Published online Dec 9, 2024. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v13.i4.97145

Revised: September 4, 2024

Accepted: September 11, 2024

Published online: December 9, 2024

Processing time: 153 Days and 19.8 Hours

There is a substantial population of long-stay patients who non-emergently transfer directly from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) without an interim discharge home. These infants are often medically complex and have higher mortality relative to NICU or PICU-only admissions. Given an absence of data surrounding practice patterns for non-emergent NICU to PICU transfers, we hypothesized that we would encounter a broad spectrum of current practices and a high proportion of dissatisfaction with current processes.

To characterize non-emergent NICU to PICU transfer practices across the United States and query PICU providers’ evaluations of their effectiveness.

A cross-sectional survey was drafted, piloted, and sent to one physician representative from each of 115 PICUs across the United States based on membership in the PARK-PICU research consortium and membership in the Children’s Hospital Association. The survey was administered via internet (REDCap). Analysis was performed using STATA, primarily consisting of descriptive statistics, though logistic regressions were run examining the relationship between specific transfer steps, hospital characteristics, and effectiveness of transfer.

One PICU attending from each of 81 institutions in the United States completed the survey (overall 70% response rate). Over half (52%) indicated their hospital transfers patients without using set clinical criteria, and only 33% indicated that their hospital has a standardized protocol to facilitate non-emergent transfer. Fewer than half of respondents reported that their institution’s non-emergent NICU to PICU transfer practices were effective for clinicians (47%) or patient families (38%). Respondents evaluated their centers’ transfers as less effective when they lacked any transfer criteria (P = 0.027) or set transfer protocols (P = 0.007). Respondents overwhelmingly agreed that having set clinical criteria and standardized protocols for non-emergent transfer were important to the patient-family experience and patient safety.

Most hospitals lacked any clinical criteria or protocols for non-emergent NICU to PICU transfers. More positive perceptions of transfer effectiveness were found among those with set criteria and/or transfer protocols.

Core Tip: This is the first published study characterizing practice patterns of non-emergent neonatal intensive care unit to pediatric intensive care unit transfers, a growing subpopulation with high morbidity and mortality in the United States. Our results show these transfers were common, but most centers do not have standardized clinical criteria or transfer protocols. A wide variety of practices exist among those with set processes. An overwhelming majority of respondents endorsed that standardizing clinical criteria and transfer protocols are important for patient safety and the patient-family experience. Furthermore, respondents evaluated these transfers as more effective when standardization was in place, suggesting benefits of institutional attention to these processes.

- Citation: Cohen PD, Boss RD, Stockwell DC, Bernier M, Collaco JM, Kudchadkar SR. Perspectives on non-emergent neonatal intensive care unit to pediatric intensive care unit care transfers in the United States. World J Crit Care Med 2024; 13(4): 97145

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v13/i4/97145.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v13.i4.97145

The field of pediatrics is seeing an increase in children with chronic critical illness[1,2]. Previous surveys have estimated that chronically ill patients occupy anywhere from 25%-60% of pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) beds at a given time, 10% of whom are patients admitted to a hospital since birth without previous discharge home[3,4].

This subpopulation of PICU patients transferred from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is unique, with recent literature suggesting a high incidence of technology dependence and a higher relative mortality[5]. Concordantly, there is emerging work showing this population’s high utilization of healthcare resources[6,7]. These infants and their families are also abruptly faced with differences between NICUs and PICUs, including differences in clinical approaches to sedatives and ventilatory support, overall unit design and environmental stimuli, and communication around difficult decisions[8-10]. These contrasts underscore the impact that transferring care from the NICU to PICU can have on these patients and their families.

At present, little research exists to guide best practices in making non-emergent NICU to PICU transitions safe and seamless for patients, families, and healthcare providers. In some instances, sentinel safety events have prompted individual centers to develop processes and tools to facilitate transfer which have been subsequently well-received by care teams[8,11,12]. While there is currently no evidence characterizing practice patterns of NICU to PICU transfers in the United States, a survey of medical directors in Australia and New Zealand concerning the transfer of infants with chronic lung disease from NICUs to PICUs found that most centers proceeded without standard protocols, and only a quarter of centers had set criteria for transfer[13]. Thus, we aimed to characterize existing non-emergent NICU to PICU transfer practices in hospitals across the United States for the first time and gauge clinician perspectives of those practices’ effectiveness via cross-sectional survey.

The study sample included 115 hospitals with PICUs primarily from the PARK-PICU research network[14,15]. Additional centers were added by the research team based on membership in the Children’s Hospital Association and searching publicly available hospital and university electronic directories. Study information was sent to a single pediatric critical care physician (PARK-PICU Site PI or Medical Director) at each site, who could either participate directly or refer a colleague with more expertise in the subject matter. Only physicians in pediatric critical care medicine were eligible to complete the survey. Respondents were excluded if they endorsed a lack of sufficient knowledge on the subject via a screening question, or if they did not complete the survey’s questions regarding existing transfer practices. Only the first valid response from each institution was included.

The survey tool (Supplementary material) consisted of an English-language, web-based questionnaire hosted on REDCap. It was constructed after a literature search conducted with a medical librarian revealed only one previous study performed characterizing NICU to PICU transitions for a similar (though not equivalent) population of chronic lung disease infants in Australia[13]. Our survey tool was developed by study team members with experience in the transfer of NICU patients to the PICU, was reviewed and refined with the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Office of Evaluation and Assessment, and was piloted by pediatric critical care medicine physicians at multiple institutions prior to being distributed. Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board exemption was granted, but respondents still received study background information and consented electronically. The invitation was sent in August 2023, with monthly email reminders delivered prior to survey closure in November 2023.

Descriptive statistics consisted of counts and percentages for categorical variables and as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or means and SD for continuous variables. Advanced statistics were run as nonparametric statistical tests with a significance threshold of P ≤ 0.05. We performed logistic regression to examine the relationship between specific transfer steps, hospital characteristics, and effectiveness of transfer. All statistics were run using STATA (StataCorp; College Station, TX). Statistics were reviewed by the entire authorship team, multiple of whom have advanced biostatistics training and experience.

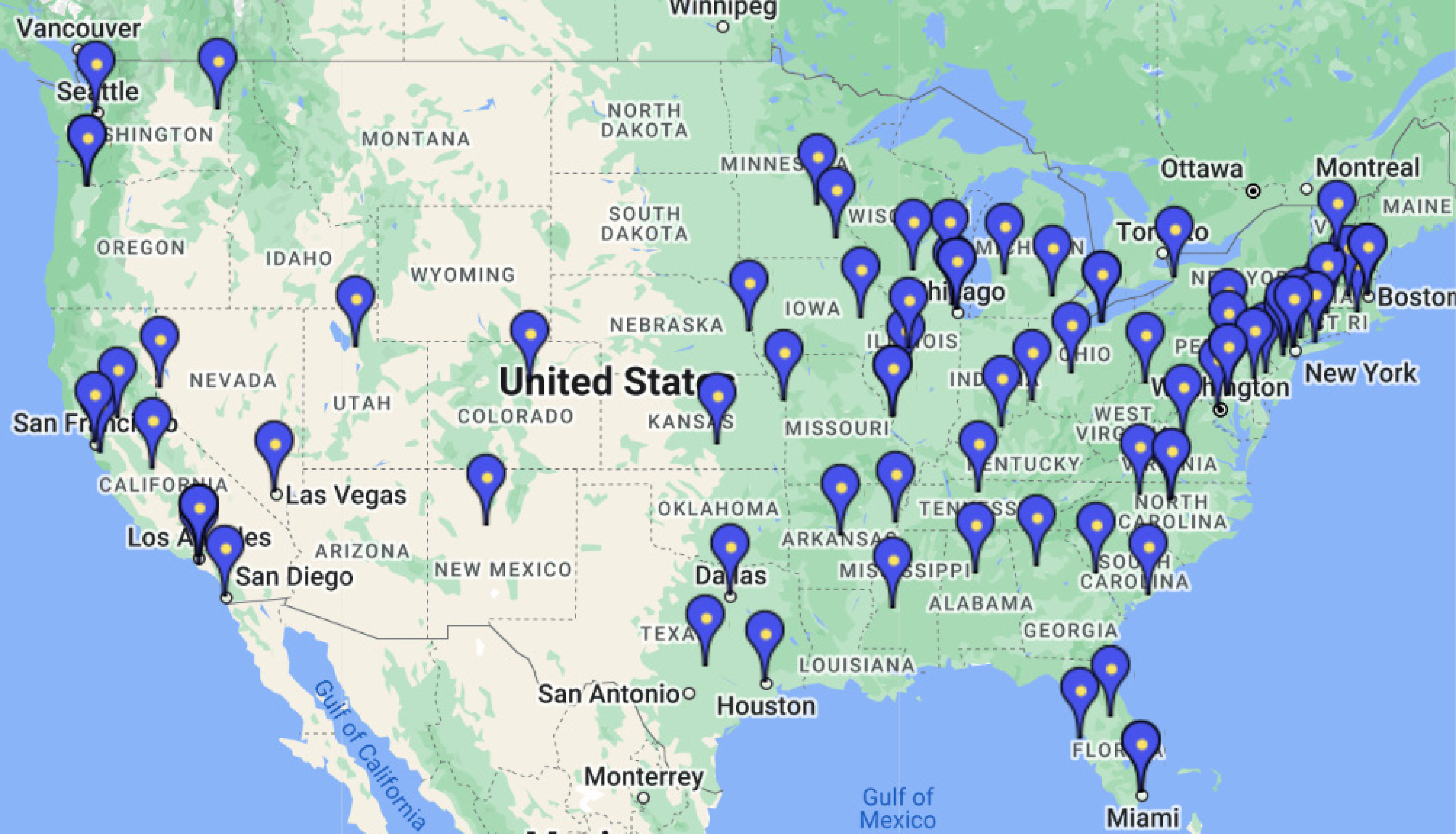

Overall, we received valid responses from 81 unique institutions from 37 states and the District of Columbia, for a 70% overall response rate (Figure 1). The median PICU size was 24 beds (IQR 19-32) and median NICU size was 57 beds (IQR 40-80) (Table 1). Among the respondent institutions, a median of five patients annually transferred from the NICU to the PICU emergently (IQR 2-10), and the most common reasons for emergent transfer from the were extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (32/81, 40%), continuous renal replacement therapy (42/81, 52%), and cardiac surgery (53/81, 65%). Annually, a median of five patients also transferred non-emergently (IQR 3-10) from the NICU to PICU. Only four institutions (5%) reported no non-emergent NICU to PICU transfers.

| n = 81 | Value | |

| Role | Attending | 81 (100) |

| Hospital type | Academic/University-Affiliated | 68 (84) |

| Teaching hospital/non-university | 13 (16) | |

| PICU type | Stand-alone PICU | 54 (67) |

| Mixed PICU/Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Unit | 27 (33) | |

| ACGME fellowship program | PICU | 56 (69) |

| NICU | 68 (84) | |

| Unit size (beds) | PICU, median (IQR) | 24 (19, 32) |

| NICU, median (IQR) | 57 (40, 80) | |

| Non-emergent transfer criteria | Ad hoc (no clinical criteria) | 42 (52) |

| Always initiated by set clinical criteria | 8 (10) | |

| Combination of both | 29 (36) | |

| Other | 2 (2) | |

| Clinical criteria used in non-emergent transfer (n = 37) | Postnatal or corrected age | 29 (78) |

| Size (weight) of patient | 11 (29) | |

| Specific medical diagnoses | 19 (51) | |

| Need for specific medication | 3 (9) | |

| Other | 9 (24) | |

| Protocol to facilitate non-emergent transfer | No | 49 (61) |

| Yes | 27 (33) | |

| Unsure | 5 (6) | |

| Components of transfer process | Bedside nurse handoff | 72 (89) |

| Charge nurse handoff | 39 (48) | |

| Frontline clinician handoff | 60 (74) | |

| Attending to Attending handoff | 70 (86) | |

| Other handoff1 | 4 (5) | |

| Pre-transfer multidisciplinary care team meetings | 34 (42) | |

| Post-transfer bedside huddle | 10 (13) | |

| Post-transfer multidisciplinary care team meetings | 16 (20) | |

| Pre- and/or post-transfer checklists | 4 (5) | |

| Other component2 | 11 (14) | |

| None | 4 (5) | |

Regarding non-emergent transfers, over half (42/81, 52%) of respondents indicated their center transfers patients strictly ad hoc, while only a small minority use clinical criteria all the time (8/81, 10%). Among those who used clinical criteria at least some of the time (37/81, 46%), the most frequently cited clinical trigger was postnatal age or corrected age (29/37, 78%) (Table 1). The age to initiate transfer was variable, ranging from as young as 32 weeks corrected gestational age to 2 years old, with the most common age described as between 4-6 months postnatal age (n = 10). Medical diagnoses frequently triggering non-emergent transfer included bronchopulmonary dysplasia and/or tracheostomy dependence (n = 10) and critical cardiac disease (n = 7).

One-third of respondents (27/81, 33%) indicated that their hospital has a standardized protocol to regularly facilitate non-emergent transfer (Table 1). The most common practice employed outside of bedside nursing and clinician handoff was pre-transfer multidisciplinary meetings (n = 34, 42%), most of which included parents (n = 21). Fewer centers utilize post-transfer multidisciplinary meetings (n = 16), with a small number utilizing checklists (n = 4) or post-transfer bedside huddles (n = 10).

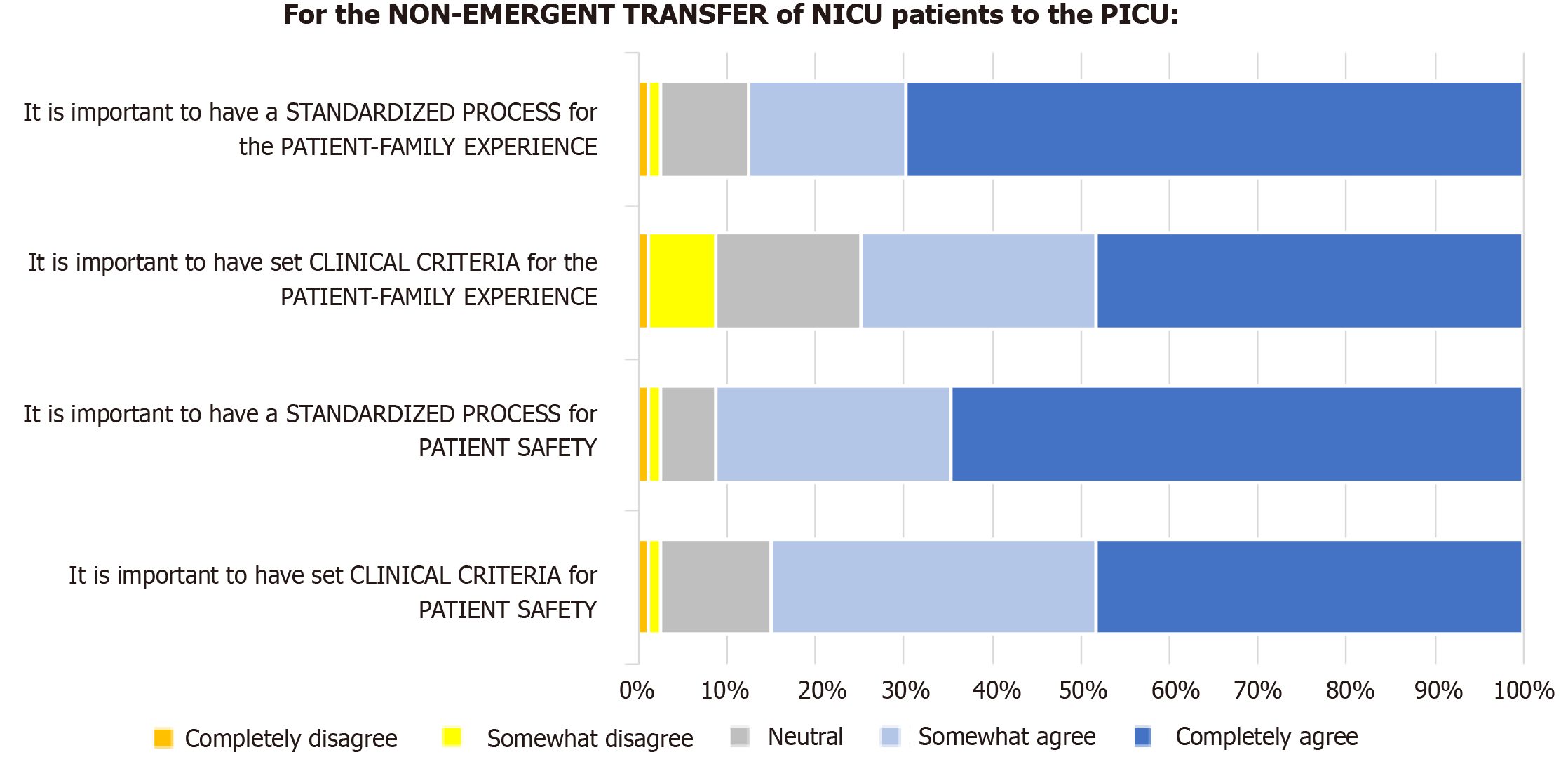

Just under half of respondents evaluated their current institution’s non-emergent NICU to PICU transfer practices as effective for clinicians (37/78, 47%) or patient families (30/78, 38%). Notably, a large minority of respondents were neutral regarding effectiveness for clinicians (26/78, 33%) and patient families (32/78, 41%). Table 2 depicts some common issues arising from respondents’ free text comments regarding these transfer processes, including the importance of expectation setting with families and taking a multidisciplinary approach to transfer. There was broad consensus among physicians that formalizing the transfer process has benefits. Respondents overwhelmingly agreed that having set clinical criteria (59/79, 75%) and standardized protocols (69/79, 87%) for non-emergent transfer were important to the patient-family experience. Similar consensus was found regarding having set clinical criteria (67/79, 85%) and standardized protocols (72/79, 91%) to benefit patient safety (Figure 2).

| Preparing for transfer | |

| Hospital vs patient needs | "[We need to] continue to improve the process of optimizing the transfer time for the Patient rather than for hospital census, etc. I preach the above statements to both the NICU and PICU in my institution frequently” |

| "Having one, or multiple, chronic patients transferred to the PICU from the NICU will impact bed availability significantly more in the PICU than if these patients remain in the NICU. Having the PICU team consult might be a better solution if there are management questions by the NICU team" | |

| "[Our institutional] protocol is not always followed, and transfers always seem to occur at night or on weekends" | |

| Expectation setting | "Parents are communicated about the need of transfer weeks before the actual transfer so they can start thinking about questions they want to bring up to the table prior to the transfer" |

| "Parents get a lot of notice, opportunities to see the PICU, opportunities to meet the PICU clinicians and nursing, so that helps to make the transition smooth" | |

| "Having families visit and meet team members in the PICU is important. Sometimes, this involves multiple meetings. In addition, the goals of care need to be clearly defined. A few patients have significant medical conditions with poor prognosis and their chances are not improved by being transferred to another unit. Families need to understand this reality" | |

| Transfer process | |

| Benefits of multidisciplinary approach | "When able, having the multidisciplinary (primary and consulting physician teams) and interprofessional (MD, RN, RT, PT/OT/speech, CLS, chaplain, etc.) teams meet in advance to discuss the patient's course, status, and goals is beneficial" |

| "Group discussion about the appropriateness of transfer including social work and nursing helps" | |

| Care overlap | "The neonatologists remain easily available if we have questions about care or communicating to parents [in the PICU]" |

| "We have a dedicated PICU attending who rounds every two weeks in the NICU on patients who are older and may need to be transferred. That physician facilitates the transfer and already has a working relationship with the family. A few days before the transfer nursing leadership and child life goes to the NICU and meets the family and the baby" | |

| Post-Transfer adjustment | |

| Medical care differences | "Preparing them [parents] for unit differences, new faces, how quickly PICU titrates/changes things vs NICU pace is needed" |

| "Despite pre-transfer sign out and meetings, the new PICU team has a heightened sense of alertness and attention for at least a few weeks after transfer as we get to know the child. This might translate as repeating work ups that have previously been done, doing more lab draws, more ventilator adjustments, etc. I think this creates questions for parents about whether the PICU does too much or the NICU did too little" | |

| Unit culture differences | "There is a difference in patient care workflow in the NICU and the PICU. This is not well explained to the families and creates 'culture shock' when the patients move" |

| “We do a poor job preparing the parents for the physical change in space. Our NICU is very quiet with specialized sound panels, cozy rooms, dedicated/primary nursing. The PICU is LOUD and BRIGHT, has big sterile feeling rooms, and our unit does not practice primary nursing” | |

Respondents from centers without set clinical criteria to initiate transfer evaluated their centers’ transfers as less effective (36%) than those with some set transfer criteria (59%; P = 0.027). Similarly, those from centers without set transfer protocols evaluated their centers’ transfers as less effective (35%) than those with set protocols (70%; P = 0.007). Meanwhile, respondents evaluated current practices as more effective for parents when their centers had a set protocol in place (63% vs 25%; P = 0.005), but there was no difference in perceived effectiveness for parents in the presence (43%) or absence (33%) of set clinical criteria (P = 0.14). Logistic regression did not indicate that any specific components of the transfer process, NICU or PICU unit size, fellowship program presence, or yearly number of non-emergent transfers were associated with higher effectiveness ratings.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize NICU to PICU transfer practices in the United States. Our cohort was comprised of PICU physicians from academic hospitals with a wide spectrum of PICU sizes and configurations. There was a wide range in the number of non-emergent NICU to PICU transfers completed annually, and only four institutions did not facilitate these transfers at all. Our results show the variability of clinical criteria and transfer protocols used nationwide, with most institutions lacking any criteria or protocol. This data is largely consistent with a survey of NICU medical directors in New Zealand and Australia regarding transfer practices of NICU patients to the PICU, where standardization was rare[13]. The large percentage of respondents endorsing that set clinical criteria and transfer processes would benefit patient safety and the patient-family experience suggests that among PICU physicians, standardization would be welcomed.

Our study has several limitations. Our cohort overrepresents academic centers nationally, though these are the hospitals most likely faced with older, medically complex NICU patients and thus an appropriate focus for this study. While there is consensus from the physicians surveyed that formalization of the transfer process is important for the patient-family experience, a major limitation to this study is the lack of insight from families, which will be central to comprehensive understanding and intervention in this work. Furthermore, our results reflect the knowledge and opinions of only physicians in PICUs across the country; corroboration of these findings among a cohort of neonatologists is important to enriching this data and developing best practices and is now underway. While we were able to achieve a 70% response rate from the hospitals sampled, our results are still subject to selection bias given that 30% of potential respondents did not participate. Additionally, responses for each hospital relied on subjective reports from respondents, which therefore may not accurately represent hospital practice. Going forward, patient outcomes including length of stay, excess morbidity, and mortality are important to understanding this cohort and remains fertile ground for future study. We acknowledge that the ideal transfer process for each individual hospital may vary based on institutional factors beyond the scope of this study, and further research should explore barriers to and facilitators of standardization of these practices. Importantly, our results consistently signal the potential benefits of standardization while aggregating the existing practices used nationally.

Given fewer than half of respondents evaluated their current practices to be effective presently, broad opportunity exists to improve these processes. Ultimately, this study serves as a first step to developing best practices in NICU to PICU transfer for the benefit of a growing population of long-stay patients, their families, and their medical teams. Our findings that the establishment of hospital-specific clinical criteria and protocols are positively associated with favorable evaluations of transfer effectiveness suggest that institutional attention to these activities is beneficial.

This is the first known study of United States institutions regarding non-emergent NICU to PICU transfer practices. We found that most institutions do not have standard practices despite these transfers occurring in the vast majority of respondent institutions. The practices that do exist vary widely with regards to clinical criteria used and steps involved in transfer. Among PICU physician respondents, there was widespread agreement that standardization is important to patient safety and the patient-family experience, and those with existing standard practices rated their NICU to PICU transfers as more effective. While involving other stakeholders will be critical to establishing best practices, these results suggest that standardization of these transfers has benefit.

| 1. | Catlin A. Extremely long hospitalizations of newborns in the United States: data, descriptions, dilemmas. J Perinatol. 2006;26:742-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Sánchez PJ, Van Meurs KP, Wyckoff M, Das A, Hale EC, Ball MB, Newman NS, Schibler K, Poindexter BB, Kennedy KA, Cotten CM, Watterberg KL, D'Angio CT, DeMauro SB, Truog WE, Devaskar U, Higgins RD; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1039-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1793] [Cited by in RCA: 1981] [Article Influence: 198.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boss RD, Henderson CM, Weiss EM, Falck A, Madrigal V, Shapiro MC, Williams EP, Donohue PK; Pediatric Chronic Critical Illness Collaborative. The Changing Landscape in Pediatric Hospitals: A Multicenter Study of How Pediatric Chronic Critical Illness Impacts NICU Throughput. Am J Perinatol. 2022;39:646-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shapiro MC, Henderson CM, Hutton N, Boss RD. Defining Pediatric Chronic Critical Illness for Clinical Care, Research, and Policy. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7:236-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mazur L, Veten A, Ceneviva G, Pradhan S, Zhu J, Thomas NJ, Krawiec C. Characteristics and Outcomes of Intrahospital Transfers from Neonatal Intensive Care to Pediatric Intensive Care Units. Am J Perinatol. 2024;41:e1613-e1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Williams EE, Lee R, Williams N, Deep A, Subramaniam N, Dwarakanathan B, Dassios T, Greenough A. The impact of transfers from neonatal intensive care to paediatric intensive care. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:630-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Davies D, Hartfield D, Wren T. Children who 'grow up' in hospital: Inpatient stays of six months or longer. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:533-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Borenstein-Levin L, Hochwald O, Ben-Ari J, Dinur G, Littner Y, Eytan D, Kugelman A, Halberthal M. Same baby, different care: variations in practice between neonatologists and pediatric intensivists. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:1669-1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Evans R, Madsen B. Culture Clash: Transitioning from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2005;5:188-193. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shapiro MC, Donohue PK, Kudchadkar SR, Hutton N, Boss RD. Professional Responsibility, Consensus, and Conflict: A Survey of Physician Decisions for the Chronically Critically Ill in Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive Care Units. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:e415-e422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Barzegar R, Martin B, Fleming G, Jatana V, Popat H. Implementation of the 'PicNic' handover huddle: A quality improvement project to improve the transition of infants between paediatric and neonatal intensive care units. J Paediatr Child Health. 2022;58:2016-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bjorklund A, Osterholm E, Somani A. Optimal Complex Patient Transfers: NICU Graduation to PICU-Perspective and Process. Adv Pediatr Neonatol Care. 2023;3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Battin MR, McKinlay CJ. How do neonatal units within the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network manage ex-preterm infants with severe chronic lung disease still requiring major respiratory support at term? J Paediatr Child Health. 2019;55:640-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kudchadkar SR, Nelliot A, Awojoodu R, Vaidya D, Traube C, Walker T, Needham DM; Prevalence of Acute Rehabilitation for Kids in the PICU (PARK-PICU) Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Physical Rehabilitation in Critically Ill Children: A Multicenter Point Prevalence Study in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:634-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ista E, Redivo J, Kananur P, Choong K, Colleti J Jr, Needham DM, Awojoodu R, Kudchadkar SR; International PARK-PICU Investigators. ABCDEF Bundle Practices for Critically Ill Children: An International Survey of 161 PICUs in 18 Countries. Crit Care Med. 2022;50:114-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |