Published online Feb 4, 2016. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v5.i1.12

Peer-review started: July 24, 2015

First decision: September 28, 2015

Revised: October 7, 2015

Accepted: November 24, 2015

Article in press: November 25, 2015

Published online: February 4, 2016

Processing time: 185 Days and 14.1 Hours

We have tried in a recently published systematic review (World J of Surg 2014; 38: 322-329) to study the educational value of advanced trauma life support (ATLS) courses and whether they improve survival of multiple trauma patients. This Frontier article summarizes what we have learned and reflects on future perspectives in this important area. Our recently published systematic review has shown that ATLS training is very useful from an educational point view. It significantly increased knowledge, and improved practical skills and the critical decision making process in managing multiple trauma patients. These positive changes were evident in a wide range of learners including undergraduate medical students and postgraduate residents from different subspecialties. In contrast, clear evidence that ATLS training reduces trauma death is lacking. It is obvious that it is almost impossible to perform randomized controlled trials to study the effect of ATLS courses on trauma mortality. Studying factors predicting trauma mortality is a very complex issue. Accordingly, trauma mortality does not depend solely on ATLS training but on other important factors, like presence of well-developed trauma systems including advanced pre-hospital care. We think that the way to answer whether ATLS training improves survival is to perform large prospective cohort studies of high quality data and use advanced statistical modelling.

Core tip: We recommend teaching advanced trauma life support (ATLS) courses for doctors who may treat multiple trauma patients in their setting. Large prospective cohort studies of high quality data are needed to evaluate the impact of ATLS training on trauma death rates and disability.

- Citation: Abu-Zidan FM. Advanced trauma life support training: How useful it is? World J Crit Care Med 2016; 5(1): 12-16

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v5/i1/12.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v5.i1.12

Professor Fikri M Abu-Zidan (Figure 1) is a Consultant Trauma and Acute Care Surgeon who gained his MD from Aleppo University, Syria, in 1981. He was awarded the Fellowship of Royal College of Surgeons of Glasgow, Scotland in 1987. He achieved his PhD in Trauma and Disaster Medicine from Linkoping University, Sweden in 1995 and then obtained his Postgraduate Diploma of Applied Statistics from Massey University, New Zealand, in 1999. He worked as a surgeon at Mubarak Al-Kabeer Teaching Hospital in Kuwait from 1983-1993, as a Trauma Research Fellow at Linkoping University, Sweden, from 1993-1995, as a Senior Research Fellow at Auckland University, New Zealand from 1996-2001; and as a Trauma Fellow at Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Australia, during 2001. He is at present a Professor of Surgery at the Department of Surgery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates (UAE) University, United Arab Emirates. He has contributed to more than 270 publications in refereed international journals. Professor Abu-Zidan is a well-respected international Judge, invited speaker, and visiting Professor at numerous international meetings with more than 350 presentations and invited lectures. At present, Professor Abu-Zidan is serving as the Statistical Consultant for World Society of Emergency Surgery, Statistical Consultant for World Journal of Emergency Surgery, Statistics Editor of Hamdan Medical Journal, and as an Invited Editor, member of Editorial board, and reviewer for several international journals. His clinical experience includes treating war injured patients during the Second Gulf War (1990). He has been promoting the use of Point-of-Care Ultrasound for more than twenty five years and he is considered a World Leader in this area. Furthermore, he is an international expert on trauma experimental methodology with particular expertise in developing novel clinically relevant animal models. He played an important role in establishing experimental surgical research in Auckland University, New Zealand which subsequently developed into a strong successful PhD Program. Professor Abu-Zidan has received numerous national and international awards for clinical, research and educational activities.

Trauma is a leading cause of death and disability all over the world. Trauma management can be improved by implementing a trauma system that includes injury prevention, education, pre-hospital care, transportation, hospital care, and rehabilitation[1]. If properly implemented, trauma systems can reduce mortality of severe trauma patients by at least 15%[2]. Training physicians to manage multiple trauma patients is an essential part of developing proper trauma systems. The primary end point of any clinical educational activity is its impact on improving health care. Our trauma group has been extensively involved in teaching advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and focused assessment sonography courses for the last 15 years[3-6]. These courses are time consuming and need extensive resources and manpower. ATLS is one of the most common courses taught worldwide. In an evidenced-based era, it is legitimate to question the educational and clinical value of these courses. We tried in a recently published systematic review to study the educational value of ATLS courses and whether they improved survival of multiple trauma patients[7]. This article summarizes what we have learned and reflects on future perspectives in this area.

The ATLS course was established in 1976 by Dr James Styner in United States after a tragic private family plane crash. Dr Styner was not happy with the level of health care given to his family members. He developed ATLS so as to improve the management of multiple trauma patients in rural areas. This course was adopted by the American College of Surgeons and quickly spread worldwide[8,9]. To date it has been taught to more than one million doctors in more than 60 countries[10]. It is accepted as a standard protocol for the initial care of trauma patients in many trauma centers worldwide[11,12].

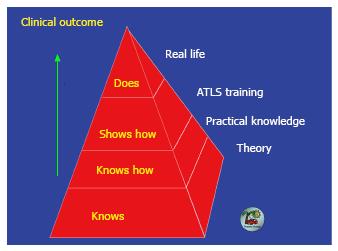

ATLS is a very demanding two/three full days course that uses different adult learning approaches[13] including interactive didactic teaching, simulated clinical cases (Figures 2 and 3), practical skill stations (Figure 4), and group discussions[14]. Following ATLS training, non-surgical physicians should be able to successfully manage severe trauma patients[15]. The interactive approach for teaching ATLS improves clinical assessment of trauma patients. It is more enjoyable and rewarding compared with classical teaching[16,17]. It actively involves students in discussions, encourages them to ask more questions, and gives direct feedback. ATLS simulations place candidates under stress in clinical scenarios so that they can later make critical decisions in a real world environment. ATLS aims high to reach the top layer of Miller’s educational pyramid (“does”) (Figure 5)[18,19]. Physicians are observed performing certain procedures and applying them in simulated clinical scenario. It is important to stress that the real value of any educational medical activity is measured by its clinical benefit for patients in real life.

We started teaching ATLS in UAE in 2004. More than 2000 doctors have taken this course in UAE[20]. The majority of participants in UAE were residents (44.8%), and specialists (43.7%). Critical care physicians and anaesthetists constituted 11% of all participants of ATLS courses in UAE. Interestingly, critical care physicians showed similar theoretical (P = 0.89) and practical knowledge (P = 0.99) when compared with surgeons during ATLS courses in UAE[4].

We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, and the Cochrane databases for articles studying the educational outcomes of ATLS courses and their impact on trauma death. Articles published during the period 1966-2012 were studied. Out of 384 papers, 23 met our selection criteria. Ten original papers investigated the effects of ATLS courses on knowledge and practical skills, six original papers studied the time needed to lose practical skills gained by ATLS courses, and seven original papers studied the impact of ATLS courses on trauma death. I critically appraised these papers regarding their research methodology and statistical analysis in this systematic review[7]. We used The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network handbook to grade the level of evidence of the papers[21]. Furthermore, we used the United States preventive Services Task Force grading system to grade overall quality of evidence[22].

ATLS significantly increases knowledge of trauma management, improves practical skills, organization of trauma management, and identification of management priorities (level I evidence: Evidence obtained from at least one properly randomized controlled trial). The gained knowledge and skills start to decline gradually 6 mo after the course (level II-1 evidence: Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization) and reach maximum decline after 2 years. Participants keep the gained organizational skills and identification of management priorities up to 8 years after taking the course. Teaching ATLS courses using the interactive approach significantly improved the practical skills compared with the old classical teaching (Level I evidence)[7].

Knowledge and practical skills gained by ATLS participants decline over time if these skills are not utilized. This supports the need for re-certification. We are of the opinion that ATLS re-certification should be under taken every four years so as to update candidates with recent advances in trauma management. Trauma management continuously changes depending on new scientific evidence that leads to modification of recommendations and guidelines.

Medical literature does not show accumulative evidence that ATLS training reduces trauma death. All seven studies addressing the effects of ATLS training on trauma death were retrospective except one which was a prospective cohort study. Five of these studies did not show any effect of ATLS training on trauma death, one study showed significant improvement, while another showed a worse outcome of trauma patients who were managed by ATLS certified doctors[7].

It is recommended that at least two independent researchers should do the literature search in systematic reviews and at least two methodologists should critically appraise the selected papers. This would reduce both search bias and evaluator bias. What worked for us during the search stage is that ATLS or “Advanced Trauma Life Support” is a very specific term. Furthermore, MEDLINE and PubMed have the ability to automatically search for alternative terms. This would have reduced the search bias. One of the major limitations in performing systematic reviews in developing countries is lack of research methodologists. The systematic review discussed[7] was critically appraised by only one evaluator which is definitely a limitation.

What assured us that our evaluation was proper is that a very recent Cochrane database systematic review that was published a few months after our paper had the same research question. This systematic review produced exactly the same results and conclusions as ours[23].

Our recently published systematic review has shown that ATLS training is very useful from an educational point view. It significantly increased knowledge, and improved both practical skills and the critical decision making process in managing multiple trauma patients. These positive changes were evident in a wide range of learners including undergraduate medical students and postgraduate residents from different subspecialties. In contrast, clear evidence that ATLS training reduces trauma death is lacking. We recommend teaching ATLS courses for those doctors who may treat multiple trauma patients in their setting. Large prospective cohort studies of high quality data are needed to evaluate the impact of ATLS training on trauma death rates and disability.

It is obvious that it is almost impossible to perform randomized controlled trials to study the effect of ATLS courses on trauma mortality simply because all conditions cannot be standardized. Studying factors predicting trauma mortality is a very complex issue. There are multiple confounders and logistics that prevent such experimental design. Accordingly, trauma mortality does not depend solely on ATLS training but on other important factors, like presence of well-developed trauma systems with advanced pre-hospital care. In a population based study from different counties in United States, Rutledge et al[24] found that the effects of ATLS training differed between different county clusters. This indicates that factors affecting mortality are more complex and pertain not only to ATLS training[24]. We think that the way to answer whether ATLS training improves survival is to perform large prospective cohort studies of high quality data and use advanced statistical modelling for that.

The author thanks Ms. Geraldine Kershaw, Lecturer, Medical Communication and Study Skills, Department of Medical Education, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, UAE University for language and grammar corrections.

P- Reviewer: Cotogni P, Lee TS, Mashreky SR, Trohman RG S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Hoyt DB, Coimbra R. Trauma systems. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:21-35, v-vi. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Celso B, Tepas J, Langland-Orban B, Pracht E, Papa L, Lottenberg L, Flint L. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006;60:371-378; discussion 378. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Abu-Zidan FM, Dittrich K, Czechowski JJ, Kazzam EE. Establishment of a course for Focused Assessment Sonography for Trauma. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:806-811. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Abu-Zidan FM, Mohammad A, Jamal A, Chetty D, Gautam SC, van Dyke M, Branicki FJ. Factors affecting success rate of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses. World J Surg. 2014;38:1405-1410. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Abu-Zidan FM, Freeman P, Mandavia D. The first Australian workshop on bedside ultrasound in the Emergency Department. N Z Med J. 1999;112:322-324. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Abu-Zidan FM, Siösteen AK, Wang J, al-Ayoubi F, Lennquist S. Establishment of a teaching animal model for sonographic diagnosis of trauma. J Trauma. 2004;56:99-104. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mohammad A, Branicki F, Abu-Zidan FM. Educational and clinical impact of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2014;38:322-329. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Collicott PE. Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS): past, present, future--16th Stone Lecture, American Trauma Society. J Trauma. 1992;33:749-753. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gwinnutt CL, Driscoll PA. Advanced trauma life support. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1996;13:95-101. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Drimousis PG, Theodorou D, Toutouzas K, Stergiopoulos S, Delicha EM, Giannopoulos P, Larentzakis A, Katsaragakis S. Advanced Trauma Life Support certified physicians in a non trauma system setting: is it enough? Resuscitation. 2011;82:180-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baker MS. Advanced trauma life support: is it adequate stand-alone training for military medicine? Mil Med. 1994;159:587-590. [PubMed] |

| 12. | van Olden GD, Meeuwis JD, Bolhuis HW, Boxma H, Goris RJ. Advanced trauma life support study: quality of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. J Trauma. 2004;57:381-384. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Carley S, Driscoll P. Trauma education. Resuscitation. 2001;48:47-56. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Carmont MR. The Advanced Trauma Life Support course: a history of its development and review of related literature. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:87-91. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Ben Abraham R, Stein M, Kluger Y, Rivkind A, Shemer J. The impact of advanced trauma life support course on graduates with a non-surgical medical background. Eur J Emerg Med. 1997;4:11-14. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Ali J, Adam RU, Josa D, Pierre I, Bedaysie H, West U, Winn J, Haynes B. Comparison of performance of interns completing the old (1993) and new interactive (1997) Advanced Trauma Life Support courses. J Trauma. 1999;46:80-86. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ali J, Adam R, Pierre I, Bedaysie H, Josa D, Winn J. Comparison of performance 2 years after the old and new (interactive) ATLS courses. J Surg Res. 2001;97:71-75. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65:S63-S67. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. The use of clinical simulations in assessment. Med Educ. 2003;37 Suppl 1:65-71. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Advanced Trauma Life Support. Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors, UAE Chapter. Available from: http://www.traumauae.com/. |

| 21. | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Key to evidence statements and grades of recommendations. SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer’s Handbook, Revised Edn, January 2008. Edinburgh 2011; 51 Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign50.pdf. |

| 22. | Berg AO, Allan JD. Introducing the third US Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:3-4. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Jayaraman S, Sethi D, Chinnock P, Wong R. Advanced trauma life support training for hospital staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:CD004173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |