Published online Feb 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.255

Peer-review started: November 3, 2023

First decision: November 16, 2023

Revised: November 29, 2023

Accepted: January 16, 2024

Article in press: January 16, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2024

Processing time: 95 Days and 2.6 Hours

Cancer patients often suffer from severe stress reactions psychologically, such as anxiety and depression. Prostate cancer (PC) is one of the common cancer types, with most patients diagnosed at advanced stages that cannot be treated by radical surgery and which are accompanied by complications such as bodily pain and bone metastasis. Therefore, attention should be given to the mental health status of PC patients as well as physical adverse events in the course of clinical treat

To analyze the risk factors leading to anxiety and depression in PC patients after castration and build a risk prediction model.

A retrospective analysis was performed on the data of 120 PC cases treated in Xi'an People's Hospital between January 2019 and January 2022. The patient cohort was divided into a training group (n = 84) and a validation group (n = 36) at a ratio of 7:3. The patients’ anxiety symptoms and depression levels were asse

In the training group, 35 patients and 37 patients had an SAS score and an SDS score greater than or equal to 50, respectively. Based on the scores, we further subclassified patients into two groups: a bad mood group (n = 35) and an emotional stability group (n = 49). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score were independent risk factors affecting a patient's bad mood (P < 0.05). In the training and validation groups, patients with adverse emotions exhibited significantly higher risk scores than emotionally stable patients (P < 0.0001). The area under the curve (AUC) of the risk prediction model for predicting bad mood in the training group was 0.743, the specificity was 70.96%, and the sensitivity was 66.03%, while in the validation group, the AUC, specificity, and sensitivity were 0.755, 66.67%, and 76.19%, respectively. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed a χ2 of 4.2856, a P value of 0.830, and a C-index of 0.773 (0.692-0.854). The calibration curve revealed that the predicted curve was basically consistent with the actual curve, and the calibration curve showed that the prediction model had good discrimination and accuracy. Decision curve analysis showed that the model had a high net profit.

In PC patients, marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative pain (VAS) score are important factors affecting postoperative anxiety and depression. The logistic regression model can be used to successfully predict the risk of adverse psychological emotions.

Core Tip: Postoperative anxiety and depression are common and serious psychological problems in patients with prostate cancer, and marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative pain score have been identified as important factors leading to these psychological problems. Establishing a predictive model based on logistic regression can facilitate effective evaluation of patients’ psychological risk and provide guidance for individualized intervention measures. By paying attention to patients' mental health, health care professionals can improve the quality of life and prognosis of patients. However, further research is needed to validate these findings and continue to explore other possible influencing factors, with the objective of developing more precise intervention strategies and support measures to meet the mental health needs of prostate cancer patients.

- Citation: Li RX, Li XL, Wu GJ, Lei YH, Li XS, Li B, Ni JX. Analysis of risk factors leading to anxiety and depression in patients with prostate cancer after castration and the construction of a risk prediction model. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(2): 255-265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i2/255.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.255

Prostate cancer (PC) is a common malignancy affecting older men[1]. Worldwide, PC ranks second in the incidence of male malignancies and fifth in mortality[2]. In the United States, the incidence of PC has risen to the top of the list as the tumor that poses the greatest threat to men's health[3]. Although less prevalent than in Europe and America, PC shows an increasing incidence year by year in China and has become the main type of urinary system malignancy since 2008[4]. There are many therapeutic strategies for PC, including surgery, radiotherapy, and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)[5]. ADT is the major treatment for PC patients due to the atypical early symptoms of the disease that result in disease progression to a higher stage when diagnosed[2]. For ADT, castration can be performed either surgically by removing both testicles or medically by using drugs to block the production of male hormones in the testicles. Surgical castration is usually a simple procedure with few side effects, but for many men, it is a major decision concerning body image and gender identity[6]. Although medical castration can store male hormone production after treatment discontinuation, it may cause some side effects, such as flushing, decreased libido, and impotence[7]. Nevertheless, surgical castration may still be an effective treatment option for PC patients who are ineligible for drug treatment.

The stress that PC patients experience comes not only from the physical symptoms of the disease and the side effects of treatment but also from the psychological and social issues associated with stigma[8]. While methods such as surgery and endocrine therapy can improve survival in PC patients, they may have a serious negative impact on their physical and mental health[9]. The medical model is shifting from a single physiological level to a comprehensive psychological, social and physiological model that extends beyond physical symptoms; therefore, more attention is expected to be given to patients’ psychological conditions, such as anxiety and depression, when treating PC[10]. Malignant tumors, surgical trauma, and postoperative complications may bring enormous mental pressure to patients, resulting in important negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and pessimism[11]. Therefore, in the process of treating PC, doctors and medical teams need to pay close attention to patients' mental health and provide timely psychological counseling and support to help patients cope with various challenges brought by the disease.

Risk prediction models play a central role in many fields, including but not limited to medical care, finance, insurance, and industry[12]. Their major function is to support decision-making. For example, doctors can use models to evaluate patients' disease risk and develop personalized treatment and prevention plans accordingly. In this study, we built a risk prediction model to predict anxiety and depression in PC patients after surgical castration, providing a reference for clinical treatment and intervention.

After obtaining approval from the Xi'an People's Hospital Medical Ethics Committee, a retrospective analysis was conducted on the data of 148 PC patients who received treatment in Xi'an People's Hospital between January 2019 and January 2022.

The inclusion criteria are listed as follows: Age range: 30-75; confirmed diagnosis of PC by prostate puncture or postoperative pathology; clear mind, good cooperation, and ability to independently complete various questionnaires; intact clinical data.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: Serious dysfunction of vital organs such as the heart and lung; history of organic brain diseases or mental illness; concomitant other tumors; and life expectancy ≤ 6 months.

One hundred and twenty PC patients were selected after rigorous screening according to the patient eligibility and exclusion criteria mentioned above. They were assigned to a training group (n = 84) and a validation group (n = 36) at a ratio of 7:3. Furthermore, they were assessed by the Self-rating Anxiety and Depression Scale (SAS/SDS)[13] for anxiety symptoms and depression levels two weeks after surgery, with a score of more than 50 on both scales indicating the presence of anxiety and depression.

By reviewing patients' electronic medical records, we collected the following clinical data: Age, education level, marital status, employment, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, alcoholism history, hypertension, diabetes, castration scheme, monthly income, and postoperative pain level. In addition, SAS and SDS scores were collected after 2 wk of treatment.

The data collected were analyzed and processed by SPSS 26.0. Continuous variables conforming to a normal distribution are described as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by the two independent samples t test. Categorical variables, expressed as percentages (%), were tested by the χ2 test. Variables with a P value less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, and the independent risk factors for anxiety and depression in PC patients were screened using the stepwise regression procedure. Using R software and the RMS package, a nomogram for the prediction of bad mood in PC patients was established; the operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the subjects were drawn, and the areas under the curve (AUCs) were calculated. The calibration curve and decision curve were plotted to verify the effectiveness of the model. Statistical significance was indicated by P values less than P < 0.05.

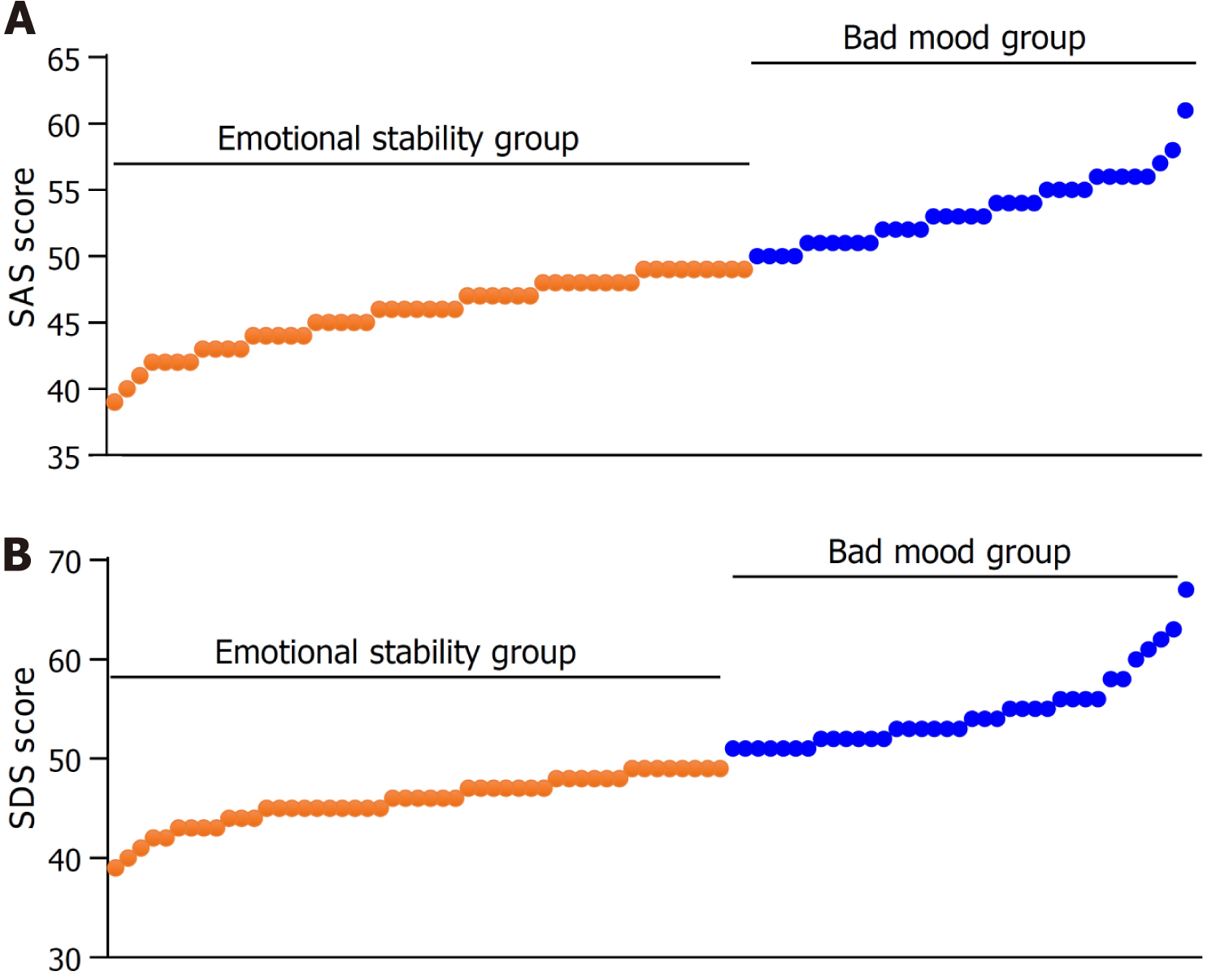

Patients’ anxiety and depression were evaluated by the SAS and SDS at 2 wk after treatment. The results showed that 35 patients had SAS scores greater than or equal to 50 points, and 37 patients had SDS scores greater than or equal to 50 points (Figure 1). By further comparing patients' baseline data between the training and validation sets, we found no statistical difference between the two groups (P > 0.05). Based on the scores, we further assigned the patients to a bad mood group (n = 35) and an emotional stability group (n = 49) for univariate analysis (Table 1).

| Factors | Training group (n = 84) | Validation group (n = 36) | P value | |

| Age | 0.871 | |||

| ≥ 60 years old | 34 | 14 | ||

| < 60 years old | 50 | 22 | ||

| Education level | 0.274 | |||

| ≥ High school | 37 | 12 | ||

| < High school | 47 | 24 | ||

| Marital status | 0.999 | |||

| Married | 56 | 24 | ||

| Divorced/unmarried | 28 | 12 | ||

| Employment | 0.545 | |||

| Employed | 19 | 10 | ||

| Retired | 65 | 26 | ||

| BMI | 0.668 | |||

| ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 18 | 9 | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 66 | 27 | ||

| Smoking history | 0.624 | |||

| With | 62 | 25 | ||

| Without | 22 | 11 | ||

| History of alcoholism | 0.373 | |||

| With | 13 | 8 | ||

| Without | 71 | 28 | ||

| Hypertension | 0.593 | |||

| With | 15 | 5 | ||

| Without | 69 | 31 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.451 | |||

| With | 18 | 10 | ||

| Without | 66 | 26 | ||

| Castration scheme | 0.778 | |||

| Surgery | 35 | 16 | ||

| Medication | 49 | 20 | ||

| Monthly income | 0.807 | |||

| ≥ 4500 RMB | 33 | 15 | ||

| < 4500 RMB | 51 | 21 | ||

| Postoperative VAS score | 0.777 | |||

| ≥ 5 points | 19 | 9 | ||

| < 5 points | 65 | 27 | ||

| Unhealthy emotions | ||||

| Bad mood group | 35 | 15 | ||

| Emotional stability group | 49 | 21 | 0.999 |

Clinical data were evaluated after patients were grouped according to their scores. Statistical differences were present in marital status, castration scheme, monthly income, and postoperative Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score between patients with bad mood and those with emotional stability (P < 0.05; Table 2), while no significant difference was identified in age, education level, employment, BMI, smoking history, alcoholism history, hypertension, or diabetes (P > 0.05).

| Factors | Bad mood group (n = 35) | Emotional stability group (n = 49) | P value | |

| Age | 0.645 | |||

| ≥ 60 years old | 15 | 19 | ||

| < 60 years old | 20 | 30 | ||

| Education level | 0.249 | |||

| ≥ High school | 18 | 19 | ||

| < High school | 17 | 30 | ||

| Marital status | 0.034a | |||

| Married | 28 | 28 | ||

| Divorced/unmarried | 7 | 21 | ||

| Employment | 0.591 | |||

| Employed | 7 | 12 | ||

| Retired | 28 | 37 | ||

| BMI | 0.787 | |||

| ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 8 | 10 | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 27 | 39 | ||

| Smoking history | 0.675 | |||

| With | 25 | 37 | ||

| Without | 10 | 12 | ||

| History of alcoholism | 0.454 | |||

| With | 4 | 9 | ||

| Without | 31 | 40 | ||

| Hypertension | 0.556 | |||

| With | 5 | 10 | ||

| Without | 30 | 39 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.446 | |||

| With | 6 | 12 | ||

| Without | 29 | 37 | ||

| Castration scheme | 0.003b | |||

| Surgery | 21 | 14 | ||

| Medication | 14 | 35 | ||

| Monthly income | 0.010a | |||

| ≥ 4500 RMB | 8 | 25 | ||

| < 4500 RMB | 27 | 24 | ||

| Postoperative VAS score | 0.007a | |||

| ≥ 5 points | 13 | 6 | ||

| < 5 points | 22 | 43 |

According to the results, we assigned values to marital status, castration scheme, monthly income, and postoperative VAS score (Table 3). Then, multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the independent factors for patients' negative mood. Marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative VAS score were identified as independent risk factors for adverse mood (Table 4; P < 0.05).

| Factors | Assignment |

| Marital status | Married = 1; unmarried/divorced = 0 |

| Castration scheme | Surgery = 1; medication = 0 |

| Monthly income | ≥ 4500 RMB = 0; < 4500 RMB = 1 |

| Postoperative VAS score | ≥ 5 points = 1; < 5 points = 0 |

| Bad mood | Bad mood = 1; emotional stability = 0 |

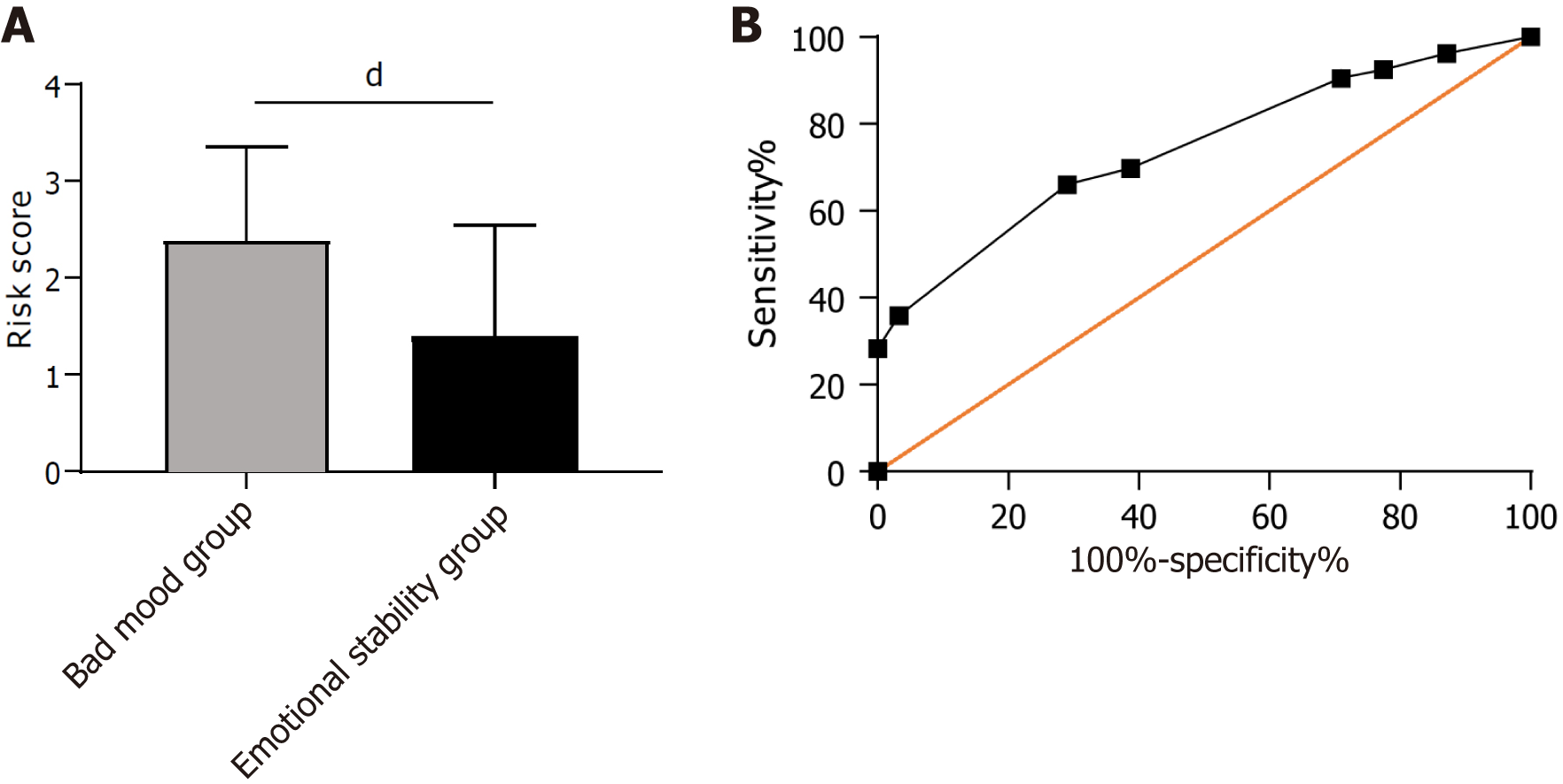

Based on the β coefficient of logistic regression, we constructed a risk scoring formula: 1.284* marital status + 1.224* castration scheme + 1.792* postoperative VAS score. By calculating the risk score of each patient, we found that the risk score of patients in the bad mood group was significantly higher than that of patients in the emotional stability group (P < 0.0001; Figure 2). Moreover, ROC curve analysis showed that the AUC of the risk prediction model for predicting patients' bad mood was 0.743, the specificity was 70.96%, and the sensitivity was 66.03%.

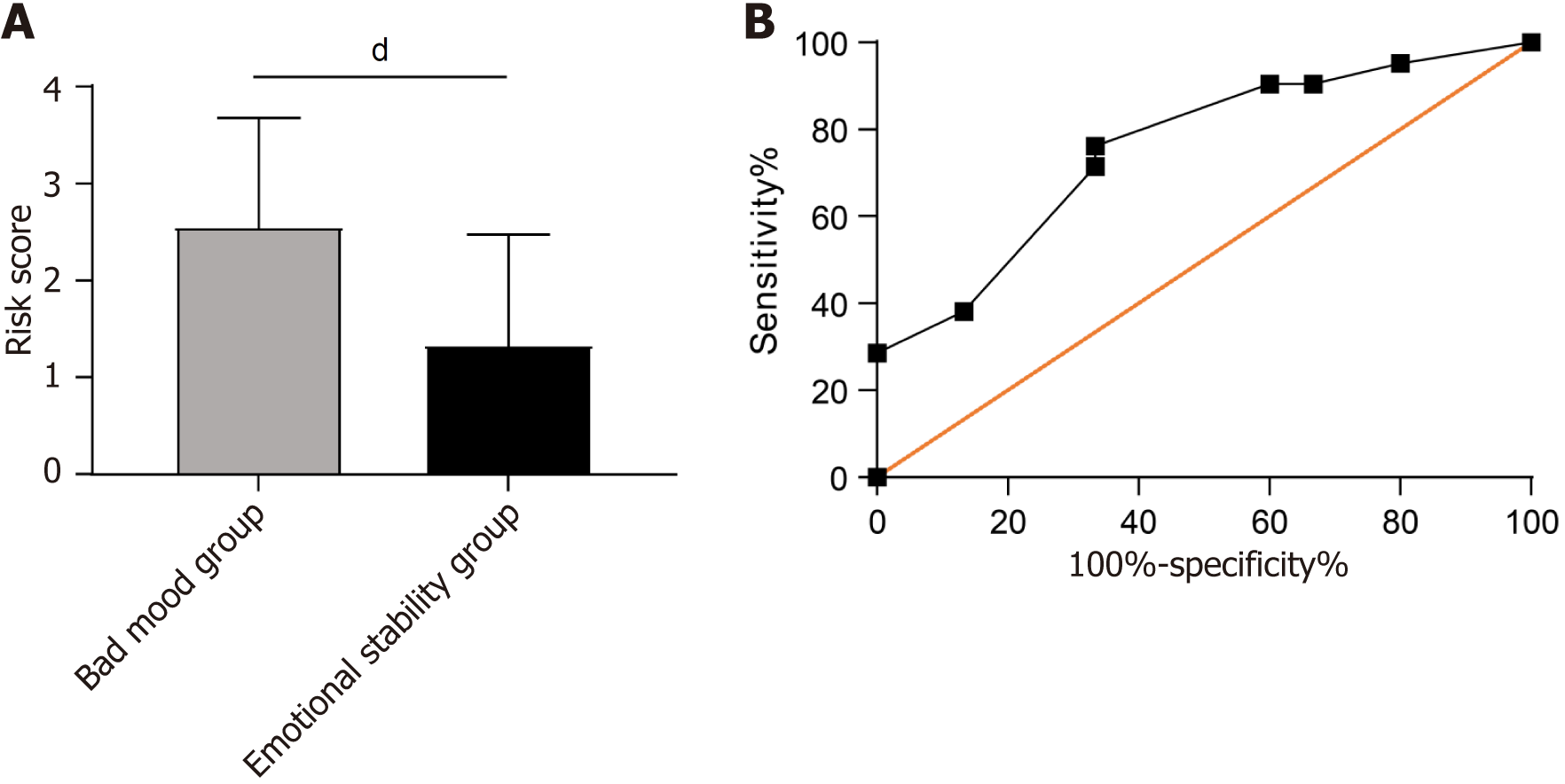

There were 15 patients in the validation group with adverse emotions. According to the risk scoring formula, we substituted the clinical data of the validation group into the formula for calculation and found that the risk score of patients with bad mood in the validation group was significantly higher than that of patients in the emotional stability group (P < 0.0001; Figure 3 and Table 5). Through ROC curve analysis, the AUC, specificity, and sensitivity of the risk prediction model for the prediction of adverse mood in the validation group were 0.755, 66.67%, and 76.19%, respectively.

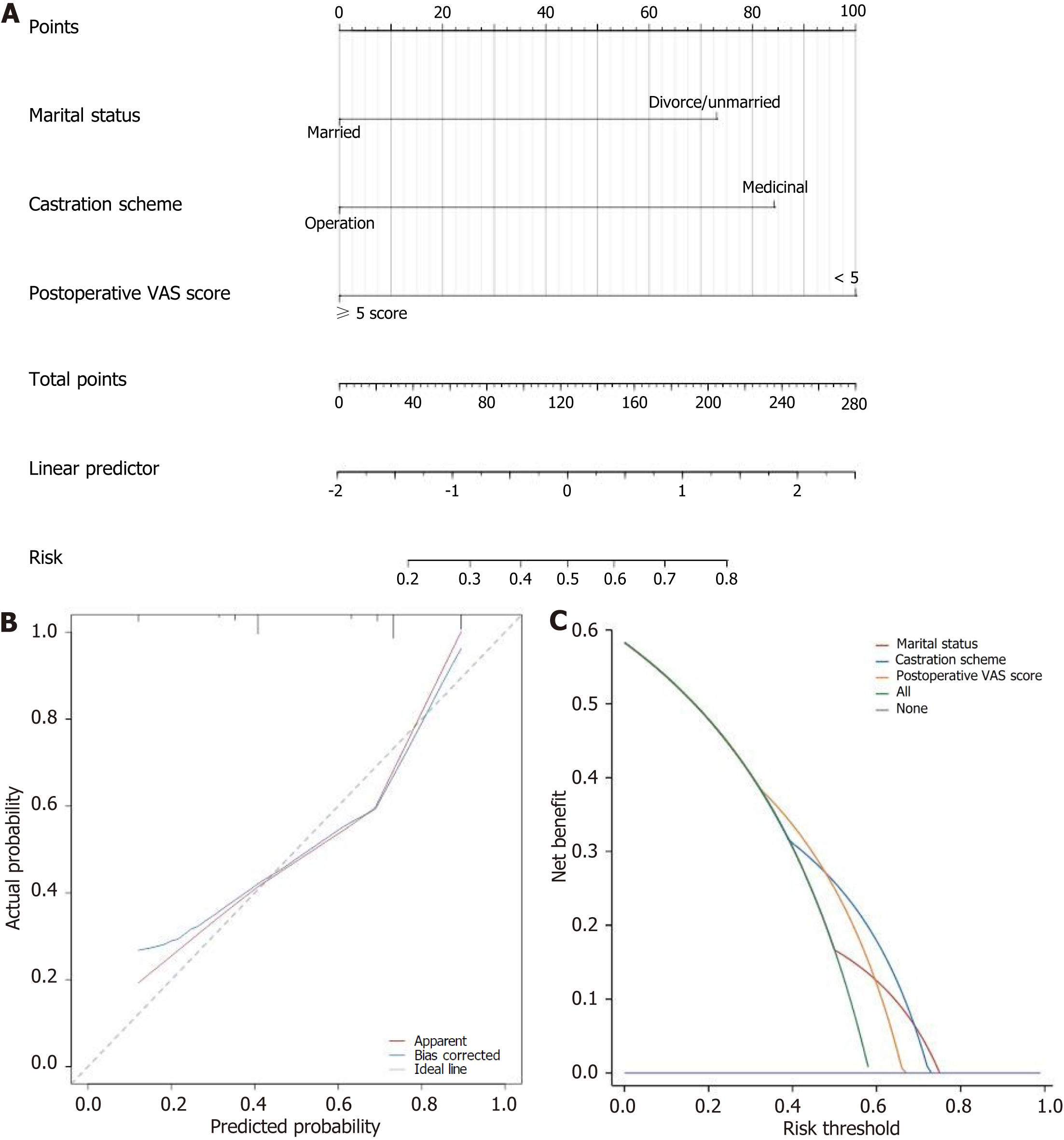

The three independent risk factors were used to establish a nomogram for the prediction of bad mood in PC patients (Figure 4). The corresponding score was given to each indicator, depending on the specific condition, and the total score, and the scores were added together to obtain the total score. A vertical line from the total score to the probability axis of bad mood risk was the occurrence risk of bad mood. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test revealed a χ2 value of 4.2856, a P value of 0.830, and a C-index of 0.773 (0.692-0.854). The calibration curve showed basic consistency between the predicted and actual curves (Figure 4), indicating that the model had good discrimination and accuracy. The analysis of the decision curve revealed that the model had a high net benefit (Figure 4).

Cancer-related anxiety and depression are common clinical reactions to serious psychophysiological stress. The incidence of anxiety and depression varies among patients with different types of cancer[14]. This study found that the incidence rates of anxiety and depression in PC patients were 41.66% and 44.04%, respectively, which is basically consistent with foreign research[15,16]. Most PC patients in China have progressed to the middle and late stages upon diagnosis, which is unsuitable for radical surgery. Meanwhile, they are often complicated with physical pain and bone metastasis, which can impose heavy physical and mental burdens on them[17,18]. Therefore, during PC treatment, we should not only pay attention to physical adverse events but also attach sufficient importance to the occurrence of adverse psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression to improve patient prognosis.

In this study, we analyzed the risk factors for postoperative anxiety and depression in PC patients undergoing surgical castration. Marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative VAS score were identified as important factors affecting postoperative anxiety and depression. In addition, research has found that widowed men have a higher risk of developing PC than those who are married or in a relationship. This may mean that social support in marriage or partnership may help to promote a healthy lifestyle and active attention to medical care, which in turn affects PC risk and prognosis. We believe that castration treatment of PC, especially surgical castration, can cause a sharp drop in male hormone levels in physiological terms, which is a possible cause of the above effects. The testicles are the organs that primarily produce male hormones such as testosterone, which play an important role in regulating mood and psychological state. After surgical castration, male patients may experience a physiological reaction of decreased testosterone levels, which will lead to emotional changes such as mood swings, anxiety, and depression. Such a physiological change may trigger physical and psychological discomfort, including mood swings, insomnia and fatigue, contributing to anxiety and depression. In addition, castration treatment may lead to sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction and decreased libido, all of which may adversely influence patients' self-esteem and self-confidence, triggering anxiety and depression. Furthermore, castration therapy can cause changes that affect a patient's body image, such as weight gain and breast hypertrophy, which may affect one's feelings of self-image and self-identity, leading to anxiety and depression. Somatic pain seriously affects the quality of daily life of PC patients, and the stress response triggered by pain may induce anxiety and depression. Moreover, patients undergoing surgical castration are affected by the operation, which increases the stress of the body.

By collecting and analyzing relevant clinical features and predictive variables, regression models can be used to predict the probability or risk of a specific event. These events may include disease development, therapeutic response, complications, disease risk assessment, personalized medicine, screening and early intervention, and decision support. The logistic regression model is a regression model for establishing binary classification problems, which is suitable for continuous and discrete features due to the advantages of interpretability, probability prediction, simplicity, and efficiency. This model is widely used in various practical applications, helping to estimate the probability of binary outcome variables and providing an explanation of the degree of influence of features on target variables. Through the establishment of a logistic regression model, we found that the risk score constructed based on marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative VAS score successfully predicted the occurrence of bad mood in PC patients after castration treatment with an AUC of 0.743. In addition, through data validation, the AUC of the model for predicting bad mood in validation group patients was found to be 0.755, indicating the high generalization potential of the model. Based on the results of multivariate analysis, the nomograph integrates multiple clinically relevant variables into line segments with scales, visualizing and graphically presenting the influence of each variable on clinical outcomes, which makes it easy and intuitive to be applied in hospitals for calculating clinical outcome probabilities. At the end of the study, we drew a nomogram and found through the calibration curve that the predicted curve was basically consistent with the actual curve. Furthermore, the decision curve revealed a high net benefit of the model, suggesting good prediction efficiency; this implies that it will be helpful for medical staff in predicting the adverse emotion risk of PC patients individually and accurately.

Although this study identified the risk factors for the occurrence of bad mood in PC patients after castration treatment, there are still some limitations. First, since we did not collect the prognostic data of patients, more data are needed to support the analysis of the impact of bad mood on patients' long-term outcomes. Second, the sample size is small, and whether this will lead to bias in the data analysis needs further exploration. Finally, as this is a single-center study, more data are needed to verify the feasibility of the model for generalization in other centers. Therefore, we hope to cooperate in follow-up research and collect more data to validate our model.

In patients with PC, marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative pain (VAS) score are important factors affecting postoperative anxiety and depression. A logistic regression model can be used to successfully predict the risk of adverse psychological emotions. Through an individualized risk assessment, health care professionals can intervene in advance to improve patients' mental health and outcomes. However, further validation and sample size extension are needed to deepen the understanding of the psychological problems of PC patients and to look for other possible influencing factors that may provide more precise intervention strategies and support measures.

Cancer-related anxiety and depression are common severe psychological stress reactions in clinical practice, with their incidence rates varying among patients with different types of cancer. Prostate cancer (PC), a common type of cancer that is usually diagnosed in the advanced stages, makes radical surgery impossible. In addition, the disease is accompanied by complications such as physical pain and bone metastasis, which brings a heavy physical and mental burden to patients. Therefore, in the clinical treatment of PC, we should pay attention to not only the adverse reactions of the body, but also the occurrence of psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression, so as to improve the prognosis of patients.

The motivation for this study is to understand the factors that influence postoperative anxiety and depression in PC patients, based on which healthcare professionals can develop effective intervention and support strategies to meet the mental health needs of these patients.

The objective of this study is to analyze the risk factors affecting postoperative anxiety and depression in PC patients, and to explore the effects of marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative Visual Analogue Scale (VAS score) on anxiety and depression. In addition, the study aims to establish a prediction model using logistic regression analysis to evaluate the risk of adverse emotional outcomes of these patients.

In this study, retrospective analysis was used to investigate the relationship between various clinical factors and postoperative anxiety and depression in PC patients. Data such as marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative VAS score were collected and analyzed. Using the logistic regression model, a risk scoring system was developed to predict the occurrence of adverse emotional outcomes.

Marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative VAS score were identified to be important factors affecting postoperative anxiety and depression in PC patients. The logistic regression model successfully predicted the risk of adverse emotional outcomes, with an area under the curve of 0.743. The model exhibited high generalization with a verified area under the curve of 0.755.

The findings highlight the importance of psychological symptoms, especially anxiety and depression, in the clinical management of patients with PC. Marital status, castration scheme, and postoperative VAS score are identified as important predictors of adverse emotional outcomes. The logistic regression model shows good accuracy, which is helpful to individualize and improve the predictive ability of psychological risk in PC patients.

Although this study successfully identified the risk factors and developed a risk prediction model, there are still some limitations. Further research is needed to explore the long-term outcomes of patients and the impact of adverse emotional outcomes on patient prognosis, and to validate the generalization of the model with more data. Future research collaborations and data collection are important to further understand and apply this predictive model in PC.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pak H, Turkey; Sunanda T, United States S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Desai K, McManus JM, Sharifi N. Hormonal Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Endocr Rev. 2021;42:354-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sekhoacha M, Riet K, Motloung P, Gumenku L, Adegoke A, Mashele S. Prostate Cancer Review: Genetics, Diagnosis, Treatment Options, and Alternative Approaches. Molecules. 2022;27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 131.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang G, Zhao D, Spring DJ, DePinho RA. Genetics and biology of prostate cancer. Genes Dev. 2018;32:1105-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 72.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu J, Dong L, Zhu Y, Dong B, Sha J, Zhu HH, Pan J, Xue W. Prostate cancer treatment - China's perspective. Cancer Lett. 2022;550:215927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Teo MY, Rathkopf DE, Kantoff P. Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70:479-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 79.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Menges D, Yebyo HG, Sivec-Muniz S, Haile SR, Barbier MC, Tomonaga Y, Schwenkglenks M, Puhan MA. Treatments for Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: Systematic Review, Network Meta-analysis, and Benefit-harm assessment. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5:605-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boevé LMS, Hulshof MCCM, Vis AN, Zwinderman AH, Twisk JWR, Witjes WPJ, Delaere KPJ, Moorselaar RJAV, Verhagen PCMS, van Andel G. Effect on Survival of Androgen Deprivation Therapy Alone Compared to Androgen Deprivation Therapy Combined with Concurrent Radiation Therapy to the Prostate in Patients with Primary Bone Metastatic Prostate Cancer in a Prospective Randomised Clinical Trial: Data from the HORRAD Trial. Eur Urol. 2019;75:410-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Naser AY, Hameed AN, Mustafa N, Alwafi H, Dahmash EZ, Alyami HS, Khalil H. Depression and Anxiety in Patients With Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychol. 2021;12:585534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang YH, Li JQ, Shi JF, Que JY, Liu JJ, Lappin JM, Leung J, Ravindran AV, Chen WQ, Qiao YL, Shi J, Lu L, Bao YP. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1487-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 86.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Charalambous A, Giannakopoulou M, Bozas E, Paikousis L. Parallel and serial mediation analysis between pain, anxiety, depression, fatigue and nausea, vomiting and retching within a randomised controlled trial in patients with breast and prostate cancer. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Duarte V, Araújo N, Lopes C, Costa A, Ferreira A, Carneiro F, Oliveira J, Braga I, Morais S, Pacheco-Figueiredo L, Ruano L, Tedim Cruz V, Pereira S, Lunet N. Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Prostate Cancer, at Cancer Diagnosis and after a One-Year Follow-Up. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nissen ER, O'Connor M, Kaldo V, Højris I, Borre M, Zachariae R, Mehlsen M. Internet-delivered mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression in cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2020;29:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yue T, Li Q, Wang R, Liu Z, Guo M, Bai F, Zhang Z, Wang W, Cheng Y, Wang H. Comparison of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Zung Self-Rating Anxiety/Depression Scale (SAS/SDS) in Evaluating Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. Dermatology. 2020;236:170-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Irusen H, Fernandez P, Van der Merwe A, Suliman S, Esterhuizen T, Lazarus J, Parkes J, Seedat S. Depression, Anxiety, and Their Association to Health-Related Quality of Life in Men Commencing Prostate Cancer Treatment at Tertiary Hospitals in Cape Town, South Africa. Cancer Control. 2022;29:10732748221125561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Huang T, Su H, Zhang S, Huang Y. Reminiscence therapy-based care program serves as an optional nursing modality in alleviating anxiety and depression, improving quality of life in surgical prostate cancer patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54:2467-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kaushik D, Shah PK, Mukherjee N, Ji N, Dursun F, Kumar AP, Thompson IM Jr, Mansour AM, Jha R, Yang X, Wang H, Darby N, Ricardo Rivero J, Svatek RS, Liss MA. Effects of yoga in men with prostate cancer on quality of life and immune response: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Conant KJ, Huynh HN, Chan J, Le J, Yee MJ, Anderson DJ, Kaye AD, Miller BC, Drinkard JD, Cornett EM, Gomelsky A, Urits I. Racial Disparities and Mental Health Effects Within Prostate Cancer. Health Psychol Res. 2022;10:39654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Popiołek A, Brzoszczyk B, Jarzemski P, Piskunowicz M, Jarzemski M, Borkowska A, Bieliński M. Quality of Life of Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Prostatectomy and Affective Temperament. Cancer Manag Res. 2022;14:1743-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |