Peer-review started: June 30, 2020

First decision: July 24, 2020

Revised: August 2, 2020

Accepted: August 31, 2020

Article in press: August 31, 2020

Published online: September 25, 2020

Processing time: 86 Days and 20.8 Hours

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) happened in early December and it has affected China in more ways than one. The societal response to the pandemic restricted medical students to their homes. Although students cannot learn about COVID-19 through clinical practice, they can still pay attention to news of COVID-19 through various channels. Although, as suggested by previous studies, some medical students have already volunteered to serve during the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall willingness of Chinese medical students to volunteer for such has not been systematically examined.

To study Chinese medical students’ interest in the relevant knowledge on COVID-19 and what roles they want to play in the pandemic.

Medical students at Peking Union Medical College were surveyed via a web-based questionnaire to obtain data on the extent of interest in the relevant knowledge on COVID-19, attitude towards volunteerism in the pandemic, and career preference. Logistic regression modeling was used to investigate possible factors that could encourage volunteerism among this group in a pandemic.

A total of 552 medical students responded. Most medical students showed a huge interest in COVID-19. The extent of students’ interest in COVID-19 varied among different student-classes (P < 0.05). Senior students had higher scores than the other two classes. The number of people who were ‘glad to volunteer’ in COVID-19 represented 85.6% of the respondents. What these students expressed willingness to undertake involved direct, indirect, and administrative job activities. Logistic regression analysis identified two factors that negatively influenced volunteering in the pandemic: Student-class and hazards of the voluntary job. Factors that positively influenced volunteering were time to watch COVID-19 news, predictable impact on China, and moral responsibility.

More innovative methods can be explored to increase Chinese medical students’ interest in reading about the relevant knowledge on COVID-19 and doing voluntary jobs during the pandemic.

Core Tip: Our survey of Chinese medical students showed an overall strong initiative for volunteerism in the coronavirus disease 2019 (known as COVID-19) pandemic. These students were willing to play direct, indirect, or administrative roles. Student-class and hazards of the voluntary job were the negative influencing factors of volunteering in the pandemic; thus, reducing students’ fear of being infected, such as by providing strong personal protection, can improve their willingness to volunteer. As for their future career preference, nearly half of the students expressed reluctance to engage in pandemic-related specialties, which could imply measures needed to attract potential practitioners in the future.

- Citation: Yu NZ, Li ZJ, Chong YM, Xu Y, Fan JP, Yang Y, Teng Y, Zhang YW, Zhang WC, Zhang MZ, Huang JZ, Wang XJ, Zhang SY, Long X. Chinese medical students’ interest in COVID-19 pandemic. World J Virol 2020; 9(3): 38-46

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v9/i3/38.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v9.i3.38

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), broke out in Hubei Province, China in December 2019[1]. The World Health Organization later declared this outbreak a pandemic, due to its rapid spread across the world[2]. Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province, was locked down on January 23, 2020. As of March 8, 2020 — according to data published by the National Health Commission of China — about 42000 medical staff had been dispatched to different regions of Hubei during the lock-down[3]. Among these was a multidisciplinary team of 186 doctors and nurses from Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) hospital, who managed an intensive care unit (referred to as ICU) from February 4 to April 12 in the Sino-French New City Branch of Tongji Hospital (Wuhan), a designated hospital for COVID-19. No medical student was included in this medical team.

Because the outbreak of COVID-19 coincided with the Chinese Spring Festival, most of the medical students in China were scattered across the country and consequently self-quarantined in their hometowns. The global outbreak has affected medical students worldwide, in many different ways. In the Chinese medical education system, medical students learn basic sciences and clinical medical courses in their junior and middle class-years, respectively; each class has very limited access to clinical practice during this time. Senior class students, on the other hand, enter hospitals for clerkship, internship, or clinical rotation as residents. With the help of various Internet-based learning technologies, the coursework of junior and middle class-year medical students was hardly affected by the pandemic lock-down. However, the clinical practice of senior students had to be suspended.

This disruption in medical school training was not exclusive to China. Medical students at Oxford University Hospitals faced a similar situation[4]. While their medical training was nearly completely suspended, medical students embarked on laboratory jobs and administrative tasks to alleviate the general understaffing burden brought on by the pandemic. Some scholars have advocated such involvement of medical students in the pandemic[5,6]. Yet, there is little data to show medical students’ willingness, particularly for those in China. Thus, we designed and carried out a survey to assess Chinese medical students’ willingness to know more about COVID-19 and participate in the pandemic, and investigate whether COVID-19 had increased their interest in specialties related to the prevention and treatment of severe infectious diseases.

An 18-item questionnaire was designed to evaluate Chinese medical students’ involvement in reading the relevant knowledge of COVID-19, their willingness to volunteer in the pandemic, and whether the outbreak of COVID-19 had any impact on their career choice. The design was adapted from a questionnaire verified by Mortelmans et al[7], inspired by surveys of the influenza pandemic[8] and Middle East respiratory syndrome[9,10], and based on a psychological survey conducted in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak[11]. The majority of items — including willingness to learn about COVID-19, interest level in the relevant knowledge on COVID-19, perceived personal and nationwide impact of COVID-19, and preference of professional choices - were evaluated using a Likert 5-point scale, with 1 being strongly disagree/unwilling and 5 being strongly agree/willing. For other items, the 5-point qualitative scale was as follows: 1-2: “a little”; 3: “moderate”; and 4-5: “very much”. Further, interviewees answered “Yes” or “No” to the question “Are you willing to be a volunteer in the COVID-19 pandemic?”, and selected their access to pandemic information and the type of pandemic-relevant department that they were willing to join. Before distribution, the questionnaire was assessed by an internal consistency test, and the Cronbach-α coefficient was determined to be 0.802. All information was anonymous and informed consent was obtained from respondents. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of PUMC Hospital.

A total of 916 medical students at PUMC, distributed among eight student classes, were invited to fill out the web-based questionnaire. Respondents could submit only a single time and had to answer each question under the platform system settings. From April 10 to April 18, the invitation to fill out the questionnaire was delivered three times, to make sure that every student received the message and with the ultimate goal of maximizing the response rate. By that time, the pandemic crisis-level had been downgraded in China and the lock-down of Wuhan had been lifted (on April 8); the new semester had not yet started at PUMC and the students had been restricted to their homes for more than 2 mo.

All analyses were carried out with the SPSS statistical software package (v23; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Qualitative data are described as constituent ratios. Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for difference analysis between student-class and interest in the relevant knowledge on COVID-19. Logistic regression modeling was used for influencing-factor analysis of willingness to be a volunteer in the COVID-19 pandemic. A P value less than 0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance.

A total of 552 questionnaires (response rate of 60.3%) were returned from 33 provincial administrative regions of China during the 8-d survey period (Figure 1). Among all the responders, 57.8% were female and 42.2% were male. The total respondent pool was divided into three groups according to their curriculum setups, as follows: Junior students, whose coursework involved basic sciences and little medical knowledge; middle-grade students, who received medical education but had no access to clinical practice; and senior students who were currently in clinical rotations. The respondent distribution and the response rate of each group are provided in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Junior | Middle | Senior | Total |

| Study sample, n | 268 | 173 | 475 | 916 |

| Returned questionnaire, n | 157 | 134 | 261 | 552 |

| Response rate | 58.6% | 77.5% | 54.9% | 60.3% |

Seventy-one percent of the respondents showed willingness to follow the progress of the COVID-19 pandemic and sixty-eight percent of them reported that they spent 15-60 min per day on it. The most popular way to access the relevant information was social media (90.9%), followed by news app (67.4%) and television (52.0%). The question “Which aspect of the relevant knowledge on COVID-19 do you know best?” is designated to determine students’ involvement in reading about COVID-19 upon they were self-quarantined at home and to assess which aspect of COVID-19 they will be most interested in when they followed news. Table 2 shows that medical students were most interested in preventive measures in daily life (4.38 ± 0.65) but less interested in diagnostic criteria and treatment procedures (3.12 ± 0.95). The medical students’ preference varied among the different classes. The senior students showed a greater interest in clinical knowledge, such as in-hospital prevention and diagnosis and treatment procedures of COVID-19, followed by middle-grade students (P < 0.05), while the junior students appeared to have the least interest to these aspects. There was no statistically significant difference between the different classes for interest in pathogenesis. As for prevention in daily life, there was a tendency for the seniors to be more into protecting themselves in daily routine than the junior students (P = 0.05) (Table 2).

| Item | Junior | Middle | Senior | Total | P value | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Pathogenesis | 3.45 | 0.87 | 3.53 | 0.91 | 3.62 | 0.85 | 3.55 | 0.87 | 0.098 |

| Prevention in life | 4.29 | 0.68 | 4.37 | 0.61 | 4.44 | 0.65 | 4.38 | 0.65 | 0.05 |

| In-hospital prevention | 3.23 | 1.08 | 3.43 | 0.92 | 3.84 | 0.87 | 3.57 | 0.98 | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis and treatment | 2.85 | 0.97 | 2.99 | 0.95 | 3.34 | 0.87 | 3.12 | 0.95 | < 0.001 |

The number of people who were willing to offer spontaneous support and help in COVID-19 accounted for 85.6% of the respondents. The questionnaire was set up with some items about the role that medical students would prefer to play as a volunteer in the pandemic. Students could arbitrarily choose the task that they wanted to undertake, without being restricted to choose only one item. One-half (50.2%) expressed willingness to provide direct medical services, mainly involving management of patients under the guidance of superior physicians; importantly, this service has a possibility of direct clinical exposure. Indirect medical activities were more popular (69.4%), including working on the clinical front-line but not directly treating the patient. The majority of students (80.4%) expressed willingness to assist in administrative work, such as managing paper files and designing community pamphlets; this work carries the lowest risk of infection.

The incentives cited by the respondent Chinese medical students to volunteer in a pandemic are summarized in Table 3. Binary logistic regression modeling was used to investigate possible factors that could affect medical students’ willingness to volunteer. Female medical students were found to be more likely to volunteer than their male counterparts. Notably, willingness to volunteer decreased with seniority. Next, it was remarkable that students were more willing to be a volunteer with increasingly more time spent on watching news and stronger will to learn about COVID-19. Not surprisingly, students who held the opinion that COVID-19 exerted a huge impact on China and those who thought that doctors volunteer because of moral obligation were more inclined to volunteer. Sixty-three percent of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that health care professionals have a moral obligation to voluntarily provide medical services in a pandemic such as COVID-19. These medical students were significantly more willing to volunteer as well.

| Item | n (%) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Sex | Male | 233 (42.2) | 1 |

| Female | 319 (57.8) | 1.52 (0.86-2.72) | |

| Student class | Junior | 157 (28.4) | 1 |

| Middle | 134 (24.3) | 0.79 (0.36-1.73) | |

| Senior | 261 (47.3) | 0.59 (0.29-1.21) | |

| Time to watch news | < 15 min | 125 (22.6) | 1 |

| 15-30 min | 265 (48.0) | 1.4 (0.7-2.81) | |

| 30-60 min | 111 (20.1) | 2.13 (0.86-5.26) | |

| > 60 min | 51 (9.2) | 2.13 (0.65-6.95) | |

| Willingness to know | Little | 160 (29.0) | 1 |

| Moderate | 242 (43.8) | 1.65 (0.86-3.18) | |

| Very much | 150 (27.2) | 0.85 (0.38-1.88) | |

| Impact on personal life | Little | 85 (15.4) | 1 |

| Moderate | 155 (28.1) | 0.49 (0.16-1.57) | |

| Very much | 312 (56.5) | 0.62 (0.18-2.08) | |

| Impact on China | Little | 97 (17.6) | 1 |

| Moderate | 163 (29.5) | 1.55 (0.6-4.05) | |

| Very much | 292 (52.9) | 2.16 (0.81-5.76) | |

| Doctors' obligation | Little | 202 (36.6) | 1 |

| Moderate | 216 (39.1) | 4.29 (2.25-8.16) | |

| Very much | 134 (24.3) | 28.22 (6.03-131.98) | |

| Hazards of voluntary job | Little | 236 (42.8) | 1 |

| Moderate | 256 (46.4) | 0.43 (0.22-0.85) | |

| Very much | 60 (10.9) | 0.24 (0.1-0.58) | |

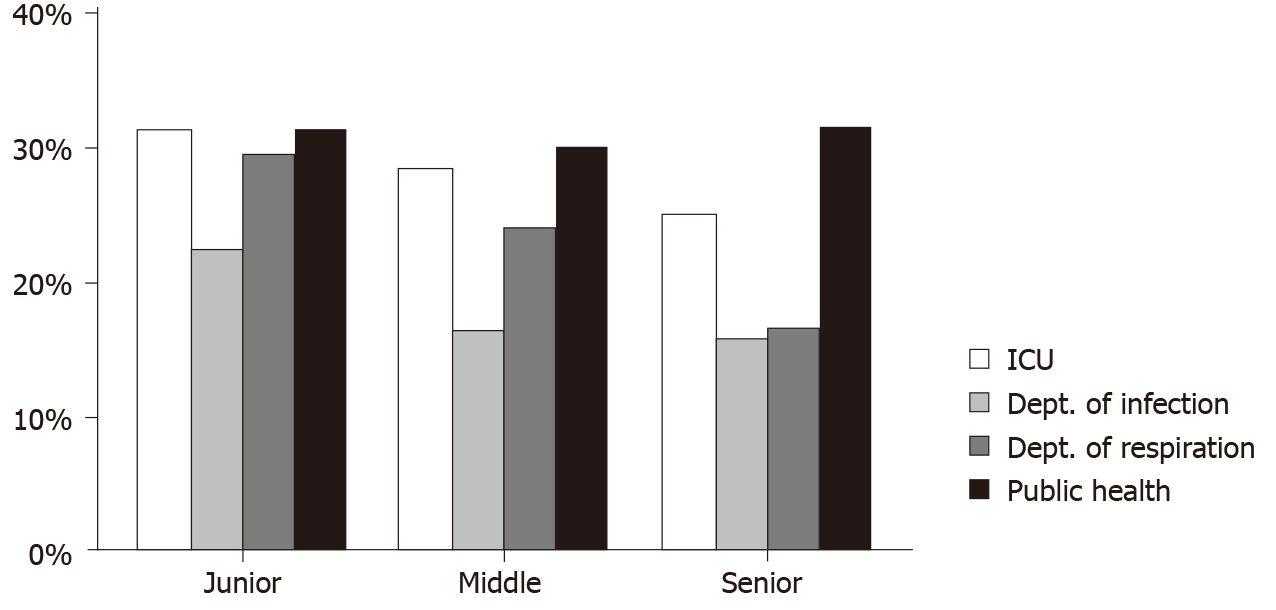

How the pandemic was affecting career preference of medical students is illustrated in Figure 2. When asked to rate their inclination to join pandemic-related specialties (more than one option was available), nearly half of the students expressed reluctance. Public health specialties were the most popular among all related specialties, followed by ICU. Among the students who were interested in COVID-19-related specialties, only 18% chose infectious disease, making it the least popular option.

It has been debated whether medical students should serve in a pandemic such as COVID-19, owing to the possibility of their getting infected during the clinical practice activities and their lack in knowledge about severe infectious disease[6,11]. So far, the different countries affected by COVID-19 have reacted differently. Portugal declared the closure of medical schools after 31 cases were confirmed[12]. On March 17, 2020, the American College of Medicine Association (United States) recommended suspension of all direct patient contact responsibilities for medical students[13] but policies differed among districts. New York University offered voluntary opportunities for senior students who met all graduation requirements to graduate in advance of the pandemic, and planned to have them in internal medicine and emergency departments[14].

At the same time, some medical students were also enthusiastic to offer their help during the pandemic. Compared with clinical jobs, non-clinical jobs seemed to be more acceptable. Medical students at Columbia University (New York, NY, United States) initiated a virtual volunteer group to perform the necessary chores for hospital staff and to participate in a COVID-19 laboratory program[15]. More than 500 medical students at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA, United States) spontaneously formed volunteer teams to fulfill their potential through community mobilization[16]. To our relief, the study conducted at PUMC showed that Chinese medical students were also likely to offer support and help in a pandemic. This trend was more obvious when students sensed the threat of COVID-19 to China.

The self-assessment of results from PUMC, presented herein, indicate that students showed preference to know COVID-19 daily life prevention than hospital settings. Not surprisingly, the senior medical students had higher scores than their junior class counterparts for interest in disease prevention. This suggests that younger volunteers, who still lacked sufficient working experience in hospital, have not been aware of the significance of disease prevention yet, thus indicating that more consciousness and knowledge about self-protection can be instilled into these younger students.

According to our survey, several factors influenced the Chinese medical student’s willingness to serve in a pandemic. It seems that senior students are more reluctant to volunteer. This may be because most of the senior students have their specialty of choice already. Moreover, the possibility of getting infected may have deterred them. Other influencing factors have been seen in previous studies, in which several lines of evidence have been obtained to suggest that inefficiency, prior training, financial security, and access to protective equipment can affect medical students' enthusiasm to be volunteers[17]. Ultimately, focusing on these collective factors will not only improve medical students’ volunteerism but their protection as well.

This study also indicated that medical students preferred to get information from social media and news apps. According to data published by the China Internet Network Information Center at the end of March of this year, 265 million students turned to online education. The number of online education users in China reached 423 million, equating to an increase of 110.2% from the end of 2018[18]. After the pandemic, schools can still consider a combination of in-class learning and some online learning modalities[19]. Our findings also confirmed the popularity and feasibility of this way. It can be a good chance for schools to penetrate into students' social circles and raise their intention of being volunteers by means of, for instance, posting high-quality videos about COVID-19 on social media[20].

The outbreak of COVID-19 also exposes the potential understaffing. It is imperative to take measures to appeal more practitioners. Although preventive medical courses are provided to students, there is no curriculum about public principles in response to emerging infectious diseases, and gradually students are reluctant to become doctors related to epidemic control[21]. It is reassuring that even not in clinical practice, medical students take a vivid public health course through COVID-19, which may increase students' emphasis on epidemic-related specialties. Although it remains unclear to know what extent their plans to specialize in a specialty relevant to the pandemic was altered by the pandemic, nearly 80% of students believed that this outbreak improved their interest and understanding of public health, which can be a good sign. Thus far, previous studies have revealed a correlation between lack of incentive mechanisms, little perception of public health, and students' choice of community medicine[22]. This suggests that students should be made clear of the significance of epidemic-relevant specialties, and encouraged by role models who have worked in epidemic areas.

This study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting our findings. First, for the purpose of a higher response rate, only students at PUMC were surveyed; thus, the data collected might not be representative of the entire student population in China. However, despite studying at the same college (PUMC), the students involved in our study originated from across the entire country. Undoubtedly, our findings should be further confirmed by a multi-center study. A web-based questionnaire also has particular benefits for our study population, as it complements the geographic restriction caused by the pandemic. Second, the questionnaire was delivered in early April, when the pandemic in China had been basically controlled, and students were inherently more familiar with COVID-19. Hence, the results might be less optimistic if it had been conducted at an earlier stage of the pandemic.

In this study, a web-based questionnaire was used to reveal Chinese medical students’ interest in the international public health event, COVID-19. We found that this emerging pandemic triggered students' curiosity and prompted their interest in reading about and responding to related events. Overall, students tended to read more about daily life prevention of COVID-19, and they expressed their passion to participate in volunteer activities in different ways.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has raged across the world. The dramatically increasing numbers of infected cases consequently caused a heavy burden on medical staff worldwide. With the intent of helping ease the burden of medical systems, some medical students have been willing to volunteer in the pandemic but there is little systematic evidence to show that among Chinese medical students.

As medical students will emerge as the practitioners during future outbreaks and pandemics, it is essential to determine the profile of incentivizing factors for such volunteer work today. This knowledge will also help to construct strategies that will improve their enthusiasm for volunteerism.

A total of 552 medical students at Peking Union Medical College responded to the study questionnaire.

This study was online-based and conducted through a questionnaire that explored students’ interest in the relevant knowledge on COVID-19, attitude towards volunteerism in the pandemic, and career preference. Logistic regression modeling was used to investigate possible factors that could encourage medical students to volunteer in a pandemic.

Chinese medical students expressed a strong initiative to aid in COVID-19 by means of taking on direct, indirect, or administrative responsibilities. There were two negative influencing factors, namely, student-class and hazards associated with the voluntary job, which suggested that reducing students’ fear of being infected and offering sufficient personal protection could help improve volunteerism in a pandemic. In terms of future career preference, nearly half of the students expressed reluctance to engage in pandemic-related specialties, which could imply more measures to attract potential practitioners in the future.

Most Chinese medical students take initiatives to learn about COVID-19 and are glad to volunteer in a pandemic. However, hazards associated with the voluntary job can likely damp down students’ enthusiasm for volunteerism, which means more innovative methods, such as Internet platforms, sufficient personal protection, specialized knowledge, and full training in advance, can be explored.

Multi-center studies are needed, taking racial, geographic distribution, educational background, parental background, income and academic performance, etc. into consideration. In addition, more standard assessment questionnaires should be made and enacted to evaluate students’ comprehensive understanding of COVID-19, in order to reduce the bias of different surveys conducted in different regions.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Virology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huff HV S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18987] [Cited by in RCA: 17630] [Article Influence: 3526.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, Cereda D, Coluccello A, Foti G, Fumagalli R, Iotti G, Latronico N, Lorini L, Merler S, Natalini G, Piatti A, Ranieri MV, Scandroglio AM, Storti E, Cecconi M, Pesenti A; COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3537] [Cited by in RCA: 3825] [Article Influence: 765.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Press conference of the joint prevention and control mechanism of the state council [Press release]. Beijing: Propaganda department, April 7, 2020. |

| 4. | Armstrong A, Jeevaratnam J, Murphy G, Pasha M, Tough A, Conway-Jones R, Mifsud RW, Tucker S. A plastic surgery service response to COVID-19 in one of the largest teaching hospitals in Europe. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73:1174-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thomson E, Lovegrove S. 'Let us Help'-Why senior medical students are the next step in battling the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;e13516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Miller DG, Pierson L, Doernberg S. The Role of Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:145-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mortelmans LJ, De Cauwer HG, Van Dyck E, Monballyu P, Van Giel R, Van Turnhout E. Are Belgian senior medical students ready to deliver basic medical care in case of a H5N1 pandemic? Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24:438-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rosychuk RJ, Bailey T, Haines C, Lake R, Herman B, Yonge O, Marrie TJ. Willingness to volunteer during an influenza pandemic: perspectives from students and staff at a large Canadian university. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2008;2:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Al-Mohrej A, Agha S. Are Saudi medical students aware of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus during an outbreak? J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:388-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu M, Jiang C, Donovan C, Wen Y, Sun W. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome and Medical Students: Letter from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:13289-13294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4551] [Cited by in RCA: 5133] [Article Influence: 1026.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Mahase E. Covid-19: Portugal closes all medical schools after 31 cases confirmed in the country. BMJ. 2020;368:m986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 844] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 172.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | DeWitt DE. Fighting COVID-19: Enabling Graduating Students to Start Internship Early at Their Own Medical School. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:143-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Iserson KV. Augmenting the Disaster Healthcare Workforce. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:490-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Soled D, Goel S, Barry D, Erfani P, Joseph N, Kochis M, Uppal N, Velasquez D, Vora K, Scott KW. Medical Student Mobilization During A Crisis: Lessons From A COVID-19 Medical Student Response Team. Acad Med. 2020;95:1384-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gouda P, Kirk A, Sweeney AM, O'Donovan D. Attitudes of Medical Students Toward Volunteering in Emergency Situations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | CINI Center. The 45th China statistical report on internet development. 2020. |

| 19. | Eltayar AN, Eldesoky NI, Khalifa H, Rashed S. Online faculty development using cognitive apprenticeship in response to COVID-19. Med Educ. 2020;54:665-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bauchner H, Sharfstein J. A Bold Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Medical Students, National Service, and Public Health. JAMA. 2020;Online ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schröder-Bäck P, Duncan P, Sherlaw W, Brall C, Czabanowska K. Teaching seven principles for public health ethics: towards a curriculum for a short course on ethics in public health programmes. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang L, Bossert T, Mahal A, Hu G, Guo Q, Liu Y. Attitudes towards primary care career in community health centers among medical students in China. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |