Published online Sep 19, 2023. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i9.675

Peer-review started: May 24, 2023

First decision: June 12, 2023

Revised: June 25, 2023

Accepted: August 2, 2023

Article in press: August 2, 2023

Published online: September 19, 2023

Processing time: 114 Days and 9.1 Hours

Spiritual wellbeing emphasizes optimistic and positive attitudes while self-regulating negative emotions when coping with stress. However, there have only been a few small studies of spiritual wellbeing of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients undergoing chemotherapy. The core factors influencing spiritual wellbeing in this clinical population are still unclear.

To identify factors influencing spiritual wellbeing among patients with PDAC receiving chemotherapy.

A total of 143 PDAC patients receiving chemotherapy were enrolled from January to December 2022. Patients completed general information questionnaires including: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being 12 Item Scale (FACIT-Sp-12), European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) and Zung’s Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS). Independent sample t-test, one-way analysis of variance, Pearson’s correlation analysis, and multiple linear regression analysis were adopted for statistical analyses. P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Total spiritual wellbeing (FACIT-Sp-12) score was 32.16 ± 10.06 points, while dimension sub-scores were 10.85 ± 3.76 for faith, 10.55 ± 3.42 for meaning, and 10.76 ± 4.00 for peace. Total spiritual wellbeing score was negatively correlated with SAS score for anxiety and with the symptom domain of EORTC QLC-C30. Conversely, spiritual wellbeing score was positively correlated with global health status and EORTC QLQ-C30 role functioning domain score. Multivariate regression analysis identified educational level, health insurance category, symptom domain, functional role domain, and global health status as significant independent factors influencing spiritual wellbeing among PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy (R2 = 0.502, P < 0.05).

Individualized spiritual support is needed for PDAC patients. Health, daily functioning, emotional, cognitive, and social function status should be taken into account to promote implementation of spirituality in nursing practice.

Core Tip: Identifying the core factors influencing spiritual wellbeing of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients undergoing chemotherapy and formulating individualized spiritual care regimens can improve quality of life. However, there have only been a few small studies on spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy. The core factors influencing spiritual wellbeing in this clinical population are still unclear. In this study, we analyzed factors influencing the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy, the newest study of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy in Mainland China.

- Citation: Wei LL, Zhang ST, Liao Y, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Mi N. Factors influencing spiritual wellbeing among pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients receiving chemotherapy. World J Psychiatry 2023; 13(9): 675-684

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v13/i9/675.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i9.675

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a tumor of the digestive tract with a high degree of malignancy, poor prognosis, and high mortality rate[1]. In recent years, the application of surgery combined with neoadjuvant chem-otherapy has prolonged the survival of PDAC patients. However, PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy experience surgical and chemotherapy-induced adverse events, negative emotions, changes in family and social relationships, and high treatment expenses; all of which can negatively influence health outcomes[2]. As an important part of human health, spiritual wellbeing emphasizes the role of maintaining optimistic and positive attitudes while self-regulating negative emotions when coping with stressful events. Studies have shown that spiritual wellbeing is positively correlated with health and contributes to better prognosis and quality of life[3,4]. Therefore, identifying the core factors influencing spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy and formulating individualized spiritual care regimens can improve quality of life among this patient group. However, there have only been a few small studies of the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy. The core factors influencing spiritual wellbeing in this clinical population are still unclear[5,6]. Therefore, this study was designed to identify factors influencing the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy to provide a theoretical basis for formulating individualized spiritual care regimens.

According to the sample size estimation method in Nursing Research Methods[7], sample size should be 5–10 times the number of independent variables. Twenty-two independent variables were included in this study, and a nonresponse rate of 10% was considered as the upper limit. According to the formula, n = 22 × (5-10) × (1+10%), the sample size should range from 121 to 242.

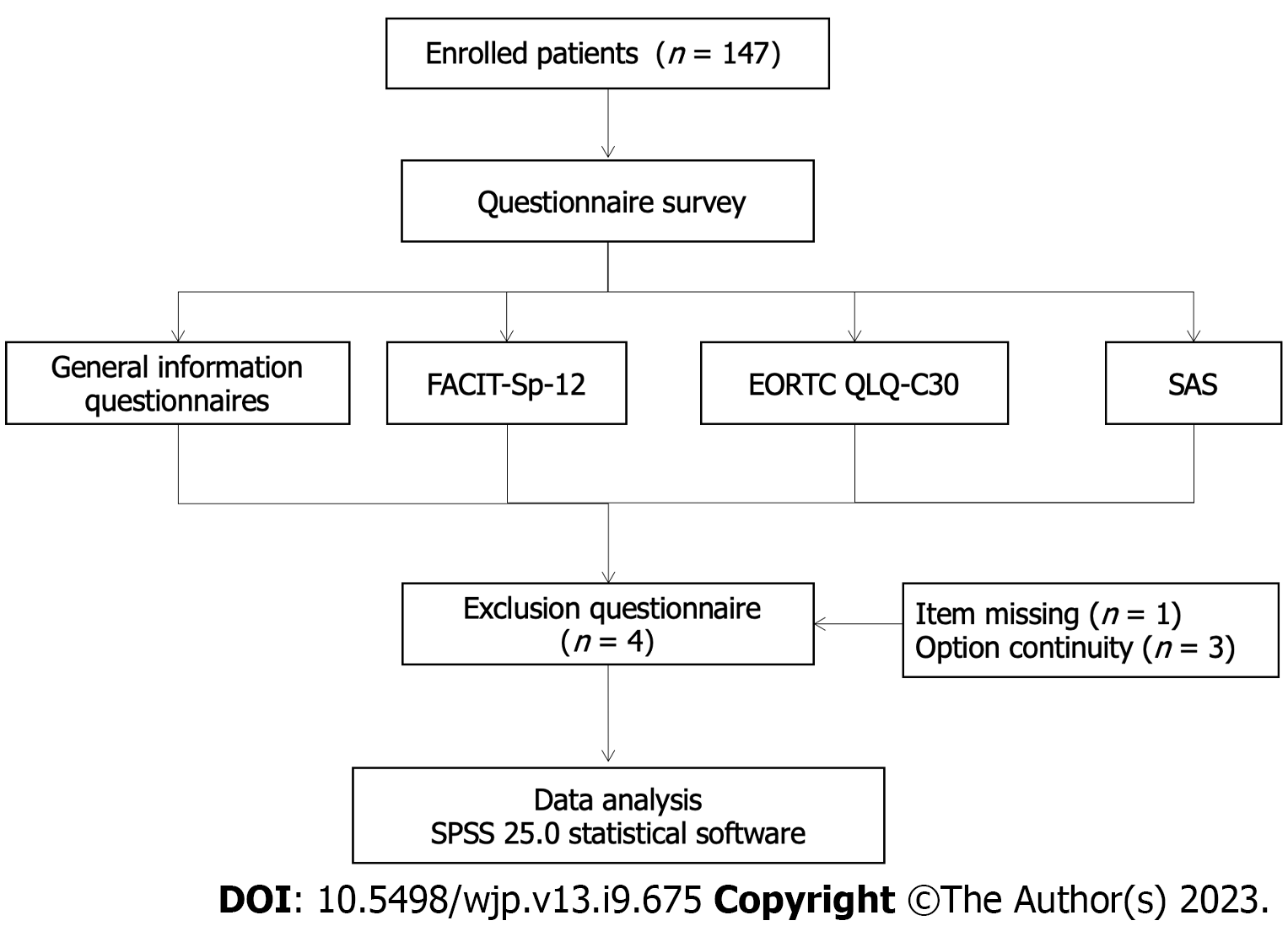

PDAC patients receiving cyclic adjuvant chemotherapy in our department from January 2022 to December 2022 were recruited, and 147 questionnaires were distributed and collected with a recovery rate of 100%. After four invalid questionnaires were excluded, 143 were finally included in this study with an effective recovery rate of 97.28% (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were: (1) Diagnosis of PDAC; (2) classified as locally progressive stage disease; (3) age 18–75 years; (4) requiring cyclic chemotherapy; and (5) clearly expressed willingness to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Mental illness or cognitive dysfunction; and (2) insufficient energy or physical strength to complete the questionnaire.

General information questionnaire: A self-designed questionnaire was distributed with items on gender, age, educational level, occupation, family income, marital status, religious beliefs, number of children, medical expenses, date of disease diagnosis, and recurrence of the disease.

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being 12 Item Scale (FACIT-Sp-12): Spiritual well-being was measured by the FACIT-Sp-12 originally formulated by Brady et al[8] and translated into Mandarin by Liu et al[9]. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale and assessed on three dimensions: faith, meaning, and peace, with higher scores indicating greater spiritual wellbeing. The Cronbach’s α coefficient ranged from 0.711 to 0.920 with high validity, indicating that the FACIT-Sp-12 can be widely applied among cancer patients for the assessment of spiritual wellbeing.

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30): The EORTC QLQ-C30 was a standard questionnaire designed for cancer patients by EORTC. It consisted of 30 items assessing eight quality of life dimensions. Items 29 and 30 were divided into seven levels, and scores ranged from 1 to 7 points, while all other items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale. For the functional and global health status domains, higher scores were indicative of better quality of life. For the symptom domain, a higher score indicated worse quality of life. The reliability of EORTC QLQ-C30 was 0.988 and validity was 0.989[10].

Zung’s Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS): The SAS was designed by William W.K. Zung to reflect the degree of anxiety among patients. All items were graded on a 4-point Likert scale. A score < 50 was considered indicative of little or no anxiety, 50–60 of mild anxiety, 61–70 of moderate anxiety, and > 70 of severe anxiety[11].

Prior to the survey, all investigators received standardized training to guarantee the objectivity and accuracy of data collection. All scales were completed by scanning QR codes. During the survey, investigators explained the response method and precautions for each scale by unified instructions. Each section of the questionnaire was completed by the patients independently or with the assistance of investigators. Investigators addressed any questions from patients to ensure the efficiency of questionnaire completion. After the survey, investigators examined whether any item was missing and instructed the patients to supply the missing response. Each scale required < 10 min to complete.

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 software. Quantitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage, and qualitative data as mean ± SD if it was under normal distribution. Total questionnaire scores and domain scores were compared among subgroups using the independent samples t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) as indicated. Associations among total scores and domain were first assessed using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Potential factors influencing spiritual wellbeing were then included in a multiple logistic regression model. A P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant for all tests.

The total score of FACIT-Sp-12 of PDAC patients treated with chemotherapy was (32.16 ± 10.06), (10.85 ± 3.76) for the dimension of faith, (10.55 ± 3.42) for meaning and (10.76 ± 4.00) for peace, respectively. The SAS score was calculated as (45.59 ± 6.44). The EORTC QLQ-C30 score was (83.74 ± 2.85), (74.01 ± 21.41) for global health status and (8.88 ± 1.79) for the symptom domain. The results of all questionnaires are summarized in Table 1.

| Item | Score range | Scale score | mean item score |

| FACIT-Sp-12 | 0-48 | 32.16 ± 10.06 | 2.68 ± 0.84 |

| Faith | 0-16 | 10.85 ± 3.76 | 2.71 ± 0.94 |

| Meaning | 0-16 | 10.55 ± 3.42 | 2.64 ± 0.86 |

| Peace | 0-16 | 10.76 ± 4.00 | 2.69 ± 1.00 |

| SAS | 0-100 | 45.59 ± 6.44 | 2.28 ± 0.32 |

| Anxiety | 0-20 | 5.48 ± 1.96 | 1.37 ± 0.49 |

| Vegetative disorder | 0-40 | 11.01 ± 2.90 | 1.38 ± 0.36 |

| Exercise-induced anxiety | 0-30 | 15.43 ± 2.40 | 2.57 ± 0.40 |

| Concurrent symptoms of anxiety and vegetative disorder | 0-10 | 4.54 ± 1.27 | 2.27 ± 0.64 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | 0-100 | 83.74 ± 2.85 | 5.58 ± 0.19 |

| Body | 0-100 | 18.46 ± 15.52 | 3.69 ± 3.10 |

| Role functioning | 0-100 | 16.32 ± 19.33 | 8.16 ± 9.67 |

| Emotion | 0-100 | 14.74 ± 18.65 | 3.69 ± 4.67 |

| Cognition | 0-100 | 19.35 ± 19.74 | 9.67 ± 9.87 |

| Social function | 0-100 | 28.79 ± 24.80 | 14.39 ± 12.40 |

| QLQ-C30 global health status | 0-100 | 74.01 ± 21.41 | 37.00 ± 10.70 |

| QLQ-C30 symptom domain | 0-11 | 8.88 ± 1.79 | 0.68 ± 0.14 |

| Fatigue | 0-100 | 75.76 ± 21.04 | 25.25 ± 7.01 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0-100 | 89.04 ± 17.48 | 44.52 ± 8.74 |

| Pain | 0-100 | 82.63 ± 21.29 | 41.32 ± 10.65 |

| Shortness of breath | 0-100 | 85.32 ± 21.89 | |

| Insomnia | 0-100 | 76.46 ± 27.07 | |

| Loss of appetite | 0-100 | 76.22 ± 27.59 | |

| Constipation | 0-100 | 86.71 ± 20.98 | |

| Diarrhea | 0-100 | 86.71 ± 20.98 | |

| Economic difficulty | 0-100 | 85.55 ± 25.50 | |

Significant differences were observed in the spiritual wellbeing regarding sex, education level, household monthly income, type of health insurance and recurrence of PDAC patients treated with chemotherapy. Spiritual wellbeing scores were higher in males than females, in higher-educated compared to less-educated patients, and in patients at first diagnosis (without recurrence) (all P < 0.05), but showed no significant difference among age group, duration of illness, or occupational group (Table 2). Further, scores also differed by household monthly income and type of health insurance (both P < 0.05). The spiritual wellbeing score of patients with a household monthly income of 3000–5000 Yuan was the highest up to (35.00 ± 8.64), and the lowest score was (29.37 ± 10.65) in their counterparts with income of 1000–3000 Yuan. Patients with workers’ medical insurance had the highest spiritual wellbeing score of 35.68 ± 7.80, and those with other types of health insurance obtained the lowest score of 19.42 ± 11.87.

| Item | No. of cases, n (%) | Spiritual wellbeing score | T/F | P value | |

| Sex | Male | 93 (65.0) | 32.89 ± 10.54 | 1.187 | 0.024 |

| Female | 50 (35.0) | 30.80 ± 9.06 | |||

| Age (yr) | 18–44 | 18 (12.6) | 29.67 ± 10.32 | 0.4951 | 0.687 |

| 45–59 | 79 (55.2) | 32.39 ± 10.16 | |||

| 60–74 | 36 (25.2) | 32.39 ± 10.52 | |||

| 75–89 | 10 (7.0) | 32.16 ± 10.06 | |||

| Education level | Primary school or below | 37 (25.9) | 26.03 ± 10.48 | 12.3991 | < 0.001 |

| Middle and high school | 62 (43.4) | 32.19 ± 9.33 | |||

| Technical and further education | 20 (14.0) | 33.6 ± 7.00 | |||

| Undergraduate degree or above | 24 (16.8) | 40.33 ± 7.10 | |||

| Occupation | Farmer | 73 (51.0) | 32.49 ± 10.55 | 1.0471 | 0.374 |

| Retired | 34 (23.8) | 32.21 ± 10.23 | |||

| Full-time employment | 20 (14.0) | 28.90 ± 9.99 | |||

| Other | 16 (11.2) | 34.63 ± 6.86 | |||

| Household monthly income | > 1000 Yuan | 35 (24.5) | 31.03 ± 11.09 | 2.6851 | 0.049 |

| 1000–3000 Yuan | 30 (21.0) | 29.37 ± 10.65 | |||

| 3000-5000 Yuan | 56 (39.2) | 35 ± 8.64 | |||

| 5000 Yuan plus | 22 (15.4) | 30.55 ± 9.80 | |||

| Spouse | Yes | 124 (86.7) | 31.59 ± 10.05 | -1.749 | 0.082 |

| No | 19 (13.3) | 35.89 ± 9.57 | |||

| Religious belief | Yes | 3 (2.1) | 35 ± 14.73 | 0.493 | 0.623 |

| No | 140 (97.9) | 32.1 ± 10.01 | |||

| Number of offspring | 0 | 4 (2.8) | 39 ± 4.24 | 1.6541 | 0.180 |

| 1 | 65 (45.5) | 33.42 ± 9.37 | |||

| 2 | 58 (40.6) | 31.10 ± 10.37 | |||

| 3 or more | 16 (11.2) | 29.19 ± 11.77 | |||

| Type of health insurance | Employee Health Insurance | 62 (43.4) | 35.68 ± 7.80 | 11.2821 | < 0.001 |

| New rural pension scheme | 63 (44.1) | 30.98 ± 9.65 | |||

| Urban medical insurance | 6 (4.2) | 33.67 ± 10.35 | |||

| Other | 12 (8.4) | 19.42 ± 11.87 | |||

| Time after diagnosis | ≤ 6 mo | 69 (48.3) | 33.42 ± 8.44 | 1.2781 | 0.284 |

| 7–12 mo | 40 (28.0) | 30.95 ± 11.11 | |||

| 13–24 months | 17 (11.9) | 28.76 ± 13.26 | |||

| ≥ 24 mo | 17 (11.9) | 33.29 ± 9.76 | |||

| Recurrence | Yes | 28 (19.6) | 26.18 ± 12.19 | -3.035 | < 0.001 |

| No | 115 (80.4) | 32.16 ± 10.06 | |||

The correlation coefficients between spiritual wellbeing and anxiety, and symptom domain of EORTC QLQ-C30 were calculated as -0.357 and -0.322, and those between spiritual wellbeing and global health status, and function domain were 0.464 and 0.421 (P < 0.05). These findings suggested that spiritual wellbeing was negatively correlated with anxiety level as measured by the SAS score and with the quality of life symptom domain according to EORTC QLQ-C30. The high spiritual wellbeing was predictive of lower anxiety and better symptom-related quality of life. Conversely, heightened anxiety and severity of symptoms were associated with lower spiritual wellbeing. In addition, spiritual wellbeing was positively correlated with global health status and the functional role domain of quality of life (all P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Item | Spiritual wellbeing | Faith | Meaning | Peace |

| SAS | -0.357b | -0.329b | -0.345b | -0.293b |

| Anxiety | -0.371b | -0.366b | -0.319b | -0.316b |

| Vegetative disorder | -0.466b | -0.420b | -0.469b | -0.378b |

| Exercise-induced anxiety | 0.053 | 0.067 | 0.047 | 0.030 |

| Concurrent symptoms of anxiety and vegetative disorder | 0.092 | 0.061 | 0.079 | 0.106 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | 0.421b | 0.381b | 0.437b | 0.329b |

| Body | 0.292b | 0.302b | 0.266b | 0.225b |

| Role functioning | 0.181a | 0.177a | 0.223b | 0.100 |

| Emotion | 0.436b | 0.387b | 0.436b | 0.362b |

| Cognition | 0.324b | 0.275b | 0.335b | 0.271b |

| Social function | 0.301b | 0.229b | 0.368b | 0.229b |

| QLQ-C30 global health status | 0.464b | 0.362b | 0.435b | 0.456b |

| QLQ-C30 symptom domain | -0.322b | -0.320b | -0.331b | -0.226b |

| Fatigue | -0.264b | -0.294b | -0.245b | -0.177a |

| Nausea and vomiting | -0.169a | -0.210a | -0.144 | -0.105 |

| Pain | -0.275b | -0.278b | -0.294b | -0.180a |

| Shortness of breath | -0.214a | -0.231b | -0.183a | -0.166a |

| Insomnia | -0.281b | -0.229b | -0.302b | -0.234b |

| Loss of appetite | -0.309b | -0.295b | -0.323b | -0.225b |

| Constipation | -0.189a | -0.213a | -0.183a | -0.119 |

| Diarrhea | -0.199a | -0.162 | -0.242b | -0.143 |

| Economic difficulty | -0.098 | -0.042 | -0.156 | -0.074 |

In multivariate regression analysis, FACIT-Sp-12 total score was considered the dependent variable and all variables significantly associated with the wellbeing score in ANOVA (anxiety, functional role domain of EORTC QLQ-C30, global health status, and symptom domain) were included as independent variables (default values are shown in Table 4). Educational level, type of health insurance, functional role domain of the EORTC QLQ-C30, symptom domain of the EORTC QLQ-30, and global health status of the EORTC QLQ-30 were identified as independent factors influencing spiritual wellbeing (overall R2 = 0.502, P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| Independent variable | Default value |

| Sex | Male = 1; female = 2 |

| Education level | Primary school or below = 1; middle and high school = 2; technical and further education = 3; bachelor degree and above = 4 |

| Household monthly income (Yuan) | < 1000 = 1; 1000-3000 = 2; 3000-5000 = 3; > 5000 = 4 |

| Type of health insurance | Workers’ medical insurance = 1; new rural pension scheme = 2; urban medical insurance = 3; other = 4 |

| Recurrence | Yes = 1; No = 2 |

| Item | FACIT-Sp-12 | ||||

| b | sb | b’ | t value | P value | |

| (Constant) | -74.696 | 42.693 | - | -1.750 | 0.082 |

| Sex | 0.518 | 1.397 | 0.025 | 0.371 | 0.711 |

| Education level | 3.297 | 0.639 | 0.332 | 5.156 | < 0.001 |

| Household monthly income | 0.013 | 0.65 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.984 |

| Type of health insurance | -3.02 | 0.798 | -0.263 | -3.786 | < 0.001 |

| recurrence | 2.198 | 1.739 | 0.087 | 1.264 | 0.209 |

| SAS anxiety | -0.214 | 0.12 | -0.137 | -1.786 | 0.076 |

| C30 global health status | 0.988 | 0.416 | 0.279 | 2.371 | 0.019 |

| C30 symptom domain | 0.152 | 0.037 | 0.323 | 4.117 | < 0.001 |

| C30 functional domain | 1.647 | 0.643 | 0.293 | 2.559 | 0.012 |

Spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients treated with chemotherapy needs to be enhanced. The total spiritual wellbeing score for patients with PDAC undergoing chemotherapy was in the mid-range (32.16 ± 10.06), consistent with other patient populations described by Xue et al[12] and Liu et al[13], and indicating the need for improvement through spiritual care regimens. The diagnosis of PDAC places heavy emotional and financial burdens on patients[14]. Although surgery combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy can prolong survival[15], the overall survival rate is still low[16], which increases uncertainty about life and reduces patient confidence in treatment outcome. Cyclic chemotherapy is a substantial imposition, disrupting lifestyle and social participation, with side effects including physical pain and other discomforts that further increase the psychological burden[13], which may eventually lower spiritual wellbeing. Therefore, medical staff should actively provide spiritual support, identify patients’ negative emotions, strengthen health education, emphasize the importance of companionship, and create a positive atmosphere. Potential strategies included sharing treatment success stories, encouraging patients to reflect on the meaning of life, and alleviating negative emotion to help the patient achieve harmony of body, heart, and spirit.

Individual differences in spiritual wellbeing were related to demographics and clinical status. Although PDAC incidence was lower in females than males, the former reported significantly lower spiritual wellbeing, possibly due to a greater propensity for negative emotions in response to stressful events[17,18]. However, at present, the causes of gender difference on spiritual wellbeing are still unclear and warrant further investigation to formulate gender-specific spiritual care regimens for PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy. Patients with higher educational level reported greater spiritual wellbeing. Many of these patients also reported a heavy economic burden (76%), which may explain why spiritual wellbeing was higher among PDAC patients in households with a monthly income of 3000–5000 Yuan compared to those with income of 1000–3000 Yuan. However, several studies[19-21] have found that household income was not an influencing factor on the spiritual wellbeing of cancer patients. Patients with higher household monthly incomes and urban medical insurance experience less pressure from medical expenses and were able to afford better chemotherapy; therefore, this group of patients could maintain a better quality of life. Nonetheless, the subgroup of patients with monthly income > 5000 Yuan did not have significant additional benefits, possibly due to the small sample size. Recurrence of PDAC was also an influencing factor for spiritual wellbeing as recurrence can intensify uncertainty and reduce individual capacity to resolve difficulties, thereby lowering spiritual wellbeing. Medical staff should act to address issues such as economic pressure, negative emotions, and poor knowledge of treatment benefits and challenges, especially among female patients, to improve spiritual wellbeing.

In this study, the mean SAS score was in the very low range, albeit higher than reported previously[5] and was negatively correlated with spiritual wellbeing. Symptoms such as dyspnea (83.91%), irritation (78.32%), fatigue (51.05%), poor sleep (48.25%), and gastrointestinal reactions (46.15%) can induce anxiety. Long-term anxiety among these patients may evoke hypersensitivity to negative events, causing loss of faith in the treatment process, reducing optimism, and even leading to suicide[22,23]. Therefore, medical staff should closely monitor and attempt to mitigate anxiety by regulating respiratory and gastrointestinal functions, improving sleep and psychological state, encouraging patients to express their true emotions, mentally preparing patients to face negative events with a peaceful attitude, and strengthening their optimism.

High quality of life related to functional role and global health status can enhance spiritual wellbeing. In contrast, the functional role domain score and global health status score were predictive of greater spiritual wellbeing. More than 60% of these patient were unable to perform persistent physical activities due to advanced stage disease[24], which can interfere with family life and social activities, thereby provoking negative emotions. The difficulties in long cycles of treatment and the unpredictable health outcome may cause substantial anxiety, leading to negative emotions, reluctance to communicate with others, and ultimately loss of faith and meaning in life. Patients with high social support were more inclined to welcome alternative opinions and enjoy the companionship of others to relieve stress, find peace of mind, and better adapt to life challenges. Therefore, medical staff should provide comprehensive and individualized spiritual care aiming to assist and encourage patients to positively accept and face negative events through disease cognition, psychological counseling, and life review.

The symptom domain of quality of life negatively affects spiritual wellbeing, suggesting that severe symptoms and concomitant poor quality of life can degrade spiritual wellbeing. This was consistent with the findings of Du et al[25], who also found that most PDAC patients treated with chemotherapy developed symptoms such as fatigue (68%) and insomnia (52%), which may have persisted during the course of treatment[26]. Patients with chronic fatigue were prone to express negative emotions, while discomfort from cyclic chemotherapy and chronic disease pain aggravated insomnia and lowered life expectations[27,28]. Consequently, medical staff should closely monitor adverse symptoms such as fatigue and insomnia to alleviate discomfort and improve life expectations, possibly via family guidance and mindfulness meditation.

This study had several limitations. Most patients were from southwestern China (Chongqing) and so this may not be a nationally representative sample. Future studies will expand the sample size and evaluate the effects of specific religious beliefs on the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients receiving chemotherapy.

Education level, health insurance category, symptom domain, functional role domain and global health status were the main factors influencing spiritual wellbeing among PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy. Individualized spiritual care regimens can be formulated through life care, behavioral therapy, mindfulness meditation, cognitive interview, and life review among other strategies.

Identifying the core factors influencing spiritual wellbeing of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients undergoing chemotherapy and formulating individualized spiritual care regimens can improve quality of life among this patient group. However, there have only been a few small studies of the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy. The core factors influencing spiritual wellbeing in this clinical population are still unclear. Therefore, this study was designed to identify factors influencing the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy.

This study was designed to investigated the spiritual wellbeing status and identify factors influencing the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy. To draw attention to the spiritual health of patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing chemotherapy and formulate individualized spiritual care regimens.

This study was designed to investigated the spiritual wellbeing status and identify factors influencing the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy. This study found that effective measures to mitigate anxiety and increase quality-of-life-related role functioning, emotional guidance, cognition of disease, social function, and life education may enhance spiritual wellbeing. Individualized spiritual care regimens can be formulated through life care, behavioral therapy, mindfulness meditation, cognitive interview, and life review among other strategies.

The research method of this study was a questionnaire survey. Prior to the questionnaire survey, all investigators received standardized training to guarantee the objectivity and accuracy of data collection. The questionnaire included a general information questionnaire, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being 12 Item Scale, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 and Zung’s Self-rating Anxiety Scale. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0. P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant for all tests.

This study investigated the spiritual wellbeing of Chinese patients with PDAC undergoing chemotherapy and analyzed its influencing factors for the first time. This study found that individualized spiritual care regimens can be formulated through life care, behavioral therapy, mindfulness meditation, cognitive interview, and life review among other strategies. This study had limitations. Most patients were from southwestern China (Chongqing), so this may not be a nationally representative sample. Future studies will expand the sample size and evaluate the effects of specific religious beliefs on the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients receiving chemotherapy.

Spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients treated with chemotherapy was in the mid-range, and individual differences in spiritual wellbeing related to demographics and clinical status. Anxiety and symptom severity markedly disrupted the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients undergoing chemotherapy, whereas a sustained functional role and good global health status related to quality of life promoted spiritual wellbeing. This study provides a theoretical basis for formulating individualized spiritual care regimens.

Future studies will expand the sample size and evaluate the effects of specific religious beliefs on the spiritual wellbeing of PDAC patients receiving chemotherapy.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mancini AD, United States; Meaney MJ, Canada S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Pancreatic Surgery Group; Surgical Society of Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer in China (2021)]. Zhonghua Xiaohua Waike Zazhi. 2021;20:713-729. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Jimenez-Fonseca P, Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ, Carmona-Bayonas A, Beato C, García T, Muñoz MDM, Ramchandani A, Ghanem I, Rodríguez-Capote A, Jara C, Calderon C. The mediating role of spirituality (meaning, peace, faith) between psychological distress and mental adjustment in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1411-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xiao H, Chen X, Cai G. [Spiritual Care]. Taipei: Hua Xing Publishing Press, 2009: 104-156. |

| 4. | Wang YN. [Spiritual Health Level of Patients with Thyroid Papillary Carcinoma After Endoscopic Resection and Its Influencing Factors]. Henan Yixue Yanjiu. 2021;30:6833-6836. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Chen P, Zhou HQ. [Study on the impact of spiritual nursing on the mental state, quality of life and spiritual needs of patients with pancreatic cancer under the model of life return]. Xunzheng Huli. 2022;8:371-377. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Chen P, Zhou H, Su X. [Effect evaluation of spiritual nursing on spiritual health level, cancer-induced fatigue and sleep quality in patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy]. Huli Shijian Yu Yanjiu. 2022;19:277-279. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Li Z. [Research methods in nursing]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House Co, LTD, 2012. |

| 8. | Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology. 1999;8:417-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Liu XY, Wei D, Shen YY, Cheng QQ, Liang S, Xu XH, Zhang M. [Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-spiritual well-being in cancer patients]. Zhonghua Huli Zazhi. 2016;51:1085-1090. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in RCA: 11464] [Article Influence: 358.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2251] [Cited by in RCA: 2742] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xue G, Zhang Y, Qu J. [Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis of Spiritual Health and Its Influence Factors of Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: A 190-case Study]. Huli Xuebao. 2019;26:32-36. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Liu ZF, Tang LQ, Chen CH, Qing W, Zhang Z, Long L. [Spiritual well-being level and its influencing factors in patients with maintenance peritoneal dialysis]. Guangxi Yixue. 2022;44:832-837. |

| 14. | Liu YP, Zhang JJ, Ren Y, Tian Q, Liu HQ. [Trends of disease burden of pancreatic cancer in China, 1990-2019]. Xiandai Yufang Yixue. 2022;49:3079-3085, 3110. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Ye N. [Effects of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on short-term clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer]. M.Sc. Thesis, Shandong University. 2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Zeng H, Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Ji JS, Zou X, Xia C, Sun K, Yang Z, Li H, Wang N, Han R, Liu S, Mu H, He Y, Xu Y, Fu Z, Zhou Y, Jiang J, Yang Y, Chen J, Wei K, Fan D, Wang J, Fu F, Zhao D, Song G, Jiang C, Zhou X, Gu X, Jin F, Li Q, Li Y, Wu T, Yan C, Dong J, Hua Z, Baade P, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Changing cancer survival in China during 2003-15: a pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e555-e567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 795] [Cited by in RCA: 977] [Article Influence: 139.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Liu M, Liu J, Zhang L, Xu W, He D, Wei W, Ge Y, Dandu C. An evidence of brain-heart disorder: mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia regulated by inflammatory cytokines. Neurol Res. 2020;42:670-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lv X, Rui ZH, An XL, Huang GP, Hao Y. [Relationship between authentic self, self-esteem and youth mental health: Mediation model moderated by gender]. Zhongguo Jiankang Xinlixue Zazhi. 2023;31:1-9. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Lin J. [Investigation on spiritual care needs of cancer patients and nursing intervention strategies]. Huli Yu Shijian. 2019;16:61-62. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Liu Y. [Investigation on spiritual care needs of advanced cancer patients and study on therapeutic intervention]. M.Sc. Thesis, Nanhua University. 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Nie XF, Shi T, Lei WW, Li FL, Chen QS, Xu JH. [Analysis of the current situation and influencing factors of the needs of nurses to provide spiritual care in patients with laryngeal cancer]. Huli Shijian Yu Yanjiu. 2022;19:1768-1772. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Ren Y. [Effect of spiritual care on negative emotions and prognosis of patients with gastrointestinal cancer pain]. Dangdai Hushi. 2019;26: 73-75. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Chen HX, Pei JH, Nan RL, Lu JJ, Dou XM. [The status quo of anticipatory grief among patients with advanced gastric cancer and its influencing factors]. Jiafangjun Huli Zazhi. 2021;38:11-15. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Sun YK, Su AH. [Research advances in immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer]. Zhongguo Yixue Qianyan Zazhi. 2022;14:36-40. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Du G, Ding L. [The relevant research of final stage cancer patients' weary feeling and hope feeling]. Guoji Hulixue Zazhi. 2011;30:24-26. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Wang LG, Yang L, Wang L, Liang XQ, Xue H, Chen LY, Qiu XH, Huang BC, Sheng X. [Study on methodological and reporting quality evaluation of RCTs in moxibustion treatment of cancer-related fatigue]. Xunzheng Huli. 2022;8:2699-2706. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Yang X, Ma Q, Dong QQ, Song QX. [Effect of Acupuncture and Moxibustion Combined with Auricular Acupoint Injection on Insomnia, Pain and Quality of Life after Radical Resection of Pancreatic Cancer]. Guangming Zhongyi. 2021;36:2406-2408. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Liu XY, Yun J, Wu Q, Chen Q. [Meta-analysis of the correlation between cancer-related fatigue and hope of patients with cancer]. Mudanjiang Yixueyuan Xuebao. 2022;43:82-86. [DOI] [Full Text] |