INTRODUCTION

In the past 20 years, accumulating research investigating the bidirectional link between diabetes mellitus (DM) and depression has gradually revealed the relationship between the two diseases[1]. DM is a metabolic disease characterized by chronically elevated blood glucose levels, leading to damage to a variety of tissues and organs. According to the latest research, DM is mainly classified into two types, 1 and 2[2], the mechanisms of which mainly involve biological dysfunction of insulin and resistance to insulin action. Genetically, mutations in GCK associated with MODY2 account for most monogenic DM cases among children and adolescents[3]. Studies have shown that globally, the number of cases of DM is rapidly increasing, and the prevalence of prediabetes is also on the rise[4], suggesting that more individuals are at risk. The prevalence of type 2 DM is of particular concern due to changing lifestyles, increases in life expectancies, and aging populations. Improper management of DM can lead to a variety of serious complications including nephropathy[5], cardiovascular disease[6], neuropathy[7], and retinopathy[8]. These complications significantly reduce the quality of life of those affected and impose a significant economic burden on public health systems[9]. Treatment of DM relies heavily on medication, dietary control, and exercise. Factors such as poor diet, stress, and inadequate medical resources, are important challenges in the management of DM. However, the specific problems and conditions faced in addressing these challenges differ between developed and developing countries. Although developed countries and some Caribbean countries have developed more detailed guidelines for the management of DM, the content and quality of these guidelines vary across countries, especially in resource-poor settings where implementation of the guidelines is often limited[10]. In contrast, some developing countries in Asia have implemented health behavior interventions to prevent and manage DM, the economic feasibility and effectiveness of these interventions need to be further validated in resource-constrained settings[11].

Depression is a prevalent mood disorder clinically defined by enduring feelings of low mood, reduced interest in activities, altered self-perception, and significant changes in physical functioning[12]. The definition and management of treatment-resistant depression have become important topics in current depression research and clinical practice[13]. According to statistics, depression represents a significant global disease burden, with its prevalence steadily rising over the years, affecting diverse demographics such as the elderly and adolescents[14,15]. In a review, Monroe and Harkness[16] described the impact of life course on depression and its recurrence, emphasizing the importance of an individual’s experience in the progression of the disease, including pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and combination(s) thereof, such as immune targets[17], antidepressant drugs[18] and electroconvulsive therapy[19]. Breakthroughs have been difficult to achieve due to the complexity of DM etiology, individual differences among patients, and the uncertainty of treatment response. Moreover, the management of depression in both developed and developing countries is influenced by multiple socioeconomic factors. However, the lack of medical resources and social pressures in developing countries make the diagnosis and treatment of depression more complex and difficult. In the global south, mental health policies and discourses are often developed in ways that ignore the specific needs and contexts of these countries, resulting in limited effectiveness of management and treatment approaches. In addition, depression is often associated with malnutrition and persistent social and economic pressures in developing countries, further compounding the complexity of depression and its management[20].

The intricate bidirectional relationship between DM and depression profoundly affects patient health management and quality of life. Previous studies have shown that individuals with DM have a higher risk for developing depression and vice versa[21,22]. This two-way relationship is influenced by physiological mechanisms, pathological factors, and sociodemographic variables including social psychology, sex, and ethnicity. Recognizing and emphasizing this relationship is crucial for shaping effective public health policies and clinical management. Integrating this understanding can pave the way for more comprehensive health management program that enhance both prevention and treatment outcomes[23].

PHYSIOLOGICAL AND PATHOLOGICAL MECHANISMS OF THE BIDIRECTIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DM AND DEPRESSION

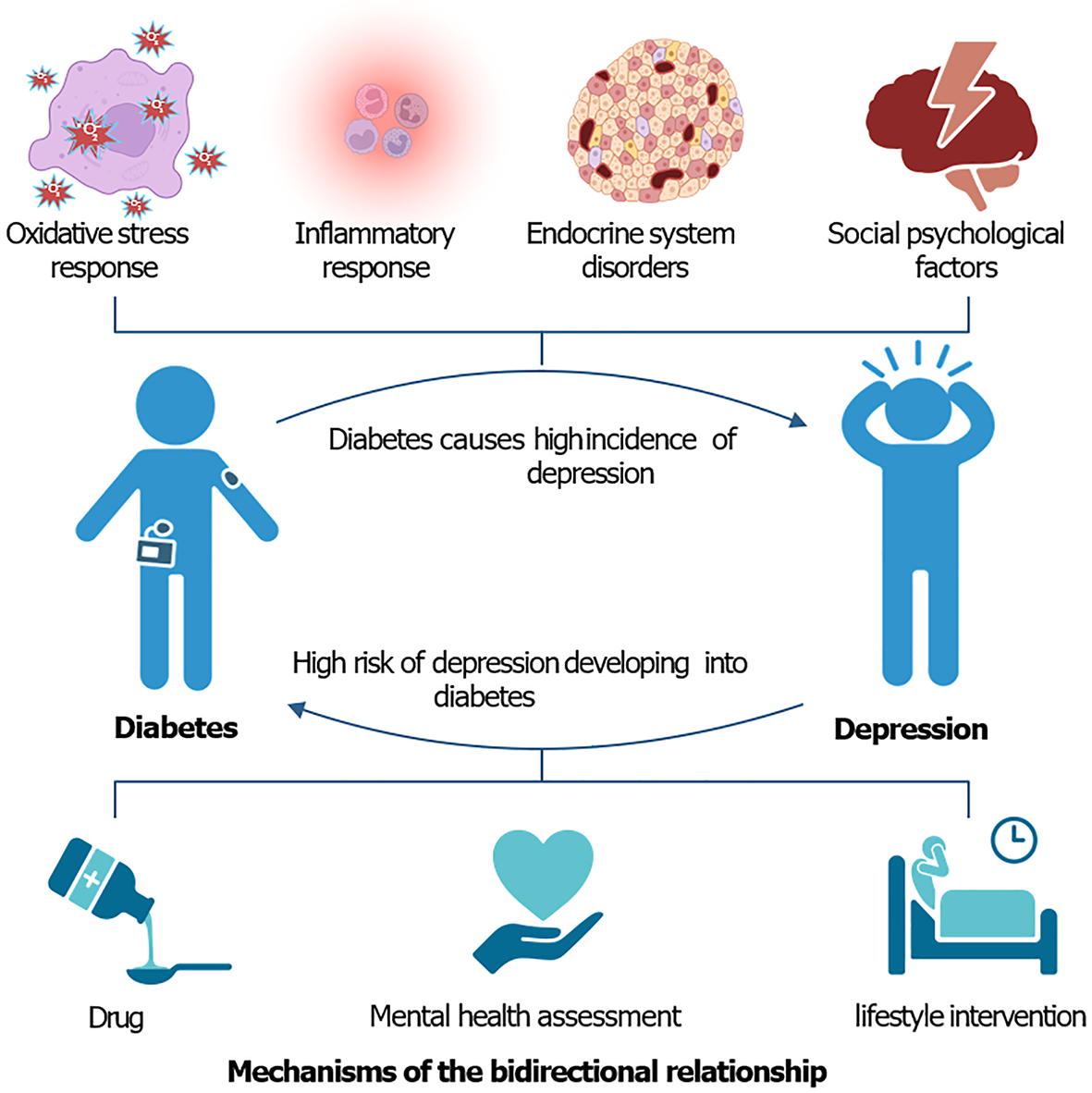

DM typically affects brain function through physiological mechanisms such as inflammation and oxidative stress, which in turn increases the risk for depression. Inflammation plays an important role in both DM and depression (Figure 1). Among patients with DM, inflammatory mediators[24] such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, which promotes the entry of inflammatory mediators into the brain, which in turn directly or indirectly interfere with neurotransmitter systems, such as serotonin and dopamine, affect mood and cognitive function with chronic low-grade inflammation, mainly due to abnormal activation of the immune system caused by hyperglycemia[25], which triggers depression[26]. DANCR plays a role in the relationship between DM and depression by regulating the expression of miR-214-5p and KLF5 and affecting cellular inflammatory responses and apoptosis[27]. It has also been found that blood levels of miR-128 are significantly elevated in patients with type 2 DM and depression. miR-128 plays a role in the nervous system by regulating brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF), which affect neuroplasticity and cognitive function[28]. DM is often associated with increased oxidative stress; more specifically, a decrease in the body’s antioxidant capacity or an increase in free radical production. Oxidative stress not only directly damages neurons, but also exacerbates neuroinflammation by inducing an inflammatory response, thereby exacerbating depressive symptoms[29]. In addition, animal experiments by Ni et al[30] using models demonstrated that intermittent hypoxia can downregulate TREM2, which leads to enhanced activation of the IFNAR1-STAT1 signaling pathway, increasing the number of pro-inflammatory microglial cells, leading to synaptic damage and triggering anxiety[30]. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated the involvement of microvascular mechanisms in DM-induced depression[31]. There is also an overlap between depression and DM in terms of abnormalities in the neuroendocrine system, and activation of the stress response system may lead to an increase in glucocorticoid levels[32], which may be associated with the development of depression. Alterations in BDNF are associated with neurodevelopment and plasticity, and changes in BDNF in patients with depression and DM may affect disease progression and treatment outcomes[33].

Figure 1 The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and depression—pathogenesis and treatment strategies.

Psychosocial mechanisms also play a role in the association between DM and depression (Figure 1). For example, income inequality affects an individual’s access to healthcare resources, which in turn affects the management of DM and treatment of depression. Moreover, populations with lower education levels often lack the health literacy and skills to manage chronic conditions, which may make them more vulnerable to the combined effects of DM and depression[34]. Social capital and sleep quality are strongly associated with depressive symptoms in patients with DM, indicating the importance of social support and quality of life in mental health[35]. Moreover, stereotypes and medication burden may influence the severity of depressive symptoms through mediating effects in patients[36]. In particular, some anti-hyperglycemic agents have the potential to positively affect depressive symptoms, suggesting potential co-treatment strategies[37].

Depression affects the management and prognosis of DM, mainly through lifestyle changes and endocrine dysregulation. Patients with depression often exhibit poor lifestyle habits, such as an irregular diet, lack of exercise, and excessive use of tobacco and alcohol, which directly affect the management of DM. For example, an unbalanced diet and sedentary lifestyle can contribute to weight gain and worsen glycemic control, thereby exacerbating DM[38]. This is accompanied by abnormalities in the neuroendocrine system, such as an increased stress response and increased secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormones, which may also lead to poor glycemic control. Chronic stress affects insulin sensitivity and exacerbates the development and management of DM[39]. Moreover, psychological barriers or lack of willpower may lead to reduced treatment adherence, such as a reluctance to take medication or follow medical advice and, in turn, affect the prognosis of DM[40]. It is important to note that individuals with DM do not spontaneously develop depression, nor do those with depression inevitably develop DM. Comorbidity between the two diseases usually occurs in response to a combination of specific physiopathological mechanisms, psychological stress responses, and socioenvironmental factors.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL INSIGHTS: DEPRESSION IN PATIENTS WITH DM

The high prevalence of depression among patients with DM has been verified in a large number of epidemiological studies in recent years. There are differences in the bidirectional relationship between different types of DM and depression, with type 2 DM having the most significant bidirectional relationship with depression. It has been reported that approximately 10%–20% of patients with type 2 DM experience depression, a proportion that is more than twice the rate in the general population[41]. Similarly, in a study across 12 countries, Lloyd et al[42] found a significantly increased prevalence of major depressive disorders in patients with type 2 DM. An inverse association with the risk for developing DM was also evident, with depressed patients having a higher risk for developing DM. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Graham et al[43] revealed that patients with depression had an approximately 40% increased susceptibility to type 2 DM. The prevalence of depression varies among patients with DM of different ages. It has also been found that younger individuals with diabetes (e.g., 18-25 year old “emerging adults”) are significantly more likely to experience depression and suicidal ideation than older age groups, which may be related to the stresses of life and psychological adjustment problems they encounter[44]. Sex is also a significant influencing factor. Depression is more prevalent among females with DM than among males, and its detrimental effects on glycemic control are particularly pronounced in females[45]. Significant variations have been observed in the co-occurrence of DM and depression across diverse ethnic groups. The association between DM and depression is stronger among specific minority groups (e.g., African Americans and Latinos), which may be related to socioeconomic status, cultural background, and level of medical care[46]. There were, however, several potential biases and limitations in these epidemiological studies, particularly those with cross-sectional designs. First, cross-sectional studies primarily provide information about the associations between diseases without determining causality. Second, their reliance on self-reporting could affect the accuracy and validity of the results. Third, some potential confounders, such as lifestyle and socioeconomic status, are difficult to control and may influence the occurrence of diabetes, depression, and their association. Further studies, therefore, are required to address these limitations.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

To identify and manage patients with coexisting DM and depression in clinical settings, establishing a bidirectional relationship between the two diseases is essential (Figure 1). Identifying depression in patients with DM in clinical practice requires systematic mental health assessment. Mukherjee and Chaturvedi[41] suggested that patients with DM should be assessed regularly using a standardized depression screening scale (e.g., the Patient Health Questionnaire) for the early detection of depressive symptoms. In addition, patients with DM often exhibit atypical depressive symptoms, such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and changes in appetite, which must be differentiated from the symptoms of DM itself. Amanat et al[47] highlighted the critical role of physical activity in managing type 2 DM, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and supporting weight management to optimize glycemic control. The complexity of long-term medication, insufficient patient adherence to treatment plans, and the risk for comorbidities are all difficulties encountered in the management of DM treatment. Significant changes in cardiorespiratory function in patients with DM have been noted in one study[48], which poses additional challenges for treatment and health management. The diabetes care team should include mental health professionals, such as psychologists and psychotherapists, to integrate the patient’s psychological and physical well-being into daily management. Habib et al[46] noted that multidisciplinary collaboration is the key to the effective identification and management of DM-related depression. For patients with coexisting DM and depression, an integrated management strategy is essential for controlling blood glucose levels and providing psychological support. Integrated management strategies include appropriate medications, behavioral therapies, and lifestyle interventions[49]. In recent years, advances in digital health technology have provided new opportunities for the joint management of DM and depression, enabling personalized and convenient treatment through preventive care and telemedicine. For example, mobile health applications, remote monitoring devices, and artificial intelligence-based decision support systems have demonstrated promising potential in the management of DM and depression[50]. Treatment of depression positively affects DM control. Effective treatment of depression reduces the risk for developing DM and enhances glycemic management in patients with existing DM[43].

RESEARCH DIRECTIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Recently, academic and medical attention has increased the current understanding of the complexity of the bidirectional association between DM and depression. Research suggests that not only do these two disorders have a high comorbidity rate among patients, but that they may also have a mutually reinforcing relationship. More specifically, the presence of one disorder may increase a patient’s risk for developing the other disorder and vice versa[51,52].

To gain a deeper understanding of this complex causal relationship, researchers urgently need to strengthen the power of longitudinal studies, particularly randomization studies. By tracking all baseline parameters and monitoring their progress or regression over time, it is possible to reveal the time series of disease progression and its correlates and, thus, identify potential intervention strategies. This approach will not only help determine how specific factors influence the onset and progression of DM and depression but also provide a more definitive theoretical basis for personalized medicine and precision treatment.

Multi-omics studies have demonstrated promising potential for exploring disease mechanisms[53]. For example, advances in genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have enabled researchers to investigate the molecular-level mechanisms of disease development. These approaches not only help to explain why specific individuals are more susceptible to these two diseases, but also open the possibility of developing therapeutic programs that are tailored to individual genomic profiles. However, there are multiple potential ethical considerations and practical challenges facing researchers in future longitudinal and multi-omics studies investigating DM and depression. For example, in joint studies investigating DM and depression, sensitive patient health data may reveal health risks and psychological states that involve data privacy security issues. In addition, because multi-omics studies often rely on high-quality samples and advanced analytical techniques, it may be difficult for resource-constrained groups to participate, resulting in the limited generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the results of multi-omics studies are usually highly complex and specific, and the application of these results to clinical practice is challenging.

To effectively address these public health challenges, interdisciplinary collaboration is critical[46]. Integrating expertise from clinical medicine, psychology, and the basic sciences not only improves the overall understanding of the complexity of disease, but also facilitates the development and practical application of novel treatments. By working together, we can hope to provide more effective strategies and solutions for the prevention and treatment of diabetes and depression as a comorbid disease, thereby improving the quality of life of patients and reducing the associated health risks.

CONCLUSION

The interplay between diabetes and depression has been extensively investigated and validated in recent studies, revealing a bidirectional relationship. Individuals diagnosed with diabetes frequently experience comorbid depression, and conversely, those with depression are at higher risk of developing diabetes. This reciprocal relationship extends beyond mental health to encompass physiological mechanisms. In terms of physiological mechanisms, inflammation and oxidative stress significantly contribute to the pathogenesis of both diseases. Inflammatory mediators directly or indirectly trigger the onset and aggravation of depression by impacting the blood-brain barrier and neurotransmitter systems. Epidemiologic studies have shown that the prevalence of depression is significantly higher among diabetic patients, as well as a significantly increased risk of developing diabetes in depressed patients. A combination of mechanistic and epidemiologic studies is essential to better prevent and treat both diseases. In-depth exploration of the biological mechanisms of the diseases can lay the foundation for personalized treatment and precision medicine, such as revealing the molecular-level changes of the diseases through genomics, proteomics and metabolomics. Meanwhile, the advancement of longitudinal studies will help to understand the time series of disease development and related factors, providing support for early intervention. In summary, interdisciplinary collaboration and integrated management strategies are key to addressing the bidirectional association between diabetes and depression. By integrating expertise from clinical medicine, psychology, and basic science, we can better understand and address this complex public health challenge and provide more effective treatment and prevention strategies for patients.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade A, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Bucangende EN; Zhai X S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG