Published online May 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.653

Revised: January 13, 2024

Accepted: April 12, 2024

Published online: May 19, 2024

Processing time: 146 Days and 6.2 Hours

Depression is a common and serious psychological condition, which seriously affects individual well-being and functional ability. Traditional treatment me

To assess the effects of NET on depression and analyze changes in serum inflammatory factors.

This retrospective study enrolled 140 patients undergoing treatment for depression between May 2017 and June 2022, the observation group that received a combination of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and NET treatment (n = 70) and the control group that only received MBSR therapy (n = 70). The clinical effectiveness of the treatment was evaluated by assessing various factors, including the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD)-17, self-rating idea of suicide scale (SSIOS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and levels of serum inflammatory factors before and after 8 wk of treatment. The quality of life scores between the two groups were compared. Comparisons were made using t and χ2 tests.

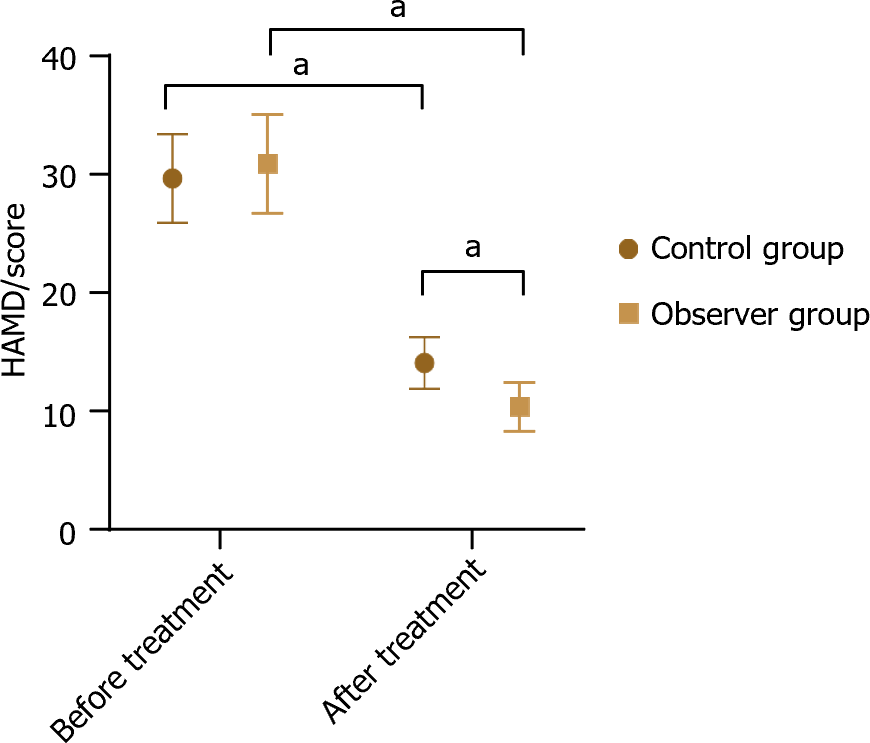

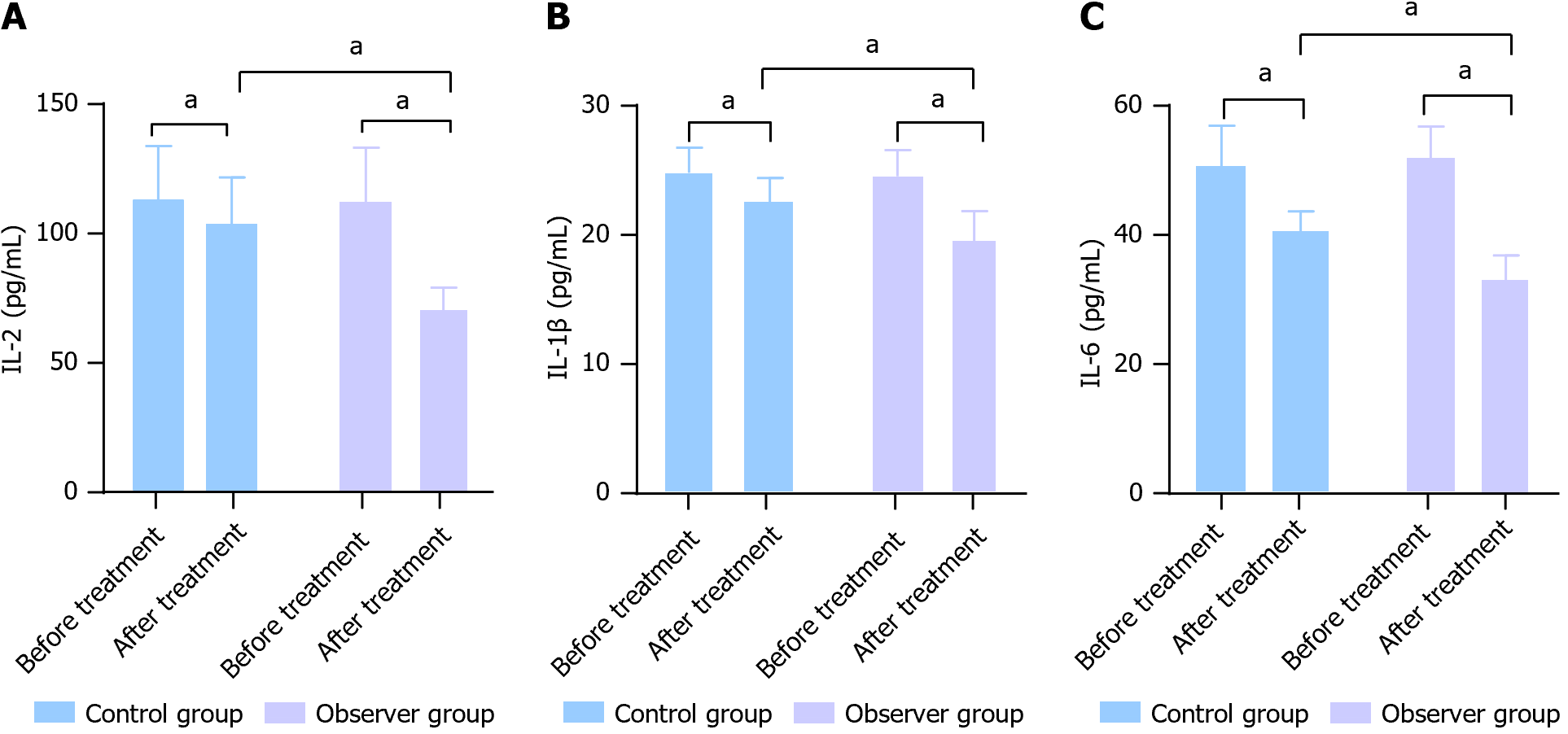

After 8 wk of treatment, the observation group exhibited a 91.43% overall effectiveness rate which was higher than that of the control group which was 74.29% (64 vs 52, χ2 = 7.241; P < 0.05). The HAMD, SSIOS, and PSQI scores showed a significant decrease in both groups. Moreover, the observation group had lower scores than the control group (10.37 ± 2.04 vs 14.02 ± 2.16, t = 10.280; 1.67 ±0.28 vs 0.87 ± 0.12, t = 21.970; 5.29 ± 1.33 vs 7.94 ± 1.35, t = 11.700; P both < 0.001). Additionally, there was a notable decrease in the IL-2, IL-1β, and IL-6 in both groups after treatment. Furthermore, the observation group exhibited superior serum inflammatory factors compared to the control group (70.12 ± 10.32 vs 102.24 ± 20.21, t = 11.840; 19.35 ± 2.46 vs 22.27 ± 2.13, t = 7.508; 32.25 ± 4.6 vs 39.42 ± 4.23, t = 9.565; P both < 0.001). Moreover, the observation group exhibited significantly improved quality of life scores compared to the control group (Social function: 19.25 ± 2.76 vs 16.23 ± 2.34; Emotions: 18.54 ± 2.83 vs 12.28 ± 2.16; Environment: 18.49 ± 2.48 vs 16.56 ± 3.44; Physical health: 19.53 ± 2.39 vs 16.62 ± 3.46; P both < 0.001) after treatment.

MBSR combined with NET effectively alleviates depression, lowers inflammation (IL-2, IL-1β, and IL-6), reduces suicidal thoughts, enhances sleep, and improves the quality of life of individuals with depression.

Core Tip: Nonconvulsive electrotherapy (NET) is a promising therapy for depression; however, its clinical effects and underlying mechanisms remain unclear. We conducted a retrospective analysis of data from 140 patients with depression. The control group received mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) therapy, whereas the observation group received a combination of MBSR therapy and NET. Alterations in serum inflammatory factor levels have been observed, suggesting that NET exerts a therapeutic effect by modulating inflammatory levels. This study provides valuable insights for future investigations of the mechanisms underlying the role of NET in depression.

- Citation: Gu ZW, Zhang CP, Chen LP, Huang X. Clinical effects of nonconvulsive electrotherapy combined with mindfulness-based stress reduction and changes of serum inflammatory factors in depression. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(5): 653-660

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i5/653.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.653

Depression is a common mental health disorder. Its clinical features mainly include continuous and long-term low mood, reduced interest, and decreased energy. The lifetime prevalence rate is 4.9%. It has a high incidence, repeated attacks, high disability rate, and low cure rate[1]. According to one survey, the prevalence of depression in China is approximately 6.8%. The prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) is 3.4%[2]. The annual prevalence of depression is increasing, accompanied by an increase in the complexity of treatment[3]. Studies have predicted that, by 2030, the burden of disease caused by depression will top the global list of mental illnesses[4]. Currently, drugs and psychotherapy are the main treatment methods; however, some limitations remain. Therefore, the identification of additional safe and effective treatment methods has become an important global concern.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is a type of psychotherapy, which focuses on guiding patients consciously and without judgment to perceive the present to alleviate and release negative emotions, enhance psychological well-being, and facilitate patient rehabilitation. To date, satisfactory results have been achieved in clinical applications[5]. Nonconvulsive electrotherapy (NET) is a novel method to improve nonconvulsive electroconvulsive therapy that aims to stimulate brain neurons without causing systemic convulsions[6]. The stimulation intensity of NET is between those of nonconvulsive electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation, and the side effects of the treatment are greatly reduced. Studies have shown that subthreshold stimulation without convulsions can achieve the same therapeutic effect as nonconvulsive electroconvulsive therapy[7]. However, there are relatively few studies from China on the use of NET for the treatment of depression. Accordingly, this study aimed to analyze the clinical effects of NET in the treatment of depression and observe the changes in serum inflammatory factors during treatment to provide a new treatment strategy for the clinical practice and enhance patient outcomes.

In this study, 140 patients with depression were enrolled from the Guangzhou HuiAi Hospital treatment program between May 2017 and June 2022. Based on the treatment method, the patients were divided into an observation group (n = 70) and a control group (n = 70). Criteria for inclusion were: (1) Individuals who fulfilled the clinical diagnostic criteria for depression according to Chinese Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Mental Disorders-3; (2) age ≥ 18 years; (3) Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD)-17 score >17; and (4) only MDD without other chronic diseases that affect mood and inflammatory factors. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Previous history of epilepsy; (2) alcohol dependence or drug abuse; (3) serious physical illness; (4) modified electroconvulsive therapy treatment in the past 2 months; and (5) obvious risk of suicide.

Both groups of patients were administered 10–20 mg escitalopram oxalate qd and did not take any other anti-anxiety, anti-depression, or other drugs. Based on drug treatment, the control group received MBSR treatment, whereas the observation group received mindfulness decompression combined with NET.

MBSR: One psychological consultant with secondary qualifications was the group leader, two third-level psychological consultants were deputy group leaders, and four experienced nursing staff cooperated. (1) Training time: the training time was 8 wk of centralized training. From the first week of admission, the patients chose to undergo treatment at any time of the day; (2) Training environment: A quiet and undisturbed health education room that met the requirements according to the quality control of MBSR, where the therapist introduced the relevant knowledge of MBSR; and (3) Training method: The patients were divided into seven groups according to the time of admission, with 10 patients per group. Each group underwent collective training for 180 min per session. The first 30 min were taught and explained by the doctor, the next 90 min were self-practice sessions, and the last 30 min were group discussions and summaries. The first week mainly comprised mindfulness eating raisins training; body sensation scanning was performed in the second week; the third week comprised mindfulness awareness breathing training; the fourth week included mindfulness stretching exercises; the fifth week comprised 3 min breathing spaces; the sixth week focused on the mindfulness-awareness idea; the seventh week included autonomous mindfulness awareness and experience, and mindful eating; and in the eighth week, all previous exercises were reviewed, summarized, and shared.

NET: Certain parameters were set to control the intensity of the electrical stimulation. The pulse width was 0.5 ms. Current, frequency, and duration were fixed at 0.9 A, 20 Hz, and 0.5-6.0 s, respectively. The setting of the current study was determined according to the age of the patient and was set to 1/8 of the patient’s age. Through a pre-experiment to observe the patient's right lower limb motor convulsions and EEG signals, the current was adjusted to avoid convulsions.

The treatment duration of both groups was 8 wk, and 1-2 times of MBSR were performed every week for 3 h. NET was performed for 30 min, three times a week, with a time interval of less than 2 d.

(1) Comparison of clinical effectiveness and HAMD-17 scores between the groups. Efficacy evaluation: Treatment outcomes for depression were assessed using the HAMD after an 8 wk period[8]. Cured: HAMD score 95%; markedly effective: HAMD score ≥ 8 points, decreased by 70%–95% compared with that before treatment; improvement: HAMD score ≥ 8 points, decreased by 50%–60% compared with that before treatment; ineffective: HAMD score decreased by < 50% compared with that before treatment. The total effective rate was calculated as follows: (cured + markedly effective + improvement )/total number of cases × 100%. A total of 17 items were included in the HAMD scale using a 5-level scoring method of 0 (none) to 4 (extremely severe) points or 0 to 2 points (0: None; 1: Mild-to-moderate; 2: Severe). The severity of the condition increased as the score increased; (2) We used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[9] to assess the sleep quality of patients before and after treatment. It consisted of 19 self-inspections and five other people's assessments, of which 18 items were categorized into seven factors: Sleep quality, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime functioning. Each factor was scored between 0 to 3 points. '0' refers to no difficulty, '3' refers to very difficult, and 21 points is the highest score. A total score ≥ 7 points indicated a sleep disorder. Sleep quality worsened as the score increased and vice versa; (3) The self-rating idea of suicide scale (SSIOS)[10] was employed to assess suicidal thoughts in both study groups prior to and following the intervention. There were 26 items, including four dimensions: optimism, sleep, despair, and cover-up. Possible answers are ‘yes‘ and ‘no.’ Higher scores indicate stronger suicidal ideation. If the total score on the scale is greater than or equal to 12 points, an individual can be considered to have suicidal ideation; (4) We compared alterations in serum inflammatory factors before and after therapy between the two groups. We collected 5 mL of fasting venous blood from all patients before and after eight weeks of treatment. The collected blood samples were then analyzed using ELISA kits to determine the serum IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-2 Levels. The detection steps were conducted meticulously following the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Xinxie Biological XinBio); and (5) Patients’ quality of life was assessed using the World Health Orga

SPSS software (version 20.0) was used to analyze descriptive variables, including age, HAMD scores, inflammatory factors, and other measurement data. to the data are presented as mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) t-tests were conducted to compare the groups. The treatment effect, sex, and other count data are presented as [n (%)], and comparisons between groups were performed using the χ2 test. Asymptotic significance was determined when the P value was < 0.05.

There were no significant differences in baseline data between the two groups (all P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Baseline information | Observer group (n = 70) | Control group (n = 70) | χ2/t value | P value |

| Sexuality [n (%)] | 0.029 | 0.866 | ||

| Males | 37 (52.86) | 36 (51.43) | ||

| Females | 33 (47.14) | 34 (48.57) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD/yr) | 44.62 ± 9.58 | 46.37 ± 9.42 | 1.090 | 0.278 |

| Course of disease (mean ± SD/yr) | 4.39 ± 0.44 | 4.31 ± 0.65 | 0.853 | 0.395 |

| HAMD (mean ± SD/score) | 30.88 ± 4.16 | 29.65 ± 3.72 | 1.844 | 0.067 |

There was no significant difference in HAMD scores between the observation and control groups before treatment (all P > 0.05). After treatment, we compared the HAMD scores between the two groups and found that the observation group exhibited lower scores than the control group (t = 10.280, P < 0.05; Figure 1).

After undergoing treatment for a period of 8 wk, the observation group achieved a significantly higher effective rate of 91.43% in comparison with the control group's rate of 74.29% (t = 21.970, t = 11.700; P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Groups | Recovery | Effectual | Improvement | Null and void | Total effective rates |

| Control group (n = 70) | 7 (10.00) | 14 (20.00) | 31 (44.29) | 18 (25.71) | 52 (74.29) |

| Observer group (n = 70) | 12 (17.14) | 20 (28.57) | 32 (45.72) | 6 (8.57) | 64 (91.43) |

| χ2/t value | 8.390 | 7.241 | |||

| P value | 0.039 | 0.007 | |||

Table 3 shows the SSIOS and PSQI scores for both groups which decreased after treatment compared to those before treatment. Additionally, the observation group had significantly lower scores than the control group (P < 0.05).

| Groups | Times | SSIOS/score | PSQI/score |

| Control group (n = 70) | Before treatment | 18.55 ± 4.02 | 15.83 ± 1.76 |

| After treatment | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 7.94 ± 1.35 | |

| t | 36.780 | 29.760 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Observer group (n = 70) | Before treatment | 18.88 ± 4.06 | 15.36 ± 2.54 |

| After treatment | 1.67 ± 0.28a | 5.29 ± 1.33a | |

| t value | 35.380 | 29.390 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

After 8 wk of treatment, IL-2, IL-1β, and IL-6 were noticeably reduced in both groups. Moreover, the observation group displayed enhanced levels of serum inflammatory factors compared to the control group (t = 11.840, t = 7.508, t = 9.565; all P < 0.05; Figure 2).

After undergoing treatment for 8 wk, the observation group showed a considerably enhanced quality of life compared to that of the control group (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Groups | Social function | Emotions | Environment | Physical health |

| Control group (n = 70) | 16.23 ± 2.34 | 12.28 ± 2.16 | 16.56 ± 3.44 | 16.62 ± 3.46 |

| Observer group (n = 70) | 19.25 ± 2.76 | 18.54 ± 2.83 | 18.49 ± 2.48 | 19.53 ± 2.39 |

| t value | 6.983 | 14.710 | 3.808 | 5.790 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

As a prevalent mental disorder, depression is characterized by high recurrence and disability, which greatly hampers patients’ social interaction, body health, and professional ability, consequently burdening society as a whole[12]. Therefore, providing timely and suitable medical interventions for individuals with depression is of immense importance[13,14]. In this study, by observing and comparing the clinical effects of mindfulness decompression alone and mind

The results showed a decrease in the HAMD, SSIOS, and PSQI scores in both groups following treatment, with the observation group exhibiting better outcomes than the control group. After undergoing treatment for 8 wk, the observation group showed a noticeable improvement in their quality of life score compared to the control group. This is because mindfulness decompression therapy enables patients to better deal with negative emotions and stress, and reduces the impact of depression on sleep by cultivating patients’ awareness and acceptance. Additionally, NET treatment improves the metabolic function of brain tissue, helps patients re-evaluate and adjust negative thinking patterns, and promotes sleep. The combination of these can more effectively alleviate depressive symptoms, reduce suicidal ideation, improve sleep quality and quality of life, and help patients recover.

In addition, research has discovered that inflammatory factors influence pathophysiological alterations associated with depression[15]. During the onset of depression, the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-2 increase, and the activation of immune-inflammatory pathways may affect monoamine and glutamatergic neurotransmission and contribute to the pathogenesis of severe depression in some patients[16-18]. Therefore, inflammatory factors can be used as a reflective index in patients with depression[19,20]. Research has indicated that the upregulation of IL-1β can energize and amplify the central inflammatory response, cause microglial pyroptosis, affect the plasticity of hippocampal synaptic cells, and induce and aggravate depressive symptoms[21]. IL-6 can lead to excessive hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity, which in turn causes fatigue, depression, and neurological symptoms[22]. The findings of this research indicated that the serum IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-2 Levels decreased following treatment in both groups. Additionally, the observation group exhibited notably improved levels of inflammatory factors compared with the control group. This indicates that mindfulness decompression combined with NET has a substantial impact on decreasing serum inflammatory factor levels in individuals with depression. This is because MBSR is a form of psychotherapy that can help patients reduce anxiety and stress and improve their mental state. Reducing psychological stress and negative emotions may reduce the production and release of inflammatory factors. In addition, NET stimulates neuronal activity by transmitting a weak current to the brain, regulates the release of neurotransmitters and the function of the neuroimmune system, and decreases the levels of pro-inflammatory substances.

This study has some limitations. We recruited a small sample of 140 individuals with depression. The selection of participants was limited, and no long-term follow-ups were conducted. In the future, the number of patients should be expanded, and a multicenter and large-sample survey should be conducted through a longitudinal study to further verify the results of this study.

Mindfulness decompression combined with NET can ameliorate depressive symptoms and improve sleep quality, effectively alleviate suicidal ideation, reduce inflammatory responses, and improve the quality of life of patients with depression. This combination exhibits remarkable clinical efficacy and deserves widespread clinical adoption.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Leaver AM, United States S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Li H, Luo X, Ke X, Dai Q, Zheng W, Zhang C, Cassidy RM, Soares JC, Zhang X, Ning Y. Major depressive disorder and suicide risk among adult outpatients at several general hospitals in a Chinese Han population. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, Yu Y, Kou C, Xu X, Lu J, Wang Z, He S, Xu Y, He Y, Li T, Guo W, Tian H, Xu G, Ma Y, Wang L, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Tan L, Zhang T, Ma C, Li Q, Ding H, Geng H, Jia F, Shi J, Wang S, Zhang N, Du X, Wu Y. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:211-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1590] [Cited by in RCA: 1360] [Article Influence: 226.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cipriani A, Salanti G, Furukawa TA, Egger M, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, Atkinson LZ, Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Ogawa Y, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Imai H, Shinohara K, Tajika A, Ioannidis JPA, Geddes JR. Antidepressants might work for people with major depression: where do we go from here? Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:461-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 2731] [Article Influence: 910.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Patel NK, Nivethitha L, Mooventhan A. Effect of a Yoga Based Meditation Technique on Emotional Regulation, Self-compassion and Mindfulness in College Students. Explore (NY). 2018;14:443-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zheng W, Jiang ML, He HB, Li RP, Li QL, Zhang CP, Zhou SM, Yan S, Ning YP, Huang X. A Preliminary Study of Adjunctive Nonconvulsive Electrotherapy for Treatment-Refractory Depression. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cai DB, Zhou HR, Liang WN, Gu LM, He M, Huang X, Shi ZM, Hou HC, Zheng W. Adjunctive Nonconvulsive Electrotherapy for Patients with Depression: a Systematic Review. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92:1645-1656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kato M, Baba H, Takekita Y, Naito M, Koshikawa Y, Bandou H, Kinoshita T. Usefulness of mirtazapine and SSRIs in late-life depression: post hoc analysis of the GUNDAM study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;79:1515-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen Z, Ren S, He R, Liang Y, Tan Y, Liu Y, Wang F, Shao X, Chen S, Liao Y, He Y, Li JG, Chen X, Tang J. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms among Chinese secondary school students. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lai Q, Huang H, Zhu Y, Shu S, Chen Y, Luo Y, Zhang L, Yang Z. Incidence and risk factors for suicidal ideation in a sample of Chinese patients with mixed cancer types. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:9811-9821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dionisie V, Puiu MG, Manea M, Pacearcă IA. Predictors of Changes in Quality of Life of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder-A Prospective Naturalistic 3-Month Follow-Up Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pelgrim CE, Peterson JD, Gosker HR, Schols AMWJ, van Helvoort A, Garssen J, Folkerts G, Kraneveld AD. Psychological co-morbidities in COPD: Targeting systemic inflammation, a benefit for both? Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;842:99-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tartt AN, Mariani MB, Hen R, Mann JJ, Boldrini M. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:2689-2699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 73.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Drevets WC, Wittenberg GM, Bullmore ET, Manji HK. Immune targets for therapeutic development in depression: towards precision medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:224-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 59.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kappelmann N, Arloth J, Georgakis MK, Czamara D, Rost N, Ligthart S, Khandaker GM, Binder EB. Dissecting the Association Between Inflammation, Metabolic Dysregulation, and Specific Depressive Symptoms: A Genetic Correlation and 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:161-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ng A, Tam WW, Zhang MW, Ho CS, Husain SF, McIntyre RS, Ho RC. IL-1β, IL-6, TNF- α and CRP in Elderly Patients with Depression or Alzheimer's disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan SY, Probert F, Radford-Smith DE, Hebert JC, Claridge TDW, Anthony DC, Burnet PWJ. Post-inflammatory behavioural despair in male mice is associated with reduced cortical glutamate-glutamine ratios, and circulating lipid and energy metabolites. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Suhee FI, Shahriar M, Islam SMA, Bhuiyan MA, Islam MR. Elevated Serum IL-2 Levels are Associated With Major Depressive Disorder: A Case-Control Study. Clin Pathol. 2023;16:2632010X231180797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ting EY, Yang AC, Tsai SJ. Role of Interleukin-6 in Depressive Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lamers F, Milaneschi Y, Smit JH, Schoevers RA, Wittenberg G, Penninx BWJH. Longitudinal Association Between Depression and Inflammatory Markers: Results From the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:829-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tian DD, Wang M, Liu A, Gao MR, Qiu C, Yu W, Wang WJ, Zhang K, Yang L, Jia YY, Yang CB, Wu YM. Antidepressant Effect of Paeoniflorin Is Through Inhibiting Pyroptosis CASP-11/GSDMD Pathway. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:761-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gong W, Chen J, Xu S, Li Y, Zhou Y, Qin X. The regulatory effect of Angelicae Sinensis Radix on neuroendocrine-immune network and sphingolipid metabolism in CUMS-induced model of depression. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;319:117217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |