Published online Jun 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i2.100336

Revised: January 26, 2025

Accepted: February 17, 2025

Published online: June 9, 2025

Processing time: 215 Days and 14.3 Hours

Chronic idiopathic uveitis (CIU) and juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (U-JIA) are both vision-threatening conditions that share similar autoimmune mechanisms, but treatment approaches differ significantly. In managing U-JIA, various treatment options are employed, including biological and non-biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. These drugs are effective in clinical trials. Given the lack of established diagnostic and treatment guidelines as well as the limited number of therapeutic options available, patients with CIU frequently do not receive optimal and timely immunosuppression. This study highlighted the necessity for additional research to develop novel diag

To compare the characteristics and outcomes of U-JIA and CIU.

A retrospective cohort study analyzed data from 110 pediatric patients (under 18 years old) with U-JIA and 40 pediatric patients with CIU. Data was collected between 2012 and 2023. The study focused on demographic, clinical, treatment, and outcome variables.

The median onset age of arthritis was 6.4 years (2.7 years; 9.3 years). In 28.2% of cases uveitis preceded the onset of arthritis. In 17.3% of cases it occurred simultaneously. In 53.6% of cases it followed arthritis. Both groups had similar onset ages, antinuclear antibodies/human leukocyte antigen positivity rates, and ESR levels, with a slight predominance of females (60.9% vs 42.5%, P = 0.062), and higher C-reactive protein levels in the U-JIA group. Anterior uveitis was more prevalent in patients with U-JIA (P = 0.023), although the frequency of symptomatic, unilateral, and complicated forms did not differ significantly. The use of methotrexate (83.8% vs 96.4%) and biologics (64.7% vs 82.1%) was comparable, as was the rate of remission on methotrexate treatment (70.9% vs 56.5%) and biological therapy (77.8% vs 95%), but a immunosuppressive treatment delay in CIU observed. Patients with CIU were less likely to receive methotrexate [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.48, P = 0.005] or biological treatment (HR = 0.42, P = 0.004), but they were more likely to achieve remission with methotrexate (HR = 3.70, P = 0.001).

Treatment of uveitis is often limited to topical measures, which can delay systemic therapy and affect the outcome. Methotrexate and biological agents effectively manage eye inflammation. It is essential to develop standardized protocols for the diagnosis and management of uveitis, and collaboration between rheumatologists and ophthalmologists is needed to achieve optimal outcomes in the treatment of CIU.

Core Tip: It has been observed that the human leukocyte antigen-B27 allele behaves differently depending on the age of the individual. In individuals with human leukocyte antigen-B27 positivity over the age of seven, there is a significantly increased likelihood of developing acute uveitis compared to those under the age of seven. Despite this, systemic therapy appears to be equally effective in both groups albeit with delayed administration in children with chronic idiopathic uveitis.

- Citation: Yakovlev AA, Gaidar EV, Sorokina LS, Nikitina TN, Kalashnikova OV, Kostik MM. Uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and chronic idiopathic uveitis in children: A retrospective cohort study. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(2): 100336

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i2/100336.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i2.100336

Uveitis is a broad term that encompasses over 30 distinct clinical conditions characterized by inflammation affecting various parts of the eye[1]. It typically refers to localized inflammation within the uvea, which is located between the retina and the outermost layers of the eye, including the sclera and cornea. The uveal tract includes the iris, ciliary body, and proper choroid[2,3]. Due to their proximity, uveitis is frequently regarded not only as inflammation of the mid-portion of the eye but also as inflammation affecting adjacent structures such as the retina, optic nerve, vitreous body, and sclera[4].

Most cases of pediatric uveitis are non-infectious in nature and are associated with conditions such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), juvenile spondyloarthropathies, tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis-syndrome, sarcoidosis, Blau’s syndrome, and Behçet’s disease[5]. Chronic idiopathic uveitis (CIU) and JIA-associated uveitis (U-JIA) are vision-threatening disorders with similar mechanisms. While U-JIA offers multiple treatment options, including biological and non-biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), CIU is a clinical challenge due to the lack of specific treatments available[6].

Pediatric uveitis is much less common than in adults, accounting for only around 5%-10% of all uveitis cases in the general population[4]. Recent data suggested that the number of uveitis cases has risen in recent years. For instance, a study conducted in Finland[6] examined 150 children under the age of 16 who were diagnosed with uveitis between 2008 and 2017. The study found that the prevalence of uveitis increased from 64 cases per 100000 children in 2008 [n = 51; 95% confidence interval (CI): 47.7-84.2] to 106 cases per 100000 in 2017 (n = 48; 95%CI: 88.0-158.3). During this period, the average incidence was 14 cases per 100000 people, with no significant difference between males and females[7,8]. Similarly, a Korean national study reported the incidence of non-infectious uveitis in children to be 4.64 per 100000 person-years and 8.25 per 100000 person-years, respectively[9].

The treatment of uveitis typically involves a step-by-step approach, gradually increasing the intensity of therapy. Initially, topical glucocorticoid medication is used, followed by systemic glucocorticoid administration in cases of severe uveitis with the potential for significant vision loss. If the initial treatment is ineffective or corticosteroid dependence develops, immune suppression therapy may be initiated. Methotrexate is the primary immunosuppressive drug used for uveitis treatment. Other immunosuppressive agents include mycophenolate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine. Biological therapies such as infliximab, adalimumab, tocilizumab, and abatacept are also used. Rituximab is an additional treatment option[10].

In the prebiological era, uveitis had extremely serious outcomes. Seven years after the onset of the condition, 42% of patients developed cataracts, and 5% developed glaucoma. By age 24, 51% had cataracts, 22% had glaucoma, and 49% showed signs of active uveitis that required topical glucocorticoid treatment for exacerbations. Uveitis into adulthood can become asymptomatic, but nearly half of the patients with JIA showed disease activity even after this period[11,12].

Both conditions are caused by immune processes involving CD4+ T cells and the interaction of genetic and environmental factors, although the exact triggers for uveal inflammation are unclear. Individual risk factors such as sex and age play a significant role in developing uveitis both in idiopathic cases and in those associated with JIA[6,7,13].

Based on the assumption that autoimmune chronic uveitis has a common pathogenesis, including uveitis associated with JIA, the aim of this study was to conduct a comparative analysis between these two diseases.

The observational retrospective cohort study analyzed medical records of patients aged under 18 years who were diagnosed with uveitis and JIA and treated at pediatric rheumatology or ophthalmology clinics in Saint Petersburg between September 2012 and May 2023.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosis of uveitis either as U-JIA or CIU; and (2) Age under 18 years.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosed with systemic diseases other than JIA, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, systemic connective tissue disorders, and autoimmune inflammatory conditions; (2) Uveitis caused by infection or other etiologies; and (3) Masquerade syndromes.

The diagnosis of JIA was established according to International League of Associations for Rheumatology criteria[14].

Eye involvement was assessed through a comprehensive ophthalmological examination, including biomicroscopy, by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature classification[3]. All patients underwent fundus examination with pharmacological mydriasis. In cases where the posterior pole of the eye could not be visualized, a Goldman lens was used to aid in the examination. If any type or degree of uveitis was detected or the diagnosis was uncertain, patients underwent additional imaging studies, including ultrasound examination of the eyes and optical coherence tomography of the posterior segment. Additionally, all patients with suspected uveitis were subjected to tonometry to exclude potential complications.

We applied the remission criteria based on the guidelines of the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature working group. Remission was defined as the complete absence of inflammatory cells (grade 0) in the anterior chamber and/or vitreous for a specified period, without the need for increased therapy[3].

Each patient underwent a comprehensive examination by a rheumatologist to confirm the diagnosis of JIA and determine the specific subtype of JIA. Additionally, an ophthalmological assessment was performed. The medical records of each patient were independently reviewed by two experienced pediatric rheumatologists (Yakovlev AA and Sorokina LS). In cases where there was a discrepancy in the determination of the JIA subtype, the records were reviewed by a third independent expert rheumatologist (Kostik MM), who provided a final opinion on the patient’s JIA subtype. Only matched cases were included in the study.

From the medical records, the following information was extracted: (1) Demographic information including sex, JIA subtype, age at JIA onset, and number of active joints at JIA onset; (2) Uveitis characteristics including age at onset of uveitis, anatomical type of uveitis at onset and last visit, laterality of eye involvement at onset and latest visit, type of uveitis presentation (acute or asymptomatic), presence of U-JIA before, concurrent with, or following joint involvement. Individuals for whom it was challenging to determine the onset of uveitis or those without an apparent “red eye” were classified as having an asymptomatic onset. Data about the achievement of remission, flares, a time before these events, the presence of uveitis-associated complications, and surgery were also collected; (3) Presence of complications during the initial examination, including the type of complication (when no information on complications was available, the individual was classified as having none), history of ophthalmic surgery, and date of surgery; (4) Laboratory characteristics including the presence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 and antinuclear antibodies (ANA); ESR, and C-reactive protein (CRP) at onset; and (5) Treatment with conventional and biologic DMARDs and time for their prescription.

The analysis was conducted in the following subgroups: (1) Males and females; (2) ANA-positive and ANA-negative; (3) Associated with HLA-B27 and without HLA-B27; (4) Unilateral and bilateral; and (5) Children with HLA-B27 before age 7 years and at age 7 years and older.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the R programming language version 4.4.0, dated April 24, 2024, in the RStudio environment version 2024.04.2, build 764. Categorical data were presented in absolute terms. Independent categorical variables were compared using 2 × 2 contingency tables and Fisher’s exact tests. Quantitative variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and were presented as the mean, median, first and third quartiles (25%, 75%), minimum, and maximum values. If the data conformed to a normal distribution, a paired t-test was used to compare two independent quantitative variables. Otherwise, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. Survival analysis was conducted for each group using the Kaplan–Meier method, with treatment outcomes (methotrexate treatment and biological therapy, remission achievement) as events of interest. The log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Factors significantly associated with uveitis outcome times were then tested using a Cox proportional hazards regression model to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95%CI. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Additionally, logistic and mixed regression models were employed to assess the impact of predictors.

The study included 150 participants, all of whom had 232 eyes affected by uveitis. Of these, 84 participants (56%) were female, and 66 participants (44%) were male. The mean age of the participants at the time of uveitis diagnosis was 7.2 years, with a median of 6.3 years (range 4.4 years to 9.1 years). Participants were divided into two groups: (1) U-JIA (n = 110); and (2) CIU (n = 40).

Initial treatment with methotrexate monotherapy was recorded for 131/150 patients (87.3%), and 74/131 patients (56.5%) achieved remission. However, 41/131 participants (31.3%) did not achieve remission, and information was missing for 16/131 individuals (12.2%). Seven patients (4.7%) received monotherapy with adalimumab, and 106/150 participants (70.7%) received combined therapy with non-biological and biological DMARDs, including (1) Abatacept: 1 (0.9%); (2) Adalimumab: 95 (89.6%); (3) Golimumab: 3 (2.8%); (4) Infliximab: 6 (5.8%); and (5) Tocilizumab: 1 (0.9%). Of these, 79/106 patients (74.5%) achieved remission, while 7/106 participants (6.6%) did not achieve remission. Information about remission status was missing for 20/106 participants (18.9%).

The JIA group consisted of 43 males (39.1%) and 67 females (60.9%). The most common types of JIA were oligoarthritis (n = 61, 55.5%), enthesitis-related arthritis (n = 22, 20.0%), undifferentiated arthritis (n = 22, 22.0%), polyarthritis (n = 3, 2.7%), and psoriatic arthritis (n = 2, 1.8%). The mean age of arthritis onset was 6.4 years, with a median age of 5.6 years (range: 2.7–9.3 years; minimum: 1.0 year; maximum: 16.2 years). The mean age of uveitis onset in this group was 7.2 years, and the median age was 6.4 years (range: 4.4–9.0 years). Forty patients (36.4%) presented with “red eye” symptoms at the time of onset. Eye complications were detected at the initial examination in 34 patients (30.9%). At onset, 49 patients (44.5%) had unilateral ocular involvement. Based on the anatomical distribution, anterior uveitis was diagnosed in 81 patients (73.7%), pars planitis in 4 patients (3.6%), posterior uveitis in 4, and panuveitis in 21.

HLA-B27 was present in 18/51 patients (35.3%), and 60 out of 104 patients (57.7%) tested positive for ANA. The mean CRP level was 24.3 mg/L, with a median value of 1.5 mg/L [interquartile range (IQR): 1.0 mg/L, 17.0 mg/L], and a minimum of 0 and maximum of 192. The average ESR was 28 mm/hour, with a median of 22 mm/hour (IQR: 15, 47), and a minimum of 2 mm/hour and maximum of 78 mm/hour.

Methotrexate monotherapy was given to 95/110 study participants (86.4%), and 57 of those patients (60.0%) achieved remission. A total of 28 participants (29.5%) did not achieve remission, and information was missing for 10 participants (10.5%). Uveitis relapsed in 26/57 patients (45.6%), 24 patients (42.1%) remained in remission, and there was no information available for 7 patients (12.3%).

Seven of the 110 patients (6.4%) received biological monotherapy using adalimumab, with 6 patients achieving remission (85.7%). Combined treatment with a non-biological DMARD and a biological DMARD was prescribed for 77/110 patients: (1) 67 received adalimumab (87.0%); (2) 5 received infliximab (6.5%); (3) 2 received golimumab (2.6%); and (4) one each received abatacept or tocilizumab.

Remission was achieved among 54/77 patients (70.1%), while 6 patients did not achieve it. Information was missing for 17 patients (22.1%). Recurrent uveitis occurred among 22/54 patients who had previously achieved remission (40.7%), while 23 did not have a relapse, and 9 patients had missing information.

In the cohort of patients with CIU, there were 23 males (57.5%) and 17 females (42.5%). The mean age at onset was 7.1 years (5.2; 9.4) with a median of 6.2 years and a minimum and maximum age of 1 year and 15 years, respectively. Based on the anatomical classification, 20 patients (50.0%) had anterior uveitis, 4 patients (10.0%) had posterior uveitis, and 14 patients (35%) had panuveitis. A “red eye” symptom had 17 individuals (42.5%), while unilateral involvement at onset was noted in 18 patients (46.2%). At the initial examination, complications were identified in 12 cases (30.0%). HLA-B27 testing was performed in 21 patients, with 5 (23.8%) testing positive, and ANA testing was positive in 20/35 participants (57.1%). The mean CRP level was 8.8 mg/L with a median of 0.98 mg/L (0.34 mg/L, 1.7 mg/L), and the minimum and maximum levels were 0.07 mg/L and 60 mg/L, respectively. ESR values averaged 10 mm/hour (8 mm/hour, 21 mm/hour).

Methotrexate was administered as monotherapy to 36/40 patients (90.0%), and remission was achieved in 17 (47.2%). A total of 13 patients (36.1%) did not achieve remission, and data for 6 patients (16.7%) was not available. Relapse of uveitis occurred in 13/17 patients (76.5%) treated with the medication. Three patients (17.6%) did not relapse, and data was unavailable for 1 patient (5.9%).

Combined therapy with non-biological and biological DMARDs was administered to 30 patients (75.0%), including 28 treated with adalimumab, 1 with infliximab, and 1 with golimumab. Treatment outcome data were available for 26 of them, among whom 25 patients (96.2%) achieved remission, while only one did not achieve remission. Relapse of uveitis was observed in 11 patients (44.0%) who achieved remission, with 11 having a non-recurrent course. Data was unavailable for 3 patients.

The main differences between the two study groups were a trend towards a predominance of females (P = 0.062), a higher prevalence of anterior uveitis (P = 0.023), and higher levels of CRP (P = 0.035) among patients with U-JIA compared with those with CIU. A full description of the data is in Table 1.

| Parameter | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (n = 110) | Chronic idiopathic uveitis (n = 40) | P value |

| Females | 67 (60.9) | 17 (42.5) | 0.062 |

| Age at diagnosis of uveitis (years) | 0.648 | ||

| Mean | 7.2 | 7.1 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 6.4 (4.4, 9.0) | 6.2 (5.2, 9.4) | |

| Min–max | 1.8-17.7 | 1.0-15.0 | |

| Age at diagnosis of arthritis (years) | |||

| Mean | 6.4 | - | - |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 5.6 (2.7, 9.3) | ||

| Min–max | 1.0-16.2 | ||

| Anatomical type of uveitis | 0.023 | ||

| Anterior | 81 (73.6) | 20 (50.0) | |

| Pars planitis | 4 (3.6) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Posterior | 4 (3.6) | 4 (10.0) | |

| Panuveitis | 21 (19.2) | 14 (35.0) | |

| Manifested (“red-eye”) uveitis | 40 (36.4) | 17 (42.5) | 0.569 |

| Unilateral uveitis | 49 (44.5) | 18/39 (46.2) | 1.0 |

| Eye complications at first examination | 34 (30.9) | 12 (30.0) | 1.0 |

| Antinuclear antibodies positivity | 60/104 (57.7) | 20/35 (57.1) | 1.0 |

| Human leukocyte antigen-B27-positivity | 18/51 (35.3) | 5/21 (23.8) | 0.413 |

| Uveitis appearance | - | - | |

| Before arthritis | 31 (28.2) | ||

| Simultaneously with arthritis | 19 (17.3) | ||

| After arthritis | 59 (53.6) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.035 | ||

| Mean | 24.3 | 8.8 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.50 (1.00, 17.00) | 0.98 (0.34, 1.70) | |

| Min-max | 0-192.00 | 0.07-60.00 | |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 28.0 | 18.0 | 0.179 |

| Mean | 22.0 (15.0, 47.0) | 10.0 (8.0, 21.0) | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 2.0-78.0 | 4.0-60.0 | |

| Min-max | |||

| Active joint at onset | - | - | |

| Mean | 2.0 | ||

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | ||

| Min-max | 1.0-7.0 |

Of the 150 patients, 96 who had complete follow-up data for at least one year were selected. There were 28 patients (29.2%) with CIU, and 68 patients (70.8%) with U-JIA. Patients with CIU experienced a longer delay in starting methotrexate therapy compared with patients with U-JIA, and remission rates were identical between the two groups. Interestingly, patients with CIU showed a higher incidence of flares of the disease [odds ratio (OR) = 12.4, 95%CI: 1.60-566.10, P = 0.004] with a similar time interval between flares. The time from starting methotrexate to starting biologics was comparable, although the time from disease onset was longer due to the delayed start of methotrexate. The remaining treatment outcomes were comparable in the two study groups. The main results of the treatment are summarized in Table 2.

| Parameter | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (n = 68) | Chronic idiopathic uveitis (n = 28) | P value |

| Received MTX | 57 (83.8) | 27 (96.4) | 0.171 |

| Time to MTX prescription (years) | 0.004 | ||

| Mean | 1.1 | 2.6 | |

| median (25%, 75%) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.5) | 0.8 (0.3, 7.2) | |

| Min–max | 0.0–8.4 | 0.0–11.4 | |

| Remission on MTX | 39/55 (70.9) | 13/23 (56.5) | 0.293 |

| Time to remission on MTX (years) | 0.002 | ||

| Mean | 1.10 | 0.19 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 0.30 (0.30, 0.60) | 0.17 (0.08, 0.17) | |

| Min–max | 0.04–8.20 | 0.08–0.80 | |

| Flare on MTX | 25/54 (46.3) | 11/12 (91.7) | 0.004 |

| Time to first flare on MTX (years) | 0.402 | ||

| Mean | 0.90 | 1.30 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 0.60 (0.30, 1.10) | 1.10 (0.30, 1.50) | |

| Min–max | 0.10–4.30 | 0.17–3.30 | |

| Biological treatment | 44 (64.7) | 23 (82.1) | 0.141 |

| Time since MTX to biologics (years) | 0.593 | ||

| Mean | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.0 (0.4, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.5, 3.0) | |

| Min–max | 0.3–4.8 | 0.2–7.0 | |

| Time before biological treatment (years) | 0.020 | ||

| Mean | 2.3 | 4.4 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.6 (0.6, 3.7) | 3.2 (1.4, 7.2) | |

| Min–max | 0.0–8.0 | 0.3–12.5 | |

| Remission on biological treatment | 35/45 (77.8) | 19/20 (95.0) | 0.151 |

| Time to remission on biological treatment (years) | 0.980 | ||

| Mean | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 0.20 (0.10, 0.40) | 0.20 (0.10, 0.40) | |

| Min–max | 0.00–1.00 | 0.01–1.00 | |

| Flare on biological treatment | 18/34 (52.9) | 11/19 (57.9) | 0.780 |

| Time to first flare on biological treatment (years) | 0.233 | ||

| Mean | 1.9 | 1.2 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.6 (0.8, 2.5) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.9) | |

| Min–max | 0.1–5.1 | 0.1–3.6 | |

| Received intraocular corticosteroid injections | 32 (47.1) | 18 (64.3) | 0.177 |

| Undergone surgery | 18 (26.5) | 7 (25.0) | 1.0 |

| Time to eye surgery (years) | 0.796 | ||

| Mean | 4.5 | 5.0 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 3.9 (1.3, 6.5) | 4.5 (2.5, 5.2) | |

| Min–max | 0.1–10.7 | 1.3–12.5 |

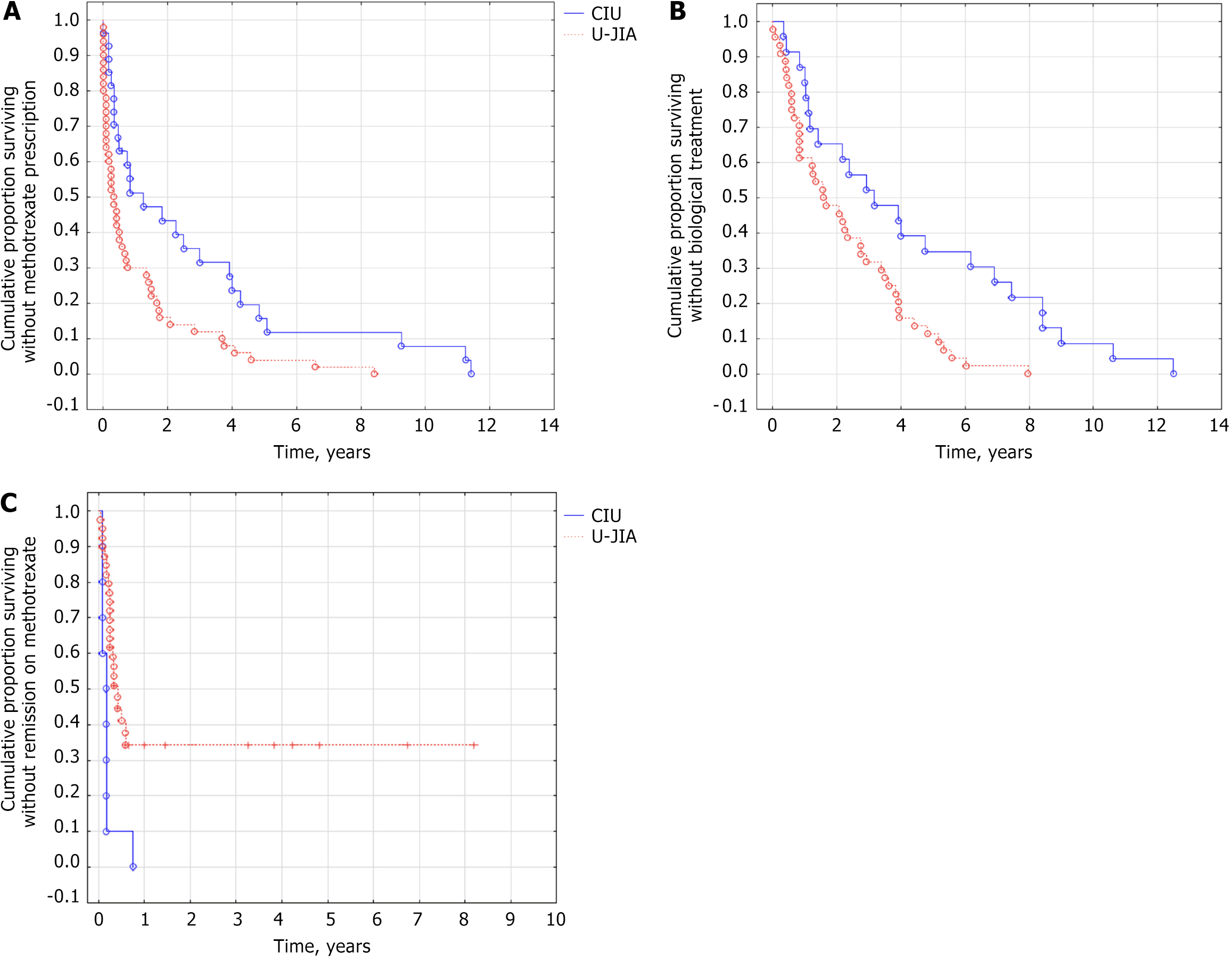

Patients with CIU had a significantly lower cumulative probability of receiving methotrexate therapy (log rank test P = 0.002, HR=0.48 (95% CI: 0.29; 0.83, P = 0.005) (Figure 1A) and biological therapy (log rank test P = 0.003, HR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.24-0.77, P = 0.004) (Figure 1B) compared to U-JIA. However, patients with CIU were more likely to achieve remission of uveitis during methotrexate treatment (log rank test P = 0.004, HR = 3.7, 95%CI: 1.70-8.30, P = 0.001) (Figure 1C).

In the entire uveitis cohort (U-JIA and CIU), HLA-B27 testing revealed a tendency towards male predominance in the presence of HLA-B27 (P = 0.071). Additionally, the presence of HLA-B27 was associated with an increased prevalence of manifested (“red eye”) uveitis (OR = 5.1, 95%CI: 1.60-17.50, P = 0.004) as well as unilateral involvement (OR = 5.2, 95%CI: 1.60-19.30, P = 0.002). These findings are presented in Table 3.

| Parameter | HLA-B27 (+) (n = 23) | HLA-B27 (-) (n = 49) | P value |

| Males | 5 (21.7) | 22 (44.9) | 0.071 |

| Age at diagnosis of uveitis (years) | 0.606 | ||

| Mean | 8.6 | 8.4 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 6.3 (4.8, 13.1) | 8.3 (6.2, 10.1) | |

| Min–max | 1.9–17.7 | 3.2–14.9 | |

| Age at diagnosis of arthritis (years) | 0.167 | ||

| Mean | 9.3 | 7.4 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 8.9 (5.9, 13.2) | 7.0 (3.5, 10.9) | |

| Min–max | 1.3-16.2 | 1.0–15.4 | |

| Anatomical type of uveitis | 0.385 | ||

| Anterior | 16 (69.6) | 26 (53.1) | |

| Pars planitis | 1 (4.3) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Posterior | 0 (0.0) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Panuveitis | 6 (26.1) | 13 (26.5) | |

| Manifested (“red-eye”) uveitis | 15 (65.2) | 13 (26.5) | 0.004 |

| Unilateral uveitis | 17 (73.9) | 17 (34.7) | 0.002 |

| Eye complications at first examination | 7 (30.4) | 14 (28.6) | 1.0 |

| Antinuclear antibodies positivity | 7/20 (35.0) | 21/47 (44.7) | 0.591 |

| Uveitis appearance | 0.795 | ||

| Before arthritis | 6 (26.1) | 10 (20.4) | |

| Simultaneously with arthritis | 4 (17.4) | 5 (10.2) | |

| After arthritis | 8 (34.8) | 17 (34.7) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Chronic idiopathic uveitis | 5 (21.7) | 16 (32.7) | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.893 | ||

| Mean | 7.4 | 22.2 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.0 (1.0, 8.9) | 1.0 (0.6, 11.9) | |

| Min–max | 1.0–30.0 | 0.0–133.0 | |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 0.132 | ||

| Mean | 28.9 | 21.6 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 24.0 (20.0, 39.0) | 15.0 (8.0, 25.0) | |

| Min–max | 8.0-56.0 | 2.0–77.0 | |

| Active joint at onset | 0.344 | ||

| Mean | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1 (1.0, 3.0) | |

| Min–max | 1.0–3.0 | 1.0–5.0 |

HLA-B27-positive individuals over the age of seven exhibited a significantly greater likelihood of developing acute symptomatic uveitis when compared with those who were under the age of seven (OR = 12.3, 95%CI: 1.11-688.92, P = 0.03).

Two regression models were developed to identify predictors of manifested (“red eye”) uveitis using the following variables: (1) Age at onset of uveitis; and (2) HLA-B27 status. In the first model, age at onset was treated as a continuous variable, while in the second model, it was categorical with patients divided into two groups based on their age at onset: (1) Those younger than 7 years; and (2) Those 7 years or older.

A mixed regression model incorporating quantitative and qualitative variables identified the age of disease onset (β = 0.233, OR = 1.3, 95%CI: 0.07-0.42, P = 0.008) and HLA-B27 status (β = 1.920, OR = 6.8, 95%CI: 0.75-3.24, P = 0.002) as significant predictors of manifest (“red eye”) uveitis. With each additional year of age at onset, the log OR increased by 0.233.

The regression model with categorical predictors showed similar results. The age of onset over 7 years (β = 1.810, OR = 6.1, 95%CI: 0.60-3.40, P = 0.010), and the presence of HLA-B27 (β = 2.310, OR = 10.1, 95%CI: 1.10-3.90, P = 0.001) were significant predictors of manifested (“red eye”) uveitis.

In the cohort of patients with uveitis, unilateral involvement was significantly associated with a more severe (or “red eye”) course of uveitis (OR = 2.1, 95%CI: 1.00-4.30, P = 0.042) as well as with the presence of HLA-B27 (OR = 5.2, 95%CI: 1.60-19.30, P = 0.002). There was also a tendency towards a higher ESR in this group (P = 0.086) as well as a slight predominance of anterior uveitis (P = 0.082) as shown in Table 4.

| Parameter | Unilateral (n = 67) | Bilateral (n = 82) | P value |

| Females | 34 (50.7) | 49 (59.8) | 0.321 |

| Age at diagnosis of uveitis (years) | 0.880 | ||

| Mean | 7.1 | 7.2 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 6.1 (4.4, 8.4) | 6.5 (4.2, 9.8) | |

| Min–max | 2.3-17.7 | 1.5–16.8 | |

| Age at diagnosis of arthritis (years) | 0.710 | ||

| Mean | 6.4 | 6.5 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 5.7 (3.8, 8.3) | 5.4 (2.4, 10.4) | |

| Min–max | 1.2–14.2 | 1.0–16.2 | |

| Anatomical type of uveitis | 0.082 | ||

| Anterior | 52 (77.6) | 48 (58.5) | |

| Pars planitis | 1 (1.5) | 5 (6.1) | |

| Posterior | 3 (4.5) | 5 (6.1) | |

| Panuveitis | 11 (16.4) | 24 (29.3) | |

| Manifested (“red-eye”) uveitis | 32 (47.8) | 25/62 (40.3) | 0.042 |

| Human leukocyte antigen-B27 (+) | 17/34 (50.0) | 6/38 (15.8) | 0.002 |

| Eye complications at first examination | 17 (25.4) | 29 (35.4) | 0.215 |

| Antinuclear antibodies positivity | 33/64 (51.6) | 47/75 (62.7) | 0.229 |

| Uveitis appearance | 0.115 | ||

| Before arthritis | 18 (26.9) | 13 (15.9) | |

| Simultaneously with arthritis | 9 (13.4) | 10 (12.2) | |

| After arthritis | 21 (31.3) | 38 (46.3) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Chronic idiopathic uveitis | 18 (26.9) | 21 (25.6) | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.194 | ||

| Mean | 23.8 | 19.3 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 3.7 (1.0, 23.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 15.2) | |

| Min–max | 0.1–192.0 | 0.0–133.0 | |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 0.086 | ||

| Mean | 30.5 | 22.7 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 24.0 (11.0, 49.0) | 17.0 (7.0, 26.0) | |

| Min–max | 4.0–78.0 | 2.0–77.0 | |

| Active joint at onset | 0.698 | ||

| Mean | 1.9 | 1.8 | |

| Median (25%, 75%) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | |

| Min–max | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–7.0 |

Our study confirmed the idea that there was a close relationship between CIU and JIA. We found a number of similarities between the two conditions including delayed initiation of systemic immunosuppressive treatment in patients with CIU.

Over the past 15 years, uveitis epidemiology has been studied extensively in various populations. This has allowed us to determine the epidemiological characteristics of uveitis associated with JIA and idiopathic uveitis. Childhood uveitis accounts for approximately 5%-10% of all uveitis cases in the population[4]. Childhood uveitis is more common in females than in males, similar to other immunoinflammatory conditions. These findings are generally consistent with our study, although the difference between females and males in our sample was small (55.3% females, 44.7% males). Table 5 presents data from previous studies on the subject[6-9,15,16].

| Parameter | Our study, 2024 | Siiskonen et al[6], 2021 | Sun et al[7], 2022 | Shin et al[8], 2021 | Kim et al[9], 2022 | BenEzra et al[15], 2005 | Päivönsalo-Hietanen et al[16], 2000 |

| Sample size | 150 | 150 | 209 | 155 | 5972 | 276 | 55 |

| Females | 84 (56.0) | 79 (53.0) | 106 (50.7) | 74 (47.7) | 2442 (41.0) | 139 (50.4) | 34 (62.0) |

| Mean age at onset (years) | 7.2 (4.4-9.1) | 6.9 ± 3.9 | 9.0 (7.0-12.0) | 13.0 (9.5-16.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis | 110 (73.3) | 95 (61.0) | 17 (8.1) | 23 (14.8) | 926 (8.7) | 41 (14.9) | 20 (36.3) |

| Females (with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis) | 67 (60.9) | 60 (76.0) | NA | 8 (34.8) | NA | NA | 15 (75.0) |

Some researchers propose that U-JIA and CIU, particularly anterior uveitis, may be the same condition[17]. Clinically, CIU cannot be distinguished from U-JIA based on ocular characteristics[18,19]. Our study did not reveal significant differences in the initial demographic and immunological characteristics of patients, consistent with the current understanding of the pathogenesis of autoimmune uveitis in childhood. However, there were notable variations in the levels of CRP at the onset, potentially reflecting joint inflammation. Furthermore, the anatomical type of uveitis among patients with long-term autoimmune uveitis without arthritis was more diverse.

In contrast to U-JIA, routine ophthalmological screening for uveitis is not performed in patients with CIU, leading to more vision-threatening ocular complications due to delayed detection. However, Russian clinical guidelines for non-infectious uveitis define a procedure for monitoring this patient group[17].

Analysis of cohorts stratified by HLA-B27 status revealed interesting findings. Traditionally, risk factors for acute uveitis with symptoms in JIA children were believed to include male gender and the presence of the HLA-B27 allele[13]. Our study identified associations between the presence of HLA-B27, uveitic manifestation type, and laterality. These associations showed an OR of 5.1 (95%CI: 1.60–17.50) for association with HLA-B27 and uveitis type, and an OR of 5.2 (95%CI: 1.60-19.30) for laterality association, with P values of 0.004 and 0.002, respectively.

These findings do not conflict with the current understanding of uveitis about the HLA-B27 within the context of JIA. The presence of this antigen in patients with JIA is linked to the development of enthesitis-related arthritis and increases the risk of acute anterior uveitis[20]. Remarkably in our study there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients who were positive for ANA and those who were HLA-B27-positive between the two groups, confirming the immunological similarities between these two conditions.

There have also been several studies conducted on adult acute anterior uveitis[21-23]. The regression analysis presented yielded interesting results, allowing us to conclude the influence of HLA-B27 and age of onset on the type of uveitis presentation. Both of these factors have proven significant in the development of acute symptomatic uveitis. Patients over 7 years of age who tested positive for HLA-B27 were more likely to develop classical acute symptomatic uveitis, while patients under 7 years exhibited an asymptomatic course more frequently. This suggests that HLA-B27 expression may vary depending on a patient’s age at diagnosis. Previous studies have documented similar age-related patterns where interactions between specific alleles are linked to protective effects in early life but increased risk in later childhood.

Our study also examined the effectiveness of treatment in both groups, revealing significant differences in the initiation of methotrexate therapy. The average time to start methotrexate treatment was significantly shorter for patients with U-JIA because the treatment of U-JIA is usually provided by pediatric rheumatologists and ophthalmologists. Pediatric rheumatology specialists are more knowledgeable about immune-suppressing medications and have guidelines for their use. However, patients with uveitis may be treated exclusively by ophthalmologists who are not as familiar with these drugs[18].

In our tertiary clinics, there is close cooperation between pediatric rheumatology and ophthalmology specialists. Patients with uveitis resistant to topical treatment are referred to pediatric rheumatology for further evaluation. If necessary, they may be prescribed conventional or biological DMARDs to manage their condition.

Conventional anti-rheumatic treatment is equally effective in controlling the inflammatory process, allowing for successful management. In particular, patients with chronic, idiopathic uveitis experienced a significantly higher risk of flare-ups during methotrexate therapy compared to those with U-JIA, although the time until the first recurrence is similar in both groups. Based on our findings, we suggest that delayed initiation of immune-suppressive treatment in patients with chronic uveitis may result in inferior outcomes.

When immunomodulatory therapies are used appropriately, long-term visual outcomes for the two groups are similar[24]. Specifically, patients with ANA-positive CIU share similarities with those with U-JIA regarding clinical history, response to systemic therapy, and characteristics of uveitis[25]. The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and new therapeutic guidelines recommend similar treatment approaches for U-JIA and chronic anterior uveitis[10,26-28].

The study had several limitations. First, the data collection was retrospective, which may have introduced biases. Second, there were missing data points, which could have affected the accuracy of the results. Third, there was no standardized diagnostic or treatment protocol, which made it difficult to compare results across different patients.

Additionally, the study population was heterogeneous as patients had different disease durations and different times before admission to the clinic. This could have influenced the outcomes of the study. Furthermore, the quality of medical records was an issue, leading to insufficient data and potentially inaccurate results.

This study confirmed the similarities between CIU and U-JIA. These two conditions share many similarities, and delayed systemic immunosuppressive therapy is typical for patients with CIU. Treatment for CIU is generally more conservative with delayed initiation of systemic therapy, which may affect long-term outcomes. The introduction of methotrexate in chronic uveitis cases can lead to rapid control of the disease.

It is essential to develop improved protocols for the diagnosis and treatment of both U-JIA and CIU. Collaboration between rheumatologists and ophthalmologists will be crucial in managing both types of uveitis effectively.

| 1. | Wu X, Tao M, Zhu L, Zhang T, Zhang M. Pathogenesis and current therapies for non-infectious uveitis. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23:1089-1106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghadiri N. The history of uveitis: from antiquity to the present day. Eye (Lond). 2025;39:488-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT; Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2474] [Cited by in RCA: 3221] [Article Influence: 161.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Edelsten C, Lee V, Bentley CR, Kanski JJ, Graham EM. An evaluation of baseline risk factors predicting severity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis and other chronic anterior uveitis in early childhood. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta A, Ramanan AV. Uveitis in Children: Diagnosis and Management. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Siiskonen M, Hirn I, Pesälä R, Hautala T, Ohtonen P, Hautala N. Prevalence, incidence and epidemiology of childhood uveitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99:e160-e163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sun N, Wang C, Linghu W, Li X, Zhang X. Demographic and clinical features of pediatric uveitis and scleritis at a tertiary referral center in China. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22:174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shin Y, Kang JM, Lee J, Lee CS, Lee SC, Ahn JG. Epidemiology of pediatric uveitis and associated systemic diseases. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim BH, Chang IB, Lee S, Oh BL, Hong IH. Incidence and Prevalence of Pediatric Noninfectious Uveitis in Korea: A Population-Based Study. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Angeles-Han ST, Lo MS, Henderson LA, Lerman MA, Abramson L, Cooper AM, Parsa MF, Zemel LS, Ronis T, Beukelman T, Cox E, Sen HN, Holland GN, Brunner HI, Lasky A, Rabinovich CE; Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Disease-Specific and Uveitis Subcommittee of the Childhood Arthritis Rheumatology and Research Alliance. Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Consensus Treatment Plans for Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated and Idiopathic Chronic Anterior Uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71:482-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Skarin A, Elborgh R, Edlund E, Bengtsson-Stigmar E. Long-term follow-up of patients with uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cohort study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:104-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kotaniemi K, Arkela-Kautiainen M, Haapasaari J, Leirisalo-Repo M. Uveitis in young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a clinical evaluation of 123 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:871-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sen ES, Ramanan AV. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis. Clin Immunol. 2020;211:108322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, He X, Maldonado-Cocco J, Orozco-Alcala J, Prieur AM, Suarez-Almazor ME, Woo P; International League of Associations for Rheumatology. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390-392. [PubMed] |

| 15. | BenEzra D, Cohen E, Maftzir G. Uveitis in children and adolescents. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:444-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Päivönsalo-Hietanen T, Tuominen J, Saari KM. Uveitis in children: population-based study in Finland. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:84-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van Meerwijk C, Kuiper J, van Straalen J, Ayuso VK, Wennink R, Haasnoot AM, Kouwenberg C, de Boer J. Uveitis Associated with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31:1906-1914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Holland GN, Denove CS, Yu F. Chronic anterior uveitis in children: clinical characteristics and complications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:667-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ferrara M, Eggenschwiler L, Stephenson A, Montieth A, Nakhoul N, Araùjo-Miranda R, Foster CS. The Challenge of Pediatric Uveitis: Tertiary Referral Center Experience in the United States. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27:410-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Du L, Kijlstra A, Yang P. Immune response genes in uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:249-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Werkl P, Rademacher J, Pleyer U. [HLA-B27 positive anterior uveitis : Clinical aspects, diagnostics, interdisciplinary management and treatment]. Ophthalmologie. 2023;120:108-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Or C, Lajevardi S, Ghoraba H, Park JH, Onghanseng N, Halim MS, Hasanreisoglu M, Hassan M, Uludag G, Akhavanrezayat A, Nguyen QD. Posterior Segment Ocular Findings in HLA-B27 Positive Patients with Uveitis: A Retrospective Analysis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:1271-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Leino A, Pesälä R, Siiskonen M, Ohtonen P, Hautala N. Clinical Characteristics of HLA-B27-Associated Anterior Uveitis in a Finnish Population-Based Cohort. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2025;33:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kouwenberg CV, Wennink RAW, Shahabi M, Bozkir I, Ayuso VK, de Boer JH. Clinical Course and Outcome in Pediatric Idiopathic Chronic Anterior Uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;241:198-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Heiligenhaus A, Klotsche J, Niewerth M, Horneff G, Ganser G, Haas JP, Minden K. Similarities in clinical course and outcome between juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)-associated and ANA-positive idiopathic anterior uveitis: data from a population-based nationwide study in Germany. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Heiligenhaus A, Minden K, Tappeiner C, Baus H, Bertram B, Deuter C, Foeldvari I, Föll D, Frosch M, Ganser G, Gaubitz M, Günther A, Heinz C, Horneff G, Huemer C, Kopp I, Lommatzsch C, Lutz T, Michels H, Neß T, Neudorf U, Pleyer U, Schneider M, Schulze-Koops H, Thurau S, Zierhut M, Lehmann HW. Update of the evidence based, interdisciplinary guideline for anti-inflammatory treatment of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49:43-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Foeldvari I, Maccora I, Petrushkin H, Rahman N, Anton J, de Boer J, Calzada-Hernández J, Carreras E, Diaz J, Edelsten C, Angeles-Han ST, Heiligenhaus A, Miserocchi E, Nielsen S, Saurenmann RK, Stuebiger N, Baquet-Walscheid K, Furst D, Simonini G. New and Updated Recommendations for the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis and Idiopathic Chronic Anterior Uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2023;75:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Solebo AL, Rahi JS, Dick AD, Ramanan AV, Ashworth J, Edelsten C; Members of the POIG Uveitis Delphi Group. Areas of agreement in the management of childhood non-infectious chronic anterior uveitis in the UK. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |