Published online Dec 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i12.1905

Revised: September 21, 2024

Accepted: October 15, 2024

Published online: December 19, 2024

Processing time: 91 Days and 2.8 Hours

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common complication of diabetes and the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness. It has a serious impact on the mental and physical health of patients.

To evaluate the anxiety and depression status of patients with DR, we examined their influencing factors.

Two hundred patients with DR admitted to the outpatient and inpatient departments of ophthalmology and endocrinology at our hospital were selected. A questionnaire was conducted to collect general patient information. Depression and anxiety were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale, respectively. The diabetes specific quality of life scale and Social Support Rating Scale were used to assess the quality of life of patients with DR and their social support, respectively. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the correlations.

The prevalence of depression and anxiety were 26% (52/200) and 14% (28/200), respectively. Regression analysis revealed that social support was associated with depression [odds ratio (OR) = 0.912, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.893-0.985] and anxiety (OR = 0.863, 95%CI: 0.672-0.994). Good quality of life (diabetes specific quality of life scale score < 40) was a protective factor against anxiety (OR = 0.738, 95%CI: 0.567-0.936) and depression (OR = 0.573, 95%CI: 0.4566-0.784). Visual impairment significantly increased the likelihood of depression (OR = 1.198, 95%CI: 1.143-1.324) and anxiety (OR = 1.746, 95%CI: 1.282-2.359). Additionally, prolonged diabetes duration and history of hypertension were significant risk factors for both conditions, along with a family history of diabetes.

Key factors influencing anxiety and depression in patients with DR include social support, quality of life, visual impairment, duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, and history of hypertension.

Core Tip: Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common complication of diabetes and the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness, which has a severe impact on the patient’s mental and physical health. We evaluated anxiety and depression status and their influencing factors in patients with DR. We conclude that social support, good quality of life, visual impairment, duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, and history of hypertension are critical factors for anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with DR. Health managers should screen for these risk factors to implement early prevention strategies to reduce depression and anxiety in patients with DR.

- Citation: Gao S, Liu X. Analysis of anxiety and depression status and their influencing factors in patients with diabetic retinopathy. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(12): 1905-1917

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i12/1905.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i12.1905

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common microvascular complication in patients with diabetes mellitus. DR can cause irreversible visual impairment or even blindness, which has a severe impact on mental and physical health[1]. According to the 2019 statistics of the International Diabetes Federation, there are 463 million patients with diabetes worldwide, including 116 million in China[2,3]. The prevalence of DR among patients with diabetes in China is 18.1%-35.0%[4]. Relevant literature indicates that patients with DR are prone to negative emotional reactions, such as anxiety, depression, fear, anger, and loss of confidence, which not only threaten their physical and mental health but also reduce their quality of life[5-7].

Studies have shown that depression and/or anxiety may be risk factors for diabetes. Patients with depression are more likely to develop diabetes than those without depression. Depression and anxiety are common mental disorders that affect different patient groups. The incidence of diabetes caused by depression is approximately 6.87%[8]. Compared with healthy people, depression and/or anxiety are more likely to occur in patients with chronic health conditions, such as diabetes. Depression and/or anxiety can negatively affect patients’ health-related quality of life, healthcare utilization, and healthcare costs can also be negatively affected by depression and/or anxiety[9]. Patients with DR and depression often have a negative attitude towards treatment, which often leads to poor blood sugar control, reduced treatment compliance, an increased incidence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and higher medical expenses[10]. Patients with depression are three times more likely to have reduced compliance than other patients, less likely to undergo surgery, and more likely to miss follow-up examinations. Although the impacts of myopia and glaucoma on the psychological state of patients have been reported[11], few studies have examined the psychological state of patients with DR. Therefore, screening for anxiety and depression in patients with DR is essential for effective patient management.

The Seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are rapid, reliable, and effective tools[12,13]. The GAD-7 was used to assess anxiety, and the PHQ-9 was used to assess depression. These scales together can better determine whether anxiety is accompanied by depression. Some ophthalmologists use the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, which are considered effective screening tools for assessing mental health status, primarily to assess anxiety and depression in patients with chronic eye disease. Therefore, in this study, we used GAD-7 and PHQ-9 to assess anxiety and depression, respectively. To evaluate the interaction between anxiety, depression, and DR treatment, we examined the anxiety and depression statuses of patients with DR and their influencing factors to provide a reference for corresponding psychological interventions for patients with DR in clinical practice.

Two hundred patients with DR admitted to our hospital’s outpatient and inpatient Departments of Ophthalmology and Endocrinology between March 2023 and April 2024 were selected for this cross-sectional study. Diagnostic criteria for DR in the “Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Diabetic Retinopathy in China” was met[14]. Data were collected within six months following the patients’ diagnosis of DR to enhance the understanding of the potential temporal associations between their DR status and their psychological state. Relevant information was obtained from electronic medical records and questionnaires of the hospital.

To ensure adequate statistical power, we calculated the sample size based on a preliminary survey of prevalence rates of anxiety and depression in diabetic patients in our region, aiming for a power of 0.80 and a significance level of 0.05. The survey process: (1) Before the survey, all assessors received formal training and were instructed to use standardized language to explain the contents of the scale. They were also required to strictly abide by their duties, avoid discrimination between respondents, and refrain from asking personal questions. The researchers were also evaluated for consistency; (2) Each questionnaire was collected and completed by two clinical researchers; (3) All content in the questionnaire was filled in and collected accurately and comprehensively; and (4) When guiding patients to fill in the form, a quiet environment was provided to avoid interference. If a patient had severe visual impairment, the scale was completed face-to-face with the help of an assessor. The assessor read and explained the items to patients and recorded their answers.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Participants must be between 18 and 80 years old; (2) Diagnosed with DR; (3) Able to speak and write Chinese well; and (4) Conscious and cognitively capable. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with acute complications of diabetes; (2) Patients with acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, severe infections, tumors, severe water and electrolyte disorders, and immune and blood system diseases; (3) Patients with dementia, various mental illnesses, or those who were unwilling to cooperate; (4) Patients with a history of drug or alcohol dependence, or those who had used antidepressants and anxiety drugs in the past; and (5) Pregnant or lactating women.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, and all patients voluntarily participated.

The collected data included age, sex, duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, history of hypertension, history of diabetes medication use, smoking, alcohol consumption, educational level, marital status, place of residence (rural or urban), and glycemic control. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were used as indicators of glycemic control and measured using high-performance liquid chromatography. In accordance with the Chinese guidelines for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack 2010[15], an HbA1c level of 53 mmol/mol (< 7.0%) was classified as indicative of good glycemic control, whereas a level of HbA1c ≥ 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) was deemed indicative of poor glycemic control[15]. As less than 5% of the data were missing, no handling of the missing data was necessary.

Visual acuity was measured using a standard logarithmic visual acuity chart. “VI” was defined as the presenting visual acuity of the better eye. We used this definition because it reflects the vision in real life. According to the International Classification of Diseases criteria, the VI level was classified as blindness, severe VI, moderate VI, mild VI, or no VI. The patients were classified as blind [logarithmic minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) ≥ 1.30], severe VI (1 ≤ logMAR < 1.30), moderate VI (0.48 ≤ logMAR < 1), mild VI (0.30 ≤ logMAR < 0.48), and no VI (logMAR < 0.30). We judged mild or no VI as no visual impairment or blindness and moderate or severe VI as visual impairment.

In this study, we assessed depression using the PHQ-9[13], which consists of nine items rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from zero (never) to three (every day). Scores on this scale can range from zero to 27, with a score of ≥ 10 indicating the presence of depression. The Chinese edition of the PHQ-9 has been demonstrated to exhibit strong reliability and validity, as indicated by a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.834 in our study.

The GAD-7 scale was used to evaluate anxiety levels[12]. This scale comprises seven symptom items aimed at gauging the severity and functional impact of anxiety symptoms experienced over the preceding two weeks. Responses were rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from zero (never) to three (every day), leading to a total score ranging from zero to 21. A score of ≥ 10 indicates the presence of anxiety. The Chinese version of GAD-7 is frequently used to evaluate the severity of anxiety symptoms in the Chinese population. In the current study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale stood at 0.938.

Social support was evaluated using the Social Support Rating Scale, specifically tailored to the Chinese context[16]. This scale comprised three subscales: Subjective support (perceived support level), objective support (visible support level), and support utilization (utilization of available support). Subjective support was gauged through four items, scored between eight and 32; objective support through three items, scored between one and 22; and support utilization through three items scored between three and 12. The total score ranges from 12 to 66, with higher scores indicating greater social support. The scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.89 and a test-retest reliability of 0.92 in previous studies. Scores of 12 to 22 signify low support, 23 to 44 moderate support, and 45 to 66 high support[17].

Individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus in China were evaluated using a diabetes specific quality of life scale (DSQL)[18]. This validated questionnaire comprises 24 items that assess physiological, social, psychological, and therapy-related aspects that affect the quality of life. The scores on the four domains range from 24 to 120 points, with higher scores indicating a lower quality of life. When identifying the good and poor quality of life-based on DSQL scores below 40, the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were 94.5% and 91.0%[18]. In this study, a DSQL score of < 40 was considered to indicate a good quality of life.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. Descriptive statistics were used to present continuous variables with means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. Pearson’s χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Based on binary logistic regression analysis, we evaluated the factors influencing negative emotions in patients with DR using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Negative emotions were defined as the outcome variable, and the participants were categorized into two groups: Those experiencing negative emotions and those without. Two-sided tests were used in the regression model with a significance level of P < 0.05.

The demographic and clinical information of patients with DR are shown in Table 1. Among the 200 patients, 52 (26.0%) had depression, 28 (14.0%) had anxiety, the mean age (standard deviation) was 54.62 (10.85) years, 104 (52.0%) were women, and 42 (21.0%) had a college degree or above. Fifty-eight patients had diabetes for less than 5 years, and 142 had diabetes for ≥ 5 years. Among these patients, 84.5% had visual impairment. Thirty-nine (19.5%) patients had good quality of life, 48 (24.0%) had high social support, 74 (37.0%) had a history of drinking, 68 (34.0%) had a history of smoking, and 172 (86.00%) had a family history of diabetes. A total of 136 patients (68.0%) had hypertension.

| Variable | Patients (n = 200) | Percentage (%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 96 | 48.0 |

| Female | 104 | 52.0 |

| Age (year) | 54.62 ± 10.85 | / |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 23 | 11.5 |

| Secondary | 37 | 18.5 |

| Senior high school | 98 | 49.0 |

| College or above | 42 | 21.0 |

| Duration of diabetes, year | ||

| < 5 | 58 | 29.0 |

| ≥ 5 | 142 | 71.0 |

| Depression | ||

| Yes | 52 | 26.0 |

| No | 148 | 74.0 |

| Anxiety | ||

| Yes | 28 | 14.0 |

| No | 172 | 86.0 |

| Visual impairment | ||

| Yes | 169 | 84.5 |

| No | 31 | 15.5 |

| Good quality of life (DSQL score < 40) | ||

| Good | 39 | 19.5 |

| Poor | 161 | 80.5 |

| Social support | ||

| Low support | 69 | 34.5 |

| Moderate support | 83 | 41.5 |

| High support | 48 | 24.0 |

| History of smoking | ||

| Yes | 68 | 34.0 |

| No | 132 | 66.0 |

| History of drinking | ||

| Yes | 74 | 37.0 |

| No | 126 | 63.0 |

| Complicated with hypertension | ||

| Yes | 136 | 68.0 |

| No | 64 | 32.0 |

| Diabetes history | ||

| Yes | 172 | 86.0 |

| No | 28 | 14.0 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 89 | 44.5 |

| Urban | 111 | 55.5 |

| Diabetes type | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | 5 | 2.5 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 195 | 97.5 |

| Diabetes medication | ||

| Oral hypoglycemic drugs | 63 | 31.5 |

| Insulin injection | 41 | 20.5 |

| Both | 96 | 48.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 115 | 57.5 |

| Single | 32 | 16.0 |

| Divorced/widowed | 53 | 26.5 |

| Blood glucose control | ||

| Good | 37 | 18.5 |

| General | 96 | 48.0 |

| Bad | 67 | 33.5 |

Table 2 shows the results of univariate analysis for each factor and depression. The results showed significant differences between patients with and without depression in terms of education level, duration of diabetes, visual impairment, quality of life, social support, and hypertension (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in age, marital status, place of residence, smoking, drinking, or type of diabetes between the groups (P > 0.05).

| Variable | Without depression (n = 148) | Depression (n = 52) | χ2 | P value |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 76 | 20 | 3.257 | 0.083 |

| Female | 72 | 32 | ||

| Education | 12.841 | 0.006 | ||

| Primary | 18 | 5 | ||

| Secondary | 28 | 9 | ||

| Senior high school | 63 | 35 | ||

| College or above | 39 | 3 | ||

| Duration of diabetes, year | 4.423 | 0.035 | ||

| < 5 | 37 | 21 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 111 | 31 | ||

| Visual impairment | 9.556 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 132 | 37 | ||

| No | 16 | 15 | ||

| Good quality of life (DSQL score < 40) | 27.379 | < 0.001 | ||

| Good | 16 | 23 | ||

| Poor | 132 | 29 | ||

| Social support | 13.274 | 0.001 | ||

| Low support | 57 | 12 | ||

| Moderate support | 65 | 18 | ||

| High support | 26 | 22 | ||

| History of smoking | 1.568 | 0.211 | ||

| Yes | 54 | 14 | ||

| No | 94 | 38 | ||

| History of drinking | 0.105 | 0.745 | ||

| Yes | 43 | 31 | ||

| No | 105 | 21 | ||

| Complicated with hypertension | 12.421 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 109 | 27 | ||

| No | 39 | 25 | ||

| Diabetes history | 3.293 | 0.696 | ||

| Yes | 149 | 23 | ||

| No | 7 | 21 | ||

| Residence | 0.046 | 0.829 | ||

| Rural | 72 | 17 | ||

| Urban | 76 | 35 | ||

| Diabetes type | 1.367 | 0.618 | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | 3 | 2 | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | 145 | 50 | ||

| Diabetes medication | 2.632 | 0.355 | ||

| Oral hypoglycemic drugs | 35 | 28 | ||

| Insulin injection | 26 | 15 | ||

| Both | 87 | 9 | ||

| Marital status | 0.938 | 0.626 | ||

| Married | 88 | 27 | ||

| Single | 23 | 9 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 37 | 16 | ||

| Blood glucose control | 1.438 | 0.487 | ||

| Good | 24 | 5 | ||

| General | 69 | 25 | ||

| Bad | 55 | 22 |

Table 3 presents the results of univariate analysis for each factor and anxiety level. The results showed that there were significant differences between anxious patients and non-anxious patients in terms of smoking history, duration of diabetes, visual impairment, good quality of life, social support, family history of diabetes, combined hypertension, and blood sugar control levels (P < 0.05). No notable variations were found in age, education level, marital status, location of residence, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, or type of diabetes (P > 0.05).

| Variable | Without anxiety (n = 172) | Anxiety (n = 28) | χ2 | P value |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 78 | 18 | 3.459 | 0.063 |

| Female | 94 | 10 | ||

| Education | 5.885 | 0.117 | ||

| Primary | 21 | 2 | ||

| Secondary | 32 | 5 | ||

| Senior high school | 79 | 19 | ||

| College or above | 40 | 2 | ||

| Duration of diabetes, year | 33.459 | < 0.001 | ||

| < 5 | 37 | 21 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 135 | 7 | ||

| Visual impairment | 39.489 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 157 | 12 | ||

| No | 15 | 16 | ||

| Good quality of life (DSQL score < 40) | 29.389 | < 0.001 | ||

| Good | 23 | 16 | ||

| Poor | 149 | 12 | ||

| Social support | 21.445 | < 0.001 | ||

| Low support | 67 | 2 | ||

| Moderate support | 73 | 10 | ||

| High support | 32 | 16 | ||

| History of smoking | 5.558 | 0.018 | ||

| Yes | 53 | 15 | ||

| No | 119 | 13 | ||

| History of drinking | 0.388 | 0.534 | ||

| Yes | 67 | 7 | ||

| No | 151 | 21 | ||

| Complicated with hypertension | 12.337 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 125 | 11 | ||

| No | 47 | 17 | ||

| Diabetes history | 46.252 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 160 | 12 | ||

| No | 12 | 16 | ||

| Residence | 0.832 | 0.362 | ||

| Rural | 125 | 18 | ||

| Urban | 47 | 10 | ||

| Diabetes type | 0.288 | 0.592 | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | 4 | 1 | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | 168 | 27 | ||

| Diabetes medication | 5.354 | 0.069 | ||

| Oral hypoglycemic drugs | 49 | 14 | ||

| Insulin injection | 36 | 5 | ||

| Both | 87 | 9 | ||

| Marital status | 0.445 | 0.801 | ||

| Married | 98 | 17 | ||

| Single | 27 | 5 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 47 | 6 | ||

| Blood glucose control | 7.928 | 0.019 | ||

| Good | 29 | 8 | ||

| General | 79 | 17 | ||

| Bad | 64 | 3 |

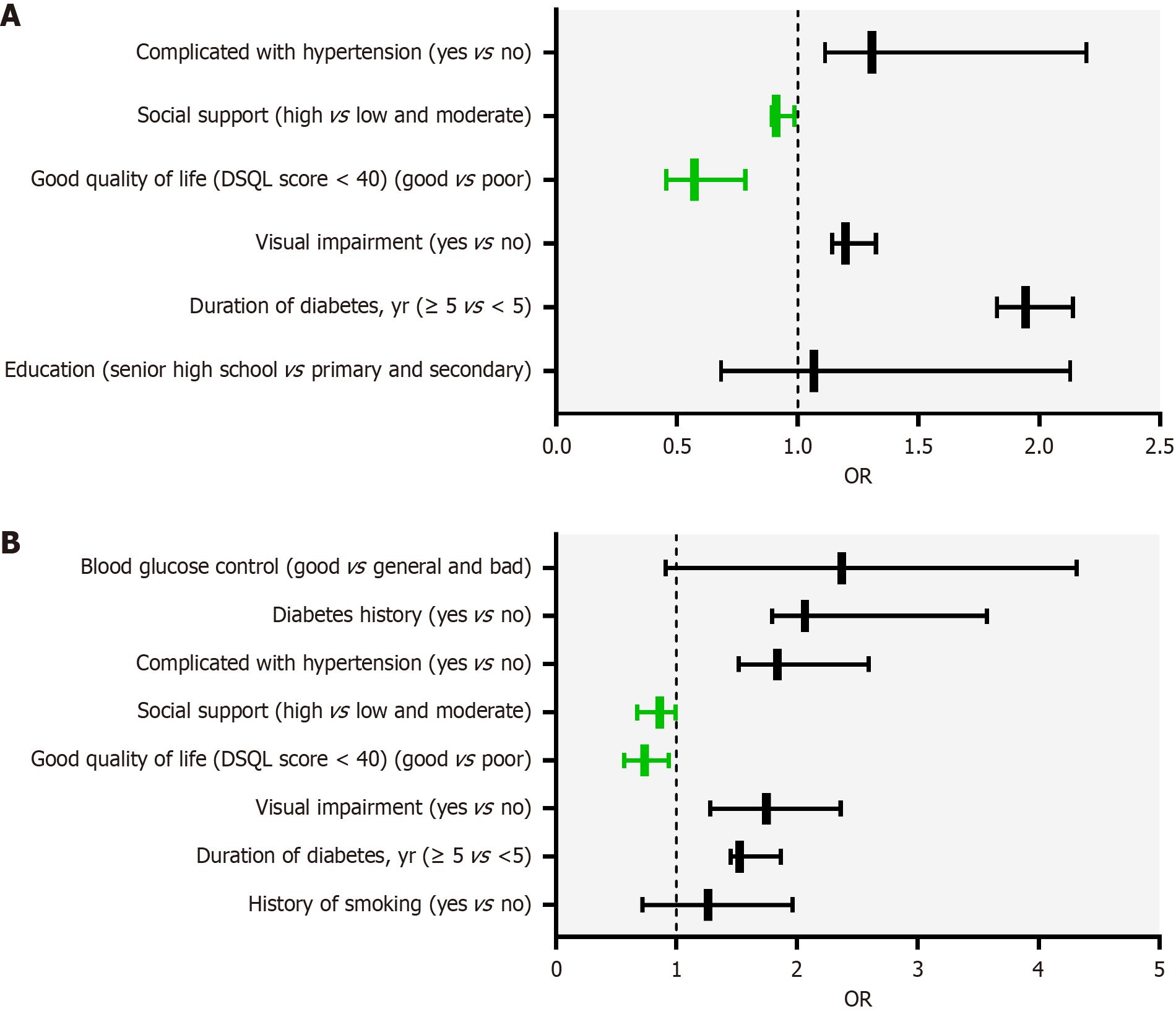

Considering depression as the dependent variable (0 = no, 1 = yes), and according to the results of the univariate analysis in Table 2, the variables with statistically significant differences (education level, duration of diabetes, visual impairment, good quality of life, social support, and hypertension) were used as independent variables. Binary logistic regression was used to analyze the independent factors influencing depression in patients with DR. The results showed that the longer the duration of diabetes, the higher the risk of depression (OR = 1.943, 95%CI: 1.826-2.139). Visual impairment (OR = 1.198, 95%CI: 1.143-1.324) and high blood pressure (OR = 1.307, 95%CI: 1.113-2.194) are risk factors for depression. Good quality of life and social support are protective factors against depression (OR = 0.573, 95%CI: 0.456-0.784). As shown in Table 4, patients with high social support were less likely to experience depression than those with low social support (OR = 0.912, 95%CI: 0.893-0.985).

| Variable | Reference | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Education | ||||

| Senior high school | Primary and secondary | 0.926 | 1.067 | 0.683-2.128 |

| Duration of diabetes, year | ||||

| ≥ 5 | < 5 | 0.041 | 1.943 | 1.826-2.139 |

| Visual impairment | ||||

| Yes | No | 0.048 | 1.198 | 1.143-1.324 |

| Good quality of life (DSQL score < 40) | ||||

| Good | Poor | 0.046 | 0.573 | 0.456-0.784 |

| Social support | ||||

| High support | Low and moderate support | 0.021 | 0.912 | 0.893-0.985 |

| Complicated with hypertension | ||||

| Yes | No | 0.035 | 1.307 | 1.113-2.194 |

Considering anxiety as the dependent variable (0 = no, 1 = yes), and according to the results of the univariate analysis in Table 3, variables with statistically significant differences (smoking history, duration of diabetes, visual impairment, quality of life, social support, hypertension, family history of diabetes, and blood sugar control level) were used as independent variables. Binary logistic regression was used to analyze the independent factors influencing anxiety in patients with DR. The results showed that the longer the duration of diabetes, the higher the risk of anxiety (OR = 1.526, 95%CI: 1.451-1.863), and visual impairment was a risk factor for anxiety (OR = 1.746, 95%CI: 1.282-2.359). High blood pressure was also a risk factor for anxiety (OR = 1.836, 95%CI: 1.517-2.592), while a good quality of life was a protective factor for anxiety (OR = 0.738, 95%CI: 0.567-0.936). Social support is also a protective factor against anxiety. A family history of diabetes (OR = 2.065, 95%CI: 1.792-3.571) was an independent risk factor for anxiety. Patients with high social support were less likely to experience anxiety (OR = 0.863, 95%CI: 0.672-0.994). Figure 1 illustrates the visualization results for the independent influencing factors listed in Table 5.

| Variable | Reference | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| History of smoking | ||||

| Yes | No | 0.876 | 1.264 | 0.721-1.965 |

| Duration of diabetes, year | ||||

| ≥ 5 | < 5 | 0.032 | 1.526 | 1.451-1.863 |

| Visual impairment | ||||

| Yes | No | 0.028 | 1.746 | 1.282-2.359 |

| Good quality of life (DSQL score < 40) | ||||

| Good | Poor | 0.013 | 0.738 | 0.567-0.936 |

| Social support | ||||

| High support | Low and moderate support | 0.029 | 0.863 | 0.672-0.994 |

| Complicated with hypertension | ||||

| Yes | No | < 0.001 | 1.836 | 1.517-2.592 |

| Diabetes history | ||||

| Yes | No | 0.017 | 2.065 | 1.792-3.571 |

| Blood glucose control | ||||

| Good | General and bad | 1.525 | 2.369 | 0.915-4.317 |

In the present study, we found that the overall mental health of patients with DR was poor. Among all patients, 52 (26.0%) had symptoms of depression, and 28 (14.0%) had symptoms of anxiety. The prevalence of depression was higher in the current population than in the general population[19]. The prevalence of depression in the present study was higher than that reported in another study[20]. However, another study reported a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with diabetes[21]. Prevalence disparities may arise from variations in measurement instruments and study populations. Although there were no notable disparities in the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms among individuals with diabetes, significant variations were observed when compared to those in the general population. Accordingly, the mental well-being of patients with DR warrants continued monitoring.

Social support also plays a vital role in psychological adaptation[22]. Previous studies have shown that social support is indirectly associated with mental health in patients with diabetes[23]. In a study by Chiu et al[24], health behaviors accounted for 13% of the association between depressive symptoms and glycemic control. The results showed a negative correlation between social support and depression (OR = 0.912, 95%CI: 0.893-0.985) and anxiety (OR = 0.863, 95%CI: 0.672-0.994), which is consistent with the results of previous studies[25]. However, a higher quality of life reduced the odds of depression (OR = 0.573, 95%CI: 0.456-0.784) and anxiety (OR = 0.738, 95%CI: 0.567-0.936) in patients with DR, which is consistent with the results of other studies on patients[26].

In addition, vision loss and DR treatment methods are issues of great concern for patients with DR in ophthalmology outpatient clinics and inpatient settings and deserve further discussion. Patients with vision-threatening DR may experience greater social and emotional stress than those without it. Previous studies have found that visual changes are important factors associated with changes in mental health[27]. There was a positive correlation among vision loss, depression, and anxiety symptoms[28]. The results of this study showed that patients with visual impairments had a higher risk of depression (OR = 1.198, 95%CI: 1.143-1.324) and anxiety (OR = 1.746, 95%CI: 1.282-2.359), which is consistent with previous research results.

In addition, the results of this study indicated that patients with hypertension were more likely to experience depre

Our research indicates that patients with a familial predisposition to diabetes display heightened levels of anxiety compared with those without such a history. Furthermore, another study revealed that individuals at risk for type 2 diabetes reported more subjective stress than their non-diabetic counterparts[21]. Although previous studies have linked the incidence of DR to a family history of diabetes, the potential causal relationship between familial diabetes history and anxiety symptoms in patients with DR remains unclear[33]. Our findings suggest that a family history of diabetes independently increases the risk of anxiety (OR = 2.065, 95%CI: 1.792-3.571), which is in line with the existing research.

Our findings can help clinicians provide more personalized support and counseling and clinically incorporate mental health support into treatment plans for patients with chronic eye diseases such as DR. For example, the PHQ-9 was integrated into the routine visits of DR Patients. Healthcare providers should use the tool at the initial diagnosis and each follow-up appointment. GAD-7 was administered during the same visit. Patients diagnosed with DR Were evaluated at least every 6 months, or more frequently, for those with scores above the established cutoff (PHQ-9 and GAD-7 ≥ 10 points). In cases of mild to moderate depression and anxiety, a brief cognitive behavioural therapy intervention was offered as part of the care plan. Consider referring a trained mental health clinician to the ophthalmology or endo

In addition, future studies should implement randomized controlled trials that focus on specific interventions designed to reduce anxiety and depression in patients with DR. Potential interventions could include cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, or group therapy sessions targeting diabetes management and emotional support. Multiple interventions, including medical and psychological care, should be explored simultaneously. Integrating diabetes education, regular mental health assessments, and a collaborative care model that includes endocrinologists, ophthalmologists, and mental health professionals can provide holistic treatment strategies. Tailoring interventions according to the individual needs of patients, such as the severity of visual impairment, duration of diabetes, and previous mental health history, will improve the effectiveness of treatment strategies. Future studies should also evaluate the comorbidities that may affect anxiety and depression in patients with DR, such as obesity, hypertension, and other diabetes-related complications. Understanding how these factors interact can inform comprehensive treatment strategies to improve overall patient care and outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, the reliance on self-administered questionnaires for patient assessment may have introduced a data recall bias and potentially inadequately captured the full spectrum of mental health conditions. Second, the use of a cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of causal relationships between the variables. Future research should address these limitations. Third, the association between family history of DR and anxiety symptoms, which served as a confounding factor in this study, warrants further investigation. Finally, this study was conducted at a single-center hospital in China, which limits the generalizability of the findings to Chinese patients with DR. We included standardized clinical assessments of visual acuity and objective measures of glycemic control (HbA1c levels) as part of our data collection. This dual approach enhances the validity of our findings and allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between DR, visual impairment, anxiety, and depression. Future studies should consider integrating additional objective assessments and focus on longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials to evaluate the effectiveness of specific interventions aimed at reducing anxiety and depression in patients with DR while also exploring the adverse effects of treatments and the role of comorbid conditions, such as standardized clinical evaluations of DR severity using retinal imaging techniques and detailed ocular examinations, to support the reliability of the findings further.

This study shows that some patients with DR exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety. Social support and a good quality of life were negatively correlated with depression and anxiety. Diabetes duration, visual impairment, and hypertension are the risk factors for depression and anxiety in patients with DR. A family history of diabetes is a risk factor for anxiety. Therefore, treating patients with DR should focus on controlling blood sugar levels and improving vision. Encouraging patients to take care of themselves as much as possible, strengthening psychological counseling, and providing psychotherapy and behavioral intervention for patients with anxiety and depression can help them achieve maximum recovery from the disease, obtain the best psychological comfort, and improve their quality of life.

| 1. | Tan TE, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy: Looking forward to 2030. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1077669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Artasensi A, Pedretti A, Vistoli G, Fumagalli L. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Multi-Target Drugs. Molecules. 2020;25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA, Ogurtsova K, Shaw JE, Bright D, Williams R; IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5345] [Cited by in RCA: 5924] [Article Influence: 987.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 4. | Zhang B, Wang Q, Zhang X, Jiang L, Li L, Liu B. Association between self-care agency and depression and anxiety in patients with diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xu X, Zhao X, Qian D, Dong Q, Gu Z. Investigating Factors Associated with Depression of Type 2 Diabetic Retinopathy Patients in China. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khoo K, Man REK, Rees G, Gupta P, Lamoureux EL, Fenwick EK. The relationship between diabetic retinopathy and psychosocial functioning: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:2017-2039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rees G, Xie J, Fenwick EK, Sturrock BA, Finger R, Rogers SL, Lim L, Lamoureux EL. Association Between Diabetes-Related Eye Complications and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:1007-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Campayo A, de Jonge P, Roy JF, Saz P, de la Cámara C, Quintanilla MA, Marcos G, Santabárbara J, Lobo A; ZARADEMP Project. Depressive disorder and incident diabetes mellitus: the effect of characteristics of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:580-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang Y, Cui Y, Li Y, Lu H, Huang H, Sui J, Guo Z, Miao D. Network analysis of depressive and anxiety symptoms in older Chinese adults with diabetes mellitus. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1328857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kalva P, Shi A, Kakkilaya A, Saleh I, Albadour M, Kooner K. Associations between depression and diabetic retinopathy in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011 to 2018. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2024;37:262-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li B, Zhou C, Gu C, Cheng X, Wang Y, Li C, Ma M, Fan Y, Xu X, Chen H, Zheng Z. Modifiable lifestyle, mental health status and diabetic retinopathy in U.S. adults aged 18-64 years with diabetes: a population-based cross-sectional study from NHANES 1999-2018. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gong Y, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Zhu X, Wang X, Shen B, Xian J, Ding Y. Validation of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) as a screening tool for anxiety among pregnant Chinese women. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cui C, Li Y, Wang L. The Association of Illness Uncertainty and Hope With Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Cross-sectional Study of Psychological Distress in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Women. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hou X, Wang L, Zhu D, Guo L, Weng J, Zhang M, Zhou Z, Zou D, Ji Q, Guo X, Wu Q, Chen S, Yu R, Chen H, Huang Z, Zhang X, Wu J, Wu J, Jia W; China National Diabetic Chronic Complications (DiaChronic) Study Group. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy in adults with diabetes in China. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang YJ, Zhang SM, Zhang L, Wang CX, Dong Q, Gao S, Huang RX, Huang YN, Lv CZ, Liu M, Qin HQ, Rao ML, Xiao Y, Xu YM, Yang ZH, Wang YJ, Wang CX, Wang JZ, Wang WZ, Wang J, Wang WJ, Wu J, Wu SP, Zeng JS, Zhang SM, Zhang L, Zhao XQ, Zhong LY. Chinese guidelines for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack 2010. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:93-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li JN, Jiang XM, Zheng QX, Lin F, Chen XQ, Pan YQ, Zhu Y, Liu RL, Huang L. Mediating effect of resilience between social support and compassion fatigue among intern nursing and midwifery students during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang B, Zhang W, Sun X, Ge J, Liu D. Physical Comorbidity and Health Literacy Mediate the Relationship Between Social Support and Depression Among Patients With Hypertension. Front Public Health. 2020;8:304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dong D, Lou P, Wang J, Zhang P, Sun J, Chang G, Xu C. Interaction of sleep quality and anxiety on quality of life in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Baxter AJ, Charlson FJ, Cheng HG, Shidhaye R, Ferrari AJ, Whiteford HA. Prevalence of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: a systematic analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:832-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang L, Li J, Dang Y, Ma H, Niu Y. Relationship Between Social Capital and Depressive Symptoms Among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Northwest China: A Mediating Role of Sleep Quality. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:725197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sun N, Lou P, Shang Y, Zhang P, Wang J, Chang G, Shi C. Prevalence and determinants of depressive and anxiety symptoms in adults with type 2 diabetes in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Al-Dwaikat TN, Rababah JA, Al-Hammouri MM, Chlebowy DO. Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Psychological Wellbeing of Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. West J Nurs Res. 2021;43:288-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Harding KA, Pushpanathan ME, Whitworth SR, Nanthakumar S, Bucks RS, Skinner TC. Depression prevalence in Type 2 diabetes is not related to diabetes-depression symptom overlap but is related to symptom dimensions within patient self-report measures: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2019;36:1600-1611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chiu CJ, Wray LA, Beverly EA, Dominic OG. The role of health behaviors in mediating the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a structural equation modeling approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:67-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hernández-Moreno L, Senra H, Moreno N, Macedo AF. Is perceived social support more important than visual acuity for clinical depression and anxiety in patients with age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy? Clin Rehabil. 2021;35:1341-1347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pan CW, Wang S, Wang P, Xu CL, Song E. Diabetic retinopathy and health-related quality of life among Chinese with known type 2 diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:2087-2093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Frank CR, Xiang X, Stagg BC, Ehrlich JR. Longitudinal Associations of Self-reported Vision Impairment With Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Among Older Adults in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:793-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ekemiri KK, Botchway EN, Ezinne NE, Sirju N, Persad T, Masemola HC, Chidarikire S, Ekemiri CC, Osuagwu UL. Comparative Analysis of Health- and Vision-Related Quality of Life Measures among Trinidadians with Low Vision and Normal Vision-A Cross-Sectional Matched Sample Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Geldsetzer P, Vaikath M, Wagner R, Rohr JK, Montana L, Gómez-Olivé FX, Rosenberg MS, Manne-Goehler J, Mateen FJ, Payne CF, Kahn K, Tollman SM, Salomon JA, Gaziano TA, Bärnighausen T, Berkman LF. Depressive Symptoms and Their Relation to Age and Chronic Diseases Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Rural South Africa. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74:957-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ahmed SMJ, Awadelgeed BA, Miskeen E. Assessing the Psychological Impact of the Pandemic COVID -19 in Uninfected High-Risk Population. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:391-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, Collins BS, Hilliard ME, Isaacs D, Johnson EL, Kahan S, Khunti K, Leon J, Lyons SK, Perry ML, Prahalad P, Pratley RE, Seley JJ, Stanton RC, Gabbay RA; on behalf of the American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S19-S40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 1310] [Article Influence: 655.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (70)] |

| 32. | Johnson HM. Anxiety and Hypertension: Is There a Link? A Literature Review of the Comorbidity Relationship Between Anxiety and Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Maghbooli Z, Pasalar P, Keshtkar A, Farzadfar F, Larijani B. Predictive factors of diabetic complications: a possible link between family history of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |