Published online Mar 18, 2025. doi: 10.5410/wjcu.v14.i1.104791

Revised: February 23, 2025

Accepted: March 8, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2025

Processing time: 74 Days and 23.8 Hours

Primary renal synovial sarcoma (PRSS) is extremely rare in clinical practice, and most cases are associated with SYT-SSX gene fusion. The PRSS with specific MDM2 gene amplification has not been reported so far. Therefore, there is no practical experience regarding the clinical, pathological features and diagnosis and treatment plans for patients of this type. This article reports a case of PRSS with specific MDM2 gene amplification.

The patient was preoperatively diagnosed with a malignant tumor of the left kidney (with a high probability of clear cell carcinoma). During the operation, a radical left nephrectomy was performed. The postoperative pathological exa

PRSS with MDM2 gene amplification has a poorer prognosis, a higher degree of malignancy, and a faster progression, and clinicians need to be highly vigilant.

Core Tip: Primary renal synovial sarcoma (PRSS) is rare, mostly with SYT-SSX gene fusion. This paper reports a case of PRSS with specific MDM2 gene amplification. The patient had metastasis soon after surgery and died rapidly, suggesting this type of PRSS has poor prognosis, high malignancy and rapid progression, which requires clinical vigilance.

- Citation: Deng CH, Zhou Y, Chen J, He GF, Fu QS, Li JM, Wang G, Hu XD. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations for primary penal synovial sarcoma with specific MDM2 gene amplification: A case report. World J Clin Urol 2025; 14(1): 104791

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v14/i1/104791.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v14.i1.104791

Primary renal synovial sarcoma (PRSS) is extremely rare in clinical practice, accounting for less than 1% of all renal malignant tumors. Its onset is insidious, and most patients are already in the advanced stage when diagnosed. Pathological diagnosis is divided into three types: Monophasic type, biphasic fibrous type and poorly differentiated type, with incidences of 75%, 15% and 10% respectively. The average age of onset is 37 years old, and the median age is 36.2 years old. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 1.14:1[1,2]. The most common clinical manifestations include painless gross hematuria, lumbar and abdominal pain, abdominal distension and abdominal masses. Most patients come to the hospital for the first visit with the above symptoms. So far, there have been fewer than 100 PRSS cases reported worldwide, and almost all of them are case reports on SYT-SSX gene fusions. There is a lack of large-sample single-center studies. Moreover, there has been no report on PRSS cases with specific MDM2 gene amplification in the world at present. Therefore, there is no practical experience regarding the clinical, pathological features and diagnosis and treatment plans for patients of this type.

The novelty of this clinical case lies in its unique pathological type and extremely rapid disease progression, which have never been reported in previous literature. Moreover, the diagnostic and therapeutic considerations we proposed do not rely on previous guidelines or suggestions.

A 64-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital on October 2, 2024 due to "A space-occupying lesion in the left renal area has been detected for over one month".

More than a month ago, the patient presented to an outside hospital due to "left lumbar pain". A urinary system ultrasound examination was performed, which indicated "a space-occupying lesion in the left renal area (nature to be determined)". Due to limited medical conditions, the patient was advised to seek specialized treatment at a superior hospital. During the course of the disease, the patient experienced dull pain and discomfort in the left lumbar and abdominal regions, without symptoms such as frequent urination, urgent urination, or hematuria. The patient followed the doctor's advice and visited the outpatient department of the urology department of our hospital. Subsequently, the patient was admitted to the urology department with the diagnosis of "undetermined nature of the left renal mass". Since the onset of the illness, the patient's diet, sleep, and mental state have been normal, with normal bowel and bladder functions, and no significant change in body weight.

The patient had no previous history of special diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, or coronary heart disease, nor any history of surgery or trauma.

The patient has no family history of genetic diseases.

A palpable mass in the left upper abdomen, with unclear boundaries, hard texture, and difficult to move, without obvious tenderness, and mild percussion pain in the left renal area.

Laboratory examinations were regular, without signs of anemia or systemic infection.

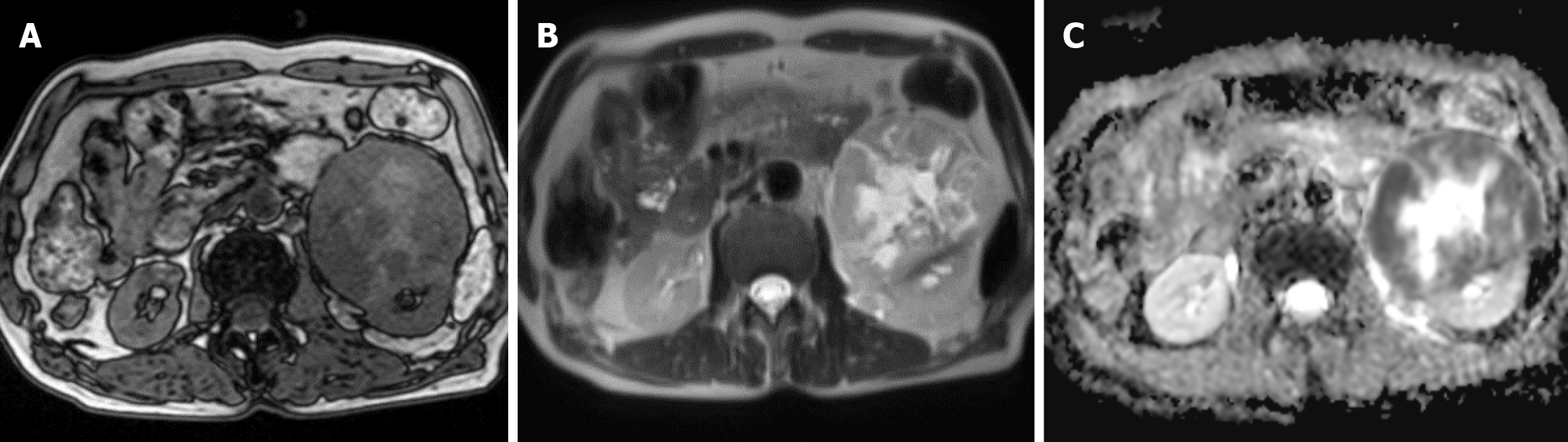

Computed tomography (CT) urography of the urinary collection system showed a slightly low-density heterogeneous mass in the left renal parenchyma. The mass had an unclear boundary with the left psoas major muscle, and calcifications were seen within the lesion. The size was approximately 11.0 cm × 8.9 cm × 8.1 cm. After enhanced scanning, it showed heterogeneous mild-to-moderate enhancement, with an average CT value of 28 Hu and an enhanced CT value of 55 Hu. No enlargement of abdominal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes was observed (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a mass-like iso/long T1 and iso/long T2 signal shadow in the anterior inferior pole of the left kidney. On diffusion-weighted imaging, the lesion showed a high/low heterogeneous signal, and on the apparent diffusion coefficient, it showed a low/high heterogeneous signal. The signal of the lesion was heterogeneous, and the boundary was relatively clear. The size was approximately 8.7 cm × 9.1 cm × 10.7 cm, and the lesion had an unclear boundary with the left renal cortex (Figure 2).

The patient was then transferred to our intensive care unit for close monitoring over the subsequent 24 hours. Throughout this period, the patient's hemodynamic parameters remained remarkably stable. After a thorough consultation with the general surgeons, it was collectively decided that surgical intervention would not be pursued at this stage.

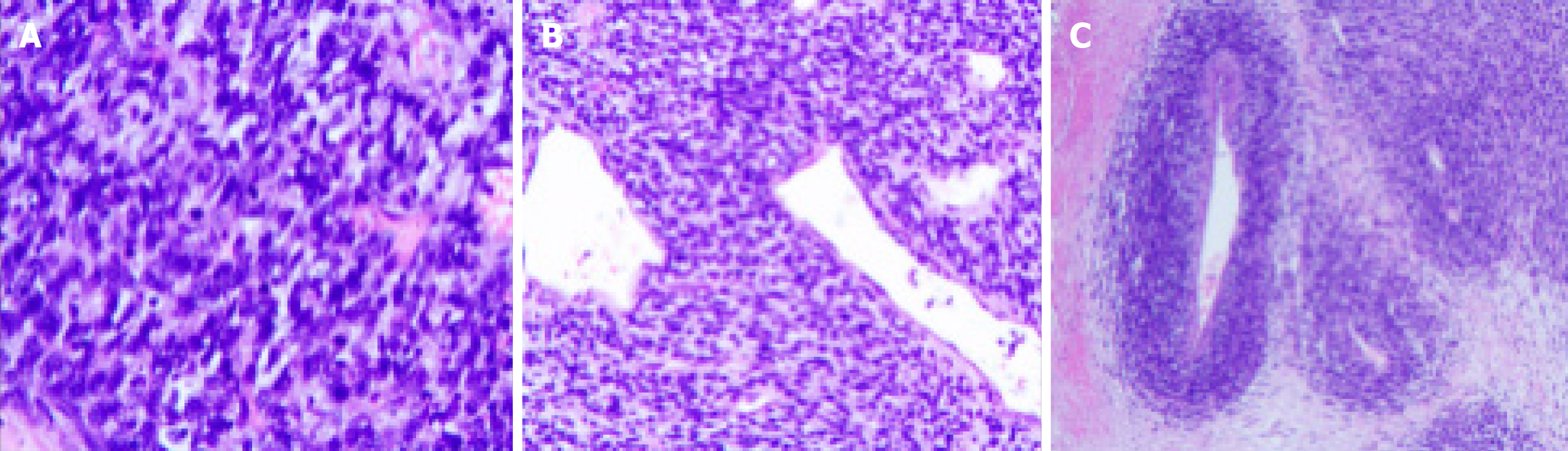

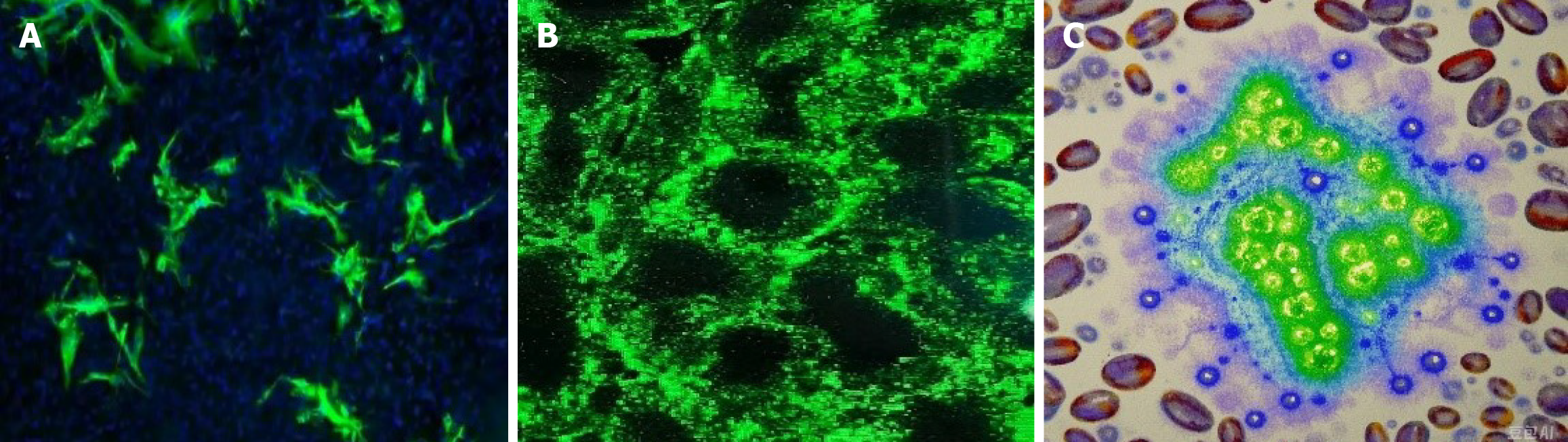

Based on the postoperative pathological examination results and genetic testing results, the patient was finally diagnosed with synovial sarcoma of the left kidney (MDM2 gene amplification type), with negative surgical margins. Postoperative pathology (Figure 3) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure 4): (1) (Left kidney) synovial sarcoma, without invasion of surrounding tissues; and (2) IHC: HMB45 (-), MELAN-A (-), SMA (-), Ki-67 (50% +), P-CK (-), CD34 (-), PAX-8 (-), S-100

Since the patient refused subsequent radiotherapy and chemotherapy, no further treatment was administered after the surgery.

The patient did not return to the hospital for follow up examinations after being discharged. Forty- eight days after the operation, the patient presented with "abdominal distension and diarrhea" and was admitted to the gastroenterology department. After a comprehensive system examination, a huge metastatic tumor (15.1 cm × 11.3 cm × 10.3 cm) was found in the original left renal area. The patient died clinically 17 hours after admission due to "multiple organ failure" despite rescue efforts.

Clinically, the diagnosis and differentiation of PRSS are relatively difficult. Molecular genetic detection of SYT-SSX gene fusion is the gold standard. SYT-SSX gene fusion can be found in more than 90% of PRSS patients, and SYT-SSX2 is the most common type[2]. The SYT-SSX fusion gene is formed by chromosomal translocation between the short arm of chromosome X at region 11 and the long arm of chromosome 18 at region 11. It transactivates through signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin and ERK to promote the proliferation of tumor cells. Although gene detection has failed to find targets for targeted therapy and evidence related to immunity, it has certain reference value in excluding drug-resistant and negatively correlated genes. However, due to limitations in gene sampling, fluorescence in-situ hybridization is still the most commonly used method for diagnosing PRSS in clinical practice. It can be combined with the results of immunohistochemical staining to differentiate from sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma, renal leiomyosarcoma and fibrosarcoma. PRSS usually shows positive expressions of Bcl-2, CD99, CD56, TLE-1 and vimentin, and epithelial membrane antigen shows aggregation, but it does not express Esmin, SMA, S-100, etc. The sensitivity and specificity of TLE-1 positivity in diagnosing this disease are as high as 92% and 81% respectively, and the negative predictive value reaches 96%[3]. In terms of imaging, PRSS mainly relies on CT and MRI for preliminary diagnosis. CT examination shows a cystic-solid mass with uneven density, and enhanced scanning shows uneven enhancement. In typical cases, the solid part shows "fast wash-in and slow wash-out", which can be differentiated from clear cell renal cell carcinoma with "fast wash-in and fast wash-out" and papillary renal cell carcinoma with "progressive enhancement". In MRI examination, T1WI is often iso-intense, and T2WI is unevenly hyperintense. There may be a "triple-ring sign". Some scholars have reported that when MRI finds bleeding, calcification and air-fluid levels in renal masses, attention should be paid to this disease, but there is still a lack of typical imaging features[4]. The results of immunohistochemistry, CT and MRI of this patient are basically consistent with those reported in previous literatures. Therefore, patients with PRSS with MDM2 gene amplification still have no specific immunohistochemical or imaging manifestations, and gene detection is still required for diagnosis.

In retroperitoneal tumors, MDM2 amplification highly suggests the possibility of liposarcoma. Its epidemiological characteristics and CT imaging manifestations are extremely similar to those of synovial sarcoma[5]. The difference lies in that under the microscope, synovial sarcoma with MDM2 amplification shows spindle-shaped tumor cells distributed in sheets or bundles, arranged closely, with scanty cytoplasm, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, and obvious nuclear atypia. In contrast, liposarcoma is composed of relatively mature adipose tissue and a small amount of univacuolated and multivacuolated lipoblasts under the microscope. It is separated by fibrous tissue into adipose lobules of different sizes, and the inconsistent size of adipocytes within the lobules is the main characteristic. In terms of immunohistochemistry, synovial sarcoma with MDM2 amplification is negative for CD34, while liposarcoma is positive for CD34 and CDK4[6]. When the diagnosis is difficult, differentiation can be made through pathological diagnosis, genetic markers.

Radical surgery is the preferred treatment for PRSS. It is recommended regardless of whether there is metastasis at the time of diagnosis[7]. However, the prognosis of PRSS is poor. The recurrence rate reported in the literature is 29.6%-39.8%, and the mortality rate is 22.2%-29.0%[1,2]. There is great controversy regarding the clinical efficacy of post

In conclusion, we believe that PRSS with MDM2 gene amplification has a worse prognosis, a higher degree of malignancy and a faster progression, and high clinical vigilance is required. However, for the treatment of PRSS, radical nephrectomy is necessary. Although the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of PRSS has not been determined, the possible benefits of this adjuvant treatment plan should be informed to the patients.

| 1. | Taniguchi M, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K, Hatano S, Sasaki A, Tsuneyoshi M. Extraskeletal synovial sarcoma: Analysis of 107 cases with evaluation of prognostic factors. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:742-750. |

| 2. | Zhao X, Liu Y, Sun X, Wang X, Yang J, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Wang C, Liu Y. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma: A single - center experience and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:177. |

| 3. | Yang L, Chen S, Luo P, Yan W, Wang C. Liposarcoma: Advances in Cellular and Molecular Genetics Alterations and Corresponding Clinical Treatment. J Cancer. 2020;11:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Conyers R, Young S, Thomas DM. Liposarcoma: molecular genetics and therapeutics. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:483154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Klett DE, Mazzone A, Summers SJ. Endoscopic Management of Iatrogenic Ureteral Injury: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Endourol Case Rep. 2019;5:142-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lim JCE, Cauldwell M, Patel RR, Uebing A, Curry RA, Johnson MR, Gatzoulis MA, Swan L. Management of Marfan Syndrome during pregnancy: A real world experience from a Joint Cardiac Obstetric Service. Int J Cardiol. 2017;243:180-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shindo Y, Unsinger J, Burnham CA, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. Interleukin-7 and anti-programmed cell death 1 antibody have differing effects to reverse sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Shock. 2015;43:334-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gomez-Brouchet A, Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Judson I, Blay JY, Bompas E, Lejeune D, Verhoeven J, Van Glabbeke M, Bonvalot S, Casali PG, Reichardt P, Tienghi X, Miah AB, Tascilar M, Le Prise E, Mir O, Penel N, Schoffski P, Stacchiotti S, van Oosterom AT, Blum MG. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-risk soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities or trunk wall: A randomized phase 2 trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11: 1055-1064. |

| 9. | Baldini EH, Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Antman KH, Benjamin RS, Casper ES, Chawla S, Cooney MM, Eilber FR, Gladdy RA, Goorin AM, Healey JH, Henshaw RM, Lewis JJ, Maki RG, Merchant NB, Mital D, O'Sullivan B, Qin J, Reitherman C, Raut CP, Singer S, Smith MA, Tap WD, Wagner AJ, Wexler LH, Yang JC, Zalupski M, Blum MG. Adjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremity: Updated results of a prospective, randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1120-1126. |

| 10. | Zhai YX, Zhang Y, Fan HT, Li RW, Feng SQ, Zhang XY, Yang XS, Sun HH, Zhang M. [A case report of primary renal synovial sarcoma]. Zhonghua Miniaowaike Zazhi. 2022;43:138-139. [DOI] [Full Text] |