Published online Jan 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i1.98630

Revised: October 6, 2024

Accepted: October 14, 2024

Published online: January 19, 2025

Processing time: 103 Days and 1 Hours

At present, the influencing factors of social function in patients with residual depressive symptoms are still unclear. Residual depressive symptoms are highly harmful, leading to low mood in patients, affecting work and interpersonal communication, increasing the risk of recurrence, and adding to the burden on families. Studying the influencing factors of their social function is of great significance.

To explore the social function score and its influencing factors in patients with residual depressive symptoms.

This observational study surveyed patients with residual depressive symptoms (case group) and healthy patients undergoing physical examinations (control group). Participants were admitted between January 2022 and December 2023. Social functioning was assessed using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), and scores were compared between groups. Factors influencing SDS scores in patients with residual depressive symptoms were analyzed by applying multiple linear regression while using the receiver operating characteristic curve, and these factors’ predictive efficacy on social function impairment was assessed.

The SDS scores of the 158 patients with depressive symptoms were 11.48 ± 3.26. Compared with the control group, the SDS scores and all items in the case group were higher. SDS scores were higher in patients with relapse, discontinuous medication, drug therapy alone, severe somatic symptoms, obvious residual symptoms, and anxiety scores ≥ 8. Disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, and residual symptoms correlated positively with SDS scores (r = 0.354, 0.414, 0.602, and 0.456, respectively). Independent influencing factors included disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and anxiety scores (P < 0.05). The areas under the curve for predicting social functional impairment using these factors were 0.713, 0.559, 0.684, 0.729, 0.668, and 0.628, respectively, with sensitivities of 79.2%, 61.8%, 76.8%, 81.7%, 63.6%, and 65.5% and specificities of 83.3%, 87.5%, 82.6%, 83.3%, 86.7%, and 92.1%, respectively.

The social function scores of patients with residual symptoms of depression are high. They are affected by disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and anxiety.

Core Tip: Depression with residual symptoms can progress to relapse, and patients often experience varying degrees of social function impairment. We analyzed the social function scores of patients with residual depression symptoms and their influencing factors. We proposed relevant theories of social function impairment in patients with residual symptoms of depression by observing the status quo of the social function score and mining the influencing factors. These theories have made significant contributions to the relevant research on residual social function impairment in depression.

- Citation: Liao ZL, Pu XL, Zheng ZY, Luo J. Social function scores and influencing factors in patients with residual depressive symptoms. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(1): 98630

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i1/98630.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i1.98630

Depression is a mental disease characterized by slow or reduced speech and movement, low emotion, and slow thinking, which brings great trouble to patients’ studies, work, and life and places a heavy burden on families and society[1]. The complete recovery from depression, recovery of social function, and improvement of quality of life are common wishes of patients, their families, and society. However, 20%-40% of patients who receive antidepressant therapy for 8-12 weeks during a depressive episode still have residual symptoms, which are highly likely to progress to the next recurrence of prodromal symptoms, even though their depressive symptoms are relieved and function is restored[2]. The residual symptoms of depression mainly include persistent depressive symptoms (such as depression, guilt, lack of motivation, mental impairment, and suicide attempts) and concomitant depressive symptoms (such as anxiety, fatigue, physical pain, cognitive impairment, and irritability). Studies have shown that patients with residual depression symptoms exhibit significantly reduced social function[3]. Social function refers to the ability, efficacy, and role of the body in various components of the social system, and its decline can lead to social dysfunction and social responsibility[4]. The reduced social function of patients with depression increases their suicidal tendency, which is related to poor social problem-solving ability, narrow social networks, and interpersonal relationship breakdown[5]. Currently, the factors that influence social functioning in patients with residual symptoms of depression are unclear. Therefore, we collected the social function scores of patients with residual depression symptoms. We determined the factors influencing social function to provide a reference for preventing social function impairment in patients with residual depression symptoms.

This research was an observational study, and a questionnaire survey was conducted with patients who had residual symptoms of depression and healthy patients undergoing physical examinations admitted to Affiliated Hospital of the Chongqing Population and Family Planning Research Institute from January 2022 to December 2023. Finally, 158 patients with residual symptoms of depression (case group) and 50 healthy individuals (control group) were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients diagnosed with depression based on the International Classification of Diseases (10th edition) criteria for depressive episodes (F32) or recurrent depressive disorder (F33)[6]; (2) Residual symptoms after 8-12 weeks of continuous treatment with antidepressants; (3) Age ≥ 18 years old; and (4) Volunteered to participate in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Pregnant or breastfeeding women; (2) Mental diseases other than depression; (3) Failure to accurately understand the content of the scale for any reason; and (4) Lack of clinical data. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital of the Chongqing Population and Family Planning Research Institute.

Patient data included sex, degree of depression, disease history, family history of depression, number of antidepressants used, use of antipsychotics, use of sedative and hypnotic drugs, medication compliance, therapy method, comorbidities, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, age, years of education, duration from illness onset to hospital visit, duration of depressive episodes, Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) score, Life Event Scale (LES) score, Family Assessment Device (FAD) score, anxiety score, and stigma at discharge.

Residual depressive symptoms were evaluated using the 16-item Self-Report Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-SR16) scale[7], which consists of 16 items, each scored from 0-3 points, with the total score ranging from 0-27 points. Higher scores indicate more serious depressive symptoms. After 8-12 weeks of drug treatment in the acute phase, patients with a total QIDS-SR16 score > 5 were assessed as having residual symptoms (6-10, mild residual symptoms; ≥ 11, significant residual symptoms; ≥ 1, single residual symptom).

The SSRS[8] was used to evaluate objective support and subjective feelings from social relationships with colleagues, friends, and family members. Items 2, 6, and 7 were objective support scores; items 1, 3, 4, and 5 were subjective support scores; and items 8-10 were support utilization scores. The total score of the three items was the SSRS score. The higher the score, the better the social support.

The LES[9] was used to assess the impact of the patients’ life events on individuals, including 48 Life events. The higher the score, the stronger the impact of life events and the psychological burden on patients. The family function of the patients was evaluated using the FAD[10], with a total of 60 items, each scored on a 4-point scale. The higher the total score, the better the family function.

Items 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale were used to evaluate the patients’ anxiety state. The score for each item was 0-3 with a total score of 0-21, with ≥ 8 indicating anxiety and ≥ 12 indicating significant clinical psychiatric symptoms[11].

The Stigma Assessment Scale (SAS)[12] measured stigma levels, comprising 32 questions about treatment, ability, and social factors. The scores for each question were 0 (no), 1 (rarely), 2 (sometimes), and 3 (often). Higher scores indicated higher stigma levels. The reliability and validity of the scale are good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.9).

Social functioning was assessed using the SDS[13]. The scale consists of three items: work/study, family, and social contact, with a score of 0-10 for each item. The SDS score is the sum of the above three items, with a score of 0-30. The higher the score, the more serious the impairment in social function. If the total score is < 6 and the sub-item score is ≤ 2, the social function is normal. Otherwise, the social function is impaired.

The degree of depression was assessed by a self-rating depression scale[14] that evaluated psychotic affective symptoms, somatic disorders, psychomotor disorders, and depressive psychological disorders in the depressive state. The scale contained 20 items. The total rough score is the sum of the scores for each item, and the standard score is the integer part of the value of 1.25 times the total rough score. Standard scores correspond to the following degrees of depression: 50-60, mild depression; 60-70, moderate depression; and ≥ 70, severe depression.

The conversion of medication compliance is as follows: “Stick to medication” was defined as the total number of days interrupted during treatment not exceeding 2 weeks, and intermittent medication use was defined as the total number of days interrupted treatment being 2 weeks or more.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-15[15] was used to evaluate physical symptoms. There are 15 items on the scale, each graded on a 3-point scale, with a total score of 0-30 points. Higher scores indicate more serious physical symptoms. The criteria for somatic symptoms were 0-4 as none, 5-9 as mild, 10-14 as moderate, and 15-30 as severe.

This study used logistic regression analysis, with the sample size calculated by the events per variable (EPV) method. According to previous studies, the incidence of social function impairment in patients with residual depressive symptoms ranges from 30%-70%. Assuming that the incidence of social function impairment in this study is 60%, it was expected that this study would include eight variables in the multivariate regression model. Taking EPV = 10, sample size was calculated as follows: Number of included variables × EPV / incidence rate = 8 × 10/60% = 133 cases. Considering a 10% dropout rate, this study required a sample size of 146 cases.

SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States) was used to analyze the data. Normally distributed data are expressed as mean ± SD and were analyzed using the two-sided independent-sample t-test. The non-parametric rank-sum test (Z) was used to test non-normally distributed data, and Spearman correlation was used to analyze the correlation. Multiple linear regression was used to analyze the factors influencing SDS scores in patients with residual depressive symptoms, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to analyze the predictive efficacy of influencing factors on social function impairment. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

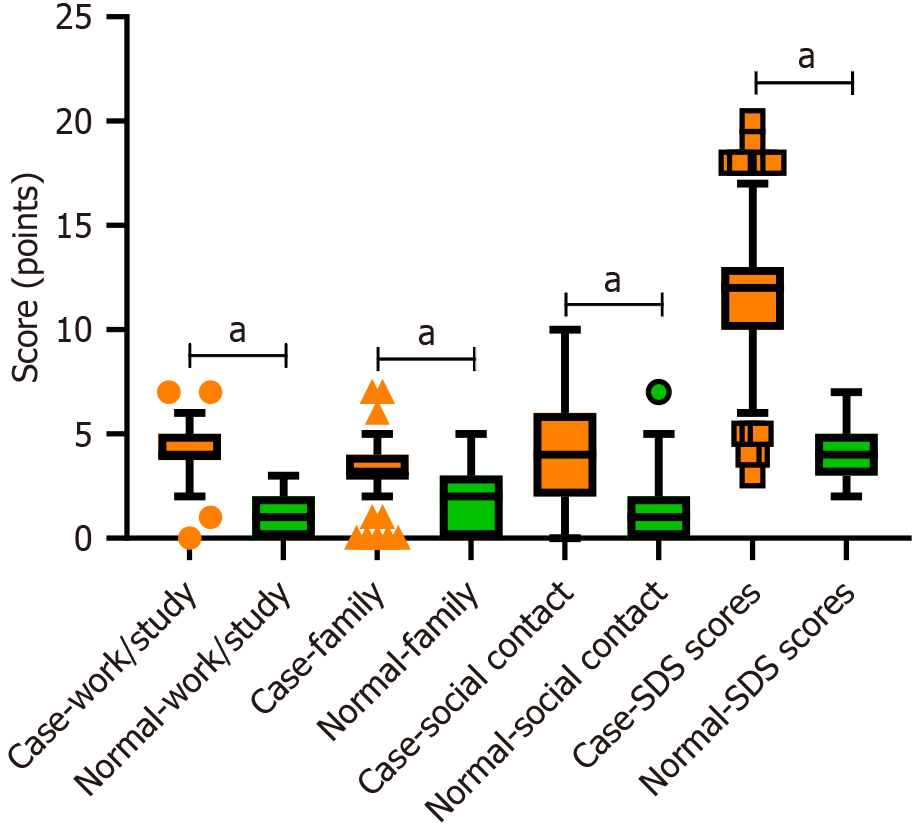

For the case group, the SDS scores for work/study, family, social contact, and SDS were 4.04 ± 1.12, 3.45 ± 1.23, 3.99 ± 2.63, and 11.48 ± 3.26, respectively. In the control group, the scores were 0.98 ± 0.93, 1.78 ± 1.50, 1.32 ± 1.63, and 4.08 ± 1.29, respectively. Compared to the control group, the SDS scores and other items in the case group were higher (P < 0.05; Figure 1).

There were no significant differences in the SDS scores for sex, degree of depression, family history of depression, number of antidepressants used, use of antipsychotics, use of sedative and hypnotic drugs, comorbidities, age, years of education, duration from illness onset to hospital visit, duration of depressive episode, SSRS score, LES score, FAD score, or SAS scores (all P > 0.05). SDS scores were higher in patients with relapse, discontinuous medication, drug therapy alone, severe somatic symptoms, obvious residual symptoms, and anxiety scores ≥ 8 (P < 0.05; Table 1).

| Data | Cases | SDS score (mean ± SD) | Z/t | P value |

| Sex | -0.537 | 0.591 | ||

| Male | 56 | 11.27 ± 3.37 | ||

| Female | 102 | 11.53 ± 3.33 | ||

| Degree of depression | 0.575 | 0.750 | ||

| Mild | 45 | 11.42 ± 3.86 | ||

| Moderate | 110 | 11.54 ± 3.07 | ||

| Severe | 3 | 13.00 ± 2.16 | ||

| Disease history | -4.432 | < 0.001 | ||

| First-episode | 67 | 10.03 ± 3.08 | ||

| Recurrence | 91 | 12.49 ± 2.88 | ||

| Family history of depression | 0.6901 | 0.491 | ||

| Yes | 33 | 11.15 ± 2.78 | ||

| No | 125 | 11.61 ± 3.39 | ||

| Family history of depression | -0.719 | 0.472 | ||

| 1 | 13 | 12.08 ± 2.53 | ||

| ≥ 2 | 145 | 11.49 ± 3.37 | ||

| Use of antipsychotics | -1.3891 | 0.167 | ||

| Yes | 31 | 12.23 ± 2.85 | ||

| No | 127 | 11.23 ± 3.26 | ||

| Use of sedative and hypnotic drugs | -1.121 | 0.262 | ||

| Yes | 6 | 13.00 ± 2.45 | ||

| No | 152 | 11.54 ± 3.20 | ||

| Medication compliance | -5.191 | < 0.001 | ||

| Stick to medication | 140 | 10.77 ± 2.81 | ||

| Intermittent medication use | 18 | 15.50 ± 2.36 | ||

| Therapy method | -7.546 | < 0.001 | ||

| Drug therapy alone | 56 | 14.02 ± 2.66 | ||

| Drugs and nursing intervention | 102 | 9.79 ± 2.60 | ||

| Comorbidities | -0.6371 | 0.525 | ||

| Yes | 19 | 11.95 ± 3.35 | ||

| No | 139 | 11.50 ± 3.38 | ||

| Degree of somatic symptoms | 48.032 | < 0.001 | ||

| None | 48 | 9.35 ± 2.71 | ||

| Mild | 36 | 11.97 ± 3.39 | ||

| Moderate | 49 | 12.08 ± 2.83 | ||

| Severe | 25 | 13.80 ± 2.24 | ||

| Residual symptoms | -5.710 | < 0.001 | ||

| Slight | 107 | 10.46 ± 3.37 | ||

| Obvious | 51 | 13.51 ± 2.46 | ||

| Age | -0.584 | 0.559 | ||

| < 40 years | 70 | 11.56 ± 3.24 | ||

| ≥ 40 years | 88 | 11.36 ± 3.38 | ||

| Years of education | -0.072 | 0.943 | ||

| < 12 years | 80 | 11.36 ± 3.25 | ||

| ≥ 12 years | 78 | 11.56 ± 3.37 | ||

| Duration from illness onset to hospital visit | -0.300 | 0.943 | ||

| < 3 years | 26 | 11.62 ± 3.05 | ||

| ≥ 3 years | 132 | 11.39 ± 3.31 | ||

| Duration of depressive episode | -1.149 | 0.251 | ||

| < 16 weeks | 80 | 10.83 ± 3.00 | ||

| ≥ 16 weeks | 78 | 11.91 ± 3.41 | ||

| SSRS score | -0.219 | 0.827 | ||

| < 28 | 68 | 11.60 ± 3.59 | ||

| ≥ 28 | 90 | 11.20 ± 3.00 | ||

| LES score | -1.429 | 0.153 | ||

| < 42 | 78 | 11.80 ± 3.21 | ||

| ≥ 42 | 80 | 11.14 ± 3.34 | ||

| FAD score | -1.735 | 0.083 | ||

| < 138 | 78 | 10.97 ± 3.35 | ||

| ≥ 138 | 80 | 11.94 ± 3.20 | ||

| Anxiety score | -2.353 | 0.019 | ||

| < 8 | 74 | 10.86 ± 2.77 | ||

| ≥ 8 | 84 | 11.86 ± 3.57 | ||

| Stigma at discharge score | -1.0181 | 0.310 | ||

| < 75 | 65 | 11.18 ± 3.19 | ||

| ≥ 75 | 93 | 11.51 ± 3.90 |

Among patients with residual depressive symptoms, disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, and residual symptoms were positively correlated with the SDS score (r = 0.354, 0.414, 0.602, and 0.456, respectively; all P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Indexes | Assignment | Correlation with SDS score | |

| r value | P value | ||

| Disease history | 0 = first-episode; 1 = recurrence | 0.354 | < 0.001 |

| Medication compliance | 0 = stick to medication; 1 = intermittent medication use | 0.414 | < 0.001 |

| Therapy method | 0 = drug therapy alone; 1 = drugs and nursing intervention | 0.602 | < 0.001 |

| Degree of somatic symptoms | 0 = none; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe | 0.200 | 0.012 |

| Residual symptoms | 0 = slight; 1 = obvious | 0.456 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety score | Actual value | 0.270 | 0.001 |

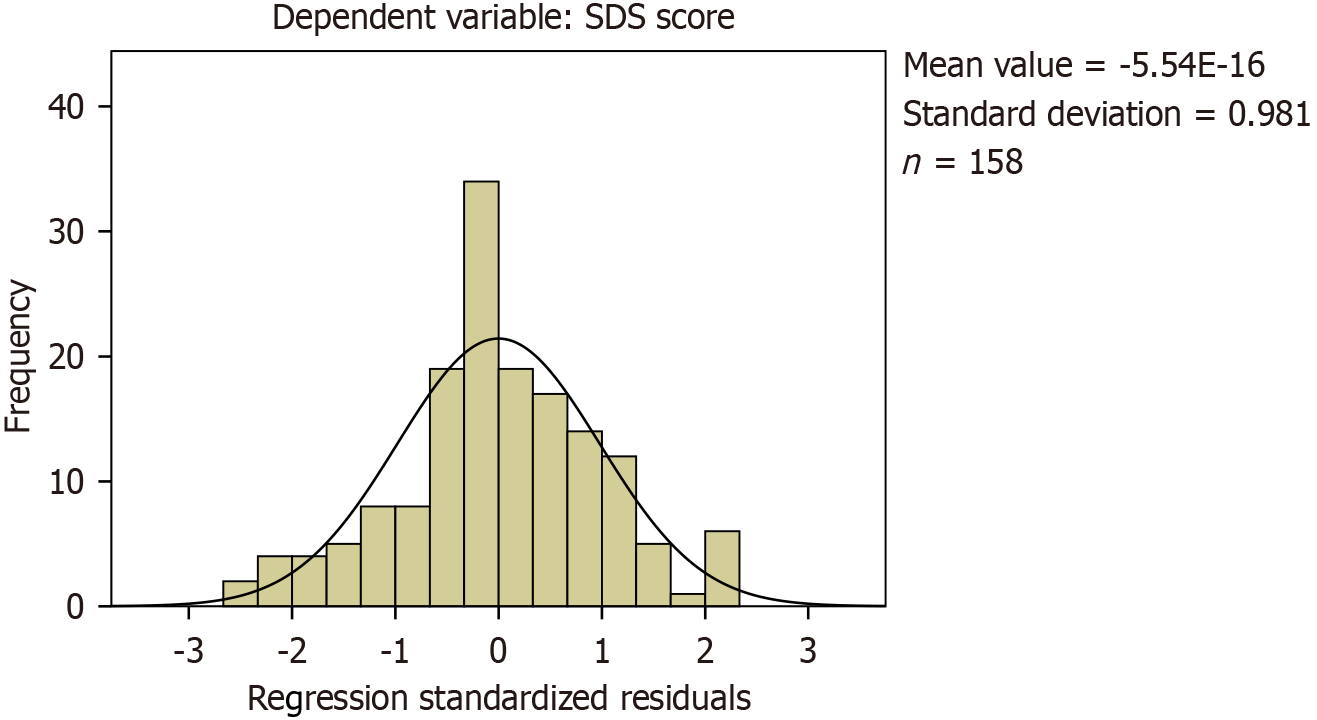

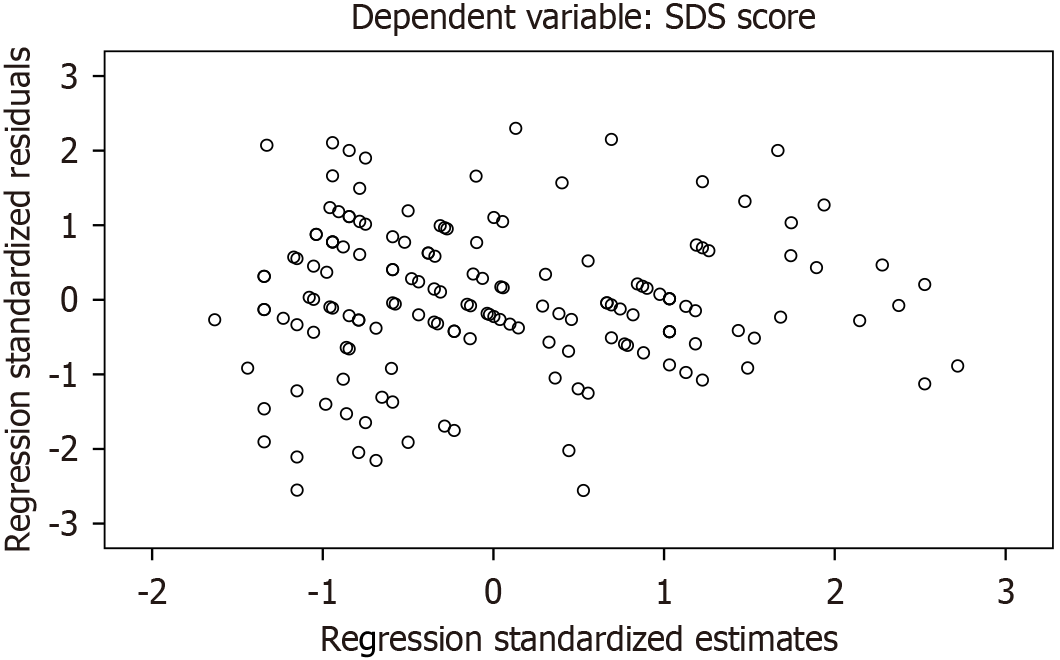

SDS scores of patients with residual depressive symptoms were used as dependent variables and disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and anxiety scores were used as independent variables in multiple linear regression analysis. Disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and anxiety scores were independent influencing factors for the SDS score of patients with residual depressive symptoms (P < 0.05; Table 3, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

| Variable | β | SE | β′ | t value | P value |

| Constant | 6.908 | 0.756 | - | 9.140 | < 0.001 |

| Disease history | 1.337 | 0.393 | 0.204 | 3.405 | 0.001 |

| Medication compliance | 2.748 | 0.594 | 0.269 | 4.624 | < 0.001 |

| Therapy method | 2.237 | 0.431 | 0.330 | 5.195 | < 0.001 |

| Degree of somatic symptoms | 0.364 | 0.172 | 0.120 | 2.113 | 0.036 |

| Residual symptoms | 1.505 | 0.419 | 0.217 | 3.594 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety score | 0.230 | 0.093 | 0.142 | 2.480 | 0.014 |

The model was shown to have a good fit (r = 0.734) with a linear correlation (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Model summary | ANOVA for SDS scores | ||||||

| R | R2 | Adjustment R2 | Quadratic sum | Mean square | F value | P value | |

| Model summary value | 0.734 | 0.539 | 0.520 | - | - | - | - |

| Regression | - | - | - | 896.064 | 149.344 | 29.385 | < 0.001 |

| Residual error | - | - | - | 767.436 | 5.082 | - | - |

| Total | - | - | - | 1663.500 | - | - | - |

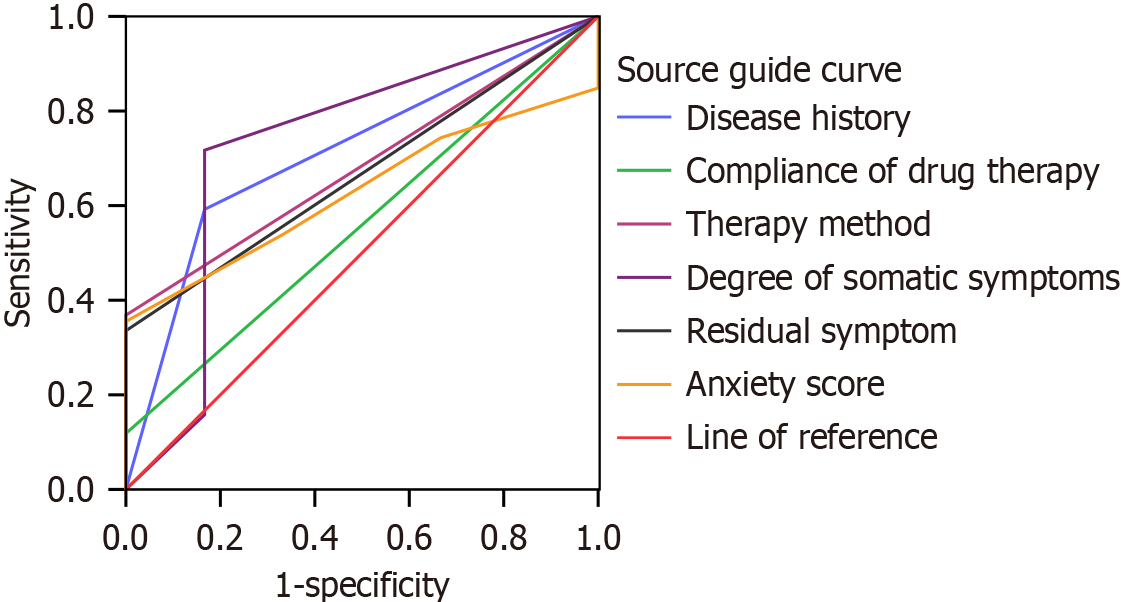

Among the 158 patients with residual depressive symptoms, 152 had varying degrees of social functional impairment. ROC curves were used to analyze the above indicators to predict social function impairment. The areas under the curve (AUCs) of disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and anxiety scores in predicting social functional impairment in patients with residual depressive symptoms were 0.713, 0.559, 0.684, 0.729, 0.668, and 0.628, respectively, with sensitivities of 79.2%, 61.8%, 76.8%, 81.7%, 63.6%, and 65.5% and specificities of 83.3%, 87.5%, 82.6%, 83.3%, 86.7%, and 92.1%, respectively. The optimal cutoff for the anxiety score was 8.5 (Table 5, Figure 4).

| Test result variable | AUC (95%CI) | SE | P value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Optimum cutoff value |

| Disease history | 0.713 (0.525–0.900) | 0.096 | 0.012 | 79.2 | 83.3 | - |

| Medication compliance | 0.559 (0.349–0.770) | 0.107 | 0.040 | 61.8 | 87.5 | - |

| Therapy method | 0.684 (0.528–0.840) | 0.080 | 0.026 | 76.8 | 82.6 | - |

| Degree of somatic symptoms | 0.729 (0.485–0.972) | 0.124 | 0.008 | 81.7 | 83.3 | - |

| Residual symptoms | 0.668 (0.504–0.831) | 0.083 | 0.034 | 63.6 | 86.7 | - |

| Anxiety score | 0.628 (0.492–0.764) | 0.069 | 0.037 | 65.5 | 92.1 | 8.5 |

The impairment of social function in patients with residual symptoms of depression increases the difficulty of treatment and also increases the burden on patients, their families, and society. The ultimate goal of clinicians is to expedite patient recovery, facilitate their return to their families, and restore their social functioning. Currently, because the mechanism of social function impairment in patients with residual depressive symptoms is undefined, research on the factors influencing social function is of great significance for their treatment and prognosis.

The results of this study showed that there were significant differences in SDS scores among patients with different disease histories; medication compliance, therapy methods, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and the patient’s disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, and residual symptoms positively correlated with SDS scores. Multiple linear regression analysis of the above variables revealed that disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and anxiety scores were independent factors affecting the SDS scores of patients with residual symptoms of depression. Compared with patients with first-episode depression, those with recurrent depression had higher SDS scores. This may be because repeated episodes of depression, especially during acute episodes, repeatedly reduce patients’ ability to process information centrally and reduce cognitive function, thus weakening patients’ ability to adapt to society[16]. There is also evidence that cognitive impairment occurs during the first episode of depression, and individuals with multiple episodes show worse cognitive impairment than indivi

This study demonstrated that combining drug therapy with nursing intervention was protective against increased SDS scores in patients. According to these data, in addition to simple drug treatments, reasonable nursing interventions have a positive effect on the prognosis of patients with depression. Nursing interventions are patient-centered and integrate personalized psychological, life, and environmental nursing measures. Moreover, they focus on strengthening emotional support from family and society, gradually eliminating negative behaviors such as loss, anger, and autism with correct communication and guidance. This approach helps patients establish confidence in confronting and managing their condition, thereby promoting the patient’s mental state from negative to positive. Participation in social activities in a positive mood reduced SDS scores. However, life and environmental factors can promote the development of social functions, self-image improvement, self-confidence enhancement, and treatment abandonment. Patients can thus access and play their roles within the social system and eventually reintegrate into society[21,22].

The results of our data analysis showed that the more severe the degree of physical symptoms, the higher the SDS score. One possible explanation is that the physical symptoms of patients with depression often involve neurological, digestive, cardiovascular, respiratory, and urinary system symptoms[23,24]. The duration of residual symptoms of depression can be prolonged or even chronic, resulting in weakened social function and increased SDS scores. Zhang et al[25] reported that neuropsychiatric symptoms aggravate cognitive impairment in patients with depression. According to Rhebergen et al[26], psychopathology has long-term debilitating effects. Long-term persistent exponential symptoms are associated with impaired function, and patients with major depressive disorder show slower and poorer functional recovery. Relevant studies have also shown that the more physical symptoms patients with impaired social function have, the less satisfied they are with their quality of life and the weaker their social function[3]. Therefore, we suggest that clinical attention should be paid to the residual symptoms of patients with depression, and corresponding interventions should be carried out to reduce the damage to patients’ social functioning and gradually restore it. In patients with residual symptoms of depression and anxiety disorder, the nervous system is more sensitive. The emotional brain is abnormally active, and the amygdala experiences unexpected stimulation, which leads to the forced triggering of the safety defense mechanism[27]. Patients are overly restrained by security defense mechanisms, which make it difficult for them to concentrate on studying and working. In addition, patient anxiety mainly comes from excessive worry about physical diseases, which leads to increased sensitivity to disease discomfort and reduced self-care ability. Low concentration and self-care ability can weaken the defense ability of patients to cope with social stress events, leading to negative self-evaluation, low self-esteem, widespread despair, and other negative psychological symptoms, resulting in social dysfunction and increasing the SDS score. Liu et al[28] showed that anxiety symptoms are risk factors for social functional impairment in patients with depression, which is similar to the results of this study. Our research team demonstrated increased social functioning scores in patients with residual depressive symptoms and explored the influencing factors and possible mechanisms. However, this study has limitations. Due to missing data and conditional restrictions, we were unable to implement a longitudinal approach to observe changes in social function over time and the long-term effects of various factors. Therefore, more comprehensive studies are needed to deeply explore the changes in social function scores of patients with residual depressive symptoms.

In summary, the social function score of patients with residual depressive symptoms was higher than that of healthy adults. Social function was affected by disease history, medication compliance, therapy method, degree of somatic symptoms, residual symptoms, and anxiety. Clinical intervention measures should be taken according to the above factors to reduce the social function score and occurrence of social function impairment and avoid adverse outcomes.

| 1. | Greenberg P, Chitnis A, Louie D, Suthoff E, Chen SY, Maitland J, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Fournier AA, Kessler RC. The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2019). Adv Ther. 2023;40:4460-4479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhou J, Zhou J, Feng Z, Feng L, Xiao L, Chen X, Yang J, Feng Y, Wang G. Identifying the core residual symptom in patients with major depressive disorder using network analysis and illustrating its association with prognosis: A study based on the national cohorts in China. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2024;87:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Y, Wang G, Zhang N, Huang J, Wu W, Jia F, Liu T, Gao C, Hu J, Hong W, Fang Y. Association between residual symptoms and social functioning in patients with depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;98:152164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zu S, Wang D, Fang J, Xiao L, Zhu X, Wu W, Wang G, Hu Y. Comparison of Residual Depressive Symptoms, Functioning, and Quality of Life Between Patients with Recurrent Depression and First Episode Depression After Acute Treatment in China. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:3039-3051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Szanto K, Dombrovski AY, Sahakian BJ, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, Reynolds CF 3rd, Clark L. Social emotion recognition, social functioning, and attempted suicide in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:257-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bhatia MS, Gautam P, Jhanjee A. Psychiatric Morbidity in Patients with Chikungunya Fever: First Report from India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:VC01-VC03. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bandinelli L, Schäfer JL, Kluwe-Schiavon B, Grassi-Oliveira R. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and Self-Report (QIDS-SR16) for the Brazilian population. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2023;45:e20200378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fang XH, Wu Q, Tao SS, Xu ZW, Zou YF, Ma DC, Pan HF, Hu WB. Social Support and Depression Among Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients in Anhui, China. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:595-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xu Z, Chen Z, Shen T, Chen L, Tan T, Gao C, Chen B, Yuan Y, Zhang Z. The impact of HTR1A and HTR1B methylation combined with stress/genotype on early antidepressant efficacy. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;76:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Caño González A, Rodríguez-Naranjo C. The McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) dimensions involved in the prediction of adolescent depressive symptoms and their mediating role in regard to socioeconomic status. Fam Process. 2024;63:414-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Garaiman A, Mihai C, Dobrota R, Jordan S, Maurer B, Flemming J, Distler O, Becker MO. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with systemic sclerosis: a psychometric and factor analysis in a monocentric cohort. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39 Suppl 131:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang F, Yang BX, Stone TE, Wang XQ, Zhou Y, Zhang J, Jiao SF. Stigma towards depression in a community-based sample in China. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;97:152152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abdin E, Seet V, Jeyagurunathan A, Tan SC, Mohmad Khalid MIS, Mok YM, Verma S, Subramaniam M. Equipercentile linking of the Sheehan Disability Scale and the World Health Organization Assessment Schedule 2.0 scales in people with mental disorders. J Affect Disord. 2024;350:539-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cheng L, Gao W, Xu Y, Yu Z, Wang W, Zhou J, Zang Y. Anxiety and depression in rheumatoid arthritis patients: prevalence, risk factors and consistency between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Zung's Self-rating Anxiety Scale/Depression Scale. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2023;7:rkad100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gavurova B, Ivankova V, Rigelsky M, Mudarri T, Miovsky M. Somatic Symptoms, Anxiety, and Depression Among College Students in the Czech Republic and Slovakia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:859107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Batinic B, Djokic V, Ivkovic M. Assessment of Cognitive Function, Social Disability and Basic Life Skills in Euthymic Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Psychiatr Danub. 2021;33:320-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Varghese S, Frey BN, Schneider MA, Kapczinski F, de Azevedo Cardoso T. Functional and cognitive impairment in the first episode of depression: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145:156-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Srithumsuk W, Chaleoykitti S, Jaipong S, Pattayakorn P, Podimuang K. Association between depression and medication adherence in stroke survivor older adults. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2021;18:e12434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chawa MS, Yeh HH, Gautam M, Thakrar A, Akinyemi EO, Ahmedani BK. The Impact of Socioeconomic Status, Race/Ethnicity, and Patient Perceptions on Medication Adherence in Depression Treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kato M, Hori H, Inoue T, Iga J, Iwata M, Inagaki T, Shinohara K, Imai H, Murata A, Mishima K, Tajika A. Discontinuation of antidepressants after remission with antidepressant medication in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:118-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Christie L, Inman J, Davys D, Cook PA. A systematic review into the effectiveness of occupational therapy for improving function and participation in activities of everyday life in adults with a diagnosis of depression. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:962-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang Z, Deng S, Lv H, Fan Y, Zhang L, Wang F. Effect of WeChat-based continuous care intervention on the somatic function, depression, anxiety, social function and cognitive function for cancer patients: Meta-analysis of 18 RCTs. Nurs Open. 2023;10:6045-6057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Siddiqui NY, Wiseman JB, Cella D, Bradley CS, Lai HH, Helmuth ME, Smith AR, Griffith JW, Amundsen CL, Kenton KS, Clemens JQ, Kreder KJ, Merion RM, Kirkali Z, Kusek JW, Cameron AP; LURN. Mental Health, Sleep and Physical Function in Treatment Seeking Women with Urinary Incontinence. J Urol. 2018;200:848-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Glaser AP, Mansfield S, Smith AR, Helfand BT, Lai HH, Sarma A, Yang CC, Taddeo M, Clemens JQ, Cameron AP, Flynn KE, Andreev V, Fraser MO, Erickson BA, Kirkali Z, Griffith JW; LURN Study Group. Impact of Sleep Disturbance, Physical Function, Depression and Anxiety on Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Results from the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN). J Urol. 2022;208:155-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang M, Chen B, Zhong X, Zhou H, Wang Q, Mai N, Wu Z, Chen X, Peng Q, Zhang S, Yang M, Lin G, Ning Y. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Exacerbate the Cognitive Impairments in Patients With Late-Life Depression. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:757003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rhebergen D, Beekman AT, de Graaf R, Nolen WA, Spijker J, Hoogendijk WJ, Penninx BW. Trajectories of recovery of social and physical functioning in major depression, dysthymic disorder and double depression: a 3-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2010;124:148-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Piperoglou M, Hopwood M, Norman TR. Adjunctive Docosahexaenoic Acid in Residual Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2023;43:493-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu W, Zhou Y, Zheng W, Wang C, Zhan Y, Li H, Chen L, Zhao C, Ning Y. Mediating effect of neurocognition between severity of symptoms and social-occupational function in anxious depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:667-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |