Published online Feb 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.245

Peer-review started: November 14, 2023

First decision: December 7, 2023

Revised: December 14, 2023

Accepted: January 8, 2024

Article in press: January 8, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2024

Processing time: 83 Days and 17.9 Hours

Many studies have explored the relationship between depression and metabolic syndrome (MetS), especially in older people. China has entered an aging society. However, there are still few studies on the elderly in Chinese communities.

To investigate the incidence and risk factors of depression in MetS patients in mainland China and to construct a predictive model.

Data from four waves of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study were selected, and middle-aged and elderly patients with MetS (n = 2533) were included based on the first wave. According to the center for epidemiological survey-depression scale (CESD), participants with MetS were divided into depression (n = 938) and non-depression groups (n = 1595), and factors related to depression were screened out. Subsequently, the 2-, 4-, and 7-year follow-up data were analyzed, and a prediction model for depression in MetS patients was constructed.

The prevalence of depression in middle-aged and elderly patients with MetS was 37.02%. The prevalence of depression at the 2-, 4-, and 7-year follow-up was 29.55%, 34.53%, and 38.15%, respectively. The prediction model, constructed using baseline CESD and Physical Self-Maintenance Scale scores, average sleep duration, number of chronic diseases, age, and weight had a good predictive effect on the risk of depression in MetS patients at the 2-year follow-up (area under the curve = 0.775, 95% confidence interval: 0.750-0.800, P < 0.001), with a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 74%.

The prevalence of depression in middle-aged and elderly patients with MetS has increased over time. The early identification of and intervention for depressive symptoms requires greater attention in MetS patients.

Core Tip: In this study, a 7-year follow-up of middle-aged and elderly people in China Mainland was conducted, and it was found that the incidence of depression increased in the population of metabolic syndrome.

- Citation: Zhou LN, Ma XC, Wang W. Incidence and risk factors of depression in patients with metabolic syndrome. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(2): 245-254

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i2/245.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.245

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a pathological condition characterized by abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, hyper-tension, and hyperlipidemia[1]. MetS has become a global problem; although its prevalence varies according to different diagnostic criteria, a high prevalence of MetS is undeniable. A cross-sectional study in China reported a MetS prevalence of 14.39%, according to diagnostic criteria defined by the Chinese Diabetes Society[2]. Another meta-analysis reported a prevalence of approximately 15.5% in China[3]. MetS is more common in the elderly[4], as it causes diabetes, stroke, and cognitive impairment, posing a serious disease burden to the middle-aged and the elderly populations[5].

MetS is also common in individuals with psychiatric disorders[6], including bipolar disorder[7], schizophrenia[8], depression[9], dementia[10], and other psychiatric disorders[11]. Moreover, MetS is becoming more common in young people with depression[9]. However, this phenomenon has received insufficient attention. This suggests that although MetS is a disease with age-related morbidity, there is still a need to focus on age groups other than the elderly, especially when there is comorbidity with psychiatric disorders.

Depression is also a disease that cannot be ignored in the elderly population. Our previous study, as well as those of others, have reported a high prevalence of depression in middle-aged and older adults[12,13], leading to significant effects on individual medical expenses[14]. As shown above, both depression and MetS have a high incidence and heavy burden in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Therefore, more attention should be paid to depression and MetS in middle-aged and elderly individuals.

Additionally, a bidirectional relationship seems to exist between depression and MetS[15], and this association is even stronger in older people[16]. On the one hand, elderly patients with MetS have a higher prevalence of depression than the general population[17]. The more MetS components the patients have, the more severe their depressive symptoms are[18]. On the other hand, elderly patients with depression also have a higher prevalence of MetS[19]. Low levels of inflammation, low levels of activity, and antidepressant use in depression patients contribute to the development of MetS[20-22], and may lead to a risk of fatalities[23]. This may be related to the fact that depression and MetS share some pathogenic factors, such as chronic low-grade inflammation[24], and the dysregulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, the autonomic nervous system, the immune system, and platelet and endothelial function[25]. However, other studies have denied a link between depression and MetS[26,27], or have simply highlighted the association between atypical depression and MetS[28].

Overall, the relationship between depression and MetS remains unclear. Large population and cohort studies need to be supplemented to analyze the association between depression and MetS, as well as the complex influencing factors. Therefore, based on a large community-based cohort study conducted in mainland China, we designed this study to investigate the incidence and risk factors of depression in MetS patients and to construct a predictive model.

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) is a survey conducted in the Chinese mainland. The survey participants were those in the community who were 45 years old and above. The main contents include demographics, health, function, insurance, work, retirement, and physical examination. CHARLS has been conducting baseline surveys since 2011 and has published data from four surveys. Details such as design and sampling have been covered in previous studies[29,30]. The national baseline survey conducted during 2011-2012 consisted of 17708 individuals. The second wave was conducted in 2013-2014 for a 2-year follow-up period, and 15628 individuals were successfully re-interviewed. In 2015-2016, 14555 individuals enrolled at baseline were re-interviewed for the third wave at the 4-year follow-up. The fourth wave survey-the most recent survey-conducted in 2018-2019, included 19744 participants who participated in their 7-year follow-up.

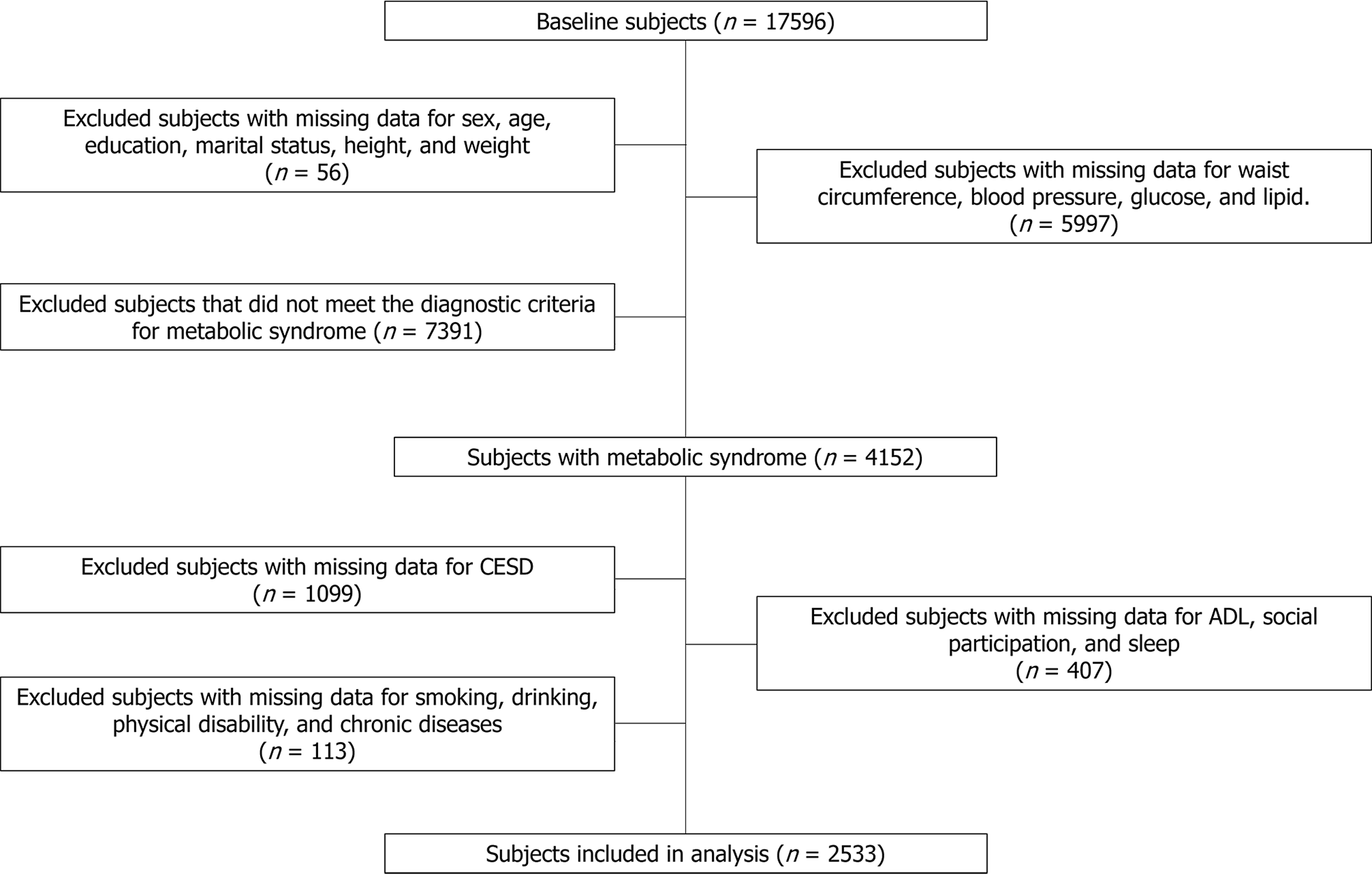

Based on the survey data from 2011 as the baseline, participants were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) Meeting the diagnostic criteria for MetS; (2) center for epidemiological survey-depression scale (CESD) score, and (3) complete demographic data, health-related data, activities of daily living (ADL), social participation, etc. Based on the above criteria, 2533 patients were selected at baseline. Second, patients’ 2-, 4-, and 7-year follow-up information was analyzed. A screening flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

According to Zhu et al[31], the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) definition is more pertinent than the Adult Treatment Panel III definition for screening and estimating the risk of cerebrovascular disease and diabetes in Asian American adults. Therefore, in this study, the IDF definition was selected as the diagnostic criteria for MetS, and patients were required to have at least two of the following four conditions on the basis of abdominal obesity: (1) High triglyceride (TG) level: ≥ 150 mg/dL (≥ 1.69 mmol/L); (2) reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level: < 40 mg/dL (< 1.03 mmol/L) for men, < 50 mg/dL (< 1.29 mmol/L) for women; (3) high blood pressure: ≥ 130 mmHg systolic blood pressure, ≥ 85 mmHg diastolic blood pressure (DBP), or receipt of antihypertensive medication, and (4) high fasting glucose [≥ 100 mg/dL (≥ 5.56 mmol/L)] or diabetes diagnosis. Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference ≥ 90 cm in men and ≥ 80 cm in women.

The CESD is a widely used depression assessment scale used in epidemiological surveys. The CESD comprises 10 items, and each question has a 4-level rating, respectively No, I don’t have any difficulty; I have difficulty but can still do it; Yes, I have difficulty and need help; and I cannot do it. Scores of 0-3 are assigned, respectively, two of which are reverse grades. The total score is added to obtain the CESD score. The CESD has been used in a large-scale population survey in mainland China, with certain validity and reliability[32]. In this study, we labeled CESD ≥ 10 symptomatic depression, referred to as depression group, according to the criteria of Andresen et al[33]. And participants with CESD < 10 were defined as the non-depressed group.

The ADL was measure via the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (PSMS) and Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL)[34]. In this study, the PSMS included whether and how difficult it was to jog, walk, climb stairs, bend, and lift heavy objects, while the IADL included housekeeping, preparing meals, shopping, paying, and taking medications. The choices are on a 4-point scale, and they are No, I don’t have any difficulty; I have difficulty but can still do it; yes, I have difficulty and need help; and I cannot do it. A score of 1 to 4 points was assigned. The higher the total score, the more severely affected the individuals’ health status.

The CHARLS investigated the type and frequency of social participation among middle-aged and elderly people. The types of social participation include: (1) Interacting with friends; (2) playing Ma-Jong, playing chess, playing cards, or attending a community club; (3) providing help to family, friends, or neighbors who do not live with you and who did not pay you for the help; (4) going to a sport, social, or other kind of club; (5) taking part in a community-related organization; (6) doing voluntary or charity work; (7) caring for a sick or disabled adult who does not live with you and who did not pay you for the help; (8) attending an educational or training course; (9) stock investment; (10) using the Internet; (11) other, and (12) none of these. They were then asked, regarding each of the selected activities: “How often have you done these social activities in the past month?” Respondents were asked to select the choice that best suited their situation from “almost every day”; “almost every week”; and “not often”. We chose the frequency of activities with the highest participation as the frequency of social participation.

Physical examinations included height, weight, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, DBP, sleep, chronic diseases, and biomarkers. The sleep aspect included a survey of the average sleep duration and nap time. The collection of blood samples required the respondents to fast for one night, and three tubes of venous blood were collected from each respondent by medically trained staff from the China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), based on a standard protocol. After collection, these fresh venous blood samples were transported at 4 ℃, to either local CDC laboratories or township-level hospitals near the study sites, or transported to the China CDC in Beijing within 2 wk for further testing. The biomarkers tested included white blood cell count (WBC), HDL, C-reactive protein (CRP), TG, fasting blood glucose (FBG), and uric acid (UA).

All the data in this study were imported into SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) for analysis. First, we described the overall data and divided the patients into a depression group and a non-depression group, according to whether they met the criteria of symptomatic depression at baseline, and compared the overall data of the two groups at baseline. In this part of the results, categorical variables were expressed as N (%), the chi-squared test was used to compare the differences between the two groups, continuous variables were expressed as the mean [95% confidence interval (CI)], and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to compare the two groups.

To determine which factors were associated with depression in MetS patients, we performed regression analyses on baseline data. Variables with P < 0.1 in the comparison of the two groups were screened and included in multivariate regression analysis, with the CESD score as the dependent variable. Subsequently, we performed multiple regression analyses with significant variables obtained from multivariate regression and the CESD score at baseline as independent variables, and the CESD score at follow-up as dependent variables to screen for the factors related to symptomatic depression in MetS patients.

Finally, we used Cox regression to construct a predictive model of depression in MetS patients, with variables with P < 0.1 and the CESD score at baseline as independent variables, and the occurrence of depression as the outcome variable. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all statistical analyses.

In this study, 1595 cases in the non-depression group and 938 cases in the depression group were included, and the prevalence of depression in MetS patients was 37.02%. The detailed data are shown in Table 1.

| Non-depression (n = 1595) | Depression (n = 938) | P value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 552 (34.61) | 209 (22.28) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 1043 (65.39) | 729 (77.72) | |

| Age, yr | 58.34 (57.90, 58.78) | 60.23 (59.65, 60.81) | < 0.001 |

| Education | |||

| 0 yr | 403 (25.27) | 352 (37.53) | < 0.001 |

| 1-6 yr | 612 (38.37) | 394 (42.00) | |

| 7-12 yr | 547 (34.29) | 183 (19.51) | |

| > 12 yr | 33 (2.07) | 9 (0.96) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 1457 (91.35) | 783 (83.48) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 138 (8.65) | 155 (16.52) | |

| Physical disability | |||

| Yes | 185 (11.60) | 186 (19.83) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1410 (88.40) | 752 (80.17) | |

| Number of chronic diseases | 1.53 (1.46, 1.59) | 2.18 (2.08, 2.29) | < 0.001 |

| Height, cm | 158.42 (157.98, 158.86) | 155.53 (155.03, 156.02) | < 0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 66.76 (66.15, 67.26) | 63.51 (62.79, 64.24) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 469 (29.40) | 719 (76.65) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1126 (70.60) | 219 (23.35) | |

| Drinking | |||

| Yes | 314 (19.69) | 108 (11.51) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1281 (80.31) | 830 (88.49) | |

| WBC, 109/L | 6.312 (6.215, 6.410) | 6.388 (6.250, 6.527) | 0.911 |

| CRP, mg/L | 3.20 (2.82, 3.58) | 3.27 (2.77, 3.78) | 0.864 |

| UA, mg/dL | 4.67 (4.61, 4.74) | 4,43 (4.35, 4.50) | < 0.001 |

| CESD | 4.63 (4.49, 4.76) | 14.77 (14.50, 15.05) | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 94.21 (93.83, 94.59) | 93.28 (92.79, 93.76) | 0.522 |

| TG, mg/dL | 193.58 (185.88, 201.29) | 184.17 (175.75, 192.60) | 0.266 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 41.80 (41.21, 42.39) | 42.84 (42.09, 43.60) | 0.020 |

| SBP, mmHg | 111.94 (111.16, 112.72) | 112.92 (111.88, 113.96) | 0.163 |

| DBP, mmHg | 80.40 (79.78, 81.02) | 79.89 (79.10, 80.68) | 0.359 |

| Glu, mg/dL | 122.19 (119.81, 124.57) | 120.95 (117.97, 123.93) | 0.522 |

| Average sleep duration, hour | 6.72 (6.64, 6.79) | 5.77 (5.64, 5.90) | < 0.001 |

| Nap time, minutes | 36.52 (34.32, 38.73) | 31.87 (29.20, 34.54) | 0.009 |

| Social participation | |||

| Types of activities | 0.88 (0.84, 0.93) | 0.67 (0.62, 0.73) | < 0.001 |

| Frequency of activities | 1.65 (1.55, 1.75) | 1.29 (1.17, 1.42) | < 0.001 |

| PSMS | 11.69 (11.53, 11.85) | 15.26 (14.95, 15.58) | < 0.001 |

| IADL | 5.36 (5.29, 5.42) | 6.58 (6.40, 6.77) | < 0.001 |

Demographic information: There were significant differences in sex, age, education, and marital status between the two groups (P < 0.001). Specifically, women, younger ages, lower levels of education, and single people were overrepresented in the depression group.

Health information: Compared to the non-depression group, participants in the depression group had lower height and weight, more physical disabilities and chronic diseases, more smoking and drinking, and less average sleep and nap time (P < 0.05).

Physical examination: The depression group had lower serum UA and higher HDL levels (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in WBC, CRP, TG, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, DBP, or FBG between the two groups (P > 0.05).

ADL and social participation: The types and frequencies of social participation activities in the depression group were significantly lower than those in the control group, and the scores of PSMS and IADL were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.001).

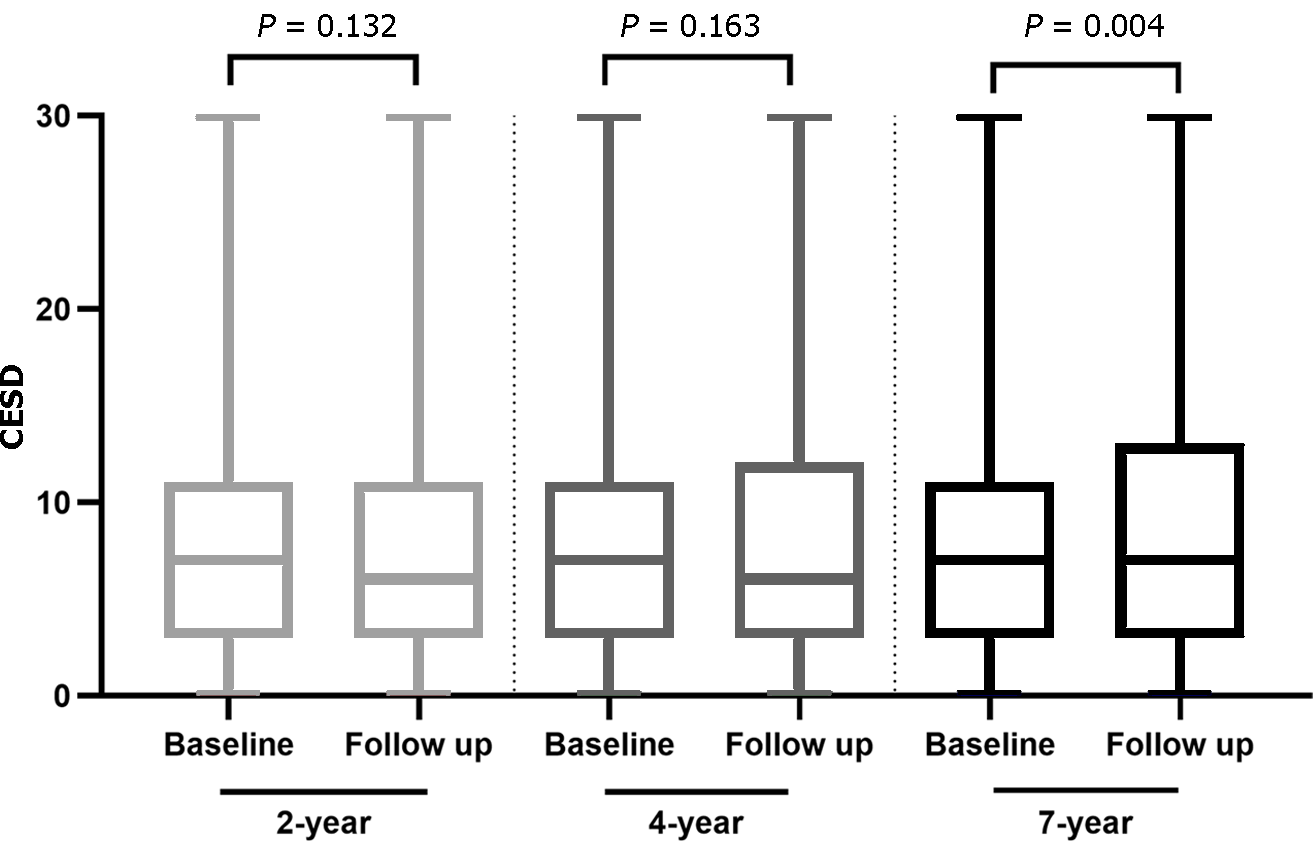

Two-year follow-up: During the 2-year follow-up, 929 patients were lost to follow-up or died, and the remaining 1604 patients were followed up. Their average CESD score was 7.59 (95%CI: 7.30-7.88). Among this group, 474 patients (29.55%) had depression. Compared with the baseline, the CESD score did not significantly increase or decrease (P = 0.132, Figure 2), and 181 cases (17.01%, 181/1064) newly developed depression.

Four-year follow-up: During the 4-year follow-up, compared with the baseline, 998 cases were lost to follow-up or died, 1535 cases remained with an average CESD score of 8.16 (95%CI: 7.71-8.30), and 530 cases had depression, accounting for 34.53% of the cohort. There were no significant differences in CESD scores from the baseline (P = 0.163, Figure 2), and 239 cases (23.62%, 239/1,012) had newly developed depression.

Seven-year follow-up: During the 7-year follow-up, compared with the baseline period, 1,196 patients were lost to follow-up or died, and the remaining 1337 patients had an average CESD score of 8.67 (95%CI: 8.31-9.02). Compared with baseline, the CESD score was significantly increased (P = 0.004, Figure 2). A total of 510 patients (38.15%) had depression. There were 243 new cases of depression, accounting for 26.85% of the cohort (243/905).

During the overall follow-up, 1,186 patients completed the follow-up. Among them, 462 patients (38.95%) were newly diagnosed with depression, and the average time required for depression to manifest was (4.000 ± 1.978) years.

Factors associated with CESD at baseline: Multivariable logistic regression analysis with baseline CESD score as the dependent variable showed that CESD at baseline was associated with PSMS, IADL, average sleep duration, marital status, number of chronic diseases, age, and weight (Table 2, P < 0.05).

Factors associated with CESD at follow-up: The multivariable logistic regression analysis with CESD score in the follow-up period as the dependent variable found that CESD score at the 2-year follow-up was associated with baseline CESD score, PSMS, average sleep duration, number of chronic diseases, age, and weight. CESD score at the 4-year follow-up was associated with baseline CESD, ADL, and weight, while CESD score at the 7-year follow-up was associated with baseline CESD, ADL, average sleep duration, age, and weight. The detailed data are shown in Table 2.

| Baseline | 2-yr follow up | 4-yr follow up | 7-yr follow up | |||||

| Variables | OR (95%CI) | Beta | OR (95%CI) | Beta | OR (95%CI) | Beta | OR (95%CI) | Beta |

| Age | -0.551 (-0.816, -0.286) | -0.075 | -0.056 (-0.086, -0.026) | -0.081 | - | -0.052 (-0.093, -0.011) | -0.063 | |

| Marital status | 1.893 (1.253, 2.533) | 0.102 | - | - | - | |||

| Height | 0.246 (0.016, 0.475) | 0.084 | -0.054 (-0.076, -0.031) | -0.103 | -0.047 (-0.073, -0.021) | -0.082 | -0.054 (-0.083, -0.025) | -0.092 |

| Number of chronic diseases | 0.448 (0.310, 0.586) | 0.113 | 0.211 (0.039, 0.383) | 0.055 | - | - | ||

| Average sleep duration | -0.664 (-0.771, -0.558) | -0.205 | -0.265 (-0.406, -0.124) | -0.081 | - | -0.410 (-0.596, -0.224) | -0.110 | |

| PSMS | 0.46 (0.402, 0.518) | 0.333 | 0.174 (0.103, 0.246) | 0.120 | 0.177 (0.095, 0.258) | 0.109 | 0.166 (0.069, 0.263) | 0.094 |

| IADL | 0.293 (0.184, 0.402) | 0.105 | - | - | - | |||

| Baseline CESD | - | 0.424 (0.376, 0.472) | 0.424 | 0.450 (0.393, 0.506) | 0.407 | 0.414 (0.349, 0.478) | 0.359 | |

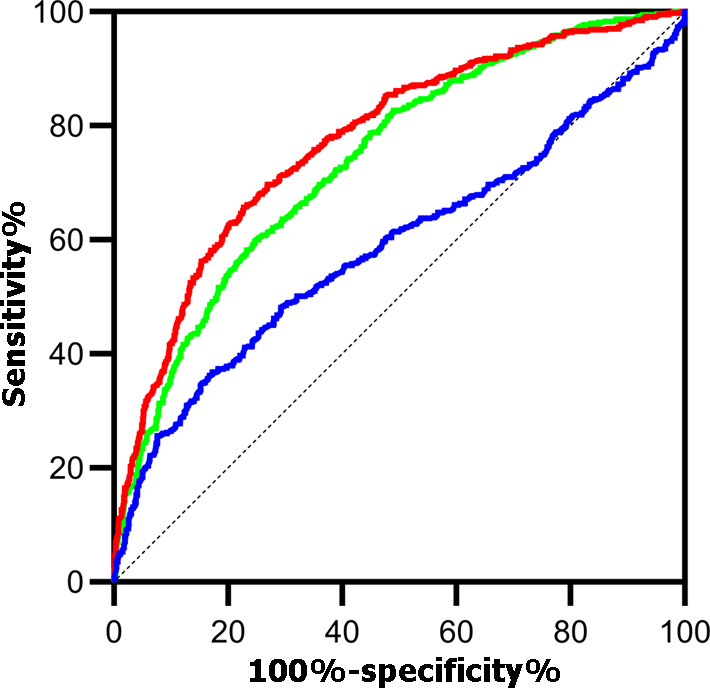

These factors were used as independent variables to construct the CESD prediction model during the follow-up period. The results showed that the CESD prediction model constructed during the 2-year follow-up period had a better predictive ability than other follow-up periods [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.775, 95%CI: 0.750-0.800, P < 0.001], with a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 74% (Figure 3).

Factors associated with new onset depression: Cox regression analysis showed that age [odds ratio (OR) = 0.986, 95%CI: 0.978-0.993], weight (OR = 0.487, 95%CI: 0.421-0.564), average sleep duration (OR = 0.926, 95%CI: 0.894-0.959), and ADL (OR = 1.042, 95%CI: 1.026-1.058) were associated with symptomatic depression in MetS patients within 7 years of follow-up (all P < 0.001).

The bidirectional relationship between depression and MetS remains questionable, especially in middle-aged and older adults, who have high rates of both conditions. This study focused on middle-aged and elderly patients with MetS in mainland China and followed them for 7 years to screen for risk factors associated with depression in MetS patients. We compared the information of people with depression and those without depression among MetS patients at baseline and found many differences, such as that those with MetS and depression included more women, lower education level, more single people, lower height and weight, more physical disabilities, more chronic diseases, more smoking and drinking, less average sleep and nap time, less frequency of social participation, impaired ability of daily living, etc[13,35-38]. These are all features of depression that have been reported in previous studies. However, we found that people with depression and MetS were younger than those without depression, which is related to the younger age of the current depressed population. On the one hand, the onset of depression tends to be younger, and on the other hand, a meta-analysis of observational studies found that depressive participants under 50 years of age were more likely to develop MetS than those over 50 years[34], and concluded that the odds of MetS in depressive patients decreased with age. These results suggest that the mutual worsening of MetS and depression is more significant in younger adults.

We then analyzed the follow-up data and selected the follow-up time points of 2, 4, and 7 years. It was found that the depression score at the 7-year follow-up was significantly higher than that of the baseline period, the prevalence of depression reached 38.15%, and the incidence of depression reached 26.85%, while there was no significant difference between the depression scores of the 2-year and 4-year follow-up periods and the baseline period. Akbaraly et al[39] proposed that the presence of MetS is associated with an increased risk of future depressive symptoms, and the results of this study further suggest that the longer the patients have MetS, the higher the risk of depression. Mulvahill et al[19] reported that the presence of MetS in elderly patients with depression is associated with the symptom severity of depression, and that poor antidepressant responses are observed in MetS patients. This indicates that the changes brought about by MetS not only increase the risk of depression but also affect the treatment efficacy. Therefore, patients must be identified and managed as early as possible to improve their outcomes.

Although the prevalence of depression in MetS patients was the highest after 7 years of follow-up, the predictive effect of the model established with the screened baseline information on the risk of depression in MetS patients after 7 years is limited. We found that the prediction model constructed by baseline CESD, PSMS, average sleep duration, number of chronic diseases, age, and weight had a good predictive effect on the risk of depression at the 2-year follow-up. It is worth noting that there are also complex interactions between these factors, such as depression and sleep duration, depression and chronic disease, chronic disease and ADL, and depression and ADL[40,41]. This suggests that paying attention to individuals who already have depressive symptoms, especially those with sleep problems and chronic diseases, is important for reducing the development of depression in MetS patients.

This study had some limitations. First, the patients in this study were from a community population, and the assessment of depressive symptoms was carried out with the self-rating scale used in a large epidemiological survey; therefore, the selected depression could not completely replace a diagnosis of depression. In addition, in the follow-up, to avoid too many influencing factors, we started from the data at 2 years, 4 years, and 7 years, instead of continuous analysis of the same group of patients. However, the prediction efficiency of the model constructed by this analysis method worsened with a longer follow-up time, indicating that the influencing factors within the follow-up years play a certain role. Finally, antidepressants may affect metabolism, but the use of antidepressants was not analyzed in this study; therefore, the results regarding the association between MetS and depression may have been affected.

In conclusion, this study described changes in the prevalence of depression in MetS patients over a 7-year period, screened out factors associated with the development of depression in MetS patients, and constructed a 2-year model to predict the risk of depression. The early identification of depression and the provision of interventions can improve patient outcomes.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is also common in individuals with psychiatric disorders and becoming more common in young people with depression. However, the relationship between depression and MetS remains unclear.

Many studies have explored the relationship between depression and MetS, especially in older people. China has entered an aging society. However, there are still few studies on the elderly in Chinese communities.

Based on a large community-based cohort study conducted in mainland China, we designed this study to address the following: (1) The prevalence of depression in MetS patients; (2) the changing trajectory of the prevalence of MetS during the 7-year follow-up; and (3) the risk factors for the development of depression in MetS patients and the construction of predictive models.

This study analyzed 7 years of follow-up data from the CHARLS database, screened the risk factors for depression in patients with metabolic syndrome, and constructed a predictive model for depression in patients with metabolic syndrome by regression analysis.

People with metabolic syndrome had a higher incidence of depression, which increased with the extension of follow-up time. The predictive model of baseline depression level, sleep duration, chronic disease, age, and weight was significant for depression risk after 2 years in patients with metabolic syndrome.

All in all, this study shows the prevalence of depression in middle-aged and elderly patients with MetS increases over time. More attention should be paid to early identification and intervention of depressive symptoms in MetS patients.

Mechanisms of depression in patients with MetS, early predictors and intervention modalities.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alkhatib AJ, Jordan S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Saklayen MG. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1964] [Cited by in RCA: 2416] [Article Influence: 345.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lan Y, Mai Z, Zhou S, Liu Y, Li S, Zhao Z, Duan X, Cai C, Deng T, Zhu W, Wu W, Zeng G. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in China: An up-dated cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Y, Mi J, Shan XY, Wang QJ, Ge KY. Is China facing an obesity epidemic and the consequences? The trends in obesity and chronic disease in China. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akbulut G, Köksal E, Bilici S, Acar Tek N, Yildiran H, Karadag MG, Sanlier N. Metabolic syndrome (MS) in elderly: a cross sectional survey. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;53:e263-e266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J; IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5130] [Cited by in RCA: 5325] [Article Influence: 266.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Asaye S, Bekele S, Tolessa D, Cheneke W. Metabolic syndrome and associated factors among psychiatric patients in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, South West Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:753-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr. Metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder: a review with a focus on bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:46-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lin YC, Lai CL, Chan HY. The association between rehabilitation programs and metabolic syndrome in chronic inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2018;260:227-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moreira FP, Jansen K, Cardoso TA, Mondin TC, Vieira IS, Magalhães PVDS, Kapczinski F, Souza LDM, da Silva RA, Oses JP, Wiener CD. Metabolic syndrome, depression and anhedonia among young adults. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Borshchev YY, Uspensky YP, Galagudza MM. Pathogenetic pathways of cognitive dysfunction and dementia in metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 2019;237:116932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Penninx BWJH, Lange SMM. Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric patients: overview, mechanisms, and implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20:63-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sjöberg L, Karlsson B, Atti AR, Skoog I, Fratiglioni L, Wang HX. Prevalence of depression: Comparisons of different depression definitions in population-based samples of older adults. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhou L, Ma X, Wang W. Relationship between Cognitive Performance and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Older Adults: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). J Affect Disord. 2021;281:454-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun X, Zhou M, Huang L, Nuse B. Depressive costs: medical expenditures on depression and depressive symptoms among rural elderly in China. Public Health. 2020;181:141-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pan A, Keum N, Okereke OI, Sun Q, Kivimaki M, Rubin RR, Hu FB. Bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1171-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 611] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Repousi N, Masana MF, Sanchez-Niubo A, Haro JM, Tyrovolas S. Depression and metabolic syndrome in the older population: A review of evidence. J Affect Disord. 2018;237:56-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sekita A, Arima H, Ninomiya T, Ohara T, Doi Y, Hirakawa Y, Fukuhara M, Hata J, Yonemoto K, Ga Y, Kitazono T, Kanba S, Kiyohara Y. Elevated depressive symptoms in metabolic syndrome in a general population of Japanese men: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liaw FY, Kao TW, Hsueh JT, Chan YH, Chang YW, Chen WL. Exploring the Link between the Components of Metabolic Syndrome and the Risk of Depression. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:586251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mulvahill JS, Nicol GE, Dixon D, Lenze EJ, Karp JF, Reynolds CF 3rd, Blumberger DM, Mulsant BH. Effect of Metabolic Syndrome on Late-Life Depression: Associations with Disease Severity and Treatment Resistance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2651-2658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang M, Chen J, Yin Z, Wang L, Peng L. The association between depression and metabolic syndrome and its components: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hiles SA, Révész D, Lamers F, Giltay E, Penninx BW. Bidirectional prospective associations of metabolic syndrome components with depression, anxiety, and antidepressant use. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:754-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Silić A, Karlović D, Serretti A. Increased inflammation and lower platelet 5-HT in depression with metabolic syndrome. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:72-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lemche AV, Chaban OS, Lemche E. Depression contributing to dyslipidemic cardiovascular risk in the metabolic syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chan KL, Cathomas F, Russo SJ. Central and Peripheral Inflammation Link Metabolic Syndrome and Major Depressive Disorder. Physiology (Bethesda). 2019;34:123-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Marazziti D, Rutigliano G, Baroni S, Landi P, Dell'Osso L. Metabolic syndrome and major depression. CNS Spectr. 2014;19:293-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dekker IP, Marijnissen RM, Giltay EJ, van der Mast RC, Oude Voshaar RC, Rhebergen D, Rius Ottenheim N. The role of metabolic syndrome in late-life depression over 6 years: The NESDO study. J Affect Disord. 2019;257:735-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ribeiro RP, Marziale MH, Martins JT, Ribeiro PH, Robazzi ML, Dalmas JC. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome among nursing personnel and its association with occupational stress, anxiety and depression. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2015;23:435-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Kachi Y, Yano E. Association of metabolic syndrome with atypical features of depression in Japanese people. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:532-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3155] [Cited by in RCA: 2614] [Article Influence: 237.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chen X, Crimmins E, Hu PP, Kim JK, Meng Q, Strauss J, Wang Y, Zeng J, Zhang Y, Zhao Y. Venous Blood-Based Biomarkers in the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study: Rationale, Design, and Results From the 2015 Wave. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188:1871-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhu L, Spence C, Yang JW, Ma GX. The IDF Definition Is Better Suited for Screening Metabolic Syndrome and Estimating Risks of Diabetes in Asian American Adults: Evidence from NHANES 2011-2016. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chen H, Mui AC. Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short form in older population in China. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:49-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77-84. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Moradi Y, Albatineh AN, Mahmoodi H, Gheshlagh RG. The relationship between depression and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;7:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chan S, Jia S, Chiu H, Chien WT, R Thompson D, Hu Y, Lam L. Subjective health-related quality of life of Chinese older persons with depression in Shanghai and Hong Kong: relationship to clinical factors, level of functioning and social support. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:355-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yuan MZ, Fang Q, Liu GW, Zhou M, Wu JM, Pu CY. Risk Factors for Post-Acute Coronary Syndrome Depression: A Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34:60-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tsuboi Y, Ueda Y, Sugimoto T, Naruse F, Ono R. Association between metabolic syndrome and disability due to low back pain among care workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2018;31:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2533] [Cited by in RCA: 2616] [Article Influence: 145.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Akbaraly TN, Kivimäki M, Brunner EJ, Chandola T, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A, Ferrie JE. Association between metabolic syndrome and depressive symptoms in middle-aged adults: results from the Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Maresova P, Javanmardi E, Barakovic S, Barakovic Husic J, Tomsone S, Krejcar O, Kuca K. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age - a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Jiang CH, Zhu F, Qin TT. Relationships between Chronic Diseases and Depression among Middle-aged and Elderly People in China: A Prospective Study from CHARLS. Curr Med Sci. 2020;40:858-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |