Published online Mar 25, 2025. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v14.i1.96098

Revised: October 16, 2024

Accepted: November 13, 2024

Published online: March 25, 2025

Processing time: 215 Days and 9.4 Hours

Transfusion transmissible infections (TTIs) are illnesses spread through contaminated blood or blood products. In India, screening for TTIs such as hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-I/II, malaria, and syphilis is mandatory before blood transfusions. Worldwide, HCV, HBV, and HIV are the leading viruses causing mortality, affecting millions of people globally, including those with co-infections of HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV. Studies highlight the impact of TTIs on life expectancy and health risks, such as liver cirrhosis, cancer, and other diseases in individuals with chronic HBV. Globally, millions of blood donations take place annually, emphasizing the importance of maintaining blood safety.

To study the prevalence of TTIs, viz., HBV, HCV, HIV I/II, syphilis, and malaria parasite (MP), among different blood donor groups.

The study assessed the prevalence of TTIs among different blood donor groups in Delhi, India. Groups included total donors, in-house donors, total camp donors, institutional camp donors, and community camp donors. Tests for HIV, HBV, and HCV were done using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, while syphilis was tested with rapid plasma reagins and MP rapid card methods. The prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV, and syphilis, expressed as percentages. Differences in infection rates between the groups were analyzed using χ² tests and P-values (less than 0.05).

The study evaluated TTIs among 42158 blood donors in Delhi. The overall cumulative frequency of TTIs in total blood donors was 2.071%, and the frequencies of HBV, HCV, HIV-I/II, venereal disease research laboratory, and MP were 1.048%, 0.425%, 0.221%, 0.377%, and 0.0024%, respectively. In-house donors, representing 37656 donors, had the highest transfusion transmissible infection (TTI) prevalence at 2.167%. Among total camp donors (4502 donors), TTIs were identified in 1.266% of donors, while community camp donors (2439 donors) exhibited a prevalence of 1.558%. Institutional camp donors (2063 donors) had the lowest TTI prevalence at 0.921%. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in overall TTI prevalence, with total and in-house donors exhibiting higher rates compared to camp donors.

Ongoing monitoring and effective screening programs are essential for minimizing TTIs. Customizing blood safety measures for different donor groups and studying socio-economic-health factors is essential to improving blood safety.

Core Tip: The study examined transfusion transmissible infection (TTI) among blood donors, assessing differences across groups: (1) In-house donors; (2) Total camp donors; (3) Institutional camp donors; and (4) Community camp donors. Findings revealed higher TTI prevalence in in-house donors (2.17%), followed by total donors (2.07%). Community camp donors and total camp donors had lower TTI rates at 1.56% and 1.27%, respectively, while institutional camp donors had the lowest rate at 0.92%. Statistical comparisons indicated significant differences in TTI prevalence between various groups.

- Citation: Thakur SK, Sinha AK, Sharma SK, Jahan A, Negi DK, Gupta R, Singh S. Prevalence of transfusion transmissible infections among various donor groups: A comparative analysis. World J Virol 2025; 14(1): 96098

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v14/i1/96098.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v14.i1.96098

Transfusion transmissible infections (TTIs) include a range of illnesses that can be transmitted through the use of contaminated blood or blood products. Key TTIs include hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-I/II, and syphilis. In India, screening for TTIs such as HIV-I/II, HBV, HCV, malaria parasite (MP), and syphilis is mandatory before any blood transfusion[1,2].

Globally, the three most prevalent viruses causing mortality are HCV, HBV, and HIV[3]. Epidemiological data indicate that there are approximately 71.0 million individuals living with HCV, 25.70 million with HBV, and 36.70 million with HIV worldwide. Additionally, according to an estimate, 2.30 million and 2.70 million patients suffer from co-infections of HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV, respectively, due to similar transmission routes[4]. A study in Tuscany, Italy, revealed an increase in life expectancy at birth of 2.9 years for men and 2.6 years for women, while an increase in infectious disease mortality resulted in a decrease in life expectancy by 0.11 years for men and 0.16 years for women[5]. Research in Pakistan found that HBV and HCV prevalence rates were 6.7% and 14.3%, respectively, with 80% of co-morbidities consisting of HIV/HCV and 20% consisting of HBV/HCV[6,7]. Chronic HBV infection heightens the risk for liver cirrhosis, cancer, and other diseases, posing a high level of contagion[8]. HCV and HBV infections are also prevalent among individuals living with HIV due to shared transmission pathways. Co-morbidities such as liver complications due to HCV or HBV infection are significant concerns for those infected with HIV[9]. Yearly, about 93 million blood donations take place worldwide. In India, about 30 million blood components are transfused annually[10].

TTIs are a major health concern due to their potential to be transmitted through blood transfusions, which necessitates careful screening and monitoring. Their prevalence varies across different populations, making it crucial to understand the distribution of TTIs in specific regions. On study of English literature, we found an occasional study[11] highlighting the different prevalence of TTIs among various donor groups. Consequently, this study focuses on assessing the prevalence of TTIs among various groups of blood donors in Delhi.

All necessary biosafety measures and infection control protocols were strictly adhered to during the collection and testing of blood samples. Volunteer and replacement blood donors were counseled and evaluated according to standard operating procedures before being permitted to donate blood at the blood bank.

The study selected blood donors who met specific health and safety standards and did not have a risk of transmission of TTIs. Eligible donors had no recent, past, or current history of hepatitis, chronic diseases, sexually transmitted diseases, surgery, asthma, high-risk activities (such as unprotected intercourse), or pregnancy. Participants were required to be in good physical health, aged 18 years to 65 years, weighing over 45 kg, and with hemoglobin levels greater than 12.5 gm/dL[12].

Donors who did not meet the qualifications for blood donation were excluded from this study.

After donation, the donor's blood was tested for TTIs. Commercially available testing kits were used according to the manufacturer's guidelines. The blood samples underwent testing for HIV-I/II, HBV, and HCV using standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test kits. The detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) utilized MonolisaTM HBsAg ULTRA (BIO-RAD, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) with 100% sensitivity and 99.94% specificity. Combined screening for anti-HCV antibodies and HCV antigens in serum/plasma was conducted with MonolisaTM HCV Ag-Ab ULTRA V2 (BIO-RAD, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), which had 100% sensitivity and 99.94% specificity. Screening for the detection of HIV P24 antigen and antibodies to HIV-I and II in human plasma/serum was carried out using GenscreenTM ULTRA HIV Ag-Ab (BIO-RAD, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), with 100% sensitivity and 99.95% specificity. Antibodies for Treponema pallidum were tested using rapid plasma reagins carbon antigen test (RECKON DIAGNOSTICS P. LTD., Gorwa, Vadodara, India). Screening tests for malaria parasite antigens, including Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) and Plasmodium vivax (Pv), were detected by utilizing the Malaria Pf/Pv Ag Rapid Test kit, a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay (BIOGENIX INC. PVT. LTD., Lucknow, India).

This study provides a comparative analysis of the prevalence of TTIs among various groups of blood donors. Groups included in the study are defined as follows: (1) In-house donors encompass all blood donation units, including in-house donors (both voluntary and replacement donors who donated blood at the blood center for the transfusion needs of their relatives or friends); (2) Total camp donors refer to blood units collected from voluntary blood donation camps, encompassing both institutional and community camp donors; (3) Institutional camp donors are voluntary donors who donated blood within institutional settings; (4) Community camp donors consist of voluntary donors who donated blood at community gatherings; and (5) Total donors include total camp donors and all in-house donors.

Data were collected from blood bank inventory registers [blood donation and transfusion transmissible infection (TTI) testing registers] and entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets for analysis. The study examined the prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV, and syphilis, expressed as percentages. Statistical comparisons were made using χ² and P-values to assess the differences in infection rates between these groups. Analyses were performed using the open-source statistical software R version 4.0.0. A P-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In the present study, data from 42158 blood donors (total donors) was included (Table 1). There were 37656 voluntary and replacement blood donors who had donated blood in-house in the blood center for the transfusion needs of their relatives or friends (in-house donors). A total of 4502 units were collected from voluntary blood donation camps that include institutional camp donors and community camp donors (total camp donors). There were 2063 voluntary blood donors who donated blood in institutional settings (institutional camp donors); this group of voluntary blood donors were either employed in the institutions or were students studying in the education institutions. There were 2439 voluntary blood donors who had donated blood at a community gathering (community camp donors).

| Total donors | In-house donors | Total camp donors | Institutional camp donors | Community camp donors | ||

| Donors | 42158 (100) | 37656 (100) | 4502 (100) | 2063 (100) | 2439 (100) | |

| Hepatitis B virus | Reactive | 442 (1.048) | 416 (1.105) | 26 (0.578) | 11 (0.533) | 15 (0.615) |

| Non reactive | 41716 (98.95) | 37240 (98.9) | 4476 (99.42) | 2052 (99.47) | 2424 (99.38) | |

| Hepatitis C virus | Reactive | 179 (0.425) | 168 (0.446) | 11 (0.244) | 4 (0.194) | 7 (0.287) |

| Non reactive | 41979 (99.58) | 37488 (99.55) | 4491 (99.76) | 2059 (99.81) | 2432 (99.71) | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | Reactive | 93 (0.221) | 85 (0.226) | 8 (0.178) | 2 (0.097) | 6 (0.246) |

| Non reactive | 42065 (99.78) | 37571 (99.77) | 4494 (99.82) | 2061 (99.9) | 2433 (99.75) | |

| Syphilis | Reactive | 159 (0.377) | 147 (0.39) | 12 (0.267) | 2 (0.097) | 10 (0.41) |

| Non reactive | 41999 (99.62) | 37509 (99.61) | 4490 (99.73) | 2061 (99.9) | 2429 (99.59) | |

| Transfusion transmissible infection | Reactive | 873 (2.071) | 816 (2.167) | 57 (1.266) | 19 (0.921) | 38 (1.558) |

| Non reactive | 41285 (97.93) | 36840 (97.83) | 4445 (98.73) | 2044 (99.08) | 2401 (98.44) | |

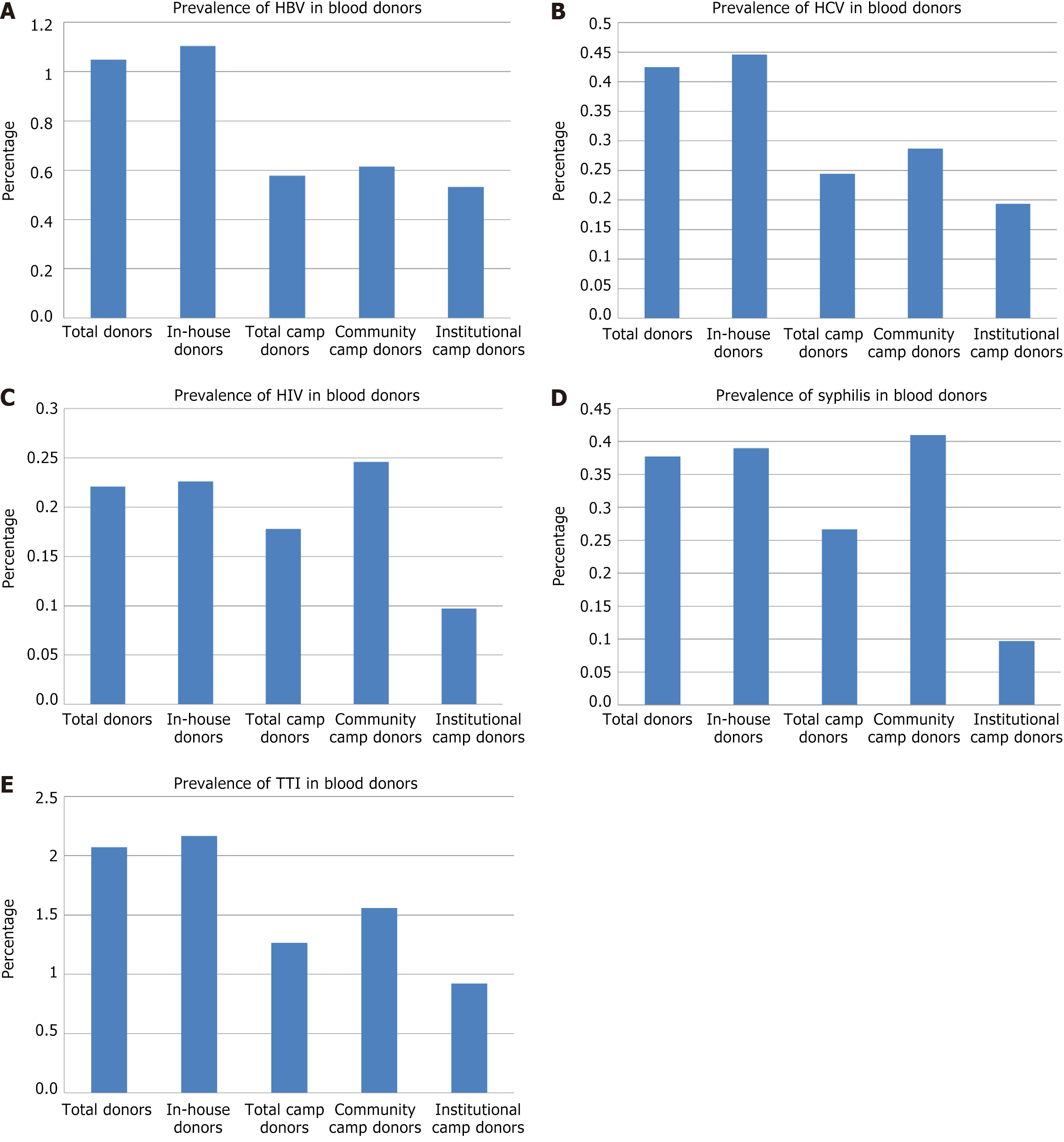

Among the total donors (total donors) the proportion of TTI was as follows (Table 1, Figure 1): One or more TTI was identified in a total of 873 (2.071%) donors. Of these, HBV reactivity was seen in 442 (1.048%), HCV reactivity was seen in 179 (0.425%), HIV reactivity was seen in 93 (0.221%), and syphilis reactivity was seen in 159 (0.377%) donors. Among total blood donors, only one (0.0023%) was positive for MP.

Among the in-house donor (in-house donors) the proportion of TTI was as follows (Table 1, Figure 1): One or more TTI was identified in a total of 816 (2.167%) donors. Of these, HBV reactivity was seen in 416 (1.105%), HCV reactivity was seen in 168 (0.446%), HIV reactivity was seen in 85 (0.226%), and syphilis reactivity was seen in 147 (0.39%) donors.

Among the total blood donation in camp (total camp donors), the proportion of TTI was as follows (Table 1, Figure 1): One or more TTI was identified in a total of 57 (1.266%) donors. Of these, HBV reactivity was seen in 26 (0.578%), HCV reactivity was seen in 11 (0.244%), HIV reactivity was seen in 8 (0.178%), and syphilis reactivity was seen in 12 (0.267%) donors.

Among the blood donation camps organized in institutions (institutional camp donors), the proportion of TTI was as follows (Table 1, Figure 1): One or more TTI was identified in a total of 19 (0.921%) donors. Of these, HBV reactivity was seen in 11 (0.533%), HCV reactivity was seen in 4 (0.194%), HIV reactivity was seen in 2 (0.097%), and syphilis reactivity was seen in 2 (0.097%) donors.

Among the blood donation camps organized in the community (community camp donors), the proportion of TTI was as follows (Table 1, Figure 1): One or more TTI was identified in a total of 38 (1.558%) donors. Of these, HBV reactivity was seen in 15 (0.615%), HCV reactivity was seen in 7 (0.287%), HIV reactivity was seen in 6 (0.246%), and syphilis reactivity was seen in 10 (0.41%) donors.

Overall, the distribution of infections varied across donor groups, with in-house donors showing the highest rates of TTIs and related infections.

Across the various donor groups, the prevalence of TTIs varied, with the highest incidence observed among in-house donors (2.167%), followed by total donors (2.0708%), community camp donors (1.558%), total camp donors (1.2661%), and lowest in institutional camp donors (0.921%). Across all groups (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1), the majority of donations were non-reactive for each infection, with non-reactivity rates ranging from 98.44% to 99.90%. The overall prevalence of TTI was significantly higher in total donors compared to total camp donors (P = 0.0002) and institutional camp donors (P = 0.0003). The overall prevalence of TTI was significantly higher in in-house donors compared to total camp donors (P = 0.0001) and institutional camp donors (P = 0.0001) as well as community camp donors (P = 0.043).

| Hepatitis B virus | Hepatitis C virus | Human immunodeficiency virus | Syphilis | Transfusion transmissible infections | ||||||

| χ² | P value | χ² | P value | χ² | P value | χ² | P value | χ² | P value | |

| Total donors and in-house donors | 0.5929 | 0.4413 | 0.2134 | 0.6441 | 0.0235 | 0.8781 | 0.0911 | 0.7628 | 0.8887 | 0.3458 |

| Total donors and total camp donors | 9.0846 | 0.0026 | 3.259 | 0.071 | 0.3466 | 0.556 | 1.3628 | 0.2431 | 13.483 | 0.0002 |

| Total donors and institutional camp donors | 5.1494 | 0.0233 | 2.54 | 0.111 | 1.4028 | 0.2363 | 4.2569 | 0.0391 | 13.155 | 0.0003 |

| Total donors and community camp donors | 4.2706 | 0.0388 | 1.0509 | 0.3053 | 0.0672 | 0.7955 | 0.0659 | 0.7974 | 3.0295 | 0.0818 |

| In-house donors and total camp donors | 10.774 | 0.001 | 3.8736 | 0.0491 | 0.4214 | 0.5162 | 1.641 | 0.2002 | 16.093 | 0.0001 |

| In-house donors and institutional camp donors | 6.0074 | 0.0142 | 2.8864 | 0.0893 | 1.4841 | 0.2231 | 4.506 | 0.0338 | 14.754 | 0.0001 |

| In-house donors and community camp donors | 5.1663 | 0.023 | 1.335 | 0.2479 | 0.0416 | 0.8384 | 0.0226 | 0.8804 | 4.075 | 0.0435 |

| Total camp donors and institutional camp donors | 0.0496 | 0.8238 | 0.1579 | 0.6911 | 0.6066 | 0.4361 | 1.9123 | 0.1667 | 1.4726 | 0.2249 |

| Total camp donors and community camp donors | 0.0379 | 0.8457 | 0.1113 | 0.7386 | 0.3667 | 0.5448 | 1.0304 | 0.3101 | 0.9986 | 0.3177 |

| Institutional camp donors and community camp donor | 0.1303 | 0.7182 | 0.3975 | 0.5284 | 1.3999 | 0.2367 | 4.1204 | 0.0424 | 3.6281 | 0.0568 |

Across the various donor groups (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1), the prevalence of HBV varied, with the highest incidence observed among in-house donors (1.105%), followed by total donors (1.048%), community camp donors (0.615%), total camp donors (0.578%), and institutional camp donors (0.533%). There was a statistically significant difference in HBV prevalence between total donors and total camp donors (χ² = 9.0846, P = 0.0026), as well as between total donors and institutional camp donors (χ² = 5.1494, P = 0.0233), and between total donors and community camp donors (χ² = 4.2706, P = 0.0388). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in HBV prevalence between total donors and in-house donors.

Across the various donor groups (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1), the prevalence of HCV varied, with the highest incidence observed among in-house donors (0.446%), followed by total donors (0.425%), community camp donors (0.87%), total camp donors (0.244%), and institutional camp donors (0.194%). Regarding HCV, there were significant differences between in-house donors and total camp donors (χ² = 3.8736, P = 0.0491), but comparisons between total donors and other groups did not show significant differences.

Across the various donor groups (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1), the prevalence of HIV varied, with the highest incidence observed among community camp donors (0.246%), followed by in-house donors (0.226%), total donors (0.221%), total camp donors (0.178%), and institutional camp donors (0.097%). The comparisons for HIV prevalence did not reveal statistically significant differences across different donor groups.

Across the various donor groups (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1), the prevalence of syphilis varied, with the highest incidence observed among community camp donors (0.41%), followed by in-house donors (0.39%), total donors (0.377%), total camp donors (0.267%), and institutional camp donors (0.097%). In terms of syphilis, a significant difference was noted between total donors and institutional camp donors (χ² = 4.2569, P = 0.0391), but not between total donors and other groups.

The prevalence of TTIs varies significantly across different regions within India and in other countries worldwide. The current study focused on the prevalence of TTIs among blood donors in Delhi, India, and found values consistent with figures observed in other parts of the country and worldwide (Table 3)[10,12-27].

| No. | States of India | Transfusion transmissible infections | Hepatitis B virus | Hepatitis C virus | Human immunodeficiency virus | Syphilis | Malaria parasite |

| 1 | Present study (Delhi, India) | 2.071 | 1.048 | 0.425 | 0.221 | 0.377 | 0.002 |

| 2 | India, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.58 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.06 |

| Northern zone | |||||||

| 3 | Delhi, 2023, Thakur et al[12] | 2.04 | 1.11 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| 4 | Delhi, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.03 | 1.06 | 0.54 | 0.2 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| 5 | Jammu and Kashmir, 2016, ABBI[13] | 0.86 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| 6 | Himachal Pradesh, 2016, ABBI[13] | 0.69 | 0.38 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| 7 | Punjab, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.64 | 0.65 | 1.35 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0.01 |

| 8 | Chandigarh, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.21 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| 9 | Haryana, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.97 | 0.87 | 0.8 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| 10 | Rajasthan, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.75 | 1.21 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.02 |

| Central zone | |||||||

| 11 | Uttarakhand, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.79 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| 12 | Uttar Pradesh, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.49 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| 13 | Madhya Pradesh, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.24 | 1.14 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.36 | 0.56 |

| 14 | Bhopal, 2023, Shrivastava et al[10] | 2.7 | 1.8 | 0.42 | 0.2 | 0.31 | 0.02 |

| 15 | Chhattisgarh, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.32 | 0.68 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.3 | 0.04 |

| 16 | Central India, 2019, Varma et al[14] | 1.43 | 1.29 | 0.07 | 0.08 | - | - |

| Eastern zone | |||||||

| 17 | Sikkim, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.1 | 0.59 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| 18 | West Bengal, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.05 | 0.9 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.02 |

| 19 | Bihar, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.84 | 1.42 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| 20 | Odisha, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.29 | 0.8 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| 21 | Odisha, 2020, Prakash et al[15] | 1.89 | 0.97 | 0.41 | 0.35 | - | - |

| 22 | Jharkhand, 2016, ABBI[13] | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| 23 | Ranchi, India, 2015, Sunderam et al[16] | 1.01 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.33 | |

| Western zone | |||||||

| 24 | Maharashtra, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.66 | 1.02 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 25 | Gujarat, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.03 | 0.59 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| 26 | Ahmadabad, 2022, Patel et al[17] | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.19 | - |

| 27 | Gujarat, 2016, Bharadva et al[18] | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | - | |

| 28 | Dadra and Nagar Haveli, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.18 | 1.79 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| 29 | Daman and Diu, 2016, ABBI[13] | 0.59 | - | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Southern zone | |||||||

| 30 | Telangana, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.31 | 0.67 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.22 |

| 31 | Telangana, 2016, Fatima et al[19] | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | |

| 32 | Andhra Pradesh, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.91 | 1.39 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| 33 | Karnataka, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.36 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| 34 | Tamil Nadu, 2016, ABBI[13] | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| 35 | Kerala, 2016, ABBI[13] | 0.56 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 36 | Puducherry, 2016, ABBI[13] | 3.13 | 2.12 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| 37 | Andaman and Nicobar, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.76 |

| 38 | Goa, 2016, ABBI[13] | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| North East zone | |||||||

| 39 | Arunachal Pradesh, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.19 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.36 |

| 40 | Meghalaya, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.18 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.73 | 0.04 |

| 41 | Mizoram, 2016, ABBI[13] | 2.48 | 0.94 | 1.24 | 0.3 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 42 | Manipur, 2016, ABBI[13] | 1.62 | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 43 | Tripura[13] | 1.5 | 1.25 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| 44 | Assam[13] | 1.23 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.3 | 0.03 |

| 45 | Nagaland[13] | 1.01 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Country (worldwide) | |||||||

| 46 | Tehran, Iran, 2014, Mohammadali and Pourfathollah et al[20] | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.010 | - | |

| 47 | Peshawar, Pakistan, 2017, Batool et al[21] | 5.33 | 2.30 | 1.30 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 0.76 |

| 48 | Islamabad, Pakistan, 2022, Bhatti et al[22] | 4.41 | 0.01 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.004 |

| 49 | WR Saudi Arabia, 2022, Altayar et al[23] | 7.93 | 3.97 | - | 0.02 | - | 2.21 |

| 50 | NW, Ethiopia, 2022, Legese et al[24] | 5.43 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.5 | - |

| 51 | Eastern Ethiopia, 2018, Ataro et al[25] | 7.06 | 4.67 | 0.96 | 1.24 | 0.44 | - |

| 52 | Brazil, 2019, Pessoni et al[26] | 4.04 | 1.63 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.87 | - |

| 53 | Malawi, Kenya and Ghana, 2023, Singogo et al[27] | 10.7 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.3 | - |

Our study results show, overall cumulative frequency of TTIs in blood donors was 2.071%, and frequency of HBV, HCV, HIV-I/II, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) and MP were 1.048%, 0.425%, 0.221%, 0.377% and 0.0024% respectively. Our study results show the overall cumulative frequency of TTIs in blood donors as 2.071%, and the frequencies of HBV, HIV-I/II, HCV, syphilis, and MP were 0.425%, 1.048%, 0.221%, 0.377%, and 0.0024%, respectively. The overall prevalence of TTIs in the present study was similar to the findings of Thakur et al[12], who have reported an overall TTI prevalence of 2.038% (1.111% for HBV, 0.431% for HCV, 0.201% for HIV, 0.29% for syphilis, and 0.006% for MP). This aligns closely with the figures reported by Assessment of Blood Banks in 2016 for Delhi (2.03% TTI prevalence) and other nearby Northern Indian states like Punjab (2.64% TTI prevalence) and Haryana (1.97% TTI prevalence)[13].

The variation in TTI prevalence is notable across different states of India. For instance, the highest TTI prevalence rates in India were observed in Puducherry (3.13%) and Arunachal Pradesh (2.19%). In contrast, Kerala had one of the lowest rates at 0.56%[13]. This variability suggests that local factors such as healthcare infrastructure, blood donor screening processes, and population health may influence TTI prevalence rates[13].

On an international scale, the TTI prevalence also varies widely across different countries. Notable high prevalence rates were observed in Malawi, Kenya, and Ghana, with a combined rate of 10.7%, including 3.4% for HBV, 2.4% for HCV, and 2.4% for HIV[27]. Similarly, countries like Pakistan[21,22], Saudi Arabia[23], Ethiopia[24,25], and Brazil[26] also reported relatively high TTI prevalence rates compared to India and other nations (Table 3)[10,12-27].

In the present study, blood donors were stratified into in-house donors and camp donors. Camp donors were further divided into institutional camp donors and community camp donors. We found the lowest prevalence of TTIs among institutional camp donors, whereas the highest prevalence was noted among in-house donors. The institutions in the present study were mostly educational institutes (example, colleges and various government offices); there was a lower prevalence of TTIs among the students and employees of these institutes. Shrivastava et al[10] in their study found that seroprevalence rate of TTI was significantly higher (3.8%) in replacement donations compared to voluntary blood donors (2.3%). Similarly, Jain et al[11] found a higher prevalence of TTIs in family donors in comparison to voluntary donors.

In-house donors, being a heterogeneous group, include relatives of admitted patients. These donors, although highly motivated, had the highest prevalence of TTIs.

Among the camp donors, the prevalence of VDRL reactivity was significantly higher in community donors as compared to institutional donors.

The impact of education levels and socio-economic conditions of blood donors on the prevalence of TTI was not the focus of the present study. Moreover, the present study does not discuss strategies to enhance current screening technologies or donor counseling methods to reduce the risk of infected donations. These are few limitations of the present study. Future studies should explore these variables to gain a deeper understanding of their role in reducing TTIs among blood donors. Research into advanced screening techniques and more effective pre-donation counseling could lead to better outcomes in blood safety.

The data underscores the importance of continuous monitoring and effective screening programs for blood transfusions to minimize the transmission of TTIs. The differences in TTI prevalence rates across various donor groups and regions suggest the need for tailored approaches to blood safety measures and targeted interventions to address the health challenges. Further research of social–economic–health factors is essential to improve blood safety and reduce the risk of transfusion-related infections across diverse populations.

The work bears a sense of gratitude to Kumar N, Singh S, Anwar MF, Kumar N, Kumawat S, Kumar L, Kumar V, Kumar S, Singh K, Kumar S, Ali, Kumar M, and other staff of Hindu Rao Hospital for their support.

| 1. | Bihl F, Castelli D, Marincola F, Dodd RY, Brander C. Transfusion-transmitted infections. J Transl Med. 2007;5:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Das S, Kumar M. Association of blood group types to hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors: A five years institutional based study. Int J Basic Appl. 2012;2:191-195. |

| 3. | Dong Y, Qiu C, Xia X, Wang J, Zhang H, Zhang X, Xu J. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection among HIV-1-infected injection drug users in Dali, China: prevalence and infection status in a cross-sectional study. Arch Virol. 2015;160:929-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Weldemhret L. Epidemiology and Challenges of HBV/HIV Co-Infection Amongst HIV-Infected Patients in Endemic Areas: Review. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2021;13:485-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kundisova L, Nante N, Martini A, Battisti F, Giovannetti L, Messina G, Chellini E. The impact of mortality for infectious diseases on life expectancy at birth in Tuscany, Italy. EJPH. 2020;30. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wali A, Khan D, Safdar N, Shawani Z, Fatima R, Yaqoob A, Qadir A, Ahmed S, Rashid H, Ahmed B, Khan S. Prevalence of tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and hepatitis; in a prison of Balochistan: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Samo AA, Laghari ZA, Baig NM, Khoso GM. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Hepatitis B and C in Nawabshah, Sindh, Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104:1101-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Alqahtani SA, Colombo M. Viral hepatitis as a risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res. 2020;6:58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khan MY, Sijjeel F, Khalid A, Khurshid R, Habiba UE, Majid H, Naeem M, Nawaz B, Nawaz B, Abbas S, Malik NUA. Prevalence of ABO and Rh blood groups and their association with Transfusion-Transmissible Infections (TTIs) among Blood Donors in Islamabad, Pakistan. BioSci Rev. 2021;3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Shrivastava M, Mishra S, Navaid S. Time Trend and Prevalence Analysis of Transfusion Transmitted Infections among Blood Donors: A Retrospective Study from 2001 to 2016. Indian J Community Med. 2023;48:274-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jain R, Gupta G. Family/friend donors are not true voluntary donors. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2012;6:29-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thakur SK, Singh S, Negi DK, Sinha AK. Prevalence of TTI among Indian blood donors. Bioinformation. 2023;19:582-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | A Report on the Assessment of Blood Banks in India. Delhi: NACO, NBTC, Ministry of Health, Welfare F, Government of India 2016. |

| 14. | Varma AV, Malpani G, Kosta S, Malukani K, Sarda B, Raghuvanshi A. Seroprevalence of transfusion transmissible infections among blood donors at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Central India. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2019;6:L1-L4. |

| 15. | Prakash S, Sahoo D, Mishra D, Routray S, Ray GK, Das PK, Mukherjee S. Association of transfusion transmitted infections with ABO and Rh D blood group system in healthy blood donors: a retrospective analysis. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2020;7:4444-8. |

| 16. | Sunderam S, Karir S, Haider S, Singh S, Kiran A. Sero-Prevalence of Transfusion Transmitted Infections among Blood Donors at Blood Bank of Rajendra Institute of Medical Sciences, Ranchi. Heal J of Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med. 2015;6:36-40. |

| 17. | Patel D, Shah RJ. Correlation of ABO-Rh blood group and transfusion transmitted infections (TTI) among blood donors. ACHR. 2022;7:229-232. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Bharadva S, Vachhani J, Dholakiya S. ABO and Rh association to transfusion transmitted infections among healthy blood donors in Jamnagar, Gujarat, India. J Res Med Den Sci. 2016;4:58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fatima A, Begum F, Kumar KM. Seroprevalence of Transfusion Transmissible Infections among Blood Donors in Nizamabad District of Telangana State-A Six Years Study. Int Arch Integ Med. 3:73-78. |

| 20. | Mohammadali F, Pourfathollah A. Association of ABO and Rh Blood Groups to Blood-Borne Infections among Blood Donors in Tehran-Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:981-989. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Batool Z, Durrani SH, Tariq S. Association Of Abo And Rh Blood Group Types To Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Hiv And Syphilis Infection, A Five Year' Experience In Healthy Blood Donors In A Tertiary Care Hospital. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29:90-92. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bhatti MM, Junaid A, Sadiq F. The Prevalence of Transfusion Transmitted Infections among Blood Donors in Pakistan: A Retrospective Study. Oman Med J. 2022;37:e386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Altayar MA, Jalal MM, Kabrah A, Qashqari FSI, Jalal NA, Faidah H, Baghdadi MA, Kabrah S. Prevalence and Association of Transfusion Transmitted Infections with ABO and Rh Blood Groups among Blood Donors in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia: A 7-Year Retrospective Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Legese B, Shiferaw M, Tamir W, Eyayu T, Damtie S, Berhan A, Getie B, Abebaw A, Solomon Y. Association of ABO and Rhesus Blood Types with Transfusion-Transmitted Infections (TTIs) Among Apparently Healthy Blood Donors at Bahir Dar Blood Bank, Bahir Dar, North West, Ethiopia: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. J Blood Med. 2022;13:581-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ataro Z, Urgessa F, Wasihun T. Prevalence and Trends of Major Transfusion Transmissible Infections among Blood Donors in Dire Dawa Blood bank, Eastern Ethiopia: Retrospective Study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28:701-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pessoni LL, Aquino ÉC, Alcântara KC. Prevalence and trends in transfusion-transmissible infections among blood donors in Brazil from 2010 to 2016. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2019;41:310-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Singogo E, Chagomerana M, Van Ryn C, M'bwana R, Likaka A, M'baya B, Puerto-Meredith S, Chipeta E, Mwapasa V, Muula A, Reilly C, Hosseinipour MC; Malawi BLOODSAFE Program. Prevalence and incidence of transfusion-transmissible infections among blood donors in Malawi: A population-level study. Transfus Med. 2023;33:483-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |