Published online Apr 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i4.513

Peer-review started: January 25, 2024

First decision: February 8, 2024

Revised: February 22, 2024

Accepted: March 7, 2024

Article in press: March 7, 2024

Published online: April 19, 2024

Processing time: 82 Days and 22.6 Hours

Bronchial asthma is closely related to the occurrence of attention-deficit hyper

To explore the relationship between ADHD in children and bronchial asthma and to analyze its influencing factors.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Dongying People's Hospital from September 2018 to August 2023. Children diagnosed with ADHD at this hospital were selected as the ADHD group, while healthy children without ADHD who underwent physical examinations during the same period served as the control group. Clinical and parental data were collected for all participating children, and multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to identify risk factors for comorbid asthma in children with ADHD.

Significant differences were detected between the ADHD group and the control group in terms of family history of asthma and allergic diseases, maternal complications during pregnancy, maternal use of asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy, maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy, and parental relationship status (P < 0.05). Out of the 183 children in the ADHD group, 25 had comorbid asthma, resulting in a comorbidity rate of 13.66% (25/183), compared to the comorbidity rate of 2.91% (16/549) among the 549 children in the control group. The difference in the asthma comorbidity rate between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that family history of asthma and allergic diseases, maternal complications during pregnancy, maternal use of asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy, maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy, and parental relationship status are independent risk factors increasing the risk of comorbid asthma in children with ADHD (P < 0.05).

Children with ADHD were more likely to have comorbid asthma than healthy control children were. A family history of asthma, adverse maternal factors during pregnancy, and parental relationship status were identified as risk factors influencing the comorbidity of asthma in children with ADHD. Clinically, targeted interventions based on these factors can be implemented to reduce the risk of comorbid asthma. This information is relevant for results sections of abstracts in scientific articles.

Core Tip: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder in children. The incidence of ADHD has been increasing in recent years, which seriously affects children 's physical and mental health. Bronchial asthma is the most common chronic respiratory disease in children. Previous studies have shown that childhood asthma can increase the risk of ADHD and the core symptoms of ADHD. By exploring and analyzing the correlation between these two diseases and their influencing factors, this study will help to better understand the etiology of ADHD and provide reference for early prevention of ADHD.

- Citation: Wang GX, Xu XY, Wu XQ. Clarifying the relationship and analyzing the influential factors of bronchial asthma in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(4): 513-522

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i4/513.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i4.513

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder in children that is primarily characterized by persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity[1] and significantly impacts children's physical and mental health. The incidence of childhood ADHD has been on the rise in recent years. Incomplete statistics[2] show that the global prevalence of ADHD among children and adolescents has reached 7.2%, but the etiology and pathogenesis of ADHD have not yet been fully elucidated. Previous studies considered genetics to be the most crucial factor in ADHD, but recent research[3,4] has indicated that ADHD results from the interaction of multiple factors. Studies have shown[5] a close association between chronic childhood diseases and the development of ADHD. Bronchial asthma, characterized by recurrent coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, is a heterogeneous disease and the most common chronic respiratory disorder in children[6], adversely affecting their learning and social interactions. Previous research has suggested that asthma can increase children’s risk of developing ADHD and its core symptoms. Compared to children with ADHD alone, those with comorbid asthma tend to exhibit greater hyperactivity, hyperactive-impulsive behaviors, and anxiety, as well as more somatization and emotional internalization symptoms[7]. Therefore, exploring and analyzing the associations and influencing factors between these two diseases can enhance our understanding of the etiology of ADHD and provide new approaches for its early prevention and treatment. Currently, there is limited literature on the relationship between ADHD and asthma in children in China. This study aimed to analyze the occ

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Dongying People's Hospital from September 2018 to August 2023. As the study did not involve mandatory therapeutic interventions, all the data were anonymized prior to analysis and processing, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Children who were diagnosed with ADHD at our hospital between September 2018 and August 2023 were selected as the ADHD group, while children without ADHD who underwent physical examinations during the same period composed the healthy control group. The inclusion criteria for the ADHD group were as follows: (1) Children aged 4-14 years who met at least six of the nine ADHD symptom criteria as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition[8]; (2) children with a score ≥ 85 points on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; and (3) children with complete clinical records. The exclusion criteria included: (1) Comorbid psychiatric disorders; (2) the use of ADHD medication for more than one year; and (3) concurrent neurological abnormalities. The inclusion criteria for the healthy control group were children aged 4-14 years and children with complete clinical records, excluding those with developmental disorders, mental retardation, or neurological abnormalities.

The sample size calculation was based on previous studies reporting that the prevalence of ADHD and asthma in children was 9%[9] and 3.02%[10], respectively, with a comorbidity rate of 10.9%[11]. A 1:3 matching ratio was used [m = control group sample size (m0)/ADHD group sample size (n1) = 3]. With a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a power (β) of 0.2, the calculated sample size for the ADHD group was 183, and that for the control group was 549.

The data collected for both groups of children included sex, age, ethnicity, feeding method at birth, gestational age at delivery, history of brain injury, and family history of asthma and allergic diseases. Parental data, including highest educational level, average monthly household income, maternal complications during pregnancy, maternal use of asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy, and parental relationship status, were also collected.

Methods data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 and graphically represented using GraphPad Prism 8. Normally distributed quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared using t tests. Categorical data are expressed as the number of patients and were compared using chi-square tests. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was utilized to identify risk factors for comorbid asthma in children with ADHD. The statistical significance threshold was set at P < 0.05.

There was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of children with a family history of asthma and allergic diseases between the ADHD and control groups (P < 0.05). No significant differences in the remaining clinical data were found between the two groups (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 1.

| Parameter | ADHD group (n = 183) | Control group (n = 549) | χ2/t | P value |

| Sex (cases) | ||||

| Male | 96 | 283 | 0.046 | 0.831 |

| Female | 87 | 266 | ||

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 9.41 ± 1.68 | 9.62 ± 1.77 | 1.407 | 0.160 |

| Ethnicity (cases) | ||||

| Han | 171 | 517 | 0.129 | 0.720 |

| Non-Han | 12 | 32 | ||

| Feeding method (cases) | ||||

| Breastfed | 121 | 383 | 0.985 | 0.611 |

| Formula-fed | 26 | 74 | ||

| Mixed feeding | 36 | 92 | ||

| Gestational Age at Birth (wk) | ||||

| Full-term | 155 | 469 | 0.315 | 0.855 |

| Preterm | 16 | 50 | ||

| Postterm | 12 | 30 | ||

| Brain Injury (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 6 | 0.338 | 0.561 |

| No | 180 | 543 | ||

| Family history of asthma/allergic diseases (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 41 | 65 | 12.371 | < 0.001 |

| No | 142 | 484 |

Significant differences were observed between the ADHD and control groups concerning maternal complications during pregnancy, maternal use of asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy, maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy, and parental relationship status (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the other parental data between the two groups (P > 0.05), as detailed in Table 2.

| Parameter | ADHD group (n = 183) | Control group (n = 549) | χ2/t | P value |

| Parental highest educational level (cases) | ||||

| Junior high school or below | 41 | 125 | 0.160 | 0.923 |

| High school or vocational school | 54 | 169 | ||

| College degree or above | 88 | 255 | ||

| Average monthly household income (cases) | ||||

| < 5000 RMB | 95 | 290 | 0.046 | 0.831 |

| ≥ 5000 RMB | 88 | 259 | ||

| Maternal pregnancy complications (cases) | ||||

| Present | 31 | 42 | 13.191 | < 0.001 |

| Absent | 152 | 507 | ||

| Use of asthma/allergy medications during pregnancy (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 38 | 59 | 11.981 | 0.001 |

| No | 145 | 490 | ||

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 26 | 75 | 0.034 | 0.853 |

| No | 157 | 474 | ||

| Maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 28 | 39 | 11.091 | 0.001 |

| No | 155 | 510 | ||

| Parental relationship status (cases) | ||||

| Good | 141 | 424 | 20.052 | < 0.001 |

| Average | 23 | 109 | ||

| Poor | 19 | 16 |

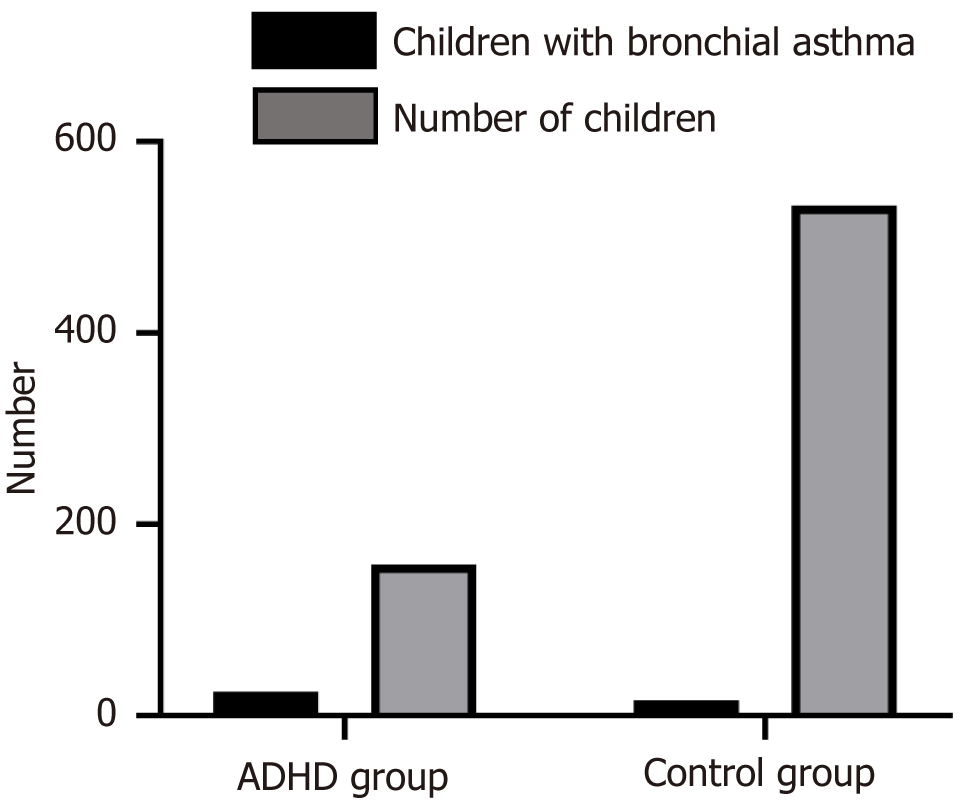

Among the 183 children in the ADHD group, 25 had comorbid asthma, resulting in a comorbidity rate of 13.66% (25/183). Among the 549 children in the control group, 16 had comorbid asthma, resulting in a comorbidity rate of 2.91% (16/549). The difference in the asthma comorbidity rate between the two groups was statistically significant (χ² = 29.981, P < 0.001), as illustrated in Figure 1.

Significant differences were observed between children with ADHD with and without comorbid asthma in terms of family history of asthma and allergic diseases, maternal complications during pregnancy, maternal use of asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy, maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy, and parental relationship status (P < 0.05). No significant differences were found in the other clinical data between the two groups (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 3.

| Parameter | Comorbid group (n = 25) | Non-comorbid group (n = 158) | χ2/t | P value |

| Sex (cases) | ||||

| Male | 13 | 83 | 0.002 | 0.961 |

| Female | 12 | 75 | ||

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 9.35 ± 1.72 | 9.49 ± 1.63 | 0.396 | 0.693 |

| Ethnicity (cases) | ||||

| Han | 23 | 148 | 0.098 | 0.754 |

| Non-Han | 2 | 10 | ||

| Feeding method (cases) | ||||

| Breastfed | 16 | 105 | 0.395 | 0.821 |

| Formula-fed | 3 | 23 | ||

| Mixed feeding | 6 | 30 | ||

| Gestational age at birth (wk, cases) | ||||

| Full-term | 21 | 134 | 0.642 | 0.726 |

| Preterm | 3 | 13 | ||

| Postterm | 1 | 11 | ||

| Brain injury (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 2 | 1.007 | 0.317 |

| No | 24 | 156 | ||

| Family history of asthma/allergic diseases (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 32 | 32.821 | < 0.001 |

| No | 16 | 517 | ||

| Maternal pregnancy complications (cases) | ||||

| Present | 16 | 15 | 45.581 | < 0.001 |

| Absent | 9 | 143 | ||

| Maternal use of asthma/allergy medications during pregnancy (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 20 | 46.201 | < 0.001 |

| No | 7 | 138 | ||

| Maternal smoking history during pregnancy (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 22 | 0.076 | 0.782 |

| No | 21 | 136 | ||

| Maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy (cases) | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 13 | 44.641 | < 0.001 |

| No | 10 | 145 | ||

| Parental relationship status (cases) | ||||

| Good | 10 | 131 | 36.952 | < 0.001 |

| Average | 4 | 19 | ||

| Poor | 11 | 8 |

Using comorbid asthma in children with ADHD as the dependent variable and the statistically significant items from the univariate analysis as independent variables (variable assignment details are shown in Table 4), a multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted using stepwise regression, with an inclusion criterion of 0.10 and an exclusion criterion of 0.05. The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that a family history of asthma and allergic diseases, maternal complications during pregnancy, maternal use of asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy, maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy, and parental relationship status were independent risk factors for comorbid asthma in children with ADHD (P < 0.05), as presented in Table 5.

| Variable | Assignment method |

| Family history of asthma/allergic diseases | No = 0, Yes = 1 |

| Maternal pregnancy complications | No = 0, Yes = 1 |

| Maternal use of asthma/allergy medications during pregnancy | No = 0, Yes = 1 |

| Maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy | No = 0, Yes = 1 |

| Parental relationship | Poor = 1, Average = 2, Good = 3 |

| Factors | β | SE | Ward χ2 | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Family history of asthma/allergic diseases | 0.992 | 0.339 | 7.944 | < 0.001 | 2.697 | 1.353-5.377 |

| Maternal pregnancy complications | 0.813 | 0.367 | 5.747 | < 0.001 | 2.254 | 1.160-4.380 |

| Maternal use of asthma/allergy medications during pregnancy | 1.098 | 0.341 | 8.950 | < 0.001 | 2.998 | 1.460-6.155 |

| Maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy | 0.933 | 0.388 | 7.485 | < 0.001 | 2.542 | 1.303-4.960 |

| Parental relationship status | 0.686 | 0.339 | 3.122 | 0.029 | 1.985 | 0.928-4.247 |

In recent years, there has been an increase in both national and international reports on children with ADHD with comorbid asthma. Studies[12] have indicated that approximately 35 out of every 100 children with ADHD have allergic diseases, with 25 having comorbid asthma. Our retrospective study analyzing the clinical data of 183 children with ADHD showed that 25 out of the 183 children in the ADHD group had comorbid asthma, resulting in a comorbidity rate of 13.66%, which is significantly lower than the rates reported in foreign literature[13]. This discrepancy might be attributed to the smaller sample size of our study compared to larger-scale population studies, which offer greater representativeness and can more accurately reflect the overall situation of comorbid asthma in children with ADHD. Previous research[14] has suggested that asthma control levels are lower in children with ADHD who also have oppositional defiant disorder, possibly due to lower medication adherence in these children. Asthma also impacts ADHD, with studies reporting[15] that asthma increases the risk of developing ADHD, and children with multiple airway hyperreactivity diseases have a greater risk of ADHD than those with a singular airway hyperreactivity disease. Moreover, asthma increases the severity of core ADHD symptoms; children diagnosed with asthma are more likely to exhibit symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity and have comorbid ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder. Studies[16] have shown that children with both asthma and ADHD are more likely to exhibit higher levels of hyperactivity, hyperactivity-impulsivity, externalized behavior, anxiety, somatization, and emotional internalization symptoms than are children with ADHD alone. Therefore, exploring the factors influencing comorbid asthma in children with ADHD is crucial.

The correlation between asthma and ADHD has been confirmed in multiple studies. Cortese et al[17], through meta-analyses and population studies, found a significant correlation between asthma and ADHD. This correlation remained significant even after adjusting for variables such as sex, birth year, birth weight, maternal age during pregnancy, gestational age at birth, and family income. This study revealed a weak to moderate correlation between asthma and ADHD, as well as between other allergic diseases, such as eczema, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis, and ADHD. Our univariate and multivariate analyses indicated that a family history of asthma and allergic diseases, maternal complications during pregnancy, maternal use of asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy, maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy, and parental relationship status are independent risk factors influencing comorbid asthma in children with ADHD (P < 0.05). The reason may be that family history may play an important genetic role in the development of asthma, allergic diseases and ADHD. Some genes may increase the risk of asthma and allergic diseases in individuals and may also be related to ADHD. Maternal complications during pregnancy may have a negative impact on fetal development and health. The fetuses of mothers who experience complications are adversely affected in the womb, and the key organs, such as the brain and immune system, may be affected, increasing the risk of various diseases in the future, including ADHD and asthma. The use of some drugs, such as steroids and antihistamines, during pregnancy to treat asthma and allergic diseases may affect the neurodevelopment of the fetus. These drugs may penetrate the placenta and affect the development of the fetal brain, thereby increasing the risk of neurodevelopmental problems (such as ADHD) in children. Maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy can increase the secretion of cortisol, which reaches the fetus through the blood, affecting the development of the nervous system and increasing the risk of comorbid asthma in offspring who develop ADHD. Family conflict and poor parental relationships may lead to immune system disorders and increase the risk of asthma in children.

Both asthma and ADHD are diseases influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. The perinatal period is a particularly sensitive time when exposure to adverse factors may predispose children or adults to various diseases. Studies have shown[18] that the occurrence of childhood asthma is closely related to perinatal intrauterine and extrauterine environmental exposures. Maternal allergies during pregnancy involving the presence of certain allergens may alter the microenvironment and immune balance of the body, thus increasing the risk of asthma in offspring. Research by Wenderlich et al[19] revealed an increased incidence of ADHD in children whose parents had asthma, especially when the mother had asthma, with this association being more significant when both parents had asthma, suggesting that intrauterine exposure may also play a role. A study on a large and representative population[20] showed that parental use of asthma and allergic rhinitis medications increased the risk of offspring needing to use ADHD medication. Furthermore, studies have shown[21] that adverse maternal factors during pregnancy, including negative emotional states and exposure to toxic substances, can influence the development of comorbid asthma in children with ADHD. Maternal exposure to toxic substances during pregnancy can affect the normal growth and development of the fetus, especially central nervous system development, leading to abnormalities in brain function and an increased likelihood of ADHD in children. Maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy can affect cortisol secretion, leading to increased levels. Cortisol reaches the fetus through the bloodstream, affecting the development of the nervous system and increasing the risk of comorbid asthma in children with ADHD. Additional research[22] has shown that the quality of the parental relationship and the home environment impact children’s psychological health and immune system function. Family conflicts and poor parental relationships may lead to immune system dysregulation in children, increasing the risk of asthma.

In summary, children with ADHD are more prone to comorbid asthma than healthy controls are, with a family history of asthma, adverse maternal factors during pregnancy, and parental relationship status all being risk factors. Clinical interventions targeting these factors can reduce the risk of comorbid asthma. The retrospective nature and smaller sample size of our study may have introduced bias into the results. Future studies with larger sample sizes are planned to analyze the specific pathogenesis of comorbid asthma in children with ADHD. The limitation of this study is that the psychological mechanism of the children was not considered, and the relevant variables were mostly variables related to heredity, family history and parents. The main reason is that the children included in the study were 4 to 14 years old. The psychological differences of children in this age group are relatively large. Multivariate logistic regression analysis cannot specifically explain the impact of children's psychological development on comorbid ADHD and asthma. In the future, the sample size will be increased, and qualitative analysis, time series analysis and other methods will be combined to analyze the mechanism of children's psychological development.

The relationship between bronchial asthma and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and its pathogenesis have become a hot and difficult issue in the field of pediatrics. The latest large sample report based on the population confirmed that ADHD can be associated with a variety of allergic diseases, including bronchial asthma, but the specific relationship between the two and the related risk factors are unknown. Therefore, this study intends to preliminarily analyze the relationship between ADHD and asthma, and analyze the related risk factors, in order to further understand the relationship between them, avoid the exposure of related risk factors of bronchial asthma and ADHD children to reduce the risk of disease. In order to better clinical management of children with asthma and ADHD.

This study mainly analyzes the association between childhood asthma and ADHD and related risk factors, which is of great significance for the individualized clinical comprehensive management of these two diseases, and is helpful for clinical prevention and treatment according to the exposure of related risk factors.

This study mainly expounds the relationship between childhood asthma and ADHD. Individualized intervention measures for risk factors can effectively reduce the risk of asthma, and provide reference for the prevention and treatment of the pathogenesis of the two in the future.

In this study, a retrospective study was conducted to collect the clinical data and parental data of all selected children. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the risk factors of comorbid asthma in children with ADHD. Multivariate logistic regression analysis has the advantages of controllable covariate effect, model flexibility, and consideration of interaction, which can better and more comprehensively understand and explain the changes of dependent variables.

The results of this study found that ADHD children are more likely to suffer from asthma than healthy control children. Family history of asthma, adverse factors of mother during pregnancy, and parental relationship are all factors affecting the risk of comorbidity of asthma in ADHD children. Targeted interventions can be taken to reduce the risk of comorbidity of asthma. However, this study is a retrospective study, and the sample size is small, which may cause some bias to the research results. In the future, the sample size will be expanded to analyze the specific pathogenesis of ADHD children with asthma.

Through retrospective cohort study, this study further confirmed that ADHD children are more likely to suffer from asthma than healthy control children, and ADHD children are more likely to suffer from asthma than healthy control children, which is an important factor affecting the comorbidity of the two diseases.

In the follow-up study, the sample size will be further increased, and the specific pathogenesis of bronchial asthma will be analyzed according to the different clinical subtypes of ADHD.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kessler RC, United States; Young AH, United Kingdom S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Carbray JA. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2018;56:7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Drechsler R, Brem S, Brandeis D, Grünblatt E, Berger G, Walitza S. ADHD: Current Concepts and Treatments in Children and Adolescents. Neuropediatrics. 2020;51:315-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xue J, Hao Y, Li X, Guan R, Wang Y, Li Y, Tian H. Meta-Analysis Study on Treatment of Children's Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity. J Healthc Eng. 2021;2021:8229039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fawns T. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder. Prim Care. 2021;48:475-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Silverstein GD, Arcoleo K, Rastogi D, Serebrisky D, Warman K, Feldman JM. The Relationship Between Pediatric Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Asthma Management. J Adolesc Health. 2023;73:813-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu X, Dalsgaard S, Munk-Olsen T, Li J, Wright RJ, Momen NC. Parental asthma occurrence, exacerbations and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;82:302-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nirouei M, Kouchekali M, Sadri H, Qorbani M, Montazerlotfelahi H, Eslami N, Tavakol M. Evaluation of the frequency of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with asthma. Clin Mol Allergy. 2023;21:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Doernberg E, Hollander E. Neurodevelopmental Disorders (ASD and ADHD): DSM-5, ICD-10, and ICD-11. CNS Spectr. 2016;21:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Baweja R, Mattison RE, Waxmonsky JG. Impact of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder on School Performance: What are the Effects of Medication? Paediatr Drugs. 2015;17:459-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cao Y, Chen S, Chen X, Zou W, Liu Z, Wu Y, Hu S. Global trends in the incidence and mortality of asthma from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis using the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1036674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jiang XD, Shen C, Li K, Ji YT, Li SH, Jiang F, Shen XM, Li F, Hu Y. Impact of allergic airway diseases on risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in school-age children. Zhonghua Erke Zazhi. 2017;55:509-513. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang LJ, Yu YH, Fu ML, Yeh WT, Hsu JL, Yang YH, Chen WJ, Chiang BL, Pan WH. Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder is associated with allergic symptoms and low levels of hemoglobin and serotonin. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Galéra C, Cortese S, Orri M, Collet O, van der Waerden J, Melchior M, Boivin M, Tremblay RE, Côté SM. Medical conditions and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms from early childhood to adolescence. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:976-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Leffa DT, Caye A, Santos I, Matijasevich A, Menezes A, Wehrmeister FC, Oliveira I, Vitola E, Bau CHD, Grevet EH, Tovo-Rodrigues L, Rohde LA. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder has a state-dependent association with asthma: The role of systemic inflammation in a population-based birth cohort followed from childhood to adulthood. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;97:239-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kaas TH, Vinding RK, Stokholm J, Bønnelykke K, Bisgaard H, Chawes BL. Association between childhood asthma and attention deficit hyperactivity or autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:228-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Straughen JK, Sitarik AR, Wegienka G, Cole Johnson C, Johnson-Hooper TM, Cassidy-Bushrow AE. Association between prenatal antimicrobial use and offspring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0285163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cortese S, Sun S, Zhang J, Sharma E, Chang Z, Kuja-Halkola R, Almqvist C, Larsson H, Faraone SV. Association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis and a Swedish population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:717-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chang SJ, Kuo HC, Chou WJ, Tsai CS, Lee SY, Wang LJ. Cytokine Levels and Neuropsychological Function among Patients with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Atopic Diseases. J Pers Med. 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wenderlich AM, Baldwin CD, Fagnano M, Jones M, Halterman J. Responsibility for Asthma Management Among Adolescents With and Without Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65:812-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kiani A, Houshmand H, Houshmand G, Mohammadi Y. Comorbidity of asthma in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) aged 4-12 years in Iran: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85:2568-2572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Park HJ, Kim YH, Na DY, Jeong SW, Lee MG, Lee JH, Yang YN, Kang MG, Yeom SW, Kim JS. Long-term bidirectional association between asthma and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A big data cohort study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1044742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pan PY, Taylor MJ, Larsson H, Almqvist C, Lichtenstein P, Lundström S, Bölte S. Genetic and environmental contributions to co-occurring physical health conditions in autism spectrum condition and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Mol Autism. 2023;14:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |