry NH, Sarwar S, Waqar T, Mubarak M. Clinical course and outcome of adult patients with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with kidney function loss on presentation. World J Nephrol 2024; 13(4): 98932

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v13/i4/98932.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v13.i4.98932

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a clinicopathological syndrome characterized by variable levels of proteinuria (usually in the nephrotic range) and histopathologically by focal and segmental scarring of glomeruli, along with effacement of foot processes[1]. First described in 1957 by Rich in an autopsy series, FSGS is a common cause of nephrotic syndrome (NS), accounting for 40% of primary glomerulonephritis cases among adults and the second most common cause of NS in the pediatric population. The estimated incidence of FSGS in adults is approximately 7 per million population per year. The incidence varies by region and population demographics, with higher rates observed in certain ethnic groups, such as African Americans compared to Caucasians[2,3].

Over the past decade, the number of patients with FSGS has increased, making it the most frequent primary glomerulopathy leading to end-stage kidney disease[4,5]. Male sex, elevated creatinine levels or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/minute/1.73 m², and advanced stages of tubulointerstitial fibrosis at presentation are generally considered poor prognostic markers for kidney survival[6,7]. However, our previous study suggested that elevated serum creatinine was likely due to hemodynamic factors leading to reduced eGFR rather than chronic changes, and thus, increased serum creatinine levels alone did not adversely affect the outcome[8].

Despite recent advancements in the treatment of FSGS, including sodium-glucose transporter-2 inhibitors, angiotensin II/endothelin 2 receptor antagonists (Sparsentan), and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (Rituximab), prognosis still largely depends on baseline kidney function, the degree of global glomerulosclerosis, and the extent of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. A study showed that only 23.8% of patients with kidney function insufficiency (serum creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dL) achieved remission compared to 60% with normal kidney function[9,10]. Our previous publications indicated that elevated serum creatinine at presentation was not predictive of steroid responsiveness, suggesting that nephrologists should not be deterred from initiating steroid treatment, particularly in patients with a short duration of illness. Kidney function insufficiency is not a contraindication to treatment, as we have successfully treated many patients with steroids, resulting in either a decline or stabilization of serum creatinine levels[8].

This study aimed to observe the clinicopathological parameters and outcomes of adult patients with kidney function insufficiency at presentation in primary FSGS, assess their response to steroids, evaluate kidney survival, and describe the experiences from our center.

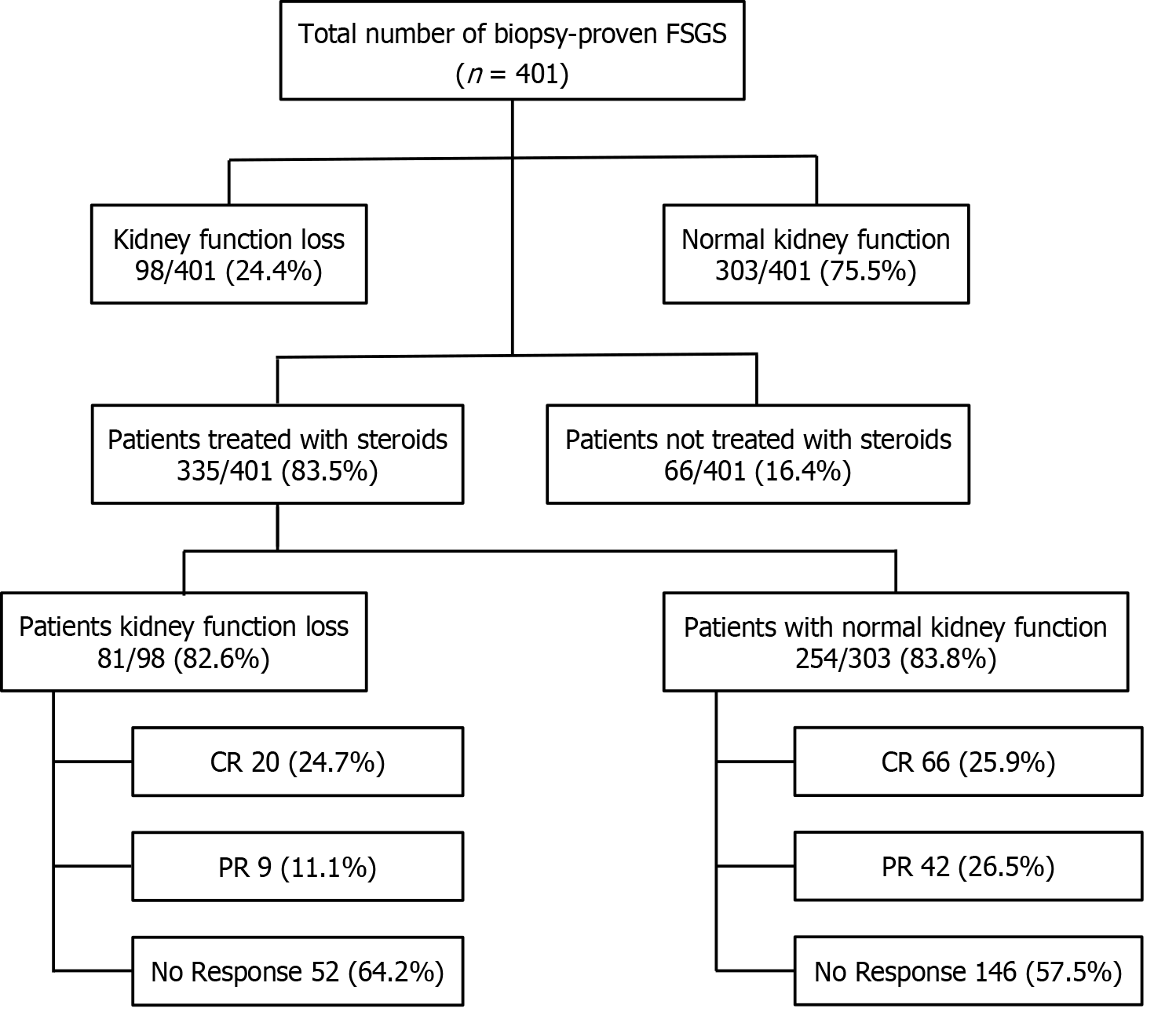

This retrospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Nephrology, Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT), Karachi, Pakistan, between January 1995 and December 2017. During this period, a total of 401 patients were diagnosed with primary FSGS. Among these, 98 (24.4%) patients had renal insufficiency or kidney function loss at presentation and were included in this study for detailed analysis. The majority of these patients, 81/98 (82.6%) were treated with steroids, as were 254/303 (83.8%) in those with normal renal function at presentation, as shown in Figure 1. The remaining few patients in both groups were treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) only.

The retrospective review included all consecutive adult patients (aged ≥ 17 years) with renal insufficiency who presented to the adult nephrology clinic of SIUT with a final diagnosis of primary FSGS and had at least 6 months of regular follow-up. Patients with known secondary causes of FSGS, including systemic diseases with glomerular involvement, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, intravenous heroin abuse, solitary kidney, and urinary obstruction and/or reflux, were excluded.

The original biopsy reports and clinical records were reviewed to determine the patients’ age, sex, degree of pro

The clinical course, treatment responses, and final outcomes of each patient were evaluated by recording current medications, BP, serum creatinine and serum albumin levels, urine analysis, and 24-hour urinary protein excretion or spot urine for protein-creatinine ratio at appropriate follow-up visits.

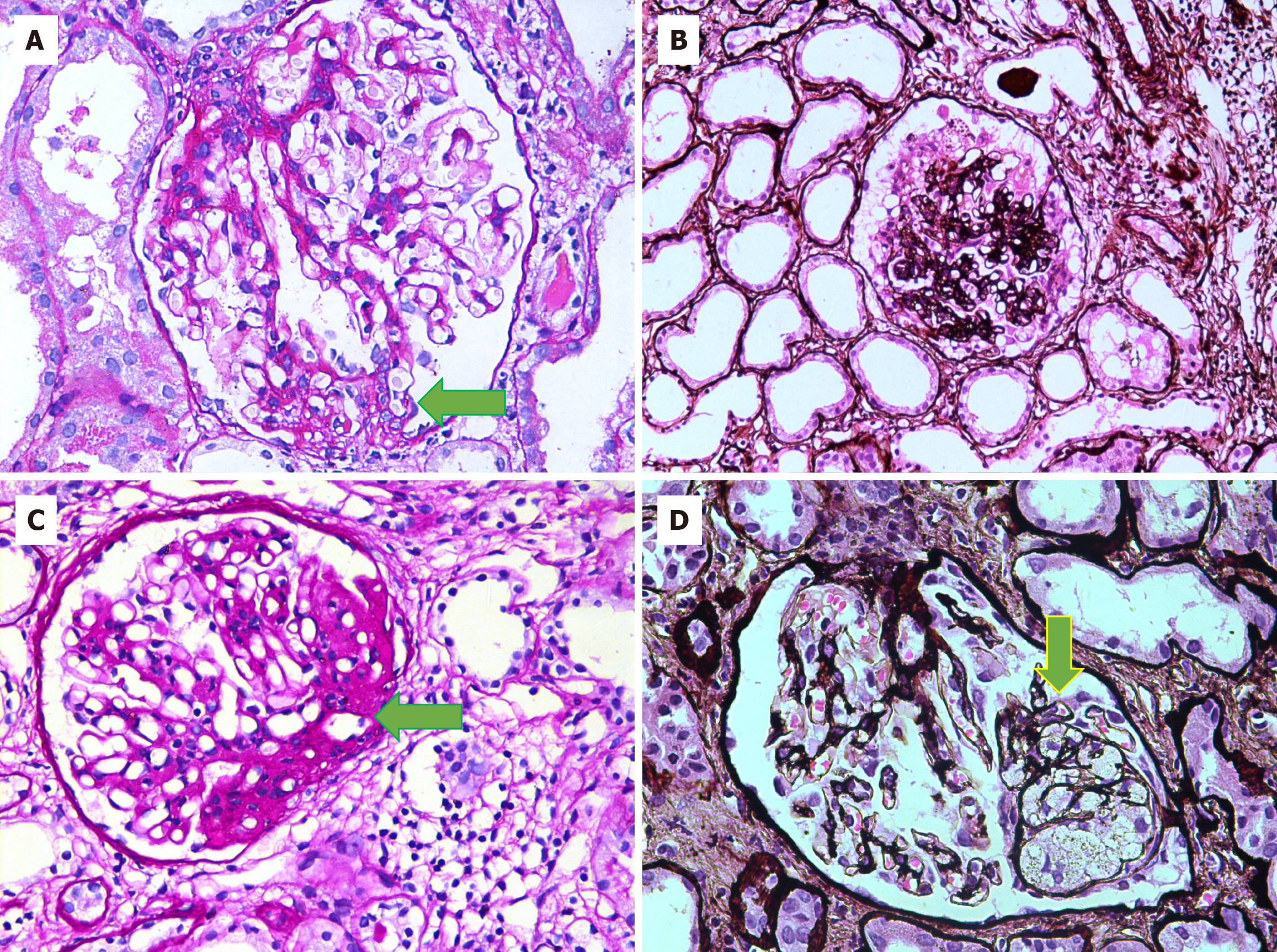

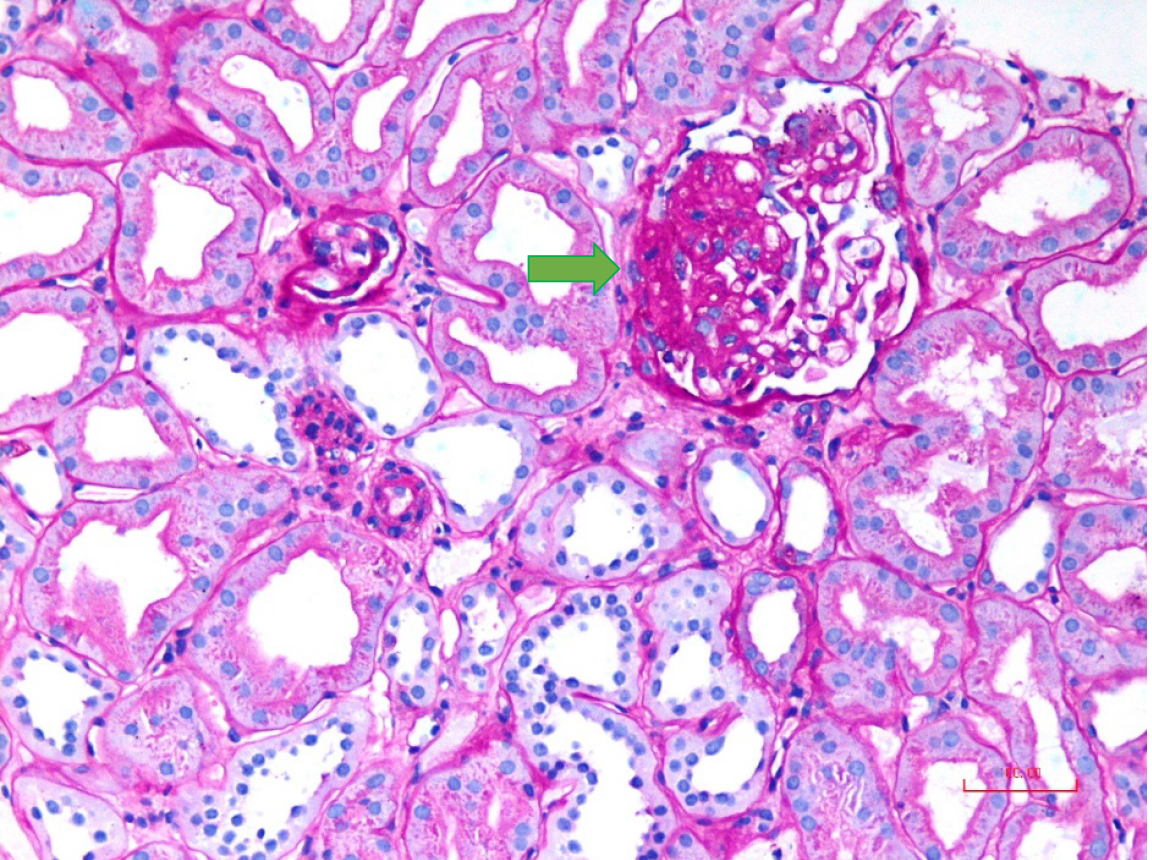

All patients underwent percutaneous native kidney biopsies under real-time ultrasound guidance after informed consent. Light microscopy was performed with 10 serial sections, with levels 1, 5, and 10 stained by hematoxylin and eosin stain, level 7 by trichrome, level 8 by periodic acid-Schiff, and level 9 by Jones methenamine silver stain. FSGS was diagnosed according to established criteria by two experienced renal pathologists independently and then jointly to reach a consensus diagnosis[11]. The histological variants of FSGS were classified per the Columbia classification criteria[12]. In brief, the tip variant was diagnosed when at least one segmental lesion involved the tip location of the affected glomerulus (outer 25% of the tuft next to the beginning of the proximal tubule) (Figure 2A). It required the exclusion of collapsing and perihilar variants. The tubular pole needs to be identified in the defining lesion. The collapsing variant was diagnosed when at least one glomerulus showed segmental or global collapse and overlying podocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia (Figure 2B). The defining criteria for perihilar variant included both of the following: (1) There must be at least one glomerulus with perihilar hyalinosis and/or sclerosis; and (2) > 50% of glomeruli with segmental lesions must have perihilar sclerosis and/or hyalinosis (Figure 2C). This category requires that the cellular variant, tip variant, and collapsing variant of FSGS be excluded. The cellular variant was defined by the presence of at least one glomerulus with endocapillary hypercellularity involving at least 25% of the tuft and causing obliteration of the capillary lumina (Figure 2D). Any segment (perihilar and/or peripheral) may be affected. This category requires that the tip variant and collapsing variant be excluded. FSGS, not otherwise specified (NOS), was diagnosed when at least one glomerulus revealed a segmental increase in the mesangial matrix obliterating the capillary lumina, with or without segmental capillary wall collapse but without associated podocyte hyperplasia (Figure 3). It required the exclusion of perihilar, cellular, tip, and collapsing variants.

Immunofluorescence tissue specimens were stained using FITC-conjugated antisera specific for immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), as detailed in our earlier report[11]. Electron microscopy was performed on kidney biopsy specimens in selected patients.

NS was diagnosed according to standard criteria[8]. Hypertension was defined as BP readings exceeding 140 mmHg for systolic BP and 90 mmHg for diastolic BP in two consecutive measurements in the supine and sitting positions, or the need for antihypertensive drugs. Kidney function loss at presentation was defined per Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2024 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as an eGFR < 60 mL/minute/1.73 m² in both sexes[13].

Standard therapeutic regimens and response definitions, with slight modifications, were used as in our previous study[11]. Briefly, all eligible patients were treated with prednisone at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight per day for 6 weeks, followed by 0.75 mg/kg per day for 6 additional weeks, which was then gradually tapered over 3 months to complete 6 months of treatment. Complete remission (CR) was defined as a decrease in the rate of proteinuria to ≤ 0.2 g/day for at least 1 month, with serum creatinine persistently < 1.4 mg/dL. Partial remission (PR) was defined as a decrease in the rate of urinary protein excretion to between 0.21 g/day and 2 g/day for at least 1 month, with serum creatinine < 1.4 mg/dL. Time to remission was calculated from the date of treatment administration to the date of remission. Relapse was defined as the recurrence of nephrotic-range proteinuria and edema during steroid tapering or after stopping treatment. Relapses received a second course of steroid treatment in combination with cyclosporine. Kidney failure (KF) and KF with replacement therapy (referred to as KFRT) were defined per standard criteria[8].

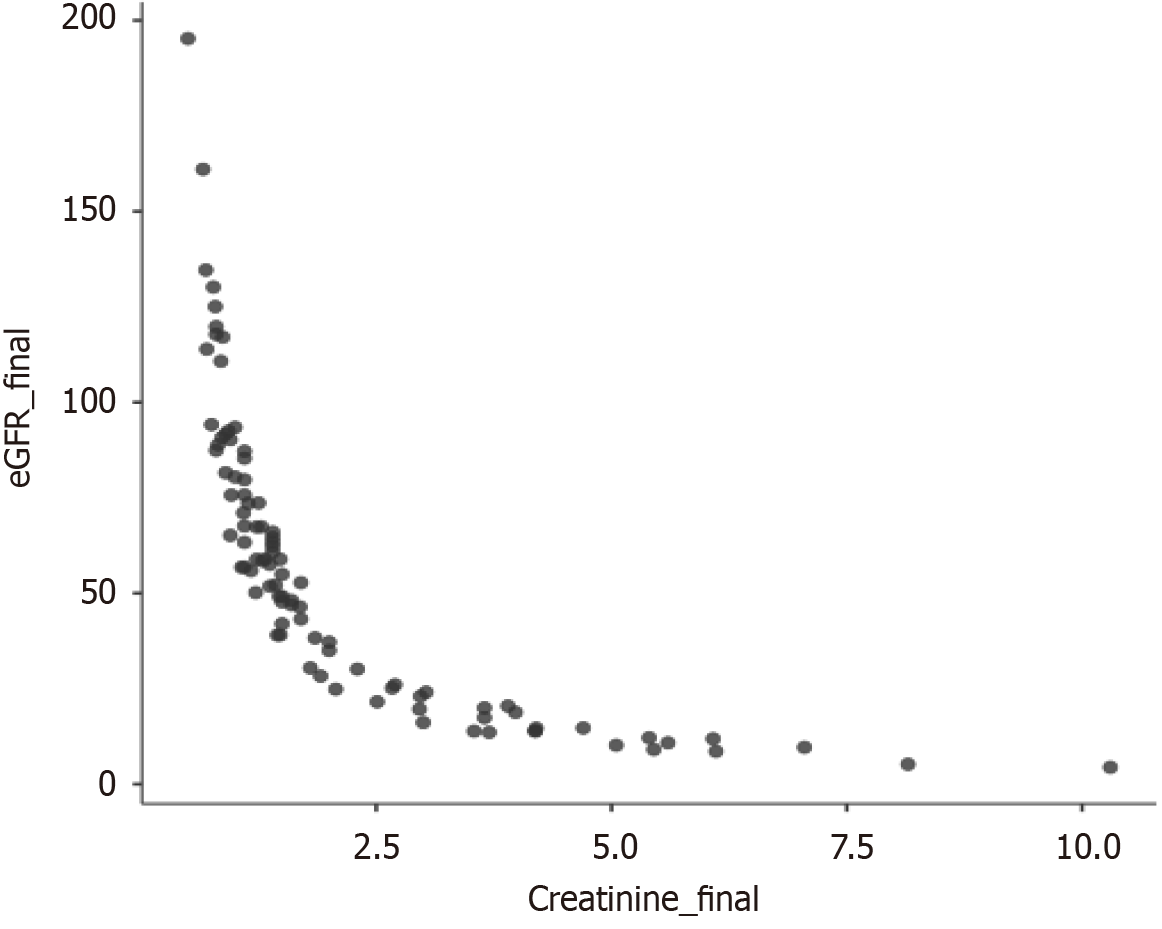

Data were entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive statistics summarized the continuous and categorical variables. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, depending on the data distribution. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. The χ² test was used to determine the proportion differences between the study groups for categorical variables. A student’s two-sample t-test was used to compare mean differences between treatment-responsive and treatment-resistant cases for continuous variables. Pearson’s correlation was used to find relationships, if any, between renal function loss and other clinical and laboratory findings at presen

A total of 401 biopsy-proven FSGS patients were identified during the study period, of which 98 (24.4%) had renal function loss at the time of presentation. The relevant baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 30.9 years ± 13.6 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.5:1. The mean serum creatinine level was 2.2 mg/dL ± 1.3 mg/dL and mean eGFR 37.1 mL/minute/1.73 m2 ± 12.8 mL/minute/1.73 m2. The mean 24-hour urinary protein excretion was 5.9 g/day ± 4.0 g/day. The mean serum albumin level was 2.1 g/dL ± 1.0 g/dL (median: 1.5 g/dL). The mean systolic BP was 132.7 mmHg ± 19.8 mmHg, and the mean diastolic BP was 87.4 mmHg ± 12.7 mmHg.

| Parameters | Results |

| Age in years | 30.9 ± 13.6 |

| Sex as male:female | 2.5:1 |

| Systolic BP in mmHg | 132.7 ± 19.8 |

| Diastolic BP in mmHg | 87.4 ± 12.7 |

| Initial proteinuria in mg/24 hours | 5945.1 ± 4007.9 |

| Serum albumin in g/dL | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

| Serum creatinine in mg/dL | 2.2 ± 1.3 |

| Renal insufficiency in males | 70 (71.4) |

| Renal insufficiency in females | 28 (28.6) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate on presentation in mL/minute/1.73 m2 | 37.1 ± 12.8 |

| Histopathological findings | |

| Number of glomeruli | 16.4 ± 8.2 |

| Number of glomeruli with global sclerosis | 3.4 ± 2.9 |

| Number of glomeruli with segmental sclerosis | 3.1 ± 3.0 |

| Tubular atrophy | |

| Mild | 41 (41.8) |

| Moderate | 11 (11.2) |

| Fibrointimal thickening of arteries | |

| Mild | 9 (4.2) |

| Moderate | 4 (4.1) |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis variants | |

| Not otherwise specified | 43 (43.9) |

| Tip | 20 (20.4) |

| Collapsing | 19 (19.4) |

| Hilar | 1 (1.0) |

| Cellular | 1 (1.0) |

| Unknown/unclassified | 14 (14.3) |

The relative percentages of FSGS variants were 44% for NOS, 20.4% for tip, 19.4% for collapsing, 1% for hilar, 1% for cellular, and 14.3% were unclassified/unknown variants. Moderate tubular atrophy was found in 11 (11.2%) patients, while mild tubular atrophy was present in 41.8% of cases. Fibro-intimal thickening was noted in less than 10% of cases (Table 1).

A total of 82.6% (81/98) of patients received steroid treatment with a mean duration of 19.9 weeks ± 14.4 weeks. The mean total steroid dose was 4.4 g ± 1.5 g. Due to reasons such as uncontrolled diabetes, intolerance to steroids, risk of osteoporosis, and other complications of immunosuppressive drugs, the remaining patients were treated with ACE inhibitors or ARBs only. Out of the 81 patients who received steroids, 20 (24.6%) patients achieved CR. PR was observed in 9 (11.1%) patients, while, 52 (64.1%) patients showed no response to treatment, highlighting the challenges in effec

| Parameters | Results |

| Follow-up duration in weeks | 136.8 ± 20.6 |

| Total steroid dose in mg | 4391.5 ± 1502.4 |

| Duration of steroid treatment in weeks | 19.9 ± 14.4 |

| Time to remission in weeks | 11.3 ± 6.7 |

| Complete remission | 20/81 (24.6) |

| Partial remission | 9/81 (11.1) |

| No remission | 52/81 (64.1) |

| Spontaneous remission | 2 (2.4) |

| Parameters | Steroid-responsive group, n = 29 | Steroid non-responsive group, n = 52 | P value |

| Age in years | 32.9 ± 13.3 | 38.2 ± 15.2 | 0.123 |

| Sex as male:female | 3.8:1 | 2.1:1 | 0.251 |

| Systolic BP in mmHg | 132.1 ± 22.2 | 131.8 ± 18.6 | 0.946 |

| Diastolic BP in mmHg | 84.9 ± 13.2 | 87.5 ± 12.7 | 0.380 |

| Initial protein in mg/24 hours | 5161.9 ± 3615.2 | 5803.1 ± 3879.4 | 0.569 |

| Serum albumin in g/dL | 1.87 ± 1.06 | 2.05 ± 1.01 | 0.492 |

| Serum creatinine in mg/dL | 2.105 ± 1.81 | 2.20 ± 0.92 | 0.748 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate on presentation in mL/minute/1.73 m2 | 43.2 ± 11.8 | 35.5 ± 11.2 | 0.006 |

| Cumulative steroid dose in mg/kg | 34.5 ± 32.1 | 48.4 ± 37.8 | 0.097 |

| Duration of steroid use in weeks | 22.8 ± 21.7 | 18.3 ± 7.9 | 0.180 |

| Histopathological findings | |||

| Number of glomeruli | 17.25 ± 6.78 | 16.67 ± 9.32 | 0.806 |

| Number of glomeruli with global sclerosis | 2.55 ± 1.64 | 3.63 ± 3.89 | 0.396 |

| Number of glomeruli with segmental sclerosis | 2.53 ± 1.64 | 4.37 ± 3.56 | 0.057 |

| Tubular atrophy | |||

| Mild | 5 (100) | 4 (66.7) | 0.455 |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Fibrointimal thickening of arteries | |||

| Mild | 22 (91.7) | 17 (68) | 0.074 |

| Moderate | 2 (8.3) | 8 (32) | |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis variants | |||

| Not otherwise specified | 15 (51.7) | 24 (46.2) | 0.012 |

| Tip | 11 (37.9) | 7 (13.5) | |

| Collapsing | 2 (6.9) | 15 (28.8) | |

| Hilar | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Cellular | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Unknown/unclassified | 0 (0) | 5 (9.6) |

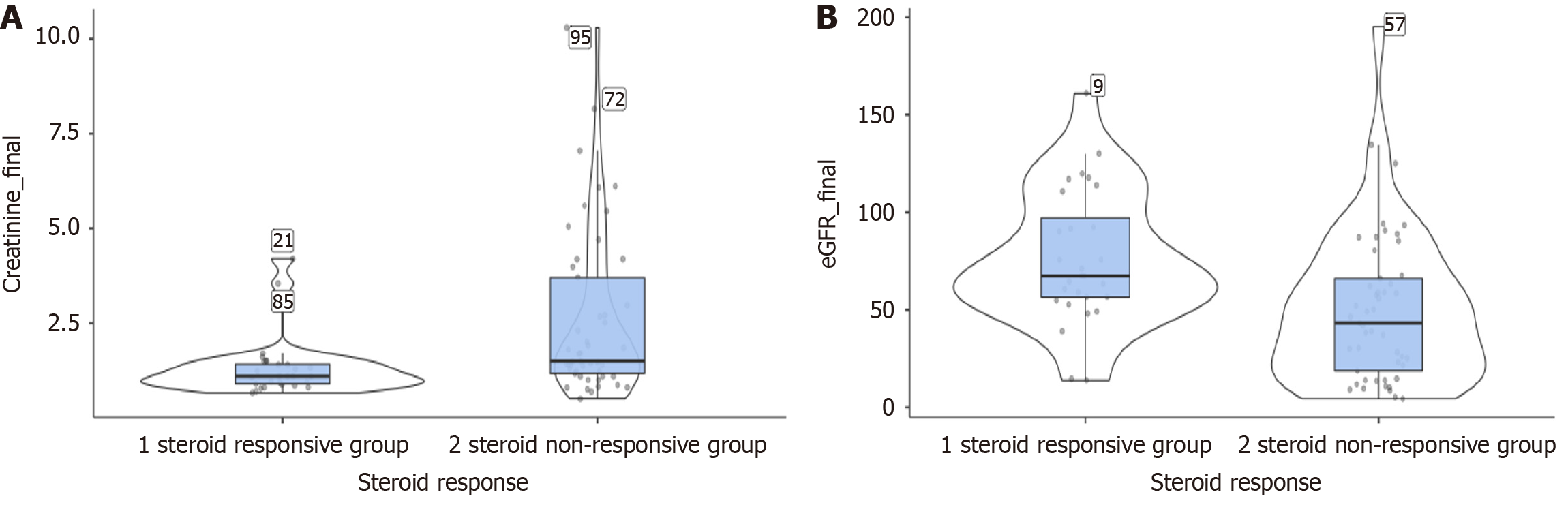

Doubling of serum creatinine was seen in 13/52 (25.0%) steroid non-responsive patients. A total of seven patients developed KFRT, while 15 patients developed CKD. We did not observe any mortality among this cohort of patients.

Table 4 compares the main clinicopathological parameters and outcomes between two groups of adult FSGS patients treated with steroids: (1) Those with kidney function loss (n = 81); and (2) Those with normal kidney function (n = 254) at presentation. Table 4 highlights significant differences between patients with kidney function loss and those with normal kidney function who were treated with steroids. Patients with kidney function loss were older and had higher initial proteinuria, higher serum creatinine levels, more glomeruli with global sclerosis, and a higher rate of moderate tubular atrophy. They also had worse outcomes in terms of the doubling of serum creatinine compared to those with normal kidney function. Other parameters, such as sex, BP, serum albumin, steroid dose, treatment duration, time to remission, and glomeruli with segmental sclerosis, did not show statistically significant differences.

| Parameters | Kidney function loss, n = 81 | Normal kidney function, n = 254 | P value |

| Age in years | 36.3 ± 14.7 | 26.5 ± 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| Sex as male:female | 2.5:1 | 1.9:1 | 0.328 |

| Systolic in mmHg | 131.9 ± 19.8 | 128.4 ± 17.9 | 1.464 |

| Diastolic in mmHg | 86.5 ± 12.8 | 83.9 ± 12.2 | 1.664 |

| Serum albumin in g/dL | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 0.807 |

| Initial proteinuria in mg/24 hours | 5626.2 ± 3787 | 4396.0 ± 2805.2 | 0.009 |

| Serum creatinine in mg/dL | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up duration in weeks | 136.8 ± 120.6 | 152.94 ± 115.6 | 0.243 |

| Total steroid dose in mg | 4391.5 ± 1502.3 | 4279.6 ± 2039.5 | 0.649 |

| Duration of steroid treatment in weeks | 19.90 ± 14.4 | 23.27 ± 23.9 | 0.231 |

| Time to remission | 11.3 ± 6.7 | 12.6 ± 20.4 | 0.705 |

| Number of glomeruli with global sclerosis | 3.6 ± 2.9 | 2.0 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| Number of glomeruli with segmental sclerosis | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 2.9 ± 2.6 | 0.61 |

| Tubular atrophy | |||

| Mild | 39 (79.6) | 133 (90.5) | 0.044 |

| Moderate | 10 (20.4) | 14 (9.5) | |

| Outcomes | |||

| Complete remission | 20/81 (24.7) | 66/254 (25.9) | 0.428 |

| Partial remission | 9/81 (11.1) | 42/254 (16.5) | |

| No remission | 52/81 (64.2) | 146/254 (57.4) | |

| Doubling of serum creatinine | 13/52 (25.0) | 16/146 (10.9) | 0.007 |

Here, we present our experience in one of the largest case series of primary FSGS, focusing on the clinical course and outcomes of adult patients with FSGS who had a loss of kidney function and an eGFR < 60 mL/minute/1.73 m² upon presentation. The SIUT provides free healthcare services to a significant portion of the Pakistani population, which ensures high compliance and regular follow-up. The racial homogeneity of our study population allows for an accurate estimation of the clinical course and outcomes of the FSGS cohort with kidney function loss at presentation.

Kidney function loss was found in 24.4% (98 patients) of FSGS cases upon arrival, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.5:1. These findings are consistent with previous studies. Hemodynamic alterations in acute-onset NS and chronic irreversible changes may contribute to the low eGFR observed at presentation[8,14,15]. Previous reports suggest that steroids can halt FSGS progression or stabilize eGFR, supporting the former mechanism of action in most patients[8].

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of FSGS treatment, and response to steroids is the best predictor of outcomes[16-19]. In this cohort of 81 patients treated with steroids, 29 (35.8%) were steroid-responsive, while 52 (64.1%) were steroid non-responsive. The overall response rate, including CR and PR, was 35.8%. Response rates to steroids in prior studies have varied from 30% to 67%, depending on the dose and duration of steroid treatment[8,16-19]. These findings highlight the need for more robust and targeted therapeutic strategies to improve the treatment outcomes for patients with primary FSGS.

A lower baseline protein excretion was associated with a favorable response to steroids, although it did not reach statistical significance. Prior studies have noted that patients with heavy proteinuria have more severe disease[20-22]. Conversely, lower protein excretion has not consistently been shown to predict a response to steroids.

Surprisingly, the steroid-responsive group had a higher eGFR at presentation compared to the steroid non-responsive group, which was statistically significant. Elevated serum creatinine and decreased eGFR are generally poor prognostic markers in terms of response to steroids and overall kidney survival. In a study enrolling patients with serum creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dL, remission was achieved in only 35.8% of patients, compared to 64.1% in those with lower serum creatinine concentrations[15]. In the steroid-responsive group, there was a statistically significant decrease in serum creatinine and an increase in eGFR, comparable to a prior study conducted at our institute[8].

In patients with FSGS, response to steroids is associated with long-term preservation of renal function[23-25]. Lower levels of serum creatinine showed more complete and partial responses (25.9% and 16.5%) compared to raised levels (24.6% vs 11.1%), with raised creatinine on arrival being associated with KF and the need for kidney replacement therapy on follow-up.

The study has certain limitations related to its retrospective nature, medium-term follow-up duration of 34 months, and being a single-center experience. All eligible patients were treated only with steroids.

In conclusion, primary FSGS patients with low eGFR at presentation have better outcomes if they are steroid-responsive. However, the presence of declining kidney function at presentation is an adverse prognostic indicator, with most patients showing no response to treatment and progressing to overt KF.

| 1. | Shabaka A, Tato Ribera A, Fernández-Juárez G. Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis: State-of-the-Art and Clinical Perspective. Nephron. 2020;144:413-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McDonnell T, Storrar J, Chinnadurai R, Heal C, Chrysochou C, Ritchie J, Rainone F, Poulikakos D, Kalra P, Sinha S. The epidemiology of primary FSGS including cluster analysis over a 20-year period. BMC Nephrol. 2023;24:365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Greenwood AM, Gunnarsson R, Neuen BL, Oliver K, Green SJ, Baer RA. Clinical presentation, treatment and outcome of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in Far North Queensland Australian adults. Nephrology (Carlton). 2017;22:520-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gipson DS, Troost JP, Spino C, Attalla S, Tarnoff J, Massengill S, Lafayette R, Vega-Warner V, Adler S, Gipson P, Elliott M, Kaskel F, Fermin D, Moxey-Mims M, Fine RN, Brown EJ, Reidy K, Tuttle K, Gibson K, Lemley KV, Greenbaum LA, Atkinson MA, Hingorani S, Srivastava T, Sethna CB, Meyers K, Tran C, Dell KM, Wang CS, Yee JL, Sampson MG, Gbadegesin R, Lin JJ, Brady T, Rheault M, Trachtman H. Comparing Kidney Health Outcomes in Children, Adolescents, and Adults With Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2228701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sim JJ, Batech M, Hever A, Harrison TN, Avelar T, Kanter MH, Jacobsen SJ. Distribution of Biopsy-Proven Presumed Primary Glomerulonephropathies in 2000-2011 Among a Racially and Ethnically Diverse US Population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:533-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shiiki H, Nishino T, Uyama H, Kimura T, Nishimoto K, Iwano M, Kanauchi M, Fujii Y, Dohi K. Clinical and morphological predictors of renal outcome in adult patients with focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). Clin Nephrol. 1996;46:362-368. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Alexopoulos E, Stangou M, Papagianni A, Pantzaki A, Papadimitriou M. Factors influencing the course and the response to treatment in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1348-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jafry N, Ahmed E, Mubarak M, Kazi J, Akhter F. Raised serum creatinine at presentation does not adversely affect steroid response in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1101-1106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Beaudreuil S, Lorenzo HK, Elias M, Nnang Obada E, Charpentier B, Durrbach A. Optimal management of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:97-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bagchi S, Agarwal S, Kalaivani M, Bhowmik D, Singh G, Mahajan S, Dinda A. Primary FSGS in Nephrotic Adults: Clinical Profile, Response to Immunosuppression and Outcome. Nephron. 2016;132:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jafry N, Mubarak M, Rauf A, Rasheed F, Ahmed E. Clinical Course and Long-term Outcome of Adults with Primary Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2022;16:195-202. [PubMed] |

| 12. | D'Agati V. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:117-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105:S117-S314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1064] [Article Influence: 1064.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chitalia VC, Wells JE, Robson RA, Searle M, Lynn KL. Predicting renal survival in primary focal glomerulosclerosis from the time of presentation. Kidney Int. 1999;56:2236-2242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cameron JS. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18 Suppl 6:vi45-vi51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Korbet SM. Treatment of primary FSGS in adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1769-1776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ren H, Shen P, Li X, Pan X, Zhang Q, Feng X, Zhang W, Chen N. Treatment and prognosis of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Contrib Nephrol. 2013;181:109-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tang X, Xu F, Chen DM, Zeng CH, Liu ZH. The clinical course and long-term outcome of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in Chinese adults. Clin Nephrol. 2013;80:130-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stirling CM. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis--does treatment work? Nephron Clin Pract. 2006;104:c83-c84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stirling CM, Mathieson P, Boulton-Jones JM, Feehally J, Jayne D, Murray HM, Adu D. Treatment and outcome of adult patients with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in five UK renal units. QJM. 2005;98:443-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shiiki H, Dohi K. Primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: clinical course, predictors of renal outcome and treatment. Intern Med. 2000;39:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ossareh S, Yahyaei M, Asgari M, Bagherzadegan H, Afghahi H. Kidney Outcome in Primary Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) by Using a Predictive Model. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2021;15:408-418. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Tuttle KR, Abner CW, Walker PD, Wang K, Rava A, Heo J, Bunke M. Clinical Characteristics and Histopathology in Adults With Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Med. 2024;6:100748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Trachtman H, Diva U, Murphy E, Wang K, Inrig J, Komers R. Implications of Complete Proteinuria Remission at any Time in Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis: Sparsentan DUET Trial. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:2017-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Troost JP, Trachtman H, Nachman PH, Kretzler M, Spino C, Komers R, Tuller S, Perumal K, Massengill SF, Kamil ES, Oh G, Selewski DT, Gipson P, Gipson DS. An Outcomes-Based Definition of Proteinuria Remission in Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:414-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |