Published online Jun 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.98791

Revised: December 11, 2024

Accepted: December 19, 2024

Published online: June 9, 2025

Processing time: 236 Days and 19.2 Hours

The global incidence of critical illness has been steadily increasing, resulting in higher mortality rates thereby presenting substantial challenges for clinical mana

Core Tip: Lymphocytes are essential effectors in the immune response to sepsis, contributing to both the initial defense against infection and the regulation of inflammation during the progression to chronic organ failure. One hallmark of sepsis is a profound disruption in lymphocyte homeostasis, that may lead to the development of an immunosuppressive state. Lymphocytes counts and derived variables show significant potential as prognostic markers in sepsis, offering insight into mortality risk and the likelihood of persistent organ dysfunction.

- Citation: Nedel W, Henrique LR, Portela LV. Why should lymphocytes immune profile matter in sepsis? World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(2): 98791

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i2/98791.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.98791

The immune system is premised on defending organisms from invaders and promoting healing of injuries. Its responses are broadly categorized into two mechanisms: Innate and adaptive immunity[1,2]. The innate response corresponds to the initial reaction, in which cells originating from the myeloid progenitor differentiate to halt the spread of harmful agents. Polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages play a central role in this phase, eliminating pathogens through phagocytosis[3]. Specialized innate immune cells, such as dendritic cells, further enhance the immune response by transforming into antigen-presenting cells after phagocytizing the antigen. These cells bridge innate and adaptive immunity by presenting antigens to lymphocytes, thereby initiating the adaptive immune response[1,3]. This enables lymphocytes to perform immune recognition, thereby distinguishing between inert endogenous components and harmful external agents and memorizing antigen patterns[1,2].

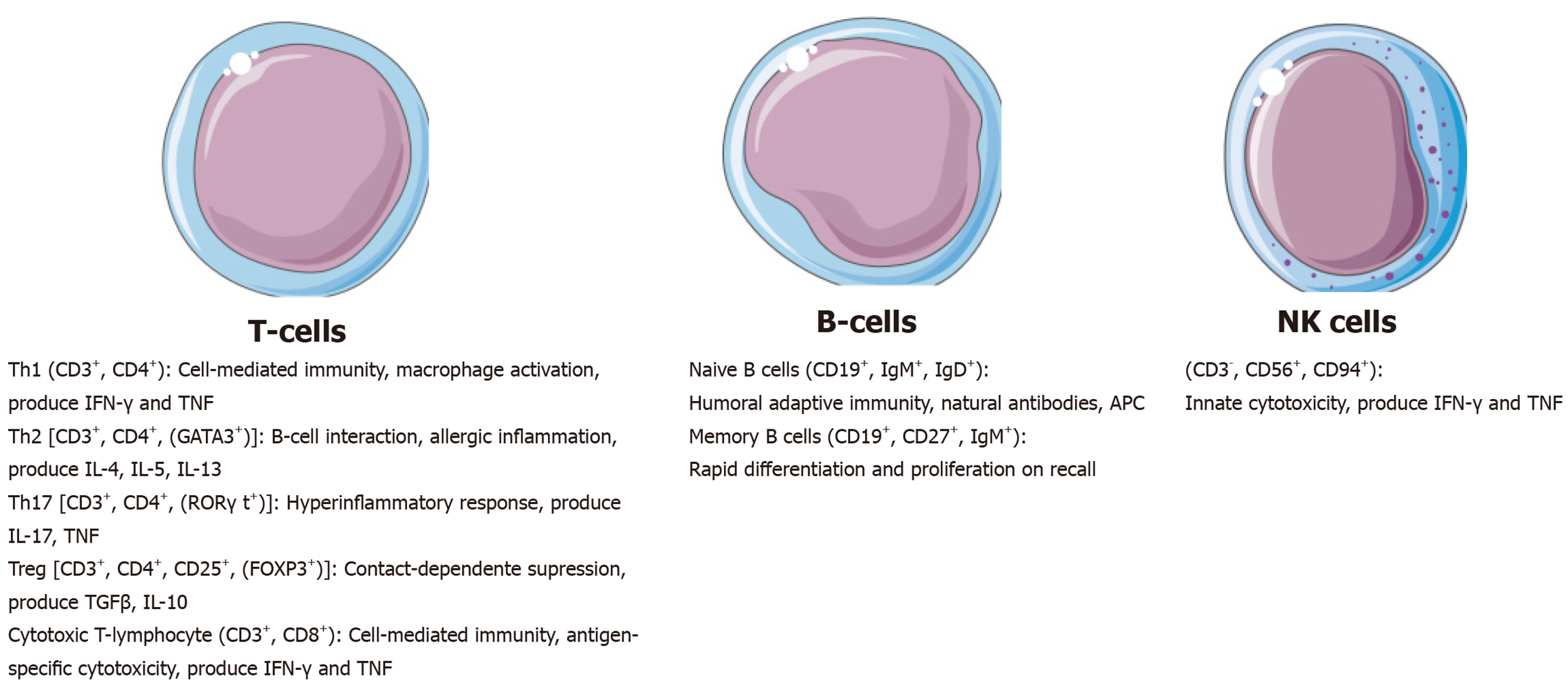

This review addresses the role of lymphocytes counts and derived parameters in the immune response, with a particular focus on their involvement in sepsis. Additionally, it discusses lymphocytes as clinical biomarkers and their emerging potential as therapeutic targets in sepsis management. Lymphocytes constitute approximately 40% of the white blood cell population and include B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells and their subtypes (Figure 1). B cells and T cells are critical components of the adaptive immune response system, mediating responses to bacterial and viral pathogens, through antibody production and cell-mediated immunity, respectively[4]. In the context of sepsis, lymphocytes play a pivotal role in orchestrating the host immune response during both the acute and chronic phases of the syndrome[1]. Importantly, the lymphocytic response to sepsis may present distinct phenotypic profiles that are often associated with different clinical outcomes[4]. These profiles are influenced by the stage of the immune response - whether early or late - and are characterized by differences in lymphocyte proliferation, the expression of immunity-related proteins, and the secretion of signaling molecules. These cellular phenotypic transitions depend on metabolic plasticity to meet the substantial energy demands associated with immune activation, proliferation, and effector functions[2].

Sepsis is a global health priority[5] and is associated with a high mortality rate, even in middle-income countries[6] and high-income countries[7]. Despite different definitions over the last few decades, sepsis is best defined as a syndrome shaped by pathogens and host factors in a dysregulated systemic host response[8]. It is regulated by inflammatory effectors such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1, which modulate cellular responses and influence patients’ clinical outcomes[9]. Therefore, sepsis can potentially interfere with the host immune system and result in drastic changes[10]. During the first 24 hours - 48 hours following sepsis onset, the immune response is dominated by a pro-inflammatory burst, characterized by robust activation of cytokine pathways. Beyond this acute phase, the immune system undergoes a shift toward an anti-inflammatory state, often described as compensatory or maladaptive[11,12]. This transition can compromise immune surveillance and contribute to immune dysfunction.

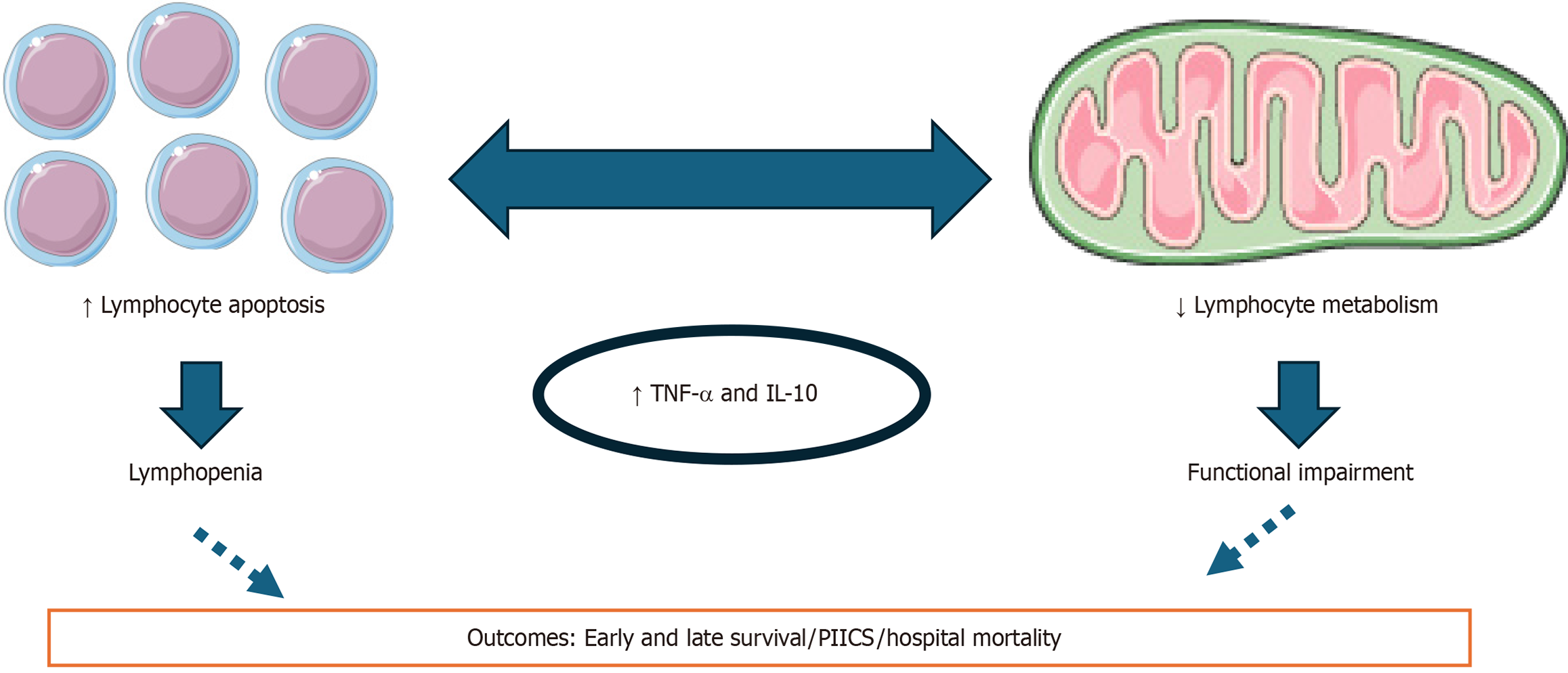

One hallmark of sepsis is a profound disruption in lymphocyte homeostasis, characterized by a significant reduction in lymphocyte counts, termed sepsis-induced lymphopenia. This may lead to the development of an immunosuppressive state, predisposing individual patients to secondary infections induced by low pathogenicity invaders thereby exacerbating patient morbidity and delaying recovery[9]. This depletion affects CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells, resulting in impaired lymphocyte functionality and contributing to immune paralysis. The duration of immunoparalysis needs to be hampered since it contributes to increased morbidity associated with sepsis[11,13]. Therefore, lymphocytes phenotype in sepsis may transit through states of acute response, persistent pro-inflammatory signaling to immunosuppression. Both quantitative and qualitative disturbances in lymphocytes have been observed across these states[14]. Indeed, a reduced lymphocyte count combined with metabolic dysregulation can further disrupt the crosstalk between the adaptive and innate immune systems, undermining the coordinated response required to resolve injury effectively[15,16].

The use of inflammatory biomarkers for prognostic and therapeutic assessments in sepsis has gained significant attention. Biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, IL-1β, and IL-6 are widely studied but not always accessible in clinical practice, particularly in middle- and low-income countries. This underscores the requirement of inexpensive, easy-to-perform, and reproducible biomarkers to aid clinical decision-making in sepsis management[17,18]. Lymphocyte-derived variables have emerged as promising biomarkers in recent years, providing insights into both acute injury and the progression of chronic sepsis. These variables can be derived from routine peripheral blood samples, and include total lymphocyte counts and ratios of lymphocytes to other immune cells (e.g., neutrophils and monocytes) or immune-related molecules (e.g., albumin and high-density lipoprotein). For instance, lymphopenia - defined as an absolute circulating lymphocyte count < 1000 cells/mm³ -has been associated with worse prognosis in sepsis, with derived ratios like the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) providing additional read-out of patients with worse prognosis[4,19].

Several studies in different countries and subgroups of intensive care unit (ICU) patients have demonstrated strong associations between lymphopenia, its derived markers, and unfavorable clinical outcomes (Table 1)[20-32]. In a large Taiwanese database, it was found that an early lymphopenia was linked to increased one-year mortality in critically ill surgical patients, with this association remaining robust after advanced statistical adjustments such as propensity score matching[33]. Similarly, elevated NLR levels have been correlated with higher mortality in ICU patients[34], and the persistence of lymphopenia has been tied to worse outcomes, including increased risk of nosocomial infections, acute kidney injury, and 28-day mortality[35,36]. Both the monocyte-lymphocyte ratio and NLR showed accurate performance as biomarkers[35]. The prognostic value of lymphocyte counts and ratios extends beyond traditional ICU settings. For instance, in the context of corona virus infectious disease-2019, elevated NLR has been predictive of disease severity, prolonged ICU stays, and mortality[37,38]. Other ratios, such as the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-to-C-reactive protein ratio, have shown promise as moderate predictors of septic shock progression during prolonged ICU stays[39-41].

| Ref. | Population | Variable measured | Outcome |

| Biyikli et al[20] | Adult patients older than 65 years with sepsis or septic shock in emergency admission | Platelet-lymphocyte ratio | Platelet-lymphocyte ratio was not associated with 30-day mortality (207.6 in non-survivors vs 168.3 in survivors) |

| Djordjevic et al[21] | Critically ill injured patients admitted to surgical ICU | PLR, MLR, NLR | There was no difference in the biomarkers regarding hospital mortality in septic trauma patients (8.5 in non-survivors vs 9.6 in survivors) |

| Gharebaghi et al[22] | Critically-ill patients with sepsis due to gram-negative pathogens | Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio | Patients who deceased had increased values of NLR in day 2 (14.9 vs 9.3) and in day 3 of ICU admission (17.2 vs 9.1), but not at day 1 (13 vs 9.8) |

| Goda et al[23] | Neurosurgical critically ill patients with cathteter-associated urinary tract infections or central line-associated bloodstream infections | Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio | An increased NLR was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in central-line associated bloodstream infections (7.29 in non-survivors vs 4.46 in survivors) |

| Guo et al[24] | Critically ill patients with sepsis, from MIMIC-IV database | Neutrophil + mono | An increased NMLR is associated with increased 30-day mortality (12.24 non-survivors vs 8.71 in survivors) |

| Hsu et al[25] | Critically ill cirrhotic patients with septic shock | LMR and NLR | Non-survivors had increased NLR (13 vs 10.3) and decreased LMR (1.1 vs 2.3) when compared with survivors |

| Li et al[26] | Critically ill septic shock patients | NLR | NLR at day 3 and delta NLR (day 3 - day 1), but not NLR at day 1 were associated with 28-day mortality, in univariate and multivariate analysis |

| Liang et al[27] | Critically ill patients with bloodstream infections | NLR | Delta NLR (NLR 48 hours - NLR at 0 hour) were higher in patients with shock |

| Liu et al[28] | Critically ill patients with sepsis, from MIMIC-IV database | LHR | Low values of LHR were associated with 90-day mortality |

| Lorente et al[29] | Critically ill patients with sepsis | NLR | Increase in NLR at day 1, day 4 and day 8 were associated with 30-day mortality, when controlled for SOFA score and lactate at this time intervals |

| Sari et al[30] | Critically ill patients with sepsis | NLR | NLR at day 1 of sepsis is not associated with ICU mortality. At day 3, NLR greater than 15 is strongly associated with mortality |

| Wu and Qin[31] | Critically ill patients with sepsis | NLR, PLR, MLR | There was no difference between variables measured at baseline in survivors and non-survivors at 28-days post ICU admission |

| Xiao et al[32] | Adult septic patients from MIMIC-IV database | N/LP | High and middle terciles of N/LP at baseline were associated with an increase in the incidence of septic AKI (HR 1.3 and 1.2, respectively), as compared with the lower tercile |

Sepsis-induced lymphopenia involves apoptotic mechanisms mediated by death receptor activation and mitochondrial pathways in lymphocytes[39-41]. This reduction is particularly significant in CD8+ T cells, with survivors of septic shock showing recovery of these cell counts after five days post-ICU admission[42]. Decreases in T-cell subpopulations (CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+) and B cells have been associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infections and diminished immunoglobulin M production[43,44]. However, the functional implications of lymphocyte subclasses remain underexplored, necessitating further investigation to refine their prognostic value and therapeutic target potential.

The impact of lymphopenia varies across the sepsis timeline (Figure 2). At sepsis onset, lymphopenia may not always correlate with 28-day mortality, but resolution of lymphopenia by day 4 has been linked to improved outcomes, even after adjusting for confounders[45]. Conversely, persistent lymphopenia from ICU admission to day 3 significantly increases the risk of secondary infections and 28-day mortality[46]. These findings suggest that lymphocyte trajectories during critical illness, particularly persistent lymphopenia, may serve as an accurate biomarker for short-term mortality, chronic critical illness development, and sepsis progression to septic shock[26,47]. When compared with the non-lymphopenic group, patients with sepsis and lymphopenia more frequently required ICU admission, had a longer hospital length of stay, and presented with a higher rate of in-hospital, and 30-day mortality[35,46,48]. Despite these promising findings, the clinical applicability of lymphocyte-derived biomarkers remains limited by inconsistencies in cutoff definitions for persistent lymphopenia, which range from 760 cells/μL to 1000 cells/μL across studies[35]. Additionally, while lymphopenia is associated with 90-day mortality and rehospitalization, its predictive accuracy for these outcomes is modest[49]. Larger, multicenter studies are needed to validate these findings and explore the implications of lymphopenia on clinically meaningful outcomes beyond mortality, including functional recovery and quality of life in different patient subgroups.

Sepsis remains a leading cause of mortality, with most deaths occurring within 72 hours of diagnosis, underscoring the importance of early recognition and intervention to improve survival rates[11]. However, some patients progress to a state of persistent critical illness, characterized by worsening or unresolved multiple organ failure and a heightened risk of unfavorable outcomes. Even after surviving the acute phase of sepsis, patients often endure prolonged ICU stays and remain vulnerable to secondary infections. This condition, now termed persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PIICS), is associated with substantial clinical, economic, and social burdens[50]. PIICS manifests as long-term dysfunction across multiple systems, including neurocognitive, muscular, respiratory, renal, and cardiovascular functions, often leading to lasting functional impairment. A defining feature of immunosuppression in PIICS is lymphopenia, specifically a lymphocyte count below 800 cells/μL. During sepsis, a compensatory anti-inflammatory response mediated by cytokines such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor beta counterbalances the initial pro-inflammatory cascade driven by IL-6 and IL-1[51]. While this response may mitigate tissue damage, it can also induce T-cell exhaustion and expand regulatory T-cell (Treg) populations, a subset of immunomodulatory CD4+ T cells that suppress immune responses to control inflammation[52,53]. Tregs play a dual role in perpetuating persistent inflammation and immunosuppression, impairing the host’s ability to resolve infections or respond to new threats[53,54].

Interestingly, the dysregulated expression of IL-6, IL-1, and IL-10 in sepsis has been shown to interfere with lymphocyte metabolism[55]. Persistent inflammation further disrupts mitochondrial function diminishing bioenergetic capacity and exacerbating immunoparalysis[56]. The mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction impairs adenosine triphosphate support in the presence of a hypercatabolic state, thereby undermining the appropriate immune function[56]. This imbalance sustains a vicious cycle of unresolved inflammation, hypercatabolism, and progressive lymphocyte-mediated immunosuppression or immune exhaustion. Sepsis-induced immunoparalysis involves multiple mechanisms within the adaptive immune response, including lymphocyte apoptosis, diminished antigen presentation, impaired antigen-driven proliferation, increased suppressive Treg populations, and T-cell exhaustion[11]. While studies recognized that both lymphopenia and reduced T-cell functionality have been strongly associated with adverse outcomes[10] the precise relationship between these variables requires further investigation (Figure 3). Nowadays, lymphopenia is a hallmark of chronic critical illness[57], especially when it occurs alongside PIICS[58]. This persistent immunosuppressive state contributes to prolonged disease courses and underscores the need for targeted interventions to restore lymphocyte function and mitigate long-term complications in sepsis survivors.

Recent findings have highlighted immunostimulatory therapies as novel strategies to restore host defense in sepsis and prevent opportunistic infections[59]. Among these, IL-7 stands out as a promising candidate for addressing sepsis-induced T-lymphocyte immune dysfunction. IL-7 has demonstrated the ability to enhance T-cell survival and fun

To date, two clinical trials have specifically assessed recombinant human IL-7 in septic patients with lymphopenia. In a phase II randomized controlled trial, Francois et al[60] observed a 3-fold to 4-fold sustained increase in lymphocyte counts, including a rise in circulating CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, without inducing cytokine storms, exacerbating inflammation, or causing organ dysfunction. A more recent trial also reported significant increases in absolute lymphocyte counts (including both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets) with IL-7 administration compared to placebo[14]. Both studies confirmed the safety profile of IL-7, though intravenous administration was associated with transient fever and respiratory distress, adverse effects not observed with intramuscular administration[14]. It is worth noting that these trials were not designed to evaluate key clinical outcomes such as mortality, length of hospital stay, or days free from organ support. Consequently, the long-term benefits of IL-7, including its impact on reinfections, rehospitalizations, and non-infectious complications, remain uncertain. Further research is needed to determine the specific patient populations most likely to benefit, such as those with lymphopenic sepsis at admission vs patients with persistent lymphopenia during their clinical course.

Lymphocytes play a central role in the host’s response to sepsis, both in the initial immune activation and in the pro

| 1. | Delves PJ, Roitt IM. The immune system. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:37-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 585] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parkin J, Cohen B. An overview of the immune system. Lancet. 2001;357:1777-1789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 803] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mantovani A, Garlanda C. Humoral Innate Immunity and Acute-Phase Proteins. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:439-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 65.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Finfer S, Venkatesh B, Hotchkiss RS, Sasson SC. Lymphopenia in sepsis-an acquired immunodeficiency? Immunol Cell Biol. 2023;101:535-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Font MD, Thyagarajan B, Khanna AK. Sepsis and Septic Shock - Basics of diagnosis, pathophysiology and clinical decision making. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104:573-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lobo SM, Rezende E, Mendes CL, Oliveira MC. Mortality due to sepsis in Brazil in a real scenario: the Brazilian ICUs project. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2019;31:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vincent JL, Jones G, David S, Olariu E, Cadwell KK. Frequency and mortality of septic shock in Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23:196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15803] [Cited by in RCA: 17223] [Article Influence: 1913.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Salomão R, Ferreira BL, Salomão MC, Santos SS, Azevedo LCP, Brunialti MKC. Sepsis: evolving concepts and challenges. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2019;52:e8595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Borken F, Markwart R, Requardt RP, Schubert K, Spacek M, Verner M, Rückriem S, Scherag A, Oehmichen F, Brunkhorst FM, Rubio I. Chronic Critical Illness from Sepsis Is Associated with an Enhanced TCR Response. J Immunol. 2017;198:4781-4791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Doughty L. Adaptive immune function in critical illness. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:274-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Arina P, Singer M. Pathophysiology of sepsis. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Bricker TL, Jarman SD 2nd, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Srivastava A, Swanson PE, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306:2594-2605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1072] [Cited by in RCA: 1273] [Article Influence: 90.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Daix T, Mathonnet A, Brakenridge S, Dequin PF, Mira JP, Berbille F, Morre M, Jeannet R, Blood T, Unsinger J, Blood J, Walton A, Moldawer LL, Hotchkiss R, François B. Intravenously administered interleukin-7 to reverse lymphopenia in patients with septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Oltean M. B-Cell Dysfunction in Septic Shock: Still Flying Below the Radar. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:923-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nedel WL, Kopczynski A, Rodolphi MS, Strogulski NR, De Bastiani M, Montes THM, Abruzzi J Jr, Galina A, Horvath TL, Portela LV. Mortality of septic shock patients is associated with impaired mitochondrial oxidative coupling efficiency in lymphocytes: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2021;9:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Póvoa P, Coelho L, Dal-Pizzol F, Ferrer R, Huttner A, Conway Morris A, Nobre V, Ramirez P, Rouze A, Salluh J, Singer M, Sweeney DA, Torres A, Waterer G, Kalil AC. How to use biomarkers of infection or sepsis at the bedside: guide to clinicians. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:142-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 71.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Barichello T, Generoso JS, Singer M, Dal-Pizzol F. Biomarkers for sepsis: more than just fever and leukocytosis-a narrative review. Crit Care. 2022;26:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 82.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fan LL, Wang YJ, Nan CJ, Chen YH, Su HX. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is associated with all-cause mortality among critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;490:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Biyikli E, Kayipmaz AE, Kavalci C. Effect of platelet-lymphocyte ratio and lactate levels obtained on mortality with sepsis and septic shock. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36:647-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Djordjevic D, Rondovic G, Surbatovic M, Stanojevic I, Udovicic I, Andjelic T, Zeba S, Milosavljevic S, Stankovic N, Abazovic D, Jevdjic J, Vojvodic D. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, and Mean Platelet Volume-to-Platelet Count Ratio as Biomarkers in Critically Ill and Injured Patients: Which Ratio to Choose to Predict Outcome and Nature of Bacteremia? Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:3758068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gharebaghi N, Valizade Hasanloei MA, Medizadeh Khalifani A, Pakzad S, Lahooti D. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with gram-negative sepsis admitted to intensive care unit. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2019;51:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goda R, Sharma R, Borkar SA, Katiyar V, Narwal P, Ganeshkumar A, Mohapatra S, Suri A, Kapil A, Chandra PS, Kale SS. Frailty and Neutrophil Lymphocyte Ratio as Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections or Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections in the Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit: Insights from a Retrospective Study in a Developing Country. World Neurosurg. 2022;162:e187-e197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Guo M, He W, Mao X, Luo Y, Zeng M. Association between ICU admission (neutrophil + monocyte)/lymphocyte ratio and 30-day mortality in patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hsu YC, Yang YY, Tsai IT. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio predicts mortality in cirrhotic patients with septic shock. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;40:70-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Li Q, Xie J, Huang Y, Liu S, Guo F, Liu L, Yang Y. Leukocyte kinetics during the early stage acts as a prognostic marker in patients with septic shock in intensive care unit. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liang P, Yu F. Predictive Value of Procalcitonin and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Variations for Bloodstream Infection with Septic Shock. Med Sci Monit. 2022;28:e935966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu W, Tao Q, Xiao J, Du Y, Pan T, Wang Y, Zhong X. Low lymphocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio predicts mortality in sepsis patients. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1279291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lorente L, Martín MM, Ortiz-López R, Alvarez-Castillo A, Ruiz C, Uribe L, González-Rivero AF, Pérez-Cejas A, Jiménez A. Association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in the first seven days of sepsis and mortality. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sarı R, Karakurt Z, Ay M, Çelik ME, Yalaz Tekan Ü, Çiyiltepe F, Kargın F, Saltürk C, Yazıcıoğlu Moçin Ö, Güngör G, Adıgüzel N. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of treatment response and mortality in septic shock patients in the intensive care unit. Turk J Med Sci. 2019;49:1336-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wu D, Qin H. Diagnostic and prognostic values of immunocyte ratios in patients with sepsis in the intensive care unit. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2023;17:1362-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Xiao W, Lu Z, Liu Y, Hua T, Zhang J, Hu J, Li H, Xu Y, Yang M. Influence of the Initial Neutrophils to Lymphocytes and Platelets Ratio on the Incidence and Severity of Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Double Robust Estimation Based on a Large Public Database. Front Immunol. 2022;13:925494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ho DT, Pham TT, Wong LT, Wu CL, Chan MC, Chao WC. Early absolute lymphocyte count was associated with one-year mortality in critically ill surgical patients: A propensity score-matching and weighting study. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0304627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ham SY, Yoon HJ, Nam SB, Yun BH, Eum D, Shin CS. Prognostic value of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume/platelet ratio for 1-year mortality in critically ill patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jiang J, Du H, Su Y, Li X, Zhang J, Chen M, Ren G, He F, Niu B. Nonviral infection-related lymphocytopenia for the prediction of adult sepsis and its persistence indicates a higher mortality. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Vulliamy PE, Perkins ZB, Brohi K, Manson J. Persistent lymphopenia is an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill emergency general surgical patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016;42:755-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Li X, Liu C, Mao Z, Xiao M, Wang L, Qi S, Zhou F. Predictive values of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio on disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24:647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Martins PM, Gomes TLN, Franco EP, Vieira LL, Pimentel GD. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio at intensive care unit admission is associated with nutrition risk in patients with COVID-19. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46:1441-1448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Cao C, Yu M, Chai Y. Pathological alteration and therapeutic implications of sepsis-induced immune cell apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 954] [Cited by in RCA: 947] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hotchkiss RS, Osmon SB, Chang KC, Wagner TH, Coopersmith CM, Karl IE. Accelerated lymphocyte death in sepsis occurs by both the death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. J Immunol. 2005;174:5110-5118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chen R, Qin S, Zhu H, Chang G, Li M, Lu H, Shen M, Gao Q, Lin X. Dynamic monitoring of circulating CD8(+) T and NK cell function in patients with septic shock. Immunol Lett. 2022;243:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zhao J, Dai RS, Chen YZ, Zhuang YG. Prognostic significance of lymphocyte subpopulations for ICU-acquired infections in patients with sepsis: a retrospective study. J Hosp Infect. 2023;140:40-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dong X, Liu Q, Zheng Q, Liu X, Wang Y, Xie Z, Liu T, Yang F, Gao W, Bai X, Li Z. Alterations of B Cells in Immunosuppressive Phase of Septic Shock Patients. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:815-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Drewry AM, Samra N, Skrupky LP, Fuller BM, Compton SM, Hotchkiss RS. Persistent lymphopenia after diagnosis of sepsis predicts mortality. Shock. 2014;42:383-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Adrie C, Lugosi M, Sonneville R, Souweine B, Ruckly S, Cartier JC, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Schwebel C, Timsit JF; OUTCOMEREA study group. Persistent lymphopenia is a risk factor for ICU-acquired infections and for death in ICU patients with sustained hypotension at admission. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Pei F, Song W, Wang L, Liang L, Gu B, Chen M, Nie Y, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Guan X, Wu J. Lymphocyte trajectories are associated with prognosis in critically ill patients: A convenient way to monitor immune status. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:953103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Cilloniz C, Peroni HJ, Gabarrús A, García-Vidal C, Pericàs JM, Bermejo-Martin J, Torres A. Lymphopenia Is Associated With Poor Outcomes of Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia and Sepsis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Denstaedt SJ, Cano J, Wang XQ, Donnelly JP, Seelye S, Prescott HC. Blood count derangements after sepsis and association with post-hospital outcomes. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1133351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Voiriot G, Oualha M, Pierre A, Salmon-Gandonnière C, Gaudet A, Jouan Y, Kallel H, Radermacher P, Vodovar D, Sarton B, Stiel L, Bréchot N, Préau S, Joffre J; la CRT de la SRLF. Chronic critical illness and post-intensive care syndrome: from pathophysiology to clinical challenges. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12:58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Bergmann CB, Beckmann N, Salyer CE, Crisologo PA, Nomellini V, Caldwell CC. Lymphocyte Immunosuppression and Dysfunction Contributing to Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome (PICS). Shock. 2021;55:723-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Pugh AM, Auteri NJ, Goetzman HS, Caldwell CC, Nomellini V. A Murine Model of Persistent Inflammation, Immune Suppression, and Catabolism Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Gao YL, Yao Y, Zhang X, Chen F, Meng XL, Chen XS, Wang CL, Liu YC, Tian X, Shou ST, Chai YF. Regulatory T Cells: Angels or Demons in the Pathophysiology of Sepsis? Front Immunol. 2022;13:829210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cao C, Ma T, Chai YF, Shou ST. The role of regulatory T cells in immune dysfunction during sepsis. World J Emerg Med. 2015;6:5-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Nedel WL, Strogulski NR, Rodolphi MS, Kopczynski A, Montes THM, Portela LV. Short-Term Inflammatory Biomarker Profiles Are Associated with Deficient Mitochondrial Bioenergetics in Lymphocytes of Septic Shock Patients-A Prospective Cohort Study. Shock. 2023;59:288-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nedel W, Deutschendorf C, Portela LVC. Sepsis-induced mitochondrial dysfunction: A narrative review. World J Crit Care Med. 2023;12:139-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Stortz JA, Mira JC, Raymond SL, Loftus TJ, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Wang Z, Ghita GL, Leeuwenburgh C, Segal MS, Bihorac A, Brumback BA, Mohr AM, Efron PA, Moldawer LL, Moore FA, Brakenridge SC. Benchmarking clinical outcomes and the immunocatabolic phenotype of chronic critical illness after sepsis in surgical intensive care unit patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:342-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Zhou Q, Qian H, Yang A, Lu J, Liu J. Clinical and Prognostic Features of Chronic Critical Illness/Persistent Inflammation Immunosuppression and Catabolism Patients: A Prospective Observational Clinical Study. Shock. 2023;59:5-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | de Roquetaillade C, Monneret G, Gossez M, Venet F. IL-7 and Its Beneficial Role in Sepsis-Induced T Lymphocyte Dysfunction. Crit Rev Immunol. 2018;38:433-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Francois B, Jeannet R, Daix T, Walton AH, Shotwell MS, Unsinger J, Monneret G, Rimmelé T, Blood T, Morre M, Gregoire A, Mayo GA, Blood J, Durum SK, Sherwood ER, Hotchkiss RS. Interleukin-7 restores lymphocytes in septic shock: the IRIS-7 randomized clinical trial. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e98960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |