INTRODUCTION

Delirium is an acute consciousness disorder characterized by impaired orientation and the inability to accurately recognize people, places, spatial context, or time within the surrounding environment[1]. Patients often experience delusions and hallucinations, accompanied by emotional instability and impulsive behaviors. Notably, delirium symptoms are typically milder during the day but tend to intensify at night. Affected individuals may display daytime drowsiness and nighttime restlessness. Once consciousness is restored, patients often retain only fragmented memories of their delirium episodes or may lose recollection entirely.

Delirium is a clinical phenomenon that can arise in a wide array of conditions, including high fever, toxic systemic illnesses, and organic brain disorders. It is also frequently observed following surgical procedures, particularly after neurosurgical interventions[2]. The incidence of postoperative delirium (POD) varies depending on the surgical site and the techniques employed, with neurosurgery often associated with a higher prevalence compared to other types of surgeries[2-4]. As a specialty dedicated to the management of craniocerebral disorders, neurosurgery deals with patients who are typically in critical condition and often experience significant pain, psychiatric symptoms, or altered levels of consciousness. These factors collectively heighten the risk of complications, including delirium, in this vulnerable patient population[1,5,6].

Morshed et al[7] have conducted a study involving 235 patients undergoing craniocerebral surgery, revealing that 52 individuals (22.1%) develop POD. Their findings have identified key predictors of delirium, including advanced age (≥ 72.56 years), a postoperative intensive care unit (ICU) stay of 5 or more days, and neurological impairment either preoperatively or postoperatively. Furthermore, other studies have highlighted the severe consequences of delirium, such as prolonged hospitalization, hindered postoperative recovery, deterioration in physical and cognitive functions, and, in extreme cases, increased mortality[8,9]. This review aims to explore the current research on delirium following neurosurgical procedures, providing valuable insights to enhance clinical practice in neurosurgery.

CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF POD

Clinically, POD is classified into three subtypes: (1) Hyperactive type: This form is characterized by heightened alertness, pronounced irritability, hallucinations, delusions, and agitated behaviors. Patients with hyperactive POD are typically easy to identify due to the overt nature of their symptoms, facilitating timely diagnosis and intervention; (2) Hypoactive type: This subtype manifests as a significant reduction in activity levels and mental lethargy, particularly common among elderly patients. Despite its high prevalence in clinical settings, the subtlety of its symptoms often leads to delayed detection and frequent missed diagnoses. Consequently, this subtype is associated with the poorest prognoses among all POD types; and (3) Mixed type: This form alternates between symptoms of hyperactivity and hypoactivity, combining features of both subtypes.

Early recognition and accurate classification of POD are critical for implementing effective treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes. Currently, the diagnosis of delirium primarily relies on two authoritative frameworks in psychiatry: The International Classification of Diseases issued by the World Health Organization and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) issued by the American Psychiatric Association[13,14]. These diagnostic criteria are widely recognized and serve as essential references in clinical practice.

The DSM-5 outlines the clinical manifestations and diagnostic characteristics of delirium, which can be summarized into the following five key criteria: (1) Disturbances in attention and awareness: This includes a reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, or shift attention, as well as impaired awareness of the surrounding environment; (2) Acute onset and fluctuating course: Symptoms develop rapidly, typically within hours or days, and exhibit significant fluctuations in severity over the course of a single day; (3) Cognitive impairment: Patients may experience deficits in memory, orientation, language, visuospatial abilities, or sensory perception; (4) Exclusion of other conditions: The symptoms cannot be attributed to a pre-existing or evolving neurocognitive disorder and occur in the absence of coma; and (5) Identifiable cause: Evidence of an underlying cause, such as substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to toxins, or a combination of contributing factors, must be present[13].

Building upon the DSM-5 criteria, researchers have developed the 3-Minute Diagnostic Interview for Confusion Assessment Method to facilitate delirium screening. Designed for use by non-psychiatric clinicians and nurses, this tool demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy, with a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 94%[15]. The 3-Minute Diagnostic Interview for Confusion Assessment Method offers a practical and efficient approach for identifying delirium in diverse clinical settings, enabling timely intervention and improved patient care.

PATHOGENESIS OF POD

POD is an acute mental state characterized by altered consciousness and disrupted thought processes following surgery. This clinical syndrome not only prolongs hospital stays and escalates medical expenses but also imposes a substantial economic and psychological burden on families and society. Despite its significance, the precise pathogenesis of POD remains inadequately understood[16]. However, there is a growing consensus among researchers that the underlying mechanisms primarily involve the neurotransmitter imbalance theory and the inflammatory factor theory.

Neurotransmitter imbalance theory

The imbalance between acetylcholine and dopamine levels in the brain is considered a key factor in the development of POD[17,18]. Specifically, a decline in acetylcholine activity, coupled with an increase in dopamine levels, can disrupt normal neural processes, triggering delirium symptoms[19]. Excessive use of dopaminergic drugs, such as levodopa, has been shown to exacerbate this imbalance and induce delirium, particularly hyperactive or mixed-type delirium[20]. A rapid rise in dopamine concentrations within the central nervous system (CNS) is strongly associated with such presentations[17].

Acetylcholine plays an essential role in regulating learning, consciousness, and memory by binding to nicotinic receptors in the brain[18]. A reduction in acetylcholine levels often results in cognitive impairments, including memory loss and difficulties in maintaining attention. Additionally, monoamine neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), are critical in regulating mental states and emotions. Significant alterations in serotonin activity within the brain can further predispose patients to delirium[20]. Age-related physiological changes also contribute to this imbalance. As individuals age, the activity of choline acetyltransferase, the enzyme responsible for acetylcholine synthesis, declines, while acetylcholinesterase activity, responsible for acetylcholine degradation, remains relatively stable. This imbalance leads to a pronounced reduction in acetylcholine levels, accompanied by elevated dopamine activity, creating conditions conducive to the onset of delirium symptoms.

Inflammatory factor theory

The inflammatory factor theory posits that acute inflammatory responses, triggered by surgery, trauma, or infections, play a critical role in the pathogenesis of POD. These responses can damage vascular endothelial cells, impairing the functional integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and significantly increasing its permeability[11,21]. Under such conditions, inflammatory mediators in the peripheral circulation, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and C-reactive protein, are able to penetrate the compromised BBB and enter the CNS[11]. This infiltration activates microglia and astrocytes, thereby triggering CNS inflammation[9]. This process is particularly pronounced in elderly individuals, where microglia often remain in a pre-activated state. Consequently, the peripheral inflammatory response more readily induces CNS inflammation in this population, increasing their susceptibility to delirium[22].

Once inflammatory mediators invade the CNS, they can disrupt brain function by causing ischemia and hypoxia in neural cells. This dysfunction, in turn, exacerbates BBB permeability, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of damage. The resulting inflammatory cascade further amplifies CNS inflammation, ultimately disrupting normal brain function and precipitating delirium symptoms[18]. A study by Yamanashi et al[16] highlights the role of epigenetic changes in this process. Their genetic analysis has revealed that neurosurgical procedures significantly alter DNA methylation levels at key CpG sites on pro-inflammatory genes, including 17 out of 24 sites on the tumor necrosis factor gene, 8 out of 14 sites on the IL1B gene, and 4 out of 14 sites on the IL6 gene. These findings underscore the potential role of inflammation and epigenetic mechanisms in the development of delirium. Additionally, some researchers suggest that structural and functional brain injuries, along with other contributing factors, may also play a role in the pathogenesis of trauma-induced delirium[18].

RISK FACTORS FOR DELIRIUM IN NEUROSURGERY

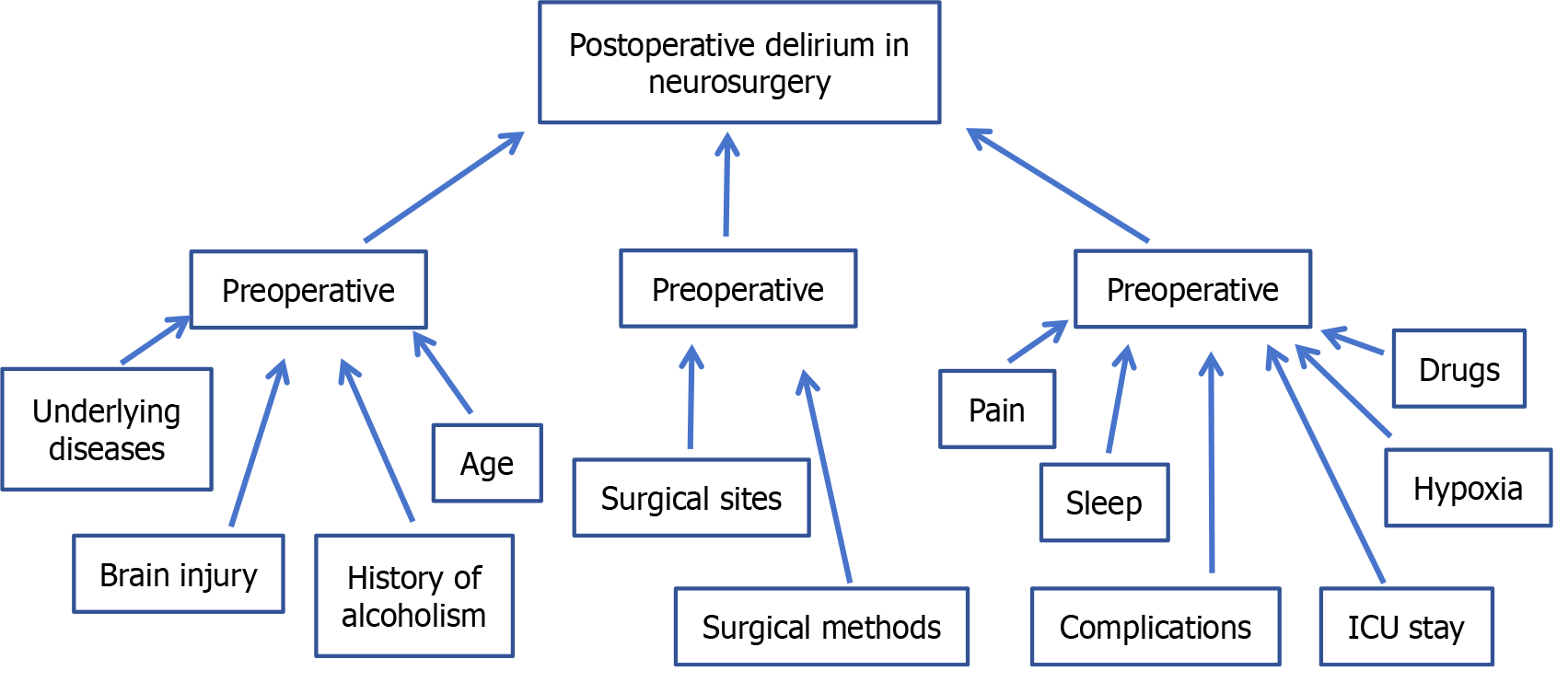

The occurrence of POD is caused by the comprehensive influence of multiple factors, and its risk factors can be divided into three stages: Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative according to the operative time node (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Risk factors for postoperative delirium in neurosurgery.

ICU: Intensive care unit.

Preoperative risk factors related to POD

Previous studies have shown that the most common risk factors before POD operation are old age and gender[23,24]. For patients undergoing craniocerebral surgery, in addition to the above risk factors, drugs, infection, vascular complications, hypoxia, electrolyte imbalance and paraneoplastic syndrome may increase the incidence of POD[1,23,25,26].

Age: A meta-analysis authored by Kappen et al[8] has indicated that advanced age is an independent risk factor for POD among patients. In the elderly, a series of alterations in brain function occur during the aging process, including changes in stress-regulating neurotransmitters, decreased cerebral blood flow, neuronal apoptosis, and alterations in cellular signaling systems, all of which contribute to an increased susceptibility to delirium. Additionally, Yoo et al[23] observed that among 153 patients undergoing surgery for brain metastases, those of advanced age were more prone to experiencing POD.

Underlying diseases: The underlying diseases of patients, such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease and cerebral infarction, are correlated with postoperative mental disorders[23,24,27]. For patients with cardiopulmonary insufficiency, cerebral blood perfusion levels tend to decrease while airway resistance increases, further exacerbating the risk of cerebral hypoxia. Relevant studies have shown that dysfunction of heart, lung, liver, kidney and other organs combined with hypertension or diabetes are independent risk factors for POD[27]. Another study pointed out that after patients experienced hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, their cerebral arteries were often accompanied by different degrees of atherosclerosis, resulting in increased vulnerability of the CNS[28]. For patients with multiple organ dysfunction, under the stimulation of multiple factors such as cranial injury, anesthesia and surgery, delirium symptoms including delusion, hallucination and memory disorders are more likely to occur.

Preoperative brain injury: The degree of preoperative brain injury is associated with the occurrence of POD. Li et al[1] proposed that brain tumor patients were at high risk of POD. The existence of tumors would damage brain tissue structure and lead to functional abnormalities, and the probability of POD would be higher. They also proposed that in a study of 916 patients undergoing brain tumor resection, the pathological type of the tumor was also a risk factor for the occurrence of POD, and different brain tumor pathology had different effects on the damage of brain tissue and the occurrence of POD.

Anatomic location of craniocerebral lesions: Studies have found that the anatomic location of craniocerebral lesions is correlated with the occurrence of POD. The incidence of POD is relatively high in patients with pituitary or hypothalamic lesions, which may be related to the predisposition of lesions in this region to cause hyponatremia. Yoo et al[23] conducted a more in-depth study on this phenomenon with the help of magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging technology. The results show that there is a close correlation between the occurrence and severity of POD and the damage of cerebellum, hippocampus, thalamus and basal ganglia caused by hemorrhage or tumor. In addition, the prospective study conducted by Naidech et al[29] on patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage also pointed out that the incidence of POD was higher when intracerebral hematoma was located in the subcortical or parahippocampal regions of the cerebral hemisphere compared with other sites.

History of alcoholism: According to the results of Kanova et al[30], alcoholism is an independent risk factor for POD. Specifically, alcohol can cause brain cell metabolic dysfunction, which in turn leads to a decrease in the ability of the cerebral cortex to receive information from the brain, and ultimately leads to the appearance of delirium.

Intraoperative risk factors associated with POD

There is a direct correlation between the occurrence of POD and the operation. The intervention site, duration of operation and anesthesia, selection of anesthetic drugs, intraoperative blood loss, and occurrence of hypoxia or hypotension events are all related to the occurrence of POD[24,31]. In addition, cerebral hypoperfusion and cerebral ischemia have also been identified as important causes of POD[28].

The incidence of POD may be higher in neurosurgery than in other surgical procedures: During neurosurgery, procedures may lead to cerebral hypoperfusion and ischemia in patients, such as intraoperative brain tissue pulling and lesion resection, which may cause cerebral tissue edema and ischemia, which may lead to severe functional effects and POD. For neurosurgery, the incidence of POD may be higher than in other specialties due to the longer operation time and the relatively difficult management of the depth of anesthesia during surgery. The risk of POD incidence in neurosurgery has been reported in several literatures[23].

Different surgical sites may cause different incidence of POD: Yoo et al[23] found that tumor location has an important effect, and patients with cerebellar metastasis seem to be more prone to psychosis, and this finding is consistent with previous evidence that abnormal diffusion tensor imaging of the cerebellar is the most important risk factor for postoperative psychosis. Wang et al[19] pointed out that tumor location in temporal lobe is an independent risk factor for POD after supratentorial tumor resection. They also mention that a retrospective cohort study showed that tumors invading both cerebral hemispheres and tumors larger than 5 cm in diameter were also risk factors for POD[19]. In addition, other studies have pointed out that tumors located in the frontal and temporal lobes may lead to different degrees of cognitive impairment, thereby inducing POD[32].

Different surgical methods may result in different incidence of POD: Studies have shown that the choice of surgical method has a significant impact on the incidence of POD for the same disease. Wang et al[19] pointed out independent risk factors for POD after resection of supratentorial tumor by frontal approach neurosurgery. The study of Wang et al[33] also reached a similar conclusion, that is, frontal approach craniotomy is an independent risk factor for POD in ICU patients after neurosurgery. The study of Latimer et al[34] compared the cognitive dysfunction after endovascular embolization of ruptured intracranial aneurysms and cervical clipping, and the results showed that the incidence of POD after endovascular intervention was significantly lower than that after cervical clipping. Kappen et al[8] found that patients receiving neurovascular surgery had the highest incidence of delirium (42%), and the incidence of delirium under different surgical methods was different.

Risk factors of delirium after surgery

The risk factors associated with POD surgery include pain, sleep disturbance, sedation and analgesic drug use, mechanical ventilation duration, ICU stay, and electrolyte disturbance[1,35,36].

Postoperative pain: Pain is a response to injurious stimuli to the body. When the pain persists, it may trigger emotional reactions such as anxiety, tension and fear, which in turn lead to disorders of physiological functions. One study pointed out that there was a positive correlation between the release of inflammatory factors induced by postoperative pain and the occurrence of delirium[35]. In neurosurgery, due to the invasive nature of the operation, the patient’s body will be subjected to severe pain stimulation, which activates the autoimmune system and triggers a strong peripheral inflammatory response. At the same time, the inflammatory factors released by these inflammatory responses will directly or indirectly affect the CNS, leading to the occurrence of delirium[31]. In addition, Jin et al[36] also found that there was a correlation between the degree of postoperative pain and POD, and appropriate postoperative analgesia measures were helpful in preventing POD in neurosurgery. As the postoperative pain is more intense, patients often show tension, anxiety and other negative emotions, which further aggravate the physiological dysfunction of patients, thereby increasing the risk of delirium.

Postoperative sleep status: The incidence of postoperative neurological dysfunction, especially delirium, is significantly correlated with sleep dysfunction. It is often difficult for patients to quickly adapt to the changes in the living environment after hospitalization, and the implementation of various postoperative treatment measures, noise interference in the ward and the influence of lighting and other factors may become important factors inducing delirium. In addition, postoperative pain can directly have a negative impact on patients’ sleep duration and sleep quality. A systematic review study by Fadayomi et al[37] pointed out that postoperative sleep disturbances in patients can increase the incidence of POD. Due to the particularity of the ICU environment, including the presence of 24-hour staff, a large number of monitoring instruments issued by the buzzer alarm sound and confined space, most patients will have sleep disorders after surgery. In addition, some neurosurgical procedures, especially those involving key parts such as the brain stem and hypothalamus, will affect the sleep and wake center of patients, thus further aggravating the degree of postoperative sleep disorders in neurosurgical patients.

Use of sedative and analgesic drugs: Existing studies have confirmed that drugs can effectively relieve the pain of patients with craniocerebral injury and improve their vital signs[38], thus achieving effective prevention and control of delirium. However, if the medication is not used properly, delirium symptoms may be induced. Improper use of benzodiazepines, such as midazolam or lorazepam, especially improper control of drug dosage, has been considered as one of the risk factors for ICU delirium[39]. A randomized controlled trial of 619 elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery showed that intraoperative administration of 0.5 μg/kg/hour dexmedetomidine significantly reduced the incidence of POD compared to normal saline[40]. According to He et al[41], early prophylactic use of dexmedetomidine within 24 hours after surgery can significantly reduce the incidence of agitation, which may include some symptoms of hyperactive delirium.

Postoperative hypoxia: Patients after neurosurgery, affected by many factors such as the state of consciousness, need to take bed rest. However, long-term bed rest may lead to a series of adverse consequences such as hypoxemia. According to literature[24,42], brain tissue is very vulnerable to damage under hypoxia, which leads to functional disorders of the CNS, specifically manifested as reduced acetylcholine content, increased dopamine concentration, imbalance between oxygen supply and oxygen consumption, hypoxic edema of brain tissue, which may eventually induce delirium. In addition, Yoo et al[23] pointed out that the neuronal hypoxia of peripheral brain cell tissues caused by intracranial related factors may be another important reason for the higher incidence of insanity in patients with intracranial hemorrhage after neurosurgery.

Postoperative ICU monitoring: In the ICU environment, patients are often highly alert due to unfamiliar environments, physical limitations, and the use of tracheal intubation. A study on the correlation between the environment of the neurological ICU and POD shows that there is a significant correlation between the level of environmental noise and the arousal frequency of patients, and environmental noise is a major factor leading to sleep disorders in patients, which may induce delirium[12]. Other studies pointed out that patients receiving treatment in ICU generally experienced sleep disruption, and it was difficult to ensure normal and effective sleep duration due to the interference of various sounds, light and treatment measures in the patient room[43]. In addition, delirium was significantly associated with factors such as physical restraint/immobilization, lower Glasgow Prognostic Scale score, prolonged ICU stay, and catheter insertion[8].

Complications such as bleeding after surgery: Postoperative complications such as bleeding in the operative area will lead to an increase in the incidence of delirium. Studies by Yoo et al[23] have shown a strong link between postoperative intracranial hemorrhage and the development of delirium. The study looked at 153 patients who underwent surgery for metastatic tumors and found that of the 14 patients who developed postoperative hematoma, 7 (50%) developed delirium[23]. Lu et al’s study also held a similar view[24].

In addition, severe traumatic brain injury can cause hypopituitarism and lead to the imbalance of hormone decomposition and anabolic process, thus inducing a series of neuroendocrine disorders such as hyperglycemia, hypernatremia, hyponatremia and abnormal cortisol secretion, which further accelerate the occurrence of POD[44].