Published online Apr 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.100650

Revised: January 1, 2025

Accepted: February 7, 2025

Published online: April 19, 2025

Processing time: 214 Days and 2.6 Hours

Antenatal depression is a disabling mental disorder among pregnant women and may cause adverse outcomes for both the mother and the offspring. Early identification and intervention of antenatal depression can help to prevent adverse outcomes. However, there have been few population-based studies focusing on the association of social and obstetric risk factors with antenatal depression in China.

To assess the sociodemographic and obstetric factors of antenatal depression and compare the network structure of depressive symptoms across different risk levels based on a large Chinese population.

The cross-sectional survey was conducted in Shenzhen, China from 2020 to 2024. Antenatal depression was assessed using the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), with a score of ≥ 13 indicating the presence of probable antenatal depression. The χ2 test and binary logistic regression were used to identify the factors associated with antenatal depression. Network analyses were conducted to investigate the structure of depressive symptoms across groups with different risk levels.

Among the 44220 pregnant women, the prevalence of probable antenatal depression was 4.4%. An age ≤ 24 years, a lower level of education (≤ 12 years), low or moderate economic status, having a history of mental disorders, being in the first trimester, being a primipara, unplanned pregnancy, and pregnancy without pre-pregnancy screening were found to be associated with antenatal depression (all P < 0.05). Depressive symptom networks across groups with different risk levels revealed robust interconnections between symptoms. EPDS8 ("sad or miserable") and EPDS4 ("anxious or worried") showed the highest nodal strength across groups with different risk levels.

This study suggested that the prevalence of antenatal depression was 4.4%. Several social and obstetric factors were identified as risk factors for antenatal depression. EPDS8 ("sad or miserable") and EPDS4 ("anxious or worried") are pivotal targets for clinical intervention to alleviate the burden of antenatal depression. Early identification of high-risk groups is crucial for the development and implementation of intervention strategies to improve the overall quality of life for pregnant women.

Core Tip: The present study aimed to assess the sociodemographic and obstetric factors of antenatal depression based on a large Chinese population. This study suggested that the prevalence of antenatal depression was 4.4%. Several social and obstetric factors were identified as risk factors for antenatal depression. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)8 ("sad or miserable") and EPDS4 ("anxious or worried") are pivotal targets for clinical intervention to alleviate the burden of antenatal depression. It is expected that this study can facilitate psychological intervention of women in early pregnancy, reduce the risk of prenatal depression, and mitigate the adverse impact of risk factors. Early identification of high-risk groups is crucial for the development and implementation of intervention strategies to improve the overall quality of life for pregnant women.

- Citation: He ZP, Cheng JZ, Yu Y, Wang YB, Wu CK, Ren ZX, Peng YL, Xiong JT, Qin XM, Peng Z, Mao WG, Chen MF, Zhang L, Ju YM, Liu J, Liu BS, Wang M, Zhang Y. Social and obstetric risk factors of antenatal depression: A cross-sectional study in China. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(4): 100650

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i4/100650.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.100650

Pregnant women experience a variety of mental and physical changes, making them more likely to have mental health problems[1]. Antenatal depression is one of the most common mental disorders among pregnant women and is considered a major public health issue due to its impacts and consequences[2]. Antenatal depression affects both the pregnant women and their fetuses[3]. Although the consequences of antenatal depression, such as increased risks of postpartum depression[4], preterm birth[5], and delayed cognitive development in children, are well-documented, a comprehensive understanding of the risk factors contributing to its prevalence remains underexplored, particularly in China.

Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics are associated with the occurrence and development of depression among pregnant women[6-8]. Identifying the social and obstetric factors associated with antenatal depression is critical for facilitating effective early screening and intervention strategies. Moreover, insights into these risk factors can strengthen pre-pregnancy and antenatal care programs to address mental health challenges, an area often overlooked in China’s pre-pregnancy screening programs[9]. The continuity of antenatal and postpartum depression as well as the relationship between the mother’s depression and the offspring’s adverse outcomes also highlight the importance of the early detection and intervention of antenatal depression[3,10]. Hence, it is of great importance to look into antenatal depression in China.

Previous studies showed the essential role of social and obstetric characteristics on antenatal depression. However, many of these studies are based on small sample sizes, limiting the generalizability of their findings, and few have comprehensively assessed the symptom structure of antenatal depression across different risk levels. The study aims to address these gaps by investigating the prevalence of antenatal depression in China, identifying the social and obstetric risk factors, and comparing the network structure of depressive symptoms across risk levels. By focusing on a large population, this research provides robust evidence that informs early psychological interventions, reduces antenatal depression risks, and mitigates adverse maternal and child outcomes.

The questionnaire was designed with reference to the literature and reviewed by professors in gynecology and epidemiology. The questionnaire covered the following aspects: (1) Sociodemographic variables, including age (years), residence (temporary or permanent), employment status (unemployed or employed), level of education (years), subjective self-reported economic status (low, moderate or high), and any history of mental disorders (e.g., mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorders); and (2) Obstetric variables, including gestational weeks (first, second or third trimester), gravidity, parity, planned pregnancy (yes or no), mode of conception (natural or artificial), and regular pre-pregnancy screening (yes or no).

The 10-item Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used to assess the antenatal depression of the participants. EPDS is a self-reported scale assessing antenatal depressive symptoms over the past 7 days[11]. The total score of EPDS ranges from 0 to 30, calculated by summing up the scores of all items. In this study, a score of 13 or higher suggested probable antenatal depression, with a higher score indicating more symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.783 in this study, indicating good internal consistency.

Descriptive statistical analyses were used to analyze the demographic profile and the prevalence of probable antenatal depression. A reliability test was performed to evaluate the internal consistency of EPDS. Cross-tabulation with the Pearson χ2 test was used to assess the significance of differences in sociodemographic and obstetric variables between women with and without antenatal depression. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to examine the adjusted effect of risk factors for antenatal depression.

To examine the discrepancy in antenatal depressive symptoms across populations with different risk levels, we constructed psychosocial networks comprising ten nodes, each representing a specific depressive symptom in the EPDS. The network structure was estimated using a mixed graphical model with extended Bayesian information criterion selection. Given the skewed nature of the data, rank transformations were applied using Spearman correlations as input during network estimation. Moreover, the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm was used to design the network layouts, ensuring that more interconnected nodes were positioned centrally while less connected nodes were positioned peripherally. Network strength was calculated to evaluate the relative importance of each node within the network. Network accuracy and stability were assessed using bootstrapping methods. Specifically, the significance of edge weights and centrality indices was tested. Additionally, edge weight and centrality difference tests were performed for each network to investigate differences between edge weights or centrality indices 12. Network comparison test was used to investigate whether the network properties, including global strength, network structure, and edge weights, differ by risk levels[12].

A factor with P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered significant in the analyses. All the data were analyzed using SPSS Version 25.0 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, United States) and R version 4.4.1.

A total of 44220 pregnant women were enrolled in this study. The sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 51 years. Over half of them (54%) were temporary residents, and almost all (97.9%) were employed. Only 16.9% had received a low level of education (≤ 12 years). A very small proportion of the participants (0.6%) were classified as being in a low economic status. About 1.0% of the participants had a history of mental disorders. Regarding obstetric factors, the proportion of women in their first, second, and third trimester was nearly equal (33.3% in the first trimester, 33.6% in the second trimester, and 33.0% in the third trimester). About half of the participants (51.6%) were multipara and 58.0% were primipara. The majority (72.3%) reported planned pregnancies, 93.0% conceived naturally, and 42.8% did not undergo any screening before pregnancy.

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Age (years) | 18-24 | 1764 | 4.0 |

| 24-29 | 16671 | 37.7 | |

| ≥ 30 | 25785 | 58.3 | |

| Missing data | 0 | 0 | |

| Residence | Temporary | 23857 | 54.0 |

| Permanent | 20363 | 46.0 | |

| Missing data | 0 | 0 | |

| Employment status | Unemployed | 220 | 0.5 |

| Employed | 43302 | 97.9 | |

| Missing data | 698 | 1.6 | |

| Education (years) | ≤ 12 | 7479 | 16.9 |

| > 12 | 36738 | 83.1 | |

| Missing data | 3 | 0 | |

| Economic status | Low | 279 | 0.6 |

| Moderate | 25338 | 57.3 | |

| High | 18440 | 41.7 | |

| Missing data | 163 | 0.4 | |

| History of mental disorders | Yes | 463 | 1.0 |

| No | 43666 | 98.8 | |

| Missing data | 91 | 0.2 | |

| Obstetric variables | |||

| Trimester of pregnancy | First | 14740 | 33.3 |

| Second | 14879 | 33.6 | |

| Third | 14601 | 33.0 | |

| Missing data | 0 | 0 | |

| Gravidity | 1 | 19271 | 43.6 |

| ≥ 2 | 22832 | 51.6 | |

| Missing data | 2117 | 4.8 | |

| Parity | 0 | 25650 | 58.0 |

| ≥ 1 | 16449 | 37.2 | |

| Missing data | 2121 | 4.8 | |

| Planned pregnancy | Yes | 31963 | 72.3 |

| No | 12092 | 27.3 | |

| Missing data | 165 | 0.4 | |

| Mode of conception | Natural | 41146 | 93.0 |

| Artificial | 2913 | 6.6 | |

| Missing data | 161 | 0.4 | |

| Pre-pregnancy screening | Yes | 25127 | 56.8 |

| No | 18924 | 42.8 | |

| Missing data | 169 | 0.4 | |

Of the 44220 pregnant women, 1956 scored 13 or higher on the EPDS, indicating that the overall prevalence of probable antenatal depression was 4.4%. The prevalence of probable antenatal depression was 6.9% in the first trimester, 3.3% in the second trimester, and 3.0% in the third trimester.

The univariate analysis using the χ2 test revealed that antenatal depression was associated with age, residence, level of education, economic status, history of mental disorders, trimester of pregnancy, whether the pregnancy was planned, mode of conception, and screening before pregnancy, whereas employment status, gravidity, and parity were not found to be associated with antenatal depression.

The prevalence of antenatal depression was higher among younger pregnant women (Table 2). With regard to residence, the odds of antenatal depression increased by 1.313 times [OR: 1.313 (95%CI: 1.197-1.441)] for those residing in Shenzhen city temporarily. Participants with less than 12 years of education were 1.421 times more likely to develop depression [OR: 1.421 (95%CI: 1.269-1.581)]. Economic status was also found to be associated with antenatal depression, with higher odds of depression observed in those with lower economic status [low: OR: 3.281 (95%CI: 2.157-4.993); moderate: OR: 1.939 (95%CI: 1.752-2.147)]. Pregnant women with a history of mental disorders were six times more likely to develop antenatal depression [OR: 6.478 (95%CI: 5.179-8.104)]. The first trimester of pregnancy was also associated with increased odds of antenatal depression [OR: 2.412 (95%CI: 2.151-2.705)]. Furthermore, women with unplanned pregnancies [OR: 1.532 (95%CI: 1.394-1.684)], natural conception [OR: 1.314 (95%CI: 1.071-1.611)], and pregnancy without pre-pregnancy screening [OR: 1.379 (95%CI: 1.260-1.510)] are also at a higher risk for antenatal depression.

| Variables | With antenatal depression | Without antenatal depression | Pearson χ2, P value | OR (95%CI) | |

| Sociodemographic factors | |||||

| Age (years) | 18-24 | 149 (8.4) | 1615 (91.6) | 87.012, P < 0.001 | 2.256 (1.886-2.699) |

| 25-29 | 794 (4.8) | 15877 (95.2) | 1.223 (1.112-1.345) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 1013 (3.9) | 24772 (96.1) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Residence | Temporary | 1180 (4.9) | 22677 (95.1) | 33.494, P < 0.001 | 1.313 (1.197-1.441) |

| Permanent | 776 (3.8) | 19587 (96.2) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Employment status | Employed | 1942 (4.5) | 41360 (95.5) | 0.002, P = 0.965 | 0.986 (0.522-1.863) |

| Unemployed | 10 (4.5) | 210 (95.5) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Education (years) | ≤ 12 | 432 (5.8) | 7047 (94.2) | 38.948, P < 0.001 | 1.421 (1.269-1.581) |

| > 12 | 1524 (4.1) | 35214 (95.9) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Economic status | Low | 25 (9.0) | 254 (91.0) | 181.796, P < 0.001 | 3.281 (2.157-4.993) |

| Moderate | 1393 (5.5) | 23945 (94.5) | 1.939 (1.752 -2.147) | ||

| High | 537 (2.9) | 17903 (97.1) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| History of mental disorders | Yes | 103 (22.2) | 360 (77.8) | 352.126, P < 0.001 | 6.478 (5.179-8.104) |

| No | 1848 (4.2) | 41844 (95.8) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Obstetric factors | |||||

| Trimester of pregnancy | First | 1021 (6.9) | 12719 (93.1) | 329.936, P < 0.001 | 2.412 (2.151-2.705) |

| Second | 498 (3.3) | 14381 (96.7) | 1.122 (0.985-1.279) | ||

| Third | 437 (3.0) | 14164 (97.0) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Gravidity | 1 | 839 (4.4) | 18432 (95.6) | 0.059, P = 0.808 | 1.021 (0.921-1.112) |

| ≥ 2 | 983 (4.3) | 21849 (95.7) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Parity | 0 | 1146 (4.5) | 24504 (95.5) | 3.105, P = 0.078 | 1.091 (0.990-1.203) |

| ≥ 1 | 676 (4.1) | 15773 (95.9) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Planned pregnancy | Yes | 1247 (3.9) | 30716 (96.1) | 78.996, P < 0.001 | 1 (Ref category) |

| No | 708 (5.9) | 11384 (94.1) | 1.532 (1.394-1.684) | ||

| Mode of conception | Natural | 1854 (4.5) | 39292 (95.5) | 6.922, P = 0.009 | 1.314 (1.071-1.611) |

| Artificial | 101 (3.5) | 2812 (96.5) | 1 (Ref category) | ||

| Pre-pregnancy screening | Yes | 966 (3.8) | 24161 (96.2) | 48.590, P < 0.001 | 1 (Ref category) |

| No | 989 (5.2) | 17935 (94.8) | 1.379 (1.260-1.510) | ||

The final binary logistic regression model (Table 3) showed that eight risk factors, i.e., an age younger than 24 years, a low education level (≤ 12 years), low or moderate economic status, history of mental disorders, being in the first trimester, being a primipara, unplanned pregnancy, and pregnancy without pre-pregnancy screening, were significantly associated with antenatal depression. Women under 24 years of age were nearly twice as likely to experience depressive symptoms [OR: 1.863 (95%CI: 1.518-2.286)]. Furthermore, women with a lower level of education [≤ 12 years; OR: 1.201 (95%CI: 1.055-1.367)] and low or moderate economic status [OR: 1.749 (95%CI: 1.578-1.938)] were also found at a higher risk of depression. A history of mental disorders also greatly increases the odds of depression [OR: 9.248 (95%CI: 7.190-11.895)]. Regarding obstetric variables, women in the first trimester were found to be at a twofold risk of developing antenatal depression [OR: 2.528 (95%CI: 2.244-2.848)]. Being a primipara [OR: 1.166 (95%CI: 1.006-1.353] and unplanned pregnancy [OR: 1.272 (95%CI: 1.136-1.424)] were associated with an increased risk of depression. Furthermore, antenatal depression was found more prevalent among those who did not receive screening before pregnancy [OR: 1.170 (95%CI: 1.051-1.304)]. Some risk factors, such as temporary residence and natural conception, were only significant in the univariate analysis but not in the binary logistic regression analysis, suggesting that these factors might be influenced by other variables in the regression model.

| Variable | B | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Age ≤ 24 years | 0.622 | 0.105 | 35.419 | < 0.001 | 1.863 | 1.518-2.286 |

| Residence - temporary | 0.038 | 0.055 | 0.484 | 0.487 | 1.039 | 0.932-1.158 |

| Employment status - unemployed | -0.081 | 0.332 | 0.059 | 0.807 | 0.922 | 0.481-1.767 |

| Education ≤ 12 years | 0.183 | 0.066 | 7.686 | 0.006 | 1.201 | 1.055-1.367 |

| Low or moderate economic status | 0.559 | 0.052 | 113.493 | < 0.001 | 1.749 | 1.578-1.938 |

| With a history of mental disorders | 2.224 | 0.128 | 300.024 | < 0.001 | 9.248 | 7.190-11.895 |

| Being in the first trimester | 0.927 | 0.061 | 233.377 | < 0.001 | 2.528 | 2.244-2.848 |

| First pregnancy | 0.095 | 0.070 | 1.852 | 0.174 | 1.100 | 0.959-1.262 |

| Primipara | 0.154 | 0.076 | 4.135 | 0.042 | 1.166 | 1.006-1.353 |

| Unplanned pregnancy | 0.240 | 0.058 | 17.436 | < 0.001 | 1.272 | 1.136-1.424 |

| Natural conception | 0.175 | 0.112 | 2.422 | 0.120 | 1.191 | 0.956-1.485 |

| Without pre-pregnancy screening | 0.157 | 0.055 | 8.161 | 0.004 | 1.170 | 1.051-1.304 |

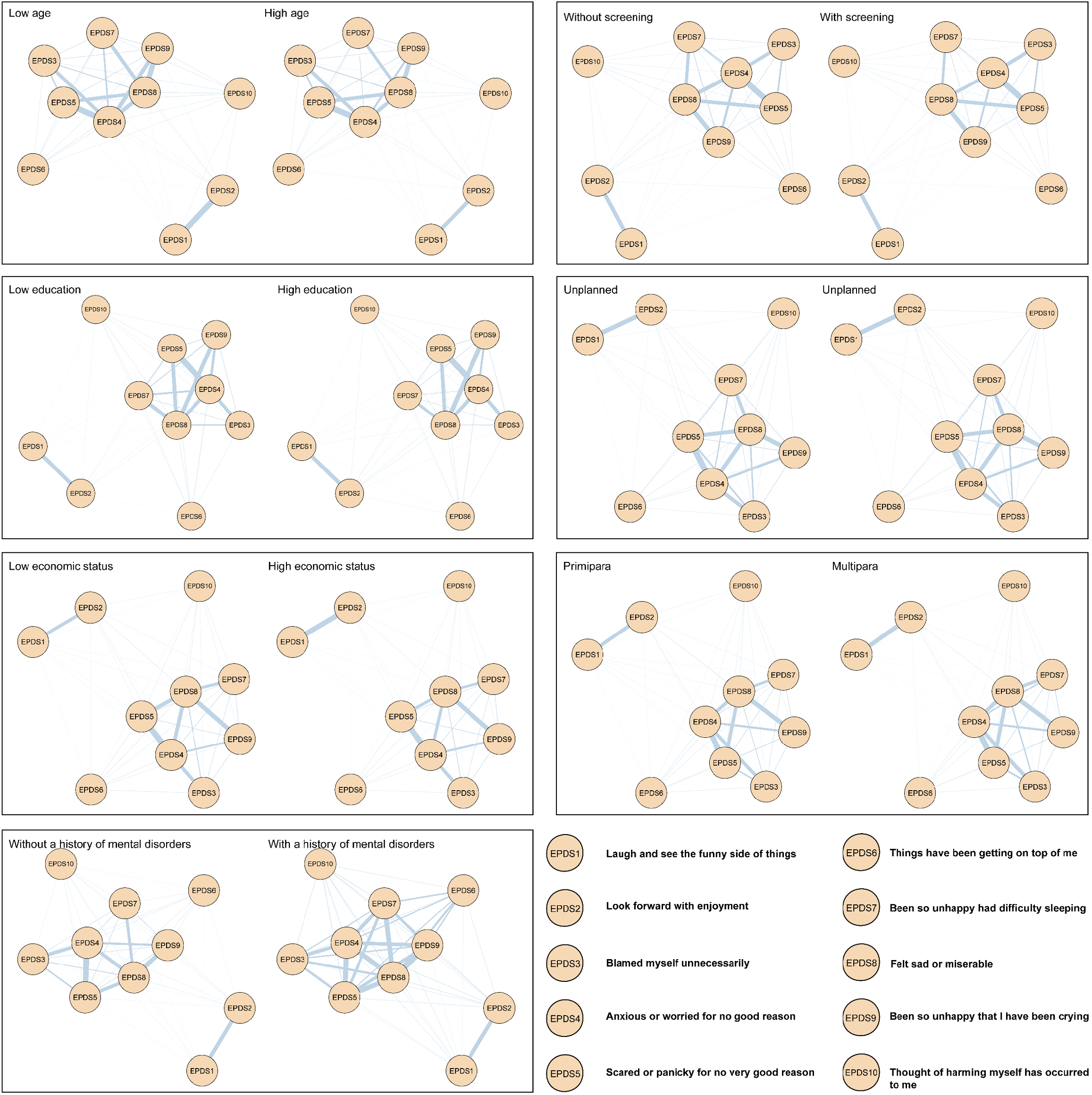

The antenatal depressive symptom networks in the groups with different risk levels are demonstrated in Figure 1. The grouping methods in the network analysis are consistent with those used in the logistic regression. The non-zero edges of the final network were 45 (100%) in all of the groups, which reflect robust interconnectedness between antenatal depressive symptoms. Estimated edge weights revealed positive correlations between each depressive symptom. The stability analysis revealed that most networks have good network structure stability, including network strength stability, edge weights, and centrality metrics (Supplementary Figures 1-56).

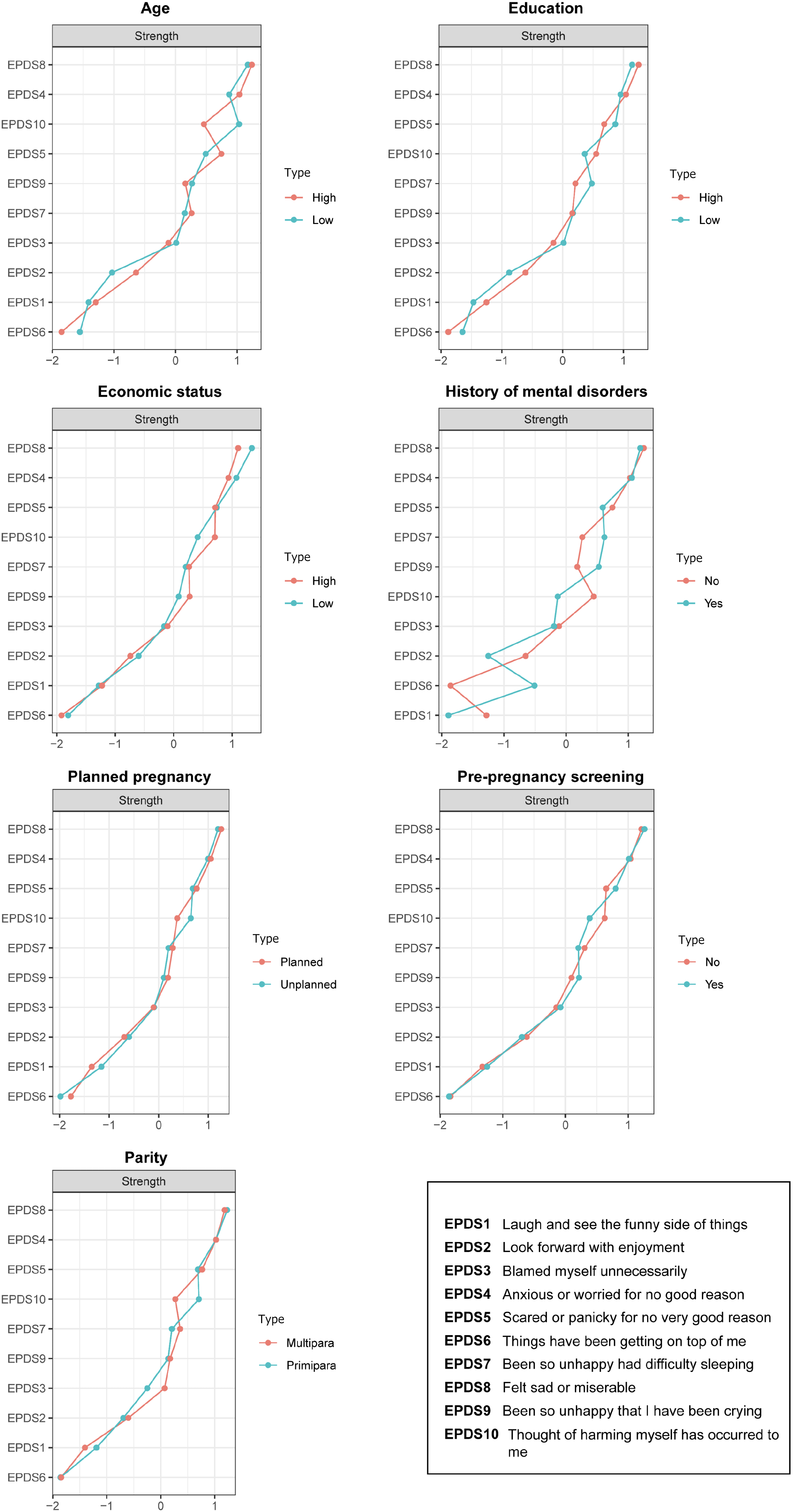

Regarding nodal strength, EPDS8 (“sad or miserable”) and EPDS4 (“anxious or worried”) had the highest strength in all but the low age groups (Figure 2). Notably, EPDS8 and EPDS10 (“suicidal thought”) were stronger than most other symptoms in the low age group, highlighting the significance of addressing suicidal ideation and behavior among younger pregnancies.

The global strength and maximum edge weight of networks in the groups with different risk levels are shown in Supplementary Figures 57-70 and Supplementary Tables 1-7. The global strength invariance test revealed that the overall intensity was higher in the low economic group (low economic level: 3.71 vs high economic level: 3.64, S = 0.08, P = 0.03), primipara group (primipara: 3.74 vs multipara: 3.62, S = 0.12, P < 0.01), unplanned pregnancy group (unplanned: 3.75 vs planned: 3.65, S = 0.10, P = 0.02), and the group without pre-pregnancy screening (without screening: 3.74 vs with screening: 3.65, S = 0.09, P = 0.02). In contrast, no significant differences in the overall intensity were observed between age groups (low age: 3.69 vs high age: 3.68, S = 0.01, P = 0.92), education groups (low education: 3.63 vs high education: 3.71, S = 0.08, P = 0.17), and groups with or without a history of mental disorders (without a history of mental disorders: 3.67 vs with a history of mental disorders: 4.03, S = 0.36, P = 0.23).

The edge weights showed significant differences in the economic groups (low economic level vs high economic level, M = 0.08, P < 0.001) and the groups with and without pre-pregnancy screening (without screening vs with screening, M = 0.03, P = 0.41). No statistical differences of edge weights were observed in the age groups (low age vs high age, M = 0.09, P = 0.18), the education groups (low education vs high education, M = 0.04, P = 0.26), planned- and unplanned- pregnancy groups (unplanned vs planned, M = 0.02, P = 0.55), groups with and without a history of mental disorders (without a history of mental disorders vs with a history of mental disorders, M = 0.15, P = 0.23), and primipara and multipara groups (primipara vs multipara, M = 0.04, P = 0.08).

The study reported that the prevalence of probable antenatal depression among pregnant women was 4.4%, which is lower than the observations of other studies based in China[13,14]. This might be related to the study site, which is Shenzhen, a city with better economic conditions than many other areas; the better living condition was a protective factor for pregnant women. Furthermore, this study was conducted during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, which might have resulted in a higher incidence of mental disorders among expectant mothers. Differences in the cutoff point for the EPDS scale used to define antenatal depression might also have contributed to differences in the prevalence across studies.

The present study found that antenatal depression was more prevalent among women aged below 24 years, with higher risks found among younger pregnant women. This finding aligns with a study conducted in South India, where younger women were twice as likely to develop antenatal depression [OR: 2.01 (95%CI: 0.56-7.20)][13]. However, some studies presented opposite results, indicating that older maternal age might contribute to a higher prevalence of antenatal depression[13,16]. A potential explanation for these differences is that younger women may struggle with the lack of experience in pregnancy and the demands of impending motherhood while older women may experience depression due to their reproductive history[17]. These contradictory findings highlight the need for further research to explore the relationship between maternal age and antenatal depression.

It has been found that a lower level of education is linked to a higher prevalence of antenatal depression, which is also supported by a study based in South China[6]. The study found that women who completed high school or lower education had nearly doubled odds of experiencing depression during pregnancy [OR: 1.848 (95%CI: 1.089-3.138)] compared to those who completed undergraduate or higher education. Similar findings have been reported in a prospective multi-center cohort study in Chengdu, China, and a separate meta-analysis[9,16]. A reason for this association could be that women with lower education levels might have less access to reliable information about pregnancy, leading to increased anxiety and concerns about their own health and the safety of their unborn children.

In line with the present study, many prior studies found that lower or moderate economic status could lead to an increasing incidence of antenatal depression[18]. A lower income is considered a major risk factor for antenatal depression. A meta-analysis suggests that pregnant women with financial difficulties are at a higher risk of developing depression[14], with almost doubled odds of depression [OR: 1.87 (95%CI: 1.25-2.78)] compared to those without such difficulties. A study based in Italy highlighted the protective effect of good economic conditions against depression during pregnancy, showing a nearly fivefold reduction in the odds of antenatal depression among women in good financial situations [OR: 0.23 (95%CI: 0.10-0.54)]. Similar findings have also been reported in studies based in the Netherlands[19]. Lower socioeconomic status can amplify the impact of previous negative life events, potentially increasing the risk of antenatal depression[19].

The study indicated that pregnant women in the first trimester had the highest rate of antenatal depression (6.9%), followed by those in the second trimester (3.3%) and the third trimester (3.0%). These findings are consistent with previous studies[20,21]. The role transition to motherhood may induce stress and low mood, which leads to a high prevalence of antenatal depression in the first trimester. In addition, approximately two-thirds of pregnant women experience nausea or vomiting, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy[22]. Women with nausea or vomiting are around eight times more likely to suffer from antenatal depression and four times more likely to have postnatal depression[23]. Vaginal bleeding, which occurs in approximately one-fourth of pregnant women in the first trimester, is associated with an increased risk of antenatal depression[24]. As the inadaptation gradually fades away as the pregnancy progresses, the prevalence of antenatal depression can become lower in the second and third trimesters.

The present study suggested that primiparas are more likely to develop antenatal depression. Interestingly, prior studies based on China and other regions suggest the opposite, showing that higher parity is linked to an increased prevalence of antenatal depression[13,25,26]. The disparities might be attributed to different sociodemographic characteristics between subject groups and different sampling methods. The higher social capital of pregnant women in Shenzhen might also be associated with a lower proportion of multipara than that of primipara[27]. Pregnant women in economically advanced cities have better access to medical resources and services, which gives multiparas more confidence during pregnancy.

The present study also found that unplanned pregnancy was associated with an increased odds of developing antenatal depression. This is consistent with a prospective longitudinal study conducted in Macau, which showed that women with unplanned pregnancies were nearly twice [OR: 1.86 (95%CI: 1.40-2.47)] as likely to report symptoms of depression[28]. Similar conclusions were reached in multicenter cross-sectional surveys based in South China and Hong Kong[6,29]. In a systematic review, unplanned pregnancy is considered an important risk factor for antenatal depression[30]. Unplanned pregnancy may lead to later beginning of antenatal classes and less communication with family and friends about pregnancy[28,31]. Moreover, unintended pregnancy is also associated with the sudden discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for women with depression or anxiety, leading to the deterioration of their mental health[32].

The present study also revealed that pregnancy without pre-pregnancy screening might be a risk factor leading to antenatal depression. Adequate pre-pregnancy testing may represent good physical and mental preparation for a newborn baby. According to a meta-analysis of studies in Mainland China, better preparation for a newborn baby has a positive effect on women’s mental health during pregnancy[16].

The network analysis of depressive symptoms across groups with different risk levels revealed robust interconnections between symptoms, with 100% of the non-zero edges present across all groups. EPDS8 ("sad or miserable") and EPDS4 ("anxious or worried") consistently exhibited the highest nodal strength, indicating their critical roles in antenatal depression. These symptoms are pivotal targets for clinical intervention to alleviate the burden of antenatal depression. Notably, EPDS10 ("suicidal thought") exhibited higher strength in younger pregnancies, underscoring the need for specialized support for younger expectant mothers, particularly concerning suicidal ideation and behavior.

The study found that global network strength was significantly higher among groups with low economic levels, primiparas, unplanned pregnancies, and those without pre-pregnancy screening. These findings align with prior evidence linking these sociodemographic and obstetric factors to increased vulnerability to depression[33]. For example, the primipara group exhibited heightened global strength, likely due to heightened uncertainty and stress associated with first-time motherhood[27]. Similarly, women with unplanned pregnancies faced higher global network strength, consistent with prior research suggesting that unintended pregnancies exacerbate psychological distress[34]. Interestingly, age and educational attainment did not show significant differences in global network strength, which contrasts with earlier studies that highlighted their influence. This discrepancy warrants further longitudinal investigations to understand how these factors dynamically interact with depressive symptoms.

The present study is of great importance as there is an urgent need to improve psychological care for pregnant women in China. However, there are still limited studies focusing on antenatal depression in different trimesters. To our knowledge, this study represents the largest cross-sectional investigation of antenatal depression in China. Furthermore, the regression model helped to identify factors associated with antenatal depression, thereby assisting in the identification of high-risk groups at an early stage. These findings underscored the importance of early mental health education and regular antenatal care, and policies are also needed to address mental health needs in primary health systems. The associations between antenatal depression and risk factors such as the first trimester, being a primipara, unplanned pregnancy, and pregnancy without pre-pregnancy screening indicate that more attention should be given to individuals with one or more of the above features. Additionally, our findings may provide a basis for healthcare professionals to integrate mental health services with maternal and child health services to provide appropriate support to and prevent antenatal and postpartum depression among pregnant women.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, all samples were sourced from Shenzhen Bao’an District Maternal and Child Health Hospital, which might have limited the generalizability of the findings. Including samples from the community might provide a more accurate estimate of prevalence. Furthermore, data from Shenzhen may not fully represent the national data about antenatal depression in China. Large-scale or nationwide studies are needed to achieve a comprehensive understanding. Secondly, the study utilized a cross-sectional design, capturing data at a single point in time, which precluded us from establishing a causality between antenatal depression and related factors. Further research is needed to address the above limitations by examining the factors longitudinally, particularly the dynamic changes through different trimesters.

The findings of the present study indicate that the prevalence of probable antenatal depression was 4.4%. Social and obstetric factors including an age of 24 years or younger, a low level of education (≤ 12 years), low or moderate economic status, a history of mental disorders, being in the first trimester, being a primipara, unplanned pregnancy, and pregnancy without pre-pregnancy screening were associated with antenatal depression. EPDS8 ("sad or miserable") and EPDS4 ("anxious or worried") exhibited the highest nodal strength across groups with different risk levels, which are pivotal targets for clinical intervention to alleviate the burden of antenatal depression. Incorporation of these factors into the screening of antenatal depression and early identification of high-risk groups is essential for improving the well-being and quality of life of pregnant women.

| 1. | Ayano G, Tesfaw G, Shumet S. Prevalence and determinants of antenatal depression in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0211764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sharapova A, Goguikian Ratcliff B. Psychosocial and Sociocultural Factors Influencing Antenatal Anxiety and Depression in Non-precarious Migrant Women. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dahiya N, Aggarwal K, Kumar R. Prevalence and correlates of antenatal depression among women registered at antenatal clinic in North India. Tzu Chi Med J. 2020;32:267-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brummelte S, Galea LA. Postpartum depression: Etiology, treatment and consequences for maternal care. Horm Behav. 2016;77:153-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, Howard LM, Pariante CM. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384:1800-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1206] [Cited by in RCA: 1387] [Article Influence: 126.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xiao J, Xiong R, Wen Y, Liu L, Peng Y, Xiao C, Yin C, Liu W, Tao Y, Jiang F, Li M, Luo W, Chen Y. Antenatal depression is associated with perceived stress, family relations, educational and professional status among women in South of China: a multicenter cross-sectional survey. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1191152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen J, Cross WM, Plummer V, Lam L, Sun M, Qin C, Tang S. The risk factors of antenatal depression: A cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:3599-3609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cheng J, Peng Y, Xiong J, Qin X, Peng Z, Mao W, Li H, Wang M, Zhang L, Ju Y, Liu J, Yu Y, Liu B, Zhang Y. Prevalence and risk factors of antenatal depression in the first trimester: A real-world cross-sectional study in a developed district in South China. J Affect Disord. 2024;362:853-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang X, Wang Y, Wang Y, Guo X, Zhang L, Wang W, Shen J. Prevalence and factors associated with trajectories of antenatal depression: a prospective multi-center cohort study in Chengdu, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dadi AF, Miller ER, Bisetegn TA, Mwanri L. Global burden of antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord. 1996;39:185-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Borkulo C, Boschloo L, Borsboom D, Penninx BW, Waldorp LJ, Schoevers RA. Association of Symptom Network Structure With the Course of [corrected] Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1219-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 51.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khanam R, Applegate J, Nisar I, Dutta A, Rahman S, Nizar A, Ali SM, Chowdhury NH, Begum F, Dhingra U, Tofail F, Mehmood U, Deb S, Ahmed S, Muhammad S, Das S, Ahmed S, Mittal H, Minckas N, Yoshida S, Bahl R, Jehan F, Sazawal S, Baqui AH. Burden and risk factors for antenatal depression and its effect on preterm birth in South Asia: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0263091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dadi AF, Wolde HF, Baraki AG, Akalu TY. Epidemiology of antenatal depression in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Prabhu S, Guruvare S, George LS, Nayak BS, Mayya S. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Antenatal Depression among Pregnant Women Attending Tertiary Care Hospitals in South India. Depress Res Treat. 2022;2022:9127358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nisar A, Yin J, Waqas A, Bai X, Wang D, Rahman A, Li X. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:1022-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kasujja M, Omara S, Senkungu N, Ndibuuza S, Kirabira J, Ibe U, Barankunda L. Factors associated with antenatal depression among women attending antenatal care at Mubende Regional Referral Hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2024;24:195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Míguez MC, Vázquez MB. Risk factors for antenatal depression: A review. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11:325-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Verbeek T, Bockting CLH, Beijers C, Meijer JL, van Pampus MG, Burger H. Low socioeconomic status increases effects of negative life events on antenatal anxiety and depression. Women Birth. 2019;32:e138-e143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hu J, Wan N, Ma Y, Liu Y, Liu B, Li L, Liu C, Qiao C, Wen D. Trimester-specific association of perceived indoor air quality with antenatal depression: China Medical University Birth Cohort Study. Indoor Air. 2022;32:e13167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Castro e Couto T, Cardoso MN, Brancaglion MY, Faria GC, Garcia FD, Nicolato R, de Miranda DM, Corrêa H. Antenatal depression: Prevalence and risk factor patterns across the gestational period. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:70-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Flaxman SM, Sherman PW. Morning sickness: a mechanism for protecting mother and embryo. Q Rev Biol. 2000;75:113-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mitchell-Jones N, Lawson K, Bobdiwala S, Farren JA, Tobias A, Bourne T, Bottomley C. Association between hyperemesis gravidarum and psychological symptoms, psychosocial outcomes and infant bonding: a two-point prospective case-control multicentre survey study in an inner city setting. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e039715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mei H, Li N, Li J, Zhang D, Cao Z, Zhou Y, Cao J, Zhou A. Depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychosom Res. 2021;149:110586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nisarga V, Anupama M, Madhu KN. Social and obstetric risk factors of antenatal depression: A cross-sectional study from South-India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;72:103063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rodríguez-Muñoz MF, Marcos-Nájera R, Amezcua MD, Soto-Balbuena C, Le HN, Al-Halabí S. "Social support and stressful life events: risk factors for antenatal depression in nulliparous and multiparous women". Women Health. 2024;64:216-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhou C, Ogihara A, Chen H, Wang W, Huang L, Zhang B, Zhang X, Xu L, Yang L. Social capital and antenatal depression among Chinese primiparas: A cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lau Y, Htun TP, Kwong HKD. Sociodemographic, obstetric characteristics, antenatal morbidities, and perinatal depressive symptoms: A three-wave prospective study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0188365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lau Y, Keung DW. Correlates of depressive symptomatology during the second trimester of pregnancy among Hong Kong Chinese. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1802-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 105.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yanikkerem E, Ay S, Piro N. Planned and unplanned pregnancy: effects on health practice and depression during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Roca A, Imaz ML, Torres A, Plaza A, Subirà S, Valdés M, Martin-Santos R, Garcia-Esteve L. Unplanned pregnancy and discontinuation of SSRIs in pregnant women with previously treated affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:807-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yin X, Sun N, Jiang N, Xu X, Gan Y, Zhang J, Qiu L, Yang C, Shi X, Chang J, Gong Y. Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;83:101932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rtbey G, Andualem F, Nakie G, Takelle GM, Mihertabe M, Fentahun S, Melkam M, Tadesse G, Birhan B, Tinsae T. Perinatal depression and associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |