Published online Jul 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i7.1017

Revised: May 9, 2024

Accepted: June 13, 2024

Published online: July 19, 2024

Processing time: 112 Days and 17.1 Hours

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a rapidly growing malignant tumor, and chemotherapy is one of the treatments used to combat it. Although advance

To explore the factors related to CRF, anxiety, depression, and mindfulness levels in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy.

General information was collected from the electronic medical records of eligible patients. Sleep quality and mindfulness level scores in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy were evaluated by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form. The Piper Fatigue Scale was used to evaluate the CRF status. The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and Self-Rating Depression Scale were used to evaluate anxiety and depression status. Univariate analysis and multivariate regression analysis were used to investigate the factors related to CRF.

The overall average CRF level in 62 patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy was 5.74 ± 2.51. In 25 patients, the highest rate of mild fatigue was in the cognitive dimension (40.32%), and in 35 patients the highest moderate fatigue rate in the behavioral dimension (56.45%). In the emotional dimension, severe fatigue had the highest rate of occurrence, 34 cases or 29.03%. The CRF score was positively correlated with cancer experience (all P < 0.01) and negatively correlated with cancer treatment efficacy (all P < 0.01). Tumor staging, chemotherapy cycle, self-efficacy level, and anxiety and depression level were related to CRF in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy.

There was a significant correlation between CRF and perceptual control level in patients. Tumor staging, chemotherapy cycle, self-efficacy level, and anxiety and depression level influenced CRF in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy.

Core Tip: The study aimed to explore the factors related to cancer-related fatigue (CRF), anxiety, depression, and mindfulness level in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) during chemotherapy. Univariate analysis and multivariate regression analysis were used to investigate the related factors of CRF. The overall average level of CRF in 62 patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy was 5.74 ± 2.51. There was a significant correlation between CRF and perceptual control level in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy. Tumor staging, chemotherapy cycle, self-efficacy level, and anxiety and depression level influenced CRF in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy.

- Citation: Hao XQ, Yang XD, Qi Y. Identifying relevant factors influencing cancer-related fatigue in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma during chemotherapy. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(7): 1017-1026

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i7/1017.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i7.1017

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). DLBCL is characterized by progressive destruction of lymphoid structures or diffuse infiltration of large B lymphoid cells[1]. It is the most common NHL in adults, accounting for 30%-40% of all new cases. The cause of the disease is related to genes, the environment, viruses, and the aging population[2]. In 2020, 544352 new cases of NHL were reported worldwide, which ranked it as the 13th most common malignant tumor[3]. The incidence of DLBCL has increased worldwide in recent decades, including in China[4].

The molecular genetics and immunophenotype of DLBCL are highly heterogeneous, and chemotherapy is the primary clinical treatment[5]. However, the prolonged treatment cycle, high cost, and frequent adverse reactions associated with chemotherapy, along with patient concerns related to illness, can lead to prolonged periods of anxiety and depression. Cancer symptoms and the side effects of chemotherapy drugs make patients prone to negative emotions, fatigue, and other adverse reactions[6]. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is a common symptom in patients with DLBCL[7]. It is complex, and if severe it may affect quality of life, activities of daily life, and ultimately, survival. Fatigue is seldom an isolated condition and is typically accompanied by sleep disorders, unhealthy sleeping habits, emotional conditions (like depression and anxiety), or pain[8]. CRF usually lasts for a long time. It may begin at diagnosis and continue until several years after the end of treatment[9]. CRF and emotional disorders may be more uncomfortable for patients than symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and pain, which can be controlled by drugs[10]. Continuous CRF and emotional disorders not only affect quality of life and lead to delay or termination of antitumor therapy but also make patients unable to return to work and a normal life after curative treatment[11]. These destructive emotions seriously impact the effectiveness of treatment and quality of life and place a heavy burden on the patient’s family. Thus, it is important to identify the variables that impact CRF, anxiety, and depression in DLBCL patients undergoing chemotherapy, from a clinical standpoint. That was the aim of this study.

We evaluated the data of 62 patients who were. diagnosed with DLBCL and admitted to the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University between January 2020 and December 2022. The Ethics Committee of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University approved the study (No. 2020ky022) and it was performed following the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed a written informed consent form.

Eligible patients were ≥ 20 years of age with DLBCL and symptoms of CRF and emotional disorders. All had been treated with similar chemotherapy regimens. Patients with any of the following were excluded: (1) Functional injuries of the heart, liver, lung, and other organs; (2) A previous history of mental illness or mental disorders; (3) Cognitive impairment; or (4) Incomplete clinical records or lack of follow-up.

The clinical data of eligible patients, including sex, age, marital status, education level, disease diagnosis, tumor type, chemotherapy cycle, and family history, among others, were collected from their electronic medical records. During the course of radiotherapy, nursing staff evaluated the patient's fatigue and psychological state.

The CRF status of the patients was evaluated with the Chinese edition of the Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS)[12]. The PFS is a subjective self-evaluation scale of perceived fatigue. It comprises 27 items across four behavioral dimensions, namely behavioral (six items), emotional (five items), cognitive (six items), and perceptual (five items). Each item uses a 0-10 score scale. The score for each item represents the severity of fatigue, 0-3 for no or mild fatigue, 3-6 for moderate fatigue, and 6-10 for severe fatigue.

The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)[13] were used to evaluate the anxiety and depression status of patients. The SDS scale includes 20 items related to depression, with a score of 1-4 for each item. The higher the score, the more serious the item. The total score multiplied by 1.25 is converted into a percentile, and a total score > 53 indicated depression. The SAS scale includes 20 anxiety-related items, scoring 1-4 for each item. The higher the score, the more serious the item. The total score multiplied by 1.25 was converted into a percentile, and a total score > 50 indicated anxiety.

The Chinese edition of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF)[14] was used to assess the mindfulness awareness level, which encompasses awareness, description, conscious action, nonjudgment, and nonreaction. Each dimension contains four items, each was scored from 1-5 points, and the total score is 20-100 points. The higher the score, the higher the level of mindfulness awareness. Sleep quality was evaluated by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[15]. The total PSQI score ranges from 0-21. The higher the score, the worse the sleep quality.

The Chinese version of the cancer experience and efficacy scale (CEES)[16] was used to evaluate the perceptual control ability of patients. The scale consists of two subscales, experience and efficacy, and each subscale includes three dimensions. The experience subscale is divided into personal experience (4 items), social experience (6 items), and emotional experience (6 items). The efficacy subscale is divided into individual efficacy (5 items), collective efficacy (5 items), and medical effectiveness (3 items). A total of 29 items are scored on a Likert scale, with responses ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree" with corresponding scores of 0 to 5. A high experience score indicates a more significant negative cancer experience. A high efficacy score indicates more effective dealing with cancer.

Continuous variables were reported as means ± SD or medians and interquartile range. Between-group differences were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are reported as n (%) and were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Cox regression analysis was used to analyze the factors related to CRF in patients with NHL. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

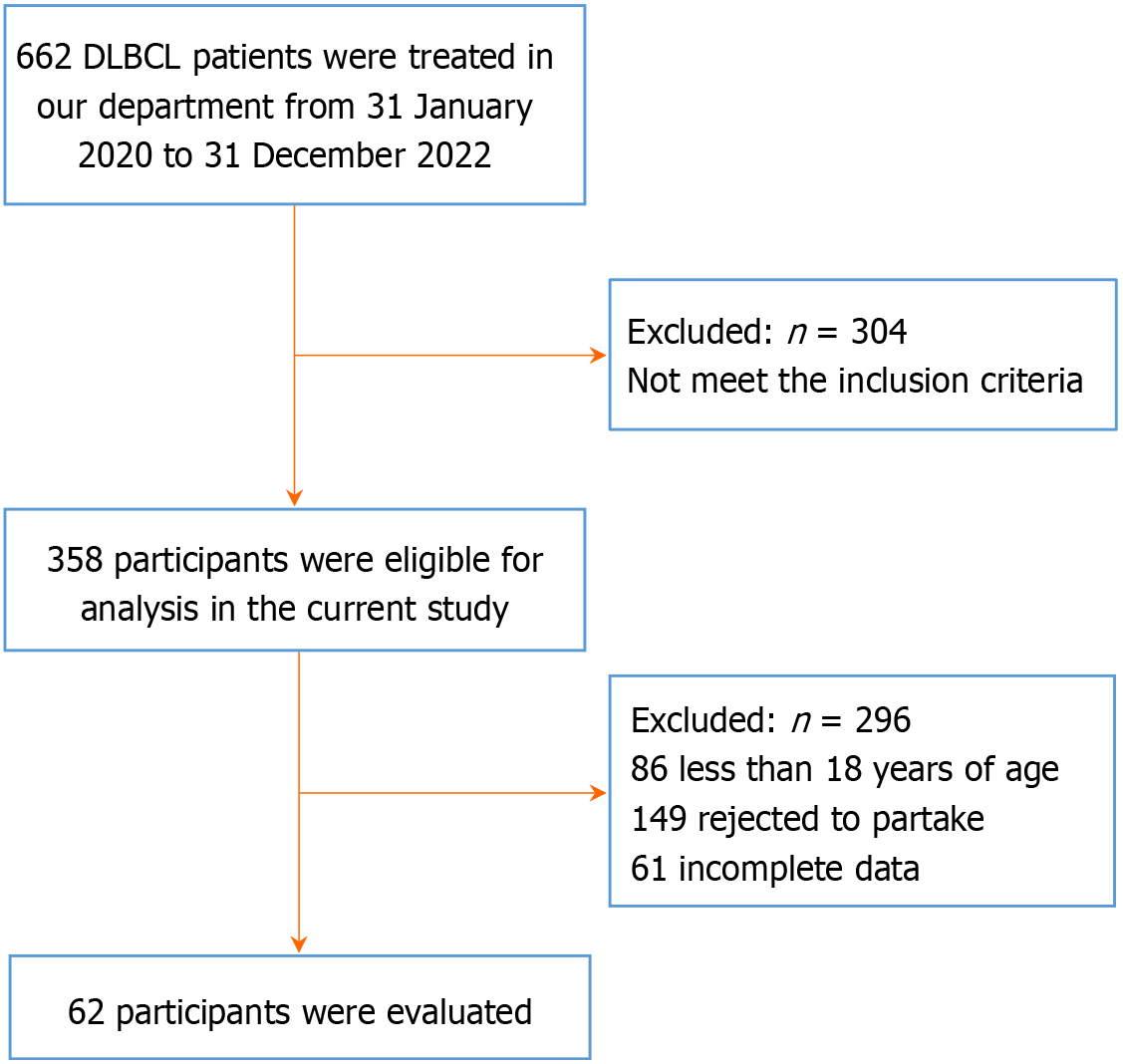

Between January 2020 and December 2022, 662 DLBCL patients were treated in our department, and 304 were not enrolled because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of those, 86 were less than 18 years of age; 149 were excluded because they refused to participate, and 61 were excluded because of incomplete data. The remaining 62 participants were eligible and were included in the study analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteri

| Characteristics | Eligible, n = 62 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 29 |

| Female | 33 |

| Age in years | |

| ≤ 65 | 49 |

| > 65 | 13 |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 23 |

| College | 20 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 |

| Graduate degree | 4 |

| ECOG performance status | |

| < 2 | 8 |

| ≥ 2 | 7 |

| BMI in kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25.4 (22.2-28.7) |

| High serum LDH | 9 |

| High serum β2m | 11 |

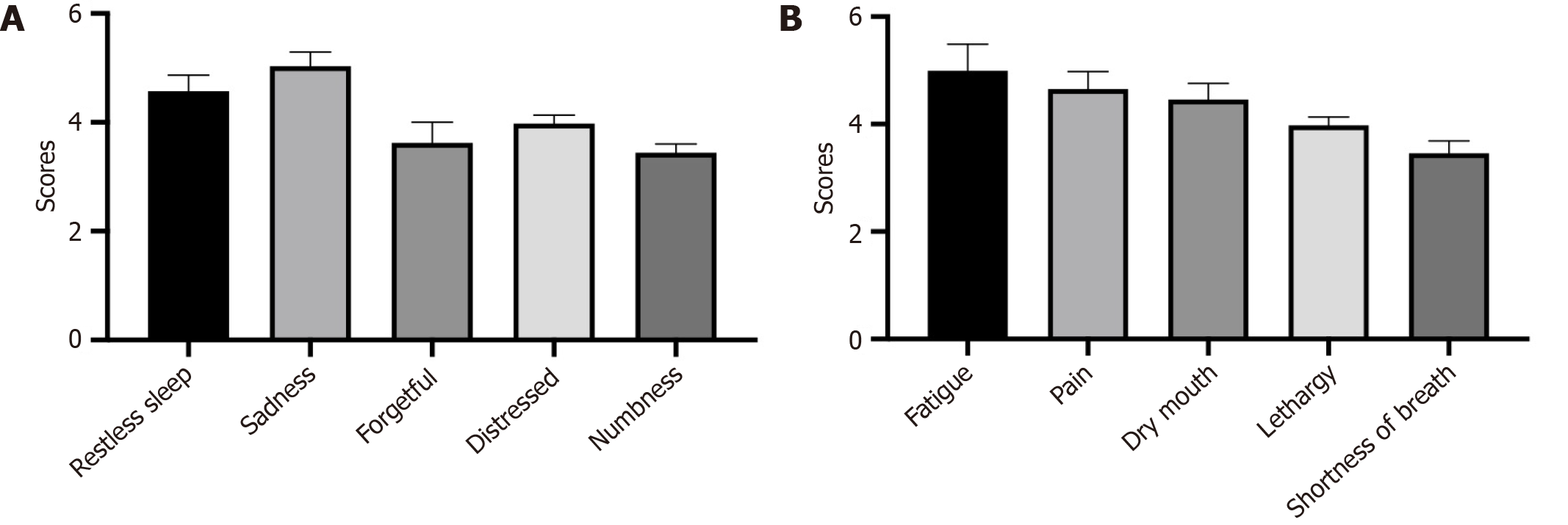

As shown in Table 2, the incidence of psychological symptoms in the 62 patients during chemotherapy was the highest for restless sleep (93.55%), followed by sadness (91.94%), forgetfulness (80.65%), distress (93.55%), and numbness (48.39%). The psychological symptom scores are shown in Figure 2A.

| Item | Eligible, n = 62 | Score |

| Restless sleep | 58 (93.55) | 4.51 ± 1.38 |

| Sadness | 57 (91.94) | 4.77 ± 1.40 |

| Forgetfulness | 50 (80.65) | 3.48 ± 1.12 |

| Distress | 58 (93.55) | 4.53 ± 1.37 |

| Numbness | 30 (48.39) | 3.47 ± 1.08 |

The sleep quality and mindfulness level scores during chemotherapy were evaluated by the PSQI and FFMQ-SF. The results are shown in Table 3.

| Assessment measure | Scores |

| PSQI | 10.49 ± 1.28 |

| FFMQ-SF | 49.85 ± 10.67 |

The CRF status of these 62 patients with DLBCL was investigated based on data from their electronic medical records (Table 4). The results showed that during chemotherapy the overall average CRF was 5.74 ± 2.51. In 25 patients (40.32%) the highest rate of mild fatigue was in the cognitive dimension, in 35 patients (56.45%). the highest rate of moderate fatigue was in the behavioral dimension, and in 34 patients (29.03%) the highest rate of severe fatigue was in the emotional dimension.

| Dimension | Average score | Mild fatigue, n (%) | Moderate fatigue, n (%) | Severe fatigue, n (%) |

| Behavior fatigue | 6.57 ± 2.43 | 18 (29.03) | 35 (56.45) | 9 (14.52) |

| Emotional fatigue | 5.25 ± 2.14 | 15 (24.19) | 29 (46.78) | 34 (29.03) |

| Perceived fatigue | 6.39 ± 2.36 | 20 (32.26) | 32 (51.61) | 10 (16.13) |

| Cognitive fatigue | 5.37 ± 2.48 | 25 (40.32) | 21 (33.87) | 16 (25.81) |

| Total CRF score | 5.74 ± 2.51 | 24 (38.71) | 26 (41.94) | 12 (19.35) |

Univariate analysis was conducted to evaluate the factors related to CRF in patients with DLBCL. The results showed that pain, tumor stage, degree of anxiety and depression, chemotherapy cycle, and self-efficacy affected CRF in these patients during chemotherapy (all P < 0.05, Table 5).

| Influencing factors | Eligible, n = 62 | Average PFS score | P value |

| Sex | 0.543 | ||

| Male | 29 | 5.44 ± 2.32 | |

| Female | 33 | 5.74 ± 2.20 | |

| Age in years | 0.095 | ||

| ≤ 65 | 49 | 4.59 ± 1.25 | |

| > 65 | 13 | 5.15 ± 2.42 | |

| Marital status | 0.206 | ||

| Married | 21 | 5.57 ± 2.34 | |

| Unmarried | 40 | 5.95 ± 2.53 | |

| Others | 1 | 6.54 ± 2.32 | |

| Education | 0.390 | ||

| High school or less | 23 | 4.39 ± 1.60 | |

| College | 20 | 4.37 ± 1.38 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 | 5.07 ± 2.21 | |

| Graduate degree | 4 | 5.93 ± 2.52 | |

| Self-efficacy level | 26 | 0.031 | |

| High | 26 | 4.66 ± 1.71 | |

| Medium | 9 | 5.56 ± 2.30 | |

| Low | 5.90 ± 2.51 | ||

| Anxiety and depression degree | 0.033 | ||

| Mild | 20 | 4.72 ± 1.32 | |

| Moderate | 29 | 5.50 ± 2.53 | |

| Severe | 13 | 5.97 ± 2.85 | |

| Tumor staging | 0.001 | ||

| Stage I | 25 | 4.34 ± 1.55 | |

| Stage II | 14 | 5.64 ± 2.19 | |

| Stage III | 13 | 5.82 ± 2.44 | |

| Stage IV | 10 | 6.78 ± 3.13 | |

| Chemotherapy cycle | 0.006 | ||

| First cycle | 23 | 4.09 ± 1.13 | |

| Second cycle | 19 | 4.52 ± 1.40 | |

| Third cycle | 11 | 5.72 ± 2.37 | |

| Fourth cycle | 9 | 6.46 ± 3.50 | |

| Pain degree | 0.004 | ||

| Mild | 15 | 4.54 ± 1.75 | |

| Moderate | 37 | 5.48 ± 2.44 | |

| Severe | 10 | 6.31 ± 3.47 |

As shown in Table 6, the incidence of CRF-related symptoms in these 62 patients was fatigue (95.16%), pain (82.26%), dry mouth (88.71%), lethargy (87.10%), and shortness of breath (45.16%). The symptom scores are shown in Figure 2B.

| Items | Eligible, n = 62 | Score |

| Fatigue | 59 (95.16) | 4.48 ± 1.47 |

| Pain | 51 (82.26) | 4.42 ± 1.48 |

| Dry mouth | 55 (88.71) | 4.35 ± 1.32 |

| Lethargy | 54 (87.10) | 4.08 ± 1.34 |

| Shortness of breath | 28 (45.16) | 3.52 ± 1.16 |

The perceptual control scores of the 62 study patients are shown in Table 7.

| Items | Score |

| Cancer experience | |

| Personal experience | 13.71 ± 1.98 |

| Social experience | 24.01 ± 3.02 |

| Emotional experience | 21.51 ± 3.12 |

| Cancer efficacy | |

| Personal efficacy | 15.71 ± 4.66 |

| Collective efficacy | 18.28 ± 4.72 |

| Medical care efficacy | 11.63 ± 2.03 |

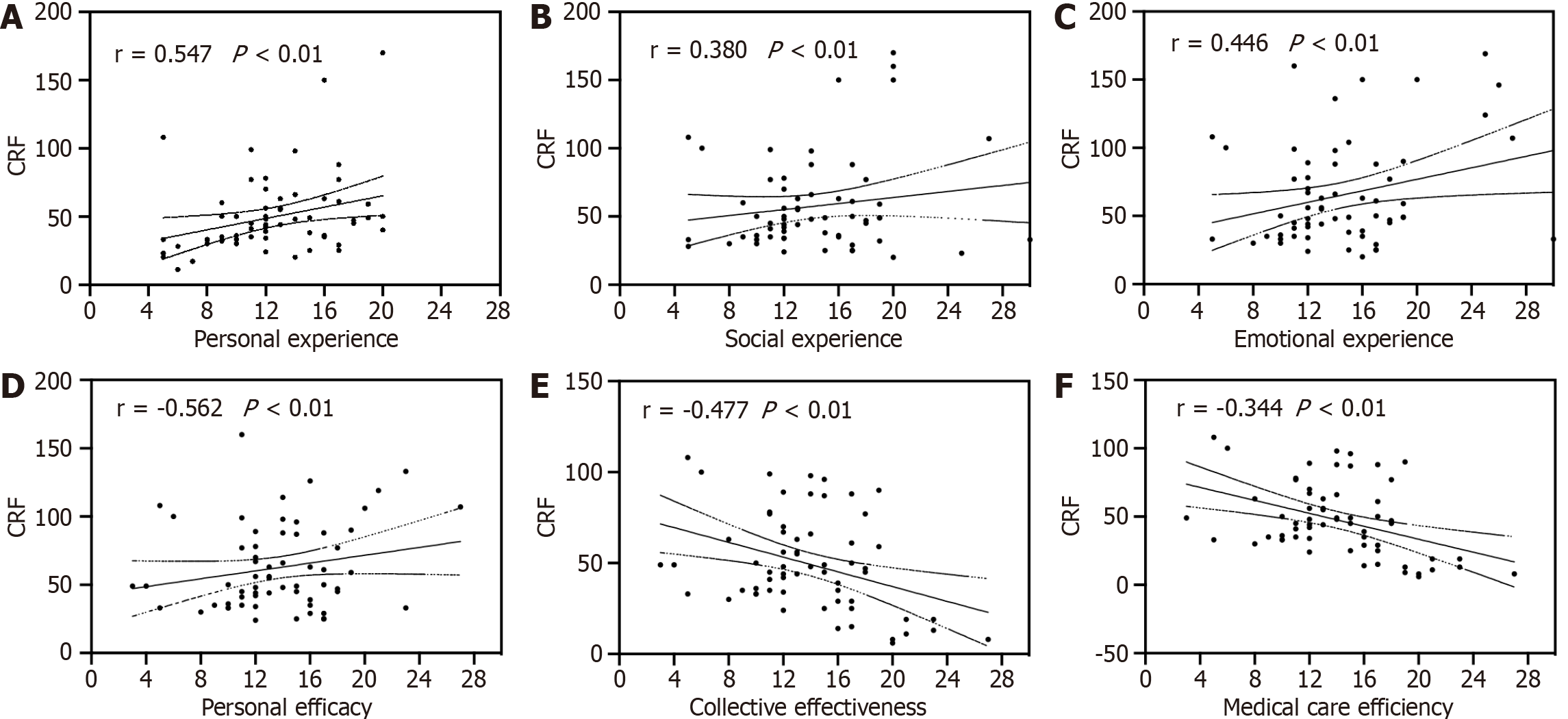

The correlation between CRF and perceptual control in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy is shown in Figure 3. The CRF score was positively correlated with cancer experience (all P < 0.01) and negatively correlated with cancer treatment efficacy (all P < 0.01).

As shown in Table 8, tumor stage, chemotherapy cycle, self-efficacy level, and anxiety and depression level were related to CRF in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy.

| Factor | Regression coefficient | Wald χ2 value | P value | OR |

| Tumor staging | 0.459 | 5.440 | 0.015 | 1.583 |

| Chemotherapy cycle | 0.233 | 4.629 | 0.003 | 1.339 |

| Self-efficacy level | 0.559 | 8.429 | 0.004 | 1.274 |

| Anxiety and depression level | 0.460 | 8.340 | 0.001 | 1.674 |

CRF is a subjective feeling of lack of passion, weakness, lack of concentration, and a tendency to feel tired[17]. CRF is the most common symptom in cancer treatment, and its duration and intensity vary from person to person. Along with experiencing a significant decrease in physical strength, patients with CRF also have other negative symptoms, such as disinterest in their surroundings or self-doubt. These symptoms not only impact their daily lives but also pose a significant threat to their rehabilitation and overall quality of life[18]. This study focused on factors that influence CRF, anxiety, and depression in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy because our understanding is currently limited and inconclusive.

Chemotherapy is the primary treatment for DLBCL. However, chemotherapy drugs may also kill normal cells. The occurrence of CRF during chemotherapy aggravates patients' negative emotions, which is not conducive to improving quality of life[19]. Most DLBCL patients have sleep disorders during chemotherapy, which may result from negative emotions surrounding the disease and the side effects of chemotherapy[20]. In This study investigated the status of CRF in patients with DLBCL. We observed that the overall average level of CRF in 62 patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy was 5.74 ± 2.51, of which 25 patients had the highest rate of mild fatigue in the cognitive dimension, and 35 patients had the highest moderate fatigue rate in the behavioral dimension. In the emotional dimension, the rate of severe fatigue was the highest in 34 cases. Therefore, it is of great significance to improve patients' cognitive level of fatigue and propose positive and effective measures to improve the degree of fatigue, promote their physical recovery, and improve their quality of life.

Patients with DLBCL must endure pain and discomfort caused by malignant tumors as well as adverse reactions caused by long-term chemotherapy[21]. Additionally, hospitalization can lead to a disruption of interpersonal communication and a sense of isolation, which often result in negative emotions such as anxiety and depression[22]. Previous studies have confirmed that alleviating negative emotions, such as tension, anxiety, and depression, and improving social and family psychological support reduced fatigue and improved their quality of life[23]. In addition, patients with advanced-stage disease may face increased mental stress and worry about the effectiveness of cancer treatment and their prognosis, which aggravates CRF[24]. Our study found that the severity of CRF in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy in a state of depression and anxiety was significantly higher than it was in patients without depression and anxiety. The level of depression and anxiety significantly influenced CRF. The reason may be that patients with depression and anxiety are in a state of depression and slow thinking for a long time and are more likely to feel tired. Furthermore, antidepressants such as mirtazapine and paroxetine have side effects that make patients tired and sleepy, which might also aggravate CRF.

The results of this study indicate that the CRF score was positively correlated with the cancer experience score in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy. The reasons might be as follows. The higher the score of the cancer experience, the more serious the hostile experience of patients during chemotherapy, and patients with CRF often experience fatigue in behavior, emotion, feeling, and cognition. Patients experience physical fatigue and weakness that leave them unable to carry out daily tasks, worsening their negative personal, social, and emotional wellbeing, and leading to an increased cancer experience score. Furthermore, we found that the CRF score was negatively correlated with cancer treatment effectiveness in these 62 patients with DLBCL. The reasons might be as follows. Higher cancer treatment efficacy scores reflect stronger belief in disease control, and a more optimistic perception of cancer. Patients with high personal efficacy scores have more vital personal management ability, a more robust ability to control their experience of the disease, better psychological adjustment and self-care, and a reduced degree of CRF.

Our results demonstrated that clinical stage significantly influenced CRF in this group of patients The reasons might be as follows. Patients with advanced-stage disease have lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, resulting in more severe symptoms of fatigue. As the disease progresses, tumors may invade more organs and tissues, causing damage to multiple systems in the body. This not only increases the complexity of treatment but may also lead to more severe fatigue symptoms[25]. Patients with advanced DLBCL may have more comorbidities and complications, which can themselves lead to fatigue and worsen during chemotherapy. Additionally, the diagnosis and treatment of advanced cancer can have a negative impact on a patient's mental state, resulting in anxiety, depression, and pessimism, which are known risk factors of CRF[26]. Therefore, managing CRF in patients with clinically advanced DLBCL requires a comprehensive approach that includes symptom alleviation strategies, psychological support, rehabilitation training, and measures to improve quality of life. Healthcare professionals should be aware of the seriousness of CRF and consider this important issue in planning treatment to improve patient quality of life and treatment satisfaction.

The study has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small. Further research is warranted to validate and expand upon these findings, incorporating larger and more diverse patient populations. Furthermore, the study design might not have accounted for all potential confounding variables that could have influenced the results. Future research should consider controlling for these factors to ensure more accurate and reliable conclusions. Lastly, the findings of this study may be limited by the specific timeframe in which the data was collected. Future research should consider using objective measures to validate the findings.

In summary, tumor staging, chemotherapy cycle, self-efficacy level, and anxiety and depression levels were factors related to CRF in patients with DLBCL during chemotherapy. In the clinic, it is necessary to make reasonable treatment and nursing plans for patients with DLBCL combined with the clinical characteristics of CRF to improve their clinical symptoms, treatment effectiveness, and survival rate.

| 1. | Nastoupil LJ, Bartlett NL. Navigating the Evolving Treatment Landscape of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:903-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tilly H, Gomes da Silva M, Vitolo U, Jack A, Meignan M, Lopez-Guillermo A, Walewski J, André M, Johnson PW, Pfreundschuh M, Ladetto M; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26 Suppl 5:v116-v125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 58.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kanas G, Ge W, Quek RGW, Keeven K, Nersesyan K, Jon E Arnason. Epidemiology of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL) in the United States and Western Europe: population-level projections for 2020-2025. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022;63:54-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liang XJ, Song XY, Wu JL, Liu D, Lin BY, Zhou HS, Wang L. Advances in Multi-Omics Study of Prognostic Biomarkers of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:1313-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shouse G, Herrera AF. Advances in Immunotherapy for Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. BioDrugs. 2021;35:517-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Thong MSY, van Noorden CJF, Steindorf K, Arndt V. Cancer-Related Fatigue: Causes and Current Treatment Options. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li H, Liu H. Combined effects of acupuncture and auricular acupressure for relieving cancer-related fatigue in patients during lung cancer chemotherapy: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e27502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang S, Chu S, Gao Y, Ai Q, Liu Y, Li X, Chen N. A Narrative Review of Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) and Its Possible Pathogenesis. Cells. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Machado P, Morgado M, Raposo J, Mendes M, Silva CG, Morais N. Effectiveness of exercise training on cancer-related fatigue in colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:5601-5613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sadeghian M, Rahmani S, Zendehdel M, Hosseini SA, Zare Javid A. Ginseng and Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73:1270-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Di Meglio A, Martin E, Crane TE, Charles C, Barbier A, Raynard B, Mangin A, Tredan O, Bouleuc C, Cottu PH, Vanlemmens L, Segura-Djezzar C, Lesur A, Pistilli B, Joly F, Ginsbourger T, Coquet B, Pauporte I, Jacob G, Sirven A, Bonastre J, Ligibel JA, Michiels S, Vaz-Luis I. A phase III randomized trial of weight loss to reduce cancer-related fatigue among overweight and obese breast cancer patients: MEDEA Study design. Trials. 2022;23:193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Berardi A, Graziosi G, Ferrazzano G, Casagrande Conti L, Grasso MG, Tramontano M, Conte A, Galeoto G. Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of the Revised Piper Fatigue Scale in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yue T, Li Q, Wang R, Liu Z, Guo M, Bai F, Zhang Z, Wang W, Cheng Y, Wang H. Comparison of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Zung Self-Rating Anxiety/Depression Scale (SAS/SDS) in Evaluating Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. Dermatology. 2020;236:170-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Takahashi T, Saito J, Fujino M, Sato M, Kumano H. The Validity and Reliability of the Short Form of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Japan. Front Psychol. 2022;13:833381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zitser J, Allen IE, Falgàs N, Le MM, Neylan TC, Kramer JH, Walsh CM. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) responses are modulated by total sleep time and wake after sleep onset in healthy older adults. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0270095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schmidt-Hansen M, Bennett MI, Arnold S, Bromham N, Hilgart JS, Page AJ, Chi Y. Oxycodone for cancer-related pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;6:CD003870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tsai HY, Wang CJ, Mizuno M, Muta R, Fetzer SJ, Lin MF. Predictors of cancer-related fatigue in women with breast cancer undergoing 21 days of a cyclic chemotherapy. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2022;19:211-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xian X, Zhu C, Chen Y, Huang B, Xiang W. Effect of Solution-Focused Therapy on Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45:E663-E673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lin J, Yang T, Chen W, Qi X, Cao Y, Zheng X, Chen H, Sun L, Lin L. Zhengyuan capsules for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced cancer-related fatigue in stage IIIB-IV unresectable NSCLC: study protocol for a randomized, multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Thorac Dis. 2022;14:4560-4570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fox RS, Ancoli-Israel S, Roesch SC, Merz EL, Mills SD, Wells KJ, Sadler GR, Malcarne VL. Sleep disturbance and cancer-related fatigue symptom cluster in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:845-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wilson WH, Wright GW, Huang DW, Hodkinson B, Balasubramanian S, Fan Y, Vermeulen J, Shreeve M, Staudt LM. Effect of ibrutinib with R-CHOP chemotherapy in genetic subtypes of DLBCL. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1643-1653.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Paunescu AC, Copie CB, Malak S, Gouill SL, Ribrag V, Bouabdallah K, Sibon D, Rumpold G, Preau M, Mounier N, Haioun C, Jardin F, Besson C. Quality of life of survivors 1 year after the diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a LYSA study. Ann Hematol. 2022;101:317-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu W, Liu J, Ma L, Chen J. Effect of mindfulness yoga on anxiety and depression in early breast cancer patients received adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022;148:2549-2560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cheng V, Oveisi N, McTaggart-Cowan H, Loree JM, Murphy RA, De Vera MA. Colorectal Cancer and Onset of Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:8751-8766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | White B, Rafiq M, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, Hamilton W, Price S, Lyratzopoulos G. Risk of cancer following primary care presentation with fatigue: a population-based cohort study of a quarter of a million patients. Br J Cancer. 2022;126:1627-1636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | White B, Renzi C, Barclay M, Lyratzopoulos G. Underlying cancer risk among patients with fatigue and other vague symptoms: a population-based cohort study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2023;73:e75-e87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |